French Basque Country

The French Basque Country, or Northern Basque Country (Basque: Iparralde (lit. 'the Northern Region'), French: Pays basque français, Spanish: País Vasco francés) is a region lying on the west of the French department of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques. Since 1 January 2017, it constitutes the Basque Municipal Community (Basque: Euskal Hirigune Elkargoa; French: Communauté d'Agglomeration du Pays Basque) presided over by Jean-René Etchegaray.[1][2]

It includes three former historic French provinces in the north-east of the traditional Basque Country totalling 2,967 km2 (1,146 sq mi): Lower Navarre (French: Basse-Navarre; Basque: Nafarroa Beherea), until 1789 nominally Kingdom of Navarre, with 1,284 km2 (496 sq mi); Labourd (Lapurdi), with 800 km2 (310 sq mi); Soule (Zuberoa), with 785 km2 (303 sq mi). The population included in the Basque Municipal Community amounts to 309,723 inhabitants distributed in 158 municipalities.[3]

It is delimited in the north by the department of Landes, in the west by the Bay of Biscay, in the south by the Southern Basque Country and in the east by Béarn (although in the Béarnese village of Esquiule, Basque is spoken), which is the eastern part of the department. Bayonne and Biarritz (BAB) are its chief towns, included in the Basque Eurocity Bayonne-San Sebastián Euroregion.[4] It is a popular tourist destination and is somewhat distinct from neighbouring parts of either France or the southern Basque Country, since it was not industrialized as Biscay or Gipuzkoa and remained agricultural and a beach destination.

Territory

The department of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques is divided into three districts or arrondissements: The Arrondissement of Bayonne, the Arrondissement of Oloron-Sainte-Marie, and the Arrondissement of Pau. NorthernBasque Country includes all of Bayonne and Canton of Montagne Basque in Oloron-Sainte-Marie. Additionally, Northern Basque Country includes the following territories in Béarn: Esquiule, Aramits, Géronce, and Arette (in the Canton of Oloron-Sainte-Marie-1).

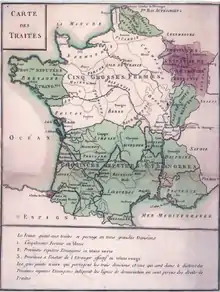

French Basque Country included three pre-existing historic territories before the departmental division of France in 1789, with a few modifications:

- Labourd (French: Labourd, Basque: Lapurdi and in Gascon: Labord). Bayonne is conventionally considered part of Labourd, but it stopped belonging to it in the 13th century. A few municipalities are considered a part of Lapurdi and are a part of the “Council of the Elected” and the “Council of the Development of the French Basque Country” but did not belong the historic region of Lapurdi. Among them are Boucau, which belonged to the department of Landes until 1857, Bardos, Guiche, and Urt (which was united administratively to Lapurdi in 1763 but seceded judicially from the Seneschal of Came (Bidache). Lapurdi is located within the Arrondissement of Bayonne.

- Lower Navarre (French: Basse-Navarre, Basque: Behe Nafarroa, Gascon: Baisha Navarra). Arancou, Came, and Sames belong to Lower Navarre and are a part of the Council of Elects and the Council of the Development of the French Basque Country. They were dependent on the Seneschal of Dax during the Ancien Régime, not dependent on Navarre. Bidache, a territory that was a sovereign principality during the Ancien Régime, did not belong to Navarre although it is also a part of the Council of Elects and the Council of the Development of the French Basque Country. On the other hand, Escos (a town in the Salies-de-Béarn canton) has usually not been considered a part of Lower Navarre, even though it belonged to Navarre during the Ancien Régime. Additionally, it has not entered the Councils of the French Basque Country. Lower Navarre is located within the Arrondissement of Bayonne.

- Soule (French: Soule, Basque: Zuberoa, and in Gascon: Sola). Esquiule (a Béarnese community during the Ancien Régime) is usually included on the list of Souletin populations, since its population is historically Basque-speaking. However, it became part of Béarn and has not requested admission into the Councils of the French Basque Country. Soule is divided between the districts of Bayonne and Oloron-Sainte-Marie, where the majority of its communes are located. These 35 Souletin communes of the Arondissement of Oloron-Sainte-Marie are a part of a Municipal Commonwealth, the Communauté de Communes de Soule-Xiberoa (in Souletin: Xiberoko Herri Alkargoa).

