Neil Gorsuch

Neil McGill Gorsuch (/ˈɡɔːrsʌtʃ/ GOR-sutch;[1] born August 29, 1967) is an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.[2] He was nominated by President Donald Trump on January 31, 2017 and has served since April 10, 2017.[3][4]

Neil Gorsuch | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2017 | |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| Assumed office April 10, 2017 | |

| Nominated by | Donald Trump |

| Preceded by | Antonin Scalia |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit | |

| In office August 8, 2006 – April 9, 2017 | |

| Nominated by | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | David M. Ebel |

| Succeeded by | Allison H. Eid |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Neil McGill Gorsuch August 29, 1967 Denver, Colorado, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) | Louise Burleston (m. 1996) |

| Children | 2 |

| Parents | David Gorsuch Anne Gorsuch Burford |

| Education | |

Gorsuch was born and spent his early life in Denver, Colorado, then lived in Bethesda, Maryland, while attending prep school. He earned a Bachelor of Arts from Columbia University, a Juris Doctor from Harvard University, and after practicing law for 15 years received a Doctor of Philosophy degree in Law from the University of Oxford, where his doctoral thesis concerned the morality of assisted suicide, under the supervision of the Catholic legal philosopher John Finnis.[5][6]

From 1995 to 2005, Gorsuch was in private practice with the law firm of Kellogg, Hansen, Todd, Figel & Frederick. Gorsuch was Principal Deputy Associate Attorney General at the United States Department of Justice from 2005 until his appointment to the Tenth Circuit. Gorsuch was nominated to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit by President George W. Bush on May 10, 2006, to replace Judge David M. Ebel, who took senior status in 2006.

Gorsuch is a proponent of textualism in statutory interpretation and originalism in interpreting the United States Constitution.[7][8][9] Along with Justice Clarence Thomas, he is an advocate of natural law jurisprudence.[10] Gorsuch clerked for Judge David B. Sentelle of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit from 1991 to 1992 and U.S. Supreme Court justices Byron White and Anthony Kennedy from 1993 to 1994. He is the first Supreme Court Justice to serve alongside a Justice for whom he once clerked (Kennedy).[11]

Early life and education

Gorsuch is the son of David Ronald Gorsuch (1937–2001)[12] and Anne Gorsuch Burford (née Anne Irene McGill; 1942–2004). A fourth-generation Coloradan,[13] Gorsuch was born in Denver, Colorado, and attended Christ the King, a K–8 Catholic school.[14] Both of Gorsuch's parents were lawyers, and his mother served in the Colorado House of Representatives from 1976 to 1980. In 1981, she was appointed by President Ronald Reagan to be the administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, becoming the first woman to hold that position.[15][16][14] At his mother's appointment, Gorsuch's family moved to Bethesda, Maryland. He attended Georgetown Preparatory School, a prestigious Jesuit prep school, where he was two years junior to Brett Kavanaugh, with whom he would later clerk at the Supreme Court and eventually serve with as a Supreme Court justice.[17][18][19] While attending Georgetown Prep, Gorsuch served as a United States Senate page in the early 1980s.[20] Gorsuch graduated from Georgetown Prep in 1985.

After high school, Gorsuch attended Columbia University and graduated cum laude in 1988 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science. While at Columbia, Gorsuch was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa.[15][21][22] He was also a member of Phi Gamma Delta fraternity.[23] As an undergraduate student, he wrote for the Columbia Daily Spectator student newspaper.[24][25] In 1986, he co-founded the alternative Columbia student newspaper The Fed.[26]

Gorsuch then attended Harvard Law School, where he was an editor on the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy.[15][21] He received a Harry S. Truman Scholarship to attend.[27][28] He was described as a committed conservative who supported the Gulf War and congressional term limits, on "a campus full of ardent liberals".[29] Former President Barack Obama was one of Gorsuch's classmates at Harvard Law.[30][31][32] Gorsuch graduated from Harvard Law in 1991 with a Juris Doctor cum laude.

In 2004 he was awarded a DPhil in law (legal philosophy) from the University of Oxford, where he completed research on assisted suicide and euthanasia as a postgraduate student of University College, Oxford.[5][15][21] A Marshall Scholarship enabled him to study at Oxford in 1992–93, where he was supervised by the natural law philosopher John Finnis of University College, Oxford.[33] His thesis was also supervised by Professor Timothy Endicott of Balliol College, Oxford.[5][6][8] In 1996, Gorsuch married his wife Louise, an English woman and champion equestrienne on Oxford's riding team whom he met during his stay at Oxford.[14][34]

Early legal career

Clerkships

Gorsuch served as a judicial clerk for Judge David B. Sentelle of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit from 1991 to 1992, and then for Supreme Court Justices Byron White and Anthony Kennedy from 1993 to 1994.[21][28][35] Gorsuch's work with White occurred right after White retired from the Supreme Court; therefore, Gorsuch assisted White with his work on the Tenth Circuit, where White sat by designation.[21] Gorsuch was part of a group of five law clerks assigned that year which included Brett Kavanaugh who described Gorsuch at the time stating: "He fit into the place very easily. He's just an easy guy to get along with. He doesn't have sharp elbows. We had a wide range of views, but we all really got along well."[36]

Private law practice

Instead of joining an established law firm, Gorsuch decided to join the two-year-old boutique firm Kellogg, Huber, Hansen, Todd, Evans & Figel (now Kellogg, Hansen, Todd, Figel & Frederick), where he focused on trial work.[14] After winning his first trial as lead attorney, a jury member told Gorsuch he was like Perry Mason.[14] He was an associate in the Washington, D.C., law firm from 1995 to 1997 and a partner from 1998 to 2005.[21][37] Gorsuch's clients included Colorado billionaire Philip Anschutz.[38] At Kellogg Huber, Gorsuch focused on commercial matters, including contracts, antitrust, RICO, and securities fraud.[21]

In 2002, Gorsuch penned an op-ed criticizing the Senate for delaying the nominations of Merrick Garland and John Roberts to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, writing that "the most impressive judicial nominees are grossly mistreated" by the Senate.[39]

In 2005, at Kellogg Huber, Gorsuch wrote a brief denouncing class action lawsuits by shareholders. In the case of Dura Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Broudo, Gorsuch opined that "The free ride to fast riches enjoyed by securities class action attorneys in recent years appeared to hit a speed bump" and that "the problem is that securities fraud litigation imposes an enormous toll on the economy, affecting virtually every public corporation in America at one time or another and costing businesses billions of dollars in settlements every year".[37]

U.S. Department of Justice

Gorsuch served as Principal Deputy to the Associate Attorney General, Robert McCallum, at the United States Department of Justice from 2005 until 2006.[21][28] As McCallum's principal deputy, Gorsuch assisted in managing the Department of Justice's civil litigation components, which included antitrust, civil, civil rights, environment, and tax divisions.[21]

While managing the United States Department of Justice Civil Division, Gorsuch was tasked with all the "terror litigation" arising from the president's War on Terror, successfully defending the extraordinary rendition of Khalid El-Masri, fighting the disclosure of Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse photographs, and, in November 2005, traveling to inspect the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.[40]

Gorsuch helped Attorney General Alberto Gonzales prepare for hearings after the public revelation of NSA warrantless surveillance (2001–07), and worked with Senator Lindsey Graham in drafting the provisions in the Detainee Treatment Act which attempted to strip federal courts of jurisdiction over the detainees.[41]

Judge on Tenth Circuit (2006–2017)

In January 2006, Philip Anschutz recommended Gorsuch's nomination to Colorado's U.S. senator Wayne Allard and White House Counsel Harriet Miers.[38] On May 10, 2006, Gorsuch was nominated by President George W. Bush to the seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit vacated by Judge David M. Ebel, who was taking senior status.[15] Like Gorsuch, Ebel was a former clerk of Supreme Court justice Byron R. White. The American Bar Association's Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary unanimously rated him "well qualified" in 2006.[21][42][43]

