Beryl May Dent

Beryl May Dent MIEE (10 May 1900 – 9 August 1977) was a British mathematical physicist, technical librarian, and a programmer of early analogue and digital computers to solve electrical engineering problems. She was born in Chippenham, Wiltshire, the eldest daughter of schoolteachers. The family left Chippenham in 1901, after her father became head teacher of the then recently established Warminster County School. She graduated from the University of Bristol in 1923 with First Class Honours in applied mathematics. She was awarded the Ashworth Hallett scholarship by the University of Bristol and was accepted as a postgraduate student at Newnham College, Cambridge.

Beryl May Dent | |

|---|---|

Dent in 1928. | |

| Born | 10 May 1900 Chippenham, Wiltshire, England |

| Died | 9 August 1977 (aged 77) Sompting, West Sussex, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | |

| Awards | 1923: Ashworth Hallett scholarship |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

Other fields

|

| Institutions |

|

| Academic advisors | John Lennard-Jones |

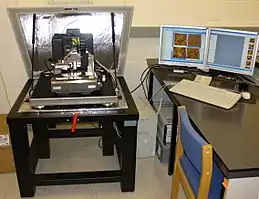

Dent returned to Bristol in 1925, after being appointed a researcher in the Physics Department at the University of Bristol, with her salary being paid by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. In 1927, John Lennard‑Jones was appointed Professor of Theoretical Physics, a chair being created for him, with Dent becoming his research assistant in theoretical physics. Lennard‑Jones pioneered the theory of interatomic and intermolecular forces at Bristol and she became one of his first collaborators. Lennard‑Jones and Dent published six papers together from 1926 to 1928, that were the foundation of her master's thesis, dealing with the forces between atoms and ions. Later work has shown that the results they obtained had direct application to atomic force microscopy by predicting that non-contact imaging is possible only at small tip-sample separations.

In 1930, Dent joined Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Company Ltd, Manchester, as a technical librarian for the scientific and technical staff of the research department. She became active in the Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux (ASLIB) and was honorary secretary to the founding committee for the Lancashire and Cheshire branch of the association. She served on various ASLIB committees and made conference presentations detailing different aspects of the company's library and information service. She continued to publish scientific papers, contributing numerical methods for solving differential equations by the use of the differential analyser that was built for the University of Manchester and Douglas Hartree. She was the first to develop a detailed reduced major axis method for the best fit of a series of data points.

Later in her career she became leader of the computation section at Metropolitan-Vickers, and then a supervisor in the research department for the section that was investigating semiconducting materials. Dent joined the Women's Engineering Society and published papers on the application of digital computers to electrical design. She retired in 1960, with Isabel Hardwich, later a fellow and president of the Women's Engineering Society, replacing her as section leader for the women in the research department. In 1962, she moved with her mother and sister to Sompting, West Sussex, and died there in 1977.

Early life

Beryl May was born on 10 May 1900, at Penley Villa, Park Lane, Chippenham, Wiltshire, the eldest daughter of Agnes Dent (1869–1967), née Thornley, and Eustace Edward (1868–1954).[1] She was baptised at St Paul's, Chippenham, on 8 June 1900.[2]:1 Agnes Thornley and Eustace Edward Dent had married at St Mary's Church, Goosnargh, near Preston, Lancashire, on 27 July 1898.[3] Thornley was educated at the Harris Institute, Preston, passing examinations in science and art.[4] She was a teacher at Attercliffe School, in northeast Sheffield, before moving to Goosnargh School, near her hometown of Preston, where her elder brother and sister, John William and Mary Ann Thornley, were the head teachers.[5][6] In March 1894, she had applied for the headship at Fairfield School, Cockermouth, making the shortlist, but the board decided to appoint a local candidate.[7]

On 18 March 1889, Eustace Edward Dent was appointed to a teaching assistant position at Portland Road School, in Calderdale, Halifax, after completing a teaching apprenticeship with the school board.[8][9] In the same year, Florence Emily Dent, Eustace's elder sister and Dent's aunt, was appointed head teacher at West Vale girls' school, Stainland Road, Greetland, moving from the Higher Board School at Halifax.[10] In August 1889, Eustace obtained a first class pass in mathematics from the Halifax Mechanics' Institute.[11][lower-alpha 1] He then enrolled on a degree course at University College, Aberystwyth, in the Education Day Training College.[lower-alpha 2] In January 1894, he was awarded a first by Aberystwyth, and a first in the external University of London examinations.[13][14][lower-alpha 3] His first teaching post was at Coopers' Company Grammar School, Bow, London,[15] before moving to Chippenham, where he was a senior assistant teacher at the Chippenham County School. After five years at Chippenham, he left in October 1901 to become head teacher of the then recently established Warminster County School, that adjoined the Athenaeum Theatre in Warminster.[16][17][18][lower-alpha 4] He was chair of the Warminster Urban District Council from 1920 to 1922,[lower-alpha 5] and remained as head teacher of the County School until his retirement in August 1929.[22][21][lower-alpha 6]

After moving from Chippenham, the Dent family lived at Boreham Road, Warminster, where houses were built in the early 19th century.[25][26][lower-alpha 7] In April 1907, the family moved to 22 Portway, Warminster, situated a short distance from the County School and the Athenaeum.[20]:264[27] Eustace was a regular cast member of the Warminster Operatic Society at the Athenaeum and other venues. Dent and her younger sister, Florence Mary, would often appear with him on stage in such operettas as Snow White and the seven dwarfs and the Princess Ju‑Ju (The Golden Amulet), a Japanese operetta in three acts by Clementine Ward.[28][29][30] In Princess Ju‑Ju, she played La La, one of the three maidens attendant on the Princess Ju‑Ju, and sang the first act solo, She must be demure.[31][32] In act two of the same musical, she performed in the fan dance, Spirits of the Night.[29][32][lower-alpha 8] She also acted in a scene from Tennyson's Princess at the County School's prize giving day on 16 December 1913.[35][lower-alpha 9]

Education

Warminster County School

Dent was educated at Warminster County School, where her father was head teacher. At school, she was close friends with her neighbour at Portway, Evelyn Mary Day, the eldest daughter of Henry George Day, a former butler to Colonel Charles Gathorne Gathorne‑Hardy, son of Gathorne Gathorne-Hardy, 1st Earl of Cranbrook.[36][37][lower-alpha 10] In August 1914, she passed the University of Oxford Junior Local Examination with first class honours, and on the strength of her examination result, she was awarded a scholarship by the County School. In 1915, she passed the senior examination with second class honours and a distinction in French, and subsequently, her scholarship was renewed.[38][39][40] She then joined the sixth form and won the school prize for French in December 1916.[41][lower-alpha 11] In March 1918, she applied for a scholarship in mathematics from Somerville College, Oxford, one of the first two women's colleges in Oxford. She was highly commended but was not awarded a scholarship nor an exhibition.[42]

University of Bristol

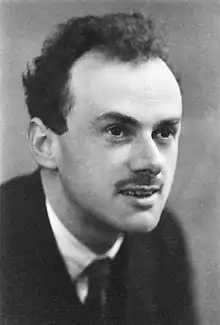

Dent was accepted on to the general Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree course at the University of Bristol and passed her intermediate degree examinations in June 1920.[lower-alpha 12] For the following academic year, she took the honours course in mathematics at Bristol.[44] After spending the summer of 1921 at her parent's home in Warminster,[45] she returned for the start of the 1921 to 1922 academic year to find that Paul Dirac had joined the mathematics course.[46][lower-alpha 13] Dent and Dirac were taught applied mathematics by Henry Ronald Hassé, the then head of the Mathematics Department, and pure mathematics by Peter Fraser. Both of them had come from Cambridge.[46] Fraser introduced them to mathematical rigour, projective geometry, and rigorous proofs in differential and integral calculus.[47][lower-alpha 14] Dent studied four courses in pure mathematics:

- Geometry of conics; Differential geometry of plane curves

- Algebra and trigonometry; Differential and integral calculus

- Analytical projective geometry of conics

- Differential equations; Solid geometry.[48]

There was a choice of specialisation in the final year; applied or pure mathematics. As the only official, registered fee-paying student, Dent had the right to choose, and she settled on applied mathematics for the final year. The department could offer only one set of lectures so Dirac also had to follow the same course.[49][lower-alpha 15] Dent studied four courses in applied mathematics:

- Elementary dynamics of a particle and of rigid bodies

- Graphical and analytical statics; Hydrostatics

- Dynamics of a particle and of rigid bodies

- Elementary theory of potential with applications to electricity and magnetism.[48]

