Barbary lion

The Barbary lion was a Panthera leo leo population in North Africa that is regionally extinct.[4] This population occurred in Barbary Coastal regions of Maghreb from the Atlas Mountains to Egypt and was eradicated following the spread of firearms and bounties for shooting lions.[1] A comprehensive review of hunting and sighting records revealed that small groups of lions may have survived in Algeria until the early 1960s, and in Morocco until the mid-1960s.[5]

| Barbary lion | |

|---|---|

| |

| A male Barbary lion in Algeria. Photo credit: Alfred Edward Pease, 1893.[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | |

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera leo leo[2][3] | |

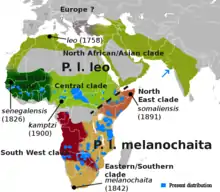

Until 2017, the Barbary lion was considered a distinct lion subspecies.[6][3][2] Results of morphological and genetic analyses of lion samples from North Africa published in 2008 showed that the Barbary lion does not differ significantly from lion samples collected in West and northern parts of Central Africa.[7] It falls into the same phylogeographic group as the Asiatic lion,[8] and is also closely related to lion populations in West Africa.[9]

The Barbary lion was also called "North African lion",[1] "Berber lion", "Atlas lion",[10] and "Egyptian lion".[11]

Characteristics

Barbary lion zoological specimens range in colour from light to dark tawny. Male lion skins had short manes, light manes, dark manes or long manes.[12] Head-to-tail length of stuffed males in zoological collections varies from 2.35 to 2.8 m (7 ft 8 1⁄2 in to 9 ft 2 in), and of females around 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in). Skull size varied from 30.85 to 37.23 cm (12 5⁄32 to 14 21⁄32 in). Some manes extended over the shoulder and under the belly to the elbows. The mane hair was 8 to 22 cm (3 to 8 1⁄2 in) long.[13][12][14]

In 19th century hunter accounts, the Barbary lion was claimed to be the largest lion, with a weight of wild males ranging from 270 to 300 kg (600 to 660 lb). Yet, the accuracy of such data measured in the field is questionable. Captive Barbary lions were much smaller but kept under such poor conditions that they might not have attained their full potential size and weight.[15]

The colour and size of lions' manes was long thought to be a sufficiently distinct morphological characteristic to accord a subspecific status to lion populations.[16] Mane development varies with age and between individuals from different regions, and is therefore not a sufficient characteristic for subspecific identification.[17] The size of manes is not regarded as evidence for Barbary lions' ancestry. Instead, results of mitochondrial DNA research support the genetic distinctness of Barbary lions in a unique haplotype found in museum specimens that is thought to be of Barbary lion descent. The presence of this haplotype is considered a reliable molecular marker to identify captive Barbary lions.[18] Barbary lions may have developed long-haired manes, because of lower temperatures in the Atlas Mountains than in other African regions, particularly in winter.[15] Results of a long-term study on lions in Serengeti National Park indicate that ambient temperature, nutrition and the level of testosterone influence the colour and size of lion manes.[19]

Taxonomic history

Felis leo was the scientific name proposed by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 for a lion type specimen from Constantine, Algeria.[20] Following Linnaeus's description, several lion zoological specimens from North Africa were described and proposed as subspecies in the 19th century:

- Felis leo barbaricus described by the Austrian zoologist Johann Nepomuk Meyer in 1826 was a lion skin from the Barbary Coast.[21]

- Felis leo nubicus described by Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville in 1843 was a male lion from Nubia that had been sent by Antoine Clot from Cairo to Paris and died in the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes in 1841.[22]

In the 20th century, there has been much debate and controversy among zoologists on lion classification and validity of proposed subspecies:

- In 1939, Glover Morrill Allen considered F. l. barbaricus and nubicus synonymous with F. l. leo.[23]

- Reginald Innes Pocock subordinated the lion to the genus Panthera, when he wrote about the Asiatic lion.[24]