Just over two months later, on July 20, 2006, Gorsuch was confirmed by unanimous voice vote in the U.S. Senate.[44][45] Gorsuch was President Bush's fifth appointment to the Tenth Circuit.[46] When Gorsuch began his tenure at Denver's Byron White United States Courthouse, Justice Anthony Kennedy administered the oath of office.[39]

During his time on the Tenth Circuit, ten of Gorsuch's law clerks went on to become Supreme Court clerks, and he was sometimes regarded as a "feeder judge".[47] One of his former clerks, Jonathan Papik, became an associate justice of the Nebraska Supreme Court in 2018.[48]

Freedom of religion

Gorsuch advocates a broad definition of religious freedom that is inimical to Church–State separation advocates.[49][50][51]

In Hobby Lobby Stores v. Sebelius (2013), Gorsuch wrote a concurrence when the en banc circuit found the Affordable Care Act's contraceptive mandate on a private business violated the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.[52] That ruling was upheld 5–4 by the Supreme Court in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (2014).[53] When a panel of the court denied similar claims under the same act in Little Sisters of the Poor Home for the Aged v. Burwell (2015), Gorsuch joined Judges Harris Hartz, Paul Joseph Kelly Jr., Timothy Tymkovich, and Jerome Holmes in their dissent to the denial of rehearing en banc.[54] That ruling was vacated and remanded to the Tenth Circuit by the per curiam Supreme Court in Zubik v. Burwell (2016).[53]

In Pleasant Grove City v. Summum (2007), he joined Judge Michael W. McConnell's dissent from the denial of rehearing en banc, taking the view that the government's display of a donated Ten Commandments monument in a public park did not obligate the government to display other offered monuments.[55] Most of the dissent's view was subsequently adopted by the Supreme Court, which reversed the judgment of the Tenth Circuit.[53] Gorsuch has written that "the law [...] doesn't just apply to protect popular religious beliefs: it does perhaps its most important work in protecting unpopular religious beliefs, vindicating this nation's long-held aspiration to serve as a refuge of religious tolerance".[56]

Administrative law

Gorsuch has called for reconsideration of Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. (1984), in which the Supreme Court instructed courts to grant deference to federal agencies' interpretation of ambiguous laws and regulations. In Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Lynch (2016), Gorsuch wrote for a unanimous panel finding that court review was required before an executive agency could reject the circuit court's interpretation of an immigration law.[57][58]

Alone, Gorsuch added a concurring opinion, criticizing Chevron deference and National Cable & Telecommunications Ass'n v. Brand X Internet Services (2005) as an "abdication of judicial duty", writing that deference is "more than a little difficult to square with the Constitution of the framers' design".[59][60]

In United States v. Hinckley (2008), Gorsuch argued that one possible reading of the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act likely violates the nondelegation doctrine.[61] Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg had held the same view in their 2012 dissent of Reynolds v. United States.[62]

Interstate commerce

Gorsuch has been an opponent of the dormant Commerce Clause, which allows state laws to be declared unconstitutional if they too greatly burden interstate commerce. In 2011, Gorsuch joined a unanimous panel finding that the dormant Commerce Clause did not prevent the Oklahoma Water Resources Board from blocking water exports to Texas.[63] That ruling was affirmed by a unanimous Supreme Court in Tarrant Regional Water District v. Herrmann (2013).[64]

In 2013, Gorsuch joined a unanimous panel finding that federal courts could not hear a challenge to Colorado's internet sales tax.[65] That ruling was reversed by a unanimous Supreme Court in Direct Marketing Ass'n v. Brohl (2015).[64] In 2016, the Tenth Circuit panel rejected the challenger's dormant commerce clause claim, with Gorsuch writing a concurrence.[66]

In Energy and Environmental Legal Institute v. Joshua Epel (2015), Gorsuch held that Colorado's mandates for renewable energy did not violate the commerce clause by putting out-of-state coal companies at a disadvantage.[67] Gorsuch wrote that the Colorado renewable energy law "isn't a price-control statute, it doesn't link prices paid in Colorado with those paid out of state, and it does not discriminate against out-of-staters".[68][69]

Campaign finance

In Riddle v. Hickenlooper (2014), Gorsuch joined a unanimous panel of the Tenth Circuit in finding that it was unconstitutional for a Colorado law to set the limit on donations for write-in candidates at half the amount for major party candidates.[70] Gorsuch added a concurrence where he noted that although the standard of review of campaign finance in the United States is unclear, the Colorado law would fail even under intermediate scrutiny.[71]

Civil rights

In Planned Parenthood v. Gary Herbert (2016), Gorsuch wrote for the four dissenting judges when the Tenth Circuit denied a rehearing en banc of a divided panel opinion that had ordered the Utah governor to resume the organization's funding, which Herbert had blocked in response to a video controversy.[72][73]

In A.M., on behalf of her minor child, F.M. v. Ann Holmes (2016), the Tenth Circuit considered a case in which a 13-year-old child was arrested for burping and laughing in gym class. The child was handcuffed and arrested based on a New Mexico statute that makes it a misdemeanor to disrupt school activities. The child's family brought a federal 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (civil rights) action against school officials and the school resource officer who made the arrest, arguing that it was a false arrest that violated the child's constitutional rights. In a 94-page majority opinion, the Tenth Circuit held that the defendants enjoyed qualified immunity from suit.[74] Gorsuch wrote a four-page dissent, arguing that the New Mexico Court of Appeals had "long ago alerted law enforcement" that the statute that the officer relied upon for the child's arrest does not criminalize noises or diversions that merely disturb order in a classroom.[74][75][76]

Criminal law

In 2009, Gorsuch wrote for a unanimous panel finding that a court may still order criminals to pay restitution even after it missed a statutory deadline.[77] That ruling was affirmed 5–4 by the Supreme Court in Dolan v. United States (2010).[64]

In United States v. Games-Perez (2012), Gorsuch ruled on a case where a felon owned a gun in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(1), but alleged that he did not know that he was a felon at the time. Gorsuch joined the majority in upholding the conviction based on Tenth Circuit precedent. However, he filed a concurring opinion arguing that said precedent was wrongly decided: "The only statutory element separating innocent (even constitutionally protected) gun possession from criminal conduct in §§ 922(g) and 924(a) is a prior felony conviction. So the presumption that the government must prove mens rea here applies with full force."[78] In the 2019 case Rehaif v. United States, the Supreme Court overruled this decision with Gorsuch joining.

