Aldo Moro

Aldo Romeo Luigi Moro (Italian: [ˈaldo ˈmɔːro]; 23 September 1916 – 9 May 1978) was an Italian statesman and a prominent member of the Christian Democracy (DC). He served as 38th prime minister of Italy from December 1963 to June 1968 and then from November 1974 to July 1976.[1]

Aldo Moro | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

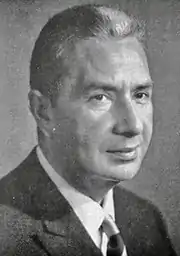

Moro in 1969 | |||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of Italy | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 23 November 1974 – 29 July 1976 | |||||||||||||||||

| President | Giovanni Leone | ||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Ugo La Malfa | ||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Mariano Rumor | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Giulio Andreotti | ||||||||||||||||

| In office 4 December 1963 – 24 June 1968 | |||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Pietro Nenni | ||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Giovanni Leone | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Giovanni Leone | ||||||||||||||||

| President of the Christian Democracy | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 October 1974 – 8 May 1976 | |||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Amintore Fanfani | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Flaminio Piccoli | ||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 7 July 1973 – 23 November 1974 | |||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Mariano Rumor | ||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Medici | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Mariano Rumor | ||||||||||||||||

| In office 5 May 1969 – 29 July 1972 | |||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Pietro Nenni | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Medici | ||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of the Christian Democracy | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 26 March 1959 – 27 January 1964 | |||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Amintore Fanfani | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Mariano Rumor | ||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Public Education | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 May 1957 – 15 February 1959 | |||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Paolo Rossi | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Medici | ||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Grace and Justice | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 6 July 1955 – 15 May 1957 | |||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Antonio Segni | ||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Michele De Pietro | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Guido Gonella | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||

| Born | Aldo Romeo Luigi Moro 23 September 1916 Maglie, Apulia, Kingdom of Italy | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 9 May 1978 (aged 61) Rome, Lazio, Italy | ||||||||||||||||

| Cause of death | Assassination | ||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Christian Democracy | ||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Eleonora Chiavarelli

(m. 1945–1978) | ||||||||||||||||

| Children | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Bari | ||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Professor | ||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||

Moro also served as Minister of Foreign Affairs from May 1969 to July 1972 and again from July 1973 to November 1974; during his ministry he implemented a pro-Arab policy, which characterised Italy during the 1970s and the 1980s. Moreover, he was appointed Minister of Justice and of Public Education during the 1950s. From March 1959 until January 1964, Moro served as secretary of the Christian Democracy.[2] On 16 March 1978 he was kidnapped by the far-left terrorist group Red Brigades and killed after 55 days of captivity.[3]

He was one of Italy's longest-serving post-war Prime Ministers, leading the country for more than six years. An intellectual and a patient mediator, especially in the internal life of his own party, during his rule, Moro implemented a series of social and economic reforms which deeply modernized the country.[4] Due to his accommodation with the Communist leader Enrico Berlinguer, known as the Historic Compromise, Moro is widely considered one of the most prominent fathers of the modern Italian centre-left and one of the greatest and most popular leaders in the history of the Italian Republic.[5]

Early life

Aldo Moro was born in 1916 in Maglie, near Lecce, in the Apulia region, into a family from Ugento. His father, Renato Moro, was a school inspector, while his mother, Fida Sticchi, was a teacher. At the age of 4, he moved with his family to Milan, but they soon moved back to Apulia, where he gained a classical high school degree at Archita lyceum in Taranto.[6] In 1934, his family moved to Bari, where he studied law at the local University, graduating in 1939. After the graduation, he became a professor of philosophy of law and colonial policy (1941) and of criminal law (1942), at the University of Bari.[7]

In 1935, he joined the Italian Catholic Federation of University Students (FUCI) of Bari. In 1939, under approval of Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Pope Paul VI, whom he had befriended, Moro was chosen as president of the association; he kept the post until 1942 when he was forced to fight in the World War II and was succeeded by Giulio Andreotti, who at the time was a law student from Rome.[8] During his university years, Italy was ruled by the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini, and Moro took part in students competitions known as Lictors of Culture and Art organised by local fascist students' organisation, the University Fascist Groups.[9] In 1943, along with other Catholic students, he founded the periodical La Rassegna, which was published until 1945.[10]

In July 1943, Moro contributed, along with Mario Ferrari Aggradi, Paolo Emilio Taviani, Guido Gonella, Giuseppe Capograssi, Ferruccio Pergolesi, Vittore Branca, Giorgio La Pira, Giuseppe Medici and Andreotti, to the creation of the Code of Camaldoli, a document planning of economic policy drawn up by members of the Italian Catholic forces.[11] The Code served as inspiration and guideline for economic policy of the future Christian democrats.[12][13]

In 1945, he married Eleonora Chiavarelli (1915–2010), with whom he had four children: Maria Fida (born 1946), Agnese (1952), Anna, and Giovanni (1958).[14] In 1963 Moro was transferred to La Sapienza University of Rome, as a professor of the institutions of law and criminal procedure.

