Ahwatukee, Phoenix

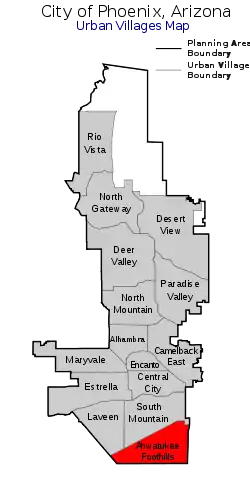

Ahwatukee Foothills (also Ahwatukee) is an urban village of Phoenix, Arizona. Ahwatukee forms the southernmost portion of Phoenix, and is considered part of the East Valley region of the Phoenix metropolitan area.[4]

Ahwatukee | |

|---|---|

| Ahwatukee Foothills Village[1] | |

A typical Ahwatukee neighborhood as seen from South Mountain Park | |

| Motto(s): Warm People, Bright Future[1] | |

Location of Ahwatukee Foothills highlighted in red. | |

Ahwatukee Location of Ahwatukee Foothills highlighted in red.  Ahwatukee Ahwatukee (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 33°20′30″N 111°59′3″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | Maricopa |

| City | Phoenix |

| Area | |

| • Total | 35.8 sq mi (93 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,283 ft (391 m) |

| Population (2016 Estimate)[2] | |

| • Total | 83,464 |

| • Density | 1,783/sq mi (688/km2) |

| GNIS feature ID | 24705[3] |

| Website | Ahwatukee Foothills Village Planning Committee |

History

Prior to the area's development into the community it is known today, the name "Ahwatukee" referred, at times, to a since-demolished house that sat in an area near Sequoia Trails and Appaloosa Drive, west of the Warner-Elliot Loop.[5]

Beginnings

At least two major thoroughfares in today's Ahwatukee are named after people who claimed lands in the area, in the decades following the signing of the Homestead Act in 1862.[6] Warner Road was named after Samuel Warner of Kansas, while Elliot Road was named after Reginald Elliott of California.[6] Both claimed lands in an area now known as Tempe.[6] A third man, Arthur Hunter, claimed land within an area now known as Ahwatukee. The street known today as 48th Street was, for a time, named Hunter Drive, after Arthur Hunter.[6] Hunter is rumored to have, in the 1940s, disassembled and buried in the Ahwatukee desert a Studebaker auto purportedly owned by Al Capone.[6]

Ahwatukee ranch

One of the first houses in the area was built by Dr. William Van Bergen Ames, who co-founded Northwestern University's now-closed Dental School.[7] The house was built on a piece of land measuring over 2,000 acres (810 ha),[8] which was purchased for $4 an acre.[6]

At the time, the Chandler Arizonan newspaper called the house, built in the foothills of the South Mountain, "unmatched in scope and size".[7] The house was noted to be a 12,000 square feet (1,100 m2) winter residence, designed by prominent Phoenix architect Lester Mahoney, with construction starting in 1921.[7]

The house was given the name "The Mystic House" by the Chandler Arizonan, due to its cost, size, and isolated location.[7] The Ames, however, called it Casa de Sueños.[8][7] They moved into the house on Thanksgiving of 1921,[7] but Dr. Ames died suddenly in February 1922.[7][9] Ames' wife continued to spend her winters at the house until her death in 1933.[7]

Following Ames' wife's death, the Ames' property in Ahwatukee was willed to St. Luke's Hospital.[9] The property was bought by Helen Brinton in 1935,[8][9] who gave the house (and eventually the area) the name it is known by today (as explained below). Brinton died in 1960,[6] and the house was demolished in 1979.[10]

Proving grounds

In 1946, the International Harvester Company rented land from a United States Army tank testing facility located west of today's Lakewood community, for use as truck and heavy equipment proving grounds.[6] The proving grounds eventually grew to over 4,000 acres (1,600 ha).[6]

The grounds were designed to stress-test trucks and heavy equipment with, among other things, a 7.5 miles (12.1 km) test track, dirt tracks, a special testing area with 20 to 60% grade, service shops, and a runway for company executives.[11] The grounds were sold to a property development company in 1983, due to a combination of economic issues, labor union problems, and a patent infringement judgement against the company.[11] The area is now a part of The Foothills and Club West developments.[11]

