Bhavacakra

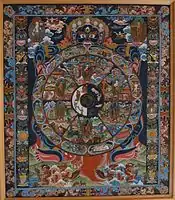

The bhāvacakra (Sanskrit; Pāli: bhāvacakka; Tibetan: srid pa'i 'khor lo) is a symbolic representation of saṃsāra (or cyclic existence). It is found on the outside walls of Tibetan Buddhist temples and monasteries in the Indo-Tibetan region, to help ordinary people understand Buddhist teachings. It is used in Indian Buddhism & Tibetian Buddhism

| Translations of bhāvacakra | |

|---|---|

| English | wheel of life, wheel of cyclic existence, etc. |

| Sanskrit | bhāvacakra (Dev: भवचक्र) |

| Pali | bhāvacakka (Dev: भवचक्क) |

| Chinese | 有輪 (Pinyin: yǒulún) |

| Tibetan | སྲིད་པའི་འཁོར་ལོ་ (Wylie: srid pa'i 'khor lo; THL: sipé khorlo) |

| Glossary of Buddhism | |

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Etymology

Bhāvachakra, "wheel of life,"[lower-alpha 1] consists of the words bhāva and cakra.

bhāva (भाव) means "being, worldly existence, becoming, birth, being, production, origin".[web 1]

The Sanskrit word bhāva (भाव) is rooted in the term bhava, and means "emotion, sentiment, state of body or mind, disposition."[web 2] In some contexts it also means "becoming, being, existing, occurring, appearance" while connoting the condition thereof.[web 3]

In Buddhism, bhava denotes the continuity of becoming (reincarnating) in one of the realms of existence, in the samsaric context of rebirth, life and the maturation arising therefrom.[2] It is the tenth of the Twelve Nidanas, in its Pratītyasamutpāda doctrine.[3]

The word Chakra (चक्र) derives from the Sanskrit word meaning "wheel," as well as "circle" and "cycle".[4]

The word chakra is used to mean several different things in the Sanskrit sources:[5]

- "Circle," used in a variety of senses, symbolising endless rotation of shakti.

- A circle of people. In rituals, there are different cakrasādhanās in which adherents assemble and perform rites. According to the Niruttaratantra, chakras in the sense of assemblies are of 5 types.

- The term chakra is also used to denote yantras (mystic diagrams), variously known as trikoṇa-cakra, aṣṭakoṇa-cakra, etc.

- Different nerve plexuses within the body.

Legend has it that the historical Buddha himself created the first depiction of the bhavacakra, and the story of how he gave the illustration to King Rudrāyaṇa appears in the anthology of Buddhist narratives called the Divyāvadāna.

Explanation of the diagram

The bhavachakra is painted on the outside walls of nearly every Tibetan Buddhist temple in Tibet and India, to instruct non-monastic audience about the Buddhist teachings.[6][7]

Elements of the bhavachakra

The bhavachakra consists of the following elements:

- The pig, rooster and snake in the hub of the wheel represent the three poisons of ignorance, attachment and aversion.

- The second layer represents karma.

- The third layer represents the six realms of samsara.

- The fourth layer represents the twelve links of dependent origination.

- The fierce figure holding the wheel represents impermanence. It is also Yama, the god of death.[8]

- The moon above the wheel represents liberation from samsara or cyclic existence.

- The Buddha pointing to the white circle indicates that liberation is possible.

Symbolically, the three inner circles, moving from the center outward, show that the three poisons of ignorance, attachment, and aversion give rise to positive and negative actions; these actions and their results are called karma. Karma in turn gives rise to the six realms, which represent the different types of suffering within samsara.

The fourth and outer layer of the wheel symbolizes the twelve links of dependent origination; these links indicate how the sources of suffering—the three poisons and karma—produce lives within cyclic existence.

The fierce being holding the wheel represents impermanence; this symbolizes that the entire process of samsara or cyclic existence is impermanent, transient, constantly changing. The moon above the wheel indicates liberation. The Buddha is pointing to the moon, indicating that liberation from samsara is possible.[9][10]

Hub: the three poisons

In the hub of the wheel are three animals: a pig, a snake, and a bird. They represent the three poisons of ignorance, aversion, and attachment, respectively. The pig stands for ignorance; this comparison is based on the Indian concept of a pig being the most foolish of animals, since it sleeps in the dirtiest places and eats whatever comes to its mouth. The snake represents aversion or anger; this is because it will be aroused and strike at the slightest touch. The bird represents attachment (also translated as desire or clinging). The particular bird used in this diagram represents an Indian bird that is very attached to its partner. These three animals represent the three poisons, which are the core of the bhavacakra. From these three poisons, the whole cycle of existence evolves.[11][12]

In many drawings of the wheel, the snake and bird are shown as coming out of the mouth of the pig, indicating that aversion and attachment arise from ignorance. The snake and bird are also shown grasping the tail of the pig, indicating that they in turn promote greater ignorance.[12]

Under the influence of the three poisons, beings create karma, as shown in the next layer of the circle.