Early political career

Aldo Moro developed his interest in politics between 1943 and 1945. Initially, he seemed to be very interested in the social-democratic component of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), but then he started cooperating with other Christian democratic politician in opposition to the fascist regime. During these years he met Alcide De Gasperi, Mario Scelba, Giovanni Gronchi and Amintore Fanfani. On 19 March 1943 the group reunited in the house of Giuseppe Spataro officially formed the Christian Democracy (DC).[15] In the DC, he joined the left-wing faction led by Giuseppe Dossetti, of whom he became a close ally.[16] In 1945 he became director of the magazine Studium and president of the Graduated Movement of the Catholic Action (AC), a widespread Roman Catholic lay association.[17]

In 1946, he was appointed vice-president of the Christian Democracy and elected member of the Constitutional Assembly, where he took part in the work to redact the Italian Constitution.[18] Moro run for the constituency of Bari–Foggia, where he received nearly 28,000 votes.[19]

In 1948, he was elected with 63,000 votes to the newly formed Chamber of Deputies[20] and appointed Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs in the De Gasperi V Cabinet, from 23 May 1948 to 27 January 1950.[21]

After Dossetti's retirement in 1952, Moro founded, along with Antonio Segni, Emilio Colombo and Mariano Rumor, the Democratic Initiative faction, led by his old friend Fanfani.[22]

In government

In 1953, Moro was re-elected to the Chamber of Deputies, where he held the position of chairman of the DC parliamentary group.[23] In 1955, was appointed as Minister of Grace and Justice in the cabinet led by Antonio Segni.[24] In the following year he resulted among the most voted during the party's congress.

In May 1957, the Italian Socialist Democratic Party (PSDI) withdrew its support to the government and on 6 May, Segni resigned.[25] On 20 May, Adone Zoli sworn in as new head of government and Moro was appointed Minister of Education[26] However, after the 1958 general election, Zoli resigned and, on 1 July 1958, Fanfani sworn in as new Prime Minister at the head of a coalition government with the PSDI, and a case-by-case support by the Italian Republican Party (PRI).[27] Moro was confirmed at the head of Italian education and remained in office until February 1959. During his tenure, he introduced the study of civic education in schools.[28][29][30]

In March 1959, after Fanfani's resignation as Prime Minister, a new congress was called. The leaders of the Democratic Initiative faction reunited themselves in the convent of Dorothea of Caesarea, where they abandoned the leftist policies promoted by Fanfani and founded the Dorotei (Dorotheans) faction.[31] In the party's national council, Moro was elected Secretary of DC and was then confirmed in the October's congress held in Florence.[32]

After the brief right-wing government led by Fernando Tambroni in 1960, supported by the decisive votes of the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement (MSI), the renovated alliance between Moro as secretary and Fanfani as Prime Minister, led the subsequent National Congress, held in Naples in 1962 to approve with a large majority a line of collaboration with the Italian Socialist Party (PSI).[33]

The 1963 general election was characterized by a lack of consensus for the DC;[34] in fact, the election was held after the launch of the centre-left formula by the Christian Democracy, a coalition based upon the alliance with the Socialists, which had left their alignment with the Soviet Union. Some rightist electors abandoned the DC for the Italian Liberal Party (PLI), which was asking for a centre-right government and received votes also from the quarrelsome monarchist area. Moro refused the office of Prime Minister, preferring to provisionally maintain his more influential post at the head of the party. However the Christian Democrats decided to replace incumbent premier, Fanfani, with a provisional administration led by impartial Presidento of the Chamber, Giovanni Leone;[35] but, when the congress of the PSI in autumn authorized a full engagement of the party into the government, Leone resigned and Moro became the new Prime Minister.[36]

First term as Prime Minister

Aldo Moro's government was unevenly supported by the DC, but also by the Italian Socialist Party, along with the minor Italian Republican Party and Italian Democratic Socialist Party. The coalition was also known as Organic Centre-left and was characterized by consociationalist and social corporatist tendencies.[37]

Social reforms

During Moro's premiership, a wide range of social reforms were carried out. The 1967 Bridge Law (Legge Ponte) introduced urgent housing provisions as part of an envisioned reform of the entire sector, such as the introduction of minimum standards for housing and environment.[38] A reform, promulgated on 14 December 1963, introduced an annual allowance for university students with income below a given level. Another law, promulgated on 10 March 1968, introduced voluntary public pre-elementary education for children aged three to five years. While a bill, approved on 21 July 1965, extended the program of social security.[39]

Moreover, the legal minimum wage was raised, all current pensions were revalued, seniority pensions were introduced (after 35 years of contributions workers could retire even before attaining pensionable age), and within the Social Security National Institute (INPS), a Social Fund (Fondo Sociale) was established, ensuring to all members pensioners a basic uniform pension largely financed by state, known as the "social pension".[40] A law, approved on 22 July 1966, extended social security insurance to small traders, while law of 22 July 1966 extended health insurance to retired traders. Another important reform was implemented with a bill, approved on 29 May 1967, which extended compulsory health insurance to retired farmers, tenant farmers, and sharecroppers, and extended health insurance to the unemployed in receipt of unemployment benefits.[41] Moreover, a law of 5 November 1968 extended family allowances to the unemployed who received unemployment benefits.[42]

Vajont Dam disaster

During his premiership, Moro had to face the outcome of one of the most tragic events in Italian republican history, the Vajont Dam disaster.[43] On 9 October 1963, a few weeks before his oath as Prime Minister, a landslide occurred on Monte Toc, in the province of Pordenone. The landslide caused a megatsunami in the artificial lake in which 50 million cubic metres of water overtopped the dam in a wave of 250 metres (820 ft), leading to the complete destruction of several villages and towns, and 1,917 deaths.[44]

