Bengal tiger

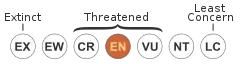

The Bengal tiger is a tiger from a specific population of the Panthera tigris tigris subspecies that is native to the Indian subcontinent.[3] It is threatened by poaching, loss, and fragmentation of habitat, and was estimated at comprising fewer than 2,500 wild individuals by 2011. None of the Tiger Conservation Landscapes within its range is considered large enough to support an effective population of more than 250 adult individuals.[1] India's tiger population was estimated at 1,706–1,909 individuals in 2010.[4] By 2018, the population had increased to an estimated 2,603–3,346 individuals.[5] Around 300–500 tigers are estimated in Bangladesh, 220–274 tigers in Nepal and 103 tigers in Bhutan.[1][6][7]

| Bengal tiger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male in Kanha Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh, India | |

_female_3_crop.jpg.webp) | |

| Bengal tigress in Kanha Tiger Reserve | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. t. tigris |

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera tigris tigris | |

| |

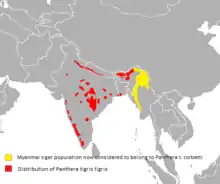

| Range of Bengal tiger in red | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The tiger is estimated to be present in the Indian subcontinent since the Late Pleistocene, for about 12,000 to 16,500 years.[8][9][10]

The Bengal tiger ranks among the biggest wild cats alive today.[2][11] It is considered to belong to the world's charismatic megafauna.[12] It is the national animal of both India and Bangladesh.[13] It used to be called Royal Bengal tiger.[14]

Taxonomy

Felis tigris was the scientific name used by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 for the tiger.[15] It was subordinated to the genus Panthera by Reginald Innes Pocock in 1929. Bengal is the traditional type locality of the species and the nominate subspecies Panthera tigris tigris.[16]

The validity of several tiger subspecies in continental Asia was questioned in 1999. Morphologically, tigers from different regions vary little, and gene flow between populations in those regions is considered to have been possible during the Pleistocene. Therefore, it was proposed to recognise only two subspecies as valid, namely P. t. tigris in mainland Asia, and P. t. sondaica in the Greater Sunda Islands and possibly in Sundaland.[17] The nominate subspecies P. t. tigris constitutes two clades: the northern clade comprises the Siberian and Caspian tiger populations, and the southern clade all remaining continental tiger populations.[18] The extinct and living tiger populations in continental Asia have been subsumed to P. t. tigris since the revision of felid taxonomy in 2017.[3]

Results of a genetic analysis of 32 tiger samples indicate that the Bengal tiger samples grouped into a different monophyletic clade than the Siberian tiger samples.[19]

Genetic ancestry

The Bengal tiger is defined by three distinct mitochondrial nucleotide sites and 12 unique microsatellite alleles. The pattern of genetic variation in the Bengal tiger corresponds to the premise that it arrived in India approximately 12,000 years ago.[20] This is consistent with the lack of tiger fossils from the Indian subcontinent prior to the late Pleistocene, and the absence of tigers from Sri Lanka, which was separated from the subcontinent by rising sea levels in the early Holocene.[9]

Characteristics

_Ranthambhore_India_12.10.2014.jpg.webp)

The Bengal tiger's coat is yellow to light orange, with stripes ranging from dark brown to black; the belly and the interior parts of the limbs are white, and the tail is orange with black rings. The white tiger is a recessive mutant of the tiger, which is reported in the wild from time to time in Assam, Bengal, Bihar, and especially from the former State of Rewa. However, it is not to be mistaken as an occurrence of albinism. In fact, there is only one fully authenticated case of a true albino tiger, and none of black tigers, with the possible exception of one dead specimen examined in Chittagong in 1846.[21]

Males and females have an average total length of 270 to 310 cm (110 to 120 in) and 240 to 265 cm (94 to 104 in) respectively, including a tail of 85 to 110 cm (33 to 43 in) long.[2][22] They typically range 90 to 110 cm (35 to 43 in) in height at the shoulders.[22] The standard weight of males ranges from 175 to 260 kg (386 to 573 lb), while that of the females ranges from 100 to 160 kg (220 to 350 lb).[2][22] The smallest recorded weights for Bengal tigers are from the Bangladesh Sundarbans, where adult females are 75 to 80 kg (165 to 176 lb).[23]

The tiger has exceptionally stout teeth. Its canines are 7.5 to 10 cm (3.0 to 3.9 in) long and thus the longest among all cats.[24] The greatest length of its skull is 332 to 376 mm (13.1 to 14.8 in).[17]

Body weight

Bengal tigers weigh up to 325 kg (717 lb), and reach a head and body length of 320 cm (130 in).[24] Several scientists indicated that adult male Bengal tigers from the Terai in Nepal and Bhutan, and Assam, Uttarakhand and West Bengal in north India consistently attain more than 227 kg (500 lb) of body weight. Seven adult males captured in Chitwan National Park in the early 1970s had an average weight of 235 kg (518 lb) ranging from 200 to 261 kg (441 to 575 lb), and that of the females was 140 kg (310 lb) ranging from 116 to 164 kg (256 to 362 lb).[25] Thus, the Bengal tiger rivals the Siberian tiger in average weight.[26] In addition, the record for the greatest length of a tiger skull was an "over the bone" length of 16.25 in (413 mm); this tiger was shot in the vicinity of Nagina in northern India.[27]

Three tigresses from the Bangladesh Sundarbans had a mean weight of 76.7 kg (169 lb). The oldest female weighed 75 kg (165 lb) and was in a relatively poor condition at the time of capture. Their skulls and body weights were distinct from those of tigers in other habitats, indicating that they may have adapted to the unique conditions of the mangrove habitat. Their small sizes are probably due to a combination of intense intraspecific competition and small size of prey available to tigers in the Sundarbans, compared to the larger deer and other prey available to tigers in other parts.[28]

Records

Two tigers shot in Kumaon District and near Oude at the end of the 19th century allegedly measured more than 12 ft (366 cm). But at the time, sportsmen had not yet adopted a standard system of measurement; some measured 'between the pegs' while others measured 'over the curves'.[29] In the beginning of the 20th century, a male tiger was shot in central India with a head and body length of 221 cm (87 in) between pegs, a chest girth of 150 cm (59 in), a shoulder height of 109 cm (43 in) and a tail length of 81 cm (32 in), which was perhaps bitten off by a rival male. This specimen could not be weighed, but it was calculated to weigh no less than 272 kg (600 lb).[30] A male weighing 259 kg (570 lb) was shot in northern India in the 1930s.[27] In 1980 and 1984, scientists captured and tagged two male tigers in Chitwan National Park that weighed more than 270 kg (595 lb).[31] The heaviest wild tiger was possibly a huge male killed in 1967 at the foothills of the Himalayas. It weighed 388.7 kg (857 lb) after eating a buffalo calf, and measured 323 cm (127 in) in total length between pegs, and 338 cm (133 in) over curves. Without eating the calf beforehand, it would have likely weighed at least 324.3 kilograms (715 lb). This specimen is on exhibition in the Mammals Hall of the Smithsonian Institution.[32]

Distribution and habitat

In 1982, a sub-fossil right middle phalanx was found in a prehistoric midden near Kuruwita in Sri Lanka, which is dated to about 16,500 ybp and tentatively considered to be of a tiger. Tigers appear to have arrived in Sri Lanka during a pluvial period, during which sea levels were depressed, evidently prior to the last glacial maximum about 20,000 years ago.[33] The tiger probably arrived too late in southern India to colonise Sri Lanka, which earlier had been connected to India by a land bridge.[16]

Results of a phylogeographic study using 134 samples from tigers across the global range suggest that the historical northeastern distribution limit of the Bengal tiger is the region in the Chittagong Hills and Brahmaputra River basin, bordering the historical range of the Indochinese tiger.[9][34] In the Indian subcontinent, tigers inhabit tropical moist evergreen forests, tropical dry forests, tropical and subtropical moist deciduous forests, mangroves, subtropical and temperate upland forests, and alluvial grasslands. Latter habitat once covered a huge swath of grassland, riverine and moist semi-deciduous forests along the major river system of the Gangetic and Brahmaputra plains, but has now been largely converted to agricultural land or severely degraded. Today, the best examples of this habitat type are limited to a few blocks at the base of the outer foothills of the Himalayas including the Tiger Conservation Units (TCUs) Rajaji-Corbett, Bardia-Banke, and the transboundary TCUs Chitwan-Parsa-Valmiki, Dudhwa-Kailali and Shuklaphanta-Kishanpur. Tiger densities in these TCUs are high, in part because of the extraordinary biomass of ungulate prey.[35]

