The Holocaust in German-occupied Serbia

The Holocaust in German-occupied Serbia was part of the European-wide Holocaust, the Nazi genocide against Jews during World War II, which occurred in the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia, the military administration of the Third Reich established after the April 1941 invasion of Yugoslavia. The crimes were primarily committed by the German occupation authorities who implemented Nazi racial policies, assisted by the collaborationist forces of the successive puppet governments established by the Germans in the occupied territory.

.JPG.webp)

Immediately after the occupation, the occupation authorities introduced racial laws, labeling Jews and Romani as Untermensch ("sub-humans"). They also appointed two Serbian civil puppet governments to carry out administrative tasks in accordance with German direction and supervision.

Jews were the primary target but Romani were also targeted for elimination. The perpetrators of the Holocaust was the Nazi German Wehrmacht stationed in German-occupied Serbia. The main engine of extermination was the regular German army.[1][2] They carried out the operations with the assistance of the Milan Nedić's puppet government and Dimitrije Ljotić's fascist organization Yugoslav National Movement (Zbor). The murders were primarily carried out in concentration camps and gas vans. In May 1942, the occupied Serbia became one of the first territories declared judenfrei. The Nazis systematically murdered approximately 18,000 Serbian Jews in the occupied territory.

The main Holocaust perpetrators in Serbia convicted of war crimes were Nazi German officiers Harald Turner, August Meyszner and Johann Fortner. Milan Nedić was imprisoned, but committed suicide soon after, while Ljotić was killed in a car accident. As of 2019, 139 Serbians have been recognized as Righteous Among the Nations.

Background

Yugoslav Foreign Secretary Anton Korošec, who was Roman Catholic priest and leader of Slovenian conservatives, stated in September 1938, that "Jewish issue did not exist in Yugoslavia…. Jewish refugees from the Nazi Germany are not welcome here." In December 1938 Rabbi Isaac Alkalai, the only Jewish member of government was dismissed from the government.

On 25 March 1941, Prince Paul of Yugoslavia signed the Tripartite Pact, allying the Kingdom of Yugoslavia with the Axis powers. The Pact was extremely unpopular, particularly in Serbia and Montenegro, and demonstrations broke out. On 27 March, Serb military officers overthrew Prince Paul. The new government withdrew its support for the Axis, but did not repudiate the Tripartite Pact. Nevertheless, Axis forces, led by Nazi Germany invaded Yugoslavia in April 1941.

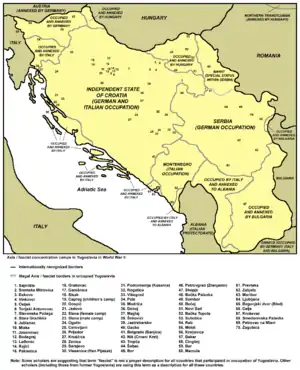

The Axis forces partitioned Serbia, with Hungary, Bulgaria, Italy and the Independent State of Croatia occupying and annexing large areas. In central Serbia the Germans occupiers established the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia (Gebiet des Militärbefehlshabers in Serbien), the only area of partitioned Yugoslavia under direct German military government, with the day-to-day administration of the territory controlled by the German Chief of the Military Administration. The German Military Commander in Serbia appointed a Serbian civil puppet government to carry out administrative tasks in accordance with German direction and supervision. The police and army of the puppet government were placed under German commanders.

In July 1941, a major uprising began in Serbia against the German occupiers, which included the establishment of the Republic of Užice, the first liberated territory in World War II Europe. At Hitler's personal command to crush the resistance, the German military started executing tens-of-thousands of Serb civilians, among whom they included thousands of Jews.[3] To assist in quelling the rebellion the German occupiers in August 1941 put in place the puppet government of Milan Nedić, which was also given responsibility for many Holocaust-related activities, including the registration and arrest of Jews and joint control over the Banjica concentration camp in Belgrade.[1]