In 2013, Gorsuch joined a unanimous panel finding that intent does not need to be proven under a bank fraud statute.[79] That ruling was affirmed by a Supreme Court unanimous in judgment in Loughrin v. United States (2014).[64] In 2015, Gorsuch wrote a dissent to the denial of rehearing en banc when the Tenth Circuit found that a convicted sex offender had to register with Kansas after he moved to the Philippines.[80] The Tenth Circuit was then reversed by a unanimous Supreme Court in Nichols v. United States (2016).[64]

Death penalty

Gorsuch favors a strict reading of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA).[53] In 2015, he wrote for the court when it permitted Oklahoma attorney general Scott Pruitt to order the execution of Scott Eizember, prompting a thirty-page dissent by Judge Mary Beck Briscoe.[81][82] After the state's unsuccessful execution of Clayton Lockett, Gorsuch joined Briscoe when the court unanimously allowed Attorney General Pruitt to continue using the same lethal injection protocol. That ruling was upheld 5–4 by the Supreme Court in Glossip v. Gross (2015).[83]

List of judicial opinions

During his tenure on the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, Gorsuch authored 212 published opinions.[84] Some of those are the following opinions:

- United States v. Hinckley, 550 F. 3d 926 (2008) on principles of interpretation and construction of a statute, according to plain meaning and context

- United States v. Ford, 550 F. 3d 975 (2008) on entrapment and email evidence

- Blausey v. US Trustee, 552 F. 3d 1124 (2009) on procedure

- Williams v. Jones, 583 F. 3d 1254 (2009) dissent, on murder and evidence

- Wilson v. Workman, 577 F. 3d 1284 (2009) habeas corpus writ procedure

- Fisher v. City of Las Cruces, 584 F. 3d 888 (2009) Fourth Amendment excessive force claims against police officers

- Strickland v. United Parcel Service, Inc., 555 F. 3d 1224 (2009) on gender discrimination and harassment, arguing that if men are treated as equally badly as women, there is no claim

- American Atheists, Inc. v. Davenport, 637 F. 3d 1095 (2010) on crosses displayed on highways

- Flitton v. Primary Residential Mortgage, Inc. (2010) on jurisdiction over attorney fees in a gender discrimination and retaliation case

- Laborers' International Union, Local 578 v. NLRB, 594 F. 3d 732 (2010) dismissing the union's challenge to a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) finding that the union committed an unfair labor practice by persuading a company to dismiss a worker who did not pay union dues

- McClendon v. City of Albuquerque, 630 F. 3d 1288 (2011) dismissing class action lawsuit over inhumane jail conditions

- Public Service Co. of New Mexico v. NLRB, 692 F. 3d 1068 (2012) dismissing a union's claim that the NLRB was wrong to not find an unfair labor practice, when an employer dismissed a worker for deliberately disconnecting a customer's gas supply (no evidence that it treated this employee differently)

- United States v. Games-Perez, 695 F. 3d 1104 (2012) on imprisonment without trial

- United States v. Games-Perez, 667 F. 3d 1136 (2012) on criminal law procedure

- Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. v. Sebelius, 723 F. 3d 1114 (2013) on the Affordable Care Act and religious freedom

- Niemi v. Lasshofer, 728 F. 3d 1252 (2013) fugitive disentitlement doctrine

- Riddle v. Hickenlooper, 742 F. 3d 922 (2014) stating: "No one before us disputes that the act of contributing to political campaigns implicates a 'basic constitutional freedom,' one lying 'at the foundation of a free society' and enjoying a significant relationship to the right to speak and associate—both expressly protected First Amendment activities. Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 26 (1976)"

- Yellowbear v. Lampert, 741 F. 3d 48 (2014) freedom to practice religion in prison

- Teamsters Local Union No. 455 v. NLRB, 765 F. 3d 1198 (2014) denying a labor union's claim that a lockout entitled employees to back pay, under the NLRA 1935, 29 USC § 158(a)(1)

- United States v. Krueger, 809 F. 3d 1109 (2015) regarding the Fourth Amendment and search and seizures

- International Union of Operating Engineers v. NLRB Nos. 14-9605, 14-9613 (2015) on NLRB's review of an unfair labor practice by a union, removing an employee from an eligible work list and refusing her the right to review

- United States v. Arthurs (2016) evidence

- United States v. Mitchell (2016) evidence, tracking without a warrant

- NLRB v. Community Health Services, 812 F.3d 768 (2016) dissenting, arguing against an NLRB decision that interim earnings should not be disregarded when calculating back pay for employees whose hours were unlawfully reduced

- TransAm Trucking v. Administrative Review Board, 833 F. 3d 1206 (2016) dissenting against the majority's judgment that an employee was unjustly dismissed.

- Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Lynch, 834 F.3d 1142 (2016) on U.S. administrative law, doubting the doctrine of deference to the federal government by courts in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 US 837 (1984)

Nomination to Supreme Court

During the U.S. presidential election in September 2016, candidate Donald Trump included Gorsuch, as well as his circuit colleague Timothy Tymkovich, in a list of 21 current judges whom Trump would consider nominating to the Supreme Court if elected.[85][86] After Trump took office in January 2017, unnamed Trump advisers listed Gorsuch in a shorter list of eight of those names, who they said were the leading contenders to be nominated to fill the seat left vacant by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia.[87]

On January 31, 2017, President Trump announced his nomination of Gorsuch to the Supreme Court.[4] Gorsuch was 49 years old at the time of the nomination, making him the youngest nominee to the Supreme Court since the 1991 nomination of Clarence Thomas (who was 43).[88] It was reported by the Associated Press that, as a courtesy, Gorsuch's first call after the nomination was to President Obama's pick for the same position, Merrick Garland, Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Garland had been nominated by Obama on March 16, 2016. Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Chuck Grassley did not schedule a hearing for the nominee, leaving Garland's nomination to expire on January 3, 2017.[89] Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell invoked the so-called "Biden Rule" (of 1992) to justify the Senate's refusal to consider the nomination of Merrick Garland in a general election year.[90][91][92]

Trump formally transmitted his nomination to the Senate on February 1, 2017.[93] The American Bar Association unanimously gave Gorsuch its top rating—"Well Qualified"—to serve as Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.[94] His confirmation hearing before the Senate started on March 20, 2017.[95]

On April 3, the Senate Judiciary Committee approved his nomination with a party-line 11–9 vote.[96] On April 6, 2017, Democrats filibustered (prevented cloture) the confirmation vote of Gorsuch, after which the Republicans invoked the "nuclear option", allowing a filibuster of a Supreme Court nominee to be broken by a simple majority vote.[97]

On April 4, Buzzfeed and Politico ran articles highlighting similar language occurring in Gorsuch's book The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia and an earlier law review article by Abigail Lawlis Kuzma, Indiana's deputy attorney general. Academic experts contacted by Politico "differed in their assessment of what Gorsuch did, ranging from calling it a clear impropriety to mere sloppiness."[98][99][100][101]

John Finnis, who supervised Gorsuch's dissertation at Oxford, stated that "The allegation is entirely without foundation. The book is meticulous in its citation of primary sources. The allegation that the book is guilty of plagiarism because it does not cite secondary sources which draw on those same primary sources is, frankly, absurd." Kuzma stated, "I have reviewed both passages and do not see an issue here, even though the language is similar. These passages are factual, not analytical in nature, framing both the technical legal and medical circumstances of the 'Baby/Infant Doe' case that occurred in 1982."[99] In his book on Gorsuch, John Greenya described how Gorsuch was challenged during his confirmation hearings concerning some of his dissertation advisor's more strident views, which Gorsuch generally disagreed with.[102]

On April 7, 2017, the Senate confirmed Gorsuch's nomination to the Supreme Court by a 54–45 vote, with three Democrats (Heidi Heitkamp, Joe Manchin, and Joe Donnelly) joining all the Republicans in attendance.[103]

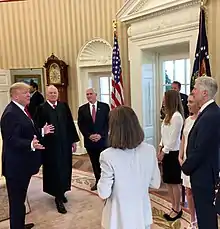

Gorsuch received his commission on April 8, 2017.[104] He was sworn into office on Monday, April 10, 2017, in two ceremonies. The chief justice of the United States administered the constitutional oath of office in a private ceremony at 9:00 a.m. at the Supreme Court, making Gorsuch the 101st associate justice of the Court. At 11:00 a.m., Justice Anthony M. Kennedy administered the judicial oath of office in a public ceremony at the White House Rose Garden.[105][106][107]

Tenure as Associate Justice (2017–present)

Banking regulation

Gorsuch wrote his first U.S. Supreme Court decision for a unanimous court in Henson v. Santander Consumer USA Inc., 582 U.S. ___ (2017). Gorsuch and the Court ruled against the borrowers, holding that Santander in this case is not a debt collector under the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act since they purchased the original defaulted car loans from CitiFinancial for pennies on the dollar, making Santander the owner of the debts and not merely an agent.[108] When the act was enacted, regulations were put on institutions that collected other companies' debts, but the act left unaddressed businesses collecting their own debts.[109][110]

