Autonomous Region of Bougainville

Bougainville (/ˈboʊɡənvɪl/ BOH-gən-vil;[3] Tok Pisin: Bogenvil[4][5]), officially the Autonomous Region of Bougainville,[6] is an autonomous region in Papua New Guinea. The largest island is Bougainville Island, while the region also includes Buka Island and a number of outlying islands and atolls. The interim capital is Buka, though it is expected that major government services and buildings will be moved to Arawa, following reconstruction.[7]

Autonomous Region of Bougainville | |

|---|---|

Motto: Peace, Unity, Prosperity | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital | Buka 6°0′S 155°0′E |

| Largest city | Arawa |

| Official languages | English, Tok Pisin |

| Other languages | Tok Pisin North Bougainville languages South Bougainville languages |

| Demonym(s) | Bougainvillean |

| Government | Autonomous Region |

| Ishmael Toroama | |

| Patrick Nisira | |

| Legislature | House of Representatives |

| Establishment | |

• Autonomy | 25 June 2002 |

| 7 December 2019 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 9,384 km2 (3,623 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2011 estimate | 249,358 |

| HDI (2018) | medium |

| Currency | Papua New Guinean kina (PGK) |

| Time zone | UTC+11 (Bougainville Standard Time) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +675 |

In 2011, the region had an estimated population of 250,000 people. The lingua franca of Bougainville is Tok Pisin, while a variety of Austronesian and non-Austronesian languages are also spoken. The region includes several Polynesian outliers where Polynesian languages are spoken. Geographically the islands of Bougainville and Buka are part of the Solomon Islands archipelago, but are politically separate from the independent country of Solomon Islands. Historically the region was known as the North Solomons.

Bougainville has been inhabited by humans for at least 29,000 years. During the colonial period the region was occupied and administered by the Germans, Australians, Japanese, and Americans for various periods. The name of the region originates from French admiral Louis Antoine de Bougainville,[8] who reached it in 1768.

Bougainvillean separatism dates to the 1960s, and the Republic of North Solomons was declared shortly before the independence of Papua New Guinea in 1975; it was subsumed into Papua New Guinea the following year. Conflict over the Panguna mine became the primary trigger for the Bougainville Civil War (1988–1998), which resulted in the deaths of up to 20,000 people. A peace agreement resulted in the creation of the Autonomous Bougainville Government.

In late 2019, a non-binding independence referendum was held with 98.31% voting for independence rather than continued autonomy within Papua New Guinea.

History

Prehistory

Bougainville has been inhabited by humans for at least 29,000 years, according to evidence obtained from Kilu Cave on Buka Island.[9] Until about 10,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum, there was a single island referred to as "Greater Bougainville" that spanned from the northern tip of Buka Island to the Nggela Islands north of Guadalcanal.[10]

The first inhabitants of Bougainville were Australo-Melanesians who presumably arrived from the Bismarck Archipelago.[11] Around 3,000 years ago, Austronesian peoples brought the Lapita culture to the islands,[12] introducing pottery, agriculture, and domesticated animals such as pigs, dogs, and chickens.[13] Both Austronesian and non-Austronesian languages are spoken on the islands to this day, however there has been significant mixing between the populations to the point that cultural and genetic differences are no longer correlated with language.[14]

Colonial history

The first Europeans to sight present-day Bougainville were the Dutch explorers Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire, who glimpsed Takuu Atoll and Nissan Island in 1616. British naval officer Philip Carteret saw Buka Island in 1767 and also visited what became the Carteret Islands. In 1768, French admiral Louis Antoine de Bougainville sailed along the east coast of the island that now bears his name.[12]

The German Empire, which had already begun operations in New Guinea, annexed present-day Bougainville in 1886, after agreeing with the United Kingdom to divide the Solomon Islands archipelago between them.[15] A German protectorate over the northern islands was established later that year, but the British Solomon Islands Protectorate was not established until 1893.[16] The initial boundary between the two territories was much more southerly, with Choiseul Island, Santa Isabel Island, Ontong Java, the Shortland Islands, and part of the Florida Islands included in the German section. The current boundary between PNG and Solomon Islands is derived from the Tripartite Convention of 1899, which saw those islands ceded to the United Kingdom.[17]