The Holocaust

Anti-Semitic regulations

On 13 April 1941, before the Royal Yugoslav Army formally capitulated, Wilhelm Fuchs – Chief of the Einsatzgruppen based in Belgrade – ordered the registration of the city's Jews.[4] His order stated that all those who did not register would be shot.[5] Shortly after, Field Commander Colonel von Keisenberg issued a decree which limited their freedom of movement.[6] On 29 April 1941, the Chief of the German Military Administration in Serbia, Harald Turner issued the order to register all Jews and Gypsies throughout German-occupied Serbia. The order prescribed the wearing of yellow armbands, introduced forced labor and curfew, limited access to food and other provisions and banned the use of public transport.[7]

On 30 May, the German Military Commander in Serbia, Helmuth Förster, issued the main race laws - The Regulation Concerning Jews and Gypsies (Verordnung Betreffend Die Juden Und Zigeuner), which defined who is considered Jewish and Gypsy. The law excluded Jews and Roma from public and economic life, their property was seized, they were obliged to register in special lists (Judenregister and Zigeunerlisten) and for forced labor. In addition, the order prescribed the obligatory wearing of yellow tape for Jews and Roma, and prohibited them from working in public institutions or in professions such as law, medicine, dentistry, veterinary medicine and pharmacy, as well as visiting cinemas, theaters, entertainment venues, public baths, sports fields and markets.[5]

Beginning of persecution

Already in the initial days of the occupation, members of the German Einsatzgruppe Jugoslawien started breaking into and looting Jewish businesses.[8] Later these businesses were confiscated, per German anti-Semitic regulations, often turned over to the control of local Volksdeutsche.[8] All other Jewish real estate and personal property, plus religious properties, were also confiscated. A special form of theft was “the contribution”, amounting to 12 million dinars, which Belgrade Jews were forced to pay, for the “damages to Germans of the April War, which the Jews caused”.[8] In addition, the Germans forced Belgrade Jews to pay 1,400,000 dinars into a “Fund for the suppression of Jewish-Communist actions”.[8] Germans and Volksdeutsche mistreated and beat Jews on the streets, while in Belgrade Volksdeutsche and Ljotić-ites captured older Jews, bestially mistreating them.[9] Germans, with the help of Volksdeutsche and Ljotić-ites destroyed and desecrated Jewish temples.[10] The Germans conscripted all Jewish men between ages 14 and 60, and all Jewish women between 16 and 40, to perform forced labor for 17 and 18 hours a day, without rest. [11] They were forced to do the most difficult work, including remove with their bare hands the debris and bodies left from the extensive German bombardment of Belgrade.[12] Those who could not keep up, were shot by the German guards.

The killing of Jewish men

The destruction of Serbian Jews by the Nazi Germans was carried out in two distinct phases. The first, which lasted between July and November 1941, involved the murder of Jewish men, who were shot as part of retaliatory executions carried out by German forces in response to the rising anti-Nazi, partisan insurgency in Serbia. In October 1941. the German general, Franz Böhme, ordered the execution of 100 civilians for every German soldier killed and 50 for every wounded.[13] Böhme's order stated that hostages are to be drawn from "all Communists, people suspected of being Communists, all Jews, and a given number of nationalist and democratically minded inhabitants". Altogether some 30,000 Serbian civilians were executed by the Nazi's during the first 2 months of this policy,.[13] among them 5,000 Jewish men, or nearly all the Jewish males above age 14 in Serbia and the Banat.[14]

By the end of Summer 1941, the Gestapo and local Volksdeutsche had already rounded up all the Jews in the Banat and transferred them to the Topovske Šupe and Sajmište concentration camps.[15] The Germans carried out the first arrest of hostages in Belgrade in April 1941. From August to November 1941 Germans rounded up adult Jewish males from the rest of Serbia, and interred them at Topovske Šupe.[15] These formed the main reservoir of Jewish hostages to be shot as part of the German reprisal policy of executing Serbian civilians. From there the Germans took and executed the Jews at killing grounds at Jajinci, Jabuka (near Pančevo), etc,.[16] 500 Banat Jews were executed at Deliblatska peščara in the south Banat,[16] while some Jews were killed as part of mass German executions elsewhere, like the Kragujevac and Kraljevo massacres.[17] Thus, by the November of 1941 “there were almost no living male Jews who could be used as hostages.”[18]

The killing of women and children

The second genocidal activity, between December 1941 and May 1942, involved the incarceration of the women and children at the Semlin, or Sajmište concentration camp and their gassing in a mobile gas van called a Sauerwagen. The German concentration camp, in the old fairgrounds or Staro Sajmište, near Zemun was established across the Sava river from Belgrade, on the territory of the Independent State of Croatia, to process and eliminate the captured Jews, Serbs, Roma, and others.

