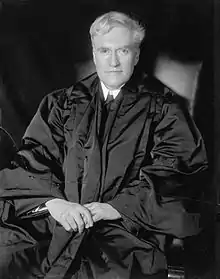

Benjamin N. Cardozo

Benjamin Nathan Cardozo (May 24, 1870 – July 9, 1938) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Previously, he had served as the Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals. Cardozo is remembered for his significant influence on the development of American common law in the 20th century, in addition to his philosophy and vivid prose style.

Benjamin N. Cardozo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office March 2, 1932 – July 9, 1938[1] | |

| Nominated by | Herbert Hoover |

| Preceded by | Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Felix Frankfurter |

| Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals | |

| In office January 1, 1927 – March 7, 1932 | |

| Preceded by | Frank Hiscock |

| Succeeded by | Cuthbert Pound |

| Associate Judge of the New York Court of Appeals | |

| In office January 15, 1917 – December 31, 1926 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel Seabury |

| Succeeded by | John F. O'Brien |

| Justice of the Supreme Court of New York for the First Judicial Division | |

| In office January 5, 1914 – January 15, 1917 (Sitting by designation in the Court of Appeals from February 2, 1914) | |

| Preceded by | Bartow S. Weeks |

| Succeeded by | Samuel H. Ordway |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Benjamin Nathan Cardozo May 24, 1870 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | July 9, 1938 (aged 68) Port Chester, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Father | Albert Cardozo |

| Education | Columbia University (BA, MA) |

Born in New York City, Cardozo passed the bar in 1891 after attending Columbia Law School. He won an election to the New York Supreme Court in 1913 but joined the New York Court of Appeals the following year. He won election as Chief Judge of that court in 1926. As Chief Judge, he wrote majority opinions on cases such as Palsgraf v. Long Island Railroad Co.

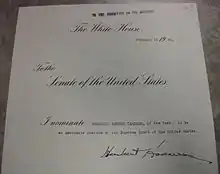

In 1932, President Herbert Hoover appointed Cardozo to the Supreme Court to succeed Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Cardozo served on the Court until his death in 1938, and formed part of the liberal bloc of justices known as the Three Musketeers. He wrote the Court's majority opinion in notable cases such as Nixon v. Condon and Steward Machine Co. v. Davis.

Early life and career

Early life and family

Cardozo, the son of Rebecca Washington (née Nathan) and Albert Jacob Cardozo,[2] was born in 1870 in New York City. Both Cardozo's maternal grandparents, Sara Seixas and Isaac Mendes Seixas Nathan, and his paternal grandparents, Ellen Hart and Michael H. Cardozo, were Western Sephardim of the Portuguese Jewish community, and affiliated with Manhattan's Congregation Shearith Israel. Their ancestors had immigrated to the British colonies from London, England before the American Revolution.

The family were descended from Jewish-origin New Christian conversos. They left the Iberian Peninsula for Holland during the Inquisition.[2] There they returned to the practice of Judaism. Cardozo family tradition held that their marrano (New Christians who maintained crypto-Jewish practices in secrecy) ancestors were from Portugal,[2] although Cardozo's ancestry has not been firmly traced to that country.[3] But "Cardozo" (archaic spelling of Cardoso), "Seixas" and "Mendes" are the Portuguese, rather than Spanish, spelling of those common Iberian surnames.

Benjamin Cardozo had a fraternal twin, his sister Emily. There were four other siblings, including an older sister Nell and older brother.

Benjamin was named for his uncle, Benjamin Nathan, a vice president of the New York Stock Exchange. He was murdered in 1870 and the case was never solved.[4] Among their many cousins, given their deep history in the US, was the poet Emma Lazarus. Other earlier relations include Francis Lewis Cardozo (1836-1903), Thomas Cardozo, and Henry Cardozo, free men of color of Charleston, South Carolina. Francis became a Presbyterian minister in New Haven, Connecticut after education in Scotland, and was elected as Secretary of State of South Carolina during the Reconstruction era. Later he worked as an educator in Washington, DC under a Republican administration.[5]

Albert Cardozo, Benjamin Cardozo's father, was a judge on the Supreme Court of New York (the state's general trial court) until 1868. He was implicated in a judicial corruption scandal, sparked by the Erie Railway takeover wars, and forced to resign. The scandal also led to the creation of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York. After leaving the court, the senior Cardozo practiced law for nearly two decades more until his death in 1885.

