Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (/mʊˈɡɑːbi/;[1] Shona: [muɡaɓe]; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) from 1975 to 1980 and led its successor political party, the ZANU – Patriotic Front (ZANU–PF), from 1980 to 2017. Ideologically an African nationalist, during the 1970s and 1980s he identified as a Marxist–Leninist, and as a socialist after the 1990s.

Mugabe was born to a poor Shona family in Kutama, Southern Rhodesia. Educated at Kutama College and the University of Fort Hare, he worked as a schoolteacher in Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia, and Ghana. Angered by white minority rule of his homeland within the British Empire, Mugabe embraced Marxism and joined African nationalists calling for an independent state controlled by the black majority. After making anti-government comments, he was convicted of sedition and imprisoned between 1964 and 1974. On release, he fled to Mozambique, established his leadership of ZANU, and oversaw its role in the Rhodesian Bush War, fighting Ian Smith's predominately white government. He reluctantly participated in peace talks in the United Kingdom that resulted in the Lancaster House Agreement, putting an end to the war. In the 1980 general election, Mugabe led ZANU-PF to victory, becoming Prime Minister when the country, now renamed Zimbabwe, gained internationally recognised independence later that year. Mugabe's administration expanded healthcare and education and—despite his professed desire for a socialist society—adhered largely to mainstream, conservative economic policies.

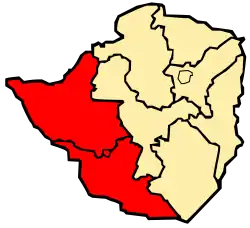

Mugabe's calls for racial reconciliation failed to stem growing white emigration, while relations with Joshua Nkomo's Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) also deteriorated. In the Gukurahundi of 1982–1987, Mugabe's Fifth Brigade crushed ZAPU-linked opposition in Matabeleland in a campaign that killed at least 10,000 people, mostly Ndebele civilians. Internationally he sent troops into the Second Congo War and chaired the Non-Aligned Movement (1986–89), the Organisation of African Unity (1997–98), and the African Union (2015–16). Pursuing decolonisation, Mugabe emphasised the redistribution of land controlled by white farmers to landless blacks, initially on a "willing seller–willing buyer" basis. Frustrated at the slow rate of redistribution, from 2000 he encouraged black Zimbabweans to violently seize white-owned farms. Food production was severely impacted, leading to famine, economic decline, and Western sanctions. Opposition to Mugabe grew, but he was re-elected in 2002, 2008, and 2013 through campaigns dominated by violence, electoral fraud, and nationalistic appeals to his rural Shona voter base. In 2017, members of his party ousted him in a coup, replacing him with former vice president Emmerson Mnangagwa.

Having dominated Zimbabwe's politics for nearly four decades, Mugabe was a controversial figure. He was praised as a revolutionary hero of the African liberation struggle who helped free Zimbabwe from British colonialism, imperialism, and white minority rule. Critics accused Mugabe of being a dictator responsible for economic mismanagement, widespread corruption in Zimbabwe, anti-white racism, human rights abuses, and crimes against humanity.

Early life

Childhood: 1924–1945

Robert Gabriel Mugabe was born on 21 February 1924 at the Kutama Mission village in Southern Rhodesia's Zvimba District.[2] His father, Gabriel Matibiri, was a carpenter while his mother Bona was a Christian catechist for the village children.[3] They had been trained in their professions by the Jesuits, the Roman Catholic religious order which had established the mission.[4] Bona and Gabriel had six children: Miteri (Michael), Raphael, Robert, Dhonandhe (Donald), Sabina, and Bridgette.[5] They belonged to the Zezuru clan, one of the smallest branches of the Shona tribe.[6] Mugabe's paternal grandfather was Chief Constantine Karigamombe, alias "Matibiri", a powerful figure who served King Lobengula in the 19th century.[7] Through his father, he claimed membership of the chieftaincy family that has provided the hereditary rulers of Zvimba for generations.[8]

The Jesuits were strict disciplinarians and under their influence Mugabe developed an intense self-discipline,[4] while also becoming a devout Catholic.[9] Mugabe excelled at school,[10] where he was a secretive and solitary child,[11] preferring to read, rather than playing sports or socialising with other children.[12] He was taunted by many of the other children, who regarded him as a coward and a mother's boy.[13]

In about 1930 Gabriel had an argument with one of the Jesuits, and as a result the Mugabe family was expelled from the mission village by its French leader, Father Jean-Baptiste Loubière.[14] The family settled in a village about 11 kilometres (7 miles) away; the children were permitted to remain at the mission primary school, living with relatives in Kutama during term-time and returning to their parental home on weekends.[10] Around the same time, Robert's older brother Raphael died, likely of diarrhoea.[10] In early 1934, Robert's other older brother, Michael, also died, after consuming poisoned maize.[15] Later that year, Gabriel left his family in search of employment in Bulawayo.[16] He subsequently abandoned Bona and their six children and established a relationship with another woman, with whom he had three further offspring.[17]

Loubière died shortly after and was replaced by an Irishman, Father Jerome O'Hea, who welcomed the return of the Mugabe family to Kutama.[10] In contrast to the racism that permeated Southern Rhodesian society, under O'Hea's leadership the Kutama Mission preached an ethos of racial equality.[18] O'Hea nurtured the young Mugabe; shortly before his death in 1970 he described the latter as having "an exceptional mind and an exceptional heart".[19] As well as helping provide Mugabe with a Christian education, O'Hea taught him about the Irish War of Independence, in which Irish revolutionaries had overthrown the British imperial regime.[20] After completing six years of elementary education, in 1941 Mugabe was offered a place on a teacher training course at Kutama College. Mugabe's mother could not afford the tuition fees, which were paid in part by his grandfather and in part by O'Hea.[21] As part of this education, Mugabe began teaching at his old school, earning £2 per month, which he used to support his family.[22] In 1944, Gabriel returned to Kutama with his three new children, but died shortly after, leaving Robert to take financial responsibility for both his three siblings and three half-siblings.[22] Having attained a teaching diploma, Mugabe left Kutama in 1945.[23]

University education and teaching career: 1945–1960

During the following years, Mugabe taught at various schools around Southern Rhodesia,[24] among them the Dadaya Mission school in Shabani.[25] There is no evidence that Mugabe was involved in political activity at the time, and he did not participate in the country's 1948 general strike.[26] In 1949 he won a scholarship to study at the University of Fort Hare in South Africa's Eastern Cape.[27] There he joined the African National Congress youth league (ANCYL)[28] and attended African nationalist meetings, where he met a number of Jewish South African communists who introduced him to Marxist ideas.[29] He later related that despite this exposure to Marxism, his biggest influence at the time were the actions of Mahatma Gandhi during the Indian independence movement.[30] In 1952, he left the university with a Bachelor of Arts degree in history and English literature.[31] In later years he described his time at Fort Hare as the "turning point" in his life.[32]

.jpg.webp)

Mugabe returned to Southern Rhodesia in 1952,[33] by which time—he later related— he was "completely hostile to the [colonialist] system".[34] Here, his first job was as a teacher at the Driefontein Roman Catholic Mission School near Umvuma.[28] In 1953 he relocated to the Highfield Government School in Salisbury's Harari township and in 1954 to the Mambo Township Government School in Gwelo.[35] Meanwhile, he gained a Bachelor of Education degree by correspondence from the University of South Africa,[36] and ordered a number of Marxist tracts—among them Karl Marx's Capital and Friedrich Engels' The Condition of the Working Class in England—from a London mail-order company.[37] Despite his growing interest in politics, he was not active in any political movement.[34] He joined a number of inter-racial groups, such as the Capricorn Africa Society, through which he mixed with both black and white Rhodesians.[38] Guy Clutton-Brock, who knew Mugabe through this group, later noted that he was "an extraordinary young man" who could be "a bit of a cold fish at times" but "could talk about Elvis Presley or Bing Crosby as easily as politics".[39]