On 8 December 1941, all remaining Belgrade Jews were ordered to report to the offices of the Judenreferat (Gestapo Jewish Police) in George Washington Street.[20] After handing over the keys to their homes, the Germans took them via the pontoon bridge over the Sava to the newly established Judenlager Semlin. 7,000 Jewish women and children were thus interred in the bombed-out camp fairgrounds over a brutal winter, when hundreds started to die.[20]

The first victims of the German gas van were the staff and patients at the two Jewish hospitals in Belgrade.[20] Over two days in March 1942, the Germans loaded over 800 people, mostly patients, into the gas van, in groups of between 80 and 100. They died of carbon-monoxide poisoning as the van drove to the killing grounds in Jajinci.[20] After the Jewish hospitals were emptied, the destruction of the Jewish women and children at Semlin began. As the historian Christopher Browning explains:

'Once loaded, the [gas van] drove to the Sava bridge just several hundred meters from the camp's entrance, where Andorfer [the camp commander] waited in the car so as not to have to witness the loading […] On the far side of the bridge, the gas van stopped and one of the drivers climbed out and worked underneath it, connecting the exhaust to the sealed compartment. The baggage truck turned off the road while the gas van and the commandant's car drove through the middle of Belgrade to reach a shooting range...ten kilometres south of the city.'.[20]

Between 19 March and 10 May, the drivers, Götz and Meyer, accompanied by the camp commander Herbert Andorfer, made between 65 and 70 trips between Semlin and Jajinci, killing 6,300 Jewish inmates.[20] Of the almost 7000 Jews interned at Semlin, fewer than 50 women survived. The victims of the camp included 10,600 Serbs and uncounted Romani . Gendarmes of Milan Nedić, Dimitrije Ljotić and Chetniks by September 1944 captured about 455 remaining Jews in Serbia who were handed over to the Banjica camp where they were immediately killed.[21][22]

The destruction of the Kladovo Transport

In December 1939, ships carrying about 1,200 Jewish refugees, mostly from Austria and Germany, landed in Kladovo, on Serbia’s border with Romania.[23] Fleeing the Nazis, they were travelling the Danube to the Black Sea to reach Palestine, but due to British limitations on Jewish emigration to Palestine, the Romanian authorities refused them passage. At first they lived onshore and aboard the ships at Kladovo, with aid provided by the Belgrade Jewish community. In September 1940, they were resettled to the Serbian town of Šabac, some moving into private homes, others living in community facilities. Welcomed by the Mayor and locals, they resumed cultural, educational and religious activities; some young men joined the city soccer team.[24] In April 1941, when the Germans invaded Serbia, they incarcerated Kladovo transport and local Jews in an internment camp near town. In September 1941, as part of retaliations for a Partisan attack on Šabac, the Germans took the Jewish men on a 46 kilometer, forced “bloody march”, during which they killed 21 stragglers.[24] In October 1941, Wehrmacht squads shot the rest of the Jewish men, as part of executions of 2,100 hostages in retaliation for 21 German soldiers killed by Partisans.[24] In January 1942 the Germans took the women and children to Zemun, then forced them to march 10 kilometers through the snow to the Sajmište concentration camp, with some infants dying along the way. With the exception of two Kladovo transport women who managed to survive, all were later murdered by the Germans via asphyxiation in gas vans, together with Jewish women and children from across Serbia.[24]

The Holocaust in the Banat

Local ethnic German Danube Swabian or Shwovish authorities in Banat helped carry out the Holocaust in that area of German-occupied Serbia. Approximately 4,000 to 10,000 Jews from the Banat were deported to the German military authorities in Serbia by the local ethnic German authorities under Sepp Janko to be killed in German concentration camps, including Sajmište and others.

