Felice Napoleone Canevaro

Felice Napoleone Canevaro (7 July 1838 – 30 December 1926) was an Italian admiral and politician and a senator of the Kingdom of Italy. He served as both Minister of the Navy and Minister of Foreign Affairs and was a recipient of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus. In his naval career, he was best known for his actions during the Italian Wars of Independence and later as commander of the International Squadron off Crete in 1897–1898.

Felice Napoleone Canevaro | |

|---|---|

Felice Napoleone Canevaro in 1898 | |

| Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 29 June 1898 – 14 May 1899 | |

| Monarch | Umberto I |

| Prime Minister | Luigi Pelloux |

| Preceded by | Raffaele Cappelli |

| Succeeded by | Emilio Visconti Venosta |

| Italian Minister of the Navy | |

| In office 1 June 1898 – 29 June 1898 | |

| Monarch | Umberto I |

| Prime Minister | Antonio di Rudini |

| Preceded by | Alessandro Assinari di San Marzano |

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Palumbo |

| Senator of the Kingdom of Italy | |

| Monarch | Umberto I XIX Legislature |

Biography

The descendant of a Ligurian family originally from Zoagli, Canevaro was born in Lima, Peru, to Giuseppe and Francesca Velaga.[1]

Naval career

In 1852, Canevaro was admitted to the Kingdom of Sardinia's Royal Navy School at Genoa, completing the course of instruction in 1855 and receiving a commission as an ensign second class.

Italian Wars of Independence

In 1859, with the rank of second lieutenant, Canevaro took part in Royal Sardinian Navy operations in the Adriatic Sea aboard the transport Beroldo and the sailing frigate Des Geneys during the Second Italian War of Independence.[1]

In 1860, Canevaro arrived in Palermo, Sicily, aboard Maria Adelaide, the flagship of the Sardinian squadron. When the supporters of the Italian nationalist leader General Giuseppe Garibaldi organized their navy, he resigned from the Royal Sardinian Navy to enlist in the Garibaldian navy. Aboard the steam frigate Tukory on the night of 13 August 1860, Canevaro distinguished himself during an unsuccessful attempt to board the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies steam ship-of-the-line Monarca while she was anchored in the port of Castellammare di Stabia. He received the Silver Medal of Military Valor for his actions during this engagement.[1]

In the autumn of 1860, Canevarro was reinstated in the Royal Sardinian Navy. While embarked on the Sardinian steam frigate Carlo Alberto from December 1860 to March 1861, he took part in the Siege of Gaeta and a siege of Messina during operations in which Carlo Alberto repeatedly exchanged fire with hostile forces at close range along the coast. After the campaign, he was made a Knight of the Military Order of Savoy, and in 1863, he was promoted to luogotenente de vascello. In 1865–1866, Canevaro was on board the steam frigate Principe Umberto, under the command Guglielmo Acton, during a long cruise that included a transatlantic voyage, operations along the Atlantic coast of South America, a transit of the Strait of Magellan into the Pacific Ocean, and steaming up the coast of Chile.[1]

On returning to Italy, he was assigned to the broadside ironclad Re di Portogallo, commanded by Augusto Riboty. Aboard Re di Portogallo, he took part in 1866 in the Third Italian War of Independence, during which the ship was engaged in operations against the fortress of Lissa in the Adriatic Sea. As flagship of the 3rd Division, and with Canevaro aboard as the division's chief-of-staff, Re di Portogallo led the division's attack on Porto San Giorgio on 18 July 1866.[1]

Felice Napoleono Canevaro | |

|---|---|

| Born | 7 July 1838 Lima, Peru |

| Died | 30 December 1926 (aged 88) Venice, Italy |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1852–1903 |

| Rank | Vice Admiral |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars |

|

Duke of Castelvari and Zoagli | |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Canevaro |

| Personal details | |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Spouse(s) | Ersilia Cozzi |