From 1955 to 1958, Mugabe lived in neighbouring Northern Rhodesia, where he worked at Chalimbana Teacher Training College in Lusaka.[36] There he continued his education by working on a second degree by correspondence, this time a Bachelor of Administration from the University of London International Programmes through distance and learning. [36] In Northern Rhodesia, he was taken in for a time by the family of Emmerson Mnangagwa, whom Mugabe inspired to join the liberation movement and who would later go on to be President of Zimbabwe.[40] In 1958, Mugabe moved to Ghana to work at St Mary's Teacher Training College in Takoradi.[41] He taught at Apowa Secondary School, also at Takoradi, after obtaining his local certification at Achimota College (1958–1960), where he met his first wife, Sally Hayfron.[42] According to Mugabe, "I went [to Ghana] as an adventurist. I wanted to see what it would be like in an independent African state".[43] Ghana had been the first African state to gain independence from European colonial powers and under the leadership of Kwame Nkrumah underwent a range of African nationalist reforms; Mugabe revelled in this environment.[44] In tandem with his teaching, Mugabe attended the Kwame Nkrumah Ideological Institute in Winneba.[45] Mugabe later claimed that it was in Ghana that he finally embraced Marxism.[46] He also began a relationship there with Hayfron who worked at the college and shared his political interests.[47]

Revolutionary activity

Early political career: 1960–1963

While Mugabe was teaching abroad, an anti-colonialist African nationalist movement was established in Southern Rhodesia. It was first led by Joshua Nkomo's Southern Rhodesia African National Congress, founded in September 1957 and then banned by the colonial government in February 1959.[48] SRANC was replaced by the more radically oriented National Democratic Party (NDP), founded in January 1960.[49] In May 1960, Mugabe returned to Southern Rhodesia, bringing Hayfron with him.[50] The pair had planned for their visit to be short, however Mugabe's friend, the African nationalist Leopold Takawira, urged them to stay.[51]

.jpg.webp)

In July 1960, Takawira and two other NDP officials were arrested; in protest, Mugabe joined a demonstration of 7,000 people who planned to march from Highfield to the Prime Minister's office in Salisbury. The demonstration was stopped by riot police outside Stoddart Hall in Harare township.[52] By midday the next day, the crowd had grown to 40,000 and a makeshift platform had been erected for speakers. Having become a much-respected figure through his profession, his possession of three degrees, and his travels abroad, Mugabe was among those invited to speak to the crowd.[53] Following this event, Mugabe decided to devote himself full-time to activism, resigning his teaching post in Ghana (after having served two years of the four-year teaching contract).[54] He chaired the first NDP congress, held in October 1960, assisted by Chitepo on the procedural aspects. Mugabe was elected the party's publicity secretary.[55] Mugabe consciously injected emotionalism into the NDP's African nationalism, hoping to broaden its support among the wider population by appealing to traditional cultural values.[56] He helped to form the NDP Youth Wing and encouraged the incorporation of ancestral prayers, traditional costume, and female ululation into its meetings.[57] In February 1961 he married Hayfron in a Roman Catholic ceremony conducted in Salisbury; she had converted to Catholicism to make this possible.[58]

The British government held a Salisbury conference in 1961 to determine Southern Rhodesia's future. Nkomo led an NDP delegation, which hoped that the British would support the creation of an independent state governed by the black majority. Representatives of the country's white minority—who then controlled Southern Rhodesia's government—were opposed to this, promoting continued white minority rule.[59] Following negotiations, Nkomo agreed to a proposal which would allow the black population representation through 15 of the 65 seats in the country's parliament. Mugabe and others in the NDP were furious at Nkomo's compromise.[60] Following the conference, Southern Rhodesia's African nationalist movement fell into disarray.[61] Mugabe spoke at a number of NDP rallies before the party was banned by the government in December 1961.[62] Many of its members re-grouped as the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) several days later,[63] with Mugabe appointed as ZAPU's publicity secretary and general secretary.[64]

Racial violence was growing in the country, with aggrieved black Africans targeting the white community.[65] Mugabe deemed such conflict a necessary tactic in the overthrow of British colonial dominance and white minority rule. This contrasted with Nkomo's view that African nationalists should focus on international diplomacy to encourage the British government to grant their demands.[65] Nine months after it had been founded, ZAPU was also banned by the government,[63] and in September 1962 Mugabe and other senior party officials were arrested and restricted to their home districts for three months.[63] Both Mugabe and his wife were in trouble with the law; he had been charged with making subversive statements in a public speech and awarded bail before his trial.[66] Hayfron had been sentenced to two years imprisonment—suspended for 15 months—for a speech in which she declared that the British Queen Elizabeth II "can go to hell".[67]

— Mugabe, early 1960s[68]

The rise of African nationalism generated a white backlash in Southern Rhodesia, with the right-wing Rhodesian Front winning the December 1962 general election. The new government sought to preserve white minority rule by tightening security and establishing full independence from the United Kingdom.[69] Mugabe met with colleagues at his house in Salisbury's Highbury district, where he argued that as political demonstrations were simply being banned, it was time to move towards armed resistance.[70] Both he and others rejected Nkomo's proposal that they establish a government-in-exile in Dar es Salaam.[71] He and Hayfron skipped bail to attend a ZAPU meeting in the Tanganyikan city.[72] There, the party leadership met Tanganyika's President, Julius Nyerere, who also dismissed the idea of a government-in-exile and urged ZAPU to organise their resistance to white minority rule within Southern Rhodesia itself.[73]

In August, Hayfron gave birth to Mugabe's son, whom they named Nhamodzenyika, a Shona term meaning "suffering country".[74] Mugabe insisted that she take their son back to Ghana, while he decided to return to Southern Rhodesia.[75] There, African nationalists opposed to Nkomo's leadership had established a new party, the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), in August; Ndabaningi Sithole became the group's president, while appointing Mugabe to be the group's secretary-general in absentia.[76] Nkomo responded by forming his own group, the People's Caretaker Council, which was widely referred to as "ZAPU" after its predecessor.[77] ZAPU and ZANU violently opposed one another and soon gang warfare broke out between their rival memberships.[78][79]

Imprisonment: 1963–1975

Mugabe was arrested on his return to Southern Rhodesia in December 1963.[80] His trial lasted from January to March 1964, during which he refused to retract the subversive statements that he had publicly made.[81] In March 1964 he was sentenced to 21 months imprisonment.[78] Mugabe was first imprisoned at Salisbury Maximum Security Prison, before being moved to the Wha Wha detention centre and then the Sikombela detention centre in Que Que.[82] At the latter, he organised study classes for the inmates, teaching them basic literacy, maths, and English.[83] Sympathetic black warders smuggled messages from Mugabe and other members of the ZANU executive committee to activists outside the prison.[84] At the executive's bidding, ZANU activist Herbert Chitepo had organised a small guerrilla force in Lusaka. In April 1966 the group carried out a failed attempt to destroy power pylons at Sinoia, and shortly after attacked a white-owned farm near Hartley, killing its inhabitants.[85] The government responded by returning the members of the ZANU executive, including Mugabe, to Salisbury Prison in 1966.[86] There, forty prisoners were divided among four communal cells, with many sleeping on the concrete floor due to overcrowding;[87] Mugabe shared his cell with Sithole, Enos Nkala, and Edgar Tekere.[88] He remained there for eight years, devoting his time to reading and studying.[88] During this period he gained several further degrees from the University of London: a masters in economics, a bachelor of administration, and two law degrees.[89]

While imprisoned, Mugabe learned that his son had died of encephalitis at the age of three. Mugabe was grief-stricken and requested a leave of absence to visit his wife in Ghana. He never forgave the prison authorities for refusing this request.[90] Claims have also circulated among those who knew him at the time that Mugabe was subjected to both physical and mental torture during his imprisonment.[91] According to Father Emmanuel Ribeiro, who was Mugabe's priest during his imprisonment, Mugabe got through the experience "partly through the strength of his spirituality" but also because his "real strength was study and helping others to learn".[92]

While Mugabe was imprisoned, in August 1964, the Rhodesian Front government—now under the leadership of Ian Smith—banned ZANU and ZAPU and arrested all remaining leaders of the country's African nationalist movement.[93] Smith's government made a unilateral declaration of independence from the United Kingdom in November 1965, renaming Southern Rhodesia as Rhodesia; the UK refused to recognise the legitimacy of this and imposed economic sanctions on the country.[94]

In 1972, the African nationalists launched a guerrilla war against Smith's government.[95] Among the revolutionaries, it was known as the "Second Chimurenga".[96] Paramilitary groups based themselves in neighbouring Tanzania and Zambia; many of their fighters were inadequately armed and trained.[97] ZANU's military wing, the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA), consisted largely of Shona. It was based in neighbouring Mozambique and gained funds from the People's Republic of China. ZAPU's military wing, the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA), was instead funded by the Soviet Union, was based in Zambia, and consisted largely of Ndebele.[98]