Newnham College, Cambridge

In June 1923, she graduated with Dirac, gaining a Bachelor of Science (BSc) degree in applied mathematics with First Class Honours.[50][46][lower-alpha 16] On 7 July 1923, she was awarded the Ashworth Hallett scholarship by the University of Bristol and was accepted as a postgraduate student at Newnham College, Cambridge.[49][51][52][lower-alpha 17] Dent spent a year at Cambridge, leaving in 1924 without further academic qualification, prior to being appointed to a temporary position teaching science at Barnsley Girls' High School, Huddersfield Road, Barnsley.[52] Before 1948, Cambridge University denied women graduates a degree, although in the same year as Dent left Cambridge, Katharine Margaret Wilson was the first woman to be awarded a PhD at Cambridge.[54][lower-alpha 18]

Career

University of Bristol Department of Physics

In 1925, Dent was appointed a researcher in the Physics Department at the University of Bristol, with her salary being paid by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, the forerunner of the Science and Engineering Research Council (SERC).[56]:107[52][lower-alpha 19] In 1924, the University of Bristol Council had set aside a portion of a bequest from Henry Herbert Wills for the Department of Physics where Arthur Mannering Tyndall was building up a staff for teaching and research in the H. H. Wills Physics Laboratory, Royal Fort House Gardens.[58][lower-alpha 20] From August 1925, John Lennard‑Jones, Trinity College, Cambridge, was elected Reader in Mathematical Physics.[60][58] In March 1927, Lennard‑Jones was appointed Professor of Theoretical physics, a chair being created for him, with Dent becoming his research assistant in theoretical physics.[61][62]:24[63][lower-alpha 21] Lennard‑Jones pioneered the theory of interatomic and intermolecular forces at Bristol and Dent became one of his first collaborators.[58][46]

Lennard‑Jones and Dent published six papers together from 1926 to 1928, dealing with the forces between atoms and ions, with the objective of calculating theoretically the properties of carbonate and nitrate crystals.[46][64] Dent's thesis for her master's degree, Some theoretical determinations of crystal structure (1927), was the basis of the three papers that followed in 1927; with Lennard‑Jones, Crystal parameters, and with Lennard‑Jones and Sydney Chapman, Structure of carbonate crystals (1927) and Part II. Structure of carbonate crystals (1927).[lower-alpha 22] On 28 June 1927, she was awarded a MSc degree for her thesis and research work.[65] In 1927, the physics laboratory at Bristol had a surplus of funds, and so it was decided that the funds would be used to provide more technical help.[lower-alpha 23] Consequently, Dent was asked to combine her research duties with the post of part-time departmental librarian, the first appointment of librarian in the Department of Physics.[62]:26[1][lower-alpha 24]

Dent was now living at Clifton Hill House, the university hall of residence for women in Clifton.[66][lower-alpha 25] She had been appointed honorary secretary of the Bristol Cheeloo Association by March 1926.[69] The association's aim was to raise sufficient funds to support a chair of chemistry at Cheeloo University.[66] In an effort to publicise the cause and raise money, she presented to the local branch of the Women's International League in October 1928.[70] In 1927, she was one of eleven people elected to the standing committee of the University of Bristol's Convocation, the university's alumni association, and later, represented the Manchester branch of the association.[71][72][67] In 1928, Lennard‑Jones and Dent published two papers, Cohesion at a crystal surface (1928), and with Sydney Chapman, The change in lattice spacing at a crystal boundary (1928), that studied the force fields on a thin crystal cleavage.[73][74] Around this time, quantum mechanics was developed to become the standard formulation for atomic physics.[lower-alpha 26] Lennard‑Jones left Bristol in 1929 to study the subject for a year as a Rockefeller Fellow at the University of Göttingen.[76]

With her collaborator and advisor in Germany, Dent wrote one last paper before leaving the physics department at Bristol: The effect of boundary distortion on the surface energy of a crystal (1929) examined the effect of the polarisation of surface ions in decreasing the surface energy of alkali halides.[77] In December 1929, she resigned her position and it was accepted with regret by the Council of the University of Bristol.[78] She left Bristol for Stretford, Manchester, to become the technical librarian for the scientific and technical staff in the research department at Metropolitan-Vickers.[79]:232 In 1930, Lennard‑Jones returned to Bristol, as Dean of the Faculty of Science, and introduced the new quantum theories to the Bristol group.[76][58][lower-alpha 27] Marjorie Josephine Littleton was appointed as Dent's replacement on the 1 February 1930. She was the daughter of a local Bristol councillor and a graduate of Girton College, Cambridge. She was later Sir Neville Mott's co-author and research assistant in the Physics Department.[81][82]:517

Metropolitan-Vickers

Metropolitan-Vickers was a British heavy industrial firm, based at Trafford Park, Manchester. They were well known for industrial electrical equipment and generators, street lighting, electronics, steam turbines and diesel locomotives. They built the Metrovick 950, the first commercial transistorised computer.[83] In 1917, a Research and Education Department was established at the Trafford Park site, when the care of the library came within the remit of James George Pearce, a former engineer in the Transformer Department.[lower-alpha 28] He made the library the centre of a new technical intelligence section. In 1929, the technical intelligence section was substantially reorganised and expanded, and placed under the directorship of James Steele Park Paton.[79]:193[84] In January 1930, Dent joined the senior scientific and technical staff in the research at department Metropolitan-Vickers.[62]:49[79]:193 Technical librarianship emerged as a new scientific career in interwar Britain and rapidly became one of the few types of professional industrial employment that was routinely open to both women and men.[85]:301

By 1933, the Metropolitan-Vickers library had 3,000 engineering volumes and around the same number in pamphlets and patent specifications.[86] Besides covering electrical subjects, the library covered accountancy, employment questions, and subjects of interest to the sales department. It also issued a weekly bulletin, scrutinised patents, handled patents taken out by research staff, and exchanged information with associated companies.[87] From 1931 to 1936, Dent was honorary secretary to the founding committee for the Lancashire and Cheshire branch of the ASLIB.[88]:204–205 In 1932, the branch had twenty six members and had organised four meetings, including one addressed by Sir Henry Tizard, the then President of ASLIB. After the war, it formed the basis for the Northern Branch of the association.[89]:412 She was also a delegate at the fourteenth International Conference on Documentation and was invited to the Government's conference dinner on 22 September 1938 at the Great Dining Hall of Christ Church, Oxford.[90][lower-alpha 29] She served on various ASLIB committees and made conference presentations detailing different aspects of the company's library and information service.[79]:228[91]

Dent continued to publish papers in applied mathematics and contribute to papers on emerging computational technologies. In On observations of points connected by a linear relation (1935), she developed a detailed reduced major axis method for line fitting that built on the work of Robert Adcock and Charles Kummell.[92][93] For Myers, Hartree, and Porter, in The Effect of Space-Charge on the Secondary Current in a Triode (1937), she provided the key numerical integrations for differential equations to aid in the calculation of the space charge limitation of secondary current using a differential analyser.[94] In 1946, she was promoted to section leader of the company's new computation section. Her knowledge of higher mathematics meant that she was often asked to check the mathematics in papers for publication by engineers at Metropolitan-Vickers. For example, Cyril Frederick Gradwell, a graduate of Trinity College, Cambridge, asked her to scrutinise the algebraic part of his work in The Solution of a problem in disk bending occurring in connexion with gas turbines (1950).[95][lower-alpha 30]

In the latter half of her career, Dent became the section leader for the women in the research department that were working on semiconducting materials.[79]:233 She performed the Fourier analysis in Shorting and Field Corrections in Hall Measurements (1954), that developed a method for correcting the measured Hall effect in semiconductors for inhomogeneities in the applied magnetic field.[97] In 1958, she carried out computer calculations for the mechanical engineering team at the Nuclear Power Group, Radbroke Hall. Their paper outlined a procedure for calculating the theoretical deflection (bending) of a circular grid of support girders for a graphite neutron moderator in a gas-cooled reactor.[98] A general expression was derived from the central deflection of the grid and the maximum bending moment on the central cross-beam for a range of grid diameters.[99]

Dent joined the Women's Engineering Society and published papers on the application of digital computers to electrical design.[100][101] With Brian Birtwistle, she wrote programs for the Manchester University Ferranti Mark 1, that demonstrated that high speed digital computers could provide considerable assistance to the electrical design engineer.[102] Birtwistle would later have an extensive career in the computer industry, working at, amongst others, Honeywell Information Systems and ADP Network Services.[103] She retired from Metropolitan-Vickers in May 1960, with Isabel Hardwich, later a fellow and president of the Women's Engineering Society, replacing her as section leader for the women in the research department.[104][105]:243

Later life and death

Dent's father died on 24 June 1954, at their shared home, 529 King's Road, Stretford, with the funeral service taking place at St Matthew's Church, Stretford.[106] Dent had close links to St Matthew's; from 1956 to 1962, she served as a school manager for St Matthew's Church of England Primary School at Poplar Road, Stretford.[52] In 1962, she and her elderly mother, Agnes, moved from Stretford to 1 Cokeham Road, Sompting, a village in the coastal Adur District of West Sussex, between Lancing and Worthing.[107][108] Agnes died on 5 April 1967 and was cremated at the Downs Crematorium on 10 April 1967.[109][lower-alpha 31]

Dent died at her home in Sompting on 9 August 1977 (aged 77).[112][113] She donated her body for medical examination, on the understanding that her remains would be returned for a funeral service at St Mary's Church, Sompting, followed by cremation.[114] Her ashes were interred at Worthing Crematorium, in the Gardens of Rest, towards the Spring Glades, and her entry in the Book of Remembrance at the crematorium states:[115][116][lower-alpha 32]

Beryl May Dent 1900 – A real Christian loved by all – 1977.