Role of the Wehrmacht

Although the Wehrmacht, after the war, stated that it took no part in the genocidal programmes, General Böhme and his men planned and executed the slaughter of over 20,000 Jews and Gypsies without any signal from Berlin.[2] As Tomasevich notes:

The Germans carried out the Final Solution almost completely in Serbia and the Banat, even before this policy was formally announced. This was possible for two main reasons. First, Germany fully controlled these areas through occupation, and the destruction of the Jews could be carried out by German forces. Second the Communist-led resistance began in Serbia, and in the mass shootings of hostages in reprisal, the Germans included a large number of Jews held in concentration camps.[25]

A German soldier wrote after the war, 'the shooting of Jews bore no relation to the Partisan attacks': the retaliations merely provided 'an alibi for the extermination of the Jews'.[4] Chief of the Military Administration in Serbia, Harald Turner, justified the killing of Jews along Serb hostages, by practicality ('they [the Jews] are the ones we have in the camp' and 'the Jewish question solves itself most quickly in this way'), adding that '[the Jews] are also Serbian citizens and they have to disappear'.[4] By the time of the Wannsee Conference, the German military had already killed nearly all the Jewish men in Serbia and the Banat, and had herded the Jewish women and children into the Sajmiste concentration camp, in preparation for their extermination in the Spring of 1942.

The SS-commander Harald Turner, Chief of the German military administration in Serbia summed up how the Nazis carried out the genocide of Serbian Jews:

Already some months ago, I shot dead all the Jews I could get my hands on in this area, concentrated all the Jewish women and children in a camp and with the help of the SD (i.e. Sicherheitsdienst – Nazi Security Services) got my hands on a "delousing van," that in about 14 days to 4 weeks will have brought about the definitive clearing out of the camp...

— Dr. Harold Turner's letter to Karl Wolff, dated April 11, 1942.[26]

While the Germans were exclusively responsible for attempted extermination the Jews of Serbia proper, they were assisted by local collaborators in the Nedić government and others, who helped round up the Jews, Romani and Serbs who opposed the German occupation. Dimitrije Ljotić founded a Serbian pro-Nazi and pan-Serbian fascist party Zbor.[27][28][29][30] It was very active organization that published a large quantity of extreme anti-Semitic literature. The military wing of Zbor, the so-called Serbian Voluntary Guard actively supported the Gestapo in the elimination of Jews.

Emanuel Schäfer, commander of the Security Police and Gestapo in Serbia, convicted in Germany in 1953 for the death van killings of 6.000 Serbian Jews at Sajmiste, famously cabled Berlin after last Jews were killed in May 1942:

Similarly Harald Turner of the SS, later executed in Belgrade for his war crimes, stated in 1942 that:

Serbia is the only country in which the Jewish question and the Gypsy question has been solved.[32]

By the time Serbia and eastern parts of Yugoslavia were liberated in 1944, most of the Serbian Jewry had been murdered. Of the 82,500 Jews of Yugoslavia alive in 1941, only 14,000 (17%) survived the Holocaust.[33] Of the Serbian Jewish population of 16,000, the Nazis murdered approximately 14,500.[34][14][35]

Historian Christopher Browning who attended the conference on the subject of Holocaust and Serbian involvement stated:

Serbia was the only country outside Poland and the Soviet Union where all Jewish victims were killed on the spot without deportation, and was the first country after Estonia to be declared 'Judenfrei,'" a term used by the Nazis during the Holocaust to denote an area free of all Jews.

Collaborationist role

To assist in the fight against the growing Partisan-led resistance in Serbia, the German military set up an entirely subservient, collaborationist administration, with limited power.[37] While the Germans fully directed the Holocaust in Serbia, and carried out the mass-killing of Jews,[38][17] collaborationist forces assisted in a number of ways. At German command the quisling Special Police registered Jews, and enforced Nazi regulations, like wearing of yellow stars.[39] Later the German military performed mass round-ups of Jews to take them to concentration camps,[40][20] but relied on quisling forces to find and capture Jews who managed to elude the round-ups. Thus from 1942 to 1944 collaborationist forces captured and turned over at least 455 Jews to the Germans.[41] Some Jews who hid in the countryside were killed and robbed by Chetniks.[42]