Mugabe and other senior ZANU members had growing doubts about Sithole's leadership, deeming him increasingly irritable and irrational.[99] In October 1968 Sithole had tried to smuggle a message out of the prison commanding ZANU activists to assassinate Smith. His plan was discovered and he was put on trial in January 1969; desperate to avoid a death sentence, he declared that he renounced violence and his previous ideological commitments.[100] Mugabe denounced Sithole's "treachery" in rejecting ZANU's cause, and the executive removed him as ZANU President in a vote of no confidence, selecting Mugabe as his successor.[101] In November 1974, the ZANU executive voted to suspend Sithole's membership of the organisation.[102]

Fearing that the guerrilla war would spread south, the South African government pressured Rhodesia to advance the process of détente with the politically moderate black governments of Zambia and Tanzania. As part of these negotiations, Smith's government agreed to release a number of black revolutionaries who had been indefinitely detained.[103] After almost eleven years of imprisonment, Mugabe was released in November 1974.[104] He moved in with his sister Sabina at her home in Highfield township.[105] He was intent on joining the ZANU forces and taking part in the guerrilla war,[106] recognising that to secure dominance of ZANU he would have to take command of ZANLA.[107] This was complicated by internal violence within the paramilitary group, predominately between members of the Manyika and Karange groups of Shona.[108]

Guerrilla war: 1975–1979

In March 1975, Mugabe resolved to leave Rhodesia for Mozambique, ambitious to take control of ZANU's guerrilla campaign.[109] After his friend Maurice Nyagumbo was arrested, he feared the same fate but was hidden from the authorities by Ribeiro. Ribeiro and a sympathetic nun then assisted him and Edgar Tekere in smuggling themselves into Mozambique.[110] Mugabe remained in exile there for two years.[111] Mozambique's Marxist President Samora Machel was sceptical of Mugabe's leadership abilities and was unsure whether to recognise him as ZANU's legitimate leader. Machel gave him a house in Quelimane and kept him under partial house arrest, with Mugabe requiring permission to travel.[112] It would be almost a year before Machel accepted Mugabe's leadership of ZANU.[107]

Mugabe travelled to various ZANLA camps in Mozambique to build support among its officers.[113] By mid-1976, he had secured the allegiance of ZANLA's military commanders and established himself as the most prominent guerrilla leader battling Smith's regime.[107] In August 1977, he was officially declared ZANU President at a meeting of the party's central committee held in Chimoio.[114] During the war, Mugabe remained suspicious of many of ZANLA's commanders and had a number of them imprisoned.[115] In 1977 he imprisoned his former second-in-command, Wilfred Mhanda, for suspected disloyalty.[115] After Josiah Tongogara was killed in a car accident in 1979, there were suggestions made that Mugabe may have had some involvement in it; these rumours were never substantiated.[116]

Mugabe remained aloof from the day-to-day military operations of ZANLA, which he entrusted to Tongogara.[107] In January 1976, ZANLA launched its first major infiltration from Mozambique, with nearly 1000 guerrillas crossing the border to attack white-owned farms and stores.[117] In response, Smith's government enlisted all men under the age of 35, expanding the Rhodesian army by 50%.[117] ZANLA's attacks forced large numbers of white landowners to abandon their farms; their now-unemployed black workers joined ZANLA by the thousands.[118] By 1979, ZANLA were in a position to attack a number of Rhodesian cities.[119] Over the course of the war, at least 30,000 people were killed.[120] As a proportion of their wider population, the whites had higher number of fatalities,[120] and by the latter part of the decade the guerrillas were winning.[121]

Mugabe focused on the propaganda war, making regular speeches and radio broadcasts.[107] In these, he presented himself as a Marxist-Leninist, speaking warmly of Marxist-Leninist revolutionaries like Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, and Fidel Castro.[115] Despite his Marxist views, Mugabe's meetings with Soviet representatives were unproductive, for they insisted on Nkomo's leadership of the revolutionary struggle.[122] His relationship with the People's Republic of China was far warmer, as the Chinese Marxist government supplied ZANLA with armaments without any conditions.[123] He also sought support from Western nations, visiting Western embassies in Mozambique,[124] and travelled to both Western states like Italy and Switzerland and Marxist-governed states like the Soviet Union, China, North Korea, Vietnam, and Cuba.[125]

Mugabe called for the overthrow of Rhodesia's predominately white government, the execution of Smith and his "criminal gang", the expropriation of white-owned land, and the transformation of Rhodesia into a one-party Marxist state.[126] He repeatedly called for violence against the country's white minority,[127] referring to white Rhodesians as "blood-sucking exploiters", "sadistic killers", and "hard-core racists".[115] In one typical example, taken from a 1978 radio address, Mugabe declared: "Let us hammer [the white man] to defeat. Let us blow up his citadel. Let us give him no time to rest. Let us chase him in every corner. Let us rid our home of this settler vermin".[127] For Mugabe, armed struggle was an essential part of the establishment of a new state.[128] In contrast to other black nationalist leaders like Nkomo, Mugabe opposed a negotiated settlement with Smith's government.[128] In October 1976 ZANU nevertheless established a joint-platform with ZAPU known as the Patriotic Front.[129] In September 1978 Mugabe met with Nkomo in Lusaka. He was angry with the latter's secret attempts to negotiate with Smith.[130]

Lancaster House Agreement: 1979

The beginning of the end for Smith came when South African Prime Minister B. J. Vorster concluded that white minority rule was unsustainable in a country where blacks outnumbered whites 22:1.[131] Under pressure from Vorster, Smith accepted in principle that white minority rule could not be maintained forever. He oversaw the 1979 general election which resulted in Abel Muzorewa, a politically moderate black bishop, being elected Prime Minister of the reconstituted Zimbabwe Rhodesia. Both ZANU and ZAPU had boycotted the election, which did not receive international recognition.[132] At the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting 1979, held in Lusaka, the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher surprised delegates by announcing that the UK would officially recognise the country's independence if it transitioned to democratic majority rule.[133]

.jpg.webp)

The negotiations took place at Lancaster House in London and were led by the Conservative Party politician Peter Carington.[134] Mugabe refused to attend these London peace talks,[135] opposing the idea of a negotiated rather than military solution to the Rhodesian War.[136] Machel insisted that he must, threatening to end Mozambican support for the ZANU-PF if he did not.[137] Mugabe arrived in London in September 1979.[138] There, he and Nkomo presented themselves as part of the "Patriotic Front" but established separate headquarters in the city.[139] At the conference the pair were divided in their attitude; Nkomo wanted to present himself as a moderate while Mugabe played up to his image as a Marxist revolutionary, with Carington exploiting this division.[140] Throughout the negotiations, Mugabe did not trust the British and believed that they were manipulating events to their own advantage.[141]

The ensuing Lancaster House Agreement called for all participants in the Rhodesian Bush War to agree to a ceasefire, with a British governor, Christopher Soames, arriving in Rhodesia to oversee an election in which the various factions could compete as political parties.[142] It outlined a plan for a transition to formal independence as a sovereign republic under black-majority rule, also maintaining that Rhodesia would be renamed Zimbabwe, a name adopted from the Iron Age archaeological site of Great Zimbabwe.[143] The agreement also ensured that the country's white minority retained many of its economic and political privileges,[144] with 20 seats to be reserved for whites in the new Parliament.[145] By insisting on the need for a democratic black majority government, Carington was able to convince Mugabe to compromise on the other main issue of the conference, that of land ownership.[146] Mugabe agreed to the protection of the white community's privately owned property on the condition that the UK and U.S governments provide financial assistance allowing the Zimbabwean government to purchase much land for redistribution among blacks.[147] Mugabe was opposed to the idea of a ceasefire, but under pressure from Machel he agreed to it.[148] Mugabe signed the agreement, but felt cheated,[148] remaining disappointed that he had never achieved a military victory over the Rhodesian forces.[149]

Electoral campaign: 1980

Returning to Salisbury in January 1980, Mugabe was greeted by a supportive crowd.[150] He settled into a house in Mount Pleasant, a wealthy white-dominated suburb.[151] Machel had cautioned Mugabe not to alienate Rhodesia's white minority, warning him that any white flight after the election would cause economic damage as it had in Mozambique.[152] Accordingly, during his electoral campaign, Mugabe avoided the use of Marxist and revolutionary rhetoric.[153] Mugabe insisted that in the election, ZANU would stand as a separate party to ZAPU, and refused Nkomo's request for a meeting.[154] He formed ZANU into a political party, known as Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU–PF).[155] Predictions were made that ZANU–PF would win the election on the basis of the country's ethnic divisions; Mugabe was Shona, a community that made up around 70% of the country's population, while Nkomo was Ndebele, a tribal group who made up only around 20%.[156] For many in the white community and in the British government, this outcome was a terrifying prospect due to Mugabe's avowed Marxist beliefs and the inflammatory comments that he had made about whites during the guerrilla war.[127]

