Belgrade Zoo

Beo zoo vrt (Serbian: Бео зоо врт), also known as Vrt dobre nade (Garden of good hope), is a zoo located in Kalemegdan Park, downtown of Belgrade, Serbia. Founded on July, 12 1936, it is considered to be one of the oldest public zoos in southeastern Europe.[1] The zoo covers 7 hectares (17 acres) and it houses a collection of approximately 150 animal species, with close to 2,000 individuals, making it the largest collection in Serbia.[2] It's also recognized as one of the most visited tourist attractions in Belgrade.[3]

| |

White lion, zoo's big attraction | |

| Date opened | 12 July 1936 |

|---|---|

| Location | Kalemegdan Park, Belgrade, Serbia |

| Coordinates | 44°49′33″N 20°27′12″E |

| Land area | 7 hectares (17 acres) |

| No. of animals | +1700 |

| No. of species | +150 |

| Annual visitors | +420,000 (2018) |

| Director | Srboljub Aleksić |

| Website | www |

Belgrade zoo officially applied for EAZA membership in 2017.

History

During the Austrian occupation of northern Serbia from 1717 to 1739, they conducted extensive project of rebuilding Belgrade, turning the city into Westernized European, baroque-style town. This period is today referred to as the Baroque Belgrade.[4] The governor in this period, Charles Alexander, Duke of Württemberg, ordered the construction of Württemberg Palace, a massive building used as his seat, which was located at the modern Republic Square area. There, he formed something of the first zoo in Belgrade. He ordered his soldiers to capture and bring to him "wild beasts from the forests and mountains of Serbia", which he then kept in cages. The Austrians withdrew in 1739 and the Ottomans demolished the building in 1743.[5]

The present Belgrade Zoological Garden was officially opened on 12 July 1936 by the mayor of Belgrade, Vlada Ilić. The zoo was initially no larger than 3.5 hectares (8.6 acres), but was eventually expanded to about 14 hectares. It quickly became one of the most popular places with the locals and even members of the Karađorđević dynasty, who were regulars at the zoo.[2] In the beginning, animals were acquired through personal donations. First group of animals was purchased by mayor Ilić himself while the first manager, Aleksandar Krstić, purchased the first hippopotamus in 1937 to celebrate the birth iof his son.[6]

During the Second World War, the zoo was bombed twice, by the Nazis in 1941 and by the Allies in 1944, heavily damaging the infrastructure and killing most of the animals. The zoo also lost seven hectares of land.[2] The 1941 bombing of the zoo was described in Winston Churchill's The Second World War and Emir Kusturica's 1995 film Underground. Miodrag Savković, manager of the zoo during the World War II occupation, was arrested right away by the new Communist authorities, and shot, even though the charges against him nor his resting place are known.[6]

The zoo recovered over time but again faced tough times in the eighties. Animals were neglected and living in bad conditions. In 1984 the zoo received a pair of black rhinoceroses as a gift from the Prime Minister Robert Mugabe and the country of Zimbabwe. Unfortunately, they lived for just a couple of months due to bad care and lack of knowledge about this species. In 1989 Muammar Gaddafi also gave six of his Arabian camels.[7] The government, under the pressure of real estate groups also unsuccessfully tried to appropriate the space to build luxurious hotels, casinos and nightclubs.[2] Belgrade zoo was preserved thank to efforts from sculptor Vuk Bojović, who served as the zoo's director between May 1, 1986 and his death on September 17, 2014. He received substantial recognition for his work through out the region. Bojović made various improvements to the living conditions of animals, brought numerous new species to the animal collection - most notably great apes, white tigers, and lions - changed the zoo's bad management, and made it a profitable business.

During the tenure of mayor Dragan Đilas (2008–13), the idea of expanding the zoo to Donji Grad, which it occupied prior to the World War II, resurfaced, but the experts and Bojović himself were against it. The urban plan for the fortress from 1965 already projected the complete relocation of the zoo outside of the fortress, on some of the suburban locations, which in later plans included Veliko Blato, Stepin Lug or Jelezovac. The expansion of the zoo would block the pedestrian pathways between the Danube's and Sava's parts of the fortress, which had been blocked in 1949 but then restored in 2009 with the reconstruction and opening of the Sava Gate. Also, it would prevent the exploration of Donji Grad, which is still largely unexplored and leave the Gate of Charles VI, a masterpiece of Balthasar Neumann, within the zoo itself. By 2017, the zoo had not relocated and the idea of expansion was dropped.[8]

Animals and exhibits

Belgrade zoo holds more than 1,700 animals of around 150 species. One of its biggest attractions are albino and white animals, which were collected by the former director Vuk Bojović.[9] In 2005, Belgrade zoo received white lions from Kruger National Park and since then has managed to successfully breed these animals.[9] In 2007, Belgrade also became the only city in Europe to house a white buffalo. In June 2018, a white buffalo calf was born.[10] A pair of white tigers can be seen at the zoo as well.[11]

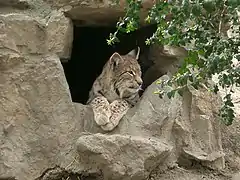

The zoo is also active in conservation and species-preservation efforts of the endangered local fauna such as Balkan lynx and bearded vulture. In September 2018, the zoo reintroduced its first griffon vulture to the wild.