In the previous months, the Adriatic Society of Electricity (SADE) and the Italian government, which both owned the dam, dismissed evidence and concealed reports describing the geological instability of Monte Toc on the southern side of the basin and other early warning signs reported prior to the disaster.[45]

Immediately after the disaster, government and local authorities insisted on attributing the tragedy to an unexpected and unavoidable natural event. However, numerous warnings, signs of danger, and negative appraisals had been disregarded in the previous months and the eventual attempt to safely control the landslide into the lake by lowering its level came when the landslide was almost imminent and was too late to prevent it.[46] The communist newspaper L'Unità was the first to denounce the actions of management and government.[47] The DC accused the PCI of political profiteering from the tragedy, promising to bring justice to the people killed in the disaster.[48]

Differently from his predecessor, Giovanni Leone, who even became the head of SADE's team of lawyers, Moro acted strongly to condemn the managers of the society, immediately dismissing the administrative officials who had supervised the construction of the dam.[49]

Coalition crisis and presidential election

On 25 June 1964, the government was beaten on the budget law for the Italian Ministry of Education concerning the financing of private education, and on the same day Moro resigned. The moderate Christian Democratic President of Italy, Antonio Segni, during the presidential consultations for the formation of a new cabinet, asked the socialist leader Pietro Nenni to exit from the government majority.[50]

On 16 July, Segni sent the Carabinieri general, Giovanni De Lorenzo, to a meeting of representatives of DC, to deliver a message in case the negotiations around the formation of a new centre-left government would fail. According to some historians, De Lorenzo reported that President Segni was ready to give a subsequent mandate to the President of the Senate Cesare Merzagora, asking him of forming a "president's government", composed by all the conservative forces in the Parliament.[51][52] Moro, on the other hand, managed to form another centre-left majority. During the negotiations, Nenni had accepted the downsizing of his reform programs and, on 17 July, Moro went to the Quirinal Palace, with the acceptance of the assignment and the list of ministers of his second government.[53]

In August 1964, President Segni suffered a serious cerebral hemorrhage and resigned after a few months.[54] In December presidential election, Moro and his majority tried to elect a leftist politician at the Quirinal Palace. On the twenty-first round of voting, the leader of the PSDI and former President of the Constituent Assembly Giuseppe Saragat was elected President with 646 votes out of 963. Saragat was the first left-wing politician to become President of the Republic.[55][56]

Resignation

Despite the opposition by Segni and other prominent rightist Christian Democrats, the centre-left coalition, the first one for the Italian post-war political life, stayed in power for nearly five years, until the 1968 general election, which was characterised by a defeat for DC's centre-left allies.[57] The socialists and the social democrats run in a joint list named Unified Socialist Party (PSU), which however lost many votes compared to the previous election, while the communists gained ground, achieving 30% of votes in the Senate.[58] The PSI and PSDI decided to exit from the government and Saragat appointed Giovanni Leone at the head of the a new cabinet, composed only by Christian Democracy's members.[59]

Minister of Foreign Affairs

In the 1968 DC's congress, Moro yielded the Secretariat and passed to internal opposition. On 5 August 1969, he was appointed Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs by Prime Minister Mariano Rumor,[60] a position that he also held under the premierships of Emilio Colombo and Giulio Andreotti.[61]

Pro-Arab policies

During his ministry, Moro continued the pro-Arab policy of his predecessor Fanfani.[62] He forced Yasser Arafat to promise not to carry out terrorist attacks in Italian territory, with a commitment that was named "Moro pact".[63][64]

The existence of this pact and its validity was confirmed by Bassam Abu Sharif, a long-time leader of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Interviewed by the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, he confirmed the existence of an agreement between Italy and the Popular Front thanks to which, the PFLP could "transport weapons and explosives, guaranteeing immunity from attacks in return".[65] Abu Sharif also declared:" I personally followed the negotiations for the agreement. Aldo Moro was a great man, a true patriot, who wanted to save Italy some headaches, but I never met him. We discussed the details with an admiral and agents of the Italian secret service. The agreement was defined and since then we have always respected it; we were allowed to organize small transits, passages, purely Palestinian operations, without involving Italians. After the deal, every time I came to Rome, two cars were waiting for me to protect myself. For our part, we also guaranteed to avoid embarrassment to your country, that is attacks which started directly from the Italian soil."[66][67] This version was confirmed also by former President of Italy Francesco Cossiga, who stated that Moro was the real and only creator of the pact.[68]

Moro also had to cope with the difficult situation which erupted following the coup of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya,[69] a very important country for Italian interests not only for colonial ties, but also for its energy resources and the presence of about 20,000 Italians.[70]

1971 presidential election

.jpg.webp)

In 1971, Amintore Fanfani was proposed as Christian Democracy's candidate for the Presidency of the Republic. However his candidacy was weakened by the divisions within his own party and the candidacy of the socialist Francesco De Martino, who received votes from PCI, PSI and some PSDI members.[71]

Fanfani retired after several unsuccessful ballots and Moro was then proposed as candidate by the left-wing faction; however the right-wing strongly opposed him and the moderate conservative Christian Democrats Giovanni Leone was slightly preferred to him.[72] At the twenty third round Leone was finally elected with a centre-right majority, with 518 votes out of 996, including those of the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement (MSI).[73]