Cities

The most important city in the territory is Bayonne (French: Bayonne, in Gascon and Basque: Baiona). The ancient Lapurdum romana, from which the toponyms Labourd, Lapurdi or Labourd originate, is a part of the Biarrits-Anglet-Bayona agglomeration community (BAB) alongside Biarritz and Anglet (Basque: Angelu), the most populated urban space in the territory. It is the political capital of its subprefecture and economic capital of the largest region, which includes French Basque Country and he south of Landes. Other important places are Saint-Jean-de-Luz (Basque: Donibane Lohizune), Hendaye (Hendaia), Sainte-Jean-Pied-de-Port (Donibane Garazi), the capital of Lower Navarre, and Mauleón (Maule), the capital of Soule.

Proposed institutional reforms

A slow but continuous French institutional evolution has been produced as a response to the historical vindications of the French Basque Country. By an order from 29 January 1997 from the prefect of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques, a “Basque Country” was recognized as a pays, according to the French administrative category,[5] in accordance with the laws called: the Pasqua Law[6] from 4 February 1995, and the Voynet Law[7] from 25 June 1999. These are based on the notion of a country in the traditional sense, as a social belonging to a place, culture, etc., promoting the organization and development of the territory in a global manner.

The creation of an institution of greater substance than what was represented by the geographical organization of pays and more specifically of a Basque department, has been a constant element during that last decades in elected posts for the main political parties, with representation from the French Socialist Party, The Republicans, and nationalist parties.[8] 64% of Basque-French mayors [9] support such a creation. The Association des Élus[10] is an association that groups political posts such as regional councilors, general councilors and mayors of the French Basque Country, from both political spectrums, whose goal is to achieve the division of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department into Basque and Béarnese departments respectively.

The Council of the Development of the French Basque Country was created in 1994, and in 1995 the Council of the Elected of the French Basque Country (Association des Élus du Pays Basque) was created.

On 15 January 2005, the Euskal Herriko Laborantza Ganbara (Chamber of Agriculture for the Basque Country),[11] was created as a house for the representation and promotion of the interests of livestock farmers and agriculturists of the French Basque Country, promoted by the agrarian union, Laborarien Batasuna. Initially, this institution wasn't recognised, and its function was illegal. Now, its function is regulated and receives subventions from the Regional Council of Aquitaine.

In 2012, the French government proposed the creation of a single commonwealth for all of the towns in French Basque Country, under two conditions: being approved by at least half of the 158 communes in the historic territory, and that at least half of the nearly 300,000 residents be represented within this historic territory. After a process of municipal meetings, on May 2, 2016, both conditions were met.[12]

On 1 January 2017, the Agglomerate Community of Basque Country,[13][14] was created: an intercommunal cooperation movement (EPCI), which promotes a greater level of autonomy, with the French administrative categorization as an official territorial administrative structure with greater abilities than a pays, but fewer than a French department, and that is made up of a union of ten commonwealths and 157 of the 159 Basque communes, plus one Béarnese community.

History

Prehistoric era

The oldest human remains that are known of in the territory of the current French Basque Country are approximately 150,000 years old. Some houses have been found on the terraces of the Adour River, in Ilbarritz (Bidart), Sainte-Pierre-d’Irube, and Mouguerre. In the Middle Paleolithic era (700,000-100,000 years ago), neanderthals inhabited this area. At the beginning they lived in the open air and later in caves, like the one in Isturits. Cro-magnon people appeared during the Upper Paleolithic (9000-50,000 years ago).

Many artistic objects from the Magdalenian era (9000-14,000 years ago) have been found in Isturits.

The most well-known object found is a bird bone with three holes in it in the shape of a txistu. Moving into the Mesolithic era, humans began to live outside of caves, despite the fact that these were still used until a much later date. Also, during this era, the arts of ceramics, agriculture, and raising livestock were discovered.

During the Neolithic era (4000-3000 B.C.E.), new techniques for the use of metals and agriculture arrived.

Antiquity

The present-day territory was inhabited by the Tarbelli and the Sibulates, tribal divisions of the Aquitani. When Caesar conquered Gaul, he found all the region south and west of the Garonne inhabited by a people known as the Aquitani, who were not Celtic and are modernly regarded as Basques (see Aquitanian language). In the early Roman times, the region was first known as Aquitania, and by the end of the 3rd century, when the name Aquitania was extended until the Loire river, as Novempopulania (Aquitania Tertia). Its name in Latin means the nine peoples, as a reference to the nine tribes that inhabited it:

- The Tarbelli lived along the coast of Labourd and Chalosse, near Aquae Tarbellicae (Dax)

- The Ausci in the Gers and the city of Elimberrum (Auch)

- The Bigerriones from Bigorre in Turba (Tarbes)

- The Convenae in the Comminges, Lugdunum (Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges)

- The Consorani, who occupied Couserans (Saint-Lizier)