In late May of 2019, the zoo opened its penguinarium for seventeen newly arrived Humboldt penguins, which was the first time in thirty years that these birds were on a display in Belgrade.[12][3]

Other notable animal species in Belgrade zoo include:

- Mammals such as red kangaroo, Parma wallaby, Asian elephant, Barbary macaque, silvery marmoset, Bornean orangutan, common chimpanzee, ring-tailed lemur, hippopotamus, Rothschild's giraffe, Bactrian camel, llama, alpaca, American bison, yak, dorcas gazelle, eland, red deer, fallow deer, reindeer, Himalayan thar, Siberian ibex, Barbary sheep, muflon, Grant's zebra, Brazilian tapir, capybara, Indian crested porcupine, Patagonian mara, spotted hyena, binturong, raccoon, white-nosed coati, jaguar, cheetah, serval, jungle cat, Arctic wolf, fennec fox, meerkat, honey badger, Oriental small-clawed otter, polar bear, Cape fur seal and harbor seal

- Birds such as ostrich, southern cassowary, emu, rhea, southern screamer, southern ground hornbill, trumpeter hornbill, black-necked aracari, burrowing parrot, grey parrot, red-and-green macaw, blue-and-yellow macaw, white-throated toucan, marabou stork, black swan, white spoonbill, greater flamingo, several species of pheasant, guineafowl, Eurasian eagle-owl, white-tailed eagle, Steller's sea eagle, bearded vulture and Andean condor

- Reptiles such as Cuban crocodile, spectacled caiman, leopard tortoise, rock monitor, Nile monitor, green iguana, boa constrictor, green anaconda, Burmese python, boa constrictor, emerald tree boa

Hippopotamus mother with a calf

Hippopotamus mother with a calf

Notable animals

Throughout its history, the zoo has had several residents, well known for their scientific importance or for being beloved by the public.

Sami the chimpanzee was the first great ape to be displayed in the zoo. He received widespread public attention when he escaped from his cage just a month following his arrival in 1988. After an hour of wandering through Belgrade's downtown streets, Sami was calmed down by the zoo's manager, Vuk Bojović, who then placed him in his personal car and drove him back to his cage. The ape managed to escape again, just two days later, but was this time caught by using a tranquilizer gun.

Gabi was a German shepherd that saved her partner, a night guard, from an escaped jaguar. Though she was seriously wounded during the fight with the feline, she eventually recovered and continued her night guard duty.

Muja is considered to be the world's oldest living alligator. He was transferred to Belgrade as an adult from an undocumented zoo in Germany in 1937.

See also

References

- "Zoološki vrt". City of Belgrade. www.belgrade.rs. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- "History". Belgrade Zoo. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- "Vesić: Pingvinarijum je veliki događaj za Beo zoo vrt i svu našu decu". beograd.rs (in Serbian). 15 March 2019.

- Milica Dimitrijević (18 April 2019). "Izgradnja baroknog Beograda" [Construction of Baroque Belgrade]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- Branka Vasiljević (17 August 2020). "Kompjuter otkriva tajne Virtembergove palate" [Computer unveils secrets of Württemberg Palace]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- Miloš Lazić (12 July 2020). Нилски коњ као рођендански поклон [Hippopotamus as birthday gift]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1189 (in Serbian). pp. 26–27.

- "Vrt kojim se Beograđani ponose" (in Serbian).

- Daliborka Mučibabić (13 April 2014), "Od vrha Sahat kule do dna Rimskog bunara", Politika (in Serbian)

- "Zašto se baš u beogradskom zoološkom vrt radjaju veoma retke bele životinje" (in Serbian). Blic. 30 May 2018.

- "N1 u Beo zoo vrtu: Bizon Dušanka atrakcija, stižu i pingvini" (in Serbian). N1. 4 June 2018.

- "Upoznajte belog bengalskog tigra Tomeka" (in Serbian). Blic. 24 July 2018.

- "Radojčić: Beograd dobio dečji zoo vrt na hiljadu kvadrata" (in Serbian). Danas. 15 March 2019.