When Benjamin and Emily were young, their mother Rebecca died. The twins were raised during much of their childhood largely by their sister Nell, who was 11 years older. Benjamin remained devoted to her throughout his life. One of Benjamin's tutors was Horatio Alger.[6]

Education

At age 15, Cardozo entered Columbia University[6] where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.[7] He was admitted to Columbia Law School in 1889. Cardozo wanted to enter a profession that could enable him to support himself and his siblings, but he also hoped to restore the family name, sullied by his father's actions as a judge. Cardozo left law school after two years without a law degree.[8] [9]

Legal practice

Cardozo passed the bar in 1891 and began practicing appellate law alongside his older brother.[6] Benjamin Cardozo practiced law in New York City until year-end 1913 with Simpson, Warren and Cardozo.[6][10]

Interested in advancement and restoring the family name, Cardozo ran for a judgeship on the New York Supreme Court. In November 1913, Cardozo was elected by a large margin to a 14-year term on that court, taking office on January 1, 1914.

New York Court of Appeals

In February 1914, Cardozo was designated to the New York Court of Appeals under the Amendment of 1899.[11] He was reportedly the first Jew to serve on the Court of Appeals.

In January 1917, he was appointed by the governor to a regular seat on the Court of Appeals to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Samuel Seabury. In November 1917, he was elected on the Democratic and Republican tickets to a 14-year term on the Court of Appeals.

In 1926, he was elected, on both tickets again, to a 14-year term as Chief Judge. He took office on January 1, 1927, and resigned on March 7, 1932 to accept an appointment to the United States Supreme Court.

His tenure was marked by a number of original rulings, in tort and contract law in particular. This is partly due to timing; rapid industrialization was forcing courts to look anew at old common law components to adapt to new settings.[6]

In 1921, Cardozo gave the Storrs Lectures at Yale University, which were later published as The Nature of the Judicial Process (On line version), a book that remains valuable to judges today.[6] Shortly thereafter, Cardozo became a member of the group that founded the American Law Institute, which crafted a Restatement of the Law of Torts, Contracts, and a host of other private law subjects. He wrote three other books that also became standards in the legal world.[6]

While on the Court of Appeals, he criticized the Exclusionary rule as developed by the federal courts, saying: "The criminal is to go free because the constable has blundered." He noted that many states had rejected the rule, but suggested that the adoption by the federal courts would affect the practice in the sovereign states.[12][13][14][15]

United States Supreme Court

In 1932, President Herbert Hoover appointed Cardozo to the Supreme Court of the United States to succeed Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. The New York Times said of Cardozo's appointment that "seldom, if ever, in the history of the Court has an appointment been so universally commended."[16] Democratic Cardozo's appointment by a Republican president has been referred to as one of the few Supreme Court appointments in history that was not motivated by partisanship or politics, but strictly based on the nominee's contribution to law.[17] At the time Hoover was running for re-election, eventually against Democrat Franklin Roosevelt, so he may still have been considering a larger political calculation.

Cardozo was confirmed by a unanimous voice vote in the Senate on February 24.[18] On a radio broadcast on March 1, 1932, the day of Cardozo's confirmation, Clarence C. Dill, Democratic Senator for Washington, called Hoover's appointment of Cardozo "the finest act of his career as President".[19] The entire faculty of the University of Chicago Law School had urged Hoover to nominate Cardozo, as did the deans of the law schools at Harvard, Yale, and Columbia. Justice Harlan Fiske Stone strongly urged Hoover to name Cardozo, even offering to resign to make room for him if Hoover had his heart set on someone else (Stone had suggested to Calvin Coolidge that he should nominate Cardozo in 1925 before Stone).[20] Hoover originally demurred; he was concerned that there were already two justices from New York, and a Jew on the court. Justice James McReynolds was known as a notorious anti-Semite. When the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, William E. Borah of Idaho, added his strong support for Cardozo, however, Hoover finally bowed to the pressure.

Cardozo was a member of the Three Musketeers, along with Brandeis and Stone, who were considered to be the liberal faction of the Supreme Court. In his years as an Associate Justice, Cardozo wrote opinions that stressed the necessity for the tightest adherence to the Tenth Amendment.