- The Lactorates in Lomagne, Lactura (Lectoure)

- The Elusates, in lower Armagnac with the city of Elusa (Eauze)

- The Vocates (Vassei or Vocates) in the southeast of Gironde or Bazadais, with its capital in Cossium (Bazas)

- The Boii in Pays de Buch, lived in the city of Lamothe (Le Teich)

The region reached a high level of Romanization, as many of the toponyms with Latin or Celtic suffixes, such as -acum or -anum, demonstrate. In the north of the current French Basque Country, these (toponyms) multiply: Loupiac, Gaillan, etc. However, in the southeast of the territory, the less Romanized area, toponyms with Basque suffixes are abundant: -ousse, -ous, -ost, and -oz, such as Biscarrosse and Almandoz for example; some inscriptions have words similar to Basque on them.

Middle Ages

After the Germanic and Slavic invasions that caused the fall of the Roman Empire, the ancient province began to be known under the term Wasconia according to texts by Frankish chroniclers, mainly Gregory of Tours and the Chronicle of Fredegar from the 6th century,[15] and was differentiated from the trans-pyrenean territories that later chroniclers from the Ravena Cosmograph named Spanoguasconia.

In the year 418, the Visigoths moved to the region due to a federation pact or foedus made with Rome, but they had to leave in 507 as a consequence of their defeat against the Merovingian dynasty belonging to King Clovis I in the battle of Vouillé.[16] After Clovis I's death in 511, the heirs to the Merovingian throne organized part of their northern possessions with regards to the main entities of Neustria and Austrasia under the direct control of the sovereigns, while the rest of their territorial possessions were organized into autonomous entities led by the powerful officials of the kingdom: counts, dukes, patricians, and vice chancellors according to the traditional Merovingian decentralized power structure.[17]

In Wasconia and the Pyrenean periphery in Vasconum saltus, armed incursions and confrontations with Merovingian officials were frequent during the last third of the 6th century. Venantius Fortunatus' chronicles cite the fights sustained up until 580 with the Frankish king Chilperic I and the comes from Bordeaux, Galactorio,[18] while Gregory of Tours wrote about the incursions Duke Austrobald faced in 587 with posterity to the defeat of Duke Bladastes in 574 in Soule.[19]

After the Basque rebellions against Roman feudalism in the late 4th and 5th century, the area eventually formed part of the independent Duchy of Vasconia in 602, a blur ethnic polity stretching south of the Garonne River that broke up from the 8th to 9th century, following the Carolingian expansion, the pressure of Norman raids and feudalism. The County of Vasconia was created extending around the Adour River. According to Iñaki Bazán,[20] after the creation of the Duchy, the Frankish kings Theuderic II and Theudebert II would exercise better military control over the area such as better tax collection and judicial administration, placing Duke Genial at the forefront. Later, between 635-638, King Dagobert I set out on a campaign for the repression of the Vascon inhabitants that would allow their submission.[20]

In the 8th century a second autonomous Duchy of Gascony was created, and by the end of the 9th century Guillermo Sanchez was named the duke of all Vascons. Some years later, Guy Geoffroy united the duchies of Vasconia and Aquitania (with the Poitiers county).

During this period, northern Basques surely participated in the successive battles of Roncevaux against the Franks, in 778, 812 and 824. Count Sans Sancion detached from the Franks and became the independent commander of Vasconia, but got involved in the Carolingian dynastic wars over succession after taking over Bordeaux (844), supporting the young Pepin II to the throne of Aquitaine. He became Duke of Vasconia after submitting to Charles the Bald (851).

At this point, Basque language was losing ground to Vulgar Latin and written Latin and was increasingly confined to the lands around the Pyrénées. Since 963, the town Saint-Sever is mentioned as caput vasconiae, interpreted as "limit of Vasconia" or "prominence of Vasconia" (on account of its location on a hill overlooking the plains of Vasconia).

The evangelization of the territory that today comprises French Basque Country was slow and precarious. Beginning in the 9th century, and in part due to the peregrination to Santiago de Compostela, a stable and long-lasting ecclesiastic organization was implanted in the region. The most important trails leading to Santiago passed through the region, and this greatly influenced the development of the trails and the villas in the territory.

Politics and institutions

The lands to the south of the Adour became Labourd, encompassing initially a bigger region than the later territory around the Nive (Errobi) and the coast. In 1020 Gascony ceded its jurisdiction over Labourd, then also including Lower Navarre, to Sancho the Great of Pamplona. This monarch made it a Viscounty in 1023 with its capital in Bayonne, which gave vassals to the King and Queen of Navarre until 1193. The area became disputed by the Angevin Dukes of Aquitaine until 1191 when Sancho the Wise and Richard Lionheart agreed to divide the country, Labourd remaining under Angevin sovereignty and Lower Navarre under Navarrese control.

