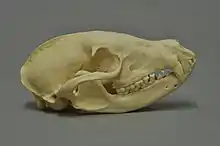

White-nosed coati

The white-nosed coati (Nasua narica),[2] also known as the coatimundi (/koʊˌɑːtɪˈmʌndi/),[3][4] is a species of coati and a member of the family Procyonidae (raccoons and their relatives). Local Spanish names for the species include pizote, antoon, and tejón, depending upon the region.[5] It weighs about 4–6 kg (8.8–13.2 lb).[6] However, males are much larger than females: small females can weigh as little as 2.5 kg (5.5 lb), while large males can weigh as much as 12.2 kg (27 lb).[7][8] On average, the nose-to-tail length of the species is about 110 cm (3.6 ft) with about half of that being the tail length.

| White-nosed coati | |

|---|---|

| |

| in Costa Rica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Procyonidae |

| Genus: | Nasua |

| Species: | N. narica |

| Binomial name | |

| Nasua narica (Linnaeus, 1766) | |

| Subspecies[2] | |

| |

| |

| The native range of the white-nosed coati. Note: Its Colombian range is restricted to the far northwest (see text). | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Viverra narica (Linnaeus, 1766) | |

Habitat and range

White-nosed coatis inhabit wooded areas (dry and moist forests) of the Americas. They are found at any altitude from sea level to 3,000 m (9,800 ft),[9] and from as far north as southeastern Arizona and New Mexico, through Mexico and Central America, to far northwestern Colombia (Gulf of Urabá region, near Colombian border with Panama).[10][11] There has been considerable confusion over its southern range limit,[12] but specimen records from most of Colombia (only exception is far northwest) and Ecuador are all South American coatis.[10][11]

Coatis from Cozumel Island have been treated as a separate species, the Cozumel Island coati, but the vast majority of recent authorities treat it as a subspecies, N. narica nelsoni, of the white-nosed coati.[2][1][9][13] They are smaller than white-nosed coatis from the adjacent mainland (N. n. yucatanica), but when compared more widely to white-nosed coatis the difference in size is not as clear.[10] The level of other differences also support its status as a subspecies rather than separate species.[10]

White-nosed coatis have also been found in the U.S. state of Florida, where they are an introduced species. It is unknown precisely when introduction occurred; an early specimen in the Florida Museum of Natural History, labeled an "escaped captive", dates to 1928. There are several later documented cases of coatis escaping captivity, and since the 1970s there have been a number of sightings, and several live and dead specimens of various ages have been found. These reports have occurred over a wide area of southern Florida, and there is probable evidence of breeding, indicating that the population is well established.[14]

Feeding habits

They are omnivores, preferring small vertebrates, fruits, carrion, insects, snakes, and eggs. They can climb trees easily, where the tail is used for balance, but they are most often on the ground foraging. Their predators include boas, raptors, cats, and tayras (Eira barbara). They readily adapt to human presence; like raccoons, they will raid campsites and trash receptacles. They can be tamed easily, and have been verified experimentally to be quite intelligent.

Behavior

While the raccoon and ringtail are nocturnal, coatis are active by day, retiring during the night to a specific tree and descending at dawn to begin their daily search for food. However, their habits are adjustable, and in areas where they are hunted by humans for food, or where they raid human settlements for their own food, they might become more nocturnal. Adult males are solitary, but females and sexually immature males form social groups. They use many vocal signals to communicate with one another, and also spend time grooming themselves and each other with their teeth and claws. During foraging times, the young cubs are left with a pair of babysitters, similar to meerkats. The young males and even some females tend to play-fight. Many of the coatis will have short fights over food.

White-nosed coatis are known pollinators of the balsa tree, as observed in a study of a white-nosed coati population in Costa Rica.[15] The coati were observed inserting their noses into the flowers of the tree and ingesting nectar, while the flower showed no subsequent signs of damage. Pollen from the flowers covers the face of the coati following feeding, and later disseminates through the surrounding forest following detachment. Scientists observed a dependent relationship between the balsa tree, which provides a critical resource of hydration and nutrition to the white-nosed coati when environment resources are scarce, and the coati, which increases proliferation of the tree through pollination.

References

- Cuarón, A. D., Helgen, K., Reid, F., Pino, J. & González-Maya, J. F. (2016). "Nasua narica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T41683A45216060.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- Animal Diversity Web at University of Michigan. "Coatis are also referred to in some texts as coatimundis. The name coati or coatimundi is Tupian Indian in origin."

- "Tejón", which means badger, is mainly used in Mexico.

- David J. Schmidly; William B. Davis (1 August 2004). The mammals of Texas. University of Texas Press. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-0-292-70241-7. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- North American Mammals: Nasua narica. Mnh.si.edu. Retrieved on 2011-09-15.

- Coati (Nasua narica). Wc.pima.edu. Retrieved on 2011-09-15.

- Reid, Fiona A. (1997). A Field Guide to the Mammals of Central America and Southeast Mexico. pp. 259–260. ISBN 0-19-506400-3. OCLC 34633350.

- Decker, D. M. (1991). Systematics Of The Coatis, Genus Nasua (Mammalia, Procyonidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 104: 370–386

- Guzman-Lenis, A. R. (2004). Preliminary Review of the Procyonidae in Colombia. Acta Biológica Colombiana 9(1): 69–76

- Eisenberg, J., and K. H. Redford (1999). Mammals of the Neotropcs: The Central Neotropics. Vol. 3, p. 288. ISBN 0-226-19541-4

- Kays, R. (2009). White-nosed Coati (Nasua narica), pp. 527–528 in: Wilson, D. E., and R. A. Mittermeier, eds. (2009). Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 1, Carnivores. ISBN 978-84-96553-49-1

- Simberloff, Daniel; Don C. Schmitz; Tom C. Brown (1997). Strangers in Paradise: Impact and Management of Nonindigenous Species in Florida. Island Press. p. 170. ISBN 1-55963-430-8. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- Mora, José Manuel. (1999). White-nosed coati Nasua narica (Carnivora: Procyonidae) as a potentialpollinator of Ochroma pyramidale (Bombacaceae). Revista de Biología Tropical 47(4):719-721

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nasua narica. |