During the campaign, Mugabe survived two assassination attempts.[157] In the first, which took place on 6 February, a grenade was thrown at his Mount Pleasant home, where it exploded against a garden wall.[157] In the second, on 10 February, a roadside bomb exploded near his motorcade as he left a Fort Victoria rally. Mugabe himself was unharmed.[157] Mugabe accused the Rhodesian security forces of being responsible for these attacks.[158] In an attempt to quell the possibility that Rhodesia's security forces would launch a coup to prevent the election, Mugabe met with Peter Walls, the commander of Rhodesia's armed forces, and asked him to remain in his position in the event of a ZANU–PF victory. At the time Walls refused.[159]

The electoral campaign was marred by widespread voter intimidation, perpetrated by Nkomo's ZAPU, Abel Muzorewa's United African National Council (UANC), and Mugabe's ZANU–PF.[160] Commenting on ZANU–PF's activities in eastern Rhodesia, Nkomo complained that "the word intimidation is mild. People are being terrorised. It is terror."[161] Reacting to ZANU–PF's acts of voter intimidation, Mugabe was called before Soames at Government House. Mugabe regarded the meeting as a British attempt to thwart his electoral campaign.[162] Under the terms of the negotiation, Soames had the power to disqualify any political party guilty of voter intimidation.[158] Rhodesia's security services, Nkomo, Muzorewa, and some of his own advisers all called on Soames to disqualify ZANU–PF. After deliberation, Soames disagreed, believing that ZANU–PF were sure to win the election and that disqualifying them would wreck any chance of an orderly transition of power.[158]

In the February election, ZANU–PF secured 63% of the national vote, gaining 57 of the 80 parliamentary seats allocated for black parties and providing them with an absolute majority.[163] ZAPU had gained 20 seats, and UANC had three.[156] Mugabe was elected MP for the Salisbury constituency of Highfield.[164] Attempting to calm panic and prevent white flight, Mugabe appeared on television and called for national unity, stability, and law and order, insisting that the pensions of white civil servants would be guaranteed and that private property would be protected.[165]

Prime Minister of Zimbabwe: 1980–1987

Southern Rhodesia gained internationally recognised independence on 18 April 1980. Mugabe took the oath of office as the newly minted country's first Prime Minister shortly after midnight.[167][168] He gave a speech at Salisbury's Rufaro Stadium announcing that Rhodesia would be renamed "Zimbabwe" and pledged racial reconciliation.[169] Soames aided Mugabe in bringing about an orderly transition of power; for this Mugabe remained grateful, describing Soames as a good friend.[170] Mugabe unsuccessfully urged Soames to remain in Zimbabwe for several more years,[171] and also failed to convince the UK to assume a two-year "guiding role" for his government because most ZANU–PF members lacked experience in governing.[172] ZANU–PF's absolute parliamentary majority allowed them to rule alone, but Mugabe created a government of national unity by inviting members of rival parties to join his cabinet.[173] Mugabe moved into the Premier's residence in Salisbury, which he left furnished in the same style as Smith had left it.[174]

Across the country, statues of Cecil Rhodes were removed and squares and roads named after prominent colonial figures were renamed after black nationalists.[175] In 1982 Salisbury was renamed Harare.[176] Mugabe employed North Korean architects to design Heroes' Acre, a monument and complex in western Harare to commemorate the struggle against minority rule.[177] Zimbabwe also received much aid from Western countries, whose governments hoped that a stable and prosperous Zimbabwe would aid the transition of South Africa away from apartheid and minority rule.[178] The United States provided Zimbabwe with a $25 million three-year aid package.[178] The UK financed a land reform program,[179] and provided military advisers to aid the integration of the guerrilla armies and old Rhodesian security forces into a new Zimbabwean military.[180] Members of both ZANLA and ZIPRA were integrated into the army; though, there remained a strong rivalry between the two groups.[181] As Prime Minister, Mugabe retained Walls as the head of the armed forces.[182]

Mugabe's government continued to make regular pronouncements about converting Zimbabwe into a socialist society, but did not take concrete steps in that direction.[183] In contrast to Mugabe's talk of socialism, his government's budgetary policies were conservative, operating within a capitalist framework and emphasising the need for foreign investment.[175] In office, Mugabe sought a gradual transformation away from capitalism and tried to build upon existing state institutions.[170] From 1980 to 1990, the country's economy grew by an average of 2.7% a year, but this was outstripped by population growth and real income declined.[184] The unemployment rate rose, reaching 26% in 1990.[184] The government ran a budget deficit year-on-year that averaged at 10% of the country's gross domestic product.[184] Under Mugabe's leadership, there was a massive expansion in education and health spending.[184] In 1980, Zimbabwe had just 177 secondary schools, by 2000 this number had risen to 1,548.[184] During that period, the adult literacy rate rose from 62% to 82%, one of the highest levels in Africa.[184] Levels of child immunisation were raised from 25% of the population to 92%.[184]

A new leadership elite were formed, who often expressed their newfound status through purchasing large houses and expensive cars, sending their children to private schools, and obtaining farms and businesses.[185] To contain their excesses, in 1984 Mugabe drew up a "leadership code" which prohibited any senior figures from obtaining more than one salary or owning over 50-acres of agricultural land.[185] There were exceptions, with Mugabe giving permission to General Solomon Mujuru to expand his business empire, resulting in him becoming one of the Zimbabwe's wealthiest people.[186] Growing corruption among the socio-economic elite generated resentment among the wider population, much of which was living in poverty.[187]

ZANU–PF also began establishing its own business empire, founding the M&S Syndicate in 1980 and the Zidoo Holdings in 1981.[186] By 1992, the party had fixed assets and businesses worth an estimated Z$500 million (US$75 million).[186] In 1980, ZANU–PF used Nigerian funds to set up the Mass Media Trust, through which they bought out a South African company that owned most of Zimbabwe's newspapers.[188] The white editors of these newspapers were sacked and replaced by government appointees.[189] These media outlets subsequently became a source of the party's propaganda.[189]

At independence, 39% of Zimbabwe's land was under the ownership of around 6000 white large-scale commercial farmers, while 4% was owned by black small-scale commercial farmers, and 41% was 'communal land' where 4 million people lived, often in overcrowded conditions.[190] The Lancaster House agreement ensured that until 1990, the sale of land could only take place on a "willing seller-willing buyer" basis. The only permitted exceptions were if the land was "underutilised" or needed for a public purpose, in which case the government could compulsorily purchase it while fully compensating the owner.[191] This meant that Mugabe's government was largely restricted to purchasing land which was of poor quality.[191] Its target was to resettle 18,000 black families on 2.5 million acres of white-owned land over three years. This would cost £30 million (US$60 million), half of which was to be provided by the UK government as per the Lancaster House Agreement.[190]

In 1986, Mugabe became chair of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), a position that he retained until 1989.[192] As the leader of one of the Front Line States, the countries bordering apartheid South Africa, he gained credibility within the anti-apartheid movement.[192]

Race relations

— Mugabe's speech after his 1980 victory[193]

Mugabe initially emphasised racial reconciliation and he was keen to build a good relationship with white Zimbabweans.[194] He hoped to avoid a white exodus and tried to allay fears that he would nationalise white-owned property.[195] He appointed two white ministers—David Smith and Denis Norman—to his government,[196] met with white leaders in agriculture, industry, mining, and commerce,[197] and impressed senior figures in the outgoing administration like Smith and Ken Flower with his apparent sincerity.[198] With the end of the war, petrol rationing, and economic sanctions, life for white Zimbabweans improved during the early years of Mugabe's rule.[199] In the economic boom that followed, the white minority—which controlled considerable property and dominated commerce, industry, and banking—were the country's main beneficiaries.[179]

