Aviation Cadet Training Program (USN)

The US Navy had four programs (NavCad, NAP, AVMIDN, and MarCad) for the training of naval aviators.

Naval Aviator Program (1911–1917; 1917–1955; 1955–present)

In 1908 at Fort Myer, Virginia, a demonstration of an early "heavier-than-air" craft was flown by a pair of inventors named Orville and Wilbur Wright. Two navy officers observing the demonstration were inspired to push for the navy to acquire aircraft of their own. In May, 1911 the navy purchased their first aircraft. From 1911 to 1914 the navy received free flying lessons from aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss at North Island, San Diego, California.

In 1911, the navy began training its first pilots at the newly founded Aviation Camp at Annapolis, Maryland. In 1914, the navy opened Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida, dubbed the "Annapolis of the air", to train its first naval aviators. Candidates had to have served at least two years of sea duty and training was for 12 months. In 1917, the navy's program became part of the Flying Officer Training Program. Demand for pilots, however, still exceeded supply. The navy organized an unfunded naval militia in 1915 encouraging formation of ten state-run militia units of aviation enthusiasts. The Naval Appropriations Act of 29 August 1916 included funds for both a Naval Flying Corps (NFC) and a Naval Reserve Flying Corps. Students at several Ivy League colleges organized flying units and began pilot training at their own expenses. The NFC mustered 42 navy officers, six United States Marine Corps officers, and 239 enlisted men when the United States declared war on 6 April 1917. These men recruited and organized qualified members from the various state naval militia and college flying units into the Naval Reserve Flying Corps.[1]

Naval Aviation Cadet Program (1935–1968)

To meet the demand for aviators the Navy created a cadet program similar to the Flight Officer Program used by the Army.

Naval Aviation Cadet Act (1935)

On April 15, 1935, Congress passed the Naval Aviation Cadet Act. This set up the volunteer naval reserve class V-5 Naval Aviation Cadet (NavCad) program to send civilian and enlisted candidates to train as aviation cadets. Candidates had to be between the ages of 19 and 25, have an associate degree or at least two years of college, and had to complete a bachelor's degree within six years after graduation to keep their commission. Training was for 18 months and candidates had to agree to not marry during training and to serve for at least three more years of active duty service.[2]

Civilian candidates who had graduated or dropped out of college were classified as volunteer reserve class V-1 and held the rank of ordinary seaman in the organized reserve. Candidates who had not yet completed a four-year degree had a set time limit after training to complete it. Those that did not, lost their rank and received a transfer to volunteer reserve class V-6. Candidates who volunteered while still in college were enrolled in the Accredited College Program and were classified as volunteer reserve class V-1 (ACP).

Candidates who were not already in the navy were evaluated and processed at one of 13 naval reserve air bases across the country, each one representing one of the eligible naval districts. They consisted of the 1st and 3rd through 13th naval districts (representing the 48 states of the continental United States) and the 14th Naval District (comprising America's Pacific territories and headquartered at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii).

Candidates who were selected went on to Naval Flight Preparatory School. This was a course in physical training (to get the cadets in shape and weed out the unfit), military skills (marching, standing in formation, and performing the manual of arms), and naval customs and etiquette (as a naval officer was considered a gentleman). Pre-flight school was a refresher course in mathematics and physics with practical applications of these skills in flight. This was followed by a short preliminary flight training module in which the cadets did 10 hours in a simulator followed by a one-hour test flight with an instructor. Those that passed received V-5 flight badges (gold-metal aviator's wings with the V-5 badge set in the center). They were sent on to primary and basic flight training at NAS Pensacola and advanced flight training at another naval air station.

Graduates became naval aviators with the rank of aviation cadet, which was considered senior to the rank of chief petty officer but below the rank of warrant officer. As members of the volunteer reserve, they received the same pay as an ordinary seaman ($75 a month during training or duty ashore, $125 a month when on active sea duty, and $30 mess allowance). After three years of active service they were reviewed and could be promoted to the rank of lieutenant (junior grade) in the naval reserve and receive a $1,500 bonus.

Cadets who washed out of the V-5 program were assigned to volunteer reserve class V-6 with the rank of ordinary seaman.[3] This was a holding category that allowed the navy to evaluate the candidate for either reassignment to another part of the volunteer reserve or reassignment to the general service branches of the navy or naval reserve. They were exempt from being drafted by the army in wartime but were considered reservists in the navy and could be called to active service at any time.

