Béarn

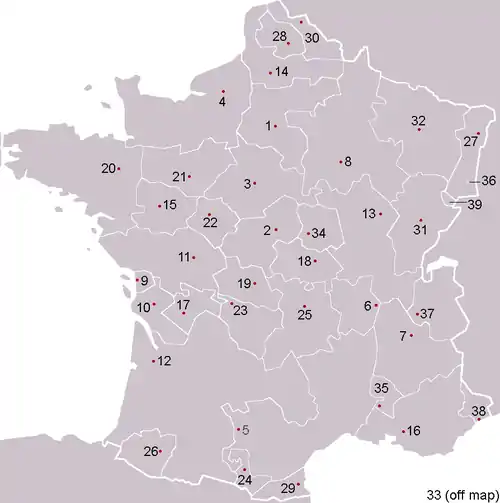

Béarn (US: /beɪˈɑːrn/;[1][2] French: [beaʁn]; Occitan: Bearn [beˈaɾ] or Biarn; Basque: Bearno or Biarno; Latin: Benearnia or Bearnia) is one of the traditional provinces of France, located in the Pyrenees mountains and in the plain at their feet, in southwest France. Along with the three Basque provinces of Soule, Lower Navarre, and Labourd, the principality of Bidache, as well as small parts of Gascony, it forms in the southwest the current département of Pyrénées-Atlantiques (64). The capitals of Béarn were Beneharnum (until 841), Morlaàs (from ca. 1100), Orthez (from the second half of the 13th century), and then Pau (beginning in the mid-15th century).[3]

Béarn Biarn Bearn | |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

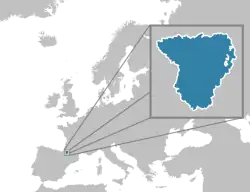

Béarn in Europe. | |

| Country | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

Béarn is bordered by Basque provinces Soule and Lower Navarre to the west, by Gascony (Landes and Armagnac) to the north, by Bigorre to the east, and by Spain (Aragon) to the south.

Today, the mainstays of the Béarn area are the petroleum industry, the aerospace industry through the helicopter turboshaft engine manufacturer Turbomeca, tourism and agriculture (much of which involves maize (corn) grown for seed). Pau was the birthplace of Elf Aquitaine, which has now become a part of the Total S.A. petroleum company.

In Alexandre Dumas's The Three Musketeers series, the protagonist d'Artagnan came from Béarn (he mentions having attended his father's funeral there in the second book, Twenty Years After). That d'Artagnan is usually referred to as a Gascon is neither surprising nor incorrect, as Béarn forms part of Gascony.

In the eastern part of the province are two small exclaves belonging to Bigorre. They are the result of how early Béarn grew to its traditional boundaries: some old lesser viscounties were added by marriage, and absorbed into Béarn: Oloron to the south/southwest ca. 1050, Montanérès in the east in 1085, and Dax in the west in 1194.[4] When Montanérès was added, five communities or parishes (Villenave-Près-Béarn, Escaunets, Séron, Gardères, and Luquet) did not form part of the dowry; they remained, or became, part of Bigorre. Their attachment to Bigorre continues to the present, as they followed it into Hautes-Pyrénées, rather than being incorporated into the surrounding Pyrénées-Atlantiques.

History

Etymology

The name Béarn derives from Beneharnum, the capital city of the ancient Venarni people, which was destroyed by Vikings by 840.[5] The modern town of Lescar is built on the site of Beneharnum.

Prehistory

Agriculture and metallurgy were first practiced in the region around 4,000 years ago. Many dolmens, tumuli and megaliths have been found in Béarn dating to this era, suggesting that ancestor worship was an important religious activity in neolithic Béarn.[6] Construction of cromlêhs in Béarn continued into the Bronze Age.

Fortified villages were also constructed in Neolithic Béarn, and remains of these have been found near Asson, Bougarber and Lacq.

Antiquity

Béarn was occupied by Ligurians around 3000 years ago. By 500 BC, Iberians appear to have replaced the Ligurians. The names of several towns in Béarn end in -os (e.g. Gelos, Urdos and Arros) which suggests an Iberian origin.

The region became part of the Roman Empire in the first century BC. Diocletian included Bearn in the Roman province of Novempopulania. Roman influence in the region waned in the fifth century AD, and Béarn experienced multiple barbarian invasions. Béarn was successively conquered by the Vandals, the Visigoths, the Merovingians and finally the Carolingians.