The Germans and collaborationists jointly ran the Banjica concentration camp, where among the 23,697 recorded inmates, 688 were Jews.[43] The Gestapo killed 382 of these Jews in Banjica, taking the rest to other concentration camps.[43] Collaborationists, particularly members of the fascist Zbor, carried out anti-Semitic propaganda,[44] while Chetnik propaganda claimed that the Partisan resistance consisted of Jews.[45] Following the Nazi extermination of most Serbian Jews, a Nedić collaborationist document noted that "owing to the occupier, we have freed ourselves of Jews, and it is now up to us to rid ourselves of other immoral elements standing in the way of Serbia’s spiritual and national unity".[46]

The Germans placed the Banat region under the control of local, German-minority collaborationists.[17] These performed the first mass round-ups of Serbian Jews, sending local Jews to German concentration camps near Belgrade, where they were among the first to be killed by German forces.[17]

Number of victims

Of the Jewish population of 16,000 in German-occupied Serbia, the Nazis murdered approximately 14,500.[34] Citing Jasa Romano, Tomasevich notes that from Serbia Proper, the Germans killed 11,000 Jews, plus an additional 3,800 Jews from the German-minority-controlled, Banat region.[47]

According to Jelena Subotić, of the 33,500 Jews who lived in Serbia pre-occupation, around 27,000 were killed in the Holocaust. In German-occupied Serbia approximately 12,000 of the 17,000 Jews were killed very early into the war, including almost all 11,000 Belgrade Jews.[48]

According to Yugoslav experts and post-war reports by Yugoslav government commissions, almost all Jews from Serbia, including the Banat, appeared to have been killed. Those Jews who joined the Partisans survived as well as Jewish members of the Royal Yugoslav Army captured in the invasion who ended up in Germany as prisoners of war. This means that the number of murdered Jews is around 16,000 while Romano in his latest estimates reduced that number to 15,000 killed.[49]

German concentration camps in occupied Serbia

Help given by Serbian civilians

Miriam Steiner-Aviezer, a researcher into Yugoslavian Jewry and a member of Yad Vashem's Righteous Gentiles committee states: "The Serbs saved many Jews. Contrary to their present image in the world, the Serbs are friendly, loyal people who will not abandon their neighbors."[50] As of 2019, Yad Vashem recognizes 139 Serbians as Righteous Among the Nations. The numbers of Righteous are not necessarily an indication of the actual number of rescuers in each country, but reflect the cases that were made available to Yad Vashem.[51] Jaša Almuli, former president of the Jewish Association in Belgrade, wrote that the number of saved Jews was not higher because the occupying forces introduced the cruellest regime in Europe, besides the Soviet Union, which included the retaliation laws and prescribed executions.[52] Raphael Lemkin noted that Serbs were forbidden to help Jews by orders which provided the death penalty for sheltering or hiding Jews or accepting and buying objects of value from them.[53]

Restitution of properties

Serbia is the first country in Europe which adopted a law for restitution of properties of Jewish heirless victims of the Holocaust.[54] According to this law, besides this restitution, Serbia will make 950,000 EUR annual payment from its budget to the Union of Jewish Municipalities starting from 2017.[55] The World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO) praised the adoption of this law while its chair of operations invited other countries to follow Serbia's example. The Embassy of Israel in Serbia issued a release welcoming the adoption of this law and emphasizing that Serbia should be an example for other countries in Europe. The release of the Embassy of Israel concluded: "The new law is a noble act of a great country that will breathe new life into the small Jewish community that it is today."[56]

Revisionism in Serbia

During the 1990s, the role Nedić and Ljotić played in the extermination of Serbia's Jews was downplayed by several Serbian historians.[57] In 1993, the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts listed Nedić among The 100 most prominent Serbs.[58]

In 2006 a portrait of Milan Nedić was hung along with those of other Serbian heads of State in the Government of Serbia building. This and other attempts at rehabilitating Nedić met with sharp criticism, including from Aleksandar Lebl, head of the Association of Jewish Communities of Serbia who stated "Nedić was anti-Semitic, as were his government, police and armed forces – all these took part in the persecution of Jews, only the initiators and executors were German."[59] In 2009 Nedić’s portrait was removed after the initiative made by Ivica Dačić.[59]