The tigers in the Sundarbans in India and Bangladesh are the only ones in the world inhabiting mangrove forests.[4] The population in the Indian Sundarbans was estimated as 86-90 individuals in 2018.[5]

India

In the 20th century, Indian censuses of wild tigers relied on the individual identification of footprints known as pug marks – a method that has been criticised as deficient and inaccurate. Camera traps are now being used in many sites.[36]

Good tiger habitats in subtropical and temperate forests include the Tiger Conservation Units (TCUs) Manas-Namdapha. TCUs in tropical dry forest include Hazaribag Wildlife Sanctuary, Nagarjunsagar-Srisailam Tiger Reserve, Kanha-Indravati corridor, Orissa dry forests, Panna National Park, Melghat Tiger Reserve and Ratapani Tiger Reserve. The TCUs in tropical moist deciduous forest are probably some of the most productive habitats for tigers and their prey, and include Kaziranga-Meghalaya, Kanha-Pench, Simlipal and Indravati Tiger Reserves. The TCUs in tropical moist evergreen forests represent the less common tiger habitats, being largely limited to the upland areas and wetter parts of the Western Ghats, and include the tiger reserves of Periyar, Kalakad-Mundathurai, Bandipur and Parambikulam Wildlife Sanctuary.[35]

During a tiger census in 2008, camera trap and sign surveys using GIS were employed to estimate site-specific densities of tiger, co-predators and prey. Based on the result of these surveys, the total tiger population was estimated at 1,411 individuals ranging from 1,165 to 1,657 adult and sub-adult tigers of more than 1.5 years of age. Across India, six landscape complexes were surveyed that host tigers and have the potential to be connected. These landscapes comprise the following:[37]

- in the Sivaliks–Gangetic flood plain landscape there are six populations with an estimated population size of 259 to 335 individuals in an area of 5,080 km2 (1,960 sq mi) of forested habitats, which are located in Rajaji and Corbett National Parks, in the connected habitats of Dudhwa-Kheri-Pilibhit, in Suhelwa Tiger Reserve, in Sohagi Barwa Sanctuary and in Valmiki National Park;

- in the Central Indian highlands there are 17 populations with an estimated population size of 437 to 661 individuals in an area of 48,610 km2 (18,770 sq mi) of forested habitats, which are located in the landscapes of Kanha-Pench, Satpura-Melghat, Sanjay-Palamau, Navegaon-Indravati; isolated populations are supported in the tiger reserves of Bandhavgarh, Tadoba, Simlipal and the national parks of Panna, Ranthambore–Kuno–Palpur–Madhav and Saranda;

- in the Eastern Ghats landscape there is a single population with an estimated population size of 49 to 57 individuals in a 7,772 km2 (3,001 sq mi) habitat in three separate forest blocks located in the Srivenkateshwara National Park, Nagarjunasagar Tiger Reserve and the adjacent proposed Gundla Brahmeshwara National Park, and forest patches in the tehsils of Kanigiri, Badvel, Udayagiri and Giddalur;

- in the Western Ghats landscape there are seven populations with an estimated population size of 336 to 487 individuals in a forested area of 21,435 km2 (8,276 sq mi) in three major landscape units Periyar-Kalakad-Mundathurai, Bandipur-Parambikulam-Sathyamangalam-Mudumalai-Anamalai-Mukurthi and Anshi-Kudremukh-Dandeli;

- in the Brahmaputra flood plains and northeastern hills tigers live in an area of 4,230 km2 (1,630 sq mi) in several patchy and fragmented forests;

- in the Sundarbans National Park tigers live in about 1,586 km2 (612 sq mi) of mangrove forest.

Ranthambore National Park hosts India's westernmost tiger population.[38] The Dangs' Forest in southeastern Gujarat is potential tiger habitat.[4]

As of 2014, the Indian tiger population was estimated to range over an area of 89,164 km2 (34,426 sq mi) and number 2,226 adult and subadult tigers older than one year. About 585 tigers were present in the Western Ghats, where Radhanagari and Sahyadri Tiger Reserves were newly established. The largest population resided in Corbett Tiger Reserve with about 215 tigers. The Central Indian tiger population is fragmented and depends on wildlife corridors that facilitate connectivity between protected areas.[39]

In May 2018, a tiger was recorded in Sahyadri Tiger Reserve for the first time in eight years.[40] In February 2019, a tiger was sighted in Gujarat's Lunavada area in Mahisagar district, and found dead shortly afterwards.[41][42] Officials assumed that it originated in Ratapani Tiger Reserve and travelled about 300 km (190 mi) over two years. It probably died of starvation. In May 2019, camera traps recorded tigers in Mhadei Wildlife Sanctuary and Bhagwan Mahaveer Sanctuary and Mollem National Park, the first records in Goa since 2013.[43][44]

Bangladesh

Tigers in Bangladesh are now relegated to the forests of the Sundarbans and the Chittagong Hill Tracts.[45] The Chittagong forest is contiguous with tiger habitat in India and Myanmar, but the tiger population is of unknown status.[46]

As of 2004, population estimates in Bangladesh ranged from 200 to 419 individuals, most of them in the Sundarbans.[45] This region is the only mangrove habitat in this bioregion, where tigers survive, swimming between islands in the delta to hunt prey.[35] Bangladesh's Forest Department is raising mangrove plantations supplying forage for spotted deer. Since 2001, afforestation has continued on a small scale in newly accreted lands and islands of the Sundarbans.[47] From October 2005 to January 2007, the first camera trap survey was conducted across six sites in the Bangladesh Sundarbans to estimate tiger population density. The average of these six sites provided an estimate of 3.7 tigers per 100 km2 (39 sq mi). Since the Bangladesh Sundarbans is an area of 5,770 km2 (2,230 sq mi) it was inferred that the total tiger population comprised approximately 200 individuals.[48] In another study, home ranges of adult female tigers were recorded comprising between 12 and 14 km2 (4.6 and 5.4 sq mi), which would indicate an approximate carrying capacity of 150 adult females.[23][49] The small home range of adult female tigers (and consequent high density of tigers) in this habitat type relative to other areas may be related to both the high density of prey and the small size of the Sundarban tigers.[23]

Since 2007 tiger monitoring surveys have been carried out every year by WildTeam in the Bangladesh Sundarbans to monitor changes in the Bangladesh tiger population and assess the effectiveness of conservation actions. This survey measures changes in the frequency of tiger track sets along the sides of tidal waterways as an index of relative tiger abundance across the Sundarbans landscape.[50]

By 2009, the tiger population in the Bangladesh Sundarbans was estimated as 100–150 adult females or 335–500 tigers overall. Female home ranges, recorded using Global Positioning System collars, were some of the smallest recorded for tigers, indicating that the Bangladesh Sundarbans could have one of the highest densities and largest populations of tigers anywhere in the world. They are isolated from the next tiger population by a distance of up to 300 km (190 mi). Information is lacking on many aspects of Sundarbans tiger ecology, including relative abundance, population status, spatial dynamics, habitat selection, life history characteristics, taxonomy, genetics, and disease. There is also no monitoring program in place to track changes in the tiger population over time, and therefore no way of measuring the response of the population to conservation activities or threats. Most studies have focused on the tiger-human conflict in the area, but two studies in the Sundarbans East Wildlife sanctuary documented habitat-use patterns of tigers, and abundances of tiger prey, and another study investigated tiger parasite load. Some major threats to tigers have been identified. The tigers living in the Sundarbans are threatened by habitat destruction, prey depletion, highly aggressive and rampant intraspecific competition, tiger-human conflict, and direct tiger loss.[28] By 2017, this population was estimated at 84–158 individuals.[51] A rising sea-level due to climate change is projected to cause a severe loss of suitable habitat for this population in the following decades, around 50% by 2050 and 100% by 2070.[52]

Nepal

.jpg.webp)

The tiger population in the Terai of Nepal is split into three isolated subpopulations that are separated by cultivation and densely settled habitat. The largest population lives in Chitwan National Park and in the adjacent Parsa National Park encompassing an area of 2,543 km2 (982 sq mi) of prime lowland forest. To the west, the Chitwan population is isolated from the one in Bardia National Park and adjacent unprotected habitat farther west, extending to within 15 km (9.3 mi) of the Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserve, which harbours the smallest population.[53]

From February to June 2013, a camera trapping survey was carried out in the Terai Arc Landscape, across an area of 4,841 km2 (1,869 sq mi) in 14 districts. The country's tiger population was estimated at 163–235 breeding adults comprising 102–152 tigers in the Chitwan-Parsa protected areas, 48–62 in Bardia-Banke National Parks and 13–21 in Shuklaphanta National Park.[54] Between November 2017 and April 2018, the third nationwide survey for tiger and prey was conducted in the Terai Arc Landscape; the country's population was estimated at 220–274 tigers.[6]