Naval Aviation Reserve Act (1939)

Due to poor pay and slow promotion, many naval aviation cadets left the service to work for the growing commercial aviation and airline industries. On April 11, 1939, Congress passed the Naval Aviation Reserve Act, which expanded the parameters of the earlier Aviation Cadet Act. Training was for 12 months. Graduates received commissions in the Naval Reserve as an ensign or the Marine Corps Reserve as a 2nd lieutenant, and served an additional seven years on active duty.

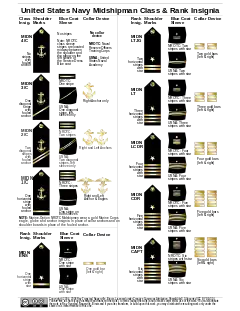

Uniforms and insignia

During basic and ground school their duty uniforms from 1935 to 1943 were green surplus Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) fatigue uniforms. Naval aviation cadets wore the same dress uniforms as naval officers once they completed primary.

Cadets wore a different insignia than army aviation cadets: a yellow shield with a blue chief with the word "navy" in yellow letters, a pair of naval aviator wings bordered and decorated in blue across the middle, and the letter-number "V-5" in blue in the base. The insignia was in enameled sterling silver for wear on the breast pocket of dress uniform jackets and cloth patch form for wear on uniforms. Graduates received gold-metal naval aviator's wings rather than the silver-metal wings awarded to army aviators.

1940–1945

During World War II, the USN pilot training program started to ramp up. It had the same stages as the army aviation program (pre-flight, primary, basic, and advanced), except basic flight added a carrier landing stage for fighter and torpedo- or dive-bomber pilots.

In 1940 it was modified to be more like the navy reserve's V-7 program. Candidates had to attend two 4-month semesters (or 10-week "quarters") of college before attending pre-flight. Pre-flight was divided into flight preparatory school, pre-Midshipman School, and Midshipman School. Flight Preparatory School was a four-week "boot camp" that taught discipline and drill, etiquette and protocol (as an officer was expected to be a gentleman), and ethics (as an officer was expected to be honorable); graduates became Seamen Second Class. Pre-Midshipman School was four months of accelerated academic coursework in science, math and physics for those candidates between the ages of 17 and 20 who did not have the educational requirements to attend Midshipman School; graduates became midshipmen. Midshipman School (nicknamed "Pre-Ensign") was three months of seamanship (swimming and boat-handling), navigation, ordnance, telegraphy, engineering, leadership, and naval military history; graduates became commissioned as Ensigns in the US Naval Reserve. Those that washed out were placed in the general V-6 pool as Seamen Second Class in the Naval Reserve.

In early 1943, flight preparatory schools were established at 17 colleges and universities.[4][5]

In July, 1943 the V-5 and V-7 programs were merged into the new V-12 program. V-5 students were reclassified as V-12A (with the A standing for Aviation). Candidates had to attend four 4-month semesters (or 10-week "quarters") of college before attending Pre-Flight or could opt to transfer to the NROTC. The V-12 program differed in that it was focused on college education and it eliminated the Naval Flight Preparatory School and War Training Services stages.[6][7]

Primary Flight School was at NAS Pensacola and it taught basic flying and landing. It used the NAF N3N or Stearman N2S Primary trainers, dubbed "Yellow Perils" from their bright yellow paintscheme (and the inexperience of the student pilots). Basic Flight School was broken into two parts: part one taught instrument flying and night flying and part two taught formation flying and gunnery; an additional part three stage for single-engined aircraft pilots taught carrier landing. They used the North American SNJ Basic trainer. Advanced Flight Training qualified the pilot on either a single-engined fighter, dive-bomber or torpedo bomber or a multiple-engined transport, patrol plane or bomber; graduates were classed as Naval Aviators and received gold Naval Aviator wings. Each graduate had around 600 total flight hours, with approximately 200 flight hours on front-line Navy aircraft. Pilots who washed out were assigned as regular ensigns.

Enlisted Naval Aviation cadets were paid $50 / month for the first month of training (as an Apprentice Seaman in "Boot Camp") and $75 / month for the second through eighth months (as a Seamen Second Class or midshipman attending training). Commissioned Naval Aviation students (NavCad Ensigns or commissioned officers attending Flight School) were paid $245 / month (the same pay as an ensign attending training).