Nevertheless, many white Zimbabweans complained that they were the victims of racial discrimination.[200] Many whites remained uneasy about living under the government of a black Marxist and they also feared that their children would be unable to secure jobs.[179] There was a growing exodus to South Africa, and in 1980, 17,000 whites—approximately a tenth of the white Zimbabwean population—emigrated.[180] Mugabe's government had pledged support for the African National Congress and other anti-apartheid forces within South Africa, but did not allow them to use Zimbabwe as a base for their military operations.[178] To protest apartheid and white minority rule in South Africa, Mugabe's government banned Zimbabwe from engaging South Africa in any sporting competitions.[178] In turn, South Africa tried to destabilise Zimbabwe by blocking trade routes into the country and supporting anti-Mugabe militants among the country's white minority.[201]

In December 1981, a bomb struck ZANU–PF headquarters, killing seven and injuring 124.[202] Mugabe blamed South African-backed white militants.[203] He criticised "reactionary and counter-revolutionary elements" in the white community, stating that despite the fact that they had faced no punishment for their past actions, they rejected racial reconciliation and "are acting in collusion with South Africa to harm our racial relations, to destroy our unity, to sabotage our economy, and to overthrow the popularly elected government I lead".[203] Increasingly he criticised not only the militants but the entire white community for holding a monopoly on "Zimbabwe's economic power".[204] This was a view echoed by many government ministers and the government-controlled media.[200] One of these ministers, Tekere, was involved in an incident in which he and seven armed men stormed a white-owned farmhouse, killing an elderly farmer; they alleged that in doing so they were foiling a coup attempt. Tekere was acquitted of murder; however, Mugabe dropped him from his cabinet.[205]

Racial mistrust and suspicion continued to grow.[206] In December 1981, the elderly white MP Wally Stuttaford was accused of being a South African agent, arrested, and tortured, generating anger among whites.[207] In July 1982, South African-backed white militants destroyed 13 aircraft at Thornhill. A number of white military officers were accused of complicity, arrested, and tortured. They were put on trial but cleared by judges, after which they were immediately re-arrested.[208] Their case generated an international outcry, which Mugabe criticised, stating that the case only gained such attention because the accused were white.[209] His defence of torture and contempt for legal procedures damaged his international standing.[210] White flight continued to grow, and within three years of Mugabe's premiership half of all white Zimbabweans had emigrated.[211] In the 1985 election, Smith's Conservative Alliance of Zimbabwe won 15 of the 20 seats allocated for white Zimbabweans.[212] Mugabe was outraged by this result,[213] lambasting white Zimbabweans for not repenting "in any way" by continuing to support Smith and other white politicians who had committed "horrors against the people of Zimbabwe".[212]

Relations with ZAPU and the Gukurahundi

Under the new constitution, Zimbabwe's Presidency was a ceremonial role with no governmental power; the first President was Canaan Banana.[214] Mugabe had previously offered the position to Nkomo, who had turned it down in favour of becoming Minister of Home Affairs.[215] While working together, there remained an aura of resentment and suspicion between Mugabe and Nkomo.[216] Mugabe gave ZAPU four cabinet seats, but Nkomo demanded more.[217] In contrast, some ZANU–PF figures argued that ZAPU should not have any seats in government, suggesting that Zimbabwe be converted into a one-party state.[218] Tekere and Enos Nkala were particularly adamant that there should be a crackdown on ZAPU.[218] After Nkala called for ZAPU to be violently crushed during a rally in Entumbane, street clashes between the two parties broke out in the city.[219]

In January 1981, Mugabe demoted Nkomo in a cabinet reshuffle; the latter warned that this would anger ZAPU supporters.[220] In February, violence between ZAPU and ZANU–PF supporters broke out among the battalion stationed at Ntabazinduna, soon spreading to other army bases, resulting in 300 deaths.[221] An arms cache featuring land mines and anti-aircraft missiles were then discovered at Ascot Farm, which was part-owned by Nkomo. Mugabe cited this as evidence that ZAPU were plotting a coup, an allegation that Nkomo denied.[222] Likening Nkomo to "a cobra in the house", Mugabe sacked him from the government, and ZAPU-owned businesses, farms, and properties were seized.[223]

Members of both ZANLA and ZIPRA had deserted their positions and engaged in banditry.[218] In Matabeleland, ZIPRA deserters who came to be known as "dissenters" engaged in robbery, holding up buses, and attacking farm houses, creating an environment of growing lawlessness.[224] These dissidents received support from South Africa through its Operation Mute, by which it hoped to further destabilise Zimbabwe.[225] The government often conflated ZIPRA with the dissenters,[226] although Nkomo denounced the dissidents and their South African supporters.[227] Mugabe authorised the police and army to crack down on the Matabeleland dissenters, declaring that state officers would be granted legal immunity for any "extra-legal" actions they may perform while doing so.[227] During 1982 he had established the Fifth Brigade, an elite armed force trained by the North Koreans; membership was drawn largely from Shona-speaking ZANLA soldiers and were answerable directly to Mugabe.[228] In January 1983, the Fifth Brigade were deployed in the region, overseeing a campaign of beatings, arson, public executions, and massacres of those accused of being sympathetic to the dissidents.[229] The scale of the violence was greater than that witnessed in the Rhodesian War.[230] Interrogation centres were established where people were tortured.[231] Mugabe acknowledged that civilians would be persecuted in the violence, claiming that "we can't tell who is a dissident and who is not".[232] The ensuing events became known as the "Gukurahundi", a Shona word meaning "wind that sweeps away the chaff before the rains".[233]

In 1984 the Gukurahundi spread to Matabeleland South, an area then in its third year of drought. The Fifth Brigade closed all stores, halted all deliveries, and imposed a curfew, exacerbating starvation for a period of two months.[234] The Bishop of Bulawayo accused Mugabe of overseeing a project of systematic starvation.[231] When a Roman Catholic delegation provided Mugabe with a dossier listing atrocities committed by the Fifth Brigade, Mugabe refuted all its allegations and accused the clergy of being disloyal to Zimbabwe.[235] He had the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace in Zimbabwe's suppressed.[236] In 1985, an Amnesty International report on the Gukurahundi was dismissed by Mugabe as "a heap of lies".[237] Over the course of four years, approximately 10,000 civilians had been killed, and many others had been beaten and tortured.[238] Genocide Watch later estimated that approximately 20,000 had been killed[239] and classified the events as genocide.[240]

Margaret Thatcher's UK government was aware of the killings but remained silent on the matter, cautious not to anger Mugabe and threaten the safety of white Zimbabweans.[241] The United States also did not raise strong objections, with President Ronald Reagan welcoming Mugabe to the White House in September 1983.[242] In October 1983, Mugabe attended the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in New Delhi, where no participating states mentioned the Gukurahundi.[242] In 2000, Mugabe acknowledged that the mass killings had happened, stating that it was "an act of madness ... it was wrong and both sides were to blame".[243] His biographer Martin Meredith argued that Mugabe and his ZANU–PF were solely to blame for the massacres.[243] Various Mugabe biographers have seen the Gukurahundi as a deliberate attempt to eliminate ZAPU and its support base to advance his desire for a ZANU–PF one-party state.[244]

There was further violence in the build-up to the 1985 election, with ZAPU supporters facing harassment from ZANU–PF Youth League brigades.[245] Despite this intimidation, ZAPU won all 15 of the parliamentary seats in Matabeleland.[245] Mugabe then appointed Enos Nkala as the new police minister. Nkala subsequently detained over 100 ZAPU officials, including five of its MPs and the Mayor of Bulawayo, banned the party from holding rallies or meetings, closed all of their offices, and dissolved all of the district councils that they controlled.[246] To avoid further violence, in December 1987 Nkomo signed a Unity Accord in which ZAPU was officially disbanded and its leadership merged into ZANU–PF.[247] The merger between the two parties left ZANU–PF with 99 of the 100 seats in parliament,[248] and established Zimbabwe as a de facto one-party state.[242]

President of Zimbabwe

Constitutional and economic reform: 1987–1995

In late 1987, Zimbabwe's parliament amended the constitution.[249] On 30 December it declared Mugabe to be executive President, a new position that combined the roles of head of state, head of government, and commander-in-chief of the armed forces.[250] This position gave him the power to dissolve parliament, declare martial law, and run for an unlimited number of terms.[251] According to Meredith, Mugabe now had "a virtual stranglehold on government machinery and unlimited opportunities to exercise patronage".[251] The constitutional amendments also abolished the twenty parliamentary seats reserved for white representatives,[252] and left parliament less relevant and independent.[253]