Bhutan

In Bhutan, tigers have been documented in 17 of 18 districts. They inhabit the subtropical Himalayan foothills at an elevation of 200 m (660 ft) in the south to over 3,000 m (9,800 ft) in the temperate forests in the north. Their stronghold appears to be the country's central belt between the Mo River in the west and the Kulong River in the east ranging in elevation from 2,000 to 3,500 m (6,600 to 11,500 ft).[55] Royal Manas and Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Parks form the largest contiguous tiger conservation area in Bhutan representing subtropical to alpine habitat types.[56] In 2010, camera traps recorded a tiger pair at elevations of 3,000 to 4,100 m (9,800 to 13,500 ft). As of 2015, the tiger population in Bhutan was estimated at 89 to 124 individuals in a survey area of 28,225 km2 (10,898 sq mi).[57]

In 2008, a tiger was recorded at an elevation of 4,200 m (13,800 ft) in Jigme Dorji National Park, which is the highest altitudinal record of a tiger known to date.[58] In 2017, a tiger was recorded for the time in Bumdeling Wildlife Sanctuary. It probably used a wildlife corridor to reach northeastern Bhutan.[59]

Ecology and behaviour

_-_Koshyk.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The basic social unit of the tiger is the elemental one of female and her offspring. Adult animals congregate only temporarily when special conditions permit, such as plenty supply of food. Otherwise, they lead solitary lives, hunting individually for the forest and grassland animals, upon which they prey. Resident adults of either sex maintain home ranges, confining their movements to definite habitats within which they satisfy their needs and those of their cubs, which includes prey, water and shelter. In this site, they also maintain contact with other tigers, especially those of the opposite sex. Those sharing the same ground are well aware of each other's movements and activities.[21] In Chitwan National Park, radio-collared subadult tigers started dispersing from their natal areas earliest at the age of 19 months. Four females stayed closer to their mother's home range than 10 males. Latter dispersed between 9.5 and 65.7 km (5.9 and 40.8 mi). None of them crossed open cultivated areas that were more than 10 km (6.2 mi) wide, but moved through prime alluvial and forested habitat.[60]

In the Panna Tiger Reserve an adult radio-collared male tiger moved 1.7 to 10.5 km (1.1 to 6.5 mi) between locations on successive days in winter, and 1 to 13.9 km (0.62 to 8.64 mi) in summer. His home range was about 200 km2 (77 sq mi) in summer and 110 km2 (42 sq mi) in winter. Included in his home range were the much smaller home ranges of two females, a tigress with cubs and a subadult tigress. They occupied home ranges of 16 to 31 km2 (6.2 to 12.0 sq mi).[61]

The home ranges occupied by adult male residents tend to be mutually exclusive, even though one of these residents may tolerate a transient or sub-adult male at least for a time. A male tiger keeps a large territory in order to include the home ranges of several females within its bounds, so that he may maintain mating rights with them. Spacing among females is less complete. Typically there is partial overlap with neighboring female residents. They tend to have core areas, which are more exclusive, at least for most of the time. Home ranges of both males and females are not stable. The shift or alteration of a home range by one animal is correlated with a shift of another. Shifts from less suitable habitat to better ones are made by animals that are already resident. New animals become residents only as vacancies occur when a former resident moves out or dies. There are more places for resident females than for resident males.[21]

During seven years of camera trapping, tracking, and observational data in Chitwan National Park, 6 to 9 breeding tigers, 2 to 16 non-breeding tigers, and 6 to 20 young tigers of less than one year of age were detected in the study area of 100 km2 (39 sq mi). One of the resident females left her territory to one of her female offspring and took over an adjoining area by displacing another female; and a displaced female managed to re-establish herself in a neighboring territory made vacant by the death of the resident. Of 11 resident females, 7 were still alive at the end of the study period, 2 disappeared after losing their territories to rivals, and 2 died. The initial loss of two resident males and subsequent take over of their home ranges by new males caused social instability for two years. Of 4 resident males, 1 was still alive and 3 were displaced by rivals. Five litters of cubs were killed by infanticide, 2 litters died because they were too young to fend for themselves when their mothers died. One juvenile tiger was presumed dead after being photographed with severe injuries from a deer snare. The remaining young lived long enough to reach dispersal age, 2 of them becoming residents in the study area.[62]

Hunting and diet

The tiger is a carnivore. It prefers hunting large ungulates such as chital, sambar, gaur, and to a lesser extent also barasingha, water buffalo, nilgai, serow and takin. Among the medium-sized prey species it frequently kills wild boar, and occasionally hog deer, Indian muntjac and grey langur. Small prey species such as porcupines, hares and peafowl form a very small part in its diet. Because of the encroachment of humans into tiger habitat, it also preys on domestic livestock.[63][64][65][66][67]

Bengal tigers occasionally hunt and kill predators such as Indian leopard, Indian wolf, Indian jackal, fox, mugger crocodile, Asiatic black bear, sloth bear, and dhole. They rarely attack adult Indian elephant and Indian rhinoceros, but such extraordinarily rare events have been recorded.[2] In Kaziranga National Park, tigers killed 20 rhinoceros in 2007.[68] In 2011 and 2014, two instances were recorded of Bengal tigers killing adult elephants; one in Jim Corbett National Park on a 20-year-old elephant, and another on a 28-year-old elephant in Kaziranga National Park which was killed and eaten by several tigers at once.[69] In the Sundarbans, a king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) and an Indian cobra (Naja naja) were found in the stomachs of tigers.[14]

Results of scat analyses indicate that the tigers in Nagarahole National Park preferred prey weighing more than 176 kg (388 lb) and that on average tiger prey weighed 91.5 kg (202 lb). The prey species included chital, sambar, wild pig and gaur. Gaur remains were found in 44.8% of all tiger scat samples, sambar remains in 28.6%, wild pig remains in 14.3% and chital remains in 10.4% of all scat samples.[70] In Bandipur National Park, gaur and sambar together also constituted 73% of tiger diet.[64]

In most cases, tigers approach their victim from the side or behind from as close a distance as possible and grasp the prey's throat to kill it. Then they drag the carcass into cover, occasionally over several hundred metres, to consume it. The nature of the tiger's hunting method and prey availability results in a "feast or famine" feeding style: they often consume 18–40 kilograms (40–88 lb) of meat at one time.[2] If injured, old or weak, or regular prey species are becoming scarce, tigers also attack humans and become man-eaters.[71]

Reproduction and lifecycle

The tiger in India has no definite mating and birth seasons. Most young are born in December and April.[30] Young have also been found in March, May, October and November.[72] In the 1960s, certain aspects of tiger behaviour at Kanha National Park indicated that the peak of sexual activity was from November to about February, with some mating probably occurring throughout the year.[73]

Males reach maturity at 4–5 years of age, and females at 3–4 years. A Bengal comes into heat at intervals of about 3–9 weeks, and is receptive for 3–6 days. After a gestation period of 104–106 days, 1–4 cubs are born in a shelter situated in tall grass, thick bush or in caves. Newborn cubs weigh 780 to 1,600 g (1.72 to 3.53 lb) and they have a thick wooly fur that is shed after 3.5–5 months. Their eyes and ears are closed. Their milk teeth start to erupt at about 2–3 weeks after birth, and are slowly replaced by permanent dentition from 8.5–9.5 weeks of age onwards. They suckle for 3–6 months, and begin to eat small amounts of solid food at about 2 months of age. At this time, they follow their mother on her hunting expeditions and begin to take part in hunting at 5–6 months of age. At the age of 2–3 years, they slowly start to separate from the family group and become transient – looking out for an area, where they can establish their own territory. Young males move further away from their mother's territory than young females. Once the family group has split, the mother comes into heat again.[2]

Threats

None of the Tiger Conservation Landscapes within the Bengal tiger range is large enough to support an effective population size of 250 individuals. Habitat losses and the extremely large-scale incidences of poaching are serious threats to the species' survival.[1]

The Forest Rights Act passed by the Indian government in 2006 grants some of India's most impoverished communities the right to own and live in the forests, which likely brings them into conflict with wildlife and under-resourced, under-trained, ill-equipped forest department staff. In the past, evidence showed that humans and tigers cannot co-exist.[74]