The fifth century AD also saw the arrival of Christianity in Béarn. The rural character of Béarn meant that Christianity took longer to become established there than elsewhere in France.

Transport

Road

Béarn is served by two autoroutes. The A64 (l'autoroute pyrénéenne, European designation E80) was built in 1977 and links Pau, Toulouse and Bayonne. In Béarn, the A64 has junctions serving the towns of Salies-de-Béarn, Orthez, Artix, Pau and Soumoulou.

The A65 (l'autoroute de Gascogne, European designation E7) links Pau with Langon. It serves the Béarnese towns of Lescar, Thèze and Garlin. At Langon, the A65 joins on to the A62, which continues to Bordeaux. The A65 was opened in 2010, and was at the time France's most expensive autoroute.

Several more minor routes also serve Béarn. The Route Nationale 134 links the south of Pau with Somport in the Aspe Valley. Several mountain roads link Somport with Spain.

Rail

Three railway lines serve Béarn. The first of these is the Toulouse to Bayonne railway, which was opened in stages between 1861 and 1867. Several rail stations are located on this line, including those of Coarraze-Nay, Assat, Pau, Artix, Orthez and Puyoô. The Puyoô to Dax railway line enables trains to run from Béarn to Bordeaux. Both these railway lines are served by TGV, Intercités and TER.

The third railway line, the Pau to Canfranc line, serves the south of Béarn. It was put into service between 1883 and 1928. However, the railway line been partially closed since 1970. This is because in 1970, a bridge carrying this rail line over the Gave d'Aspe was destroyed by a train derailment; SNCF consequently closed the line south of the Gare d'Oloron-Sainte-Marie. An additional section of the line, between Oloron-Sainte-Marie and Bedous, was reopened by SNCF in 2016.

Canfranc Railway Station is located within Spain and is also served by the Spanish Jaca to Canfranc railway. International rail transport between Béarn and Aragon was thus previously possible using this route. In 2013, the regional governments of Aragon and Aquitaine agreed to take steps to further the economic links between their two regions, including possibly reopening the Pau-Canfranc railway line all the way to Canfranc Station.[7] The two governments hope to have the line fully reopened by 2020.

A fourth railway line once linked Puyoô rail station to that of Mauléon-Licharre. This line opened in two stages between 1884 and 1887; it was closed to passengers in 1968 and to freight in 1989. The line was officially abandoned in 1991. A branch of this line ran from Autevielle to Saint-Palais. This branch is also now closed.

Aviation

Pau Pyrénées Airport, situated near Uzein, has direct flights to Charles de Gaulle Airport and Orly Airport (9 flights in total to Paris daily), Lyon–Saint-Exupéry Airport (3 flights daily) and Marseille Provence Airport. During summer, it also has flights to Bastia – Poretta Airport, Ajaccio Napoleon Bonaparte Airport, Naples International Airport and Bari Karol Wojtyła Airport. 634,000 passengers used Pau Pyrénées Airport in 2015, making it the third busiest airport in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine région of France, after Bordeaux–Mérignac Airport and Biarritz Pays Basque Airport.

Béarn has a long association with aviation. The meteorological conditions of Béarn were convenient for early aviators, and the Wright brothers made several flights in Pont-Long, a flat marshy area north of Pau from 1908 onwards. Wilbur Wright helped set up the world's first aviation school, which opened outside Pau in 1908. Pau Pyrénées Airport is located on the site of this aviation school. The French military trains its paratroopers at the School of Airborne Troops, which has been located near Pau since 1946.

People from Béarn

- Louis Barthou – Former politician

- François Bayrou – Candidate in the 2002, 2007 and 2012 French presidential elections, leader of the MoDem party, current mayor of Pau

- Charles Denis Bourbaki – A Bearnese French army officer of Greek origins, he distinguished himself during the Crimean war. The Bearnese football club FA Bourbaki Pau is named for him.