Second layer: karma

The second layer of the wheel shows two-half circles:

- One half-circle (usually light) shows contented people moving upwards to higher states, possibly to the higher realms.

- The other half-circle (usually dark) shows people in a miserable state being led downwards to lower states, possibly to the lower realms.

These images represent karma, the law of cause and effect. The light half-circle indicates people experiencing the results of positive actions. The dark half-circle indicates people experiencing the results of negative actions.[12]

Ringu Tulku states:

- We create karma in three different ways, through actions that are positive, negative, or neutral. When we feel kindness and love and with this attitude do good things, which are beneficial to both ourselves and others, this is positive action. When we commit harmful deeds out of equally harmful intentions, this is negative action. Finally, when our motivation is indifferent and our deeds are neither harmful or beneficial, this is neutral action. The results we experience will accord with the quality of our actions.[13]

Propelled by their karma, beings take rebirth in the six realms of samsara, as shown in the next layer of the circle.

Third layer: the six realms of samsara

The third layer of the wheel is divided into six sections that represent the six realms of samsara, or cyclic existence, the process of cycling through one rebirth after another. These six realms are divided into three higher realms and three lower realms. The wheel can also be represented as having five realms, combining the God realm and the Demi-god realm into a single realm.

The three higher realms are shown in the top half of the circle:

- God realm (Deva): the gods lead long and enjoyable lives full of pleasure and abundance, but they spend their lives pursuing meaningless distractions and never think to practice the dharma. When death comes to them, they are completely unprepared; without realizing it, they have completely exhausted their good karma (which was the cause for being reborn in the god realm) and they suffer through being reborn in the lower realms.

- Demi-god realm (Asura): the demi-gods have pleasure and abundance almost as much as the gods, but they spend their time fighting among themselves or making war on the gods. When they make war on the gods, they always lose, since the gods are much more powerful. The demi-gods suffer from constant fighting and jealousy, and from being killed and wounded in their wars with each other and with the gods.

- Human realm (Manuṣya): humans suffer from hunger, thirst, heat, cold, separation from friends, being attacked by enemies, not getting what they want, and getting what they don't want. They also suffer from the general sufferings of birth, old age, sickness and death. Yet the human realm is considered to be the most suitable realm for practicing the dharma, because humans are not completely distracted by pleasure (like the gods or demi-gods) or by pain and suffering (like the beings in the lower realms).

The three lower realms are shown in the bottom half of the circle:

- Animal realm (Tiryagyoni): wild animals suffer from being attacked and eaten by other animals; they generally lead lives of constant fear. Domestic animals suffer from being exploited by humans; for example, they are slaughtered for food, overworked, and so on.

- Hungry ghost realm (Preta): hungry ghosts suffer from extreme hunger and thirst. They wander constantly in search of food and drink, only to be miserably frustrated any time they come close to actually getting what they want. For example, they see a stream of pure, clear water in the distance, but by the time they get there the stream has dried up. Hungry ghosts have huge bellies and long, thin necks. On the rare occasions that they do manage to find something to eat or drink, the food or water burns their neck as it goes down to their belly, causing them intense agony.

- Hell realm (Naraka): hell beings endure unimaginable suffering for eons of time. There are actually eighteen different types of hells, each inflicting a different kind of torment. In the hot hells, beings suffer from unbearable heat and continual torments of various kinds. In the cold hells, beings suffer from unbearable cold and other torments.[14][15][16][17][18][19]

Among the six realms, the human realm is considered to offer the best opportunity to practice the dharma.[17] In some representations of the wheel, there is a buddha or bodhisattva depicted within each realm, trying to help sentient beings find their way to nirvana.