There is also a memorial to her in the Order of St John, Hospitallers' Room, at St Mary's Church, where a carver chair bears a brass plaque with the following inscription:[117][lower-alpha 33]

In loving memory of Beryl Dent 1900 – 1977.

Dent never married, believing that getting married, and the subsequent pressures of family responsibilities, would be a "wastage" of a woman's training. However, she also believed that women leaving employment to get married would mean promotion opportunities for other women, and that married women would still be able to return to work in mid-life.[118] Her Christian faith is perhaps not surprising, given her father's work for the church in Warminster, and the era she grew up in, where religion pervaded social and political life.[119][120] However, it is notable that she remained a committed Christian while pursuing a scientific career. According to Steven Weinberg, science offers no support for belief in God, and that belief in God is unnecessary; a view shared by other scientists. However, Steve Ball, in an article that supports the science of prominent atheistic scientists, states that physics can actually fit well with biblical faith.[121][122]:2[lower-alpha 34]

Legacy

Atomic force microscopy

In 1928, Lennard‑Jones and Dent published two papers, Cohesion at a crystal surface (1928) and The change in lattice spacing at a crystal boundary (1928), that for the first time, outlined a calculation of the potential of the electric field in a vacuum, produced by a thin sodium chloride crystal surface.[73][74] They gave an expression for the electric potential produced by a system of point charges in vacuum (although not a real cubic sodium chloride ionic lattice).[123]:796–797 The expression for the potential in vacuum, , at the point r = {x, y, z}, near the cubic lattice of point ions with different signs, the charge , and the period a (a crystalline solid is distinguished by the fact that the atoms making up the crystal are arranged in a periodic fashion), can be represented in the form:[123]:797

-

(1)

- is the lateral vector that fixes the observation point coordinates in the sample plane.

- is the reciprocal lattice vector.

- s is the number of planes to be calculated inside the crystal; s set to zero would calculate the surface plane.

The expression sums the set of potential static charges for the surface and lower layers of the crystal. Lennard‑Jones and Dent showed that this expression forms a rapidly convergent Fourier series.[123]:797 Harold Eugene Buckley, a crystallographic researcher at the University of Manchester until his death in 1959,[124]:481 had suggested that the results obtained in Cohesion at a crystal surface (1928), should be treated with caution. For example, the contraction a crystal plane would suffer under the conditions prescribed would not be the same as that of a similar plane with a solid mass of crystal behind it. Another difficulty arises because calculation of crystal surface field force fields are so great that simplifying assumptions have to be made to render them capable of a solution.[125] However, later work by Cleveland, Radmacher, and Hansma, in Atomic Scale Force Mapping with the Atomic Force Microscope (1994), has shown that the Lennard‑Jones and Dent paper had direct application to atomic force microscopy by predicting that non-contact imaging is possible only at small tip-sample separations.[126]

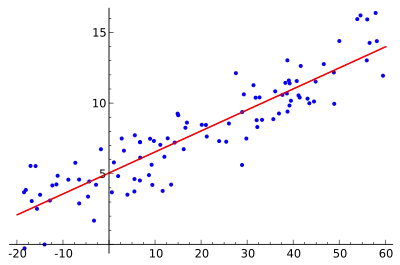

Reduced major axis regression

Richard J. Smith has stated that Dent, in On observations of points connected by a linear relation (1935), was the first to develop a reduced major axis (RMA) regressiom method for line fitting that built on the work of Robert Adcock in A Problem in Least Squares (1878) and Charles Kummell in Reduction of observation equations which contain more than one observed quantity (1879).[92][93] The theoretical underpinnings of standard least squares regression analysis are based on the assumption that the independent variable (often labelled as x) is measured without error as a design variable. The dependent variable (labeled y) is modeled as having uncertainty or error. Both independent and dependent measurements may have multiple sources of error. Therefore, the underlying least squares regression assumptions can be violated. RMA regression is specifically formulated to handle errors in both the x and y variables.[127]:1 If the estimate of the ratio of the error variance of y to the error variance of x is denoted by 𝜆, then the reduced major axis method assumes that 𝜆 can be approximated by the ratio of the total variances of y and x.[128] RMA minimizes both vertical and horizontal distances of the data points from the predicted line (by summing areas) rather than the least squares sum of squared vertical (y-axis) distances.[127]:2

Maurice Kendall and Alan Stuart showed that the maximum likelihood estimator of a likelihood function, depending on a parameter , satisfies the following quadratic equation:[129]:387

-

(2)

- where x and y are the and vectors in a covariance matrix giving the covariance between each pair of x and y variables.

Using the quadratic formula to solve for the positive root (or zero) of (2):[130]

-

(3)

Inspection of (3) shows that as 𝜆 tends to zero, the positive root tends to equal to , and as 𝜆 tends to plus infinity, the root tends to equal to .[130] Dent had solved the maximum likelihood estimator in the case where the covariance matrix is not known, that is, when the variances in the x and y variables are unknown.[131]:1049 Dent's maximum likelihood estimator is the geometric mean of and , equal to:[130]

- , where is positive.

Dennis Lindley repeated Dent's analysis and stated that Dent's geometric mean estimator is not a consistent estimator for the likelihood function, [132]:235–236, 241 and that the gradient of the estimate will have a bias, and this remains true even if the number of observations tends to infinity.[133]:15 Kenneth Alva Norton, a former consulting engineer with the then National Bureau of Standards, responded to Lindley, stating Lindley's own methods and assumptions lead to a biased prediction.[134] Furthermore, Albert Madansky noted that Lindley took the wrong root for the quadratic in (2) for the case where is negative.[135]:201–203 Subsequently, Theodore Anderson pointed out that the likelihood function has no maximum in this case, and therefore, there is no maximum likelihood estimator.[136]:3

Although Dent's solution has its theoretical limitations, it is of practical importance, as it likely represents the best a priori estimate if nothing is known about the true error distribution in the model. It is generally much less reasonable to assume that all the error, or residual scatter, is attributable to one of the variables.[133]:3[128]

Electrical design using digital computers

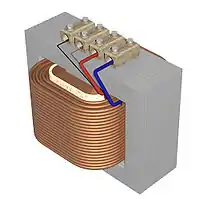

In the 1950s, British electrical engineers would rarely use a digital computer, and if they did, it would be to solve some complicated equation outside the scope of analogue computers. To a certain extent, engineers were deterred by the difficulty and the time taken to program a particular problem. Furthermore, the varied and often unique problems that arise in electrical design practice, together with the degree of uncertainty of the numerical data of many problems, accentuated this tendency. On 10 April 1956, Dent and Brian Birtwistle presented their paper, The digital computer as an aid to the electrical design engineer (1956), to the Convention on Digital Computer Techniques at the Institution of Electrical Engineers.[137] The paper was intended to show, by describing three relatively simple applications, that the digital computer could be a very useful aid to the electrical design engineer. The three example problems were:

- Impulse voltage distribution on transformer windings

- Supply frequency ripple on transductor performance

- Starting torque of a synchronous motor.[138]

The Manchester University Ferranti Mark 1 computer was used for the calculations in the three problems. Dent was allowed to use the University's library of subroutines, from which the following were taken and incorporated into the programs:[139]

|

|

Their paper was one of the first to recognise that high speed digital computers could provide considerable assistance to the electrical design engineer by carrying out automatically the optimum design of products.[102] Considerable research had been devoted to determining a transformer's internal transient voltage distribution. Early attempts were hampered by computational limitations encountered when solving large numbers of coupled differential equations with analogue computers.[140] It was not until Dent, with Hartill and Miles, in A method of analysis of transformer impulse voltage distribution using a digital computer (1958), recognised the limitations of the analogue models and developed a digital computer model, and associated program, where non-uniformity in the transformer windings could be introduced and any input voltage applied.[141]