- In 1951, John Ellerman and Terence Morrison-Scott recognized only two lion subspecies in the Palearctic realm, namely the African lion Panthera leo leo and the Asiatic lion P. l. persica.[25]

- Some authors considered P. l. nubicus a valid subspecies and synonymous with P. l. massaica.[13][26][27]

- In 2005, P. l. barbarica, nubica and somaliensis were subsumed under P. l. leo.[3]

- In 2016, IUCN Red List assessors used P. l. leo for all lion populations in Africa.[4]

In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the Cat Specialist Group subsumed the lion populations in North, West and Central Africa and Asia to P. l. leo.[2]

Genetic research

Results of a phylogeographic analysis using samples from African and Asiatic lions was published in 2006. One of the African samples was a vertebra from the National Museum of Natural History (France) that originated in the Nubian part of Sudan. In terms of mitochondrial DNA, it grouped with lion skull samples from the Central African Republic, Ethiopia and the northern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[18]

While the historical Barbary lion was morphologically distinct, its genetic uniqueness remained questionable.[28] In a comprehensive study about the evolution of lions in 2008, 357 samples of wild and captive lions from Africa and India were examined. Results showed that four captive lions from Morocco did not exhibit any unique genetic characteristic, but shared mitochondrial haplotypes with lion samples from West and Central Africa. They were all part of a major mtDNA grouping that also included Asiatic lion samples. Results provided evidence for the hypothesis that this group developed in East Africa, and about 118,000 years ago traveled north and west in the first wave of lion expansion. It broke up within Africa, and later in West Asia. Lions in Africa probably constitute a single population that interbred during several waves of migration since the Late Pleistocene.[7] Genome-wide data of a wild-born historical lion specimen from Sudan clustered with P. l. leo in mtDNA-based phylogenies, but with a high affinity to P. l. melanochaita.[9]

Former distribution and habitat

Historical accounts indicate that in Egypt lions occurred in the Sinai Peninsula, along the Nile, in the Eastern and Western Deserts, in the region of Wadi El Natrun and along the maritime coast of the Mediterranean.[29] In the 14th century BC, Thutmose IV hunted lions in the hills near Memphis.[30] The growth of civilizations along the Nile and in the Sinai Peninsula by the beginning of the second millennium BC and desertification contributed to isolating lion populations in North Africa.[31]

Historical sighting and hunting records from the 19th and 20th centuries show that lions inhabited the range countries of the Atlas Mountains from Tunisia to Morocco.[5]

In Libya, the Barbary lion persisted along the Mediterranean coast until the beginning of the 18th century, and was extirpated in Tunisia by 1890.[32]

In Algeria, the Barbary lion occurred in the forested hills and mountains between the Pic de Taza in the east, Ouarsenis in the west and the Chelif River plains in the north. Lions also inhabited the forests and wooded hills of the Constantine Province and south into the Aurès Mountains.[1] In the 1830s, lions may have already been eliminated along the coast and near human settlements.[33] By the mid-19th century, the lion population had massively declined, since bounties were paid for shooting lions. The cedar forests of Chelia and neighbouring mountains harboured lions until about 1884.[1] They disappeared in the Bône region by 1890, in the Khroumire and Souk Ahras regions by 1891, and in Batna Province by 1893.[34] The last known sighting of a lion in Algeria occurred in 1956 in Beni Ourtilane District.[5]

In Morocco, the last recorded shooting of a wild Barbary lion took place in 1942 near Tizi n'Tichka in the Atlas Mountains. A small remnant population may have survived in remote montane areas into the early 1960s.[5]

Behaviour and ecology

In the early 20th century, when Barbary lions were not common anymore, they were sighted in pairs or in small family groups comprising a male and female lion with one or two cubs.[1] Between 1839 and 1942, sightings of wild lions involved solitary animals, pairs and family units. Analysis of these sightings indicate that lions retained living in prides even when under increasing persecution, particularly in the eastern Maghreb. The size of prides was likely similar to prides living in sub-Saharan habitats, whereas the density of the Barbary lion population is considered to have been lower than in moister habitats.[5]