Poaching

The most significant immediate threat to the existence of wild tiger populations is the illegal trade in poached skins and body parts between India, Nepal and China. The governments of these countries have failed to implement adequate enforcement response, and wildlife crime remained a low priority in terms of political commitment and investment for years. There are well-organised gangs of professional poachers, who move from place to place and set up camp in vulnerable areas. Skins are rough-cured in the field and handed over to dealers, who send them for further treatment to Indian tanning centres. Buyers choose the skins from dealers or tanneries and smuggle them through a complex interlinking network to markets outside India, mainly in China. Other factors contributing to their loss are urbanisation and revenge killing. Farmers blame tigers for killing cattle and shoot them. Their skins and body parts may however become a part of the illegal trade.[75] In Bangladesh, tigers are killed by professional poachers, local hunters, trappers, pirates and villagers. Each group of people has different motives for killing tigers, ranging from profit, excitement to safety concerns. All groups have access to the Illegal wildlife trade in body parts.[76][77]

The illicit demand for bones and body parts from wild tigers for use in Traditional Chinese medicine is the reason for the unrelenting poaching pressure on tigers on the Indian subcontinent. For at least a thousand years, tiger bones have been an ingredient in traditional medicines that are prescribed as a muscle strengthener and treatment for rheumatism and body pain.[78]

Between 1994 and 2009, the Wildlife Protection Society of India has documented 893 cases of tigers killed in India, which is just a fraction of the actual poaching and trade in tiger parts during those years.[79] In 2004, all the tigers in India's Sariska Tiger Reserve were killed by poachers.[80] In 2007, police in Allahabad raided a meeting of suspected poachers, traders and couriers. One of the arrested persons was the biggest buyer of Indian tiger parts who sold them to Chinese buyers, using women from a nomadic tribe as couriers.[81] In 2009, none of the 24 tigers residing in the Panna Tiger Reserve were left because of excessive poaching.[82] In November 2011, two tigers were found dead in Maharashtra: a male tiger was trapped and killed in a wire snare; a tigress died of electrocution after chewing at an electric cable supplying power to a water pump; another dead tigress found in Kanha Tiger Reserve landscape was suspected to have been poisoned.[83]

Human–tiger conflict

The Indian subcontinent has served as a stage for intense human and tiger confrontations. The region affording habitat where tigers have achieved their highest densities is also one which has housed one of the most concentrated and rapidly expanding human populations. At the beginning of the 19th century tigers were so numerous it seemed to be a question as to whether man or tiger would survive. It became the official policy to encourage the killing of tigers as rapidly as possible, rewards being paid for their destruction in many localities. The United Provinces supported large numbers of tigers in the submontane Terai region, where man-eating had been uncommon. In the latter half of the 19th century, marauding tigers began to take a toll of human life. These animals were pushed into marginal habitat, where tigers had formerly not been known, or where they existed only in very low density, by an expanding population of more vigorous animals that occupied the prime habitat in the lowlands, where there was high prey density and good habitat for reproduction. The dispersers had nowhere else to go, since the prime habitat was bordered in the south by cultivation. They are thought to have followed back the herds of domestic livestock that wintered in the plains when they returned to the hills in the spring, and then being left without prey when the herds dispersed back to their respective villages. These tigers were the old, the young and the disabled. All suffered from some disability, mainly caused either by gunshot wounds or porcupine quills.[84]

In the Sundarbans, 10 out of 13-man-eaters recorded in the 1970s were males, and they accounted for 86% of the victims. These man-eaters have been grouped into the confirmed or dedicated ones who go hunting especially for human prey; and the opportunistic ones, who do not search for humans but will, if they encounter a man, attack, kill and devour him. In areas where opportunistic man-eaters were found, the killing of humans was correlated with their availability, most victims being claimed during the honey gathering season.[85] Tigers in the Sunderbans presumably attacked humans who entered their territories in search of wood, honey or fish, thus causing them to defend their territories. The number of tiger attacks on humans may be higher outside suitable areas for tigers, where numerous humans are present but which contain little wild prey for tigers.[86]

In Nepal, the incidence of man-eating tigers has been only sporadic. In Chitwan National Park no cases were recorded before 1980. In the following few years, 13 people have been killed and eaten in the park and its environs. In the majority of cases, man-eating appeared to have been related to an intra-specific competition among male tigers.[84]

In December 2012, a tiger was shot by the Kerala Forest Department on a coffee plantation on the fringes of the Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary. Chief Wildlife Warden of Kerala ordered the hunt for the animal after mass protests erupted as the tiger had been carrying away livestock. The Forest Department had constituted a special task force to capture the animal with the assistance of a 10-member Special Tiger Protection Force and two trained elephants from the Bandipur Tiger Reserve in Karnataka.[87][88]

Conservation efforts

An area of special interest lies in the "Terai Arc Landscape" in the Himalayan foothills of northern India and southern Nepal, where 11 protected areas composed of dry forest foothills and tall-grass savannas harbour tigers in a 49,000 square kilometres (19,000 sq mi) landscape. The goals are to manage tigers as a single metapopulation, the dispersal of which between core refuges can help maintain genetic, demographic, and ecological integrity, and to ensure that species and habitat conservation becomes mainstreamed into the rural development agenda. In Nepal a community-based tourism model has been developed with a strong emphasis on sharing benefits with local people and on the regeneration of degraded forests. The approach has been successful in reducing poaching, restoring habitats, and creating a local constituency for conservation.[89]

WWF partnered with Leonardo DiCaprio to form a global campaign, "Save Tigers Now", with the ambitious goal of building political, financial and public support to double the wild tiger population by 2022.[90] Save Tigers Now started its campaign in 12 different WWF Tiger priority landscapes, since May 2010.[91]

In India

In 1973, Project Tiger was launched aiming at ensuring a viable tiger population in the country and preserving areas of biological importance as a natural heritage for the people. The project's task force visualised these tiger reserves as breeding nuclei, from which surplus animals would disperse to adjacent forests. The selection of areas for the reserves represented as close as possible the diversity of ecosystems across the tiger's distribution in the country. Funds and commitment were mustered to support the intensive program of habitat protection and rehabilitation under the project. By the late 1980s, the initial nine reserves covering an area of 9,115 square kilometres (3,519 sq mi) had been increased to 15 reserves covering an area of 24,700 square kilometres (9,500 sq mi). More than 1100 tigers were estimated to inhabit the reserves by 1984.[92][93]

Through this initiative the population decline was reversed initially, but has resumed in recent years; India's tiger population decreased from 3,642 in the 1990s to just over 1,400 from 2002 to 2008.[94]

The Indian Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 enables government agencies to take strict measures so as to ensure the conservation of the Bengal tigers. The Wildlife Institute of India estimates showed that tiger numbers had fallen in Madhya Pradesh by 61%, Maharashtra by 57%, and Rajasthan by 40%. The government's first tiger census, conducted under the Project Tiger initiative begun in 1973, counted 1,827 tigers in the country that year. Using that methodology, the government observed a steady population increase, reaching 3,700 tigers in 2002. However, the use of more reliable and independent censusing technology including camera traps for the 2007–2008 all-India census has shown that the numbers were in fact less than half than originally claimed by the Forest Department.[95]

Following the revelation that only 1,411 Bengal tigers existed in the wild in India, down from 3,600 in 2003, the Indian government set up eight new tiger reserves.[96] Because of dwindling tiger numbers, the Indian government has pledged US$153 million to further fund the Project Tiger initiative, set up a Tiger Protection Force to combat poachers, and fund the relocation of up to 200,000 villagers to minimise human-tiger interaction.[97] Indian tiger scientists have called for use of technology in the conservation efforts.[98]

In January 2008, the Government of India launched a dedicated anti-poaching force composed of experts from Indian police, forest officials and various other environmental agencies.[99] Ranthambore National Park is often cited as a major success by Indian officials against poaching.[100]

Kuno-Palpur in Madhya Pradesh was supposed receive Asiatic lions from Gujarat. Since no lion has been transferred from Gujarat to Madhya Pradesh so far, it may be used as a sanctuary for the tiger instead.[101][102]

In captivity

Bengal tigers have been captive bred since 1880 and widely crossed with tigers from other range countries.[103]

In July 1976, Billy Arjan Singh acquired a hand-reared tigress from Twycross Zoo in the United Kingdom, and reintroduced her to the wild in Dudhwa National Park with the permission of India's then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.[104] In the 1990s, some tigers from this area were observed to have the typical appearance of Siberian tigers, namely a large head, pale fur, white complexion, and wide stripes, and were suspected to be Siberian–Bengal tiger hybrids. Tiger hair samples from the national park were analysed using mitochondrial sequence analysis. Results revealed that the tigers in question had a Bengal tiger mitochondrial haplotype indicating that their mother was an Bengal tiger.[105] Skin, hair and blood samples from 71 tigers collected in Indian zoos, in the Indian Museum, Kolkata and including two samples from Dudhwa National Park were used for a microsatellite analysis that revealed that two tigers had alleles in two loci contributed by Bengal and Siberian tigers.[106] However, samples of two hybrid specimens constituted a too small sample base to conclusively assume that Tara was the source of the Siberian tiger genes.[107]