Freedom of speech

Gorsuch joined the majority in National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v. Becerra, and Janus v. AFSCME, which both held unconstitutional certain forms of compelled speech.[111][112]

LGBT rights

In 2017, in Pavan v. Smith, the Supreme Court "summarily overruled" the Arkansas Supreme Court's decision to deny same-sex married parents the same right to appear on the birth certificate.[113] Gorsuch wrote a dissent, joined by Thomas and Alito, arguing that the Court should have fully heard the arguments of the case.[114]

In 2020, Gorsuch wrote the majority opinion in the combined cases of Bostock v. Clayton County, Altitude Express Inc. v. Zarda, and R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, ruling that businesses cannot discriminate in employment against LGBTQ people. Gorsuch argued that discrimination based on sexual orientation was illegal discrimination on the basis of sex, because the employer would be discriminating "for traits or actions it would not have questioned in members of a different sex".[115]

The ruling was 6–3 with Gorsuch being joined by Chief Justice Roberts and the court's four Democratic appointees.[116][117] Justices Thomas, Alito, and Kavanaugh dissented from the decision, arguing that it improperly extended the Civil Rights Act to include sexual orientation and gender identity.[118]

In October 2020, Gorsuch agreed with the justices in an "apparently unanimous" decision to deny an appeal from Kim Davis, a county clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples.[119]

Second Amendment

Gorsuch joined Justice Thomas's dissent from denial of certiorari in Peruta v. San Diego County, in which the Ninth Circuit had upheld California's restrictive concealed carry laws.[120]

Gorsuch dissented from the denial of an application for a stay presented to Chief Justice John Roberts in the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit case Guedes v. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (2019), a case challenging the Donald Trump administration's ban on bump stocks. Only Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas publicly dissented.[121]

Vagueness doctrine

In Sessions v. Dimaya, the Supreme Court ruled 5–4 to uphold the Ninth Circuit's decision that the residual clause in the Immigration and Nationality Act was unconstitutionally vague. Gorsuch joined Justices Kagan, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor in the opinion, as well as authoring a separate concurring opinion reiterating the importance of the vagueness doctrine within Justice Scalia's opinion in Johnson.[122]

Reproductive rights

In December 2018, Gorsuch dissented when the Court voted against hearing cases brought by the states of Louisiana and Kansas to deny Medicaid funding to Planned Parenthood.[123] Gorsuch, along with Justice Alito, joined the dissent authored by Justice Thomas, arguing that it was the court's job to hear the case.[124]

In February 2019, Gorsuch sided with three of the court's other conservative justices voting to reject a stay to temporarily block a law restricting abortion in Louisiana.[125] The law that the court temporarily stayed, in a 5–4 decision, would require that doctors performing abortions have admitting privileges in a hospital.[126] In June 2020, the Supreme Court struck down Louisiana's abortion restriction in June Medical Services, LLC v. Russo, a 5-4 decision; Gorsuch was among the four dissenting justices.[127][128]

Native American law

In March 2019, Justice Gorsuch departed from his four fellow conservative justices, joining the four more liberal Justices (in two plurality opinions) in a 5–4 majority in Washington State Dept. of Licensing v. Cougar Den, Inc.[129] The Court's decision sided with the Yakama Nation, striking down a Washington state tax on transporting gasoline, on the basis of an 1855 treaty in which the Yakama ceded a large portion of Washington in exchange for certain rights.[130] In his concurrence, which was joined by Justice Ginsburg, Gorsuch ended his opinion by writing: "Really, this case just tells an old and familiar story. The State of Washington includes millions of acres that the Yakamas ceded to the United States under significant pressure. In return, the government supplied a handful of modest promises. The state is now dissatisfied with the consequences of one of those promises. It is a new day, and now it wants more. But today and to its credit, the Court holds the parties to the terms of their deal. It is the least we can do."[131]

In May 2019, Gorsuch again joined the four more liberal justices in a decision favorable to the treaty rights of Native Americans, signing onto Justice Sotomayor's opinion to reach a 5-4 decision in Herrera v. Wyoming. This case held that hunting rights in Montana and Wyoming, granted by the U.S. government to the Native American Crow people by an 1868 treaty, were not extinguished by the 1890 grant of statehood to Wyoming.[132]

In July 2020, Gorsuch again joined the liberal justices to make a 5-4 majority in McGirt v. Oklahoma in a decision, written by Gorsuch, that found that "For Major Crimes Act purposes, land reserved for the Creek Nation since the 19th century remains 'Indian country.'"[133][134] In the majority case opinion, Gorsuch wrote, "Today we are asked whether the land these treaties promised remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law. Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word."[134]

President Trump's tax records

In July 2020, the Supreme Court ruled, in two separate 7-2 decisions in Trump v. Vance that the Manhattan district attorney could access President Trump's tax records, but returned the case of Congressional access to the lower courts, pending the outcome of that case.[135] Justice Gorsuch joined Roberts, Kavanaugh, and the four Democratic appointees in the majority in both cases while justices Thomas and Alito dissented from the decisions.[135][136]

Legal philosophy

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

|

Gorsuch is a proponent of originalism, the idea that the Constitution should be interpreted as perceived at the time of enactment, and of textualism, the idea that statutes should be interpreted literally, without considering the legislative history and underlying purpose of the law.[7][8][9] An editorial in the National Catholic Register opined that Gorsuch's judicial decisions lean more toward the natural law philosophy.[137]

In January 2019, Bonnie Kristian of The Week wrote that an "unexpected civil libertarian alliance" was developing between Gorsuch and Sonia Sotomayor "in defense of robust due process rights and skepticism of law enforcement overreach."[138]

Voting alignment

FiveThirtyEight used Lee Epstein et al.'s Judicial Common Space scores[139] (which are not based on a judge's behavior, but rather the ideology scores of either home state senators or the appointing president) to find a close alignment between the conservatism of other appellate and Supreme Court judges such as Brett Kavanaugh, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito.[140] The Washington Post's statistical analysis estimated that the ideologies of most of Trump's announced candidates were "statistically indistinguishable" and also associated Gorsuch with Kavanaugh and Alito.[141]

Judicial activism

In a 2016 speech at Case Western Reserve University, Gorsuch said that judges should strive to apply the law as it is, focusing backward, not forward, and looking to text, structure, and history to decide what a reasonable reader at the time of the events in question would have understood the law to be—not to decide cases based on their own moral convictions or the policy consequences they believe might serve society best.[142]

In a 2005 article published by National Review, Gorsuch argued that "American liberals have become addicted to the courtroom, relying on judges and lawyers rather than elected leaders and the ballot box, as the primary means of effecting their social agenda" and that they are "failing to reach out and persuade the public". Gorsuch wrote that, in doing so, American liberals are circumventing the democratic process on issues like gay marriage, school vouchers, and assisted suicide, and this has led to a compromised judiciary, which is no longer independent. Gorsuch wrote that American liberals' "overweening addiction" to using the courts for social debate is "bad for the nation and bad for the judiciary".[44][143]

States' rights and federalism

Gorsuch was described by Justin Marceau, a professor at the University of Denver's Sturm College of Law, as "a predictably socially conservative judge who tends to favor state power over federal power". Marceau added that the issue of states' rights is important since federal laws have been used to reel in "rogue" state laws in civil rights cases.[144]

Assisted suicide

In July 2006, Gorsuch's book, The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia, which was developed from his doctoral thesis, was published by Princeton University Press.[5][145][146][147]