| Children | Giuseppe Canevaro |

| Parents | Giuseppe and Francesca Velaga |

| Title | Duke of Castelvari and Zoagli |

| Tenure | ? –30 December 1926 |

| Other titles | Count of Santander |

Battle of Lissa

On 20 July 1866, Re di Portogallo played a particularly prominent role in the Battle of Lissa against the Austrian fleet.[1] She first opened fire on the Austrian steam corvette SMS Erzherzog Friedrich, scoring a hit below the waterline that opened a leak that caused more water to enter Erzherzog Friedrich than her pumps could handle, forcing Erzherzog Friedrich to retreat in the direction of Lissa. While chasing the damaged Erzherzog Friedrich, Re di Portogallo sighted the Austrian steam ship-of-the-line SMS Kaiser, which, although seriously damaged by a broadside fired by the Italian ironclad ram Affondatore, was approaching to defend Erzherzog Friedrich.[2][3] Re di Portogallo attempted to ram Kaiser, but Kaiser steered toward Re di Portogallo and the two ships collided violently head-on.[2] Kaiser had the worst of the collision, which badly damaged her bow, destroyed her bowsprit, and left her figurehead, a wooden statue of the Austrian emperor Kaiser Franz Joseph I, stuck in the hull of Re di Portogallo; it became an Italian war trophy.[2][3] Entangled with Kaiser, Re di Portogallo pummeled her with gunfire at close range, inflicting many casualties on her crew and bringing down her foresail, which crashed onto her funnel. Re di Portogallo put her engines astern to pull away from Kaiser and maneuver to ram her again, but could not resume her attack because smoke had concealed Kaiser, which the officers of Re di Portogallo mistakenly believed may have sunk. As the battle continued Re di Portogallo found herself surrounded by four Austrian ships, but she managed to escape from them thanks to the ability of her commander, Riboty.[2] One of the Italian ships most heavily involved in the battle,[1] Re di Portogallo suffered serious damage, including the loss of her anchors and some of her boats and having 18 metres (59 ft) of her armor dislodged, most of this damage occurring during the duel with Kaiser. Although the outcome of the Battle of Lissa ultimately was disastrous for the Italian fleet,[2] Canevaro received a second award of the Silver Medal for Military Valor,[1] while Re di Portogallo's commanding officer Riboty received the Gold Medal of Military Valor.[4]

1870s–1890s

Promoted to capitano di fregata in 1869, Canevaro served as a naval attaché at the Italian embassy in London from March 1874 to August 1876. From January 1877 to March 1879, while in command of the cruiser Colombo, he circumnavigated the globe, departing Italy, transiting the Suez Canal, skirting Asia, visiting ports in China and the Netherlands East Indies – where Colombo recovered the body of the Italian general and politician Nino Bixio, who had died of cholera in Banda Aceh on Sumatra in 1873 – and then went on to Japan, Russia (including Siberia), Australia and the Americas. After transiting the Strait of Magellan into the Atlantic Ocean, Colombo steamed up the coast of South America to the Caribbean, then crossed the Atlantic to return to Italy.[1]

Promoted to capitano di vascello, Canevaro performed various important duties, including service as chief-of-staff of the 3rd Maritime Department headquartered at Venice, second-in-command of the Italian Naval Academy, and commanding officer of the ironclad battleship Italia. In 1884, while in command of Italia, he played an active role in humanitarian work and public health during a cholera epidemic in La Spezia, and he received the Silver Medal for Civil Valor for these efforts.[1]

Promoted to counter admiral (the equivalent of rear admiral) in 1887,[1] Canevaro assumed command of the arsenal of Taranto and later of the 2nd Naval Division of the Permanent Squadron.[1] He was promoted to vice admiral in 1893,[1] and King Umberto I appointed him a Senator of the Kingdom of Italy – an appointment for life – in 1896,[1] the same year in which he assumed command of the Regia Marina's Naval Squadron.