Death

In late 1937, Cardozo had a heart attack, and in early 1938, he suffered a stroke. He died on July 9, 1938, at the age of 68. He was buried in Beth Olam Cemetery in Queens.[21][22]

Honors

Cardozo received the honorary degree of LL.D. from several colleges and universities, including: Columbia (1915); Yale (1921); New York (1922); Michigan (1923); Harvard (1927); St. John's (1928); St. Lawrence (1932); Williams (1932); Princeton (1932); Pennsylvania (1932); Brown (1933); and Chicago (1933).[23]

Personal life

As an adult, Cardozo no longer practiced Judaism (he identified as an agnostic), but he was proud of his Jewish heritage.[24]

Of the six children born to Albert and Rebecca Cardozo, only his twin sister Emily married. She and her husband did not have any children.

Constitutional law scholar Jeffrey Rosen noted in a The New York Times Book Review of Richard Polenberg's book on Cardozo:

Polenberg describes Cardozo's lifelong devotion to his older sister Nell, with whom he lived in New York until her death in 1929. When asked why he had never married, Cardozo replied, quietly and sadly, "I never could give Nellie the second place in my life."

Ethnicity

Cardozo was the second Jewish justice to be appointed to the Supreme Court. The first was Louis Brandeis, whose family was Ashkenazi.

Cardozo was born into the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish community, which had traditions distinct from the Ashkenazi. Since the appointment of Justice Sonia Sotomayor in the 21st century, some commentators have suggested that Cardozo should be considered the 'first Hispanic justice.' But he did not grow up in Hispanic culture. In 1492 the Spanish Crown expelled resident Jews who would not convert, and persecuted some who did.[25][26][27]

In response to this controversy, Cardozo biographer Kaufman questioned the usage of the term "Hispanic" in Justice Cardozo's lifetime, stating: "Well, I think he regarded himself as a Sephardic Jew whose ancestors came from the Iberian Peninsula."[28] After centuries in British North America, Cardozo "confessed in 1937 that his family preserved neither the Spanish language nor Iberian cultural traditions".[29] Ancestors had lived in England, the British colonies, and the United States since the 17th century.

Some Latino advocacy groups, such as the National Association of Latino Elected Officials and the Hispanic National Bar Association, consider Sonia Sotomayor to be the first Hispanic justice, as she was raised in Hispanic culture.[25][28]

Cases

- New York Courts

- Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospital, 105 N.E. 92 (1914) it is necessary to get informed consent from a patient before operation, but a non-profit hospital was not vicariously liable (the latter aspect was reversed in 1957)

- MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co., 111 N.E. 1050 (1916) ending privity as a prerequisite to duty in product liability by ruling that manufacturers of products could be held liable for injuries to consumers regardless of lack of privity.

- De Cicco v. Schweizer, 117 N.E. 807 (1917) where Cardozo approached the issue of third party beneficiary law in a contract for marriage case.

- Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon, 118 N.E. 214 (1917) on an implied promise to do something constituting consideration in a contract.

- Martin v. Herzog, 126 N.E. 814 (1920) breach of statutory duty establishes negligence, and the elements of the claim includes proof of causation

- Jacob & Youngs v. Kent, 230 N.Y. 239 (1921), substantial performance of a contract does not lead to a right to terminate, only damages.

- Hynes v. New York Central Railroad Company, 131 N.E. 898 (1921), a railway owed a duty of care despite the victims being trespassers.

- Glanzer v Shepard, 233 N.Y. 236, 135 N.E. 275, 23 A.L.R. 1425 (1922), a Caballero bean weighing dispute, with duties imposed by law but growing out of contract

- Berkey v. Third Avenue Railway, 244 N.Y. 84 (1926), the corporate veil cannot be pierced, even in favor of a tort victim unless domination of a subsidiary by the parent is complete.

- Wagner v. International Railway, 232 N.Y. 176 (1926) the rescue doctrine. "Danger invites rescue. The cry of distress is the summons to relief [...] The emergency begets the man. The wrongdoer may not have foreseen the coming of a deliverer. He is accountable as if he had."

- Meinhard v. Salmon, 164 N.E. 545 (1928) the fiduciary duty of business partners is, "Not honesty alone, but the punctilio of an honor the most sensitive."

- Palsgraf v. Long Island Rail Road Co., 162 N.E. 99 (1928) the development of the concept of the proximate cause in tort law.

- Jessie Schubert v. August Schubert Wagon Company, 164 N.E. 42 (1929) Respondeat superior and spousal immunity relationship are not related.

- Murphy v. Steeplechase Amusement Park, 166 N.E. 173 (1929) denied a right to recover for knee injury from riding "The Flopper" funride since the victim "assumed the risk."