In 1942 alone the program graduated 10,869 aviators, almost twice as many as had completed the program in the previous 8 years. In 1943 there were 20,842 graduates; in 1944, 21,067; and in 1945 there were 8,880. Thus in the period 1942 to 1945, the U.S. Navy produced 61,658 pilots – more than 2.5 times the number of pilots as the Imperial Japanese Navy.[8]

1946–1950

Under the Holloway Plan the NavCad Program was replaced with the seven-year Naval Aviation College Program (NACP). Candidates would attend college for two years as non-rated seamen. Then they would go to flight training as a midshipman and serve on active flight duty for a total of three years. After their first two years in rank as midshipmen they would be promoted to ensign. They would then get assigned stateside to finish up their college education for the final two years so they could keep their commission.

1950–1955

The NavCad program was restored in 1950 and existed until 1968. It was later restarted from 1986 to 1991.

1955–1968

The Navy program separated in 1955, forming the Aviation Officer Candidate School (AOCS) at NAS Pensacola. All Aviation Officer Candidates (AOCs) were 4 year college or university graduates instructed by Navy personnel and trained by Marine Corps Drill Instructors.

NavCads continued to be integrated into AOCS. The principal distinction was that AOCs, with their bachelor's degrees, were already commissioned as Ensigns in the Naval Reserve on graduation. They attended flight school as commissioned officers on par with their USNA, NROTC, Marine Corps OCS and PLC, USCGA and Coast Guard OCS classmates. In contrast, NavCads, who had some college, but typically lacked a bachelor's degree, attended their entire flight school program as non-commissioned candidates. They did not receive their commissions as Ensigns until they completed flight training and received their wings as Naval Aviators. These former NavCads, commissioned officers without bachelor's degrees, would complete their initial fleet squadron tour. They would then be sent to the Naval Postgraduate School or a civilian college or university as Ensigns on their first shore duty assignment in order to finish their baccalaureate degree. AOCS stopped taking NavCad civilian and enlisted candidates in 1966, thus ending the NavCad program for a time.

Single-engined pilots trained on the T-28 Trojan.[9] Pilot carrier landing training was performed on the USS Antietam[10] from 1957 to 1962 and the USS Lexington from 1962 to 1991. At NAS Memphis, they transitioned to the T2V SeaStar (1957-1970s) or T2 Buckeye (1959–2004) jet trainer.[11]

1968–1986

AOCS remained in operation with both the traditional AOCS pipeline for 4-year college and university and graduates, and the Aviation Reserve Officer Candidate (AVROC) pipeline which typically enrolled college and university students while they were college sophomores or juniors. AVROC students would then attend the first half of AOCS between their junior and senior year, returning for the second half of the program following their graduation and attainment of a BA or BS degree. For this reason, AVROC classes were clustered in the summer and fall months, typically interspersed between two traditional AOCS classes.

During this period, AOCS continued to produce prospective Naval Aviators, Naval Flight Officers (known as Naval Aviation Observers prior to 1966), and a smaller cohort of non-flying Air Intelligence Officers and Aircraft Maintenance Duty Officers. The length of the AOCS program was shortened by a few weeks in 1976 with the elimination of pre-commissioning training in the T-34B Mentor aircraft for Student Naval Aviators in the former Training Squadron ONE (VT-1) at the former NAS Saufley Field and a similar length pre-commissioning syllabus at Training Squadron TEN (VT-10) for Student Naval Flight Officers at NAS Pensacola / Sherman Field.

The AOCS program was all male until 1976 when the first female AOCs were inducted into the program.

1986–1993

NavCad was temporarily reopened in March 1986 to meet the demands of the expanding Navy of the Reagan presidential administration and was integrated back into the Aviation Officer Candidate School program. Candidates had to have either an associate degree or 60 semester hours of college study. Like their predecessors decades before, these NavCads would complete flight training as cadets, receive their commissions once they received their wings as Naval Aviators, and would later be afforded time to attend college to complete their degree on their first shore duty assignment. The NavCad program was shut down again following the end of the Cold War, a commensurate reduction in U.S. naval aviation force structure and a service personnel decision to return to limiting naval flight training to commissioned officer college graduates. The last civilian NavCad applicants were accepted in 1992 and the NavCad program finally canceled on October 1, 1993.