Outer rim: the twelve links

The outer rim of the wheel is divided into twelve sections that represent the Twelve Nidānas. As previously stated, the three inner layers of the wheel show that the three poisons lead to karma, which leads to the suffering of the six realms. The twelve links of the outer rim show how this happens—by presenting the process of cause and effect in detail.[20][21]

These twelve links can be understood to operate on an outer or inner level.[22]

- On the outer level, the twelve links can be seen to operate over several lifetimes; in this case, these links show how our past lives influence our current lifetime, and how our actions in this lifetime influence our future lifetimes.[22]

- On the inner level, the twelve links can be understood to operate in every moment of existence in an interdependent manner.[23] On this level, the twelve links can be applied to show the effects of one particular action.[22]

By contemplating on the twelve links, one gains greater insight into the workings of karma; this insight enables us to begin to unravel our habitual way of thinking and reacting.[22][24][25]

The twelve causal links, paired with their corresponding symbols, are:

- Avidyā lack of knowledge – a blind person, often walking, or a person peering out

- Saṃskāra constructive volitional activity – a potter shaping a vessel or vessels

- Vijñāna consciousness – a man or a monkey grasping a fruit

- Nāmarūpa name and form (constituent elements of mental and physical existence) – two men afloat in a boat

- Ṣaḍāyatana six senses (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind) – a dwelling with six windows

- Sparśa contact – lovers consorting, kissing, or entwined

- Vedanā pain – an arrow to the eye

- Tṛṣṇa thirst – a drinker receiving drink

- Upādāna grasping – a man or a monkey picking fruit

- Bhava coming to be – a couple engaged in intercourse, a standing, leaping, or reflective person

- Jāti being born – woman giving birth

- Jarāmaraṇa old age and death – corpse being carried

The figure holding the wheel: impermanence

The wheel is being held by a fearsome figure who represents impermanence.[8]

This figure is often interpreted as being Mara, the demon who tried to tempt the Buddha, or as Yama, the lord of death.[26] Regardless of the figure depicted, the inner meaning remains the same–that the entire process of cyclic existence (samsara) is transient; everything within this wheel is constantly changing.[27]

Yama has the following attributes:

- He wears a crown of five skulls that symbolize the impermanence of the five aggregates.[28] (The skulls are also said to symbolize the five poisons.)

- He has a third eye that symbolizes the wisdom of understanding impermanence.[28]

- He is sometimes shown adorned with a tiger skin, which symbolizes fearfulness.[28] (The tiger skin is typically seen hanging beneath the wheel.)

- His four limbs (that are clutching the wheel) symbolize the sufferings of birth, old age, sickness, and death.[29]

The moon: liberation

Above the wheel is an image of the moon; the moon represents liberation from the sufferings of samsara.[21][30][31] Some drawings may show an image of a "pure land" to indicate liberation, rather than a moon.

The Buddha pointing to the white circle: the path to liberation

The upper part of the drawing also shows an image of the Buddha pointing toward the moon; this represents the path to liberation.[21][30][31] While in Theravada Buddhism this is the Noble Eightfold Path, in Mahayana Buddhism this is the Bodhisattva path, striving to liberation for all sentient beings. In Tibetan Buddhism, this is Lamrim, which details all the stages on the path, while Zen has its own complicated history of the entanglement of meditation practice and direct insight.

Inscription

Drawings of the Bhavacakra usually contain an inscription consisting of a few lines of text that explain the process that keeps us in samara and how to reverse that process.[21]

Alternative interpretations

Theravada

The Theravada-tradition does not have a graphical representation of the round of rebirths, but cakra-symbolism is an elementary component of Buddhism, and Buddhaghosa's Path of Purification (Visuddhimagga) contains such imagery:

It is the beginningless round of rebirths that is called the 'Wheel of the round of rebirths' (saṃsāracakka). Ignorance (avijjā) is its hub (or nave) because it is its root. Ageing-and-death (jarā-maraṇa) is its rim (or felly) because it terminates it. The remaining ten links (of the Dependent Origination) are its spokes (i.e. karma formations [saṅkhāra] up to process of becoming [bhava]).[32]

Western psychological interpretation

Some western interpreters take a psychological point of view, explaining that different karmic actions contribute to one's metaphorical existence in different realms, or rather, different actions reinforce personal characteristics described by the realms. According to Mark Epstein, "each realm becomes not so much a specific place but rather a metaphor for a different psychological state, with the entire wheel becoming a representation of neurotic suffering."[33]

Gallery

A painting of the bhavacakra from Bhutan.

A painting of the bhavacakra from Bhutan. A painting of the bhavacakra that depicts an emanation of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in each realm.

A painting of the bhavacakra that depicts an emanation of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in each realm. A painting of the bhavacakra in Thikse Monastery, Ladakh.

A painting of the bhavacakra in Thikse Monastery, Ladakh. A traditional Tibetan thangka showing the bhavacakra. This thangka was made in Eastern Tibet and is currently housed in the Birmingham Museum of Art.