When Barbary stags and gazelles became scarce in the Atlas Mountains, lions preyed on herds of livestock that were rather carefully tended.[35] They also preyed on wild boar and red deer.[36]

Sympatric predators in this area included the African leopard and Atlas bear.[6][37]

In captivity

_(18427026972).jpg.webp)

The lions kept in the menagerie at the Tower of London in the Middle Ages were Barbary lions, as shown by DNA testing on two well-preserved skulls excavated at the Tower between 1936 and 1937. The skulls were radiocarbon-dated to around 1280–1385 and 1420−1480.[31] In the 19th century and the early 20th century, lions were often kept in hotels and circus menageries. In 1835, the lions in the Tower of London were transferred to improved enclosures at the London Zoo on the orders of the Duke of Wellington.[38]

The lions in the Rabat Zoo exhibited characteristics thought typical for the Barbary lion.[39] Nobles and Berber people presented lions as gifts to the royal family of Morocco. When the family was forced into exile in 1953, the lions in Rabat, numbering 21 altogether, were transferred to two zoos in the region. 3 of these were shifted to a zoo in Casablanca, with the rest being shifted to Meknès. The lions at Meknès were moved back to the palace in 1955, but those at Casablanca never came back. In the late 1960s, new lion enclosures were built in Temara near Rabat.[15] Results of a mtDNA research revealed in 2006 that a lion kept in the German Zoo Neuwied originated from this collection and is very likely a descendant of a Barbary lion.[10] Five lion samples from this collection were not Barbary lions maternally. Nonetheless, genes of the Barbary lion are likely to be present in common European zoo lions, since this was one of the most frequently introduced subspecies. Many lions in European and American zoos, which are managed without subspecies classification, are most likely descendants of Barbary lions.[16] Several researchers and zoos supported the development of a studbook of lions directly descended from the King of Morocco's collection.[28]

At the beginning of the 21st century, the Addis Ababa Zoo kept 16 adult lions. With their dark, brown manes extending through the front legs, they looked like Barbary or Cape lions. Their ancestors were caught in southwestern Ethiopia as part of a zoological collection for Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia.[40]

Cultural significance

The lion appeared frequently in early Egyptian art and literature.[41] Statues and statuettes of lions found at Hierakonpolis and Koptos in Upper Egypt date to the Early Dynastic Period.[42] The early Egyptian deity Mehit was depicted with a lion head.[43] In Ancient Egypt, the lion-headed deity Sekhmet was venerated as protector of the country.[44] She represented destructive power, but was also regarded as protector against famine and disease. Lion-headed figures and amulets were excavated in tombs in the Aegean islands of Crete, Euboea, Rhodes, Paros and Chios. They are associated with Sekhmet and date to the early Iron Age between the 9th and 6th centuries BC.[45] The remains of seven mostly subadult lions were excavated at the necropolis Umm El Qa'ab in a tomb of Hor-Aha, dated to the 31st century BC.[46] In 2001, the skeleton of a mummified lion was found in the tomb of Maïa in a necropolis dedicated to Tutankhamun at Saqqara.[47] It had probably lived and died in the Ptolemaic period, showed signs of malnutrition and had probably lived in captivity for many years.[48]

In Roman North Africa, lions were regularly captured by experienced hunters for venatio spectacles in amphitheatres.[36][49]

Statue of Sekhmet in the temple of Ptah

Statue of Sekhmet in the temple of Ptah Lion statue dated to the Thirtieth Dynasty of Egypt 378−361 BC, exhibited in the Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre

Lion statue dated to the Thirtieth Dynasty of Egypt 378−361 BC, exhibited in the Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre llustration of a Barbary lion by Joseph Bassett Holder, 1898

llustration of a Barbary lion by Joseph Bassett Holder, 1898

Stuffed Barbary and Cape lions in the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle

Stuffed Barbary and Cape lions in the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle)_(18160964071).jpg.webp) The dromedary's relationships with the lion and mankind is depicted in this taxidermy diorama by Jules and Édouard Verreaux, which is called "Lion Attacking a Dromedary," and was acquired by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, in 1898[50]

The dromedary's relationships with the lion and mankind is depicted in this taxidermy diorama by Jules and Édouard Verreaux, which is called "Lion Attacking a Dromedary," and was acquired by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, in 1898[50]

See also

References

- Pease, A. E. (1913). "The Distribution of Lions". The Book of the Lion. London: John Murray. pp. 109−147.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 71–73.

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Panthera leo". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Bauer, H.; Packer, C.; Funston, P. F.; Henschel, P. & Nowell, K. (2016). "Panthera leo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T15951A115130419.

- Black, S. A.; Fellous, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Roberts, D. L. (2013). "Examining the Extinction of the Barbary Lion and Its Implications for Felid Conservation". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e60174. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...860174B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060174. PMC 3616087. PMID 23573239.

- Nowell, K. & Jackson, P. (1996). "African lion, Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1758)" (PDF). Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 17–21. ISBN 978-2-8317-0045-8.

- Antunes, A.; Troyer, J. L.; Roelke, M. E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Packer, C.; Winterbach, C.; Winterbach, H. & Johnson, W. E. (2008). "The Evolutionary Dynamics of the Lion Panthera leo revealed by Host and Viral Population Genomics". PLOS Genetics. 4 (11): e1000251. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000251. PMC 2572142. PMID 18989457.

- Bertola, L.D.; Jongbloed, H.; Van Der Gaag K.J.; De Knijff, P.; Yamaguchi, N.; Hooghiemstra, H.; Bauer, H.; Henschel, P.; White, P.A.; Driscoll, C.A.; Tende, T.; Ottosson, U.; Saidu, Y.; Vrieling, K. & de Iongh, H. H. (2016). "Phylogeographic patterns in Africa and High Resolution Delineation of genetic clades in the Lion (Panthera leo)". Scientific Reports. 6: 30807. Bibcode:2016NatSR...630807B. doi:10.1038/srep30807. PMC 4973251. PMID 27488946.

- Manuel, M. d.; Ross, B.; Sandoval-Velasco, M.; Yamaguchi, N.; Vieira, F. G.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Liu, S.; Martin, M. D.; Sinding, M.-H. S.; Mak, S. S. T.; Carøe, C.; Liu, S.; Guo, C.; Zheng, J.; Zazula, G.; Baryshnikov, G.; Eizirik, E.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Johnson, W. E.; Antunes, A.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Larson, G.; Yang, H.; O’Brien, S. J.; Hansen, A. J.; Zhang, G.; Marques-Bonet, T. & Gilbert, M. T. P. (2020). "The evolutionary history of extinct and living lions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (20): 10927–10934. doi:10.1073/pnas.1919423117. PMC 7245068. PMID 32366643.

- Burger, J.; Hemmer, H. (2006). "Urgent call for further breeding of the relic zoo population of the critically endangered Barbary lion (Panthera leo leo Linnaeus 1758)" (PDF). European Journal of Wildlife Research. 52 (1): 54–58. doi:10.1007/s10344-005-0009-z. S2CID 30407194. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-03. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Lion". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 83–95. ISBN 978-90-04-08876-4.

- Mazák, V. (1970). "The Barbary lion, Panthera leo leo (Linnaeus, 1758); some systematic notes, and an interim list of the specimens preserved in European museums". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 35: 34−45.

- Hemmer, H. (1974). "Untersuchungen zur Stammesgeschichte der Pantherkatzen (Pantherinae) Teil 3. Zur Artgeschichte des Löwen Panthera (Panthera) leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Veröffentlichungen der Zoologischen Staatssammlung. 17: 167–280.