- Ultramares v. Touche, 174 N.E. 441 (1931) on the limitation of liability of auditors

- US Supreme Court

- Nixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73 (1932) all white Texas Democratic Party unconstitutional

- Welch v. Helvering, 290 U.S. 111 (1933) which concerns Internal Revenue Code Section 162 and the meaning of "ordinary" business deductions.

- Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan, 293 U.S. 388 (1935) dissenting from a narrow interpretation of the Commerce Clause.

- A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495 (1935), concurring in the invalidation of poultry regulations as outside the commerce clause power.

- Carter v. Carter Coal Company, 298 U.S. 238 (1936) dissenting over the scope of the Commerce Clause.

- Steward Machine Company v. Davis, 301 U.S. 548 (1937) unemployment compensation and social security were constitutional

- Helvering v. Davis, 301 U.S. 619 (1937) social security not a contributory programme

- Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319 (1937) the due process clause incorporated those rights which were "implicit in the concept of ordered liberty."

In his own words

Cardozo's opinion of himself shows some of the same flair as his legal opinions:

In truth, I am nothing but a plodding mediocrity—please observe, a plodding mediocrity—for a mere mediocrity does not go very far, but a plodding one gets quite a distance. There is joy in that success, and a distinction can come from courage, fidelity and industry.[30]

Schools, organizations, and buildings named after Cardozo

- Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University in New York City

- Cardozo College, a dormitory building at Stony Brook University in Stony Brook, New York

- Benjamin N. Cardozo Lodge #163, Knights of Pythias[31]

- Benjamin N. Cardozo High School in the borough of Queens in New York City

- The Cardozo Hotel in Miami in Miami, Florida, on 1300 Ocean Drive

.jpg.webp) Cardozo Hotel (Miami Beach)

Cardozo Hotel (Miami Beach)

Bibliography

- Cardozo, Benjamin N. (1921), The Nature of the Judicial Process, The Storrs Lectures Delivered at Yale University.

- Cardozo, Benjamin N. (1924), The Growth of the Law, 5 Additional Lectures Delivered at Yale University.

- Cardozo, Benjamin N. (1928). The Paradoxes of Legal Science. Columbia University. OCLC 843833.

- Cardozo, Benjamin N. (1931), Law and Literature and Other Essays and Addresses.

- Cardozo, Benjamin N. (1889), The Altruist in Politics, commencement oration at Columbia College, Gutenberg Project version.

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Hughes Court

Notes

- "Federal Judicial Center: Benjamin Cardozo". 2009-12-12. Archived from the original on 2009-05-14. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- Kaufman, Andrew L. (1998). Cardozo. Harvard University Press. pp. 6–9. ISBN 0-674-09645-2.

- Mark Sherman, 'First Hispanic justice? Some say it was Cardozo', The Associated Press, 2009.

- Pearson, Edmund L. (1999). "The Twenty-Third Street Murder". Studies in Murder. Ohio State University Press. pp. 123–164. ISBN 081425022X.

- Richardson, Joe M. "Francis L. Cardozo: Black educator during reconstruction." Journal of Negro Education 48.1 (1979): 73–83. in JSTOR

- Christopher L. Tomlins (2005). The United States Supreme Court. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 467. ISBN 978-0-618-32969-4. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- Supreme Court Justices Who Are Phi Beta Kappa Members Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, Phi Beta Kappa website. Retrieved Oct 4, 2009

- Levy, Beryl Harold (November 2007). "Realist Jurisprudence and Prospective Overruling". New York Review of Books. LIV (17): 10, n. 31.

- "Cardozo, Benjamin N". Great American Judges: An Encyclopedia. 155: ABC-CLIO. 2003.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Pollak, Louis H. (2009). "Pollak, Walter Heilprin (1887–1941)". In Newman, Roger K. (ed.). The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law. Yale University Press. p. 430. ISBN 978-0300113006. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- Designation, The New York Times, February 3, 1914

- People of the State of New York v. John Defore, 150 N.E. 585 (1926).

- Stagg, Tom, Judge, United States District Court Western District of Louisiana (July 15, 1991). "Letter to the Editor". The New York Times. Shreveport, La. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- Spence, Karl (2006). "Fair or Foul? Exclusionary rule hurts the innocent by protecting the guilty". Yo! Liberals! You Call This Progress?. Converse, Texas: Chattanooga Free Press/Fielding Press. ISBN 0976682605. Retrieved January 7, 2013. ISBN 978-0976682608.

- Polenberg, Richard (1997). The World of Benjamin Cardozo: Personal Values and the Judicial Process. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 203–207. ISBN 0674960521. Retrieved January 13, 2012. ISBN 978-0674960527

- "Cardozo is named to Supreme Court". The New York Times. 1932-02-16.