Italicus Express bombing

On 4 August 1974, a bomb exploded on the Italicus Express, killing 12 people and injuring 48. The train was travelling from Rome to Munich; having left Florence about 45 minutes earlier, it was approaching the end of the long San Benedetto Val di Sambro tunnel under the Apennines. The bomb had been placed in the fifth passenger car of the train and exploded at 01:23, while the train was reaching the end of the tunnel.[74] The effects of the explosion and subsequent fire would have been even more terrible if the train would remain inside the tunnel.[75]

According to what was Moro's daughter, Maria Fida, stated in 2004, Moro should have been on board, but a few minutes before departure he was joined by some officials of the Ministry who made him get off to sign some important documents.[76] According to some reconstructions, Aldo Moro would have been the real target of the attack.[77]

Second term as Prime Minister

In October 1974, Rumor resigned as Prime Minister after failing to come to an agreement on how to deal with rising economic inflation.[78][79] In November, President Leone gave Moro the task of forming a new cabinet; he was sworn in on 23 November, at the head a cabinet composed by DC and PRI, externally supported by PSI and PSDI.[80]

Even during his second term as Prime Minister, the government implemented a series of important social reforms.[81] A law, approved on 9 June 1975, increased the number of occupational diseases and extended the duration of linked insurance and benefit; while a bill, approved on 3 June 1975, introduced various improvements for pensioners. Moreover, the multiplying coefficient was raised to 2% and it was applied to average earnings of the best 3 years in the last 10 years of work and automatic annual adjustment of minimum pensions. A law of 27 December 1975 implemented ad hoc upgradings of cash benefits for certain diseases.[42]

Osimo Treaty

During his premiership, Moro signed the Osimo Treaty with Yugoslavia, defining the official partition of the Free Territory of Trieste. The port city of Trieste with a narrow coastal strip to the north west (Zone A) was given to Italy; a portion of the north-western part of the Istrian peninsula (Zone B) was given to Yugoslavia.[82]

The Italian government was harshly criticized for signing the treaty, particularly for the secretive way in which negotiations were carried out, skipping the traditional diplomatic channels. Italian nationalists of the MSI rejected the idea of giving up Istria, since Istria had been an ancient "Italian" region together with the Venetian region (Venetia et Histria).[83] Furthermore, Istria had belonged to Italy for 25 years between World War I and the end of World War II, and the west coast of Istria had long had a sizeable Italian minority population.[84]

Some nationalist politicians called for the prosecution of Moro and his Foreign Affairs Minister, Rumor, for the crime of treason, as stated in Article 241 of the Italian Criminal Code, which mandated a life sentence for anybody found guilty of aiding and abetting a foreign power to exert its sovereignty on the national territory.[85]

Resignation

Despite the tensions within government's majority, the close relations between Moro and the communist leader, Enrico Berlinguer, guaranteed a certain stability to Moro's governments, allowing them a capacity to act that went beyond the premises that had seen them born.[86]

The fourth Moro government, with Ugo La Malfa as Deputy Prime Minister, started a first dialogue with the PCI, with the aim of beginning a new phase to strengthen the Italian democratic system.[87] However, in 1976 the PSI secretary, Francesco De Martino, withdrew the external support to the government and Moro was forced to resign.[88]

Historic compromise

After the 1976 general election, the PCI gained a historic 34% votes and Moro became a vocal supporter of the necessity of starting a dialogue between DC and PCI.[89] Moro's main aim was to widen the democratic base of the government, including the PCI in the parliamentary majority: the cabinets should have been able to represent a larger number of voters and parties. According to him, the DC should have been as the centre of a coalition system based on the principles of consociative democracy.[90] This process was known as Historic Compromise.[91]

Between 1976 and 1977, Berlinguer's PCI broke with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, implementing, with Spanish and French communist parties, a new political ideology known as Eurocommunism. Such a move made an eventual cooperation more acceptable for Christian democratic voters, and the two parties began an intense parliamentary debate, in a moment of deep social crises.[92]

In 1977, Moro was personally involved in international disputes. He strongly defended his long-time friend, Mariano Rumor, during the parliamentary debate on the Lockheed scandal, and some journalists reported that he might have been involved in the bribery too. The allegation, with the aim of politically destroying Moro and avoiding the risk of a DC–PCI–PSI cabinet, failed when Moro was cleared on 3 March 1978, 13 days before his kidnapping.[93]

The early-1978 proposal by Moro of starting a cabinet composed by Christian democrats and socialists, externally supported by the communists was strongly opposed by both superpowers. The United States feared that the cooperation between PCI and DC might have allowed the communists to gain information on strategic NATO military plans and installations.[94] Moreover, the participation in government of the communists in a Western country would have represented a cultural failure for the USA. On the other hand, the Soviets considered the potential participation by the Italian Communist Party in a cabinet as a form of emancipation from Moscow and rapprochement to the Americans.[95]

Kidnapping and death

On 16 March 1978, on Via Fani, in Rome, a unit of the militant far-left organisation known as Red Brigades (BR) blocked the two-car convoy which were carrying Moro and kidnapped him, murdering his five bodyguards.[96] On the day of his kidnapping, Moro was on his way to a session of the Chamber of Deputies, where a discussion was to take place regarding a vote of confidence for a new government led by Giulio Andreotti that would have, for the first time, the support of the Communist Party. It was to be the first implementation of Moro's strategic political vision.[97]

