Axelrodichthys

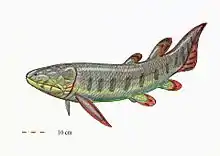

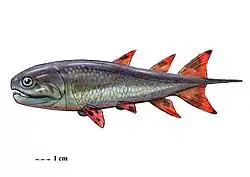

Axelrodichthys is an extinct genus of mawsoniid coelacanth from the Cretaceous of Africa, North and South America, and Europe. Several species are known, the remains of which were discovered in the Lower Cretaceous (Aptian-Albian) of Brazil,[1] North Africa,[2] and possibly Mexico,[3][4] as well as in the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco (Cenomanian),[5] Madagascar (Coniacian –Santonian)[2] and France (Lower Campanian to Lower Maastrichtian).[6][7] The French specimens are the last known representatives of the Mawsoniidae and the youngest of the extinct coelacanths along with the genus Megalocoelacanthus from North America.[7][8][9] The Axelrodichthys of the Lower Cretaceous frequented both brackish and coastal marine waters (lagoon-coastal environment) while the most recent species lived exclusively in fresh waters (lakes and rivers).[6][7] Most of the species of this genus reached 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) in length.[1] Axelrodichthys was named in 1986 by John G. Maisey in honor of the American ichthyologist Herbert R. Axelrod.[1]

| Axelrodichthys | |

|---|---|

| |

| Axelrodichthys araripensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Axelrodichthys Maisey, 1986 |

| Species | |

| |

Description

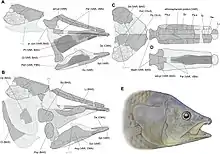

Like its close relative Mawsonia, Axelrodichthys is a coelacanth with an elongated, low, and wide skull, whose skull roof and cheek bones are characterized by strong ornamentation.[7] It differs from Mawsonia mainly in its more elongated parietonasal shield, the development of the descending process of the supratemporal, and by the shape and arrangement of the cheek and lower jaw bones. On the latter, the two posterior branches of the dentary are similar in length in Axelrodichthys while the lower branch of the bifurcation is much longer than the upper in Mawsonia. The contact area with the angular is also more extensive in Axelrodichthys.[10]

Taxonomy

Several species of Axelrodichthys have been described. The validity of some of them is discussed and other specimens are left in open nomenclature because represented by too incomplete specimens for specific determinations. The genus includes the following taxa:

- Axelrodichthys araripensis is the type species of the genus. It is also the best known species thanks to the discovery of numerous exceptionally preserved whole specimens in three dimensions in carbonate nodules.[1][10] These fossils come from the Crato Formation, Aptian in age, and especially from the Romualdo Formation, whose age is generally considered Albian but which could date from the late Aptian.[11] Both formations are located in the Araripe Basin in northeastern Brazil (Ceará, Pernambuco and Piauí states). It is possible that this species is also present in the Tlayúa Formation (late Albian) in the Puebla state in Mexico.[3] However, the specimen mentioned in the scientific literature has never been described and unfortunately was subsequently lost.[4]

- Axelrodichthys maiseyi comes from the mid-late Albian Codó Formation, located in the Grajaú Basin (Maranhão state) in northeastern Brazil. The species is named after John G. Maisey, the creator of the genus Axelrodichthys.[12] However, the status of A. maiseyi is discussed by some authors who doubt the interpretation of some anatomical structures and suggest revising this species.[10]

- Axelrodichthys megadromos comes from various Upper Cretaceous geological formations of southern France ranging in age from the Lower Campanian to the Lower Maastrichtian. The species is named after the Greek megas, large, and dromos, driveway, and refers both to the arrival in Europe of this gondwanan taxon, and to the construction of a new motorway near the type locality.[6] A. megadromos is represented by a partial skull and numerous isolated cranial bones from several sites of Provence (departments of Bouches-du-Rhône and Var) and Occitanie (Aude and Hérault).[7] The oldest specimens, including the holotype skull discovered at Ventabren in Bouches du Rhône, are Lower Campanian in age. The youngest specimen, from the Marnes Rouges Inférieures Formation in Aude, is magnetostratigraphically dated to the Lower Maastrichtian, 71.5 million years ago.[6][7][13] This species is therefore the last known representative of the Mawsoniidae and one of the youngest extinct coelacanths, along with the genus Megalocoelacanthus from North America of comparable age.[8][9] The presence of this species in what was the Ibero-Armorican island during the Late Cretaceous is an evidence of a dispersal event of the genus Axelrodichthys from western Gondwana (Africa + South America) to the European archipelago.[6][7]