Development

Development of Ahwatukee began in 1970, when Presley Development Company, led by Randall Presley, bought 2,080 acres (840 ha) of land.[10] The land included Ahwatukee Ranch, then owned by a land syndicate led by an Arizona State University English professor, as well as land owned by a local moving and storage firm.[12] Presley originally planned for the area to be a retirement community, but later devised a mix of retirement living, family living, and light commercial zoning for the area.[12]

Presley Development was noted to have a role in Ahwatukee eventually becoming a part of Phoenix, instead of neighboring Chandler or Tempe, through a handshake deal between Maricopa County Supervisor Bob Stark, who was also an attorney with Presley Development, and Mayor of Phoenix John D. Driggs.[13] However, Chandler and Tempe officials were noted to have refused offers of annexing Ahwatukee.[10][13]

Phoenix annexed the area in stages, from 1980 to 1987.[10] It has been suggested that Phoenix's annexation of Ahwatukee had, to a degree, affected Tempe's future development.[14]

Plans for Ahwatukee were approved by Maricopa County in November 1971, and 17 model homes were opened in an area near 50th Street and Elliot Road in 1973.[10][15]

In the same year as the model homes’ opening, the Arizona State Legislature set aside $5 million to build a prison near the proving grounds. Plans for the prison, however, were later scrapped.[10][11]

The area's first elementary school, Kyrene de los Lomas, opened in 1976, while Mountain Pointe High School opened as the area's first high school in 1991.[10]

Etymology

There exist three theories surrounding the name "Ahwatukee", with all three claiming the name has roots in the Crow language.

Some stories of the name's origin trace back to Brinton, who chose a Crow-rooted name for her new property due to her time among the Crow Nation tribal members in Wyoming, and the influence it subsequently had on her.[9]

House of dreams

Some sources claim the name is a Crow term for house of your dreams,[8] house of my dreams,[16] or house of dreams[9][7]

Until at least 2006, the Ahwatukee Foothills Chamber of Commerce acknowledged house of dreams as the meaning of the area's name.[17]

However, according to the Crow language dictionary maintained by the Crow Language Consortium,[18] the Crow word for "house" is ashé,[19] and the Crow word for "dream" is baashíale[20] or balewaashíale.[21]

Land on the other side of the hill

Some sources claim the name is a Crow term for land on the other side of the hill,[9][22] based on the Crow word awe chuuke.[17] According to the same Crow dictionary, the word awé means "ground", "land", or "earth",[23] and the word chúuke means "over the ridge", "over the hill", or "the next valley over".[24]

Geography

The Ahwatukee Foothills Village is bordered by Interstate 10 to the east, South Mountain to the north, and the Gila River Indian Community to the west and south.[1] Ahwatukee is geographically isolated from the city of Phoenix, and was once seen as appropriate for semi-rural development.[15][27]

Demographics

Based on 2016 estimates, the Ahwatukee Foothills Village has 83,464 residents.[2] 83% of the population are White, 6.5% are Asian, 5.6% are Black or African American, 1.6% are Native American and 3.3% identify as some other race. 12.3% of the population is Hispanic.[2]

Due to the community's predominantly Caucasian racial makeup, the area has been called "All-White-tukee".[28][29]

Education

Public

K-8 public school students in the area attend schools operated by the Kyrene School District.[30] In fact, Ahwatukee-based schools constitute 12 out of 25 (48%) of Kyrene's schools.[31]

High school students go to one of two in the area: Desert Vista and Mountain Pointe. Both schools are operated by the Tempe Union High School District

Private

There are a number of private schools in Ahwatukee. One of the schools, Summit School of Ahwatukee, is ranked as one of the most expensive private schools in the Phoenix area by The Arizona Republic in 2014.[32]

Infrastructure

Transportation

The community is served by the ALEX neighborhood circulator, which is operated by Valley Metro Bus.[33] Riders, however, have complained of poor service after a new contractor took over the route in 2016.[34] Portions of Ahwatukee are also served by Valley Metro Routes 56-Priest Drive, 108-Elliot Road, 140-Ray Road, 156-Chandler Boulevard/Williams Field Road, and the I-10 East RAPID route.

As a result of having access points only via 48th Street in the northeastern part of the area, and a number of east–west crossings over I-10, Ahwatukee has been called the world's largest cul-de-sac.[15][27] The building of Loop 202's South Mountain Freeway segment, however, has given the area a western gateway, via a series of exits along the southern border of the community.[35]

Notable people

- Todd McFarlane - comic book creator, entrepreneur, writer and artist.