In the build-up to the 1990 election, parliamentary reforms increased the number of seats to 120; of these, twenty were to be appointed by the President and ten by the Council of Chiefs.[254] This measure made it more difficult for any opposition to Mugabe to gain a parliamentary majority.[255] The main opposition party in that election were the Zimbabwe Unity Movement (ZUM), launched in April 1989 by Tekere;[256] although a longstanding friend of Mugabe, Tekere accused him of betraying the revolution and establishing a dictatorship.[257] ZANU–PF propaganda made threats against those considering voting ZUM in the election; one television advert featured images of a car crash with the statement "This is one way to die. Another is to vote ZUM. Don't commit suicide, vote ZANU-PF and live."[258] In the election, Mugabe was re-elected President with nearly 80% of the vote, while ZANU–PF secured 116 of the 119 available parliamentary seats.[259]

Mugabe had long hoped to convert Zimbabwe into a one-party state, but in 1990 he officially "postponed" these plans as both Mozambique and many Eastern Bloc states transitioned from one-party states to multi-party republics.[260] Following the collapse of the Marxist-Leninist regimes in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, in 1991 ZANU–PF removed references to "Marxism-Leninism" and "scientific socialism" in its material; Mugabe maintained that "socialism remains our sworn ideology".[261] That year, Mugabe pledged himself to free market economics and accepted a structural adjustment programme provided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[262] This economic reform package called for Zimbabwe to privatise state assets and reduce import tariffs;[184] Mugabe's government implemented some but not all of its recommendations.[262] The reforms encouraged employers to cut their wages, generating growing opposition from the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions.[263]

By 1990, 52,000 black families had been settled on 6.5 million acres. This was insufficient to deal with the country's overcrowding problem, which was being exacerbated by the growth in the black population.[264] That year, Zimbabwe's parliament passed an amendment allowing the government to expropriate land at a fixed price while denying land-owners the right of appeal to the courts.[265] The government hoped that by doing so it could settle 110,000 black families on 13 million acres, which would require the expropriation of approximately half of all white-owned land.[265] Zimbabwe's Commercial Farmers Union argued that the proposed measures would wreck the country's economy, urging the government to instead settle landless blacks on the half-a-million acres of land that was either unproductive or state-owned.[266]

Concerns about the proposed measure—particularly its denial of the right to appeal—were voiced by the UK, US, and Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace.[265] The US, UK, International Monetary Fund, and World Bank threatened that if Zimbabwe implemented the law, it would forfeit foreign aid packages.[267] Responding to the criticisms, the government removed the ban on court appeals from the bill, which was then passed as law.[268] Over the following few years, hundreds of thousands of acres of largely white-owned land were expropriated.[269] In April 1994, a newspaper investigation found that not all of this was redistributed to landless blacks; much of the expropriated land was being leased to ministers and senior officials such as Witness Mangwede, who was leased a 3000-acre farm in Hwedza.[270] Responding to this scandal, in 1994 the UK government—which had supplied £44 million for land redistribution—halted its payments.[271]

In January 1992, Mugabe's wife died.[272] In April 1995, Horizon magazine revealed that Mugabe had secretly been having an affair with his secretary Grace Marufu since 1987 and that she had borne him a son and a daughter.[273] His secret revealed, Mugabe decided to hold a much-publicised wedding. 12,000 people were invited to the August 1996 ceremony, which took place in Kutama and was orchestrated by the head of the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Harare, Patrick Chakaipa.[274] The ceremony was controversial among the Catholic community because of the adulterous nature of Mugabe and Marufu's relationship.[275] To house his family, Mugabe then built a new mansion at Borrowdale.[276] In the 1995 parliamentary election—which saw a low turnout of 31.7%—ZANU–PF gained 147 out of 150 seats.[263] Following the election, Mugabe expanded his cabinet from 29 to 42 ministers while the government adopted a 133% pay rise for MPs.[277]

Economic decline: 1995–2000

— Mugabe biographer Martin Meredith[278]

Over the course of the 1990s, Zimbabwe's economy steadily deteriorated.[279] By 2000, living standards had declined from 1980; life expectancy was reduced, average wages were lower, and unemployment had trebled.[280] By 1998, unemployment was almost at 50%.[279] As of 2009, three to four million Zimbabweans—the greater part of the nation's skilled workforce—had left the country.[281] In 1997 there were growing demands for pensions from those who had fought for the guerrilla armies in the revolutionary war, and in August 1997 Mugabe put together a pension package that would cost the county Z$4.2 billion.[282] To finance this pension scheme, Mugabe's government proposed new taxes, but a general strike was called in protest in December 1997; amid protest from ZANU–PF itself, Mugabe's government abandoned the taxes.[283] In January 1998, riots about lack of access to food broke out in Harare; the army was deployed to restore order, with at least ten killed and hundreds injured.[284]

Mugabe increasingly blamed the country's economic problems on Western nations and the white Zimbabwean minority, who still controlled most of its commercial agriculture, mines, and manufacturing industry.[285] He called on supporters "to strike fear in the hearts of the white man, our real enemy",[280] and accused his black opponents of being dupes of the whites.[286] Amid growing internal opposition to his government, he remained determined to stay in power.[280] He revived the regular use of revolutionary rhetoric and sought to reassert his credentials as an important revolutionary leader.[287]

Mugabe also developed a growing preoccupation with homosexuality, lambasting it as an "un-African" import from Europe.[288] He described gay people as being "guilty of sub-human behaviour", and of being "worse than dogs and pigs".[289] This attitude may have stemmed in part from his strong conservative values, but it was strengthened by the fact that several ministers in the British government were gay. Mugabe began to believe that there was a "gay mafia" and that all of his critics were homosexuals.[290] Critics also accused Mugabe of using homophobia to distract attention from the country's problems.[288] In August 1995, he was due to open a human rights-themed Zimbabwe International Book Fair in Harare but refused to do so until a stall run by the group Gays and Lesbians of Zimbabwe was evicted.[291]

In 1996, Mugabe was appointed chair of the defence arm of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).[292] Without consulting parliament, in August 1998 he ordered Zimbabwean troops into the Democratic Republic of the Congo to side with President Laurent Kabila in the Second Congo War.[293] He initially committed 3000 troops to the operation; this gradually rose to 11,000.[293] He also persuaded Angola and Namibia to commit troops to the conflict.[293] Involvement in the war cost Zimbabwe an approximate US$1 million a day, contributing to its economic problems.[293] Opinion polls demonstrated that it was unpopular among Zimbabwe's population.[294] However, several Zimbabwean businesses profited, having been given mining and timber concessions and preferential trade terms in minerals from Kabila's government.[293]

In January 1999, 23 military officers were arrested for plotting a coup against Mugabe. The government sought to hide this, but it was reported by journalists from The Standard. The military subsequently illegally arrested the journalists and tortured them.[295] This brought international condemnation, with the EU and seven donor nations issuing protest notes.[296] Lawyers and human rights activists protested outside parliament until they were dispersed by riot police,[296] and the country's Supreme Court judges issued a letter condemning the military's actions.[297] In response, Mugabe publicly defended the use of extra-legal arrest and torture.[298]

.jpeg.webp)

In 1997, Tony Blair was elected Prime Minister of the UK after 18 years of Conservative rule. His Labour government expressed reticence toward restarting the land resettlement payments promised by the Lancaster House Agreement, with minister Clare Short rejecting the idea that the UK had any moral obligation to fund land redistribution.[299] This attitude fuelled anti-imperialist sentiment across Africa.[300] In October 1999, Mugabe visited Britain and in London, the human rights activist Peter Tatchell attempted to place him under citizen's arrest.[301] Mugabe believed that the British government had deliberately engineered the incident to embarrass him.[302] It further damaged Anglo-Zimbabwean relations,[302] with Mugabe expressing scorn for what he called "Blair and company".[303] In May 2000, the UK froze all development aid to Zimbabwe.[304] In December 1999, the IMF terminated financial support for Zimbabwe, citing economic mismanagement and widespread corruption as impediments to reform.[305]

To meet growing demand for constitutional reform, in April 1999 Mugabe's government appointed a 400-member Constitutional Commission to draft a new constitution which could be put to a referendum.[306] The National Constitutional Assembly—a pro-reform pressure group established in 1997—expressed concern that this commission was not independent of the government, noting that Mugabe had the power to amend or reject the draft.[307] The NCA called for the draft constitution to be rejected, and in a February 2000 referendum it was, with 53% against to 44% in favour; turnout was under 25%.[308] It was ZANU–PF's first major electoral defeat in twenty years.[309] Mugabe was furious, and blamed the white minority for orchestrating his defeat, referring to them as "enemies of Zimbabwe".[310]