1994–Present

In 1994, the Navy's Officer Candidate School (OCS) program moved from the Naval Education and Training Command (NETC) at Naval Station Newport, Rhode Island to NAS Pensacola and was merged with AOCS. In July 2007, this merged OCS program relocated back to Newport. Today, prospective Naval Aviator, Naval Flight Officer, Naval Intelligence and Naval Aircraft Maintenance Duty officer candidates now attend the general OCS at NETC Newport. Following completion of the OCS program, graduates designated as Student Naval Aviators (SNA) and Student Naval Flight Officers (SNFO) proceed to Naval Aviation Schools Command at NAS Pensacola for Aviation Preflight Indoctrination with their SNA and SNFO counterparts commissioned via the U.S. Naval Academy, NROTC, Marine Corps Platoon Leaders Class-Air (PLC-Air), Marine Corps Officer Candidate Class, the U.S. Coast Guard Academy and Coast Guard OCS.

Naval Aviation Pilot (NAP) program (1916–1918; 1919–1940; 1941–1948)

This was a program to train Enlisted pilots in the Navy to fly large or multi-engined aircraft or pilot airships, since pilot officers were assigned to fly fighters and fighter/bombers.

1916–1917

A training program for enlisted pilots was begun on January 1, 1916, and consisted of seven Petty Officers and two Marine Sergeants. A second class was started on March 21, 1917, that consisted of nine Petty Officers (one of which was rolled over from the previous class).

1917–1918

Once the United States entered World War One, all pilot training at Pensacola was suspended. Naval Aviator candidates were sent to be trained in Europe after passing Ground School and the enlisted aviator program was suspended. Two hundred Landsmen (100 Quartermaster (Aviation) Landsmen and 100 Machinist (Aviation) Landsmen) were trained to act as ground crew.

To expand the number of available pilots, the US Navy sent 33 Quartermaster (Aviation) Petty Officers to pilot training schools in France and Italy. Graduates received military aviator's wings. Two Petty Officers (Harold H. "Kiddy" Karr and Clarence Woods) received both French and Italian pilot's wings. Thirteen became warrant officers or commissioned officers and twenty remained as petty officers. The enlisted aviators were used as Ferry Pilots. Ferry Pilots flew jury-rigged damaged planes to rear-area depots for extensive repairs that couldn't be done in the field. They would then fly repaired or new planes back to the forward airfields at the front.

1919–1940

After the war, the Navy decided that the dreary task of flying transport planes or dirigibles should fall to enlisted men. In 1921 the specialties were seaplane (scout aircraft with pontoon landing gear), ship-plane (scout aircraft designed to be catapulted from a ship), and airship (lighter-than-air craft).

1941–1948

During World War Two, the Navy, Coast Guard and Marine Corps produced Naval Aviation Pilots to meet the demands of the expanding Naval Aviation force.

The Navy produced 2,208 NAPs during the war and trained ? NAPs between 1945 and 1948. To meet the demand of the Korean War, 5 NAPs were created in 1950 before the program was closed.

The Coast Guard produced 179 NAPs during the war and later trained 37 NAPs between 1945 and 1948.

The Marine Corps produced 480 NAPs during the war.

1949–1981

After 1948, the NAP rating was officially ended. However, the NAPs were still in service, either reverting to their enlisted rank and position or continuing as pilots.

The last enlisted Marine Corps NAPs (Master Gunnery Sergeants Joseph A. Conroy, Leslie T. Ericson, Robert M. Lurie and Patrick J. O'Neil), simultaneously retired on February 1, 1973. The last Marine Corps NAP (Chief Warrant Officer 4 Henry "Bud" Wildfang) retired on May 31, 1978.

The last enlisted Coast Guard NAP (Master Chief Petty Officer/ADCMAP John P. Greathouse) retired in 1979.

The last enlisted Navy NAP (Master Chief Petty Officer/ACCM Robert K. "NAP" Jones) retired on January 31, 1981.

Aviation Midshipman (AvMIDN) Program (1946–1950)

Known as the "Holloway Plan", after its creator Rear Admiral James L. Holloway, Jr., the Naval Aviation College Program (NACP) was created by an act of Congress (Public Law 729) on August 13, 1946. It was designed to meet the perceived potential shortfall in Naval Aviators once the enlistments of the currently-serving veteran pre-war and wartime aviators expired.