Publications

Selected papers and academic articles

| Year | Title | Co-author(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1926 | The forces between atoms and ions. II | John Edward Lennard‑Jones | Extends earlier results to provide a complete table of forces between the monovalent and divalent ions of the inert gases.[142] |

| 1927 | Some theoretical determinations of crystal structure | Dent (sole author) | Dent's MSc thesis. It formed the basis of the three papers published in 1927.[143] |

| 1927 | Some theoretical determinations of the structure of carbonate crystals | John Edward Lennard‑Jones and Sydney Chapman |  Test tube with a sample of brown-red Ferrous carbonate. 3, a polyatomic ion, in iron(II) carbonate FeCO 3, or ferrous carbonate.[64] |

| 1927 | Some theoretical determinations of the structure of carbonate crystals. II | John Edward Lennard‑Jones and Sydney Chapman | Discusses the work required to separate iron(II) carbonate into its constituent iron(II) cations Fe2+ and carbonate anion.[64] |

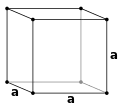

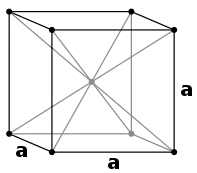

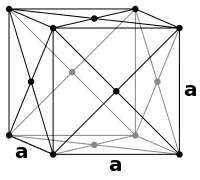

| 1927 | Some theoretical determinations of crystal parameters | John Edward Lennard‑Jones | Simple cubic Body-centred cubic Face-centred cubic Comparison of crystal cubic lattice structures. The surface plane of a face-centred cubic lattice was derived by Lennard‑Jones and Dent and has been used extensively in physisorption studies. They simplified the calculation of the Lennard-Jones potential by noting that the ions under study were isoelectronic with inert gas atoms, and thus, there was no need to introduce additional empirical L‑J parameters into the equation. In rock-salt or sodium chloride (halite) structure, each of the two atom types forms a separate face-centred cubic lattice. Examples of compounds with this structure include sodium chloride itself, along with the other alkali halides, and divalent metal oxides, sulphides, selenides, and tellurides.[144]:16[145][146]:682–683 |

| 1928 | Cohesion at a crystal surface | John Edward Lennard‑Jones | Calculation of the surface energy of solids. Shows that for an ionic substrate a charged particle would be most strongly adsorbed, but that the electrostatic forces were very short range, and for greater distances, were smaller than the van der Waals' forces. A dipole would be adsorbed in the same manner as a charged particle but much less strongly.[73] |

| 1928 | The change in lattice spacing at a crystal boundary | John Edward Lennard‑Jones and Sydney Chapman | Shows that when alkali metal halide crystals are put under tension along their length, they suffer a lateral contraction of the order of 6 percent.[74] |

| 1929 | The effect of boundary distortion on the surface energy of a crystal | Dent (sole author) | The effect of polarisation of surface ions in decreasing surface energy of the alkali halide crystals is studied. It is shown that for a series of alkali halide crystals, it is the deformability of the surface ions which largely controls the distortion at the surface. In general, close-packing and wide inter-planar spacing tend to lower the free surface energy in crystals.[77][147] |

| 1933 | The technical news bulletin and house journal of the Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Company | Dent (sole author) |  The conference was held at the Wills Hall, University of Bristol. |

| 1935 | On observations of points connected by a linear relation | Dent (sole author) | Dent was the first to describe and develop a detailed reduced major axis method for line fitting. The paper was sent to the Physical Society by Henry Ronald Hassé, Dent's former professor of applied mathematics at Bristol, on 10 July 1934. The paper was refereed by Alexander Aitken, and at the time of publication, commented on by William Edwards Deming.[92][150] |

| 1946 | The library and information service of the Metropolitan-Vickers Co. Ltd. | James Steele Park Paton | Describes the information service developed during the last thirty years to meet the needs of the research department at the Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Company. In response to a request from the senior staff, a weekly "Industrial Digest" was produced from 1945. The digest contained about fifty brief abstracts on factory processes and workshop practice.[151] |

| 1946 | What the industrialist expects of an information service | Sir Arthur Fleming |  The Polytechnic (now the University of Westminster) on Regent Street, where Dent and Fleming presented at the twenty first annual conference of ASLIB. |

| 1956 | The digital computer as an aid to the electrical design engineer | Brian Birtwistle | The value of the digital computer as an aid to the electrical design engineer is discussed in the light of the authors' extensive use of the Ferranti Mark 1 computer.[lower-alpha 36] Three examples are described:[137]

|

| 1956 | The authors' replies to the discussion on 'Engineering and scientific applications of digital computers' | Brian Birtwistle | Replies to questions on the digital computer as an aid to the electrical design engineer. Douglas Hartree suggests using an extension of Numerov's method to reduce the time taken to solve the second-order differential equations. Dent and Robinson also support Dr. Robert Kenneth Livesley's recommendation that engineering courses should take into account modern developments with regard to the application of digital computers to engineering practice.[153] |

| 1958 | Analysis of transformer impulse voltages by digital computer | Eric Raymond Hartill and James George Miles | A review of the paper below after it was published as an individual paper in December 1957 and republished in Part A, Power Engineering, Proceedings of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. Hartill and Miles also worked at Metropolitan-Vickers.[154][lower-alpha 38] |

| 1958 | A method of analysis of transformer impulse voltage distribution using a digital computer | Eric Raymond Hartill and James George Miles | The paper presents a method of impulse voltage calculation in which non-uniformity in the transformer windings could be introduced and input voltage applied. The derivation of the transformer circuit is discussed, together with a digital computer program for the solution of the resulting differential equations.[141][140] |

Publications detail

Dent

- Birtwistle, Brian; — (April 1956). "The digital computer as an aid to the electrical design engineer". Proceedings of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. Part B. Radio and Electronic Engineering. London. 103 (1S): 47–53. doi:10.1049/pi-b-1.1956.0008. ISSN 2054-0434. Paper No. 2092 M. The paper was first received 30 January 1956, and in revised form, 5 March 1956. It was published in March 1956 and was read at the Convention on Digital-Computer Techniques on 10 April 1956.

- Birtwistle, Brian; — (April 1956). "The authors' replies to the discussion on 'Engineering and scientific applications of digital computers'" (PDF). Proceedings of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. Part B. Radio and Electronic Engineering. London. 103 (1S): 82–83. doi:10.1049/pi-b-1.1956.0013. ISSN 2054-0434. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- — (1927). Some theoretical determinations of crystal structure. 25, 13 leaves (MSc). Bristol: University of Bristol Physics Library. OCLC 931574568. DM1961. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- — (1 October 1929). "LV. The effect of boundary distortion on the surface energy of a crystal". Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. London. 8 (51): 530–539. doi:10.1080/14786441008564909. ISSN 1941-5982. Communicated by J. E. Lennard‑Jones.

- — (January 1933). "The technical news bulletin and house journal of the Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Company". Report of Proceedings of the 10th Conference of the Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux. London: ASLIB. 10: 56–58. OCLC 652436848.

- — (1 January 1935). "On observations of points connected by a linear relation". Proceedings of the Physical Society. London. 47 (1): 92–108. Bibcode:1935PPS....47...92D. doi:10.1088/0959-5309/47/1/307. ISSN 0959-5309. Retrieved 15 July 2020. Communicated by Henry Ronald Hassé on 10 July 1934. Includes discussion by William Edwards Deming.

- —; Hartill, Eric Raymond; Miles, James George (1 May 1958). "Analysis of transformer impulse voltages by digital computer". Proceedings of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. London. 4 (41): 259–261. doi:10.1049/jiee-3.1958.0116. ISSN 2054-0612.

- —; Hartill, Eric Raymond; Miles, James George (October 1958) [First published December 1957]. "A method of analysis of transformer impulse voltage distribution using a digital computer". Proceedings of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. Part A. Power Engineering. London. 105 (23): 445–459. doi:10.1049/pi-a.1958.0080. ISSN 2054-040X.

- —; Paton, James Steele Park (1946). Libraries Committee, City Council. "The library and information service of the Metropolitan-Vickers Co. Ltd". Manchester Review. Public Library Review Autumn. Manchester: Manchester Public Libraries. 4: 236–238. ISSN 0025-2026. OCLC 1014381852.