In the following days, trade unions called for a general strike, while security forces made hundreds of raids in Rome, Milan, Turin, and other cities searching for Moro's location. After a few days, even Pope Paul VI, a close friend of Moro's, intervened,[98] offering himself in exchange for Aldo Moro.[99]

Negotiations and captivity letters

The Red Brigades proposed exchanging Moro's life for the freedom of several prisoners.[3] There has been speculation that during his detention, many knew where he was hidden. The government immediately took a hard line position: the "State must not bend to terrorist demands". However, this position was openly criticised by prominent Christian Democracy party members such as Amintore Fanfani and Giovanni Leone, who at the time was serving as President of Italy.[100]

On 2 April Romano Prodi, Mario Baldassarri,[101] and Alberto Clò, three professors of the University of Bologna, passed on a tip about a safe-house where the Red Brigades might have been holding Moro. Prodi claimed he had been given the tip by the founders of the Christian Democrats, from beyond a grave in a séance and a Ouija board, which gave the names of Viterbo, Bolsena and Gradoli.[102]

During the investigation of Moro's kidnapping, some members of law enforcement and of the secret services advocated for the use of torture against terrorists, but prominent military like General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa were against this. Dalla Chiesa once stated: "Italy can survive the loss of Aldo Moro, but it would not survive the introduction of torture."[103][104][105]

During his kidnapping, Moro wrote several letters to the leaders of the Christian Democrats and to Pope Paul VI, who later personally officiated in Moro's funeral mass. Some of those letters, as one that was very critical of Giulio Andreotti, were kept secret for more than a decade, and published only in the early 1990s.[3]

In his letters, Moro said that the state's primary focus should be saving lives and that the government should comply with his kidnappers' demands. Most of the DC's leaders argued that the letters did not express Moro's genuine wishes, claiming they were written under duress, and thus refused all negotiations. This position was in stark contrast to the requests of Moro's family. In his appeal to the terrorists, Pope Paul VI asked them to release Moro "without conditions".[106]

Murder

When it became clear that the government did not want to negotiate, the Red Brigades had a "people's trial", in which Moro was found guilty and sentenced to death. Then they sent a last demand to the Italian authorities, stating that if 16 Red Brigades prisoners were not released, Moro would be killed. The Italian authorities responded with a large-scale manhunt, which was useless.[107]

On 9 May 1978, the terrorists placed Moro in a car and told him to cover himself with a blanket, saying that they were going to transport him to another location.[108] After Moro was covered they shot him ten times. According to the official reconstruction after a series of trials, the killer was Mario Moretti. Moro's body was left in the trunk of a red Renault 4 on Via Michelangelo Caetani towards the Tiber River near the Roman Ghetto.[109]

After the recovery of Moro's body, the Minister of the Interior, Francesco Cossiga, resigned.

New revelations and controversies

In 2005, Sergio Flamigni, a leftist politician and writer, who had served on a parliamentary inquiry on the Moro case, suggested the involvement of the Operation Gladio network directed by NATO. He asserted that Gladio had manipulated Moretti as a way to take over the BR in order to effect a strategy of tension aimed at creating popular demand for a new, right-wing law-and-order regime.[110][111]

In 2006, the Harvard and MIT educated American psychiatrist and former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Management, Steve Pieczenik, was interviewed by Emmanuel Amara in his documentary film Les derniers jours d'Aldo Moro ("The Last Days of Aldo Moro"). In the interview, Pieczenik, an expert on international terrorism and negotiating strategies who had been brought to Italy as a consultant to Interior Minister Francesco Cossiga's Crisis Committee, stated that: "We had to sacrifice Aldo Moro to maintain the stability of Italy."[112][113]

Pieczenik maintained that the U.S. had had to "instrumentalize the Red Brigades." According to him, the decision to have Moro killed was taken during the fourth week of his detention, when Moro was thought to be revealing state secrets in his letters,[114] namely, the existence of Gladio.[113] In another interview former interior minister Cossiga revealed that the Crisis Committee had also leaked a false statement attributed to the Red Brigades that Moro was already dead. This was intended to communicate to the kidnappers that further negotiations would be useless, since the government had written Moro off.[115][116]

In April 2015, it was reported that controversies around Moro could cause the suspension or closing of the cause. The postulator has stated the cause will continue when the discrepancies are cleared up.[117] The halting of proceedings was due to Antonio Mennini, the priest who heard his last confession, being allowed to provide a statement to a tribunal in regards to Moro's kidnapping and confession. The cause was able to resume its initial investigations following this.