The German Solomon Islands were administered through German New Guinea, although it took almost two decades for an administrative presence to be established. The German administrative station at Kieta, established in 1905, was preceded by a Marist mission, which succeeded in converting a majority of the islanders to Catholicism.[18] The first fully commercial plantation was established in 1908, but German annexation had little economic impact.[19]

The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force occupied Bougainville in December 1914, as part of the Australian occupation of German New Guinea. The 1919 Treaty of Versailles established the former colony as a League of Nations mandate, administered by Australia as the Territory of New Guinea. A civilian administration was established in 1920, after which German nationals were deported and their property expropriated.[20] A number of punitive expeditions took place during both the German and Australian administrations, as part of "pacification" programs. The colonial period saw significant changes in the culture of the islanders.[21]

In 1942, Bougainville was invaded by the Japanese in order to provide a support base for the operations elsewhere in the South-West Pacific. The Allied counter-invasion resulted in heavy casualties, beginning in 1943, with full control of the islands not re-established until 1945. After the war the Australian government incorporated Bougainville and the rest of the mandate into the Territory of Papua and New Guinea, the immediate predecessor of present-day Papua New Guinea.

Modern history

Papua New Guinea gained its independence from Australia in 1975. As Bougainville is rich in copper and gold, a large mine had been established at Panguna in the early 1970s by Bougainville Copper Limited, a subsidiary of Rio Tinto. Disputes by regional residents with the company over adverse environmental impacts, failure to share financial benefits, and negative social changes brought by the mine resulted in a local revival for a secessionist movement that had been dormant. Activists proclaimed the independence of Bougainville (Republic of North Solomons) in 1975 and in 1990, but both times government forces suppressed the separatists.

Civil war

In 1988, the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA) increased their activity significantly. Prime Minister Sir Rabbie Namaliu ordered the Papua New Guinea Defense Force (PNGDF) to put down the rebellion, and the conflict escalated into a civil war. The PNGDF retreated from permanent positions on Bougainville in 1990, but continued military action. The conflict involved pro-independence and loyalist Bougainvillean groups as well as the PNGDF. The war claimed an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 lives.[22][23]

In 1996, Prime Minister Sir Julius Chan hired Sandline International, a private military company previously involved in supplying mercenaries in the civil war in Sierra Leone, to put down the rebellion. The Sandline affair was a controversial incident that resulted from use of these mercenary troops.

Peace agreement and autonomy

The Bougainville conflict ended in 1997, after negotiations brokered by New Zealand. A peace agreement was completed in 2000 and, together with disarmament, provided for the establishment of an Autonomous Bougainville Government. The parties agreed to have a referendum in the future on whether the island should become politically independent.[24]

On 25 July 2005 rebel leader Francis Ona died after a short illness. A former surveyor with Bougainville Copper, Ona was a key figure in the secessionist conflict and had refused to formally join the island's peace process.

In 2015 Australia announced it would establish a diplomatic post in Bougainville for the first time.[25] In 2016, it cancelled those plans acknowledging that it had not obtained the PNG government's approval.[26]

Geography

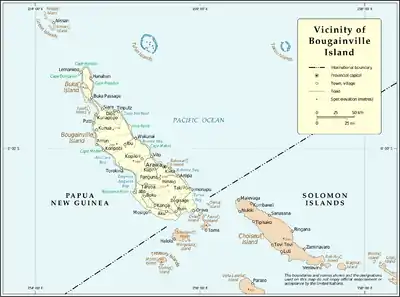

The Bougainville region occupies the north of the Solomon archipelago with Bougainville Island, which is the largest island of this group. The border between Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands lies just south in the middle of a 9 km strait that separates it from the Shortland Islands. The Solomon Island of Choiseul is 30 km further south.