In the book, Gorsuch makes clear his personal opposition to euthanasia and assisted suicide, arguing that the U.S. should "retain existing law [banning assisted suicide and euthanasia] on the basis that human life is fundamentally and inherently valuable, and that the intentional taking of human life by private persons is always wrong."[56][146][148]

Statutory interpretation

Gorsuch has been considered to follow in Scalia's footsteps as a textualist in statutory interpretation of the plain meaning of the law.[149][150] This was exemplified in his majority opinion for the landmark case Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia (590 U.S. ___ (2020)) which ruled that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 grants protection from employment discrimination due to sexual orientation and gender identity. Gorsuch wrote in the decision "An employer who fired an individual for being homosexual or transgender fires that person for traits or actions it would not have questioned in members of a different sex. Sex plays a necessary and undisguisable role in the decision, exactly what Title VII forbids."[151][152][153]

Professional associations and other appointments

Gorsuch has been active in several professional associations throughout his legal career.[21] Those associations have included the American Bar Association, the American Trial Lawyers Association, Phi Beta Kappa, the Republican National Lawyers Association, and the New York, Colorado, and District of Columbia Bar Associations.[21]

In May 2019 it was announced that Gorsuch would become the new chairman of the board of the National Constitution Center, succeeding former vice president Joe Biden.[154]

Personal life

Gorsuch and his wife, Marie Louise Gorsuch,[155] who is a British citizen, met at Oxford. They married at her Church of England parish church in Henley-on-Thames in 1996.[156] They live in Boulder, Colorado and have two daughters.[19][157][158]

Gorsuch has timeshare ownership of a cabin on the headwaters of the Colorado River outside Granby, Colorado with associates of Philip Anschutz.[38] He enjoys the outdoors and fly fishing and on at least one occasion went fly fishing with Justice Scalia.[13][159] He raises horses, chickens, and goats, and often arranges ski trips with colleagues and friends.[53]

He has authored two non-fiction books. His first book, The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia, was published by Princeton University Press in July 2006.[160] He is a co-author of The Law of Judicial Precedent, published by Thomson West in 2016.[37]

Religion

Justice Neil Gorsuch is the first member of a mainline Protestant denomination to sit on the Supreme Court since the retirement of John Paul Stevens in 2010.[161][162][163] He also has ties to Catholicism. Neil and his two siblings, brother J.J. and sister Stephanie, were raised Catholic and attended weekly Mass. Neil Gorsuch later attended Georgetown Preparatory School, a Catholic Jesuit school in North Bethesda, Maryland, from which he graduated in 1985.[14][17][18][19] Gorsuch's wife, Louise, is British-born; the two met while Neil was studying at Oxford. Louise was raised in the Church of England.[164] The two married at St. Nicholas' Anglican Church in Henley-on-Thames.[165]

When the couple returned to the United States they started attending Holy Comforter, an Episcopal parish in Vienna, Virginia, where he also volunteered as an usher.[163] Church records indicate that the Gorsuches were members of Holy Comforter. He later attended St. John's Episcopal Church in Boulder, Colorado, considered a liberal church because it kept an open-door policy for the LGBT community prior to legislation establishing gender preference equality laws.[4][166][167] The Episcopal Church and the Church of England are both members of the Anglican Communion, which considers itself to be both Catholic and Reformed but rejects papal authority.[168][169] After marrying in a non-Catholic ceremony and joining an Episcopal church, Gorsuch has not publicly stated if he considers himself a Catholic who is also a Protestant or simply a Protestant.[170]

Awards and honors

Gorsuch is the recipient of the Edward J. Randolph Award for outstanding service to the Department of Justice, and of the Harry S. Truman Foundation's Stevens Award for outstanding public service in the field of law.[158]

Bibliography

- Gorsuch, Neil (2019). A Republic, If You Can Keep It. New York: Crown Forum. ISBN 9780525576785.

- Gorsuch, Neil (September 5, 2019). "Disregarding the Separation of Powers Has Real-Life Consequences". National Review. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020.

- Gorsuch, Neil (2018). "In Tribute: Justice Anthony M. Kennedy" (PDF). Harvard Law Review. 132: 3–5.

- Gorsuch, Neil (September 3, 2016). Legacy of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia (video 59:59 mins). Tenth Circuit Court Bench & Bar Conference. Colorado Springs, Colorado: C-Span.

- Gorsuch, Neil (2016). "Access to Affordable Justice: A Challenge to the Bench, Bar, and Academy" (PDF). Judicature. 100 (3): 46–55.

- Gorsuch, Neil (2016). "Of Lions and Bears, Judges and Legislators, and the Legacy of Justice Scalia (2016 Sumner Canary Memorial Lecture)". Case Western Reserve Law Review. 66 (4): 905–920.

- Gorsuch, Neil (2014). "Law's Irony (Thirteenth Annual Barbara K. Olson Memorial Lecture)" (PDF). Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy. 37 (3): 743–756. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 30, 2017.

- Gorsuch, Neil; Coats, Nathan; Dunn, Stephanie; Myhre, Blain; Witt, Jesse (2013). "Effective Brief Writing". Appellate Practice Update 2013. OCLC 889590599.

- Gorsuch, Neil (2013). "Intention and the Allocation of Risk". In Keown, John; George, Robert (eds.). Reason, Morality, and Law. The Philosophy of John Finnis. pp. 413–424. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199675500.003.0026. ISBN 9780199675500.

- Gorsuch, Neil (2007). "A Reply to Raymond Tallis on the Legalization of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia". Journal of Legal Medicine. 28 (3): 327–332. doi:10.1080/01947640701554468. PMID 17885904. S2CID 36871391.

- Gorsuch, Neil (May 18, 2007). "The assisted suicide debate". The Times Literary Supplement.

- Gorsuch, Neil (2006). The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400830343. ISBN 978-1-4008-3034-3.

- Gorsuch, Neil; Matey, Matey (2005). "Settlements in Securities Fraud Class Actions: Improving Investor Protections" (PDF). Critical Legal Issues Working Paper Series. 128.

- Gorsuch, Neil (February 7, 2005). "Liberals'N'Lawsuits". National Review Online. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020.

- Gorsuch, Neil; Matey, Paul (January 31, 2005). "No Loss, No Gain". Legal Times.

- Gorsuch, Neil; Wood, Diane; Yahner, Ann; Issacharoff, Samuel; Anderson, Brian; Bryant, Arthur (September 13, 2004). Panel 2: Tools for Ensuring that Settlements Are "Fair, Reasonable, and Adequate" (PDF). Protecting Consumer Interests in Class Actions. pp. 84–139. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2020. Transcript published by The Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 18: 1197.

- Gorsuch, Neil (March 18, 2004). "Letter to the Editor: Nonpartisan Fee Awards". The Washington Post. p. A30. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020.

- Gorsuch, Neil (2004). "The Legalization of Assisted Suicide and the Law of Unintended Consequences: A Review of the Dutch and Oregon Experiments and Leading Utilitarian Arguments for Legal Change". Wisconsin Law Review. 2004: 1347–2424.

- Gorsuch, Neil (2004). The right to receive assistance in suicide and euthanasia, with particular reference to the law of the United States (DPhil thesis). University of Oxford.

- Gorsuch, Neil (May 4, 2002). "Justice White and judicial excellence". United Press International. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020.

- Gorsuch, Neil (2000). "The Right to Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia" (PDF). Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy. 23 (2): 599–710. PMID 12524693.

- Gorsuch, Neil (November 4, 1992). "Rule of Law: The Constitutional Case for Term Limits". The Wal Street Journal. p. A15.

- Gorsuch, Neil; Guzman, Michael (1991). "Will the Gentlemen Please Yield? A Defense of the Constitutionality of State-Imposed Term Limitations". Hofstra Law Review. 20: 341–385. Also published as: Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 178 (1992).