The Naval Aviation College Program granted high school graduates between the ages of 17 and 24 a subsidized college education in a scientific or technical major for two years in exchange for enlistment as Apprentice Seaman (AS), USNR, and a commitment to serve in the navy for 5 years. Students received free tuition, fees and book costs and $50 per month for expenses. After completing pilot training within two years, they then had to serve on active duty for at least one year, for a total of three years. They then had to return to school to finish their remaining education within the remaining two years or lose their commission.

It also offered the remaining aviation cadets still in training and newly graduated Naval Aviators the chance to serve as full-time active duty pilots rather than be discharged or serve stateside and part-time in the Reserves. However, they would not receive the education benefits of the full aviation midshipmen, nor would they receive the starting rank of ensign like the aviation cadets. In January, 1947 the aviation cadet program was ended and only aviation midshipmen would be accepted for training.

The aviation midshipmen (dubbed "Holloway's Hooligans") had Regular Navy commissions rather than the Naval Reserve commissions granted the aviation cadets. However, they were not allowed to marry until they fulfilled their 3-year service commitment and could not be commissioned as ensigns until two years after their date of rank (the date they received their midshipman's warrant). They also had to live on meager pay ($132 a month; $88 base pay plus $44 Flight Status pay) while having to pay for mess fees and uniforms.

Later, the midshipmen were informed that their two years spent in training and active service as a pilot didn't count towards seniority, longevity pay or retirement benefits. This was not rectified until an Act of Congress was passed in 1974. Even then it only affected the less than 100 officers still in service.

Training (1946–1950)

After attending their first two years of school, the students attended around two years of pilot training. (Quick learners could qualify as Naval Aviators earlier than this and flew in fleet operational squadrons as aviation midshipmen). At the end of the two year appointment as aviation midshipmen, the newly designated Naval Aviators were commissioned as ensigns, USN.

First they attended a four-week Officer Candidate Training Course at NAS Pensacola. The students were drilled by navy petty officers. Graduates were promoted to aviation midshipmen fourth class and wore a khaki uniform with black dress shoes; they had no collar insignia badge. They were not allowed to drink and had restrictions on leave.

Pre-flight training was a refresher in math and science coursework and taught military skills like transmitting and receiving Morse Code. The candidates were drilled by Marine sergeants and were placed under a stricter regimen of discipline. Graduates of pre-flight were promoted to midshipmen third class; they wore a single gold fouled anchor badge on their right collar.

Primary Flight Training was at Whiting Field, where the midshipmen were taught basic flying. The wartime SNJ Texan (1935-1950s) primary trainer was used; it was later gradually replaced by the T-28 Trojan (used from 1950 to the early 1980s). Graduates were promoted to Midshipmen Second Class, who had gold fouled anchor badges on each collar.

Basic Flight Training was split into two parts. Flying by instruments and night flying were taught at Corry Field and formation flying and gunnery were taught at Saufley Field. Field Carrier Landing Practice (FCLP) was held at Barin Field. Carrier Qualification (CarQual) testing was first held aboard the USS Saipan (CVL-48) from September 1946 to April 1947; later it was held aboard the USS Wright (CVL-49) (1947 to 1952) or USS Cabot (CVL-28) (1948 to 1955). Graduates were promoted to Midshipmen First Class and got to wear gold fouled anchor badges with eagles perched on them on each collar. The student could now wear a Naval Aviator's green duty uniform and brown aviator's boots and restrictions on drinking and leaves were lifted.

Advanced Flight Training took place at NAS Corpus Christi, Texas. There the midshipmen were sorted into single-engine (fighters and fighter-bombers) and multiple-engine (transport, reconnaissance, and bomber) pilots. Although there were jet aircraft in service, Advanced training was on soon-to-be-obsolescent propeller driven aircraft like the F6F Hellcat (USS Saipan) and AD-4 Skyraider (USS Wright and USS Cabot).

Problems

From 1948 to 1950 the program was subject to cost-cutting due to post-war budget restructuring that favored the Air Force over the Navy. This impaired training and discouraged retention of its students and graduates. Midshipmen were being offered a release from their service commitment or a place in the Naval Reserve rather than a Regular Navy commission.