The island of Buka is north of Bougainville, separated by a thin strait. The region includes other more or less remote islands and atolls:

- the Green Islands with its main island Nissan ;

- the Carteret Islands;

- Takuu Atoll;

- Nukumanu Atoll;

- the Nuguria Islands, a Polynesian exclave.

The territory constitutes an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean that has an area of 9384 square kilometers.

Government and politics

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Bougainville |

|

Elections for the first autonomous government were held in May and June 2005; Joseph Kabui, an independence leader, was elected President. He died in office on 6 June 2008. After interim elections to fill the remainder of his term, John Momis was elected as president in 2010 for a five-year term. He supports autonomy within a relationship with the national government of Papua New Guinea.

The Constitution of Bougainville specifies that the Autonomous Bougainville Government shall consist of three branches:[27]

- Executive: the President of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville who chairs the Bougainville Executive Council.

- Legislative: the Bougainville House of Representatives (39 elected members and two ex officio members).

- Judicial: the Bougainville Courts including a Supreme Court and High Court.

2019 independence referendum

President John Momis confirmed that Bougainville would hold a non-binding independence referendum in 2019.[28] The governments of both Bougainville and Papua New Guinea held a two-week referendum period which began on 23 November 2019 and closed on 7 December 2019, which is the final step in the Bougainville Peace Agreement.[29] The referendum question was a choice between greater autonomy within Papua New Guinea, or full independence. Over 98% of the valid ballots were cast for independence.[30][31]

Ishmael Toroama, a former rebel leader, was elected president of Bougainville on September 23, 2020.[32]

Districts and Local Level Government Areas

The region is divided into three districts, which are further divided into Local Level Government (LLGs) areas. For census purposes, the LLGAs are subdivided into wards, and those into census units.[33]

Demographics

Religion

The majority of people on Bougainville are Christian, an estimated 70% being Roman Catholic and a substantial minority being of the Protestant United Church of Papua New Guinea since 1968.

Languages

For general communication most Bougainvilleans use Tok Pisin as a lingua franca, and at least in the coastal areas Tok Pisin is often learned by children in a bilingual environment. Bougainville's constitution, written in English, does not specify an official language, but calls for constitutional literature to be translated into Tok Pisin and as many local languages as possible, while also encouraging the "development, preservation, and enrichment of all Bougainville languages".[34] There are many indigenous languages in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, belonging to three language families. None of the languages are spoken by more than 20% of the population, and the larger languages such as Nasioi, Korokoro Motuna, Telei, and Halia are split into dialects that are not always mutually intelligible.

The languages of the northern end of Bougainville Island, and some scattered around the coast, belong to the Austronesian family. The languages of the north-central and southern lobes of the island belong to the North and South Bougainville families. The most widely spoken Austronesian language is Halia and its dialects, spoken in the island of Buka and the Selau peninsula of Northern Bougainville. Other Austronesian languages include Nehan, Petats, Solos, Saposa (Taiof), Hahon and Tinputz, all spoken in the northern quarter of Bougainville, Buka and surrounding islands. These languages are closely related. Bannoni and Torau are Austronesian languages not closely related to the former, which are spoken in the coastal areas of central and south Bougainville. On the nearby Takuu Atoll a Polynesian language is spoken, Takuu.[35]

The Papuan languages are confined to the main island of Bougainville. These include Rotokas, a language with a very small inventory of phonemes, Eivo, Terei, Keriaka, Nasioi (Kieta), Nagovisi, Siwai (Motuna), Baitsi (sometimes considered a dialect of Siwai), Uisai and several others. These constitute two language families, North Bougainville and South Bougainville.