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, local councillors in Smederevo campaigned to have the town's largest square named after Ljotić. The councillors defended Ljotić's wartime record and justified the initiative by stating that "[collaboration] ... is what the biological survival of the Serbian people demanded" during World War II.[60] Later, the Serbian magazine Pogledi published a series of articles attempting to exonerate Ljotić.[61] In 1996, future Yugoslav President Vojislav Koštunica praised Ljotić in a public statement.[62] Koštunica and his Democratic Party of Serbia (Demokratska stranka Srbije, DSS) actively campaigned to rehabilitate figures such as Ljotić and Nedić following the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević and his socialist government in October 2000.[62]

References

Notes

Footnotes

- Raphael Israeli (4 March 2013). The Death Camps of Croatia: Visions and Revisions, 1941–1945. Transaction Publishers. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4128-4930-2. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- Misha Glenny. The Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1804-1999. Page 502: "The Nazis were assisted by several thousand ethnic Germans as well as by supporters of Dijmitrje Ljotic's Yugoslav fascist movement, Zbor, and General Milan Nedic's quisling administration. But the main engine of extermination was the regular army. The destruction of the Serbian Jews gives the lie to Wehrmacht claims that it took no part in the genocidal programmes of the Nazis. Indeed, General Bohme and his men in German-occupied Serbia planned and carried out the murder of over 20,000 Jews and Gypsies without any prompting from Berlin"

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2002). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford University Press. p. 587. ISBN 978-0-8047-7924-1.

- "Semlin Judenlager". Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- "Poseta starom sajmistu". Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Manoschek, Walter (2000). National Socialist extermination policies: contemporary German perspectives and controversies. Oxford: Berghan Books. p. 164.

- Božović, Branislav (2004). Stradanje Jevreja u okupiranom Beogradu. Beograd: Srpska Školska Knjiga. pp. 282–283.

- Romano, p. 62.

- Romano, p. 65.

- Romano, p. 64.

- Romano, p. 67.

- Romano, p. 67-68.

- "Semlin Judenlager".

- Ristović, Milan (2010), "Jews in Serbia during World War Two" (PDF), Serbia. Righteous among Nations, Jewish Community of Zemun

- Ristovic, p. 12.

- Romano, p. 72.

- Tomasevich 2002, p. 585.

- Ristovic, p. 13.

- "Semlin Judenlager 1941-1942 - Semlin Judenlager - Open University". www.open.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- Byford.

- Haskin, Jeanne M. (2006). Bosnia and Beyond: The "quiet" Revolution that Wouldn't Go Quietly. Algora Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-87586-429-7.

- Philip J. Cohen, 1996, Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History, https://books.google.hr/books?id=Fz1PW_wnHYMC #page=83

- "Memorial to the Victims of the Kladovo Transport". Information portal to European sites of Remembrance.

- Lukic, Vesna (2018). The river Danube as a Holocaust landscape : journey of the Kladovo transport (Ph.D. thesis). University of Bristol.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2002). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford University Press. p. 585. ISBN 978-0-8047-7924-1.

- Visualizing Otherness II, Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, University of Minnesota.

- Skutsch, Carl (2005). Encyclopedia of the world's minorities, Volume 3. Routledge. p. 1083.

- Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2018). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, Volume III. Indiana University Press. p. 839.

- Newman, John (2015). Yugoslavia in the Shadow of War: Veterans and the Limits of State Building, 1903–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 248.

- Cohen, Phillip J. (1996). Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History. Texas A&M University Press. p. 37.

- Barry M. Lituchy (2006). Jasenovac and the Holocaust in Yugoslavia: analyses and survivor testimonies. Jasenovac Research Institute. p. xxxiii. ISBN 9780975343203.

- Dwork, Debórah; Robert Jan Pelt; Robert Jan Van Pelt (2003), Holocaust: a history, New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton & Company, p. 184, ISBN 0-393-32524-5

- Virtual Jewish History Tour – Serbia and Montenegro

- Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Macmillan Publishing Company New York 1990

- Lebel, G'eni (2007). Until "the Final Solution": The Jews in Belgrade 1521 - 1942. Avotaynu. p. 329. ISBN 9781886223332.