- Axelrodichthys lavocati ?, named after the French paleontologist René Lavocat, has been found in the late Lower Cretaceous (Albian) and/or early Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian) sediments from Morocco and Algeria.[14][15][5] Known only from isolated bones, this species was first attributed to the genus Mawsonia[14][15] before being assigned to the genus Axelrodichthys in 2019.[10] The status of this species remains uncertain, however, as the material grouped under the name lavocati could in fact belong to both genera Mawsonia and Axelrodichthys.[16]

- Gottfried and colleagues have attributed to an indeterminate species of Axelrodichthys two isolated bones found in the Coniacian-Santonian Ankazomihaboka Formation (89.8 to 83.6 million years) of Madagascar.[2] The genus is also thought to be present in the Aptian of Niger.[2]

Paleoecology

Axelrodichthys lived in different environments depending the species and the time. During the Lower Cretaceous, the species A. araripensis inhabited both brackish and coastal marine waters of western Gondwana. Indeed, the Romualdo Formation, where this species mainly comes from, was deposited in a coastal lagoon influenced by cycles of marine transgressions and regressions and a variable supply of fresh water.[11] At the end of the Upper Cretaceous, the species A. megadromos lived exclusively in fresh water (lakes and rivers), on the Ibero-Armorican island, an unsular landmass made up of much of France and the Iberian peninsula.[6][7][17] All the sites that yielded this species show no marine influence. Lower Campanian specimens come from lacustrine deposits, and Upper Campanian and Lower Maastrichtian specimens were found in river and floodplain sediments.[18][6][7] The remains of Axelrodichthys from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco and Madagascar also come from freshwater sediments.[5][2] The arrival of the genus Axelrodichthys in the continental ecosystems of southwestern Europe probably occurred as a result of land connections that provided fluvial links between Europe and Gondwana.[17]

Little is known about the diet of mawsoniids. Although tiny teeth are present on the palate and the inner part of the mandible, the mouths of these fish are mostly toothless. As a result, some authors have speculated that they swallowed their preys using suction, such as the present-day Latimeria.[19] Other scientists have suggested that they may be filter feeders.[19] The description in 2018 of an articulated specimen of A. araripensis that swallowed a whole fish appears to confirm the suction technique.[20]

Phylogeny

A phylogenetic analysis of the mawsoniids published in 2020 found a polytomy grouping together the Cretaceous genera “Lualabaea”, Axelrodichthys, and Mawsonia, as well as the Jurassic marine genus Trachymetopon. The genus “Lualabaea” could be congeneric with Axelrodichthys.[7]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Maisey, J.G. (1986). "Coelacanths from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil". American Museum Novitates. 2866: 1–30.

- Gottfried, M.D.; Rogers, R.R.; Curry Rogers, K. (2004). "First record of Late Cretaceous coelacanths from Madagascar". In Arratia, G.; Wilson, M.H.; Cloutier, R. (eds.). Recent Advances in the Origin and Early Radiation of Vertebrates. München: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 687–691. ISBN 978-3-89937-052-2.

- Espinosa-Arrubarrena, L.; Applegate, S.P.; González-Rodríguez, K. (1996). "The first Mexican record of a coelacanth (Osteichthyes: Sarcopterygii) from the Tlayua quarries near Tepexi de Rodríguez, Puebla, with a discussion on the importance of this fossil: Sixth North American Paleontological Convention, Abstracts of Papers". Paleontological Society Special Publication. 116: 116. doi:10.1017/S2475262200001180.

- González-Rodríguez, K.A.; Fielitz, Ch.; Bravo-Cuevas, V.M.; Baños-Rodríguez, R.E. (2016). "Cretaceous osteichthyan fish assemblages from Mexico". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 71: 107–119.

- Cavin, L.; Boudad, L.; Tong, H.; Läng, E.; Tabouelle, J.; Vullo, R. (2015). "Taxonomic composition and trophic structure of the continental bony fish assemblage from the Early Late Cretaceous of Southeastern Morocco". PLoS ONE (10(5)): e0125786. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125786. PMC 4446216. PMID 26018561.

- Cavin, L.; Valentin, X.; Garcia, G. (2016). "A new mawsoniid coelacanth (Actinistia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Southern France". Cretaceous Research. 62: 65–73. doi:10.1016/.cretres.2016.02.002.

- Cavin, L.; Buffetaut, E.; Dutour, Y.; Garcia, G.; Le Loeuff, J.; Méchin, A.; Méchin, P.; Tong, H.; Tortosa, T.; Turini, E.; Valentin, X. (2020). "The last known freshwater coelacanths: New Late Cretaceous mawsoniids remains (Osteichthyes: Actinistia) from Southern France". PLoS ONE. 15(6): e0234183. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234183. PMC 7274394. PMID 32502171.