- James Taranto, Leonard Leo (2004). Presidential Leadership. Wall Street Journal Books. ISBN 978-0-7432-7226-1. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- (The New York Times, February 25, 1932, p. 1)

- (The New York Times, March 2, 1932, p. 13)

- (Handler, 1995)

- "Christensen, George A. (1983) Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices, Yearbook". Archived from the original on 2005-09-03. Retrieved 2013-11-24.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Supreme Court Historical Society at Internet Archive.

- See also, Christensen, George A., Here Lies the Supreme Court: Revisited, Journal of Supreme Court History, Volume 33 Issue 1, Pages 17 – 41 (19 Feb 2008), University of Alabama.

- Death Notices: Supplement to General Alumni Catalog. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan. 1939. p. 16.

- Benjamin Cardozo., Jewish Virtual Library,

- "'Cardozo was first, but was he Hispanic?,' USA Today, May 27, 2009". May 27, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- "Mark Sherman, 'First Hispanic Justice? Some Say It Was Cardozo,' Associated Press May 26, 2009". Archived from the original on August 21, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- "Robert Schlesinger, Would Sotomayor be the First Hispanic Supreme Court Justice or Was it Cardozo? US News & World Report May 29, 2009".

- "Neil A. Lewis, 'Was a Hispanic Justice on the Court in the '30s?,' The New York Times, May 26, 2009". The New York Times. May 27, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- Aviva Ben-Ur (2009). Sephardic Jews in America: A Diasporic History. New York: NYU Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-8147-8632-1.

- As quoted in Nine Old Men (1936) by Drew Pearson and Robert Sharon Allen, p. 221.

- * * * Benjamin N. Cardozo Lodge at www.cardozospeaks.org

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1999). Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Clinton (Revised ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-9604-9.

- Cardozo, Benjamin N. (1957). An Introduction to Law. Cambridge: Harvard Law Review Association. (Chapters by eight distinguished American judges).

- Cunningham, Lawrence A. (1995). "Cardozo and Posner: A Study in Contracts". William & Mary Law Review. 36: 1379. SSRN 678761.

- Cardozo, Benjamin N. [1870–1938]. Essays Dedicated to Mr. Justice Cardozo. [N.p.]: Published by Columbia Law Review, Harvard Law Review, Yale Law Journal, 1939. [143] pp. Contributors: Harlan Fiske Stone, the Rt. Hon. Lord Maugham, Herbert Vere Evatt, Learned Hand, Irving Lehman, Warren Seavey, Arthur L. Corbin, Felix Frankfurter. Also includes a reprint of Cardozo's essay "Law And Literature" with a foreword by James M. Landis.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Frankfurter, Felix, Mr. Justice Cardozo and Public Law, Columbia Law Review 39 (1939): 88–118, Harvard Law Review 52 (1939): 440–470, Yale Law Journal 48 (1939): 458–488.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Handler, Milton (1995). "Stone's Appointment by Coolidge". The Supreme Court Historical Society Quarterly. 16 (3): 4.

| External video | |

|---|---|

- Kaufman, Andrew L. (1998). Cardozo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-09645-2.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Polenberg, Richard (1997). The World of Benjamin Cardozo: Personal Values and the Judicial Process. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 320. ISBN 978-0-674-96051-0.

- Posner, Richard A. (1990). Cardozo: A Study in Reputation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-67555-6.

- Seavey, Warren A., Mr. Justice Cardozo and the Law of Torts, Columbia Law Review 39 (1939): 20–55, Harvard Law Review 52 (1939): 372–407, Yale Law Journal 48 (1939): 390–425

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

External links

- Benjamin Nathan Cardozo at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Works by Benjamin Nathan Cardozo at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Benjamin N. Cardozo at Internet Archive

- Works by Benjamin N. Cardozo at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Benjamin N. Cardozo at Find a Grave

- Benjamin Cardozo at Michael Ariens.com.

- History of the Court, the Hughes Court at Supreme Court Historical Society.

- Listing and portrait of Benjamin N. Cardozo, New York Court of Appeals judge at Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York.

- Oyez Project, U.S. Supreme Court media, Benjamin N. Cardozo.

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Frank Hiscock |

Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals 1927–1932 |

Succeeded by Cuthbert Pound |

| Preceded by Oliver Holmes |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1932–1938 |

Succeeded by Felix Frankfurter |