Indian zoos have bred tigers for the first time at the Alipore Zoo in Kolkata. The 1997 International Tiger Studbook lists the global captive population of Bengal tigers at 210 individuals that are all kept in Indian zoos, except for one female in North America. Completion of the Indian Bengal Tiger Studbook is a necessary prerequisite to establishing a captive management program for tigers in India.[108]

In Bangladesh

WildTeam is working with local communities and the Bangladesh Forest Department to reduce human-tiger conflict in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. For over 100 years people, tigers, and livestock have been injured and killed in the conflict; in recent decades up to 50 people, 80 livestock, and 3 tigers have been killed in a year. Now, through WildTeam's work, there is a boat-based Tiger Response team that provides first aid, transport, and body retrieval support for people being killed in the forest by tigers. WildTeam has also set up 49 volunteer Village Response Teams that are trained to save tigers that have strayed into the village areas and would be otherwise killed. These village teams are made up of over 350 volunteers, who are also now supporting anti-poaching work and conservation education/awareness activities. WildTeam also works to empower local communities to access the government funds for compensating the loss/injury of livestock and people from the conflict. To monitor the conflict and assess the effectiveness of actions, WildTeam have also set up a human-tiger conflict data collection and reporting system.

In Nepal

The government aims at doubling the country's tiger population by 2022. In May 2010, Banke National Park was established with an area of 550 km2 (210 sq mi).[109]

"Re-wilding" project in South Africa

In 2000, the Bengal tiger re-wilding project Tiger Canyons was started by John Varty, who together with the zoologist Dave Salmoni trained captive-bred tiger cubs how to stalk, hunt, associate hunting with food and regain their predatory instincts. They claimed that once the tigers proved that they can sustain themselves in the wild, they would be released into a free-range sanctuary of South Africa to fend for themselves.[110]

The project has received controversy after accusations by their investors and conservationists of manipulating the behaviour of the tigers for the purpose of a film production, Living with Tigers, with the tigers believed to be unable to hunt.[111][112] Stuart Bray, who had originally invested a large sum of money in the project, claimed that he and his wife, Li Quan, watched the film crew "[chase] the prey up against the fence and into the path of the tigers just for the sake of dramatic footage."[111][112]

The four tigers involved in this project have been confirmed to be crossbred Siberian–Bengal tigers, which should neither be used for breeding nor being released into the Karoo. Tigers that are not genetically pure will not be able to participate in the tiger Species Survival Plan, as they are not used for breeding, and are not allowed to be released into the wild.[113]

In culture

The tiger is one of the animals displayed on the Pashupati seal of the Indus Valley Civilisation. The tiger crest is the emblem on the Chola coins. The seals of several Chola copper coins show the tiger, the Pandya emblem fish and the Chera emblem bow, indicating that the Cholas had achieved political supremacy over the latter two dynasties. Gold coins found in Kavilayadavalli in the Nellore district of Andhra Pradesh have motifs of the tiger, bow and some indistinct marks.[116]

Today, the tiger is the national animal of India. Bangladeshi banknotes feature a tiger. The political party Muslim League of Pakistan uses the tiger as its election symbol.[117] Tipu Sultan, who ruled Mysore in late 18th-century India, was also a great admirer of the animal. The famed 18th-century automaton, Tipu's Tiger was also created for him.[118] The tiger was the dynastic symbol of this dynasty.[119] The iconography persisted and during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, Punch ran a political cartoon showing the Indian rebels as a tiger, attacking a victim, being defeated by the British forces shown by the larger figure of a lion.[120]

Several people were nicknamed Tiger or Bengal Tiger. Bengali revolutionary Jatindranath Mukherjee was called Bagha Jatin (Bengali for Tiger Jatin). Educator Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee was often called the "Tiger of Bengal".

The Bengal tiger has been used as a logo and a nickname for famous personalities. Some of them are mentioned below:

- Members of the East Bengal Regiment of the Bangladesh Army are nicked 'Bengal Tigers'; the regiment's logo is a tiger face. Senior Tigers is the nickname of the first battalion.

- Canna 'Bengal Tiger' is an Italian canna cultivar with variegated foliage.

In arts

- The main antagonist of The Jungle Book, Shere Khan, is a Bengal tiger.[121]

- The Man-Eaters of Kumaon is based on man-eating tigers and leopards in Kumaon Division.[122]

- The film Tiger of Bengal was produced in 1959.

- In the fantasy adventure novel Life of Pi and in its 2012 film adaptation, a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker is the lead character.[123]

- The Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo is based on a real story of a tiger that escaped from Baghdad Zoo in 2003 and haunts the streets of Baghdad seeking the meaning of life.[124][125][126]

- The 2007 film Maneater is based on Jack Warner's novel Shikar.

- The Lost Land of the Tiger is a documentary by the BBC on tigers in Bhutan.[127]

- Bagh Bahadur (Bengali: বাঘ বাহাদুর, translation: The Tiger Dancer) is a 1989 Bengali drama film, directed and written by Buddhadeb Dasgupta, about a man who paints himself as a tiger and dances in a village in Bengal.

- The 2014 Indian film Roar – Tigers of the Sundarbans is about a white Bengal tigress in the Sundarbans.[128]

In sports

- The Bangladesh Cricket Board's logo features a tiger.[129]

- The flag of the Azad Hind Fauj and the Indian Legion both carried the Springing Tiger on the Flag of India. The Azad Hind Fauj also released postage stamps where the Tricolour's charkha was replaced by the Springing Tiger.[130][131]

- RIT's athletics nickname is the "Tigers". In 1963, RIT purchased a rescued Bengal tiger which became the institute's mascot, named Spirit.[132] RIT's present mascot RITchie is also a Bengal tiger.[133][134]

- Trinity Tigers is the nickname for the sports teams of Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas. The school mascot is LeeRoy, a Bengal tiger. In the 1950s, LeeRoy was an actual tiger who was brought to sporting events,[135]

- University of Memphis's sports teams are known as Memphis Tigers. TOM is the name of three Bengal tigers which have served as the mascot of the sports team since 1972.

- University of Missouri has Truman the Tiger, a Bengal tiger as its mascot; students are known as tigers, their athletic team as Missouri Tigers, and their web space and email as Bengal-space and Bengal-mail.

- Cincinnati's National Football League team is named the Cincinnati Bengals.

Notable individuals

Notable Bengal tigers include the man-eating Tigers of Chowgarh, Chuka man-eating tiger, the Bachelor of Powalgarh and Thak man-eater,[136] Tiger of Segur, Tiger of Mundachipallam, and the Wily Tiger of Mundachipallam.[137]

Tiger versus lion

Apart from the above-mentioned uses of the Bengal tiger in culture, the fight between a tiger and a lion has, for a long time, been a popular topic of discussion by hunters, naturalists, artists, and poets, and continue to inspire the popular imagination to the present-day.[138][139] There have been historical cases of fights between Bengal tigers and lions in captivity.[12][140][141]

See also

- Tiger populations: Bengal tiger · Siberian tiger · Caspian tiger · Indochinese tiger · South China tiger · Malayan tiger · Sumatran tiger · Javan tiger · Bali tiger

- Prehistoric tigers: Panthera tigris soloensis · Panthera tigris trinilensis · Panthera tigris acutidens

References

- Chundawat, R. S.; Khan, J. A. & Mallon, D. P. (2011). "Panthera tigris ssp. tigris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T136899A4348945.

- Mazák, V. (1981). "Panthera tigris" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 152 (152): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504004. JSTOR 3504004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2011.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O'Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 66–68.

- Jhala, Y. V.; Qureshi, Q.; Sinha, P. R. (2011). Status of tigers, co-predators and prey in India, 2010. TR 2011/003 pp-302 (PDF) (Report). New Delhi, Dehradun: National Tiger Conservation Authority, Govt. of India, and Wildlife Institute of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2012.

- Jhala, Y. V.; Qureshi, Q.; Nayak, A. K. (2019). Status of tigers, co-predators and prey in India 2018. Summary Report. TR No./2019/05 (PDF) (Report). New Delhi, Dehradun: National Tiger Conservation Authority & Wildlife Institute of India.

- Poudyal, L.; Yadav, B.; Ranabhat, R.; Maharjan, S.; Malla, S.; Lamichhane, B.R.; Subba, S.; Koirala, S.; Shrestha, S.; Gurung, A.; Paudel, U.; Bhatt, T. & Giri, S. (2018). Status of Tigers and Prey in Nepal (Report). Kathmandu, Nepal: Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation & Department of Forests and Soil Conservation, Ministry of Forests and Environment.