All vacant land, forests, and waters under this Viscounty belonged to the King and everyone had the right to use them, whether they were nobles or not. Nobles did not have any feudal rights and justice rested solely in the hands of the King. The Biltzar, the only existing assembly, was in charge of distributing taxes and charges, and its delegates were chosen by the etxeko-jaun of the parishes. Furthermore, parish assemblies that administrated the collective goods of each parish existed. In 1215, Bayonne separated from Labourd, ruling from that moment on through its council. From the end of the 12th century until the French Revolution, Ustaritz was the capital of Labourd. Bayonne continued to be the economic hub of the area until the 19th century. However, above all, it was the port of Navarre that connected it to the North of Europe.

Meanwhile, Soule (Zuberoa) was constituted as an independent viscounty, generally supported by Navarre against the pretensions of the Counts of Béarn, though at times also it admitted a certain Angevin overlordship.[21] With the end of the Hundred Years' War, Labourd and Soule passed to the Crown of France as autonomous provinces (pays d'état).

After the conquest of Upper Navarre by Castile in 1512–21, the still independent north Pyrenean part of Navarre took the lead of the Huguenot party in the French Wars of Religion. In this time, the Bible was first translated into the Basque language.[22] Eventually Henry III of Navarre became King of France but kept Navarre as a formally independent state until 1620–24, when this separation was suppressed.

In 1634, Axular, in his literary work Gero, gives a rough description of the extent of Basque at the time: The language comprised all the provinces now known as Basque Country "and [in] so many other places". After Axular's accomplished book, other Basque writing authors followed suit, especially in Labourd, a district thriving on whale hunting. In 1579, an important handbook for navigation was published by Martin Oihartzabal, the Navigational Pilot, offering guidance and useful landmarks found in Newfoundland and other Basque traditional fisheries. In 1677 it was translated to Basque by Pierre Etxeberri. However, during the 17 and 18th century, that activity saw a gradual decline as the English took over from the Basques.

The Renaissance and witch trials

The 16th century was probably the most tragic for the inhabitants of the French Basque Country in its history. The recurring French-Spanish conflict between 1512 and 1659 and the French Wars of Religion that lasted 30 years sowed terror and misery.

On the other hand, the accusations made in the Parliament of Bordeaux motivated Labourd in sending the councilor Pierre de Lancre. He burned around 200 women, children and priests by forcing them to confess through torture. Pierre de Lancre was responsible for the witch hunt in Labourd. He believed women had a sinful nature, and that they were so dangerous that one judge alone could not judge a woman because men are weak. He said that a tribunal made up of several men was necessary to do so.

However, after overcoming the disasters suffered, a sort of renaissance was lived during the 17th century. Among other things, Rabelais published his Gargantua and Pantagruel, and Etxepare wrote the first printed text in Basque.

Territories of the French Basque Country and the French monarchy

With the conquest of the castles of Mauléon and Bayonne in 1449 and 1451 respectively, Labourd and Sola were under the domain of the French crown. When Henry III of Navarre took the French throne at the end of the 16th century (as Henry IV), Lower Navarre was incorporated into the French Royal patrimony (becoming the King of France and Navarre).

Modern period

The three Northern Basque provinces still enjoyed considerable autonomy until the French Revolution suppressed it radically, as it did elsewhere in France, eventually creating the department of Basses-Pyrénées, half-Basque and half-Gascon (Béarn, a former sovereign territory). Louis XVI of France summoned the Estates General to discuss problems of state. This assembly united the three estates: nobles, clerics, and the common people (the third estate). Third estate representatives of the Basques provinces attending the Estates-General of 1789 and the following national assemblies in Paris rejected the imposition of an alien political-administrative design, regarding the events with a blend of disbelief and indignation. The brothers Garat, representatives of Labourd, defended against a hostile audience the specificity of their province and that of the Basques, putting forward instead the establishment of a Basque department.[23] However, eventually the brothers Garat from Labourd voted for the new design out of hopes to get a say in future political decisions. In 1790 the Lower Pyrenees department project arrived, uniting the ancient Basque countries with Béarn. The reorganization favored the Bayonne bishopric that included the entire department (up to the Lescar and Oloron coasts that disappeared, and part of the Dax).