- Christopher Browning; Rachel Hirshfeld (29 May 2012). "Serbia WWII Death Camp to 'Multicultural' Development?". Arutz Sheva – Israel National News. israelnationalnews.com. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- Tomasevich 2002, p. 182.

- Israeli 2013, p. 31-32.

- Božović, Branislav. "Specijalna Policija I Stradanje Jevreja U Okupiranom Beogradu 1941-1944" (PDF).

- Ristovic, Milan. Jews in Serbia during World War Two. p. 12.

- Romano, Jasa. "Jevreji Jugoslavije 1941-1945, zrtve genocida i ucesnici NOR / Jasa Romano. p. 75. - Collections Search - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". collections.ushmm.org. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Lowenthal, Zdenko (1957). The Crimes of the Fascist Occupants and Their Collaborators Against Jews in Yugoslavia. Belgrade: Federation of Jewish Communities of the Federative People's Republic of Yugoslavia. p. 42.

- Israeli 2013, pp. 32–33.

- Byford 2011, p. 302.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). The Chetniks. Stanford University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

- Ristovic, p. 16.

- Tomasevich 2001, pp. 607.

- Subotić, Jelena (2019). Yellow Star, Red Star: Holocaust Remembrance after Communism. Cornell University Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1-50174-241-5.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford University Press. pp. 654–657. ISBN 978-0-80477-924-1.

- Derfner, Larry; Sedan, Gil (9 April 1999). "Why is Israel waffling on Kosovo". The Jewish News of Northern California.

- The Righteous Among The Nations Names and Numbers of Righteous Among the Nations – per Country & Ethnic Origin, as of 1 January 2019, Yad Vashem

- Almuli 2002, p. 78.

- Lemkin 2008, p. 250.

- Nikola Samardžić (10 December 2016). "Vraćanje imovine Jevrejima - Srbija lider u Evropi". N1. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

Srbija je prva država u Evropi koja je donela zakon o vraćanju imovine Jevreja ubijenih u Holokaustu koji nemaju naslednike. Profesor Filozofskog fakulteta Nikola Samardžić kaže da je suočavanje sa Holokaustom ozbiljno i da je Srbija lider u Evropi po ovom zakonu.

- Jelena Čalija (6 June 2016). "U avgustu prve odluke o vraćanju imovine stradalih Jevreja". Politika. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "Law passed on Jewish property seized during Holocaust". B92. Belgrade. 15 February 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- Perica 2002, p. 151.

- "Rehabilitacija Milana Nedića". BBC Serbian. 7 July 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Ko kači, a ko skida sliku Milana Nedića". Nedeljnik Vreme. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- Byford, Jovan (2011). "Willing Bystanders: Dimitrije Ljotić, "Shield Collaboration" and the Destruction of Serbia's Jews". In Haynes, Rebecca; Rady, Martyn (eds.). In the Shadow of Hitler: Personalities of the Right in Central and Eastern Europe. I.B.Tauris. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-84511-697-2.

- Macdonald, David Bruce (2002). Balkan Holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian Victim Centered Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia. Manchester University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-71906-467-8.

- Ramet 2005, p. 268.

Bibliography

- Almuli, Jaša (2002). Živi i mrtvi: razgovori sa Jevrejima. S. Mašić. ISBN 9788675980087.

- Hehn, Paul N. (1971). "Serbia, Croatia and Germany 1941–1945: Civil War and Revolution in the Balkans". Canadian Slavonic Papers. University of Alberta. 13 (4): 344–373. doi:10.1080/00085006.1971.11091249. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- Lemkin, Raphael (2008). Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. Clark, New Jersey: The Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 9781584779018.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: the History behind the Name. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-476-6.

- Perica, Vjekoslav (2002). Balkan idols: Religion and nationalism in Yugoslav states. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517429-8.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2005). Thinking about Yugoslavia: Scholarly Debates about the Yugoslav Breakup and the Wars in Bosnia and Kosovo. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61690-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Holocaust in Serbia. |