From June to September, 1948 the number of students at Pensacola expanded to five training battalions, swamping the facilities. Graduates of Pre-Flight in November and December 1948 were assigned to the USS Wright (CVL-49) to do maintenance and guard duty until a slot opened up for them at Whiting Field to begin Basic. In June, 1949 students in Basic and Advanced Flight Training were sent on leave for a month because Pensacola and Corpus Christi had used up their monthly aviation gasoline allotment and there was no funding for more.

On May 19, 1950, the Navy announced that the program was ending and that aviators would be drawn from Annapolis and Navy ROTC or OCS programs. Less than 40 members of the latest graduating class of 450 midshipmen would be retained and the rest (including the midshipmen still in training) would be let go by the end of June. The dawn of the Korean War on June 25 saved the remainder but they were told they were only authorized until July 31 (later extended to a 12-month period). In the fall of 1950 they were told that they could remain on active duty "indefinitely" (i.e., until the end of hostilities), but pre-war limits on promotion and pay would still be in force.

Dismissed Midshipmen were given a deal. They would be given enough free tuition, fees and book costs for two years to finish their college education; this deal would be revoked if they failed out. They also received a $100 cash stipend for expenses, twice what they received before.

Results

Around 3,600 students entered the program; an estimated 58% (around 2,100) of the aviation midshipmen graduated to become naval aviators.[12] The graduates went on to become extremely influential: fifteen became Admirals[13] and two (Neil Armstrong and Jim Lovell) became astronauts.[14]

Famous "Flying Midshipmen"

In 1946, Richard C. "Jake" Jacobi, one of the many aviation cadets who transferred to the program, became the first aviation midshipman to complete flight training.

Aviation Midshipman Joe Louis Akagi became the first Japanese-American Naval Aviator. He served in the Korean War with squadron VF-194 ("Red Lightning"). He received the Distinguished Flying Cross in June 1954.[15] for his valorous actions on July 26, 1953, in which he bombed a railroad tunnel, severed three railroad bridges, cut rail lines in two places, and knocked out two anti-aircraft positions.

In October 1948, Aviation Midshipman Jesse L. Brown was commissioned as an ensign and became the first African-American Naval Aviator. He served during the Korean War with VF-32 ("Fighting Swordsmen") flying the F4U Corsair, dying in combat on December 4, 1950. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.[16] The frigate USS Jesse L. Brown was named in his honor.

In May 1949, Norman Gerhart became the last aviation midshipman to complete the regular flight training program under the Holloway Plan.

On April 8, 1950, Ensign Thomas Lee Burgess of Patrol Squadron 26 (VP-26, the "Tridents"), became the first aviation midshipman to die while on active service. Burgess' PB4Y-2 Privateer, based at NAS Port Lyautey, Morocco, was shot down over the western Baltic Sea in international waters by the Soviet Air Force. The Soviets claimed they thought it was a B-29 bomber, that it had violated Latvian airspace, and that it had fired on planes sent to intercept it. No crewmen were recovered.

On August 16, 1950, Aviation Midshipman Neil Armstrong was qualified as a Naval Aviator; he was commissioned as an ensign in June 1951. He served during the Korean War with Fighter Squadron 51 (VF-51, the "Screaming Eagles"). He later became a NACA test pilot, a NASA astronaut, and was the first man to walk on the Moon on July 20, 1969.

Although he finished his education at United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Jim Lovell began as a midshipman cadet at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He flew F2H Banshee night fighters from 1954 to 1956 and qualified and taught transition flying in the McDonnell F3H Demon fighter in 1957. In 1958 he became a test pilot – later transitioning to being an astronaut. He was involved with Project Mercury and the Gemini and Apollo programs, was the command module pilot and navigator for the Apollo 8 mission and commanded the Apollo 13 mission. He was the first astronaut to travel in space four times and is one of only 24 men to orbit the moon. Afterwards he continued to serve in the US Navy, retiring at the rank of captain in 1973.

In 1982, Admiral George "Gus" Kinnear, the first Flying Midshipman to reach the rank of 4-star admiral, retired.

On August 1, 1984 Rear Admiral William A. Gureck, the last Regular Navy "Flying Midshipman", retired.

Marine Aviation Cadet (MarCad) program (1959–1968)

The Marine Corps developed programs to meet demand for pilots beginning in this time frame. Prior to this time, the Marine Corps simply relied on garnering its pilots from among Navy trainees. One hurdle was a three-year minimum service requirement after completing flight training, which caused hesitation among potential officer candidates. It was a five-year commitment because flight training was approximately two years.