Land seizures and growing condemnation: 2000–2008

The June 2000 parliamentary elections were Zimbabwe's most important since 1980.[311] Sixteen parties took part, and the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC)—led by trade unionist Morgan Tsvangirai—was particularly successful.[311] During the election campaign, MDC activists were regularly harassed and in some cases killed.[312] The Zimbabwe Human Rights Forum documented 27 murders, 27 rapes, 2466 assaults, and 617 abductions, with 10,000 people displaced by violence; the majority, but not all, of these actions were carried out by ZANU–PF supporters.[313] Observers from the European Union (EU) ruled that the election was neither free nor fair.[314] The vote produced 48% and 62 parliamentary seats for ZANU-PF and 47% and 57 parliamentary seats for the MDC.[315] For the first time, ZANU–PF were denied the two-thirds parliamentary majority required to push through constitutional change.[311] ZANU–PF had relied heavily on their support base in rural Shona-speaking areas, and retained only one urban constituency.[316]

In February 2000, land invasions began as armed gangs attacked and occupied white-owned farms.[317] The government referred to the attackers as "war veterans" but the majority were unemployed youth too young to have fought in the Rhodesian War.[317] Mugabe claimed that the attacks were a spontaneous uprising against white land owners, although the government had paid Z$20 million to Chenjerai Hunzvi's War Veterans Association to lead the land invasion campaign and ZANU–PF officials, police, and military figures were all involved in facilitating it.[318] Some of Mugabe's colleagues described the invasions as retribution for the white community's alleged involvement in securing the success of the 'no' vote in the recent referendum.[319] Mugabe justified the seizures by the fact that this land had been seized by white settlers from the indigenous African population in the 1890s.[320] He portrayed the invasions as a struggle against colonialism and alleged that the UK was trying to overthrow his government.[321] In May 2000, he issued a decree under the Presidential Powers (Temporary Measures) Act which empowered the government to seize farms without providing compensation, insisting that it was the British government that should make these payments.[322]

In March 2000, Zimbabwe's High Court ruled that the land invasions were illegal; they nevertheless continued,[323] and Mugabe began vilifying Zimbabwe's judiciary.[324] After the Supreme Court also backed this decision, the government called on its judges to resign, successfully pressuring Chief Justice Anthony Gubbay to do so.[325] ZANU–PF member Godfrey Chidyausiku was appointed to replace him, while the number of Supreme Court judges was expanded from five to eight; the three additional seats went to pro-Mugabe figures. The first act of the new Supreme Court was to reverse the previous declaration that the land seizures were illegal.[326] In November 2001, Mugabe issued a presidential decree permitting the expropriation of virtually all white-owned farms in Zimbabwe without compensation.[327] The farm seizures were often violent; by 2006 a reported sixty white farmers had been killed, with many of their employees experiencing intimidation and torture.[328] A large number of the seized farms remained empty, while many of those redistributed to black peasant-farmers were unable to engage in production for the market because of their lack of access to fertiliser.[329]

— Mugabe on the land seizures[330]

The farm invasions severely impacted agricultural development.[331] Zimbabwe had produced over two million tons of maize in 2000; by 2008 this had declined to approximately 450,000.[328] By October 2003, Human Rights Watch reported that half of the country's population were food insecure, lacking enough food to meet basic needs.[332] By 2009, 75% of Zimbabwe's population were relying on food aid, the highest proportion of any country at that time.[332] Zimbabwe faced continuing economic decline. In 2000, the country's GDP was US$7.4 billion; by 2005 this had declined to US$3.4 billion.[333] Hyperinflation resulted in economic crisis.[329] By 2007, Zimbabwe had the highest inflation rate in the world, at 7600%.[333] By 2008, inflation exceeded 100,000% and a loaf of bread cost a third of the average daily wage.[334] Increasing numbers of Zimbabweans relied on remittances from relatives abroad.[332]

Other sectors of society were negatively affected too. By 2005, an estimated 80% of Zimbabwe's population were unemployed,[335] and by 2008 only 20% of children were in schooling.[335] The breakdown of water supplies and sewage systems resulted in a cholera outbreak in late 2008, with over 98,000 cholera cases in Zimbabwe between August 2008 and mid-July 2009.[336] The ruined economy also impacted the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the country; by 2008 the HIV/AIDS rate for individuals aged between 15 and 49 was 15.3%.[337] In 2007, the World Health Organization declared the average life expectancy in Zimbabwe to be 34 for women and 36 for men, down from 63 and 54 respectively in 1997.[333] The country's lucrative tourist industry was decimated,[338] and there was a rise in poaching, including of endangered species.[338] Mugabe directly exacerbated this problem when he ordered the killing of 100 elephants to provide meat for an April 2007 feast.[338]

In October 2000, the MDC's MPs attempted to impeach Mugabe, but were thwarted by the Speaker of the House, Mugabe loyalist Emmerson Mnangagwa.[339] ZANU–PF increasingly equated itself with Zimbabwean patriotism,[340] with MDC supporters being portrayed as traitors and enemies of Zimbabwe.[341] The party presented itself as being on the progressive side of history, with the MDC representing a counter-revolutionary force that seeks to undermine the achievements of the ZANU–PF revolution and of decolonisation itself.[342] Mugabe claimed that the build-up to the 2002 presidential election represented "the third Chimurenga" and that it would set Zimbabwe free from its colonial heritage.[343] In the build-up to the election, the government changed the electoral rules and regulations to improve Mugabe's chances of victory.[344] New security legislation was introduced making it illegal to criticise the President.[344] The defence force commander, General Vitalis Zvinavashe, stated that the military would not recognise any election result other than a Mugabe victory.[345] The EU withdrew its observers from the country, stating that the vote was neither free nor fair.[345] The election resulted in Mugabe securing 56% of the vote to Tsvangirai's 42%.[346] In the aftermath of the election Mugabe declared that the state-owned Grain Marketing Board had the sole right to import and distribute grain, with the state distributors giving food to ZANU–PF supporters while withholding it from those suspected of backing the MDC.[347] In 2005, Mugabe instituted Operation Murambatsvina ("Operation Drive Out the Rubbish"), a project of forced slum clearance; a UN report estimated that 700,000 were left homeless. Since the inhabitants of the shantytowns overwhelmingly voted MDC, many alleged that the bulldozing was politically motivated.[348]

Mugabe's actions brought strong criticism. The Zimbabwe Council of Churches accused him of plunging the country into "a de facto state of warfare" to stay in power.[349] Several Southern African states remonstrated with him at a summit in Harare in September 2001.[350] In 2002, the Commonwealth expelled Zimbabwe from among its ranks; Mugabe blamed this on anti-black racism,[351] a view echoed by South Africa's President Thabo Mbeki.[352] Mbeki favoured a policy of "quiet diplomacy" in dealing with Mugabe,[353] and prevented the African Union (AU) from introducing sanctions against him.[354] The Africa-Europe Summit, scheduled to take place in Lisbon in April 2003, was deferred repeatedly because African leaders refused to attend while Mugabe was banned; it eventually took place in 2007 with Mugabe in attendance.[355] In 2004, the EU imposed a travel ban and asset freeze on Mugabe.[351] It extended these sanctions in 2008,[351] with the US government introducing further sanctions this same year.[356] The US and UK introduced a resolution at the UN Security Council calling for an arms embargo of Zimbabwe alongside an asset freeze and travel ban of Mugabe and other government figures; it was vetoed by Russia and China.[356] In 2009, the SADC demanded that Western states lift their targeted sanctions against Mugabe and his government.[352] ZANU–PF presented the sanctions as a form of Western neo-colonialism and blamed the West for Zimbabwe's economic problems.[357]

British prime minister Tony Blair allegedly planned regime change in Zimbabwe in the early 2000s as pressure intensified for Mugabe to step down.[358] British General Charles Guthrie, the Chief of the Defence Staff, revealed in 2007 that he and Blair had discussed the invasion of Zimbabwe.[359] However, Guthrie advised against military action: "Hold hard, you'll make it worse."[359] In 2013, South African President Thabo Mbeki said that Blair had also pressured South Africa to join in a "regime change scheme, even to the point of using military force" in Zimbabwe.[358] Mbeki refused because he felt that "Mugabe is part of the solution to this problem."[358] However, a spokesman for Blair said that "he never asked anyone to plan or take part in any such military intervention."[358]

