Bicarbonate

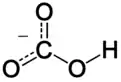

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogen carbonate[2]) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula HCO−

3.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Systematic IUPAC name

Hydroxidodioxidocarbonate(1−)[1] | |

| Other names

Hydrogencarbonate[1] | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 3DMet | |

| 3903504 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| 49249 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| HCO− 3 | |

| Molar mass | 61.0168 g mol−1 |

| log P | −0.82 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.3 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 7.7 |

| Conjugate acid | Carbonic acid |

| Conjugate base | Carbonate |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Bicarbonate serves a crucial biochemical role in the physiological pH buffering system.[3]

The term "bicarbonate" was coined in 1814 by the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston.[4] The prefix "bi" in "bicarbonate" comes from an outdated naming system and is based on the observation that there is twice as much carbonate (CO2−

3) per sodium ion in sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) and other bicarbonates than in sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) and other carbonates.[5] The name lives on as a trivial name.

According to the Wikipedia article IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry, the prefix bi– is a deprecated way of indicating the presence of a single hydrogen ion. The recommended nomenclature today mandates explicit referencing of the presence of the single hydrogen ion: sodium hydrogen carbonate or sodium carbonate. A parallel example is sodium bisulfite (NaHSO3).

Chemical properties

The bicarbonate ion (hydrogencarbonate ion) is an anion with the empirical formula HCO−

3 and a molecular mass of 61.01 daltons; it consists of one central carbon atom surrounded by three oxygen atoms in a trigonal planar arrangement, with a hydrogen atom attached to one of the oxygens. It is isoelectronic with nitric acid HNO

3. The bicarbonate ion carries a negative one formal charge and is an amphiprotic species which has both acidic and basic properties. It is both the conjugate base of carbonic acid H

2CO

3; and the conjugate acid of CO2−

3, the carbonate ion, as shown by these equilibrium reactions:

- CO2−

3 + 2 H2O ⇌ HCO−

3 + H2O + OH− ⇌ H2CO3 + 2 OH−

- H2CO3 + 2 H2O ⇌ HCO−

3 + H3O+ + H2O ⇌ CO2−

3 + 2 H3O+.

A bicarbonate salt forms when a positively charged ion attaches to the negatively charged oxygen atoms of the ion, forming an ionic compound. Many bicarbonates are soluble in water at standard temperature and pressure; in particular, sodium bicarbonate contributes to total dissolved solids, a common parameter for assessing water quality.

Physiological role

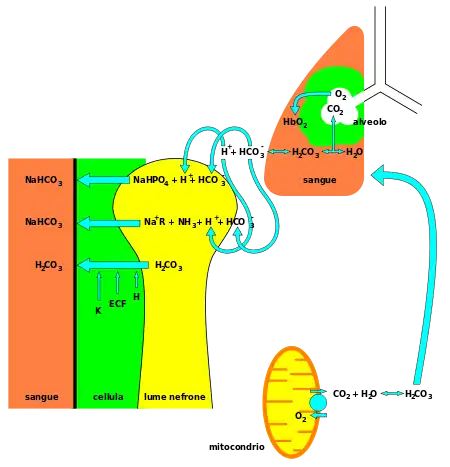

Bicarbonate (HCO−

3) is a vital component of the pH buffering system[3] of the human body (maintaining acid–base homeostasis). 70%–75% of CO2 in the body is converted into carbonic acid (H2CO3), which is the conjugate acid of HCO−

3 and can quickly turn into it.

With carbonic acid as the central intermediate species, bicarbonate – in conjunction with water, hydrogen ions, and carbon dioxide – forms this buffering system, which is maintained at the volatile equilibrium[3] required to provide prompt resistance to pH changes in both the acidic and basic directions. This is especially important for protecting tissues of the central nervous system, where pH changes too far outside of the normal range in either direction could prove disastrous (see acidosis or alkalosis).

Bicarbonate also serves much in the digestive system. It raises the internal pH of the stomach, after highly acidic digestive juices have finished in their digestion of food. Bicarbonate also acts to regulate pH in the small intestine. It is released from the pancreas in response to the hormone secretin to neutralize the acidic chyme entering the duodenum from the stomach.[6]

Bicarbonate in the environment

Bicarbonate is the dominant form of dissolved inorganic carbon in sea water,[7] and in most fresh waters. As such it is an important sink in the carbon cycle.

In freshwater ecology, strong photosynthetic activity by freshwater plants in daylight releases gaseous oxygen into the water and at the same time produces bicarbonate ions. These shift the pH upward until in certain circumstances the degree of alkalinity can become toxic to some organisms or can make other chemical constituents such as ammonia toxic. In darkness, when no photosynthesis occurs, respiration processes release carbon dioxide, and no new bicarbonate ions are produced, resulting in a rapid fall in pH.

Other uses

The most common salt of the bicarbonate ion is sodium bicarbonate, NaHCO3, which is commonly known as baking soda. When heated or exposed to an acid such as acetic acid (vinegar), sodium bicarbonate releases carbon dioxide. This is used as a leavening agent in baking.

The flow of bicarbonate ions from rocks weathered by the carbonic acid in rainwater is an important part of the carbon cycle.

Ammonium bicarbonate is used in digestive biscuit manufacture.

Diagnostics

In diagnostic medicine, the blood value of bicarbonate is one of several indicators of the state of acid–base physiology in the body. It is measured, along with carbon dioxide, chloride, potassium, and sodium, to assess electrolyte levels in an electrolyte panel test (which has Current Procedural Terminology, CPT, code 80051).

The parameter standard bicarbonate concentration (SBCe) is the bicarbonate concentration in the blood at a PaCO2 of 40 mmHg (5.33 kPa), full oxygen saturation and 36 °C.[8]

Bicarbonate compounds

References

- "hydrogencarbonate (CHEBI:17544)". Chemical Entities of Biological Interest (ChEBI). UK: European Institute of Bioinformatics. IUPAC Names. Archived from the original on 2015-06-07.

- Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry IUPAC Recommendations 2005 (PDF), IUPAC, p. 137, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-18

- "Clinical correlates of pH levels: bicarbonate as a buffer". Biology.arizona.edu. October 2006. Archived from the original on 2015-05-31.

- William Hyde Wollaston (1814) "A synoptic scale of chemical equivalents," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 104: 1-22. On page 11, Wollaston coins the term "bicarbonate": "The next question that occurs relates to the composition of this crystallized carbonate of potash, which I am induced to call bi-carbonate of potash, for the purpose of marking more decidedly the distinction between this salt and that which is commonly called a subcarbonate, and in order to refer at once to the double dose of carbonic acid contained in it."

- "Baking Soda". Newton – Ask a Scientist. Argonne National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Berne & Levy, Principles of Physiology

- "The chemistry of ocean acidification : OCB-OA". www.whoi.edu. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. 24 September 2012. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- Acid Base Balance (page 3) Archived 2002-06-13 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Look up bicarbonate in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Bicarbonates at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)