In 1955, a special Platoon Leader's Course (PLC) variant called PLC (Aviation) was created. It was like PLC, but it sent officer candidates directly to the Navy's Aviation Officer Candidate School (AOCS) rather than Basic School. Its advantage was that if the candidate changed his mind, he could still go on to Basic. An Aviation Officer Candidate Course (AOCC) followed in 1963 to train dedicated Marine pilot officer candidates that went straight to AOCS.

Marine Cadet Program (MarCad)

Since this still did not meet the demand, the Marine Aviation Cadet (MarCad) program was created in July 1959 to take in enlisted Marines and civilian's with at least two years of college. Many but not all candidates attended "Boot Camp" and the School of Infantry before entering flight training. Early in the program flight training was deferred because the Naval Air Training Command at Pensacola did not yet have the capacity to absorb a growing number of trainees.[17] In the early 1960s the MarCad program expanded to meet the needs in Vietnam, while not lowering the bar to qualify as a Naval Aviator. All Navy pilot trainees, whether Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard, had to met the same standards to become a Naval Aviator. Likewise, MarCads were eligible for the same training pipelines as all other trainees: jets, multi-engine, or helicopters. With helicopter requirement looming large for Vietnam, MarCads shifted from flying the T-28C after carrier qualification to multi-engine training in the SNB (C-45), in which they obtained an instrument rating.[18] With few multi-engine billets in the Marine Corps, many MarCads transitioned to helicopters at Ellyson Field,[19] flying the Sikorsky H-34 (used 1960–1968)[20] or Bell TH-57A Sea Rangers (used 1968–1989)[21][http://www.helis.com/database/sqd/509/.

Graduates were designated Naval Aviators and commissioned 2nd Lieutenants in the Marine Corps Reserve. The MarCad program was closed to new applicants in 1967, the last trainee graduating in 1968. Most MarCads signed a contract to remain on active duty for three years after the completion of flight training in this time period. MarCads who did not complete flight training but had an active duty obligation remaining, would return to duty in the Marine Corps at a grade commensurate with their skills. Between 1959 and 1968 the program produced 1,296 Naval Aviators.

Famous MarCads

In February 1961 Second Lieutenant Clyde O. Childress USMC became the first MarCad to be commissioned. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross on July 18, 1966 for his valorous actions supporting Marine ground forces near Dong Ha, Vietnam during Operation Hastings. Childress retired in 1977 with the rank of Major.

On October 6, 1962, First Lieutenant Michael J. Tunney USMC not only became the first MarCad to die in combat, but did so in the first fatal Marine Corps helicopter crash in Vietnam. While serving with Marine Medium-Lift Helicopter Company HMM-163 ("Ridge Runners") in South Vietnam during Operation SHUFLY (Task Force 79.5), the UH-34D Seahorse helicopter Tunney was co-piloting crashed and burned due to mechanical failure. The badly-injured pilot, 1st Lieutenant William T. Sinnott USMC, was the only survivor. Sinnott had to be evacuated by helicopter through the thick jungle canopy. The body of door-gunner Sergeant Richard E. Hamilton USMC fell out during the crash and was found intact and otherwise unharmed. The burnt bodies of Flight Surgeon Lieutenant Gerald C. Griffin USN, Hospital Corpsman HM2 Gerald O. Norton USN,[22] and technicians Sergeant Jerald W. Pendell USMC and Lance Corporal Miguel A. Valentin USMC were recovered from the wreckage. The body of Crew Chief Corporal Thomas E. Anderson USMC was never found.[23]

On March 22, 1968, Second Lieutenant Larry D. "Moon" Mullins USMC was the last MarCad to be commissioned.

BGen Wayne T. Adams USMC (MarCad Class 14-62) was the highest-ranked MarCad, retiring with the rank of Brigadier-General in 1991. He was a fighter jet pilot (F8 Crusader) (), helicopter pilot (CH-46), and attack jet pilot (A-6 Intruder).

See also

References

- Mersky, Peter (1986). U.S. Naval Air Reserve. Washington, D.C.: Chief of Naval Operations. pp. 2–4.