- Mazák, J. H. (2010). "Geographical variation and phylogenetics of modern lions based on craniometric data". Journal of Zoology. 281 (3): 194–209. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00694.x.

- Yamaguchi, N.; Haddane, B. (2002). "The North African Barbary Lion and the Atlas Lion Project". International Zoo News. 49 (8): 465–481.

- Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I.; Cooper, A. (2006). "Lost populations and preserving genetic diversity in the lion Panthera leo: Implications for its ex situ conservation" (PDF). Conservation Genetics. 7 (4): 507–514. doi:10.1007/s10592-005-9062-0. S2CID 24190889. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-24.

- O'Brien, S. J.; Joslin, P.; Smith, G. L.; Wolfe, R.; Schaffer, N.; Heath, E.; Ott‐Joslin, J.; Rawal, P. P.; Bhattacharjee, K. K.; Martenson, J. S. (1987). "Evidence for African Origins of Founders of the Asiatic Lion Species Survival Plan". Zoo Biology. 6 (2): 99–116. doi:10.1002/zoo.1430060202.

- Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I. & Cooper, A. (2006). "The origin, current diversity and future conservation of the modern lion (Panthera leo)" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 (1598): 2119–2125. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3555. PMC 1635511. PMID 16901830. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2007.

- West, P. M.; Packer, C. (2002). "Sexual selection, temperature, and the lion's mane". Science. 297 (5585): 1339–1343. Bibcode:2002Sci...297.1339W. doi:10.1126/science.1073257. PMID 12193785. S2CID 15893512.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis Leo". Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). p. 41. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- Meyer, J. N. (1826). Dissertatio inauguralis anatomico-medica de genere felium. Doctoral thesis. Vienna: University of Vienna.

- Blainville, H. M. D. de (1843). "F. leo nubicus". Ostéographie ou description iconographique comparée du squelette et du système dentaire des mammifères récents et fossils pour servir de base à la zoologie et la géologie. Vol 2. Paris: J. B. Baillière et Fils. p. 186.

- Allen, G. M. (1939). "A Checklist of African Mammals". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College. 83: 1–763.

- Pocock, R. I. (1930). "The lions of Asia". Journal of the Bombay Natural Historical Society. 34: 638–665.

- Ellerman, J. R.; Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946 (Second ed.). London: British Museum of Natural History. pp. 312–313.

- Haas, S.K.; Hayssen, V.; Krausman, P.R. (2005). "Panthera leo" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 762: 1–11. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)762[0001:PL]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2017.

- West, P. M.; Packer, C. (2013). "Panthera leo Lion". In Kingson, J.; Happold, D.; Butynski, T.; Hoffmann, M.; Happold, M.; Kalina, J. (eds.). Mammals of Africa. Volume V. A & C Black. p. 149−159. ISBN 978-1-4081-8996-2.

- Black, S.; Yamaguchi, N.; Harland, A. & Groombridge, J. (2010). "Maintaining the genetic health of putative Barbary lions in captivity: an analysis of Moroccan Royal Lions" (PDF). European Journal of Wildlife Research. 56 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1007/s10344-009-0280-5. S2CID 44941372.

- Planhol, X. (2004). Le Paysage Animal. L'homme et la Grande Faune: Une Zoogéographie Historique. Paris: Fayard.

- Wilkinson, J. G. (1878). The manners and customs of the ancient Egyptians. Volume III (revised ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead and Co.

- Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Shapiro, B.; Sabin, R. (2008). "Ancient DNA analysis indicates the first English lions originated from North Africa". Contributions to Zoology. 77 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1163/18759866-07701002.

- Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1961). Simba: the life of the lion. Cape Town: Howard Timmins.

- Jardine, W. (1834). "The Lion". The Naturalist's Library. Mammalia Vol. II: the Natural History of Felinae. Edinburgh: W. H. Lizars. pp. 87−123..