Legacy

As a Christian democrat with social democratic tendencies, Moro is widely considered one of the ideological fathers of modern Italian centre-left.[118] During all his political life, he implement numerous reforms which deeply changed Italian social life; along with his long-time friend and, at the same time, opponent, Amintore Fanfani, he was the protagonist of a long-standing political phase, which brought the social conservative DC towards more leftist politics, through a cooperation with the Italian Socialist Party first, and the Italian Communist Party later.[119]

Due to his reformist stances but also for his tragic death, Moro has often been compared to John F. Kennedy and Olof Palme.[120]

According to media reports on 26 September 2012, the Holy See has received a file on beatification for Moro; this is the first step to become a saint in the Roman Catholic Church.[121]

Electoral history

| Election | House | Constituency | Party | Votes | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | Constituent Assembly | Bari–Foggia | DC | 27,801 | ||

| 1948 | Chamber of Deputies | Bari–Foggia | DC | 62,971 | ||

| 1953 | Chamber of Deputies | Bari–Foggia | DC | 39,007 | ||

| 1958 | Chamber of Deputies | Bari–Foggia | DC | 154,411 | ||

| 1963 | Chamber of Deputies | Bari–Foggia | DC | 227,570 | ||

| 1968 | Chamber of Deputies | Bari–Foggia | DC | 293,167 | ||

| 1972 | Chamber of Deputies | Bari–Foggia | DC | 178,475 | ||

| 1976 | Chamber of Deputies | Bari–Foggia | DC | 166,260 | ||

Cinematic adaptations

A number of films have portrayed the events of Moro's kidnapping and murder with varying degrees of fictionalization including the following:

- Todo modo (1976), directed by Elio Petri, based on a novel by Leonardo Sciascia, actually made before Moro's kidnapping

- Il caso Moro (1986), directed by Giuseppe Ferrara and starring Gian Maria Volonté as Moro

- Year of the Gun (1991), directed by John Frankenheimer

- Broken Dreams (Sogni infranti, 1995), a documentary directed by Marco Bellocchio

- Five Moons Plaza (Piazza Delle Cinque Lune, 2003), directed by Renzo Martinelli and starring Donald Sutherland

- Good Morning, Night (Buongiorno, notte, 2003), directed by Marco Bellocchio, portrays the kidnapping largely from the perspective of one of the kidnappers

- Romanzo Criminale (2005), directed by Michele Placido, portrays the authorities finding Moro's body

- Les derniers jours d'Aldo Moro (The Last Days of Aldo Moro, 2006)

- Il Divo (2008): La Straordinaria vita di Giulio Andreotti, directed by Paolo Sorrentino, highlighting the responsibility of Giulio Andreotti

- Piazza Fontana: The Italian Conspiracy (2012) (Romanzo di una strage) directed by Marco Tullio Giordana, Aldo Moro portrayed by actor Fabrizio Gifuni

References

- Aldo Moro, Enciclopedia Treccani

- Aldo Moro – Biografia, Mondi

- Il rapimento Moro, Rai Scuola

- "[Pillole di storia italiana] Le riforme del primo centrosinistra: Moro tessitore d'Italia". 29 November 2008.

- La lezione di Aldo Moro quarant'anni dopo, Voce Tempo

- Biografia di Aldo Moro, Biografie Online

- Biografia, Aldo Moro

- FUCI – Sito Ufficiale della Federazione Universitaria Cattolica Italiana, www.fuci.net

- Renato Moro, Aldo Moro negli anni della FUCI, Studium 2008; Tiziano Torresi L'altra giovinezza. Gli universitari cattolici dal 1935 al 1940, Cittadella editrice 2010.

- Vi racconto la storia dimenticata del giovane Aldo Moro di destra, Corriere del Mezzogiorno

- Il Codice di Camaldoli, Giuseppe Capograssi

- The Turn of Camaldoli , in State and Economy , then resumed with the same intent in Paolo Emilio Taviani, Because the Code of Camaldoli was a turning point in " Civitas ", XXXV. July–August 1984.

- Rinaldi, Marcello (2006). From the welfare state to the welfare society. Social Theology and Pastoral Action of Italian Caritas , Effatà Editrice. ISBN 88-7402-301-4.

- Morta Eleonora Chiavarelli, la moglie di Aldo Moro, Famiglia Cristiana

- "30Giorni | Ricordare Piccioni (Giulio Andreotti)". www.30giorni.it.

- La «santità» di Aldo Moro secondo Dossetti, Avvenire

- Aldo Moro: autentico innovatore, Azione Cattolica

- "Aldo Moro, Intervento all'Assemblea Costituente" (PDF).

- Elezioni 1946: Circoscrizione Bari–Foggia, Ministero dell'Interno

- Elezioni 1948: Circoscrizione Bari–Foggia, Ministero dell'Interno]

- Governo De Gasperi V, www.governo.it

- Storia della Democrazia Cristiana. Le correnti, Storia DC

- Elezioni del 1953: Circoscrizione Bari–Foggia, Ministero dell'Interno

- Governo Segni I, governo.it

- I Governo Segni, camera.it

- Governo Zoli, camera.it

- Governo Fanfani II, senato.it

- L'ora mancante di Educazione Civica, Corriere della Sera

- Ritorno a scuola, educazione civica in 33 ore, Il Sole 24 Ore

- Scuola, il Parlamento prepara il ritorno in grande stile dell'educazione civica, Adnkronos

- Il Doroteismo, In Storia

- VII Congresso Nazionale della Democrazia Cristiana, Storia DC

- VIII Congresso di Napoli, Della Repubblica

- Elezioni del 1963, Ministero dell'Interno

- I Governo Leone, camera.it

- I Governo Moro, governo.it

- Sabattini, Gianfranco (28 November 2011). "Cinquant'anni fa nasceva il centrosinistra poi arrivarono i 'nani' della politica". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- Legge "Ponte" n. 765/1967 del 6 agosto 1967 (GU n. 218 del 31-8-1967), Studio Tecnico Pagliai

- "Il centrosinistra e le riforme degli anni '60". 22 January 2018.