- Fleming, Arthur; — (September 1946). Sanger, Margaret (ed.). "What the industrialist expects of an information service". Report of Proceedings of the 21st Conference of the Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux. London: ASLIB. 21: 47–56. OCLC 652436848. Held at Fyrie Hall, the Polytechnic, London, 14–15 September 1946.

- Lennard‑Jones, John Edward; — (3 August 1926). "The forces between atoms and ions. II". Proceedings of the Royal Society. Series A. Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. London. 112 (760): 230–234. Bibcode:1926RSPSA.112..230L. doi:10.1098/rspa.1926.0107. ISSN 0950-1207. JSTOR 94629. Retrieved 15 July 2020. Communicated by Sydney Chapman FRS. Received 8 June 1926.

- Lennard‑Jones, John Edward; —; Chapman, Sydney (1 January 1927). "Some theoretical determinations of the structure of carbonate crystals". Proceedings of the Royal Society. Series A. Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. London. 113 (765): 673–689. Bibcode:1927RSPSA.113..673L. doi:10.1098/rspa.1927.0015. ISSN 0950-1207. JSTOR 94650. Received 3 November 1926. Chapman provided the calculation of the electrostatic potential energy of an infinite array of electrical charges distributed according to the scheme determined by X-ray analysis.

- Lennard‑Jones, John Edward; —; Chapman, Sydney (1 January 1927). "Some theoretical determinations of the structure of carbonate crystals. II". Proceedings of the Royal Society. Series A. Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. London. 113 (765): 690–696. Bibcode:1927RSPSA.113..690L. doi:10.1098/rspa.1927.0016. ISSN 2053-9150. JSTOR 94650. Received 17 November 1926.

- Lennard‑Jones, John Edward; — (1 May 1927). "CXVI. Some theoretical determinations of crystal parameters". Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. London. 3 (18): 1204–1227. doi:10.1080/14786440508564290. ISSN 1941-5982.

- Lennard‑Jones, John Edward; — (1928). "Cohesion at a crystal surface". Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions. London. 24: 92–108. doi:10.1039/tf9282400092. ISSN 0014-7672. Retrieved 15 July 2020. Received 10 November 1927.

- Lennard‑Jones, John Edward; —; Chapman, Sydney (1 November 1928). "The change in lattice spacing at a crystal boundary". Proceedings of the Royal Society. Series A. Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. London. 121 (787): 247–259. Bibcode:1928RSPSA.121..247L. doi:10.1098/rspa.1928.0194. ISSN 2053-9150. JSTOR 95072. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

Dent as mathematician and programmer

- Edwards, John Charles Manson; Gill, Samuel Sidney; Perkins, Stanley (December 1958). "A Method of Calculating the Deflection of the Graphite Support Grid for a Gas Cooled Reactor". Civil Engineering and Public Works Review. London: Lomax, Erskine & Company Ltd. 53 (630): 1400–1402. ISSN 0009-7861. OCLC 220831595.

- Flanagan, William Francis; Flinn, Paul Anthony; Averbach, Benjamin Lewis (1 June 1954). "Shorting and Field Corrections in Hall Measurements". Review of Scientific Instruments. 25 (6): 593–595. Bibcode:1954RScI...25..593F. doi:10.1063/1.1771138. ISSN 0034-6748.

- Gradwell, Cyril Frederick (1 July 1950). "Asymmetrical Bending of Tapered Disks: The Solution of a problem in disk bending occurring in connexion with gas turbines". Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology. 22 (7): 209–212. doi:10.1108/eb031926. ISSN 0002-2667.

- Myers, David Milton; Hartree, Douglas Rayner; Porter, Arthur (1937). "The Effect of Space-Charge on the Secondary Current in a Triode". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 158 (893): 23–37. doi:10.1098/rspa.1937.0002. ISSN 0080-4630. JSTOR 96742.

ASLIB

- Fleming, Arthur; — (5 October 1946). Gale, Arthur James Victor (ed.). "Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux. Annual Conference" (PDF). Nature. London. 158 (4014): 491–492. doi:10.1038/158490b0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4099552. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

Women's Engineering Society

- — (1957). Cowper-Coles, Constance Hamilton (ed.). "Opportunities in the Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Company's Research Department for Girls of Good Scientific Education". The Woman Engineer. Autumn 1957 (pages 151 to 154 in the volume). London. 8 (6): 9–12. ISSN 0043-7298. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

See also

- Arthur Fleming

- Ferranti Mark 1

- Isabel Hardwich

- Metropolitan-Vickers

- Cecil Frank Powell and Herbert Wakefield Banks Skinner were colleagues of Dent at the Wills Physical Laboratory, Bristol, in the late 1920s

- University of Bristol

Footnotes

- His siblings took the mathematics examination at the same time.[11]

- See The Day Training College: a Victorian innovation in teacher training.[12]

- Aberystwyth originated as a college teaching external degrees of the University of London. See University of London Worldwide history of the external examination system.

- In 1897, the Government Education Inspectors insisted the Athenaeum must expand if it was to continue as a centre of learning. An initial plan to add a floor to the building was rejected in favour of adding a new adjoining building at a cost of £3,000. The new school also made use of the first floor classrooms in the Athenaeum.[19][20]:263

- There is a portrait photograph of Eustace, as chair of the council, in the cafe area of the Civic Centre in Sambourne Road, Warminster.[21]

- The school closed at the end of the summer term 29 July 1931, after the Wiltshire County Council Education Authority built a new secondary school for Warminster.[23] The building was used as the town library until 1958, and then by Warminster Youth Centre, but is now owned and managed by the Athenaeum Trust.[24]

- A Warminster town guide of 1924 described Boreham Road as a modern residential quarter of semi-detached villas, pretty gardens, with a tree lined footpath blending the rural with the urban.[26]

- At the end of the musical, the national anthem of Japan was sung, followed by the British national anthem, and the flags of the Allies were waved from the stage.[29] The Belgian flag was held by a young refugee, Alphonse Cambier, who, with three others, were attending the County School.[29] Germany had invaded Belgium on 4 August 1914, forcing Belgians to flee, with the United Kingdom home to 250,000 Belgian refugees during World War I. Lord Bath placed his vacant houses in the district at their disposal. Amongst others, two large houses in Warminster were made available, one in the Market Place, and one in Silver Street.[33][34]

.jpg.webp) Market Place in Warminster.

Market Place in Warminster. - Probably a scene from Princess Ida, the comic opera adaptation by Gilbert and Sullivan.

- Dent was a bridesmaid at Evelyn's wedding to Maurice Philip Young, a pharmacist, at the Minster Church of St Denys, Warminster, on 7 June 1926. At the time of her marriage, Evelyn was an assistant mistress at the Central County School, Church Road, Bexleyheath. Dent wore printed silk, with a shaded hat to match, and pink pearls, the gift of the bridegroom. She was known to friends and family as May Dent.[36]

- Dent's sister, Florence Mary, won the same prize for the year below.[41]

- The University of Bristol was the first higher education institute in England to admit women on an equal basis to men.[43]

- The course of mathematics at Bristol University normally lasted three years, but because of Dirac's previous training, the Department of Mathematics had allowed him to join in the second year.[46]

- Dirac would later say that Peter Fraser was the best teacher he had ever had.[46]

- Her relations with Dirac were strictly formal; they seldom spoke to each other.[48]

- Dent's sister, Florence Mary, graduated at the same time with a Bachelor of Arts degree.[50]

- The scholarship was open to female graduates of a recognised college or university, and worth £45 at the time.[53]

- Wilson later became a successful writer and poet. Wilson's dissertation, Music and English Poetry, featured at The Rising Tide: Women at Cambridge exhibition from October 2019.[54][55]

- Paul Dirac was also in receipt of a Research Council grant at this point with his research interests listed under Dent's entry in the Research Council's report for the year 1925 to 1926.[57]

- Tyndall became the "father" of the School of Physics. A lecturer and then professor who researched the mobility of ions in gases, Tyndall persuaded the Bristol industrialist Henry Herbert Wills to endow a purpose-built physics laboratory.[59]

- This was the first appointment of a professor of theoretical physics in the United Kingdom.[59]

- Sydney Chapman was Lennard‑Jones's PhD thesis advisor at Trinity College, Cambridge.[58]

- Despite the fact that the department had acquired a second professor and two research fellows.[62]:26

- The library had been named after Maria Mercer, the last surviving daughter of John Mercer, a Lancashire weaver who taught himself sufficient chemistry to be elected to a Fellowship of the Royal Society in 1852.[56]:3 Mercer was the inventor of the process of treating cotton known as mercerisation, and had amassed a considerable fortune. When Maria died, on 22 February 1913 at Clayton-le-Moors, aged 93, her trustees offered "not less than £5,000" to the University of Bristol, towards the endowment of a Chair of Chemistry.[56]:3