References

- "How to pronounce Gorsuch". The Washington Post. March 22, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- "Senate Confirms Gorsuch as Supreme Court Justice". The New York Times. April 7, 2017.

- "News Wrap: Alabama governor resigning over ethics charges". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- Barnes, Robert (January 31, 2017). "Trump picks Colo. appeals court judge Neil Gorsuch for Supreme Court". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- Gorsuch, Neil McGill (2004). The right to receive assistance in suicide and euthanasia, with particular reference to the law of the United States. ora.ox.ac.uk (DPhil thesis). University of Oxford. OCLC 59196002. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.401384.

- "Judge Neil M. Gorsuch". Administrative Office of the United States Courts. The United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- Totenberg, Nina (January 24, 2017). "3 Judges Trump May Nominate For The Supreme Court". NPR.

- Karl, Jonathan (January 24, 2017). "Judge Neil Gorsuch Emerges as Leading Contender for Supreme Court". ABC News.

- Ponnuru, Ronesh (January 31, 2017). "Neil Gorsuch: A Worthy Heir to Scalia". National Review.

- Kelleher, J. Paul (March 20, 2017). "Neil Gorsuch's "natural law" philosophy is a long way from Justice Scalia's originalism". Vox. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- Livni, Ephrat (April 7, 2017). "Neil Gorsuch is the first US Supreme Court justice to sit on the bench with his high-court boss". Quartz. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- "David Ronald Gorsuch". geni.com.

- de Vogue, Ariane (February 1, 2017). "Meet Neil Gorsuch: A fly-fishing Scalia fan". CNN.

- Kindy, Kimberly; Horwitz, Sari; Wan, William (February 19, 2017). "Simply stated, Gorsuch is steadfast and surprising". The Washington Post. p. A1. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- "Hon. Neil Gorsuch". The Federalist Society. Archived from the original on January 25, 2017.

- Savage, David G. (January 24, 2017). "Conservative Colorado judge emerges as a top contender to fill Scalia's Supreme Court seat". Los Angeles Times.

- Neil Gorsuch - Religion, Denverpost.com, February 10, 2017; accessed February 25, 2017.

- "Notable Alumni". Georgetown Preparatory School. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- Aguilera, Elizabeth (November 20, 2006). "10th Circuit judge's oath a family affair". The Denver Post.

- Congress (July 20, 2006). Senator Mark Udall in support of Neil M. Gorsuch for Tenth Circuit Judge. Congressional Record--Senate. 152. p. 15384. ISBN 9780160861550. Retrieved June 12, 2017 – via Google Books.

- Congress (July 20, 2006). Neil M. Gorsuch. Congressional Record—Senate. 152. p. 15346. ISBN 9780160861550. Retrieved June 12, 2017 – via Google Books.

- Clarke, Sara (January 31, 2017). "10 Things You Didn't Know About Neil Gorsuch". US News and World Report. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- Fertoli, Annemarie (February 1, 2017). "Columbia Classmates Recall Judge Neil Gorsuch's Time in New York". WNYC.

- "Columbia Daily Spectator". spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu. October 1, 1985.

- "Columbia Daily Spectator". spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu. October 1, 1985.

- Marhoefer, Laurie (December 1, 1999). "The History of Columbia's Oldest Student Paper". The Fed.

- "Joseph E. Stevens Award | The Harry S. Truman Scholarship Foundation". Truman.gov. Archived from the original on December 13, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- Neil M. Gorsuch '91 nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court, Harvard Law Today, January 31, 2017.

- Levenson, Michael (February 2, 2017). "At Harvard Law, Gorsuch stood out on a campus full of liberals". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- Gerstein, Josh (January 31, 2017). "Neil Gorsuch is Trump's SCOTUS nominee". Politico. Washington, DC. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- "Supreme Court Neil Gorsuch: Who is Trump's nominee?". BBC. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- Clauss, Kyle Scott (February 1, 2017). "Neil Gorsuch, Trump's Supreme Court Pick, Attended Harvard Law with Obama". Boston. Boston, Massachusetts. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- Warren, Ashley. "Judge Neil M. Gorsuch ('92) sworn in to US Supreme Court – Association of Marshall Scholars". www.marshallscholars.org. Association of Marshall Scholars. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- Rayner, Gordon (February 1, 2017). "British family of Donald Trump Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch 'thrilled but terrified'". The Telegraph. The Daily Telegraph.

- The same 1993 Term, Gorsuch's Harvard Law School classmates David T. Goldberg (HLS 1991) and Julius Genachowski (HLS 1991) both clerked for Justice David Souter.

- Greenya, John (2018). Gorsuch: The Judge Who Speaks for Himself. Threshold Editions. Page 55.

- Mauro, Tony (January 24, 2017). "Three Things to Know About Neil Gorsuch, SCOTUS Front-Runner". The National Law Journal. (subscription required)

- Charlie Savage; Julie Turkewitz (March 15, 2017). "Neil Gorsuch Has Web of Ties to Secretive Billionaire". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Liptak, Adam (February 1, 2017). "In Judge Neil Gorsuch, an Echo of Scalia in Philosophy and Style". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- Charlie Savage (March 16, 2017). "Neil Gorsuch Helped Defend Disputed Bush-Era Terror Policies". The New York Times. p. A13. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Charlie Savage (March 19, 2017). "Newly Public Emails Hint at Gorsuch's View of Presidential Power". The New York Times. pp. A15. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Johnson, Carrie. Who Is Neil Gorsuch, Trump's First Pick For The Supreme Court?, NPR, February 5, 2017.

- Ratings of Article III Judicial Nominees: 109th Congress, American Bar Association Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary (last updated January 10, 2008).

- Mulkern, Anne C. (July 20, 2006). "Gorsuch confirmed for 10th Circuit". The Denver Post.

- Pres. Nom. 1565, 109th Cong. (2006).

- Rutkus, Denis Steven; Scott, Kevin M.; Bearden, Maureen (January 23, 2007), U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominations by President George W. Bush During the 107th–109th Congresses (PDF), Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress, p. 63, retrieved February 11, 2017

- "Supreme Court Clerk Hiring Watch: An Analysis Of The October Term 2016 Clerk Class". Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Pilger, Lori. "Ricketts' pick for Nebraska Supreme Court 'operating on higher level,' colleague says". journalstar.com. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- Boston, Rob (December 29, 2017). "Here Are the Top Ten Church–State Stories from 2017". Americans United for Separation of Church and State. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- Mystal, Elie (April 10, 2017). "Religious Freedom or Religious Preference? Neil Gorsuch Will Decide Next Week". Above the Law. New York. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- Epps, Garrett (March 20, 2017). "Gorsuch's Selective View of 'Religious Freedom'". The Atlantic. Washington, DC. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- "Recent Cases: Tenth Circuit Holds For-Profit Corporate Plaintiffs Likely to Succeed on the Merits of Substantial Burden on Religious Claim", 127 Harv. L. Rev. 1025 (2014) discussing Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. v. Sebelius, 723 F.3d 1114 (10th Cir. 2013).

- Citron, Eric, Potential nominee profile: Neil Gorsuch, SCOTUSblog.com, January 13, 2017.

- Little Sisters of the Poor Home for the Aged v. Burwell, 799 F.3d 1315 (10th Cir. 2015) (Hartz, J., dissenting from denial of rehearing en banc).

- Summum v. Pleasant Grove City, 499 F.3d 1170, 1175 (10th Cir. 2007) (McConnell, J., dissenting from denial of rehearing en banc)..

- Barnes, Robert (January 28, 2017). "Neil Gorsuch naturally equipped for his spot on Trump's Supreme Court shortlist". Washington Post. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- Frankel, Allison (August 24, 2016). "Is court deference to federal agencies unconstitutional? 10th Circuit judge thinks so". Reuters. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Lynch, 834 F.3d 1142 (10th Cir. 2016).