References

- "Ahwatukee Foothills Village" (PDF). City of Phoenix. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "Ahwatukee Foothills Village Primary Care Area (PCA) Statistical Profile 2016" (PDF). Arizona Department of Health Services. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Ahwatukee

- Reagor, Catherine; VanDenburgh, Barbara; Hansen, Ronald J. (15 April 2016). "Street Scout: Neighborhood guide to Tempe/Ahwatukee". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

The southern section of the city of Phoenix is known for its popular stucco homes with red-tile roofs. Circle roadways are the norm. The area is located next to South Mountain Park. Ahwatukee has good schools and an abundance of shopping. Considered part of the East Valley, the area draws many families and people who want to be closer in but still live a suburban life.

- Rodriguez, Nadine Arroyo (10 July 2015). "Did You Know: The Word 'Ahwatukee' Has No Meaning". KJZZ-FM. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Gibson, Marty (13 March 2012). "Our state has had some good years, leading to the development of Ahwatukee". Ahwatukee Foothills News. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Gibson, Marty W. (2006). "Four - The Ahwatukee Ranch". Phoenix's Ahwatukee-Foothills. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781439634301. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "Ahwatukee Board of Management - ABM History". Ahwatukee Board of Management. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Thompson, Clay (5 January 2015). "Lost in translation, Ahwatukee's name was born". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Gibson, Marty (16 March 2012). "Our state has had some good years, leading to the development of Ahwatukee, part two". Ahwatukee Foothills News. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Nothaft, Mark (12 April 2017). "What happened to the Phoenix Proving Ground near South Mountain?". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Gibson, Marty (27 April 2012). "Randall Presley: Ahwatukee visionary". East Valley Tribune. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Jensen, Edythe (4 March 2011). "Chandler, Tempe lost Ahwatukee to handshake". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Stern, Ray (18 June 2014). "Tempe Rising: The Landlocked College Town Explodes with New Development -- as Planned". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Gober, Patricia (2006). Metropolitan Phoenix: Place Making and Community Building in the Desert. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 161–162. ISBN 0812205820.

- "Ahwatukee". PHOENIX Magazine (April 2015). Retrieved 3 January 2018.

The word “Ahwatukee” means “house of my dreams” in the language of the Crow Nation.

- "Reflecting on what we call Ahwatukee". The Arizona Republic. 7 April 2006. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "Crow Language Consortium". Crow Language Consortium. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "ashé (í)". Crow Language Consortium. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "baashíale (i)". Crow Language Consortium. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "balewaashíale (i)". Crow Language Consortium. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Verstegen, Dominic (3 December 2015). "Top 5 names for Phoenix-area cities — and Ahwatukee didn't make the list". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

Ahwatukee got its name from the Native American Crow tribe phrase for “land on the other side of the hill.”

- "awé (á)". Crow Language Consortium. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "chúuke (a)". Crow Language Consortium. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Hill, Jane H. (15 September 2011). The Everyday Language of White Racism (2008 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781444356694. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "alawachúhke (a)". Crow Language Consortium. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Mankiewicz, Josh (24 August 2009). "In The Bedroom". Dateline NBC. NBC News. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

They call it the “world's largest cul-de-sac.” A place with nice homes, good schools, friendly neighbors. Ahwatukee is an affluent oasis south of Phoenix, but geographically isolated from the rest of the city.

- White, Kaila (2 May 2016). "N-word controversy at Phoenix high school altered their senior year, changed district's efforts to combat racism". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

For years, many who are familiar with the area have also called the neighborhood "All-White-tukee."

- Kovesdy, Joe; Murphy, Doug; Powers, Jim; Yara, Georgann (1 June 2005). "Desert Vista: 2 tales of same school". Ahwatukee Foothills News. Archived from the original on 2005-11-25. Retrieved 2018-10-05.

Having lived in Ahwatukee Foothills with his family for a decade, a community with a reputation of "allwhitetukee" by some...

- "About Kyrene". Kyrene School District. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

The District’s boundaries encompass all of Ahwatukee...

- "Kyrene Elementary School Annual Report School Year 2016-2017". Kyrene School District. p. 7. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Faller, Mary Beth (September 17, 2014). "15 most expensive Phoenix-area private schools". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- "Ahwatukee Circulator". Valley Metro. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Maryniak, Paul (24 August 2016). "Ahwatukee bus users complain of poor service under new operator". Ahwatukee Foothills News. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "South Mountain Freeway Map". Arizona Department of Transportation. Retrieved 3 January 2018.