André and Magda Trocmé

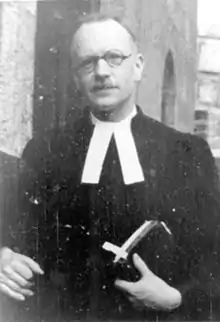

André Trocmé (April 7, 1901 – June 5, 1971) and his wife, Magda (née Grilli di Cortona, November 2, 1901 – October 10, 1996),[1] were a French couple designated Righteous Among the Nations. For 15 years, André served as a pastor in the French town of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, on the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon, in south-central France. He had been sent to the rather remote parish because of his pacifist positions, which were not well received by the French Protestant Church. In his preaching, he spoke out against discrimination as the Nazis were gaining power in neighbouring Germany and urged his Protestant Huguenot congregation to hide Jewish refugees from the Holocaust of the World War II.

Biography

André was born in Saint-Quentin-en-Tourmont. He married Magda, a native of Florence, in 1926. They had four children: Nelly, Jean-Pierre, Jacques, and Daniel.[1] In 1938, Pastor André Trocmé and the Reverend Edouard Theis founded the Collège Lycée International Cévenol in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. Its initial purpose was to prepare local country youngsters to enter the university. When the refugees arrived, it also took in many Jewish young people wishing to continue their secondary education.

When France fell to Nazi Germany, the mission to resist the Nazis became increasingly important. Believing in the same ideas as former Pastor Charles Guillon, André and Magda Trocmé became very involved in a wide network organizing the rescue of Jews fleeing the deportation efforts of the Nazi implementation of their Final Solution. Following the establishment of the Vichy France regime during the occupation, Trocmé and other area ministers serving other parishes encouraged their congregations to shelter "the people of the Bible" and for their cities to be a "city of refuge."[2] Trocmé was a catalyst whose efforts led to Le Chambon and surrounding villages becoming a unique haven in Nazi-occupied France. Trocmé and his church members helped their town develop ways of resisting the dominant force they faced. Together they established first one, and then a number of "safe houses" where Jewish and other refugees seeking to escape the Nazis could hide. These houses received contributions from the Quakers, the Salvation Army, the American Congregational Church, the pacifist movement Fellowship of Reconciliation, Jewish and Christian ecumenical groups, the French Protestant student organization Cimade and the Swiss Help to Children in order to house and buy food supplies for the fleeing refugees. Many refugees were helped to escape to Switzerland following an underground railroad network.

With the help of many dedicated people, families were located who were willing to accommodate Jewish refugees; members of the community reported to the railroad station to gather the arriving refugees, and the town's schools were prepared for the increased enrollment of new children, often under false names. Many village families and numerous farm families also took in children whose parents had been shipped to concentration camps in Germany. Trocmé refused to accept the definitions of those in power. "We do not know what a Jew is. We only know men", he said when asked by the Vichy authorities to produce a list of the Jews in the town.[3] Between 1940 and 1945 when World War II ended in Europe, it is estimated that about 3500 Jewish refugees including many children were saved by the small village of Le Chambon and the communities on the surrounding plateau because the people refused to give in to what they considered to be the illegitimate legal, military, and police power of the Nazis.

These activities eventually came to the attention of the anti-Jewish Vichy regime. Authorities and "security agents" were sent to perform searches within the town, most of which were unsuccessful. One arrest by the Gestapo led to the death of several young Jewish men in deportation camps. Their house director Daniel Trocmé, André's second cousin, refused to let the children put in his care be sent away without him; he was then arrested and later died in the Majdanek concentration camp. When Georges Lamirand, a minister in the Vichy government, made an official visit to Le Chambon on August 15, 1942, Trocmé expressed his opinions to him. Days later, the Vichy gendarmes were sent into the town to locate "illegal" aliens. Amidst rumors that Trocmé was soon to be arrested, he urged his parishioners to "do the will of God, not of men". He also spoke of the Biblical passage Deuteronomy 19:2–10, which speaks of the entitlement of the persecuted to shelter. The gendarmes were unsuccessful, and eventually left the town.