- Adler, Jonathan H. (August 24, 2016). "Should Chevron be reconsidered? A federal judge thinks so". The Washington Post.

- "Hugo Rosario Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Loretta E. Lynch" (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. August 23, 2016.

- "United States of America v. Shawn Lloyd Hinckley" (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. December 9, 2008.

- "Reynolds v. United States". SCOTUSBlog.com. January 23, 2012.

- Tarrant Regional Water Dist. v. Herrmann, 656 F.3d 1222 (10th Cir. 2011).

- Recht, Hannah (January 2, 2017). "Seven Cases Where the Supreme Court Sided With Neil Gorsuch (And One Time it Didn't)". Bloomberg News. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- Direct Marketing Ass'n v. Brohl, 735 F. 3d 904 (10th Circ. 2013).

- Direct Marketing Ass'n v. Brohl, 814 F.3d 1129 (10th Cir. 2016).

- Energy and Environment Legal Institute v. Epel, 793 F.3d 1169 (10th Cir. 2015).

- Proctor, Cathy (July 14, 2015). "Federal judges rule on Colorado's renewable energy mandate". Denver Business Journal.

- "Energy and Environmental Legal Institute v. Joshua Epel" (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. July 13, 2015.

- Torres-Spelliscy, Ciara (February 3, 2017). "Neil Gorsuch Understands Campaign Finance — And That's The Problem". Brennan Center for Justice. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Riddle v. Hickenlooper, 742 F.3d 922 (10th Cir. 2014).

- Robert Barnes (March 18, 2017). "Rulings offer glimpse into what kind of justice Gorsuch would be". The Washington Post. p. A1. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Planned Parenthood Association of Utah v. Herbert, 839 F.3d 1301 (10th Cir. 2016).

- "A.M., on behalf of her minor child, F.M. v. Ann Holmes; Principal Susan Labarge; Arthur Acosta, City of Albuquerque Police Officer, in his individual capacity" (PDF). United States Court of Appeals Tenth Circuit. July 25, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2017. Majority finding on qualified immunity, pp. 93-94; Gorsuch dissent, pp. 1-4.

- Feldman, Noah (July 27, 2016). "A Belch in Gym Class. Then Handcuffs and a Lawsuit". Bloomberg. New York. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- Sandlin, Scott (July 28, 2016). "Burp arrest of 7th-grader upheld by fed appeals court". Albuquerque Journal. Albuquerque, New Mexico.

- United States v. Dolan, 571 F.3d 1022 (10th Cir. 2009).

- "United States of America v. Miguel Games-Perez" (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. September 17, 2012.

- United States v. Loughrin, 710 F.3d 1111 (10th Cir. 2013)

- United States v. Nichols, 784 F. 3d 666, 667 (10th 2015) (Gorsuch, J., dissenting from denial of rehearing en banc).

- Boczkiewicz, Robert (September 15, 2015). "Court upholds death penalty in deadly 2003 Oklahoma crime spree". The Oklahoman.

- Eizember v. Trammell, 803 F.3d 1129 (10th Cir. 2015).

- "The Supreme Court, 2014 Term: Leading Cases" (PDF). Harvard Law Review. 129: 171. 2015.

- "Selected Resources on Neil M. Gorsuch". Law Library of Congress. Library of Congress. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- Carpentier, Megan (September 24, 2016). "Trump's supreme court picks: from Tea Party senator to anti-abortion crusader". The Guardian. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- "Donald Trump Supreme Court List". Donaldjtrump/com. Archived from the original on May 2, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- Gerstein, Josh (January 3, 2017). "A closer look at Trump's potential Supreme Court nominees". Politico.

- Davis, Julie Hirschfeld; Landler, Mark (February 1, 2017). "Trump's Court Pick Sets Up Political Clash—Democrats Digging In—Gorsuch Would Restore a 5-to-4 Split". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- "Gorsuch Phoned Garland, the Judge GOP Rejected", Telegram.com, February 1, 2017.

- "In Context: The 'Biden Rule' on Supreme Court nominations in an election year". PolitiFact. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- Davis, Julie Hirschfeld (February 22, 2016). "Joe Biden Argued for Delaying Supreme Court Picks in 1992 - The New York Times". The New York Times. Nytimes.com. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- DeBonis, Mike (February 22, 2016). "Joe Biden in 1992: No nominations to the Supreme Court in an election year". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- "Congressional Record". Congress.gov. February 1, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- "ABA Committee on Federal Judiciary Rates Supreme Court Nominee Neil Gorsuch "Well Qualified"". americanbar.org. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- Kim, Seung Min. "Gorsuch confirmation hearing set for March 20". Politico. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- Flegenheimer, Matt (April 4, 2017). "Democrats' Vow to Bar Gorsuch Sets Up a Clash, Senate Decorum Fades, Seeing 'No Alternative,' Republicans Plan to Bypass Filibuster". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- Killough, Ashley. "GOP triggers nuclear option on Neil Gorsuch nomination". CNN Politics. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- "Analysis | Neil Gorsuch's 11th-hour plagiarism scare". The Washington Post.

- Bryan Logan (April 4, 2016) Neil Gorsuch is accused of plagiarism amid a heated Supreme Court confirmation fight, businessinsider.com; accessed April 15, 2017.

- "Gorsuch's writings borrow from other authors". Politico. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- "A Short Section In Neil Gorsuch's 2006 Book Appears To Be Copied From A Law Review Article". BuzzFeed.

- Greenya, John (2018). Gorsuch: The Judge Who Speaks for Himself. Threshold Editions. Page 47.

- Adam Liptak; Matt Flegenheimer (April 8, 2017). "Neil Gorsuch Confirmed by Senate as Supreme Court Justice". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- "Gorsuch, Neil M. - Federal Judicial Center". fjc.gov. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- Totenberg, Nina (April 7, 2017). "Senate Confirms Gorsuch To Supreme Court". NPR. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- "President Donald J. Trump Congratulates Judge Neil M. Gorsuch on his Historic Confirmation". April 7, 2017.

- "Gorsuch sworn in as Supreme Court justice in Rose Garden as Trump beams". Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- Henson v. Santander Consumer USA Inc., U.S. Supreme Court, June 12, 2017.

- Liptak, Adam (June 12, 2017). "Supreme Court Bars Favoring Mothers Over Fathers in Citizenship Case". The New York Times.

- Williams, Joseph P. Neil Gorsuch Submits First Legal Opinion as a Supreme Court Judge, U.S. News & World Report, June 12, 2017.

- "NIFLA v. Becerra" (PDF).

- "Janus v. AFSCME" (PDF).

- Liptak, Adam (June 26, 2017). "Gay Couples Entitled to Equal Treatment on Birth Certificates, Justices Rule". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Barnes, Robert (July 16, 2017). "A Supreme Court mystery: Has Roberts embraced same-sex marriage ruling?". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- "Justices rule LGBT people protected from job discrimination". AP NEWS. June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Reporter, Ariane de Vogue, CNN Supreme Court. "Why Trump's Supreme Court appointee Neil Gorsuch just protected LGBTQ rights". CNN. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Kendall, Jess Bravin and Brent (June 15, 2020). "Supreme Court Rules for Gay and Transgender Rights in the Workplace". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- "Supreme Court extends employment protections to LGBT individuals". Roll Call. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- "Supreme Court rejects appeal from county clerk who wouldn't issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples". NBC News. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Peruta v. California" (PDF).