- The family of Alexander Gordon Bearn

- Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte – Marshal of France (1763–1844), Karl XIV Johan, King of Sweden and Norway (where he was known as Karl III Johan) from 1818 to 1844

- Gaston Phoebus – Gaston X of Bearn, Gaston III of Foix – Established Bearn's independence in 1347

- Gaston de Béarn – Gaston XI of Béarn, Gaston IV of Foix

- Mary, Viscountess of Béarn – (c. 1245 – c. 1319)

- Mary, Viscount of Béarn – (d. after 1187)

- Gaston Planté – French physicist who invented the lead acid battery in 1859

- Philippe Bernat-Salles – Former professional Rugby player

- Claude-François Bertrand de Boucheporn, last intendant of the Ancien Régime in Béarn (1785–1790)

- Henry IV of France – Ruled as King of France from 1589 to 1610

- Jean Bouilhou – Professional Rugby player

- Julian Bourdeu – Migrant to Argentina, he was devoted to cultural endeavours, being also a journalist and a Police Commissary

- Pierre Bourdieu – French sociologist

- Nicolas Brusque – Former professional rugby player

- Bertrand Cantat – Singer of the rock band Noir Désir

- Julien Cardy – Professional football player

- Jérémy Chardy – Professional tennis player

- Cataline, aka Jean Caux or Jean-Jacques Caux – Legendary packer during several gold rushes in British Columbia, Canada, is said to have been from Béarn (among other possibilities)

- Nicolas Escudé – Former professional tennis player

- Patrice Estanguet – Slalom canoeist

- Tony Estanguet – Famous slalom canoeist

- Jean de Forcade de Biaix (1663–1729) – a Huguenot and descendant of the noble family of Forcade, he became a Prussian Lieutenant General and confidant of King Frederick I of Prussia

- Pierre Jélyotte – Noted tenor of the Paris Opera

- Pierre Laclède – Co-founder of St. Louis, Missouri in 1764

- Jean de Laforcade, Seigneur de La Fitte-Juson – Attorney General, legislator, diplomat and descendant of the noble family of Forcade, he was described by 19th century genealogist, Bourrousse de Laffore as "…one of the most important men in Béarn…".[8]

- Jean-Michel Larqué – Professional football player

- Jean Lassalle – Politician, member of MoDem party executive office

- Jeanne III of Navarre – Queen regnant of Navarre from 1555 to 1572 and mother of King Henry IV of France

- Xavier Navarrot – Poet

- Robert Paparemborde – Professional rugby player

- Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte (1763–1844) – Maréchal de France, King of Sweden and Norway

- Jean-Baptiste Peyras-Loustalet – Professional rugby player

- Alejo Peyret – noted writer, agronomist, colonial administrator, and historian in Argentina after emigrating there at age 25

- Jean Saint-Josse – Politician

- Edouard Tinchant – politician born here, emigrated to the United States in 1862 and fought in the Civil War, elected as delegate to the 1867–1868 Louisiana constitutional convention, where he supported public rights for all, including civil and public rights for women[9]

- Damien Traille – Rugby player

- François de Béarn-Bonasse captain of the King,and lord of Saint-Dos (or Sendos) and Labastide-Villefranche.

See also

- Béarnaise sauce

- Béarnaise dance

- Béarnese dialect

- Béret

- Fors de Béarn

- Garbure

- Jambon de Bayonne

- Laruns – Laruns is a typical Bearnese village and commune

- Pau Pyrénées Airport

- Viscountcy of Béarn

- Viscounts of Béarn

- House of Bernadotte

References

- "Béarn". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- "Béarn". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- Bidot-Germa, Grosclaude, Duchon, Histoire de Béarn, 1986

- Bidot-Germa, Grosclaude, Duchon, Histoire de Béarn, 1986, p. 23

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History.

- Laborde, Jean Baptiste (1943). Le Béarn aux temps préhistoriques. p. 378.

- "PROTOCOLE D'ACCORD DU GOUVERNEMENT D'ARAGON ET DE LA RÉGION AQUITAINE SUR LA FEUILLE DE ROUTE 2012 – 2020 DE LA REPRISE DES CIRCULATIONS SUR LA LIGNE FERROVIAIRE PAU-CANFRANC-SARAGOSSE" (PDF).

- Bourrousse de Laffore (1860), Tome 3, p. 171

- Rebecca J. Scott and Jean M. Hébrard, Freedom Papers An Atlantic Odyssey in the Age of Emancipation, Harvard University Press, 2014

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Béarn. |

- Bearn in the History of Navarre

- (in English) Pau-Online.com