In February 1943, André Trocmé was arrested along with Edouard Theis and the public school headmaster Roger Darcissac. Sent to Saint-Paul d'Eyjeaux, an internment camp near Limoges, they were released after four weeks and pressed to sign a commitment to obey all government orders. Trocmé and Theis refused and were nevertheless released. They went underground where Trocmé was still able to keep the rescue and sanctuary efforts running smoothly with the help of many friends and collaborators.[4]

After the war, Trocmé served as European secretary for the International Fellowship of Reconciliation.[5] During the Algerian War, André and Magda set up the group Eirene in Morocco with the aid of the Mennonites, to help French conscientious objectors.[5]

André spent his final years as a pastor of a Reformed Church in Geneva, where he died. Magda died in Paris. André and Magda are buried in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon.[1]

Legacy

In January 1971, the Holocaust memorial center in Israel, Yad Vashem, recognized André Trocmé as Righteous among the Nations. He died later that year, Geneva.In July 1986, Magda was also recognized. Several years later, Yad Vashem honored the village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and the neighbouring communities with an engraved stele erected in its memorial park. It was the second time Yad Vashem honoured a whole community, the first time being the Dutch village of Nieuwlande in 1988.

André was the uncle of Daniel Trocmé (1910–1944), who was involved in similar activities to rescue Jews from the Vichy government and died in the Majdanek concentration camp in April 1944. In March 1976, Yad Vashem likewise recognized Daniel as Righteous among the Nations.[6]

Magda Trocmé was the guest of French radio program Les Chemins d'une Vie (Paths of a Life) recorded by Christian Lassalas for FR3 Auvergne Radio (April 1982 – 90 min).

The Plateau Vivarais-Lignon and Le Chambon-sur-Lignon became a symbol of the rescue of Jews in France during World War II.

As historians continue to examine events during the German occupation and Vichy rule, several longstanding disputes have emerged. In the case of the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon and Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, they include whether the interpretations based on Trocmé's writings are complete or correct but partial. Those issues are addressed in Robert Paxton's Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order (1972). Caroline Moorehead's Village of Secrets (2014) examine's both the events in the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon and Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and offers a review of conflicting interpretations.

See also

References

- "André Trocmé and Magda Trocmé Papers, 1919–date". Swarthmore College. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010.

- Atwood, Kathryn J. (2011). Women Heroes of World War II. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. p. 83. ISBN 9781556529610.

- Hallie 1979, p. 103.

- Pacifism in the Twentieth Century, by Peter Brock and Nigel Young. Syracuse University Press, New York, 1999 ISBN 0-8156-8125-9 (p. 220)

- Charles E. Moore, "Introduction" to André Trocmé Jesus and the Nonviolent Revolution. Orbis Books, 2004. ISBN 1570755388 (pp. ix–xvii).

- "The Village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon: André & Magda Trocmé, Daniel Trocmé". Righteous among the nations. 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- Volf & Bass 2001, p. 158.

- Hallie 1979, p. 85.

Citations

- Hallie, Philip P (1979), Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed: The Story of Le Chambon and How Goodness Happened There, New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 0-06-011701-X.

- Volf, Miroslav; Bass, Dorothy C. (2001), Practicing Theology: Beliefs and Practices in Christian Life, Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0-8028-4931-1.

External links

- The Chambon Foundation.

- Whosoever Saves a Single Life... (bibliography), Heart has reasons, archived from the original on 2013-10-26, retrieved 2006-01-01.

- Trocmé, André (2004) [Orbis Books, 1961], Moore, Charles E. (ed.), Jesus and the Nonviolent Revolution, Framington, PA: Plough Publishing.

- Sauvage, Pierre (1989). Weapons of the Spirit (Les armes de l'esprit). US/France: Chambon Foundation. Documentary. Aired in the US by the PBS.

- Trocmé, André, Yad Vashem.

- Best, Elizabeth Kirkley, Le Chambon, Shoah education.

- Pastor André Trocmé, The Jewish Foundation for the Righteous, archived from the original on 2011-07-23, retrieved 2008-06-20.

- "A French Town's Story", The New York Times.

- Trippett, Frank (May 21, 1979), "Good Neighbors", Time.

- André and Magda Trocmé, Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

- A Portrait of Pacifists: Le Chambon, the Holocaust, and the Lives of André and Magda Trocmé, Syracuse University Press, 2012.