- "Il centro-sinistra e i governi Moro - Istituto Luigi Sturzo". old.sturzo.it.

- La svolta di Aldo Moro: i governi di centrosinistra, Il Giornale

- Growth to Limits: The Western European Welfare States Since World War II Volume 4 edited by Peter Flora.

- Il 9 settembre 1963 il disastro del Vajont: commemorazioni in tutta la regione, Friuli Venezia Giulia

- "Vaiont Dam photos and virtual field trip". University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- La cronaca del disastro e il processo, ANSA

- La tragedia del Vajont, Rai Scuola

- "Mattolinimusic.com". Mattolinimusic.com. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "Vajont, Due Volte Tragedia". Sopravvissutivajont.org. 9 October 2002. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- Un banco di prova. La legislazione sul Vajont dalle carte di Giovanni Pieraccini (1963–1964)

- Indro Montanelli, Storia d'Italia Vol. 10, RCS Quotidiani, Milan, 2004, page 379-380.

- Gianni Flamini, L'Italia dei colpi di Stato, Newton Compton Editori, Rome, page 82.

- Sergio Romano, Cesare Merzagora: uno statista contro I partiti, in: Corriere della Sera, 14 marzo 2005.

- Governo Moro II, governo.it

- Segni, uomo solo tra sciabole e golpisti, Il Fatto Quotidiano

- Tempers Flare as Italian Parliament Fails to Elect New President, Retrospective Blog

- I Presidenti – Giuseppe Saragat, Camera dei Deputati

- Elezioni del 1968, Ministero dell'Interno

- Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1048 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- V Legislatura della Repubblica italiana, Camera dei Deputati

- Governo Rumor II, governo.it

- Appunti trasmessi dalla Presidenza del Consiglio con missiva, 27 January 1998.

- Aldo Moro, il vero artefice della svolta verso il mondo arabo, Welfare Network

- Sergio Flamigni, La tela del ragno. Il delitto Moro (page 197-198), Kaos edizioni, 2003.

- Tribunale di Venezia, procedimento penale nº204 del 1983, page 1161-1163.

- “Fu il Lodo Moro a tenere gli italiani al sicuro a Beirut nell’82”, La Stampa

- Corriere della Sera, 14 August 2008, page 19

- Aldo Moro, parla Abu Sharif: «Un mese prima del sequestro Moro ho dato io l’allarme a Roma», Corriere della Sera

- Corriere della Sera, 15 August 2008, page 21

- Mastelloni : “Così nel ’71 bloccammo un golpe Gheddafi”, La Stampa

- Aldo Moro – Dizionario Biografico, Enciclopedia Treccani

- Corsa al Quirinale: l'elezione di Giovanni Leone, Panorama

- L'elezione del Presidente Leone, quirinale.it

- Elezione del Presidente della Repubblica, 1971, Senato della Repubblica

- Ed Vulliamy (4 March 2007). "Blood and glory" (XHTML). The Observer. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- Strage dell'Italicus, Associazione Italiana Vittime del Terrorismo

- «Moro salì sull'Italicus ma fu fatto scendere», Corriere della Sera

- Italicus: storia di un mistero italiano in dieci punti, Linkiesta

- Paul, Hofman. "RUMOR'S CABINET RESIGNS IN ITALY". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- Shenker, Israel. "RUMOR'S CABINET RESIGNS IN ITALY". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- IV Governo Moro – Coalizione politica DC–PRI, Della Republica

- Aldo Moro: uomo del riformismo e del compromesso, Falsa Riga

- The Europa World Year, Taylor & Francis Group

- Ronald Haly Linden (2002). Norms and nannies: the impact of international organizations on the central and east European states. p. 104. ISBN 9780742516038.

- Valussi, Ressmann (1861). Trieste e l'Istria nelle quistione italiana. p. 62.

- Aldo Moro e la ferita del Trattato di Osimo, Il Piccolo

- Berlinguer, teoria e tecnica del compromesso storico, Rai Storia

- Compromesso storico, Enciclopedia Treccani

- Governo Moro V, governo.it

- Elezioni del 1976, Ministero dell'Interno

- Fontana, Sandro (1982). "Moro e il sistema politico italiano" (PDF). Cultura e politica nell'esperienza di Aldo Moro (in Italian). Milan: Giuffrè. pp. 183–184.

- "Cos'è il compromesso storico? | Sapere.it". www.sapere.it.

- Eurocomunismo, Enciclopedia Treccani

- Wagner-Pacifici, Robin Erica (1986). The Moro Morality Play. Terrorism as Social Drama. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 30–32., Cucchiarelli, Paolo; Aldo Giannuli (1997). Lo Stato parallelo. Rome: Gamberetti Editrice. p. 422.

- Quanti rimpianti da quella stretta di mano tra Moro e Berlinguer, Giornale Mio

- Quando c'era Berlinguer. Bureau. 21 May 2015. ISBN 9788858680681 – via Google Books.

- Tutto quel che non torna del rapimento di Aldo Moro, Linkiesta

- Governo Andreotti IV, governo.it

- 1978: Aldo Moro snatched at gunpoint, "On This Day", BBC (in English)

- Holmes, J. Derek, and Bernard W. Bickers. A Short History of the Catholic Church. London: Burns and Oates, 1983. 291.

