Amphoterism

In chemistry, an amphoteric compound is a molecule or ion that can react both as an acid and as a base.[1] What exactly this can mean depends on which definitions of acids and bases are being used. The prefix of the word 'amphoteric' is derived from a Greek prefix amphi-, which means both.

One type of amphoteric species are amphiprotic molecules, which can either donate or accept a proton (H+). This is what "amphoteric" means in Brønsted-Lowry acid-base theory. Examples include amino acids and proteins, which have amine and carboxylic acid groups, and self-ionizable compounds such as water.

Metal oxides which react with both acids as well as bases to produce salts and water are known as amphoteric oxides. Many metals (such as zinc, tin, lead, aluminium, and beryllium) form amphoteric oxides or hydroxides. Amphoterism depends on the oxidation states of the oxide. Al2O3 is an example of an amphoteric oxide. Amphoteric oxides also include Lead (II) oxide, and zinc (II) oxide, among many others.[2]

Ampholytes are amphoteric molecules that contain both acidic and basic groups and will exist mostly as zwitterions in a certain range of pH. The pH at which the average charge is zero is known as the molecule's isoelectric point. Ampholytes are used to establish a stable pH gradient for use in isoelectric focusing.

Etymology

Amphoteric is derived from the Greek word amphoteroi (ἀμφότεροι) meaning "both". Related words in acid-base chemistry are amphichromatic and amphichroic, both describing substances such as acid-base indicators which give one colour on reaction with an acid and another colour on reaction with a base.[3]

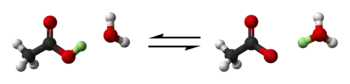

Amphiprotic molecules

According to the Brønsted-Lowry theory of acids and bases: acids are proton donors and bases are proton acceptors.[4] An amphiprotic molecule (or ion) can either donate or accept a proton, thus acting either as an acid or a base. Water, amino acids, hydrogen carbonate ion (or bicarbonate ion) HCO3−, dihydrogen phosphate ion H2PO4–, and hydrogen sulfate ion (or bisulfate ion) HSO4– are common examples of amphiprotic species. Since they can donate a proton, all amphiprotic substances contain a hydrogen atom. Also, since they can act like an acid or a base, they are amphoteric.

Examples

A common example of an amphiprotic substance is the hydrogen carbonate ion, which can act as a base:

- HCO3− + H3O+ → H2CO3 + H2O

or as an acid:

- HCO3− + OH− → CO32− + H2O

Thus, it can effectively accept or donate a proton.

Water is the most common example, acting as a base when reacting with an acid such as hydrogen chloride:

- H2O + HCl → H3O+ + Cl−,

and acting as an acid when reacting with a base such as ammonia:

- H2O + NH3 → NH4+ + OH−

Some amphiprotic compounds are also amphiprotic solvents, such as water which can act either as an acid or base depending on the solute present.[5]

Although an amphiprotic species must be amphoteric, the converse is not true. For example, the metal oxide ZnO contains no hydrogen and cannot donate a proton. Instead it is a Lewis acid whose Zn atom accepts an electron pair from the base OH−. The other metal oxides and hydroxides mentioned above also function as Lewis acids rather than Brønsted acids.

Oxides

Zinc oxide (ZnO) reacts with both acids and with bases:

- In acid: ZnO + H2SO4 → ZnSO4 + H2O

- In base: ZnO + 2 NaOH + H2O → Na2[Zn(OH)4]

This reactivity can be used to separate different cations, such as zinc(II), which dissolves in base, from manganese(II), which does not dissolve in base.

Lead oxide (PbO):

- In acid: PbO + 2 HCl → PbCl2 + H2O

- In base: PbO + 2 NaOH + H2O → Na2[Pb(OH)4]

Aluminium oxide (Al2O3)

- In acid: Al2O3 + 6 HCl→ 2 AlCl3 + 3 H2O

- In base: Al2O3 + 2 NaOH + 3 H2O → 2 Na[Al(OH)4] (hydrated sodium aluminate)

Stannous oxide (SnO)

- In acid : SnO +2 HCl ⇌ SnCl2 + H2O

- In base : SnO +4 NaOH + H2O ⇌ Na4[Sn(OH)6]

Some other elements which form amphoteric oxides are gallium, indium, scandium, titanium, zirconium, vanadium, chromium, iron, cobalt, copper, silver, gold, germanium, antimony, bismuth, beryllium and tellurium.

Hydroxides

Aluminium hydroxide is also amphoteric:

- As a base (neutralizing an acid): Al(OH)3 + 3 HCl → AlCl3 + 3 H2O

- As an acid (neutralizing a base): Al(OH)3 + NaOH → Na[Al(OH)4]

- with acid: Be(OH)2 + 2 HCl → BeCl2 + 2 H2O

- with base: Be(OH)2 + 2 NaOH → Na2[Be(OH)4].[6]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amphoteric oxides. |

References

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "amphoteric". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00306

- Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2004). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 173–4. ISBN 978-0-13-039913-7.

- Penguin Science Dictionary 1994, Penguin Books

- Petrucci, Ralph H.; Harwood, William S.; Herring, F. Geoffrey (2002). General chemistry: principles and modern applications (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J: Prentice Hall. p. 669. ISBN 978-0-13-014329-7. LCCN 2001032331. OCLC 46872308.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skoog, Douglas A.; West, Donald M.; Holler, F. James; Crouch, Stanley R. (2014). Fundamentals of analytical chemistry (Ninth ed.). Belmont, CA. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-495-55828-6. OCLC 824171785.

- CHEMIX School & Lab - Software for Chemistry Learning, by Arne Standnes (program download required)