- May Christophera Staveley was her warden and tutor at Clifton Hill House. Dent returned to Bristol on 22 December 1934 for Staveley's funeral.[67] Dent was a member of the Clifton Hill House Old Students Association.[68]

- See the Fifth Solvay Conference in 1927.[75]

- In 1932, Lennard‑Jones was elected to the Plummer Chair of Theoretical Chemistry in the University of Cambridge: The first person to hold a Chair of Theoretical Chemistry anywhere in the world.[58] John Murrell has described Lennard‑Jones as "the father of British quantum chemistry".[80]

- Pearce was later a liaison engineer for European and American companies at Metropolitan-Vickers. He was also Director and Secretary of the British Cast Iron Research Association.[84]

- Earl Stanhope, President of the Board of Education, was in the chair at the dinner.[90]

- Along with Dent, Cyril Gradwell was one of the first programmers of the Ferranti Mark 1 computer. He wrote system software routines (for example Input G and Reciprocal G) that had advantages over the original versions written by Alan Turing. He wrote Mark I programs for Ferranti's guided missile work for the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough, and on cotton spinning applications for the British Cotton Industry Research Association's Shirley Institute at Didsbury.[96]

- Dent's sister, Florence Mary, also lived at the house until her death on 13 September 1986 (aged 84).[110] The move to Sompting was likely made after Florence retired from working life on 22 September 1961. She had been a secretary for the Withington Friendly Burial Collecting Society, Withington, and after its takeover in 1954, for Liverpool Victoria.[111]

- Dent is interred in row 11, plot 32, on a mowed lawn area, where the markers are in the form of small brass plaques set into the lawn, approximately 15 by 10 cm (6 by 4 in) in size. Dent's sister, Florence Mary, is also interred at the crematorium.[116]

- Similarly, Dent's mother, Agnes, is remembered on a brass plaque at the east end of the choir stall.[117]

- See also Has Physics Made Philosophy and Religion Obsolete? (2012) by Ross Andersen and David Albert's review of A Universe From Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather Than Nothing (2012) by Lawrence Krauss.

- The conference was held at the Wills Hall, University of Bristol, with Dent returning to Bristol for the first time since 1929 after resigning her position in the Physics Department.[148]

- See also the history of the transistor computer.

- See the 1958 paper, A method of analysis of transformer impulse voltage distribution using a digital computer.

- James George Miles served in the electrical branch of the Royal Naval Reserve, before studying at Brighton Technical College, graduating in 1948. After a college apprenticeship with Metropolitan-Vickers, he joined their staff at Manchester. He was awarded an Associated Electrical Industries Fellowship in 1950, and spent one year studying power-system analysis with British Thomson-Houston, before returning to Manchester.[155]

References

- Department of Physics (2003). Beryl Dent at the University of Bristol Department of Physics (Document). Bristol: University of Bristol Physics Library. DM1961/2. Retrieved 1 February 2021. Includes copy of Beryl May Dent's birth certificate.

- Ranger, Ruth (2014). "St Paul's Baptisms 1900–1905" (PDF). Wiltshire Online Parish Clerks. Chippenham. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Lancashire Online Parish Clerks (1898). "Marriages at St Mary the Virgin in the Parish of Goosnargh 1837–1915". Lancashire Online Parish Clerks. Goosnargh. Archived from the original on 29 January 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "The Harris Institute. Distribution of Prizes and Speech by the Earl of Derby". Preston Chronicle. 2 February 1889. p. 5. OCLC 1098850069. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Goosnargh. Annual Parish Tea-Party". Preston Herald. 27 January 1894. p. 2. OCLC 751660068. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Concert and Presentations at Goosnargh". Preston Herald. 26 July 1899. p. 5. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Cockermouth and Papcastle School Board". West Cumberland Times. 17 March 1894. p. 3. OCLC 1016277450. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "School Board Meetings. Halifax". Halifax Courier. 23 March 1889. p. 6. Retrieved 25 October 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Bull, Malcolm (22 October 2020). "Schools & Sunday Schools. Portland Road Board School, Claremount". Calderdale Companion. Halifax. Ref 18-136. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- "West Vale. Appointment of Mistress". Halifax Courier. 12 January 1889. p. 5. OCLC 18562459. Retrieved 25 October 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Halifax Mechanics' Institution". Halifax Courier. 31 August 1889. p. 3. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Thomas, John Bernard (1 October 1978). "The Day Training College: a Victorian innovation in teacher training". British Journal of Teacher Education. London. 4 (3): 249–261. doi:10.1080/0260747780040309. ISSN 0305-8913.

- "University of London. Matriculation Examination". The Welshman. 28 July 1893. p. 6. OCLC 52194901. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "University College, Aberystwyth. Day Training Department". Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald. 19 January 1894. p. 3. OCLC 57965341. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Year Book Press (1916). "Part II: Educational Directory of Masters in Secondary and Technical Schools, University Professors, Lecturers, and Others Connected with Education". The Schoolmasters' Yearbook and Educational Directory: A Reference Book of Secondary and University Education in England and Wales. London. p. 158. OCLC 7974973.

- "Chippenham District County School". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 1 May 1897. p. 4. OCLC 750854211. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Warminster. Technical Education". Salisbury and Winchester Journal. 26 October 1901. p. 8. OCLC 12116464. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Technical Education in Wilts". The Salisbury Times. 22 November 1901. p. 6. OCLC 20135569. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Warminster Athenaeum Centre (2020). "A brief history of the Warminster Athenaeum site". The Athenaeum Centre. Warminster. Archived from the original on 25 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Kelly's Directory (1911). "Kelly's Directory of Wiltshire". specialcollections.le.ac.uk. London. pp. 263–264. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Chairmen's Portrait Collection. Forty Years of Council Service Perpetuated. Unveiling by Lord Bath". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 25 May 1935. p. 4. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Headmastership of the County School". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 10 August 1929. p. 2. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "County School: Prize Distribution. The School's Impending Closure". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 27 December 1930. p. 9. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Murray, Robin (8 July 2016). "Big plans for Warminster Athenaeum after funding approved". Wiltshire Times. Warminster. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Local News. Fire". Warminster and Westbury Journal, and Wilts County Advertiser. 11 July 1903. p. 4. OCLC 751039353. Retrieved 5 September 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Then & Now – Boreham Road, Warminster". Wiltshire Times. 9 August 2007. Archived from the original on 5 September 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- "Christ Church Vestry Meeting". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 13 April 1907. p. 6. Retrieved 26 August 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Operetta at St John's". Warminster and Westbury Journal, and Wilts County Advertiser. 29 February 1908. p. 5. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Princess Ju Ju. Good Performance by Secondary School". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 28 November 1914. p. 6. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Howell, Danny (March 1987). "Yesterday's Warminster: The Warminster Operatic Society". dannyhowell.net. Warminster. OCLC 17674330. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Library of Congress; Copyright Office (April 1902). Catalog of copyright entries. 32. Washington: United States Government Printing Office. p. 1043. OCLC 847960278. Retrieved 5 September 2020. Class C. Musical Compositions. April–June Second Quarter 1902

- Guide to Musical Theatre (2020). "Princess Ju‑Ju or The Golden Amulet (O Mamori)". The Guide to Musical Theatre. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- "Belgian Refugees Expected. Lord Bath Getting Houses Ready". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 5 September 1914. p. 5. Retrieved 5 September 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Winterman, Denise (15 September 2014). "World War One: How 250,000 Belgian refugees didn't leave a trace". BBC News Magazine. London. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- "Secondary School Prize Distribution. The Admission of New Pupils". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 20 December 1913. p. 12. Retrieved 26 August 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

-

"Wedding at the Minster". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 12 June 1926. p. 4. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

May Dent, a Warminster County School fellow scholar and daughter of Mr. E. E. Dent (headmaster).