- Mersky, Peter, ed. (1987). U.S. Naval Air Reserve. Washington, D.C.: Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (Air Warfare) and the Commander, Naval Air Systems Command. pp. 8–17. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ref/Ranks&Rates/index.html Ranks and Rates of the U.S. Navy - Together with Designations and Insignia

- Cardozier, V. R. (1993). Colleges and Universities in World War II. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. pp. 155–156. ISBN 9780275944322. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Supplemental Navy Department Appropriation Bill for 1943: Hearings Before the Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives, Seventy-eighth Congress, First Session, on the Supplemental Navy Department Appropriation Bill for 1943. Washington: United States Government Printing Office. 1943. pp. 260–261. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Herge, Henry C. (1948). Wartime College Training Programs of the Armed Services. American Council on Education. p. 62. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Herge, Henry C. (1996). Navy V-12. Paducah, Kentucky: Turner Publishing Company. p. 22. ISBN 9781563111891. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Grossnick, Roy A. (1997). "The History of Naval Aviator and Naval Aviation Pilot Designations and Numbers, The Training of Naval Aviators and the Number Trained (Designated)" (PDF). United States Naval Aviation, 1910-1995. Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center. p. 414. ISBN 0-945274-34-3. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- The Program

- The Program

- The Program

- Robert F. Dorr, (August 27, 2012) Neil Armstrong, Ejecting, and the Aviation Midshipmen, Defense Media Network.

- Robert F. Dorr, (August 27, 2012) Neil Armstrong, Ejecting, and the Aviation Midshipmen, Defense Media Network.

- Robert F. Dorr, (August 27, 2012) Neil Armstrong, Ejecting, and the Aviation Midshipmen, Defense Media Network.

- MilitaryTimes Hall of Valor - Distinguished Service Cross: Joe L. Akagi June, 1954

- MilitaryTimes Hall of Valor - Distinguished Service Cross: Jesse Leroy Brown December 4, 1950

- Fails, William R. (1978). Marines and Helicopters. Washington, DC: USMC.

- Sepulvado, Sr., Gary L. (December 14, 2018). Here We Go Again. Unpublished.

- NAS Ellyson Field

- Helicopter Training Unit One (HTU-1)

- Helicopter Training Squadron Eight (HT-8, "The Eightballers")

- Virtual Wall - Gerald Owen Norton: Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class Archived June 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Virtual Wall - Thomas Edward Anderson: Crew Chief

- Naval Aviation cadets

- Charles Glass. "NAVCAD Program Circa 53-54". Wings of Gold - The Journal of the Association of Naval Aviation, Summer 2005

- Marine Aviation cadets

- Lt.-Col. William R. Fails. Marines and Helicopters (1962–1973). Department of the Navy, History and Museums Division USMC, 1978.

- Jack Shulimson, Lt-Col. Leonard A. Blasiol USMC, Charles R. Smith, Capt. David A. Dawson USMC. U.S. Marines In Vietnam 1968: The Defining Year (Vol 9) Department of the Navy, History and Museums Division USMC, 1997. pp. 568–569

- Aviation midshipmen

- Paul C. Liebe, (Friday, June 22, 2007) Flying Midshipmen gather to recall early start as aviators Southern Maryland Newspapers Online.

- Robert F. Dorr, (August 27, 2012) Neil Armstrong, Ejecting, and the Aviation Midshipmen, Defense Media Network.

- Naval Aviation pilots

- Capt. Mark J. Campbell, USCG (November 1, 2003). "Enlisted Naval Aviation Pilots: A Legacy of Service". Naval Aviation News

Further reading

- Continuance of Navy V-12 College Training Program. 18 December 1945. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Navy V-12. Paducah, Kentucky: Turner Publishing. 1996. ISBN 9781563111891. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Navy V-12: Curricula Schedules, Course Descriptions; Bulletin No. 101. Training Division, Bureau of Naval Personnel, U.S. Navy. 1 November 1943. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Herge, Henry C. (1948). Wartime College Training Programs of the Armed Services. Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Rea, Robert R. (1987). Newton, Wesley Phillips (ed.). Wings of Gold: An Account of Naval Aviation Training in World War II. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780817358259. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Rominger, Donald W. (Winter 1985). "From Playing Field to Battleground: The United States Navy V-5 Preflight Program in World War II". Journal of Sport History. University of Illinois Press. 12 (3). S2CID 113121912. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- The Navy College Training Program V-12: Curricula Schedules, Course Descriptions. Training Division, Bureau of Naval Personnel, U.S. Navy. Retrieved 9 November 2020.