- Leone mi raccontò perché non riuscì a salvare Moro, Il Dubbio

- 17 June 1998 hearing of the Commissione parlamentare d'inchiesta sul terrorismo in Italia e sulle cause della mancata individuazione dei responsabili delle stragi directed by senator Giovanni Pellegrino (in Italian)

- Popham, Peter (2 December 2005). "The seance that came back to haunt Romano Prodi". The Independent. London. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- This is the widely cited translation. Original Italian: L'Italia è un Paese democratico che poteva permettersi il lusso di perdere Moro non di introdurre la tortura, "Italy is a democratic country that could allow itself the luxury of losing Moro, [but] not of the introduction of torture." Source

- Report of Conadep (National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons): Prologue – 1984

- Quoted in Dershowitz, Alan M. Why Terrorism Works, p.134, ISBN 978-0-300-10153-9

- "L'appello di Paolo VI per il rilascio di Moro". Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- 100 Years of Terror, documentary by History Channel

- Aldo Moro, 40 anni fa il sequestro del presidente della Dc, ANSA

- Fasanella, Giovanni; Giuseppe Roca (2003). The Mysterious Intermediary. Igor Markevitch and the Moro affair. Einaudi.

- Giovanni Fasanella and Alberto Franceschini (with a postscript by Judge Rosario Priore, a judge in the Moro case), Che cosa sono le Brigate Rosse ("What are the Red Brigades"), Published in French as Brigades rouges: L'histoire secrète des BR racontée par leur fondateur (Red Brigades: The secret [hi]story of the RBs, recounted by their founder), Alberto Franceschini, with Giovanni Fasanella. Editions Panama, 2005, ISBN 2-7557-0020-3.

- Omicidio Pecorelli – Andreotti condannato, La Repubblica, 17 November 2002 (in Italian)

- Emmanuel Amara, Les derniers jours d'Aldo Moro (The Last Days of Aldo Moro), Interview of Steve Pieczenik put on-line by Rue 89

- Hubert Artus, Pourquoi le pouvoir italien a lâché Aldo Moro, exécuté en 1978 (Why the Italian Power let go of Aldo Moro, executed in 1978), Rue 89, 6 February 2008 (in French)

- Emmanuel Amara, Les derniers jours d'Aldo Moro (The Last Days of Aldo Moro), Interview of Steve Pieczenik & Francesco Cossiga put on-line by Rue 89

- Moore, Malcolm (11 March 2008). "US envoy admits role in Aldo Moro killing". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- "Europa nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg:Freiheitliche Demokratien oder Satelliten der USA?" (in German). .zeit-fragen.ch. 9 June 2008. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- "Controversies around Aldo Moro risks a stop for beatification (in Italian)". Corriere del Mezzogiorno. 24 April 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- "Il centro-sinistra di Aldo Moro - Marsilio Editori". www.marsilioeditori.it.

- E Moro divenne «Padre della Patria», Avvenire]

- GIANGRANDE, ANTONIO. "LA VICENDA ALDO MORO: QUELLO CHE SI DICE E QUELLO CHE SI TACE". Antonio Giangrande – via Google Books.

- "Murdered Italian PM Aldo Moro 'could be beatified'". The Daily Telegraph. London. 26 September 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

Further reading

- Drake, Richard (1996). The Aldo Moro Murder Case. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01481-2.

- Hof, Tobias. The Moro Affair – Left-Wing Terrorism and Conspiracy in Italy in the Late 1970s. Historical Social Research, vol. 38 (2013), no. 1, pp. 129–141 (PDF).

- Wagner-Pacifici, Robin. The Moro morality play: Terrorism as social drama (University of Chicago Press, 1986).

- Pasquino, Gianfranco. Aldo Moro. In: Wilsford, David, ed. Political leaders of contemporary Western Europe: a biographical dictionary (Greenwood, 1995) pp. 339–45.

Primary sources

- Interview with Giovanni Moro, Aldo Moro's son by La Repubblica, 16 March 1998.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aldo Moro. |

- Craveri, Piero (2012). "Moro, Aldo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 77: Morlini–Natolini (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. pp. 16–29.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Michele De Pietro |

Minister of Justice 1955–1957 |

Succeeded by Guido Gonella |

| Preceded by Paolo Rossi |

Minister of Public Education 1957–1959 |

Succeeded by Giuseppe Medici |

| Preceded by Giovanni Leone |

Prime Minister of Italy 1963–1968 |

Succeeded by Giovanni Leone |

| Preceded by Giuseppe Saragat |

Minister of Foreign Affairs Acting 1964–1965 |

Succeeded by Amintore Fanfani |

| Preceded by Amintore Fanfani |

Minister of Foreign Affairs Acting 1965–1966 | |

| Preceded by Pietro Nenni |

Minister of Foreign Affairs 1969–1972 |

Succeeded by Giuseppe Medici |

| Preceded by Giuseppe Medici |

Minister of Foreign Affairs 1973–1974 |

Succeeded by Mariano Rumor |

| Preceded by Mariano Rumor |

Prime Minister of Italy 1974–1976 |

Succeeded by Giulio Andreotti |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Amintore Fanfani |

Secretary of the Christian Democracy 1959–1964 |

Succeeded by Mariano Rumor |

| President of the Christian Democracy 1976–1978 |

Succeeded by Flaminio Piccoli | |

.svg.png.webp)