The three Basque provinces were then shaken by traumatic events after the intervention of the French Convention army during the War of the Pyrenees (1793–95). Besides prohibiting the native Basque language for public use ("fanaticism speaks Basque"), an indiscriminate mass-deportation of civilians followed resulting in the expulsion from their homes of thousands and a death toll of approx. 1,600 in Labourd.[24][25]

The Basques started to be forcibly recruited for the French army, with large numbers of youths in turn deciding to run away or defect among allegations of mistreatment, so starting a trend of exile and emigration to the Americas that was to last for more than a century.

The mutual hostility and lack of trust between the new regime and the European monarchies led to the creation of the General European Coalition against revolutionary France. At first, French Basque Country stayed at the margins of the conflict, since Spain stayed neutral, but in 1793, France declared war on Spain. The political situation after the mass-deportation of civilians improved when General Moncey led the French to a counterattack in June 1794, expelling the Spanish, and even entering Gipuzkoa. Pinet and Cavaignac went to Spain to manage conquered territory, courting the possibility of annexing it to France. After the fall of Robespierre, General Moncey forced the removal of Pinet and Cavaignac, who had managed to have a falling out with the Gipuzkoans. Due to this, they threw themselves into a desperate guerilla war, an antecedent to that of 1808. On July 22, the Treaty of Basilea was signed and the conflict ended, giving rise to a period of relative peace and prosperity.[26]

It became a matter of concern discussed by Napoleon Bonaparte and Dominique Garat. As of 1814, traditional cross-Pyrenean trade fell conspicuously, starting a period of economic stagnation. Eventually, trade across the Pyrénées border was cut off after the First Carlist War, with large numbers further departing to the Americas in search for a better life. In Soule, the emigration trend was mitigated by the establishment circa 1864 of a flourishing espadrille industry in Mauleon that attracted workers from Roncal and Aragon too. Others took to smuggling, a rising source of revenue.

The 19th century to the present

The mid-1800s were years of decay and yearning for the time before the French Revolution. The Basques divided into Republicans, laicist Jacobins (but for a nuanced position held by Xaho), and Royalists (traditional Catholics), with the latter prevailing among the Basques.[27] Shepherding and small mining and agricultural exploitations were the main economic activities along with an increased presence of customs officials, both local and non-Basques.

The railway arrived at Hendaye in 1864 (Mauleon in 1880), increasing the flow of freight and people from outside the Basque Country that replaced especially on the coast native inhabitants by non-Basque population, with Biarritz as the most revealing case, in a colonie de peuplement type of settlement (Manex Goihenetxe, Eneko Bidegain). Elitist tourism gained momentum as of 1854 (Kanbo, Saint-Jean-de-Luz, Biarritz, Hendaye, etc.), as the high nobility (e.g. Eugénie de Montijo) chose to take healing baths in spa resorts and get close to nature.

In 1851, the first Lore Jokoak took place in Urruña (restored floral games tradition) organized by the scholar of Basque-Irish origin Antoine d'Abbadie (Anton Abbadia), followed by several more editions up to 1897. Other political and cultural events in fellow Basque districts to the south of the Pyrenees had an impact in the French Basque Country, especially in church related circles (periodicals like Eskualduna, 1887), the only institution that still spoke to the people in their language. That could not prevent Basque language from further receding to local and domestic circles. In 1914, Basque ceased to be the trading language with the local middle and higher class customers at the Mauleon marketplace (Soule).

The Basques could not avoid getting entangled in World War I when they were drafted to the front. While across the border Gipuzkoa and Biscay thrived on their shipbuilding and steel processing industry supplying the European war effort,[28] continental Basques under the age of 49 were required to the front of north-east France.[29] From the beginning and as the slaughter of the trenches wore on, thousands of Basques objected to military service, defected and fled to the south or the Americas.[30] However, war took a heavy toll, 6,000 died in the front, a 3% of the French Basque population.[31] It also produced the idea in the Basque psyche of being a component part of the French nation, fostered by the above weekly Eskualduna on the grounds that "God champions France."[32]

In the last 200 years, the territory has shown a slow demographic rise: 126,493 (in 1801); 162,365 (1851); 226,749 (1979) (79% in Labourd, 13% in Lower Navarre, 8% in Soule); 259,850 (1990) (81%; 13%; 6% respectively); 262,000 (1999 census). On January 29, 1997, the area was made an official pays of France named Pays Basque, i.e., a representative body promoting several activities, but without its own budget.