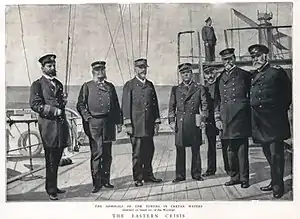

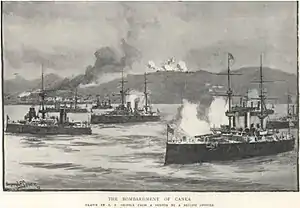

International Squadron

In February 1897, when a Christian uprising against the authority of the Ottoman Empire broke out on the island of Crete, Canevaro arrived at Crete in command of the 1st Division of the 1st Squadron, consisting of the ironclad battleships Sicilia (his flagship) and Re Umberto, the protected cruiser Vesuvio, and the torpedo cruiser Euridice. Canevaro – who relieved the commander of the Italian naval squadron, Rear Admiral Gualterio, who had previously been in command of the 2nd Naval Division – assumed command of the International Squadron of warships off Crete on 16 or 17 February 1897 (sources differ) as the most senior admiral present, and took up duties as president of the "Admirals Council," which consisted of the senior admirals present off Crete of each of the six countries participating in the International Squadron.[1][5] The squadron put landing detachments ashore, but Christian insurgents continued to attack Ottoman forces and Canevaro soon ordered International Squadron ships to bombard them during February and March 1897 to stop the fighting. Although some political opponents in the Italian legislature attacked him for ordering the International Squadron to bombard the insurgents, Canevaro received great credit during his time in command of the squadron for his ability to exercise diplomacy and mediate disputes between the six Great Powers – Austria-Hungary, France, the German Empire, Italy, the Russian Empire, and the United Kingdom – making up the squadron and for the way in which he dealt with the confusing and anarchic situation on Crete, balancing humanitarian compassion and a spirit of conciliation in his dealings with Greek, Christian insurgent, and Ottoman forces on the island with the occasional need to use force to halt fighting and quell disturbances. Before leaving the International Squadron in 1898, Canevaro negotiated an agreement under which all combat on Crete would cease and Greece and the Ottoman Empire would withdraw their forces from the island in anticipation of the creation of an autonomous Cretan State under the suzerainty of the Ottoman sultan.[1] Such was his reputation that when the creation of an office of High Commissioner of the Cretan State was proposed in the spring of 1898, Canevaro received an invitation to become the first high commissioner, but he declined the offer, and instead Prince George of Greece and Denmark became the first high commissioner when the Cretan State finally came into existence in December 1898.[1]

Government minister

When Prime Minister of Italy Antonio Starabba, Marchese di Rudinì, formed the government for his fifth ministry, Canevaro turned over command of the International Squadron to its next-most-senior admiral, Rear Admiral Édouard Pottier of the French Navy, and returned to Italy to serve as di Rudini′s Minister of the Navy. Taking office on 1 June 1898, he served only four weeks, until the di Rudini government was replaced on 29 June 1898 by that of Prime Minister General Luigi Pelloux. On the same day Pelloux took office, Canevaro changed portfolios to become the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs.[1] In his new role, he attempted to continue Italy′s policy of loyalty to the Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and the German Empire and of continued warm relations with the United Kingdom, but at the same time worked toward relaxing tensions with France, and he conducted secret negotiations with the French for a commercial treaty, which the countries signed on 26 November 1898. He also resisted pressure from Germany to change the status of the Cretan State, supporting its continuation as an autonomous state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire.[1]

However, despite his successes in negotiations on Crete while in command of the International Squadron, Canevaro's talent for leading military forces did not translate into success in international diplomacy when it came to larger issues. During the Fashoda Crisis of 1899 between France and the United Kingdom, Canevaro conducted intensive diplomacy as part of the ongoing European "Scramble for Africa" in an effort to gain French and British recognition of an Italian interest in Libya, but when the French and British concluded an agreement on 21 March 1899 that resolved the crisis, they offered no such recognition. Canevaro also was unsuccessful when in the wake of a number of anarchist attacks in Europe – one of which resulted in the stabbing death of Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary Elizabeth on 10 September 1898 – he proposed an international anti-anarchist conference of diplomats and government security and judicial officials to address the situation; although some countries agreed to participate, the conference never took place.[1]

A final blow to Canevaro's diplomatic career came in the "San Mun Affair" of 1899, in which Italy demanded that the Chinese Empire grant it a lease for a naval coaling station at China's Sanmen Bay (known as "San-Mun Bay" to the Italians) similar to the lease the German Empire had secured in 1898 at Kiaochow Bay.[6] [7]From Sanmen Bay, Italy hoped to establish an area of influence in Chekiang. The Russian Empire and the United States opposed the Italian demand, but the Italian ambassador in China, Renato De Martino, led Canevaro to believe that the area was ripe for the taking. The British government, although ambivalent toward the Italian move, gave its approval as long as Italy did not use force against the Chinese, but the British did not inform Canevaro that the United Kingdom′s representatives in China had advised that Italy could not achieve its goals without using force. Believing the opportunity to pursue Italy's interests in China was at hand, Canevaro had de Martino pass Italy′s demands to the Chinese imperial government in the winter of 1899, but the Chinese summarily rejected them on 4 March 1899. On 8 March, Canevaro instructed De Martino to present the demands again as an ultimatum and authorized the armored cruiser Marco Polo and protected cruiser Elba to occupy the bay. When the British ambassador in Rome reminded him that the United Kingdom did not support an Italian use of force, Canevaro issued a counterorder cancelling his authorization to use the two cruisers in the bay, but De Martino received the counterorder before he received the original authorization to employ the ships. Unable to decipher the counterorder, De Martino presented the Italian ultimatum to China again on 10 March 1899, and China immediately refused to comply. Italy withdrew its ultimatum, becoming at the end of the 19th century the first and only Western power to fail to achieve its territorial goals in China. The fiasco was an embarrassment that gave Italy – still stung by its defeat at the hands of the Ethiopian Empire in the Battle of Adowa in 1896 – the appearance of a third-rate power. On 14 March 1899, Canevaro attempted to present the affair to the Italian Parliament in a positive light, saying that be believed that China had rejected the Italian ultimatum in order to maintain a positive and productive relationship with Italy uninterrupted by negotiations over the bay, but such was the domestic criticism of the Italian failure as a humiliation and international criticism of it as a needless and unjustified provocation that Pelloux announced the resignation of his entire cabinet on 14 May 1899.[6] He excluded Canevaro from the new cabinet he established that day.[1][8]