- Liptak, Adam (April 17, 2018). "Justice Gorsuch Joins Supreme Court's Liberals to Strike Down Deportation Law". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- Higgins, Tucker (December 10, 2018). "Supreme Court hamstrings states' efforts to defund Planned Parenthood". www.cnbc.com. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- "US Supreme Court Justices won't hear states' appeal over Planned Parenthood". FOX6Now.com. December 10, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- "Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts joins liberal justices to block Louisiana abortion clinic law". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Supreme Court Stops Louisiana Abortion Law From Being Implemented". NPR.org. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Supreme Court strikes, in 5-4 ruling, down restrictive Louisiana abortion law". NBC News. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- "Supreme Court Hands Abortion-Rights Advocates A Victory In Louisiana Case". NPR.org. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- Martin, Nick (March 20, 2019). "Gorsuch Sides With Liberal Justices to Spoil Washington's Attempt to Rewrite Tribal Law". Splinter. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- Deshais, Nicholas (March 21, 2019). "Neil Gorsuch joins liberals giving Yakama Nation a Supreme Court victory over state of Washington | The Spokesman-Review". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- "Washington State Dept. of Licensing v. Cougar Den, Inc, No. 16-1498 | Casetext". casetext.com. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- Ablavsky, Gregory (May 20, 2019). "Opinion analysis: Court rejects issue preclusion in affirming Crow Tribe's treaty hunting right". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- Higgins, Tucker; Mangan, Dan (July 9, 2020). "Supreme Court says eastern half of Oklahoma is Native American land". CNBC. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- Liptak, Adam; Healy, Jack (July 9, 2020). "Supreme Court Rules Nearly Half of Oklahoma Is Indian Reservation". The New York Times. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- Liptak, Adam (July 9, 2020). "Supreme Court Rules Trump Cannot Block Release of Financial Records". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- "Supreme Court rules Manhattan prosecutor can access Trump financial records". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- Kengor, Paul. "Neil Gorsuch and Natural Law". Ncregister.com. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- Kristian, Bonnie (January 16, 2019). "The unexpected alliance of Sonia Sotomayor and Neil Gorsuch". The Week. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- Epstein, Lee; Martin, Andrew D.; Segal, Jeffrey A.; Westerland, Chad (May 2007). "The Judicial Common Space". Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization. 23 (2): 303–325. doi:10.1093/jleo/ewm024. hdl:10.1093/jleo/ewm024.

- Roeder, Oliver (July 6, 2018). "How Four Potential Nominees Would Change The Supreme Court". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- Cope, Kevin (July 7, 2018). "Exactly how conservative are the judges on Trump's short list for the Supreme Court? Take a look at this one chart". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- de Vogue, Ariane (January 25, 2017). "How Neil Gorsuch could end up as Donald Trump's Supreme Court nominee". CNN.

- Gorsuch, Neil (February 7, 2005). "Liberals 'N' Lawsuits". National Review.

- Simpson, Kevin (December 11, 2016). "Neil Gorsuch: Elite credentials, conservative western roots land Denver native on SCOTUS list". The Denver Post.

- Gerald Dworkin (March 20, 2017). "The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia (review)". The New Rambler. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Gorsuch, N.M. (2009). The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia. New Forum Books. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3034-3. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- Laughland, Oliver; Redden, Molly; Booth, Robert; Bowcott, Owen (February 3, 2017). "Oxford scholar who was mentor to Neil Gorsuch compared gay sex to bestiality". The Guardian. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- Matthew, Dylan (February 5, 2017). "I read Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch's book. It's very revealing". Vox.com. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- Chemerinsky, Erwin (August 1, 2019). "Chemerinsky: Justice Gorsuch fulfills expectations from the right and the left". ABA Journal. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Barnes, Robert; Min Kim, Sueng (September 6, 2019). "'Everything conservatives hoped for and liberals feared': Neil Gorsuch makes his mark at the Supreme Court". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Williams, Pete (June 15, 2020). "Supreme Court rules existing civil rights law protects gay and lesbian workers". NBC News. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- de Vogue, Ariana (June 15, 2020). "Why Trump's Supreme Court appointee Neil Gorsuch just protected LGBTQ rights". CNN. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Stern, Mark Joseph (June 15, 2020). "Neil Gorsuch Just Handed Down a Historic Victory for LGBTQ Rights". Slate. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Sherman, Mark (May 14, 2019). "Gorsuch replaces Biden as chair of civic education group". AP NEWS.

- Dube Dwilson, Stephanie (January 31, 2017). "Neil Gorsuch's Family: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know". Heavy.

- "Neil Gorsuch's wife, Louise: The outdoorsy, religious Brit who captured his heart". April 20, 2017.

- Burness, Alex. Students of Supreme Court candidate Neil Gorsuch at CU law school cite fairness, dedication to truth, Denver Post, February 1, 2017.

- "University of Colorado Law School website: Judge Neil Gorsuch page". University of Colorado. Boulder, Colorado. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

Judge Neil M. Gorsuch was nominated to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit in May 2006. His nomination was confirmed in the United States Senate by unanimous voice vote.

- "Supreme Court choice Neil Gorsuch draws Democrat opposition". BBC. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- Taylor, Audrey; Sands, Geneva (January 26, 2017). "Judge Neil Gorsuch: What You Need to Know About the Possible SCOTUS Nominee". ABC News.

- "Neil Gorsuch belongs to a notably liberal church — and would be the first Protestant on the Court in years". Washington Post. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Petiprin, Andrew. "Guest opinion column: Episcopal Church a fitting place for conservative Neil Gorsuch". OrlandoSentinel.com. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- "What Neil Gorsuch's faith and writings could say about his approach to religion on the Supreme Court". The Denver Post. February 10, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Burke, Daniel. "What is Neil Gorsuch's religion? It's complicated". CNN. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- "Neil Gorsuch's wife, Louise: The outdoorsy, religious Brit who captured his heart". Fox News. April 20, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- "Neil Gorsuch Belongs to a Notably Liberal Church—and Would Be the First Protestant on the Court in Years". The Washington Post. February 1, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- Shellnutt, Kate. "Trump's Supreme Court Pick: Religious Freedom Defender Neil Gorsuch". Christianity Today. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- "What is the difference between the Episcopal Church and the Roman Catholic Church?". Episcopal Church. March 18, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- "Protestant and Catholic". Church of Ireland. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- Burke, Daniel. "What is Neil Gorsuch's religion? It's complicated". CNN Religion. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

Further reading

- Questionnaire for the Nominee to the Supreme Court submitted to the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary

- Congressional Research Service Report R44778, Judge Neil M. Gorsuch: His Jurisprudence and Potential Impact on the Supreme Court, coordinated by Andrew Nolan, Caitlin Devereaux Lewis, and Kate M. Manuel (2017).

- Congressional Research Service Report R44772, Majority, Concurring, and Dissenting Opinions by Judge Neil M. Gorsuch, coordinated by Michael John Garcia (2017).

- Congressional Research Service Legal Sidebar, The Essential Neil Gorsuch Reader: What Judge Gorsuch Cases Should You Read? (2017).

Videos

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Law's Irony lecture as given at the Federalist Society (video 29 min.) YouTube.

External links

- Neil Gorsuch at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Neil Gorsuch at Ballotpedia

- Selected Resources on Neil M. Gorsuch, Law Library of Congress website

- Nominee Spotlight on Judge Neil M. Gorsuch at the Stanford Law Review Online

- Biography, whitehouse.gov

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by – |

Principal Deputy Associate Attorney General 2005–2006 |

Succeeded by – |

| Preceded by David M. Ebel |

Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit 2006–2017 |

Succeeded by Allison H. Eid |

| Preceded by Antonin Scalia |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 2017–present |

Incumbent |

| U.S. order of precedence (ceremonial) | ||

| Preceded by Elena Kagan as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court |

Order of Precedence of the United States as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court |

Succeeded by Brett Kavanaugh as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court |