Culture

Languages

Neither Basque nor any of the other regional languages in France, such as Catalan, Breton or Occitan, have official recognition in France. According to the second article of the French Constitution, "the language of the Republic is French", and, despite several attempts to add "with respect to the regional languages that are part of our heritage" by 44 deputies in 2006, the proposal was rejected by 57 votes against and 44 in favor.[33]

Northern Basques continue to practice many Basque cultural traditions. The town of Saint-Pée-sur-Nivelle is well known for its Herri Urrats celebration.[34]

According to a 2006 survey,[35] 22.5% were bilinguals (French-Basque), 8.6% were French speakers who understand Basque, and 68.9% were not Basque speakers. But the results were very different in the three zones. In the inner land (Lower Navarre and Soule), 66.2% speak or understand Basque. In the coast (Labourd), the figure stands at 36.9%. And in the B.A.B. urban zone (Bayonne-Anglet-Biarritz), only 14.2% speak or understand Basque (20% of B.A.B. can speak or understand Gascon). The proportion of French-Basque bilinguals fell from 26.4% in 1996 to 22.5% in 2006.

On the coast, where the largest cities are located, the predominant language is French, for example, in the Bayonne-Anglet-Biarritz agglomeration, Basque is spoken by 10% of the population. However, in the rural interior of the Northern Basque Country, Basque is the predominant language, spoken by the majority of the population.[36]

Basque

Basque,[37] a continuum of Aquitaine (or Proto-Basque) spoken in this region since before the Roman era,[38] does not have official status but it does have some acknowledgement, so that it can be studied in school and be used as a secondary language by the institutions in the area.

According to the current division created by Koldo Zuazo, there are two dialects spoken in French Basque Country: Souletin (zuberera) and the Navarro-Lapurdian dialect (nafar-lapurtera), whose delimitations don't correspond to the three Basque provinces. The spoken languages of Labourd and Lower Navarre are part of a linguistic continuum without established borders. It ends in the Amikuze or Mixe Country region and the Soule province, where a dialect with great cohesion and defined traits can be found: Souletin. In Zuazo's opinion, this may be due to the fact that this territory has been separated administratively from the other two, and that the differences in speech have been intensified by the lack of interaction.

The literary tradition in French Basque Country, especially in Labourd, has had great importance in the history of the Basque language. The first Basque writers on that side of the Pyrenees took the language from the Labourd coast as their base language for literature, more specifically the triangle formed by Ciboure, Sare, and Sainte-Jean-de-Luz. The language has evolved in the literary plane from classical Labourd dialect used by writers in the Sare School, to the literary Navarro-Lapurdian dialect, a sort of Basque unified in French Basque Country made concrete by a grammar book by Pierres Lafitte Ithurralde in the 1940s. In many ways, it is considered one of the predecessors of Standard Basque, and it currently survives as an unrecognized version of unified Basque. In other words, it is a unified Basque with lexical and morphological elements unique to the region.

The Navarro-Lapurdian dialect and Souletin have common characteristics that distinguish them from other Basque dialects, such as the pronunciation of /h/ (according to Koldo Mitxelena, it was lost around the 13th century in the Pyrenees territories due to Aragonese influence and became extinct on the Labourd coast around the 19th century, according to Louis Lucien Bonaparte), the differences in speech in the grammatical cases of Nor (absolutive) and Nork (ergative), and the use of the root *eradun in front of *edun used in speech on the other side of the Bidasoa (deraut vs. diot). The Royal Academy of the Basque Language took into account the four centuries of literary tradition of this region when it began the unification project.

According to the theory of waves or gradients, the Souletin and Biscayan dialects are the dialects that have conserved the largest number of archaisms due to their geographical location, but at the same time, they had the greatest influence from other languages (Mitxelena). This is why Souletin is considered innovative with regards to its phonology (influenced mainly by Gascon), but conservative in its lexicon and morphology. Souletin relies on a written literary tradition of great importance, but something worth noting is the oral tradition, since ancient ballads and songs have been passed on from generation to generation up until current times, being rescued by musicians and singer-songwriters in the second half of the 20th century. The Soule people have a firm popular theatre tradition, and pastorals and masques reflect this. The plays are performed by entire towns, who turn into an instrument for the reaffirmation of Souletin identity, which has suffered a worrying demographic decline.

Acknowledgement of Basque and Gascon

Neither Basque nor any of the other regional languages of France (like Alsatian, Breton, or Occitan) have official recognition in France. According to the second article of the French Constitution, “the language of the Republic is French” and, despite many attempts to add “with respect to regional languages that are a part of our patrimony” to the text by 44 deputies in 2006, the proposal was denied by 57 votes against the 44 votes in favor.[39]

Despite this, bilingual signage exists at the municipal level for traffic (trilingual in places like Bayonne).

