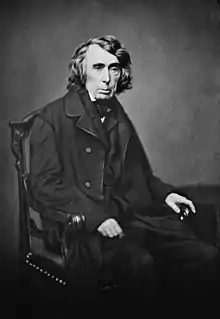

Samuel Freeman Miller

Samuel Freeman Miller (April 5, 1816 – October 13, 1890) was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court who served from 1862 to 1890. He was a physician and lawyer.

Samuel Freeman Miller | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office July 16, 1862 – October 13, 1890 | |

| Nominated by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Peter Daniel |

| Succeeded by | Henry Brown |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 5, 1816 Richmond, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | October 13, 1890 (aged 74) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (Before 1854) Republican (1854–1890) |

| Education | Transylvania University (MD) |

Early life, education, and medical career

Born in Richmond, Kentucky, Miller was the son of yeoman farmer Frederick Miller and his wife Patsy. He earned a medical degree in 1838 from Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky. While practicing medicine for a decade in Barbourville, Kentucky,[1] he studied the law on his own and was admitted to the bar in 1847. Favoring the abolition of slavery, which was prevalent in Kentucky, he supported the Whigs in Kentucky.

Career

In 1850, Miller moved to Keokuk, Iowa, which was a state more amenable to his views on slavery, and he immediately freed his few slaves who had come with his family from Kentucky. Active in Iowa politics, he supported Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Lincoln nominated Miller to the Supreme Court on July 16, 1862, after the beginning of the American Civil War. His reputation was so high that Miller was confirmed half an hour after the Senate received notice of his nomination.

His opinions strongly favored Lincoln's positions, and he upheld his wartime suspension of habeas corpus and trials by military commission. After the war, his narrow reading of the Fourteenth Amendment—he wrote the opinion in the Slaughterhouse Cases—limited the effectiveness of the amendment. Miller wrote the majority opinion in Bradwell v. Illinois, which held that the right to practice law was not constitutionally protected under the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

He later joined the majority opinions in United States v. Cruikshank and the Civil Rights Cases, holding that the amendment did not give the U.S. government the power to stop private—as opposed to state-sponsored—discrimination against blacks. In Ex Parte Yarbrough, 110 U.S. 651 (1884), however, Miller held that the federal government had broad authority to act to protect black voters from violence by the Ku Klux Klan and other private groups. Miller also supported the use of broad federal power under the Commerce Clause to override state regulations, as in Wabash v. Illinois.

Justice Miller wrote 616 opinions in his 28 years on the Court; Justice Field (whose 34 year SCOTUS tenure mostly overlapped Miller's) wrote 544 opinions; Chief Justice Marshall wrote 508 opinions in his 33 years on the Court.</ref> leading future Chief Justice William Rehnquist to describe him as "very likely the dominant figure" on the Court in his time.[2] When Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase died in 1873, attorneys and law journals across the country lobbied for Miller to be appointed to succeed him, but President Ulysses Grant was determined to appoint an outsider; he ultimately chose Morrison Waite. In his tribute to Miller delivered in Portland, Oregon, on October 16, 1890, George Henry Williams stated his support of Miller in detailing his interactions with President Ulysses S. Grant about Chase's replacement.[3]

After the 1876 presidential election between Rutherford Hayes and Samuel Tilden, Miller served on the electoral commission that awarded the disputed electoral votes to the Republican Hayes. In the 1880s, his name was floated as a Republican candidate for president.

In the winter of 1889 and spring of 1890, Justice Miller delivered a series of ten lectures on constitutional law at the National University School of Law in Washington D.C. They were published posthumously, along with two earlier lectures delivered in 1887.[4]

Personal

Miller, a religious liberal, belonged to the Unitarian Church and served as President of the Unitarians' National Conference. He died in Washington, D.C., while still a member of the Court. Following his death in 1890, his funeral was held at Keokuk's First Unitarian Church;[5] Miller had been one of the congregation's founders.[6] He is buried at Oakland Cemetery in Keokuk, Iowa.

Miller's first wife was Lucy Love Ballinger Miller (1827 – 1854) whom he married in 1842, and with whom he had three daughters. In 1856, he married Eliza Winter Reeves (1827 – 1900), with whom he had a son and daughter.[6] The second of his five children, Patty Miller Stocking, as an adult wrote and published letters on European travel.

List of most notable opinions

- Watson v. Jones, 80 U.S. 679 (1871)

- The Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873)

- Murdock v. Memphis, 87 U.S. 20 Wall. 590 590 (1874)

- United States v. Kagama, 118 U.S. 375 (1886)

- In re Neagle, 135 U.S. 1 (1890)

- In re Burrus, 136 U.S. 586 (1890)

See also

- Justice Samuel Freeman Miller House, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in Iowa

- List of Justices of the United States Supreme Court

References

- Ulm, Aaron Hardy (August 15, 1957). "Samuel Freeman Miller, M.D". New England Journal of Medicine. 257 (7): 327–329. doi:10.1056/NEJM195708152570709.

- Rehnquist, William, Centennial Crisis: the Disputed Election of 1876, pg. 155

- Williams, George H. (1895). Occasional Addresses. Portland, Oregon: F.W. Baltes and Company. pp. 72-76.

- Miller, Samuel. Lectures on the Constitution of the United States (Bank and Brothers, 1891).

- Iutzi, Cindy. "Keokuk Church on Endangered List, Daily Gate City, 2014-04-25. Accessed 2015-08-06.

- Ross, Michael. Justice of Shattered Dreams: Samuel Freeman Miller and the Supreme Court During the Civil War Era, pp. 20-21 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003).

Further reading

- Ross, Michael A.(1997), "Hill Country Doctor: The Early Life and Career of Supreme Court Justice Samuel F. Miller in Kentucky, 1816-1849," The Filson History Quarterly, Vol. 71 (October): 430–446.

- Ross, Michael A. (2003). Justice of Shattered Dreams: Samuel Freeman Miller and the Supreme Court during the Civil War Era. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2924-0.

- ——— (1998). "Justice Miller's Reconstruction: The Slaughter-House Cases, Health Codes, and Civil Rights in New Orleans, 1861-1873". Journal of Southern History. 64 (4): 649–676. doi:10.2307/2587513. JSTOR 2587513.

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Peter Daniel |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1862–1890 |

Succeeded by Henry Brown |