- Schwimmer, D.R.; Stewart, J.D.; Williams, G.D. (1994). "Giant fossil coelacanths of the Late Cretaceous in the eastern United States". Geology. 2(6): 503–506. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1994)022<0503:GFCOTL>2.3.CO;2.

- Dutel, H.; Maisey, J.P.; Schwimmer, D.R.; Janvier, P.; Herbin, M.; Clément, G. (2012). "Giant fossil coelacanths of the Late Cretaceous in the eastern United States". Geology. 10(5): e49911. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049911. PMID 23209614.

- Fragoso, L.G.C.; Brito, P.; Yabumoto, Y. (2019). "Axelrodichthys araripensis Maisey, 1986 revisited". Historical Biology. 31(10): 1350–1372. doi:10.1080/08912963.2018.1454443.

- Custódio, M.A.; Guaglio, F.; Warren, L.V.; Simões, M.G.; Fürsich, F.T.; Perinotto, J.A.; Assine, M.L. (2017). "The transgressive-regressive cycle of the Romualdo Formation (Araripe Basin): Sedimentary archive of the Early Cretaceous marine ingression in the interior of Northeast Brazil". Sedimentary Geology (359): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2017.07.010. hdl:11449/175030.

- de Carvalho, M.S.S.; Gallo, V.; Santos, H.R.S. (2013). "New species of coelacanth fish from the Lower Cretaceous (Albian) of the Grajaú Basin, NE Brazil". Cretaceous Research (46): 80–89. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2013.09.006.

- Fondevilla, V., Dinares-Turell, J., Vila, B., Le Loeuff, J., Estrada, R., Oms, O., and Galobart, A. (2016). "Magnetostratigraphy of the Maastrichtian continental record in the Upper Aude Valley (northern Pyrenees, France): Placing age constraints on the succession of dinosaur-bearing sites". Cretaceous Research. 57: 457–472. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.08.009.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Cavin, L.; Forey, P.L. (2004). "New mawsoniid coelacanth (Sarcopterygii: Actinistia) remains from the Cretaceous of the Kem Kem beds, SE Morocco". In Arratia, G.; Tintori, A. (eds.). Mesozoic Fishes III, Systematics, Palaeoenvironments and Biodiversity. München: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 493–506. ISBN 978-3-89937-053-9.

- Yabumoto, Y.; Uneyo, T. (2005). "New Materials of a Cretaceous Coelacanth, Mawsonia lavocati Tabaste from Morocco" (PDF). Bulletin of the Natural Science Museum, Tokyo, Series C. 31: 39–49.

- Cavin, L.; Cupello, C.; Yabumoto, Y.; Fragoso, L.G.C.; Deesri, U.; Brito, P.M. (2019). "Phylogeny and evolutionary history of mawsoniid coelacanths" (PDF). Bulletin of the Kitakyushu Museum of Natural History and Human History, Series A. 17: 3–13.

- Csiki-Sava, Z.; Buffetaut, E.; Ősi, A.; Pereda-Suberbiola, X.; Brusatte, S.L. (2015). "Island life in the Cretaceous-faunal composition, biostratigraphy, evolution, and extinction of land-living vertebrates on the Late Cretaceous European archipelago". ZooKeys (469): 1–161. doi:10.3897/zookeys.469.8439. PMC 4296572. PMID 25610343.

- Cavin, L.; Forey, P.L.; Tong, H.; Buffetaut, E. (2005). "Latest European coelacanth shows Gondwanan affinities". Biology Letters. 1(2): 176–177. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0287. PMC 1626220.

- Cavin, L. (2018). "Evolutionary Histories of Freshwater Fishes". In Cavin, L. (ed.). Freshwater Fishes: 250 Million Years of Evolutionary History. Croydon: Iste. pp. 69–75. ISBN 978-1785481383.

- Meunier, F.J.; Cupello, C.; Yabumoto, Y.; Brito, B.M. (2018). "The diet of the Early Cretaceous coelacanth Axelrodichthys araripensis Maisey, 1986 (Actinistia: Mawsoniidae)". Cybium. 42(1): 105–111. doi:10.26028/cybium/2018-421-011.

Further reading

- J. G. Maisey. 1986. Coelacanths from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil. American Museum Novitates 2866:1-30

- Discovering Fossil Fishes by John G. Maisey, David Miller, Ivy Rutzky, and Craig Chesek

- History of the Coelacanth Fishes by Peter Forey

- Living Fossil: The Story of the Coelacanth by Keith Stewart Thomson

- The Rise of Fishes: 500 Million Years of Evolution by John A. Long

.jpg.webp)