- Joleaud, L. (1936). "Zoogéographie mammalogique". Étude géologique de la région de Bône et de La Calle. Alger: Bulletin du Service de la Carte Géologique de l’Algérie. p. 174.

- Johnston, H. H. (1899). "The lion in Tunisia". In Bryden, H. A. (ed.). Great and small game of Africa. London: Rowland Ward Ltd. pp. 562–564.

- Pease, A. E. (1899). "The lion in Algeria". In Bryden, H. A. (ed.). Great and small game of Africa. London: Rowland Ward Ltd. pp. 564–568.

- Johnston, H. H. (1899). "African bear". In Bryden, H. A. (ed.). Great and small game of Africa. London: Rowland Ward Ltd. pp. 607–608.

- Edwards, J. (1996). London Zoo from Old Photographs 1852–1914. London: John Edwards.

- Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "Wild Cats of Africa" (PDF). Wild Cats: status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland. pp. Plate I.

- Tefera, M. (2003). "Phenotypic and reproductive characteristics of lions (Panthera leo) at Addis Ababa Zoo". Biodiversity and Conservation. 12 (8): 1629–1639. doi:10.1023/A:1023641629538. S2CID 24543070.

- Porter, J. H. (1894). "The Lion". Wild beasts; a study of the characters and habits of the elephant, lion, leopard, panther, jaguar, tiger, puma, wolf, and grizzly bear. New York: C. Scribner's sons. pp. 76–134.

- Adams, B. (1992). "Two more lions from Upper Egypt: Hierakonpolis and Koptos". In Friedmann, R.; Adams, B. (eds.). The Followers of Horus. Studies Dedicated to Michael Allen Hoffman. Oxford: Oxbow Press. pp. 69–76.

- Wilkinson, T. A. H. (1999). Early Dynastic Egypt. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415260116.

- Engels, D.W. (2001). Classical Cats. The Rise and Fall of the Sacred Cat. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415261627.

- Apostola, E. (2014). "Cross-cultural Relations between Egypt and Greece during the Early Iron Age: Representations of Egyptian Lion-Headed Deities in the Aegean". In Pinarello, M.S.; Yoo, J.; Lundock, J.; Walsh, C. (eds.). Current Research in Egyptology: Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual Symposium. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 100–112.

- Boessneck, J., von den Driesch, A. (1990). "Die Tierknochenfunde". In Dreyer, G. (ed.). Umm el-Qaab: Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof. 3./4. Vorbericht. Abteilung Kairo. Berlin: 46. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Callou, C.; Samzun, A.; Zivie, A. (2004). "A lion found in the Egyptian tomb of Maïa". Nature. 427 (6971): 211–212. doi:10.1038/427211a. PMID 14724625. S2CID 4422033.

- Samzun, A.; Hennet, P.; Lichtenberg, R.; Callou, C.; Zivie, A. (2011). "Le lion du Bubasteion à Saqqara (Égypte)". Anthropozoologica. 46 (2): 63–84. doi:10.5252/az2011n2a4. S2CID 129186181.

- Sparreboom, A. (2016). "Chapter 2: Procuring beasts for hunting spectacles". Venationes Africanae: Hunting spectacles in Roman North Africa: cultural significance and social function. Amsterdam: Amsterdam School of Historical Studies. pp. 67–98. ISBN 9789463320238.

- Chambers, Delaney (29 January 2017). "150-year-old Diorama Surprises Scientists With Human Remains". news.nationalgeographic.com. National Geographic. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

External links

- Marks, T. (2018). "'I find myself making growling noises while I'm painting' – an interview with Walton Ford, who painted Barbary lions". Apollo Magazine.

- Babas, L. (2018). "History : When London's very first zoo housed Morocco's Atlas Lions". Yabiladi.

- Moroccan 'Atlas' lion at Parc Sindibad, Casablanca (video).

- Black, S. (2014). "Moroccan lions in zoos today". University of Kent Blog.

- "Barbary Lion Information". Being Lion.