Power-sharing with the opposition MDC: 2008–2013

In March 2008, the parliamentary and presidential elections were held. In the former, ZANU–PF secured 97 seats to the MDC's 99 and the rival MDC – Ncube's 9.[360][361] In May, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission announced the presidential vote results, confirming that Tsvangirai secured 47.9%, to Mugabe's 43.2%. As neither candidate secured 50%, a run-off vote was scheduled.[362] Mugabe saw his defeat as an unacceptable personal humiliation.[363] He deemed it a victory for his Western, and in particular British, detractors, whom he believed were working with Tsvangirai to end his political career.[363] ZANU–PF claimed that the MDC had rigged the election.[364]

After the election, Mugabe's government deployed its "war veterans" in a violent campaign against Tsvangirai supporters.[365] Between March and June 2008, at least 153 MDC supporters were killed.[366] There were reports of women affiliated with the MDC being subjected to gang rape by Mugabe supporters.[366] Tens of thousands of Zimbabweans were internally displaced by the violence.[366] These actions brought international condemnation of Mugabe's government. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon expressed concern about the violence,[367] which was also unanimously condemned by the UN Security Council, which declared that a free and fair election was "impossible".[367] 40 senior African leaders—among them Desmond Tutu, Kofi Annan, and Jerry Rawlings—signed an open letter calling for an end to the violence.[368]

In response to the violence, Tsangirai pulled out of the run-off.[214] In the second round, Mugabe was pronounced victor with 85.5% of the vote, and immediately re-inaugurated as President.[369][370] The SADC oversaw the establishment of a power-sharing agreement; brokered by Mbeke, it was signed in September 2008.[371] Under the agreement, Mugabe remained President while Tsvangirai became Prime Minister and the MDC's Arthur Mutambara became Vice Prime Minister. The cabinet was equally divided among MDC and ZANU–PF members. ZANU–PF nevertheless displayed unwillingness to share power,[372] and were anxious to prevent any sweeping political changes.[373] Under the power-sharing agreement, a number of limited reforms were passed.[374] In early 2009, Mugabe's government declared that—to combat rampant inflation—it would recognise U.S. dollars as legal tender and would pay government employees in this currency.[336] This helped to stabilise prices.[336] ZANU–PF blocked many of the proposed reforms and a new constitution was passed in March 2013.[374]

Later years: 2013–2017

Declaring that he would "fight like a wounded animal" for re-election,[363] Mugabe approached the 2013 elections believing that it would be his last.[375] He hoped that a decisive electoral victory would secure his legacy, signal his triumph over his Western critics, and irreparably damage Tsvangirai's credibility.[375] The opposition parties believed that this election was their best chance for ousting Mugabe.[376] They portrayed him as a feeble old man who was being told what to do by the military;[377] at least one academic observer argued that this was untrue.[377]

In contrast to 2008, there was no organised dissent against Mugabe within ZANU–PF.[378] The party elite decided to avoid the violence that had marred the 2008 election so as not to undermine its credibility,[374] particularly in the eyes of the SADC, thus allowing Zimbabwe's government to consolidate its rule without interference.[374] Mugabe called upon supporters to avoid violence,[374] and attended far fewer rallies than in past elections, in part because of his advanced age and in part to ensure that those rallies he did attend were larger.[379] The ZANU–PF offered gifts, including food and clothing, to many members of the electorate to encourage them to vote for the party.[380]

ZANU–PF won a landslide victory, with 61% of the presidential vote and over two-thirds of parliamentary seats.[381] The elections were not considered free and fair; there were widespread stories of vote rigging and many voters may have been fearful of the violence that had surrounded the 2008 election.[381] During the campaign, many MDC supporters had remained quiet about their views out of fear of reprisals.[382] The MDC was also negatively impacted by its time in the coalition government, with perceptions that it had been just as corrupt as ZANU–PF.[383] ZANU–PF had also capitalised on its appeals to African race, land, and liberation, while the MDC was often associated with white farmers, Western nations, and perceived Western values such as LGBT rights.[384]

In February 2014, Mugabe underwent a cataract operation in Singapore; on return he celebrated his ninetieth birthday at a Marondera football stadium.[385] In December 2014, Mugabe fired his Vice-President, Joice Mujuru, accusing her of plotting his overthrow.[386] In January 2015, Mugabe was elected as the Chairperson of the African Union (AU).[387] In November 2015, he announced his intention to run for re-election as Zimbabwe's President in 2018, at the age of 94, and was accepted as the ZANU–PF candidate.[388] In February 2016, Mugabe said he had no plans for retirement and would remain in power "until God says 'come'".[389] In February 2017, right after his 93rd birthday, Mugabe stated he would not retire nor pick a successor, even though he said he would let his party choose a successor if it saw fit.[390][391] In May 2017, Mugabe took a weeklong trip to Cancún, Mexico, ostensibly to attend a three-day conference on disaster risk reduction, eliciting criticism of wasteful spending from opposition figures.[392][393] He made three medical trips to Singapore in 2017, and Grace Mugabe called on him to name a successor.[394]

In October 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) appointed Mugabe as a goodwill ambassador; this attracted criticism from both the Zimbabwean opposition and various foreign governments given the poor state of the Zimbabwean health system.[395] Responding to the outcry, WHO revoked Mugabe's appointment a day later.[396] In response, foreign minister Walter Mzembi said the United Nations system should be reformed.[397]

Coup d'état and resignation: 2017

On 6 November 2017, Mugabe sacked his first vice-president, Emmerson Mnangagwa. This fueled speculation that he intended to name Grace his successor. Grace was very unpopular with the ZANU–PF old guard. On 15 November 2017, the Zimbabwe National Army placed Mugabe under house arrest at his Blue Roof mansion as part of what it described as an action against "criminals" in Mugabe's circle.[398][399][400]

On 19 November, he was sacked as leader of ZANU–PF, and Mnangagwa was appointed in his place.[401] The party also gave Mugabe an ultimatum: resign by noon the following day, or it would introduce an impeachment resolution against him. In a nationally televised speech that night, Mugabe refused to say that he would resign.[402] In response, ZANU–PF deputies introduced an impeachment resolution on 21 November 2017, which was seconded by the MDC–T.[403] The constitution stipulated that removing a president from office required a two-thirds majority of both the House of Assembly and Senate in a joint sitting. However, with both major parties supporting the motion and controlling all but six seats in both houses between them (all but four in the lower house and all but two in the upper house), Mugabe's impeachment and removal appeared all but certain.

As per the constitution, both chambers met in joint session to debate the resolution. Hours after the debate began, the Speaker of the House of Assembly read a letter from Mugabe announcing that he had resigned, effective immediately.[404] Mugabe and his wife negotiated a deal before his resignation, under which he and his kin were exempted from prosecution, his business interests would remain untouched, and he would receive a payment of at least $10 million.[405][406] In July 2018, the Zimbabwe Supreme Court ruled that Mugabe had resigned voluntarily, despite some of the ex-president's subsequent comments.[407]

Post-presidency

Late in December 2017, according to a government gazette, Mugabe was given full diplomatic status and, out of public funds, a five-bedroom house, up to 23 staff members, and personal vehicles. He further was permitted to keep the business interests and other wealth which he had amassed while in power, and he received an additional payment of about ten million dollars.[408]

On 15 March 2018, in his first interview since removal from the presidency, Mugabe insisted that he had been ousted in a "coup d'état" which must be undone. He stated that he would not work with Mnangagwa and termed Mnangagwa's presidency "illegal" and "unconstitutional".[409] In a lawsuit brought by two political parties, the Liberal Democrats and the Revolutionary Freedom Fighters, and others, the court found that the resignation was legal, and that Mnangagwa, as vice-president, duly took over the presidency.[407]

The state media reported that Mugabe had backed the National Political Front, which was formed by Ambrose Mutinhiri, a former high-ranking ZANU-PF politician who resigned in protest against Mugabe's removal from the presidency. The NPF posted a picture of Mutinhiri posing with Mugabe[410] and issued a press release in which it said that the former president had praised the decision.[411]

On the eve of the 29 July 2018 general election, the first in 38 years in which he would not be a candidate, Mugabe held a surprise press conference, in which he stated that he would not vote for President Mnangagwa and ZANU–PF, the party he founded. Instead, he intended to vote for Nelson Chamisa, the candidate for his long-time rivals, the MDC.[412][413][414][415]

Illness, death and funeral: 2019