Below is an extract from the report of the Observatory of Linguistic Rights of Euskal Herria:[40]:

In the French State (Labourd, Lower Navarre, and Soule provinces). With the constitutional reform of 1992, France declared French the language of the Republic. Although Article 2.1 the Constitution proclaims the beginning of equality, it only recognizes legal protection for French, leaving the rest of the languages of the Republic in a state/environment of tolerance. Other legal texts that strengthen the status of French are Law 75-1349, from 31 December 1975, and the law that replaced it, Law 94-665, from 4 August 1994, known as the Toubon Law (relative à l’emploi de la langue française). Article 21 of the Toubon Law states that the establishments made with this law will not be applied with prejudice of the norm and legislation corresponding to the regional languages of France, and that such a law does not go against the use of those languages. But that article lacks usefulness, because no legislation or norm exists for the regional languages of France. In order to give the Basque language legal recognition, it would be necessary to modify the Constitution of the Republic. French speakers of Basque do not then have any recognized linguistic rights. And thus no guaranteed linguistic rights.

— Observatory of the Linguistic Rights of Euskal Herria

Since 1994, the ikastolas (Basque-medium schools) are recognized as educational establishments, with an association model, although they don't receive any state aid. Professors in the ikastolas are under the responsibility of the French Education Ministry. In 2000, the Basque-French federation of ikastolas, Seaska, decided to end negotiations with the French educational administration to integrate ikastolas into the public education system of France, since the conditions it set did not guarantee their education model.[41] Currently, the ikastolas are financed largely by the parents in a cooperative system and by various activities organized in favor of Basque, such as Herri Urrats (Popular Step), which Basque speakers in Spain and France attend to do a walk for solidarity. Thanks to the participation of individuals, companies, and communities, Herri Urrats, in collaboration with Seaska, has allowed for the opening of 20 elementary schools, three highschools and an institution for secondary education since 1984.

In 2003, the Basque government and the members of the Department of Public Works of the French Basque Country signed the protocols that allowed the collaboration between the various Basque organisms and institutions to encourage a linguistic policy on both sides of the Spanish-French border; the Public Institution of Basque (Euskararen Erakunde Publikoa) was born due to this accord in French Basque Country.

Politics

There is a Basque nationalist political movement going back to 1963 with the Embata movement (forbidden in 1974), followed up during the 2000s by Abertzaleen Batasuna and others. They seek a split of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques into two French departments: Pays Basque and Béarn. Some other nationalist parties are EAJ, and EA with a reduced, almost symbolic presence, especially when compared to the southern Basque Country across the border. Since 2007, they gather around the electoral platform Euskal Herria Bai earning roughly 15% of the votes in the district elections.

In the 1980s and 1990s, an armed group called Iparretarrak (‘the Northerners’) used violence to seek independence. It disbanded in the 1990s.

Economy

The Northern Basque Country has 29,759 companies, 107 companies for 1,000 inhabitants and an annual growth of 4.5% (between 2004 and 2006).[42]

66.2% of companies are in the tertiary sector (services), 14.5% in the secondary sector (manufacturing) and 19.3% in the primary sector (mainly agriculture, agribusiness, fishing and forestry). This includes an AOC wine: Irouléguy AOC.

Although the Northern Basque Country is part of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques for most administrative entities, it does have its own Chamber of Commerce (the CCI Bayonne-Pays-Basque) and a distinct economy with a pole of competences around the boardsports industry including companies such as Quiksilver and Volcom based on the Basque Coast.

See also

- Aquitani

- Bayonne ham

- Communauté d'agglomération du Pays Basque

- Duchy of Vasconia

- Izarra, a local liquor

- Eusko, local currency

- Kingdom of Navarre

- Northern Catalonia

References

- "Abian da Euskal Elkargoa [The Basque Community kicks off]". EITB. 2017-01-02. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- Sabathlé, Pierre (2017-01-23). "Jean-René Etchegaray élu président de la communauté d'agglomération Pays basque". SudOuest. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- "Aujourd'hui, 10 intercommunalités en Pays Basque". Communauté Pays Basque. Communauté Pays Basque. 2015. Retrieved 2017-02-03.

- "Basque Eurocity". MOT, Mission Opérationelle Transfrontalière. French Govt. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- Página francesa donde consta el país. Consultado el 16 de mayo de 2017 (en francés)

- Ley 95-115 (denominada también Ley Pasqua o LOADT) de orientación para la organización y el desarrollo territorial (en francés).

- Ley 99-533 (denominada también Ley Voynet o LOADDT) de orientación para la organización y el desarrollo territorial (en francés).

- Electos de Iparralde votan a favor de la Colectividad Territorial

- El País Vasco francés o la pugna de identidades

- Association des Elus pour une Departement Basque

- http://www.ehlgbai.org/es

- "Iparralde cumple las dos condiciones para la creación de la Mancomunidad". Eitb.