Later naval service

Canevaro returned to the navy, commanding the 3rd Maritime District from 16 July 1900 to 16 January 1902 and presiding over the Supreme Council of the Navy from 16 January 1902 until 6 July 1903. He then retired and was placed on the reserve list, although in retirement he was promoted to vice admiral of the navy on 1 December 1923. He died at Venice on 30 December 1926.[1]

Awards and honors

Italian awards and honors

![]() Knight of the Grand Cross decorated with the Great Cordon of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

Knight of the Grand Cross decorated with the Great Cordon of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

![]() Knight of the Grand Cross decorated with the Great Cordon of the Order of the Crown of Italy

Knight of the Grand Cross decorated with the Great Cordon of the Order of the Crown of Italy

![]() Commander of the Military Order of Savoy

Commander of the Military Order of Savoy

![]() Silver Medal of Military Valour (two awards)

Silver Medal of Military Valour (two awards)

![]() Commemorative Medal for the Campaigns of the War of Independence (with three bars)

Commemorative Medal for the Campaigns of the War of Independence (with three bars)

Foreign awards and honors

![]() Order of Isabella the Catholic (Kingdom of Spain)

Order of Isabella the Catholic (Kingdom of Spain)

![]() Commander of the Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa (Kingdom of Portugal)

Commander of the Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa (Kingdom of Portugal)

![]() Commemorative medal of the 1859 Italian Campaign (Second French Empire)

Commemorative medal of the 1859 Italian Campaign (Second French Empire)

In popular culture

Canevaro (spelled "Canavaro") is mentioned in Nikos Kazantzakis's novel Zorba the Greek and the subsequent film and musical of the same name, as the admiral and former lover of key character Madame Hortense, who thereafter calls Zorba by his name.

One of the main streets of the city center in Chania on Crete, odos Kanevarou, is named after Canevaro.

See also

References

Notes

- Mariano, Gabriele (1975). "Canevaro, Felice Napoleone". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian).

- Ermanno Martino, Lissa 1866: perché? in Storia Militare n. 214 and 215, July–August 2011 (Italian).

- Benninghof, Mike (September 2007). "Deadly Fishermen: The Battle of Lissa, 20 July 1866". Avalanche Press.

- "marina.difesa.it Augusto Riboty".

- "The Powers Take Action; Sharp Warning Issued to Prince George Against Hostilities" (PDF). The New York Times. 18 February 1897.

- Coco, Orazio (24 April 2019). "Italian diplomacy in China: the forgotten affair of Sān Mén Xiàn (1898–1899)". Journal of Modern Italian Studies. 24 (2): 328–349. doi:10.1080/1354571X.2019.1576416. S2CID 150961616.

- Coco, Orazio (22 May 2020). "German Imperialism in China: the leasehold of Kiaochow Bay (1897–1914)". The Chinese Historical Review. 26 (2): 156–174. doi:10.1080/1547402X.2020.1750231.

- Smith, Shirley Ann (2012). Imperial Designs: Italians in China, 1900–1947. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-1-61147-502-9.

[1]===Bibliography===

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Felice Napoleone Canevaro. |

| Preceded by Raffaele Cappelli |

Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Italy 1898–1899 |

Succeeded by Emilio, marquis Visconti-Venosta |

- Coco, Orazio (2017). Il colonialismo europeo in Estremo Oriente : l'esperienza politica ed economica delle concessioni territoriali in Cina. Rome: Nuova Cultura. ISBN 9788868129408.