- Sangay, T. & Wangchuk, T. (2005). Tiger Action Plan for Bhutan 2006–2015. Thimphu: Nature Conservation Division, Department of Forests, Ministry of Agriculture, Royal Government of Bhutan and WWF Bhutan Programme.

- Kitchener, A. C. & Dugmore, A. J. (2000). "Biogeographical change in the tiger, Panthera tigris". Animal Conservation Forum. 3 (2): 113–124. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2000.tb00236.x.

- Luo, S. J.; Kim, J.; Johnson, W. E.; van der Walt, J.; Martenson, J.; Yuhki, N.; Miquelle, D. G.; Uphyrkina, O.; Goodrich, J. M.; Quigley, H. B.; Tilson, R.; Brady, G.; Martelli, P.; Subramaniam, V.; McDougal, C.; Hean, S.; Huang, S.; Pan, W.; Karanth, U.; Sunquist, M.; Smith, J. L. D. & O'Brien, S. J. (2004). "Phylogeography and Genetic Ancestry of Tigers (Panthera tigris)". PLOS Biology. 2 (12): e442. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020442. PMC 534810. PMID 15583716.

- Cooper, D. M.; Dugmore, A. J.; Gittings, B. M.; Scharf, A. K.; Wilting, A. & Kitchener, A. C. (2016). "Predicted Pleistocene–Holocene rangeshifts of the tiger (Panthera tigris)". Diversity and Distributions. 22 (11): 1–13. doi:10.1111/ddi.12484.

- Heptner, V. G. & Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Tiger". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 95–202.

- Sankhala, K. (1978). Tiger: The Story of the Indian Tiger. Glasgow: Collins. ISBN 978-0002161244.

- Lytton, E. (1841). The Critical and Miscellaneous Writings of Sir Edward Lytton. Vol. 2. p. 167.

- Pandit, P. K. (2012). "Sundarban Tiger − a new prey species of estuarine crocodile at Sundarban Tiger Reserve, India" (PDF). Tigerpaper. XXXIX (1): 1–5.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis tigris". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 41.

- Pocock, R. I. (1929). "Tigers". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 33 (3): 505–541.

- Kitchener, A. (1999). "Tiger distribution, phenotypic variation and conservation issues". In Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S.; Jackson, P. (eds.). Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in Human-Dominated Landscapes. Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–39. ISBN 978-0-521-64835-6. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012.

- Wilting, A.; Courtiol, A.; Christiansen, P.; Niedballa, J.; Scharf, A. K.; et al. (2015). "Planning tiger recovery: Understanding intraspecific variation for effective conservation". Science Advances. 11 (5: e1400175): e1400175. Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0175W. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400175. PMC 4640610. PMID 26601191.

- Liu, Y.-C.; Sun, X.; Driscoll, C.; Miquelle, D. G.; Xu, X.; et al. (2018). "Genome-wide evolutionary analysis of natural history and adaptation in the world's tigers". Current Biology. 28 (23): 3840–3849. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.09.019. PMID 30482605.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Dugmore, A. J. (2000). "Biogeographical change in the tiger, Panthera tigris". Animal Conservation. 3 (2): 113–124. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2000.tb00236.x.

- McDougal, C. (1977). The Face of the Tiger. London: Rivington Books and André Deutsch.

- Karanth, K. U. (2003). "Tiger ecology and conservation in the Indian subcontinent". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 100 (2–3): 169–189. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012.

- Barlow, A.; Mazák, J.; Ahmad, I. U.; Smith, J. L. D. (2010). "A preliminary investigation of Sundarbans tiger morphology". Mammalia. 74 (3): 329–331. doi:10.1515/mamm.2010.040. S2CID 84134909.

- Sunquist, M.; Sunquist, F. (2002). "Tiger Panthera tigris (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild Cats of the World. University of Chicago Press. pp. 343–372. ISBN 978-0-22-677999-7.

- Smith, J. L. D.; Sunquist, M. E.; Tamang, K. M.; Rai, P. B. (1983). "A technique for capturing and immobilizing tigers". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 47 (1): 255–259. doi:10.2307/3808080. JSTOR 3808080.

- Slaght, J. C.; Miquelle, D. G.; Nikolaev, I. G.; Goodrich, J. M.; Smirnov, E. N.; et al. (2005). "Chapter 6. Who's king of the beasts? Historical and contemporary data on the body weight of wild and captive Amur tigers in comparison with other subspecies" (PDF). In D. G. Miquelle; E. N. Smirnov; J.M. Goodrich (eds.). Tigers in Sikhote-Alin Zapovednik: Ecology and Conservation (in Russian). Vladivostok, Russia: PSP. pp. 25–35.

- Hewett, J. P.; Hewett Atkinson, L. (1938). "Visits to India after Retirement". Jungle trails in northern India: reminiscences of hunting in India. London: Metheun and Company Limited. pp. 177–183.

- Barlow, A. C. D. (2009). "The Sundarbans Tiger – Adaptation, population status, and Conflict management" (PhD thesis). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- Sterndale, R. A. (1884). "Felis Tigris No. 201". Natural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co.

- Brander, A. A. D. (1923). Wild Animals in Central India. London: Edwin Arnold & Co.

- Dinerstein, E. (2003). Return of the Unicorns: Natural History and Conservation of the Greater-One Horned Rhinoceros. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-08450-5.

- Wood, G. L. (1982). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Enfield, Middlesex: Guinness Superlatives. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- Manamendra-Arachchi, K.; Pethiyagoda, R.; Dissanayake, R.; Meegaskumbura, M. (2005). "A second extinct big cat from the late Quaternary of Sri Lanka" (PDF). The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 2005 (Supplement No. 12): 423–434.

- Luo, S.J.; Johnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Applying molecular genetic tools to tiger conservation". Integrative Zoology. 5 (4): 351–362. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00222.x. PMC 6984346. PMID 21392353.

- Wikramanayake, E.D.; Dinerstein, E.; Robinson, J.G.; Karanth, K.U.; Rabinowitz, A.; et al. (1999). "Where can tigers live in the future? A framework for identifying high-priority areas for the conservation of tigers in the wild". In Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S.; Jackson, P. (eds.). Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in Human-Dominated Landscapes. Cambridge University Press. pp. 255–272. ISBN 978-0-521-64835-6. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012.

- Karanth, K. U.; Nichols, J. D.; Seidensticker, J.; Dinerstein, E.; Smith, J. L. D.; et al. (2003). "Science deficiency in conservation practice: the monitoring of tiger populations in India" (PDF). Animal Conservation. 6 (2): 141–146. doi:10.1017/S1367943003003184.

- Jhala, Y. V.; Gopal, R.; Qureshi, Q., eds. (2008). Status of the Tigers, Co-predators, and Prey in India (PDF). TR 08/001. National Tiger Conservation Authority, Govt. of India, New Delhi; Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2013.

- Sadhu, A.; Jayam, P. P. C.; Qureshi, Q.; Shekhawat, R. S.; Sharma, S. & Jhala, Y. V. (2017). "Demography of a small, isolated tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) population in a semi-arid region of western India". BMC Zoology. 2: 16. doi:10.1186/s40850-017-0025-y.

- Jhala, Y. V.; Qureshi, Q.; Gopal, R., eds. (2015). The status of tigers, copredators & prey in India 2014. TR2015/021. New Delhi, Dehradun: National Tiger Conservation Authority & Wildlife Institute of India.

- Kulkarni, D. (2018). "Sahyadri Tiger Reserve camera traps evidence of tigers first time in 8 years". DNA India. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- Ghai, R. (2019). "Camera trap proves Gujarat now has tiger". Down To Earth. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- Kaushik, H. (2019). "Tiger that trekked from MP to Gujarat died of starvation: Post-mortem report". The Times of India. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- Kamat, P. (2019). "Tiger spotted at Goa's only national park". The Hindu. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- Sayed, N. (2019). "Goa's new visitor: Big cat at Molem national park". The Times of India. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- Khan, M. M. H. (2004). Ecology and conservation of the Bengal tiger in the Sundarbans Mangrove forest of Bangladesh (PDF) (PhD thesis). Cambridge: The University of Cambridge.

- Sanderson, E.; Forrest, F.; Loucks, C.; Ginsberg, J.; Dinerstein, E.; et al. (2010). "Setting priorities for the conservation and recovery of wild tigers: 2005–2015" (PDF). In Tilson, R.; Nyhus, P. J. (eds.). Tigers of the World: The Science, Politics and Conservation of Panthera tigris. New York, Washington, D.C. pp. 143–161.

- Global Tiger Initiative (2011). Global Tiger Recovery Program 2010–2022 (PDF). Washington: Global Tiger Initiative Secretariat. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2011.