- Banatic, página oficial de las Mancomunidades francesas (en francés)

- Orden nº 64-2016-07-13-015, publicado el 13 de julio de 2016 (en francés, páginas de 41 a 54)

- Adolf Schulten, 1927, Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos. RIEV, 18, 2.Las referencias sobre los Vascones hasta el año 810 después de J.C.

- (Bazán 2006:245)

- Archibald R. Lewis, The Dukes in the Regnum Francorum, A.D. 550–751., en Speculum, Vol. 51, No. 3 (Jul., 1976), pp. 381–410. JSTOR 2851704

- (Schulten 1927:234)

- Grégoire de Tours, Histoire des Francs, edición J.-L.-L. Brière, Paris 1823. Tomo II, Libro IX, De l'année 587 à l'année 589. Gontran, Childebert II et Clotaire II, Rois pag. 8. Disponible el 16/11/2006 en bnf.fr

- (Bazán 2006:246)

- Baja Navarra y Zuberoa (La Historia y los Vascos – Vascon.Galeon.com)

- "Joanes Leizarraga Vida Y Obra" (PDF). Euskomedia. Retrieved 2008-01-28. Article in Spanish

- Bolinaga, Iñigo (2012). La alternativa Garat. Donostia-San Sebastián: Txertoa. pp. 50–53, 70–71. ISBN 978-84-7148-530-4.

- Etxegoien (Xamar), Juan Carlos (2009). The Country of Basque (2nd ed.). Pamplona-Iruñea, Spain: Pamiela. p. 23. ISBN 978-84-7681-478-9.

- Bolinaga, Iñigo. 2012, p. 87

- Sánchez Arreseigor, Juan José: Vascos contra Napoleón; Editorial Actas, 2010 Madrid. Pag. 30 a 37

- "Republicanismo en Euskal Herria: Iparralde". Auñamendi Entziklopedia. EuskoMedia. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- "La economía vasca durante el período 1914-1918". Auñamendi Entziklopedia. EuskoMedia. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- Bidegain, Eneko (2012). Lehen mundu gerra "Eskualduna" astekarian [World War I on the Weekly Euskalduna] (PDF). Universities UB/BU and UPV/EHU. p. 652. ISBN 978-84-8438-511-0. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- Bidegain, Eneko. 2012, pp. 562-571

- Bidegain, Eneko. 2012, p. 174

- Bidegain, Eneko. 2012, pp. 606, 658-659

- "París dice que hacer oficial el euskera ataca la unidad francesa" - El Correo, 22 de diciembre de 2006

- "Celebration of Herri Urrats, traditional festival to help Basque language schools in the Northern Basque Country". Euskalkultura.com: Basque Heritage Worldwide (BETA). Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- Fourth Sociolinguistic Survey. 2006: Basque Autonomous Community, Northern Basque Country, Navarre, Basque Country, Basque Government, Vitoria-Gasteiz, 2008, ISBN 978-84-457-2777-5.

- Euskalgintza IV

- Louis Lucien Bonaparte, sobrino de Napoleón Bonaparte, hizo la primera clasificación de los dialectos en el siglo XIX basada únicamente en criterios lingüísticos. Realizó cuatro clasificaciones diferentes. La clasificación definitiva la recogió en su obra "Le verbe basque en tableaux", donde diferenció ocho dialectos: vizcaíno, guipuzcoano, altonavarro del norte, altonavarro del sur (hoy día prácticamente extinto), bajonavarro del oeste, bajonavarro del este, labortano y suletino. En ellos apreció 25 subdialectos y 50 variantes.

- Las primeras palabras escritas en euskera son las encontradas en las estelas funerarias vascoaquitanas y pirenaicas de la época romana (siglo I). Podría tratarse de nombres de dioses y diosas: sembe > seme (hijo), anderex > andere (señora), cison > gizon (hombre), nescato > neskato (muchacha)... Aunque en la actualidad se corresponde con nombres comunes en nuestro vocabulario, (Euskararen jatorriari buruzko teoriak, en euskera).

- "París dice que hacer oficial el euskera ataca la unidad francesa" - El Correo, 22 de diciembre de 2006

- "Cinco estatus diferentes para la lengua vasca y los derechos lingüísticos - Observatorio de Derechos Lingüísticos de Euskal Herria

- Seaska: Les racines de l'avenir (en francés).

- "Invest Pays Basque". CCI Bayonne. Archived from the original on 2013-07-01. Retrieved 2008-06-05. Invest-PaysBasque.com

External links

![]() Media related to Northern Basque Country at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Northern Basque Country at Wikimedia Commons