Economy

A small percentage of the region's economy is from mining. The majority of economic growth comes from agriculture and aquaculture. The region's biodiversity, which is one of the most important in Oceania, is heavily threatened by mining activities. Mining activities have caused civil unrest in the region many times. In January 2018, a moratorium on one mine was imposed by the Papua New Guinea government, in a bid to calm civil unrest against mining in the region.[36]

Culture

National symbols

A law passed by the provincial assembly – the Bougainville Flag, Emblem and Anthem (Protection) Act 2018 – affirmed the existing official status of the flag of Bougainville and emblem of Bougainville. Both the flag and emblem feature stylised depictions of the upe, a traditional headdress worn by men in parts of Bougainville to symbolise their transition to adulthood. The law also established "My Bougainville" as the region's anthem.[37][38]

Sport

Rugby league in Bougainville is administered by the Bougainville Rugby Football League (BRFL), which is affiliated with the Papua New Guinea Rugby Football League (PNGRFL).[39] A number of Bougainvilleans have played for the Papua New Guinea national rugby league team, including Bernard Wakatsi, Joe Katsi, Lauta Atoi, and Chris Siriosi.[40]

F.C. Bougainville has played in the National Soccer League since 2019, although it is based in Port Moresby rather than in Bougainville itself.[41] Previously, a team from Bougainville won the national soccer championships in 1977, defeating Rabaul.[42] Historically the Bougainville Soccer Association came into conflict with the Papua New Guinea Football Association over various matters.[43]

During the 1970s and 1980s, teams from Bougainville played against other regions in the PNG national championships for Australian rules football,[44] cricket,[45] and field hockey.[46]

Boxing is popular in Bougainville. The region won the 2017 National Boxing Championships, which were hosted in Arawa.[47] Notable boxers from the region include Commonwealth Boxing Council titleholder Johnny Aba and Pacific Games gold medalist Thadius Katua.[48]

Bougainvillean netball player Maleta Roberts has played professionally in Australia and represented the Papua New Guinea national netball team at the Commonwealth Games.[49]

See also

References

- "AUTONOMOUS REGION OF BOUGAINVILLE : Bougainville Flag, Emblem and Anthem (Protection) Bill 2018" (PDF). Abg.gov.pg. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- "Bougainville: a vote for independence". The World. ABC News. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "Bogenvil". Tok Pisin English Dictionary. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- "K20 milien bilong Bogenvil referendem". Loop PNG. 6 June 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- "The Constitution of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville" (PDF). abg.gov.pg/key-documents. Autonomous Bougainville Government. p. 28, S41.

- The Report: Papua New Guinea 2016. Oxford Business Group. 2016-09-19. ISBN 978-1-910068-64-9.

- Dunmore, John (2005-03-01). Storms and Dreams: Louis de Bougainville: Soldier, Navigator, Statesmen. Exisle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-77559-236-5.

- Spriggs, Matthew (2005). "Bougainville's early history: an archaeological perspective". In Regan, Anthony; Griffin, Helga-Maria (eds.). Bougainville Before the Conflict. Stranger Journalism. p. 1. ISBN 9781740761383.

- Spriggs 2005, pp. 2–4.

- Spriggs 2005, p. 5.

- Spriggs 2005, p. 18.

- Spriggs 2005, p. 9.

- Spriggs 2005, p. 19.

- Sack, Peter (2005). "German Colonial Rule in the Northern Solomons". In Regan, Anthony; Griffin, Helga-Maria (eds.). Bougainville Before the Conflict. Stranger Journalism. p. 77. ISBN 9781740761383.

- Griffin, James (2005). "Origins of Bougainville's Boundaries". In Regan, Anthony; Griffin, Helga-Maria (eds.). Bougainville Before the Conflict. Stranger Journalism. p. 74. ISBN 9781740761383.

- Griffin 2005, p. 75.

- Sack 2005, p. 84.

- Sack 2005, pp. 85–87.

- Elder, Peter (2005). "Between the Waitman's Wars: 1914–42". In Regan, Anthony; Griffin, Helga-Maria (eds.). Bougainville Before the Conflict. Stranger Journalism. p. 146. ISBN 9781740761383.

- Elder 2005, p. 150.

- Saovana-Spriggs, Ruth (2000). "Christianity and women in Bougainville" (PDF). Development Bulletin (51): 58–60. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-29. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- "EU Relations with Papua New Guinea". European Commission. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- Will Marshall, "Papua New Guinea government obtains shaky weapons disposal pact in Bougainville", World Socialist Web Site, May 23, 2001. Accessed on line March 4, 2008.

