Ararat (film)

Ararat is a 2002 Canadian-French historical-drama film written and directed by Atom Egoyan and starring Charles Aznavour, Christopher Plummer, David Alpay, Arsinée Khanjian, Eric Bogosian, Bruce Greenwood and Elias Koteas. It is about a family and film crew in Toronto working on a film based loosely on the 1915 defense of Van during the Armenian Genocide. In addition to exploring the human impact of that specific historical event, Ararat examines the nature of truth and its representation through art. The Genocide is disputed by the Government of Turkey, an issue that partially inspired and is explored in the film.

| Ararat | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Atom Egoyan |

| Produced by | Atom Egoyan Robert Lantos |

| Written by | Atom Egoyan |

| Starring | Charles Aznavour Christopher Plummer David Alpay Arsinée Khanjian Eric Bogosian |

| Music by | Mychael Danna |

| Cinematography | Paul Sarossy |

| Edited by | Susan Shipton |

| Distributed by | Miramax Films |

Release date | |

Running time | 115 min. |

| Country | Canada France |

| Language | English Armenian French German |

| Budget | $15.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $2,743,336[1] |

The film was featured out of competition at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival. It won five awards at the 23rd Genie Awards, including Best Motion Picture.

Plot

In Toronto, an Armenian Canadian family is headed by Ani, a widow whose husband attempted to assassinate a Turkish ambassador. Her adult son Raffi is involved in a sexual affair with Celia, his step-sister, who has accused Ani of pushing her father off of a cliff, while Ani insists he slipped and fell. Ani gives art history presentations on Armenian American painter Arshile Gorky, with Celia constantly attending and publicly heckling Ani about concealing the truth.

An Armenian film director, Edward Saroyan, arrives to Toronto with a goal to make a film about the Armenian Genocide, the Van Resistance, and Gorky. Ani is hired as a historical consultant, with Raffi working on the project with his mother. An aspiring Turkish Canadian actor named Ali receives his big break when cast as Ottoman governor Jevdet Bey. Ali reads on the history of the genocide, which he had never heard much of before, and offends Raffi when he tells Saroyan that he believes the Ottomans felt the genocide was justified, in light of World War I. Raffi attempts to explain to Ali that the Armenians were citizens of the Ottoman Empire and that the Turks were not at war with them. Ali shrugs the encounter off, saying they were both born in Canada and they should together try to move past the genocide.

After Raffi returns to Canada from a flight to Turkey, he is interrogated at airport security by a retiring customs official named David, who has reason to believe Raffi is involved in a plot to smuggle drugs. Rather than employ drug-sniffing dogs, David prefers to speak to Raffi at length, with Raffi claiming he had taken it upon himself to shoot extra footage in Turkey. In fact, the film is premiering that night. Inspired by his own son, David chooses to believe Raffi is innocent, and releases him. The film reels remain with him, however, which David discovers to contain heroin.

Cast

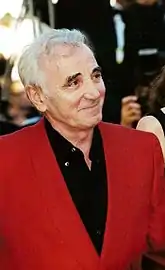

- Charles Aznavour as Edward Saroyan

- Christopher Plummer as David

- David Alpay as Raffi

- Arsinée Khanjian as Ani

- Eric Bogosian as Rouben

- Marie-Josée Croze as Celia

- Brent Carver as Philip

- Bruce Greenwood as Martin Harcourt, the actor playing Clarence Ussher

- Elias Koteas as Ali, the actor playing Jevdet Bey

- Lousnak as Shoushan, mother of Arshile Gorky

- Simon Abkarian as Arshile Gorky

- Garen Boyajian as young Arshile Gorky

Themes

.jpg.webp)

Issues explored in the film include truth and art. Using a story within a story device, the film explores whether films should recreate war crimes, and whether films can alter facts to communicate more important truths.[2]

Another theme of the film is gaps between generations, as it explores how later generations understand the historical record rather than the Armenian Genocide itself.[3] Numerous Armenian Canadian characters in the film identify symbols with their heritage, such as pictures of Mount Ararat. The fictionalized Arshile Gorky's symbols are a button and a photo of his mother.[3] Gorky is depicted in the film as a link between the history and current life of the Armenian people.[4]

Production

Development

Director Atom Egoyan and his wife, actress Arsinée Khanjian, are Armenian Canadians, and some of Egoyan's ancestors had been lost in the genocide. Egoyan had attempted to explain the genocide to their son, Arshile, when he was around six. Arshile asked, "Did the Turks say sorry?"[5] The film Ararat is intended as a response to that question.[6]

Producer Robert Lantos had promised that he would support a film about the genocide if Egoyan ever felt prepared to make one.[7] Alliance Films provided Egoyan a budget of $12 million.[8]