- The Weald (5 April 1891). "Thornhill (also known as Fowle Farm) Ashurstwood, East Grinstead". The Weald. Weald. Database version 13.6, EG.Thrnhl. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "Warminster Secondary School Prize Distribution". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 11 December 1915. p. 3. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Oxford Local Examinations. Trowbridge Centre. Juniors". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 29 August 1914. p. 5. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Education in Wilts. Award of Scholarships". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 7 August 1915. p. 11. Retrieved 22 August 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Secondary School Prize Distribution". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 16 December 1916. p. 10. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Somerville College Awards". The Times (41750). 29 March 1918. p. 7. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- University of Bristol (2019). "Women: Our history". www.bristol.ac.uk. Bristol. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "University of Bristol". Western Daily Press. 24 June 1920. p. 5. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Wiltshire County School Sports". Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser. 30 July 1921. p. 8. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Mehra, Jagdish; Rechenberg, Helmut (1 December 1982). "I Paul Dirac's Intellectual Development. I.3 Studying Applied Mathematics". Part 1: The fundamental equations of quantum mechanics. 4. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-387-90680-5. OCLC 1149230386. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Mehra, Jagdish (2001). The Golden Age of Theoretical Physics. 1. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 671. ISBN 978-981-281-058-8. OCLC 8603715103. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Farmelo, Graham (4 August 2009). "4. September 1921 – September 1923". The Strangest Man: The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac, Quantum Genius. London: Faber and Faber. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-465-01827-7. OCLC 1052113037. See The Strangest Man.

- Dalitz, Richard Henry (1990). "10. Another side to Paul Dirac. Dirac's engineering training". In Kurşunoğlu, Behram Nazim; Wigner, Eugene Paul (eds.). Reminiscences about a great physicist: Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-521-34013-7. OCLC 1106876593. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "University of Bristol. Results of Examinations for Degrees". Western Daily Press. 28 June 1923. p. 7. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "University News. Bristol July 7". The Times (43388). 9 July 1923. p. 19. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Newnham College (1963). Newnham College Register 1871–1923. 1871–1950. 1. Cambridge. p. 392. OCLC 22067783. Barcode 7019411065, Call number 378.4259. Bristol Central Lending Library Adult Reference.

- Institute of International Education (1929). Fellowships and scholarships open to American students for study in foreign countries. New York. p. 46. hdl:2027/mdp.39015035852824. OCLC 4560230.

-

Rowe, Jenny (2019). "The fight for rights: The history of women at Cambridge University". Britain - The Official Magazine. London: Chelsea Magazine Company. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

150 years since women were first admitted to the University of Cambridge, how have things changed?

- "University News. Vice-Chancellorship of Cambridge. Cambridge, June 5". The Times (43671). 6 June 1924. p. 16. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Thompson, Norman (October 1992). "The History of the Department of Physics in Bristol: 1948 to 1988" (PDF). University of Bristol Department of Physics. Bristol. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- Research Council (1927). "Appendix VII List of Publications by Individuals in Receipt of Grants, Brought to the Notice of the Department During the Year". Report of the Committee of the Privy Council for Scientific and Industrial Research for the Year 1925–1926. Reports of Commissioners. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO). p. 146. hdl:2027/uiug.30112045124630. OCLC 784035420. Page 608 in volume.

- Mott, Nevill Francis (1 November 1955). "John Edward Lennard‑Jones, 1894–1954". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. London. 1: 175–177. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1955.0013.

- University of Bristol (2018). "History of the School of Physics". www.bristol.ac.uk. Bristol. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Nature (1 February 1925). "University and Educational Intelligence". Nature. London. 115 (2887): 320–320. Bibcode:1925Natur.115..320.. doi:10.1038/115320a0. ISSN 1476-4687. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "University of Bristol. Department of Physics". Western Daily Press. 31 March 1927. p. 9. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Tyndall, Arthur Mannering (August 1956). "A History of the Department of Physics in Bristol 1876–1948. With personal reminiscences" (PDF). University of Bristol Department of Physics. Bristol. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "Bristol University. New Physics Laboratory. Description of the Building". Western Daily Press. 30 September 1927. p. 9. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Mellor, Joseph William (July 1935). A Comprehensive Treatise on Inorganic and Theoretical Chemistry. 14. London: Longmans, Green & Co. pp. 359–3361. OCLC 704414607. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- "Bristol University. Degree Pass Lists. Degree of M.Sc". Western Daily Press. 28 June 1927. p. 8. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "The Bristol Cheeloo Association". Western Daily Press. 11 December 1926. p. 4. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Friends' Tribute at Funeral of Miss M. C. Staveley". Western Daily Press. 24 December 1934. p. 10. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Clifton Hill House OSA (January 1930). Clifton Hill House Old Students Association Circular Letters (Group D) (Letter book). Bristol: University of Bristol. DM2227/5/3. Retrieved 7 September 2020. Written by members of the Clifton Hill House Old Students Association which were sent on to each person in a group, so that they could find out what their friends were doing. There are two volumes for Group D covering the period January 1930 to February 1938.

- "Letters to the Editor. Bristol Cheeloo Association". Western Daily Press. 5 March 1927. p. 5. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Women's International League". Western Daily Press. 1 November 1928. p. 7. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- University of Bristol (1928). "Convocation Elections". Calendar of the University of Bristol. Bristol: J. W. Arrowsmith Ltd: 62. ISSN 0305-3334. OCLC 924741357.

- "University Of Bristol. Association of Alumni Annual Dinner". Western Daily Press. 1 November 1927. p. 3. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Weaver, Clark (1960). "Adhesion of Thin Films". In Thomas, Émile (ed.). Proceedings of the First International Congress on Vacuum Techniques 10–13 June 1958. Advances in vacuum science and technology. 2. Oxford: Pergamon Press. p. 734. OCLC 1145776896. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Davey, Wheeler Pedlar (1934). "XII The Mechanism of Crystal Growth and its Consequences". A study of crystal structure and its applications. London: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. p. 383. OCLC 1087607482. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Beenakker, Carlo (2009). "Lorentz & the Solvay conferences". Leiden Institute of Physics of the Leiden University. Leiden. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Lennard‑Jones, Sir John Edward (1929). The Papers of Sir John Edward Lennard‑Jones 1906–1955 (4 archive boxes). Cambridge: Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge University Library. GBR/0014/LEJO. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Clark, Cecil Henry Douglas (1934). The electronic structure and properties of matter; an introductory study of certain properties of matter in the light of atomic numbers. London: Chapman and Hall Ltd. p. 326. hdl:2027/wu.89100400514. OCLC 8102373.

- "Anonymous Gift of £5,000 to Bristol University". Western Daily Press. 19 December 1929. p. 7. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Black, Alistair; Muddiman, Dave; Plant, Helen (2007). The Early Information Society: Information Management in Britain before the Computer. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-4279-4. OCLC 255622593. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Anders, Udo (17 May 2000). "Interview with Professor John N. Murrell at the University of Sussex, Brighton". Quantum Chemistry History. Brighton. Archived from the original on 13 November 2006. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Davis, Ann Elizabeth Leighton (May 2004). "Davis Archive: Mathematical Women in the British Isles, 1878–1940. Marjorie Josephine Littleton". Maths History St Andrews. St Andrews. ESRC: Reference Number 3654. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020. The Data Archive, University of Essex, Wivenhoe Park, Colchester, CO4 3SQ.

- Mott, Nevill Francis (1 January 1989). "Defect physics and chemistry: some problems awaiting a solution". Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions. 2. Molecular and Chemical Physics. London. 85 (5): 517–520. doi:10.1039/F29898500517. ISSN 0300-9238.

- Grace's Guide (2020). "Metropolitan-Vickers". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Exeter. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Science and Industry Museum (1996). "The Principles of Apprentice Training". archives.sciencemuseumgroup.ac.uk. Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Co. Ltd. Manchester. YA1996.1735/MS0531/59/3. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- Plant, Helen (1 June 2005). "Women scientists in British industry: technical library and information workers, circa 1918–1960". Women's History Review. New York: Routledge. 14 (2): 301–322. doi:10.1080/09612020500200424. ISSN 0961-2025. S2CID 143781423.

- Philip, Alex John, ed. (1933). "Libraries, Museums and Art Galleries in the British Isles". The Libraries, Museums and Art Galleries Year Book. London: Simpkin, Marshall, & Co. Ltd.: 131. ISSN 0075-899X. OCLC 1009021168. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Barnard, Cyril Cuthbert; Roberts, Arthur Denis (1936). Esdaile, Arundell James Kennedy; Pafford, John Henry Pyle (eds.). The Years Work in Librarianship. 9. London: The Library Association. p. 40. OCLC 1463596. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Brightman, Rainald (1 March 1956). "The Northern Branch: Retrospect and Prospect". Report of Proceedings of the Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux. ASLIB. 8 (3): 204–211. doi:10.1108/eb049598. ISSN 0001-253X.

- Muddiman, Dave (14 February 2005). "A new history of ASLIB, 1924–1950". Journal of Documentation. Leeds. 61 (3): 402–428. doi:10.1108/00220410510598553. ISSN 0022-0418. Accepted 17 November 2004.

- "Court Circular". The Times (41750). 23 September 1938. p. 15. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Dent 1933, p. 56.