- Khan, M. (2012). "Population and prey of the Bengal Tiger Panthera tigris tigris (Linnaeus, 1758) (Carnivora: Felidae) in the Sundarbans, Bangladesh". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 4 (2): 2370–2380. doi:10.11609/jott.o2666.2370-80.

- Barlow, A.; Smith, J. L. D.; Ahmad, I. U.; Hossain, A. N.; Rahman, M. & Howlader, A. (2011). "Female tiger Panthera tigris home range size in the Bangladesh Sundarbans: the value of this mangrove ecosystem for the species' conservation". Oryx. 45: 125–128. doi:10.1017/S0030605310001456.

- Barlow, A.; Ahmed, M. I. U.; Rahman, M. M.; Howlader, A.; Smith, A. C. & Smith, J. L. D. (2008). "Linking monitoring and intervention for improved management of tigers in the Sundarbans of Bangladesh". Biological Conservation. 14 (8): 2032–2040. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.05.018.

- Aziz, M. A.; Tollington, S.; Barlow, A.; Greenwood, C.; Goodrich, J. M.; Smith, O.; Shamsuddoha, M.; Islam, M. A. & Groombridge, J. J. (2017). "Using non-invasively collected genetic data to estimate density and population size of tigers in the Bangladesh Sundarbans". Global Ecology and Conservation. 12: 272–282. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2017.09.002.

- Mukul, S. A.; Alamgir, M.; Sohel, M. S. I.; Pert, P. L.; Herbohn, J.; Turton, S. M.; Khan, M. S. I.; Munim, S. A.; Reza, A. A. & Laurance, W. F. (2019). "Combined effects of climate change and sea-level rise project dramatic habitat loss of the globally endangered Bengal tiger in the Bangladesh Sundarbans". Science of the Total Environment. 663: 830–840. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.663..830M. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.383. PMID 30738263.

- Smith, J. L. D.; Ahern, S. C. & McDougal, C. (1998). "Landscape Analysis of Tiger Distribution and Habitat Quality in Nepal". Conservation Biology. 12 (6): 1338–1346. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1998.97068.x.

- Dhakal, M.; Karki (Thapa), M.; Jnawali, S. R.; Subedi, N.; Pradhan, N. M. B.; Malla, S.; Lamichhane, B. R.; Pokheral, C. P.; Thapa, G. J.; Oglethorpe, J.; Subba, S. A.; Bajracharya, P. R. & Yadav, H. (2014). Status of Tigers and Prey in Nepal. Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (Report). Kathmandu, Nepal.

- Dorji, D. P. & Santiapillai, C. (1989). "The Status, Distribution and Conservation of the Tiger Panthera tigris in Bhutan" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 48 (4): 311–319. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(89)90105-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2012.

- Wang, S.W. & Macdonald, D.W. (2009). "The use of camera traps for estimating tiger and leopard populations in the high altitude mountains of Bhutan". Biological Conservation. 142 (3): 606–613. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.11.023.

- Dorji, S.; Thinley, P.; Tempa, T.; Wangchuk, N.; Tandin; Namgyel, U. & Tshewang, S. (2015). Counting the Tigers in Bhutan: Report on the National Tiger Survey of Bhutan 2014 - 2015 (Report). Thimphu, Bhutan: Department of Forests and Park Services, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests.

- Jigme, K. & Tharchen, L. (2012). "Camera-trap records of tigers at high altitudes in Bhutan". Cat News (56): 14–15.

- Thinley, P.; Dendup, T.; Rajaratnam, R.; Vernes, K.; Tempa, K.; Chophel, T. & Norbu, L. (2020). "Tiger reappearance in Bhutan's Bumdeling Wildlife Sanctuary: a case for maintaining effective corridors and metapopulations". Animal Conservation. 23 (6): 629–631. doi:10.1111/acv.12580.

- Smith, J. L. D. (1993). "The role of dispersal in structuring the Chitwan tiger population". Behaviour. 124 (3): 165–195. doi:10.1163/156853993X00560.

- Chundawat, T. S.; Gogate, N.; Johnsingh, A. J. T. (1999). "Tigers in Panna: preliminary results from an Indian tropical dry forest". In Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S.; Jackson, P. (eds.). Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in Human-Dominated Landscapes. Cambridge University Press. pp. 123–129. ISBN 978-0-521-64835-6.

- Barlow, A. C. D.; McDougal, C.; Smith, J. L. D.; Gurung, B.; Bhatta, S. R.; et al. (2009). "Temporal Variation in Tiger (Panthera tigris) Populations and Its Implications for Monitoring". Journal of Mammalogy. 90 (2): 472–478. doi:10.1644/07-MAMM-A-415.1.

- Bagchi, S.; Goyal, S. P. & Sankar, K. (2003). "Prey abundance and prey selection by tigers (Panthera tigris) in a semi-arid, dry deciduous forest in western India" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 260 (3): 285–290. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.7051. doi:10.1017/S0952836903003765.

- Andheria, A. P.; Karanth, K. U. & Kumar, N. S. (2007). "Diet and prey profiles of three sympatric large carnivores in Bandipur Tiger Reserve, India" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 273 (2): 169–175. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00310.x.

- Biswas, S. & Sankar, K. (2002). "Prey abundance and food habit of tigers (Panthera tigris tigris) in Pench National Park, Madhya Pradesh, India". Journal of Zoology. 256 (3): 411–420. doi:10.1017/S0952836902000456.

- Wegge, P.; Odden, M.; Pokharel, C. Pd. & Storaasc, T. (2009). "Predator–prey relationships and responses of ungulates and their predators to the establishment of protected areas: A case study of tigers, leopards and their prey in Bardia National Park, Nepal". Biological Conservation. 142: 189–202. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.10.020.

- Prachi, M. & Kulkarni, J. (2006). Monitoring of Tiger and Prey Population Dynamics in Melghat Tiger Reserve, Maharashtra, India (Report). Pune: Envirosearch.

- Dutta, P. (2008). "Trouble for rhino from poacher and Bengal tiger". The Telegraph India. Archived from the original on 27 September 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- Huckelbridge, D. (2019). No Beast So Fierce. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9780062678843.

- Karanth, K. U. & Sunquist, M. E. (1995). "Prey selection by tiger, leopard and dhole in tropical forests". Journal of Animal Ecology. 64 (4): 439–450. doi:10.2307/5647. JSTOR 5647.

- Mazak, V. (1996). Der Tiger : Panthera tigris. Magdeburg, Heidelberg, Berlin, Oxford: Westarp Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-89432-759-0.

- Sanderson, G. P. (1912). Thirteen years among the wild beasts of India: their haunts and habits from personal observations; with an account of the modes of capturing and taming elephants. Edinburgh: John Grant.

- Schaller, G. (1967). The Deer and the Tiger: A Study of Wildlife in India. Chicago: Chicago University Press. ISBN 9780226736570.

- Buncombe, A. (31 October 2007). "The face of a doomed species". The Independent.

- Banks, D.; Lawson, S. & Wright, B. (2006). Skinning the Cat: Crime and Politics of the Big Cat Skin Trade (PDF) (Report). London: Environmental Investigation Agency, Wildlife Protection Society of India.

- Saif, S.; Rahman, H. M. T. & MacMillan, D. C. (2016). "Who is killing the tiger Panthera tigris and why?". Oryx. 52: 1–9. doi:10.1017/S0030605316000491.

- Saif, S.; Russell, A. M.; Nodie, S. I.; Inskip, C.; Lahann, P.; Barlow, A.; Barlow Greenwood, C.; Islam, M. A. & MacMillan, D. C. (2016). "Local Usage of Tiger Parts and Its Role in Tiger Killing in the Bangladesh Sundarbans". Human Dimensions of Wildlife. 21 (2): 95–110. doi:10.1080/10871209.2015.1107786. S2CID 147189479.

- Hemley, G. & Mills, J. A. (1999). "The beginning of the end of tigers in trade?". In Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S. & Jackson, P. (eds.). Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in Human-Dominated Landscapes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64835-6.

- "WPSI's Tiger Poaching Statistics". Wildlife Protection Society of India. 2009.

- Sankar, K.; Qureshi, Q.; Nigam, P.; Malik, P. K.; Sinha, P. R.; Mehrotra, R. N.; Gopal, R.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Mondal, K. & Shilpi Gupta (2010). "Monitoring of reintroduced tigers in Sariska Tiger Reserve, Western India: preliminary findings on home range, prey selection and food habits". Tropical Conservation Science. 3 (3): 301–318. doi:10.1177/194008291000300305.

- Banerjee, B. (2007). "Tiger Poaching Ring Busted by Indian Police". National Geographic Society News. Associated Press.

- Ali, F. M. (2009). "Indian tiger park has no tigers". BBC News.