Filming

For cinematography, Egoyan worked with his frequent collaborator Paul Sarossy, with shooting taking place over 45 days during summer 2001. The battle scenes depicting the Defense of Van were shot in Drumheller, Alberta, with some of the soldiers actually being computer generated. The Van villages were also computer generated.[8]

Other scenes were shot at Cherry Beach in Toronto. The film could not be shot in Turkey or at the real Mount Ararat because of Turkey's denial of the genocide.[8]

The film was made prior to the Parliament of Canada voting to recognize the Armenian Genocide in 2004.[9] Egoyan said it was more important that the Turkish government accept the truth.[10]

Release

MGM considered distributing Ararat but Alex Yemenidjian, the chief executive, stated that financially it would not be rational for it to distribute the film; therefore Miramax distributed it instead.[11]

The film was screened out of competition at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival.[12] The film also played on the opening day of the 2002 Toronto International Film Festival on 5 September.[13] The film opened on 15 November 2002 in Los Angeles, New York City and Toronto.[7]

When Ararat was released, it was the sole film screened in commercial theaters in the United States in the modern era to be about the Armenian genocide.[11]

The Italian release of Ararat was intended to for 24 April 2003. However, its showing was unexpectedly banned by Italian authorities a day before the planned release, with the authorities explaining that the film's distributor missed the deadline to apply for a mandatory censorship certificate. The Embassy of Turkey in Rome acknowledged its government did not want the film screened in Italy, but said it was not involved in the decision that the film would not be shown.[14]

Initially Yılmaz Karakoyunlu, the Turkish Minister of State, said that the Turkish government would oppose the film as much as possible. However the Turkish government had given permission for the film to run in Turkey as it was, at the time, trying to increase freedom of expression so Turkey could join the European Union.[15] Belge Film had permission from the Turkish government to release the film in Turkey itself, but opted not to when nationalists pledged to "take action".[16] It ran on the Turkish TV station Kanaltürk four years later.[17]

Reception

Box office

In the opening week after the limited release on 15 November, the film averaged $35,188 per screen.[7] It made $162,000 in five theatres by 18 November.[18] By 24 days, it had made US$1.1 million in North America.[7]

The film completed its run on 30 January 2003, with a gross of $1,555,959 in North America. It grossed $1,187,377 in other territories for a total of $2,743,336.[1]

Critical reception

Critical reception was mostly negative.[19] In Canada, The Globe and Mail wrote "The metaphors are provocative, but too often, the viewer is left puzzled by the mechanics of the delivery."[7] Brian D. Johnson, writing for Maclean's, called it frustrating, though also interesting, and said it fell short despite ambition.[20] The National Post's review stated "Egoyan is almost crippled by a need to show all sides."[7] At the Toronto International Film Festival, the national panel of judges placed it in the year's top 10.[21]

Roger Ebert gave it two and a half stars, calling it "needlessly confusing," saying it "clearly comes from Egoyan's heart" but is "too much, too heavily layered, too needlessly difficult, too opaque." He also said it was disputed whether the film's quote from Adolf Hitler that the Armenian Genocide is forgotten is genuine.[6] In The New York Times, Stephen Holden called the film a "profound reflection on historical memory," and "hands down the year's most thought-provoking film."[22] The BBC's Tom Dawson wrote the film "feels clumsy and convoluted" compared to Egoyan's other work.[2] Ararat has a 55% rating at Rotten Tomatoes, based on 76 reviews,[23] and a metascore of 62 ("Generally favorable reviews") at Metacritic.[24]

Nationalist criticism

Ethnic Turks in Canada had proposed boycotting films by Disney and its subsidiary companies, and several nationalist critics sent e-mails to Egoyan and established websites arguing that the film's premise is not true.[15] Some individuals sent threats to Egoyan, including statements that a release of the film could result in danger for Armenians in Turkey.[25] Film Quarterly stated "Ararat touched off a new round of angry denials and charges of hate mongering."[15]

Accolades

The film won several awards. These included five awards at the 23rd Genie Awards, which Ararat star Arsinée Khanjian co-hosted with actor Peter Keleghan. Egoyan was not present.[26]

In 2008, the government of Israel also awarded the Dan David Prize to Egoyan for "creative rendering of the past." Ararat was especially a reason for the honour.[27]