- Medhora, Shalailah. "Papua New Guinea not told of Australia's plans for new diplomatic post there". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- Canberra abandons Bougainville mission plan, Radio New Zealand, 8 May 2016

- "The Constitution of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville" (PDF). abg.gov.pg/key-documents. Autonomous Bougainville Government. p. 28, S41.

- "Bougainville confirms independence referendum before 2020 | Pacific Beat". Radioaustralia.net.au. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- "Ball rolling on Bougainville referendum". Radio New Zealand. 2016-05-22. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- AFP. "Bougainville voters back independence by landslide". The Standard. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Yeung, Jessie; Watson, Angus (11 December 2019). "Bougainville independence vote delivers emphatic demand to become world's newest nation". CNN. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Former rebel leader elected Bougainville president". www.aljazeera.com. Al Jazeera. September 23, 2020. Retrieved Sep 23, 2020.

- "Pacific Regional Statistics - Secretariat of the Pacific Community". Spc.int.

- Irwin, H. (1980). Takuu Dictionary. : A Polynesian language of the South Pacific. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. 428pp. ISBN 978-0858836372.

- Davidson, Helen (10 January 2018). "Bougainville imposes moratorium on Panguna mine over fears of civil unrest". the Guardian.

- "BOUGAINVILLE FLAG, EMBLEM AND ANTHEM (PROTECTION) ACT 2018" (PDF). Autonomous Bougainville Government. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "Bougainville Flag, Emblem and Anthem (Protection) Bill 2018: Explanatory Note" (PDF). Autonomous Bougainville Government. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "New Executives Set To Revive Rugby League". Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. 12 June 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "League Bilong Laif program commences in Bougainville". National Rugby League. 23 March 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "Sport: Bougainville to make PNG National Soccer League debut". Radio New Zealand. 24 January 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "A soccer lesson from Bougainville". Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. 14 April 1977.

- "Bougainville soccer issues a challenge". Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. 10 August 1973.

- "Rabaul too fit for Bougainville". Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. 21 May 1975.

- "Shield match in doubt". Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. 15 February 1980.

- "Hockey booming in Bougainville". Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. 27 April 1971.

- "Bougainville wins boxing title". The National. 18 September 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Belu, Simon. "Katua in Rio to chase Olympic dream". Bougainville. Archived from the original on 2016-08-25. Retrieved 2016-08-23.

- "Pride of a nation". Bendigo Advertiser. 27 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

Further reading

- Gillespie, Waratah Rosemarie (2009). Running with Rebels: Behind the Lies in Bougainville's hidden war. Australia: Ginibi Productions. ISBN 978-0-646-51047-7.

- Oliver, Douglas (1973). Bougainville: A Personal History. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Oliver, Douglas (1991). Black Islanders: A Personal Perspective of Bougainville, 1937–1991. Melbourne: Hyland House. Repeats text from previous 1973 reference and updates with summaries of Papua New Guinea press reports on the Bougainville Crisis.

- Pelton, Robert Young (2002). Hunter Hammer and Heaven, Journeys to Three World's Gone Mad. Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press. ISBN 1-58574-416-6.

- Quodling, Paul. Bougainville: The Mine and the People.

- Regan, Anthony; Griffin, Helga, eds. (2005). Bougainville Before the Crisis. Canberra: Pandanus Books.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Autonomous Region of Bougainville. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bougainville. |

- Autonomous Bougainville Government

- Autonomous Bougainville Government on Facebook

- Bougainville Inward Investment Bureau

- Full text of the Peace Agreement for Bougainville

- Constitution of Bougainville

- UN Map #4089—United Nations map of the vicinity of Bougainville Island in PDF

- Conciliation Resources—Bougainville Project

- The Coconut Revolution, a documentary film about the Bougainville Revolutionary Army.

- "Interview with Francis Ona" (1997)—Australian Broadcasting Corporation World in Focus; interview with Francis Ona. Interviewed by Wayne Coles-Janess.