- Wildlife Watch Group (2011). "Central India Loses Four Tigers, including the Legendary B2". Wildlife Times (20): 9.

- McDougal, C. (1987). "The man-eating tigers in geographical historical perspective". In Tilson, R. L.; Seal, U. S. (eds.). Tigers of the World: The Biology, Biopolitics, Management, and Conservation of an Endangered Species. New Jersey: Noyes Publications. pp. 435–448. ISBN 978-0-8155-1133-5.

- Hendrichs, H. (1975). "The status of the tiger (Panthera tigris) in the Sundarbans Mangrove". Säugetierkundliche Mitteilungen. 23: 161–199.

- Jackson, P. (1985). "Man-eaters". International Wildlife. 15: 4–11.

- "Straying tiger meets with a bloody end". The Hindu. 3 December 2012.

- Manoj, E. M. (3 December 2012). "Tiger gone, but tension simmers". The Hindu.

- Damania, R., Seidensticker, J., Whitten, T., Sethi, G., Mackinnon, K., Kiss, A., Kushlin, A. (2008). A Future for Wild Tigers. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

- "WWF and leonardo partner to protect Tiger Habitat through Save Tigers Now". SaveTigersNow.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- "Global Tiger Conservation initiative kick started Conservation Campaign in 2010". World Wild Fund. 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Panwar, H. S. (1987). "Project Tiger: The reserves, the tigers, and their future". In: Tilson, R. L., Seal, U. S., Minnesota Zoological Garden, IUCN/SSC Captive Breeding Group, IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. Tigers of the world: the biology, biopolitics, management, and conservation of an endangered species. Noyes Publications, Park Ridge, N.J., pp. 110–117, ISBN 0815511337.

- Background. National Tiger Conservation Authority, Government of India

- Ramesh, R. (2008). "Indian wild tiger numbers almost halve". Guardian News and Media Limited.

- Sethi, N. (2008). "Just 1,411 tigers in India". The Times of India. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- Sharma, A. (2008). article "India Reports Sharp Decline in Wild Tigers". National Geographic News, 13 February 2008.

- Page, J. (2008). "Tigers flown by helicopter to Sariska reserve to lift numbers in western India". The Times. London. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- "The great Panna cover-up". NDTV. 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- "India launches anti-poaching force to curb tiger, wildlife trade". The Earth Times. 2008. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013.

- Sebastian, S. (2009). "Tigers galore in Ranthambhore National Park". The Hindu.

- Sharma, R. (2017). "Tired of Gujarat reluctance on Gir lions, MP to release tigers in Kuno". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- "Stalemate on translocation of Gir lions Kuno Palpur in Madhya Pradesh to be used as tiger habitat now". Hindustan Times. 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Luo, S.; Johnson, W. E.; Martenson, J.; Antunes, A.; Martelli, P.; et al. (2008). "Subspecies Genetic Assignments of Worldwide Captive Tigers Increase Conservation Value of Captive Populations". Current Biology. 18 (8): 592–596. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.053. PMID 18424146.

- Singh, A. (1981). Tara, a tigress. London and New York: Quartet Books. ISBN 070432282X.

- Shankaranarayanan, P. & Singh, L. (1998). "Mitochondrial DNA sequence divergence among big cats and their hybrids". Current Science. 75 (9): 919–923.

- Shankaranarayanan, P.; Banerjee, M.; Kacker, R. K.; Aggarwal, R. K. & Singh, L. (1997). "Genetic variation in Asiatic lions and Indian tigers" (PDF). Electrophoresis. 18 (9): 1693–1700. doi:10.1002/elps.1150180938. PMID 9378147. S2CID 41046139.

- Menon, S. (1997). "Tainted Royalty". India Today. Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- Srivastav, A.; Malviya, M.; Tyagi, P.C. & Nigam, P. (2011). Indian National Studbook of Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) (PDF) (Report). New Delhi, Dehradun: Central Zoo Authority, Wildlife Institute of India.

- Bhushal, R. P. (2010). "Nod to Banke National Park". The Himalayan Times.

- "Meet the Tiger Men: John Varty". Discovery Channel. 2001. Archived from the original on 3 June 2008.

- "Tiger Film a Fraud, says The Chinese Tigers South African Trust". PR Newswire. 2003. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011.

- "Discovery Film Proclaimed A Fraud; Broadcaster to be Sued". Wildlife Film News 56. February 2004. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- Arrick, A.; Mckinney, K. (2007). "Purrrfect Breed?". TylerPaper. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009.

- Nilakanta Sastri, K. A. (2003). A history of South India : from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar (Fourth ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195606868.

- Chopra, P. N.; Ravindran, T. K. & Subrahmanian, N. (2003). History of South India; Ancient, Medieval and Modern. New Delhi: S. Chand & Company Ltd. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-219-0153-6.

- Singh, U. (2008). "Numismatics: the study of coins". A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. India: Pearson Education. pp. 51–57. ISBN 978-8131711200.

- Jackson, P. (1999). "The tiger in human consciousness and its significance in crafting solutions for tiger conservation". In Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S.; Jackson, P. (eds.). Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in Human-Dominated Landscapes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–54. ISBN 978-0-521-64835-6.

- Brittlebank, K. (May 1995). "Sakti and Barakat: The Power of Tipu's Tiger. An Examination of the Tiger Emblem of Tipu Sultan of Mysore". Modern Asian Studies. 29 (2): 257–269. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00012725. JSTOR 312813.

- Sramek, J. (2006). "'Face Him Like a Briton': Tiger Hunting, Imperialism, and British Masculinity in Colonial India, 1800–1875". Victorian Studies. 48 (4): 659–680. doi:10.2979/vic.2006.48.4.659. JSTOR 4618910. S2CID 145632352.

- Carter, T. (1893). War medals of the British army, and how they were won (Revised, enlarged ed.). London: W. H. Long. OL 14047956M.

- Kipling, R. (1910). The Jungle Book. London: Macmillan.

- Corbett, J. (1944). Man-Eaters of Kumaon. Bombay: Oxford University Press.

- Martel, Y. (2001). Life of Pi (First ed.). Toronto: Knopf Canada. ISBN 0-676-97376-0.

- "Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo". centertheatregroup.org. Center Theatre Group. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- Rod Nordland (7 August 2008). "Tigers Return to Baghdad". Newsweek. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Itzkoff, D. (2008). "N.E.A. Gives Grants to Seven Productions". The New York Times.

- "BBC team discovers "lost" tigers". BBC Press Office. 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- Sadanah, K. /director) (2014). Roar: Tigers of the Sundarbans (Motion picture). Mumbai: Abiz Rizvi Film.

- "Bangladesh Cricket Board". ICC. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "Raising a flag". The Telegraph. 2010.

- Toye, H. (2009). The Springing Tiger. Allied Publishers.

- "RIT – 175 Year Anniversary". .rit.edu. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- "RIT – Prospectus" (PDF). Rochester Institute of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- "RIT – RIT Archives – Spirit of RIT". Rochester Institute of Technology. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- "Lee Roy the Tiger". Trinity Digital Collection. Trinity University. Retrieved 30 October 2007.

- Corbett, J. (1944). Man-Eaters of Kumaon. London: Oxford University Press.

- Anderson, K. (1955). Nine Man-Eaters and One Rogue. New York: Dutton.

- Gasset, J. O. (2007). "The Essence of Hunting". Meditations on Hunting (Second ed.). Belgrade: Wilderness Adventure Press, Inc. pp. 55–66. ISBN 978-1-932098-53-2.

- Thomas, I. (2006). Lion vs. Tiger. Raintree. ISBN 978-1-4109-2398-1.

- Porter, J. H. (1894). Wild beasts; a study of the characters and habits of the elephant, lion, leopard, panther, jaguar, tiger, puma, wolf, and grizzly bear. New York: C. Scribner's sons. p. 239.

- Beatty, C. (1939). "Which is the King of Beasts". Popular Mechanics. p. 563. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

Further reading

- Schnitzler, A.; Hermann, L. (2019). "Chronological distribution of the tiger Panthera tigris and the Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica in their common range in Asia". Mammal Review. 49 (4): 340–353. doi:10.1111/mam.12166.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panthera tigris tigris. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Panthera tigris tigris. |

- "Panthera t. tigris". Cat Specialist Group.

- "Tiger conservation in the Bangladesh Sundarbans". WildTeam.

- "Bengal Tiger". Panthera.

- Li, Y. & H. Liqiang (2019). "Bengal tigers found in Tibet, with plenty of prey". China Daily.

- "The four faces of the Bengal tiger". Guardian News and Media Limited.

- "Himalayan black bear killed by tiger". Big Cat Rescue.