- Smith, Richard Jay (2009). "Use and misuse of the reduced major axis for line-fitting". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Washington. 140 (3): 477. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21090. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 19425097.

- Choudhary, Pankaj Kumar; Nagaraja, Haikady Navada (2017). "1. Introduction". Measuring agreement: models, methods, and applications. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-118-55324-4. OCLC 1031484921.

- Froese Fischer, Charlotte (2003). Douglas Rayner Hartree: his life in science and computing. London: World Scientific. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-981-279-501-4. OCLC 666958945. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Gradwell 1950, p. 212.

- Lavington, Simon (2019). "17.2 Ferranti Programmers". Early computing in Britain: Ferranti Ltd. and government funding, 1948–1958. Colchester: Springer Nature. p. 355. ISBN 978-3-030-15103-4. OCLC 1107699799.

- Flanagan, Flinn & Averbach 1954, p. 595.

- Edwards, Gill & Perkins 1958, p. 1402.

-

Building Research Station (May 1959). Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. "Theory and Performance of Structures". Building Science Abstracts. 695–868. Garston: Her Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO). 32 (5): 139. hdl:2027/uiug.30112057110048. ISSN 0007-3636. OCLC 969454527. 747. UDC: 539.1.

A method of calculating the deflection of the graphite-support-grid for a gas-cooled reactor.

- Cooper, Joan Frances, ed. (1948). "Manchester Branch Report, 1947–1948". The Woman Engineer. Summer 1948 (page 264 in the volume). London. 6 (12): 216. ISSN 0043-7298. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Dent 1957.

- Birtwistle & Dent 1956a, pp. 52–53.

- Peltu, Malcolm, ed. (29 September 1977). "Two board appointments at IBM (UK)". Computer Weekly. Vol. 23 no. 569. London: IPC Electrical Electronic Press Ltd. p. 10. ISSN 0010-4787. OCLC 1039292399. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- Reynolds, John Donald, ed. (1960). "Appointments and Retirements and Obituaries". The Years Work in Librarianship. Fourth series. 62. London: The Library Association. p. 3. ISSN 0024-2195. OCLC 1696780.

- Jackson, Veronica Mary (2016). Metropolitan-Vickers: Arthur Fleming's influence on the origins and evolution of apprentice training and technical education, with particular reference to female college and student apprentices between 1945–1967 (PhD). Department of History, Politics and Philosophy, Manchester Metropolitan University. OCLC 1064617499. Retrieved 29 May 2019. See Part Three – Isabel Hardwich: A WES stalwart at Metrovicks.

-

"Deaths". The Guardian. 25 June 1954. p. 12. OCLC 28108425. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

DENT-On June 24, at 529 Kings Road, Stretford, EUSTACE EDWARD, aged 85 years the dearly loved husband of Agnes Dent. Service at St Matthew's Church on Tuesday, June 29, at 10 50 a.m., prior to committal at Manchester Crematorium at 11 20 a.m.

- BT Archives (September 1961). Manchester and Stoke-On-Trent Telephone Directory. British Phone Books 1880–1984 (Online database). 11. Stretford: BT Heritage. p. 207.

- BT Archives (May 1963). Brighton, Canterbury and Tunbridge Wells Telephone Directory. British Phone Books 1880–1984 (Online database). 4. Lancing: BT Heritage. p. 105.

-

"Deaths". The Guardian. 7 April 1967. p. 2. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

DENT-On April 5, peacefully, at home 1 Cokeham Road Sompting, Lancing, AGNES aged 97 years widow of Eustace Edward DENT and beloved mother of Beryl May and Florence Mary. Service at St Mary's Church Sompting, on Monday, April 10, at 2:15 pm followed by cremation at the Downs Crematorium, Brighton.

- "No. 50671". The London Gazette. 1 October 1986. p. 12718.

- Withington Friendly Society (1954). "Withington Friendly Burial Collecting Society. 1931 – 1954" (Collection). London: London Metropolitan Archives. CLC/155 (former reference MS 35152). Retrieved 13 September 2020.

-

Lucas, Sue, ed. (1978). "Obituary". The Woman Engineer. Spring 1978 (page 64 in the volume). London. 12 (7): 4. ISSN 0043-7298. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

Miss Beryl May Dent ... who became associates of the Society in 1956.

- Probate Service (1977). "Probate record for Beryl May Dent". Probate Service. London. p. 2166. 770511267B. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Gates and Moloney Solicitors (31 October 1975). Beryl May Dent (Will and testament). Edward Victor Kemp, Florence Mary Dent. Lancing: Probate Service. p. 1. 770511267B.

- Worthing Crematorium (9 August 1977). "Worthing Crematorium Online Book of Remembrance, Volume 1". Remembrance Books. Worthing. p. 444. Archived from the original on 2 September 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- Worthing Crematorium (2 September 2020). Extract from Cremation Register. Worthing: Worthing Borough Council. Dent, Beryl May, Gardens of Rest, Spring Glades, row 11, plot 32.

- Sussex Family History Group (May 2003). Sompting St Mary Transcriptions. Sompting and Lancing Pastfinders. Brighton: Sussex Family History Group. p. 31. Church15 and Church37. Credit: Eileen Colwell, Secretary, Lancing & Sompting Pastfinders, who researched Dent's memorial.

- Dent 1957, p. 12.

- "Christ Church. Congregational & Vestry Meetings". Warminster and Westbury Journal, and Wilts County Advertiser. 6 May 1905. p. 4. Retrieved 7 September 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Evans, Richard John (14 March 2011). "The Victorians: Religion and Science". Gresham College. London. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- Weinberg, Steven (25 September 2008). "Without God". The New York Review of Books. New York. ISSN 0028-7504. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- Ball, Steve (2014). "A Christian Physicist?" (PDF). LeTourneau University. Longview. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020. Chapter of LeTourneau University Integration of Faith and Learning.

- Dorofeev, Illarion Anatol'evich; Vinogradov, Evgeny Andreyevich (1 September 2012). "Structure of Electromagnetic Fields near the Surface of an Ionic Crystal". Journal of Surface Investigation. X-ray, Synchrotron and Neutron Techniques. Moscow: Pleiades Publishing Ltd. 6 (5): 796–804. doi:10.1134/S1027451012100059. ISSN 1819-7094. S2CID 95542444.

- Deer, William Alexander (1961). "Memorial of Harold Eugene Buckley" (PDF). American Mineralogist. March–April 1961. Part 2. Chantilly. 46 (6): 481–484. ISSN 1945-3027. OCLC 01480430. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- Buckley, Harold Eugene (1951). "6 Recent Theories of Crystal Growth". Crystal Growth. New York: Wiley. p. 178. OCLC 574492499. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Cleveland, Jason Paul; Radmacher, Manfred; Hansma, Paul Kenneth (1994). Office of Naval Research. "Atomic Scale Force Mapping with the Atomic Force Microscope". Applied Sciences. NATO ASI Series E. Santa Barbara: University of California, Department of Physics: 1. Bibcode:1994asfm.book.....C. OCLC 831936519. Technical Report No. 13. DTIC ADA284940. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Harper, William Victor (15 July 2014). "Reduced Major Axis Regression: Teaching Alternatives to Least Squares". Proceedings of the International Conference on the Teaching of Statistics. ICOTS 9 2014. Ohio: International Association for Statistical Education. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-1-118-44511-2. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Mark, David Michael (1984). "Some Problems With the Use of Regression Analysis in Geography". In Gaile, Gary Lee; Willmott, Cort James (eds.). Spatial Statistics and Models. Dordrecht: D. Reidel. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-94-017-3048-8. OCLC 883391388. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Kendall, Sir Maurice George; Stuart, Alan (1967). "Inference and Relationship". The Advanced Theory of Statistics. 2 (2nd ed.). New York: Hafner Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-02-847640-7. OCLC 423859.

- Diewert, Walter Erwin; Fox, Kevin John (1 July 2008). "On the estimation of returns to scale, technical progress and monopolistic markups". Journal of Econometrics. The use of econometrics in informing public policy makers. North Holland: Elsevier BV. 145 (1): 183–184. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2008.05.002. ISSN 0304-4076. Footnotes 34 and 37.

- Villegas, Cesáreo (December 1961). "Maximum Likelihood Estimation of a Linear Functional Relationship". Annals of Mathematical Statistics. Uruguay: Institute of Mathematical Statistics. 32 (4): 1048–1062. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177704845. ISSN 0003-4851.

- Lindley, Dennis Victor (1947). "Regression Lines and the Linear Functional Relationship". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Supplement Series B (Methodological). London. 9 (2): 218–244. doi:10.2307/2984115. ISSN 1466-6162. JSTOR 2984115.