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directors Guild of Canada | 4 October 2003 | Outstanding Direction - Feature Film | Atom Egoyan | Nominated | [28] |

| Outstanding Production Design - Long Form | Phillip Barker | Nominated | |||

| Outstanding Feature Film | Ararat | Nominated | |||

| Durban International Film Festival | 13–26 October 2003 | Best Film | Atom Egoyan | Won | [29] |

| Best Direction | Won | ||||

| Best Actress | Arsinée Khanjian | Won | |||

| Genie Awards | 13 February 2003 | Best Motion Picture | Robert Lantos and Atom Egoyan | Won | [26] |

| Best Actor | David Alpay | Nominated | |||

| Christopher Plummer | Nominated | ||||

| Best Actress | Arsinée Khanjian | Won | |||

| Best Supporting Actor | Elias Koteas | Won | |||

| Best Original Screenplay | Atom Egoyan | Nominated | |||

| Best Art Direction | Phillip Barker | Nominated | |||

| Best Costume Design | Beth Pasternak | Won | |||

| Best Score | Mychael Danna | Won | |||

| National Board of Review | 4 December 2002 | Freedom of Expression Award | Ararat | Won | [30] |

| Political Film Society | 2003 | Human Rights Award | Won | [31] | |

| Writers Guild of Canada | 14 April 2003 | Screenplay Award | Atom Egoyan | Won | [32] |

| Yerevan International Film Festival | 30 June-4 July 2004 | Best Film | Won | [29] | |

References

- "Ararat (2002)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Dawson, Tom (11 March 2003). "Ararat (2003)". BBC. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Siraganian 2016, p. 299.

- Mazierska 2011, p. 47.

- Bird, Maryann (20 April 2003). "Moving the Mountain". Time. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Ebert, Roger (22 November 2002). "Ararat". Rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Dillon, Mark (19 December 2002). "Ararat shines with nine". Playback. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Dillon, Mark (16 September 2002). "Egoyan, Sarossy think bigger on Ararat". Playback. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Hogikyan 2015, p. 39.

- Leung, Marlene (24 April 2015). "The political game: How one MP fought to have Canada recognize the Armenian Genocide". CTV News. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Welky, David (Spring 2006). "GLOBAL HOLLYWOOD VERSUS NATIONAL PRIDE: The Battle to Film The Forty Days of Musa Dagh". Film Quarterly. University of California Press. 59 (3): 35–43. doi:10.1525/fq.2006.59.3.35. JSTOR 10.1525/fq.2006.59.3.35. - Cited: p. 41

- "Festival de Cannes: Ararat". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- Dillon, Mark (8 July 2002). "Ararat to open TIFF2002". Playback. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Italy Bans Release of Atom Egoyan's Ararat". Asbarez. 28 April 2003. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- "Global Hollywood Versus National Pride: The Battle to Film The Forty Days of Musa Dagh". Film Quarterly. 1 March 2006. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- Koksal, Özlem (Fall 2014). "'Past Not-So-Perfect': Ararat and Its Reception in Turkey" (PDF). Cinema Journal. 54 (1): 46. doi:10.1353/cj.2014.0069.

- Koksal, Özlem (Fall 2014). "'Past Not-So-Perfect': Ararat and Its Reception in Turkey" (PDF). Cinema Journal. 54 (1): 47. doi:10.1353/cj.2014.0069.

- "Harry magical at box office". The Toronto Star. Associated Press. 18 November 2002. p. E04.

- Melnyk 2004, p. 161.

- Johnson, Brian D. (18 November 2002). "A MAZE OF DENIAL". Maclean's. Vol. 115 no. 46. p. 116.

- "Toronto International Film Festival 2002 Top Ten". Take One. March–May 2003. p. 50.

- Holden, Stephen (15 November 2002). "To Dwell on a Historic Tragedy or Not: A Bitter Choice". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Ararat (2002)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 12 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Ararat at Metacritic. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Buckley, Cara (20 April 2017). "Battle Over Two Films Represents Turkey's Quest to Control a Narrative". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

"The Promise", [...] was unfettered by studio pressures. The film’s financier was Kirk Kerkorian,

- McKay, John (14 February 2003). "Egoyan's Ararat named best film, takes 5 awards at the Genies". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Knelman, Martin (28 February 2008). "Egoyan recognized for Armenian perspective in Ararat". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Dinoff, Diston (18 August 2003). "Spider, Queer as Folk top DGC nominations". Playback. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Tschofen 2007, p. 370.

- "2002 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Hogikyan 2015, p. 38.

- "Canada's Writers Guild hands out awards". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

Bibliography

- Hogikyan, Nellie (2015). "Ararat". In Alan Whitehorn (ed.). The Armenian Genocide: The Essential Reference Guide. Santa Barbara, California and Denver: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610696883.

- Mazierska, Ewa (2011). European Cinema and Intertextuality: History, Memory and Politics. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230319547.

- Melnyk, George (2004). One Hundred Years of Canadian Cinema. Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802084443.

- Siraganian, Lisa (2016). "Hiding Horrors in Full View: Atom Egoyan's Representations of the Armenian Genocide". The Armenian Genocide Legacy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tschofen, Monique; Burwell, Jennifer, eds. (2007). Image and Territory: Essays on Atom Egoyan. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0889204874.