A traditional Tibetan thangka showing the bhavacakra. This thangka was made in Eastern Tibet and is currently housed in the Birmingham Museum of Art.

See also

- Buddhism and psychology

- Buddhist cosmology – Description of the universe in Buddhist texts

- Buddhist symbolism

- Dependent origination

- Dharmachakra – A symbol of Indian religions

- Gankyil

- Karma in Buddhism – Action driven by intention which leads to future consequences

- Kleshas (Buddhism) – In Buddhism, mental states that cloud the mind

- Rota Fortunae – Symbol of fate in medieval and ancient philosophy

- The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things, by Hieronymus Bosch

- Three poisons

References

Footnotes

- The term bhavachakra has been translated into English as:

- Wheel of becoming[1]

- Wheel of cyclic existence

- Wheel of existence

- Wheel of life

- Wheel of rebirth

- Wheel of saṃsāra

- Wheel of suffering

- Wheel of transformation

Citations

- Gethin 1998, pp. 158-159.

- Thomas William Rhys Davids; William Stede (1921). Pali-English Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 499. ISBN 978-81-208-1144-7.

- Julius Evola; H. E. Musson (1996). The Doctrine of Awakening: The Attainment of Self-Mastery According to the Earliest Buddhist Texts. Inner Traditions. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-89281-553-1.

- Mallory, J.P; Adams, D.Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture (1. publ. ed.). London: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 640. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- Bhattacharyya, N. N. (1999). History of the Tantric Religion (Second Revised ed.). New Delhi: Manohar. pp. 385–86. ISBN 81-7304-025-7.

- Dzongsar Khyentse (2004), p. 3.

- Dalai Lama (1992), p. 1

- Dalai Lama (1992), p. 42–43.

- Dalai Lama (1992), p. 41-43.

- Sonam Rinchen (2006), p. 8-9.

- Ringu Tulku (2005), p. 30.

- Dalai Lama (1992), p. 4, 42.

- Ringu Tulku (2005), p. 31.

- Khandro Rinpoche (2003), p. 65-90.

- Chögyam Trungpa (1999), p. 25-50.

- Dalai Lama (1992), p. 5-8.

- Dzongsar Khyentse (2005), p. 2-3.

- Patrul Rinpoche (1998), p. 61-99.

- Gampopa (1998), p. 95-108

- Dalai Lama (1992), p. 8 (from the Introduction by Jeffrey Hopkins)

- Sonam Rinchen (2006), p. 9.

- Thrangu Rinpoche (2001), pp. 3, 32

- Simmer-Brown (1987), p. 24

- Goodman, Location 1492 (Kindel edition)

- Simmer-Brown (1987), p. 28

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 112.

- Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art: Guide to the Collection. London, UK: GILES. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5. Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- Khantipalo (1995-2011)

- Thubten Chodron (1993), Part 1 of 5, p. 1

- Dalai Lama (1992), p. 43.

- Thubten Chodron (1993), Part 2 of 5, p. 5

- Karunaratne, T. B. (2008), p. 14.

- Epstein, Mark (2004), p. 17.

Sources

Buddhist sources

- Bhikkhu Khantipalo (1995-2011). The Wheel of Birth and Death. Access to Insight.

- Chögyam Trungpa (1999). The Myth of Freedom and the Way of Meditation. Shambhala

- Chögyam Trungpa (2000). The Tibetan Book of the Dead: The Great Liberation through Hearing in the Bardo. Shambhala

- Chögyam Trungpa (2009). The Truth of Suffering and the Path of Liberation. Shambhala

- Dalai Lama (1992). The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins. Wisdom.

- Dzongsar Khyentse (2004). Gentle Voice #22, September 2004 Issue.

- Dzongsar Khyentse (2005). Gentle Voice #23, April 2005 Issue.

- Epstein, Mark (2004). Thoughts Without A Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective. Basic Books. Kindle Edition.

- Gampopa (1998). The Jewel Ornament of Liberation: The Wish-Fulfilling Gem of the Noble Teachings, by Gampopa, translated by Khenpo Konchog Gyaltsen Rinpoche. Snow Lion.

- Goodman, Steven D. (1992). "Situational Patterning: Pratītyasamutpāda." Footsteps on the Diamond Path, Crystal Mirror Series I-III. Dharma Publishing.

- Geshe Sonam Rinchen (2006). How Karma Works: The Twelve Links of Dependent Arising. Snow Lion

- Karunaratne, T. B. (2008). The Buddhist Wheel Symbol. Buddhist Publication Society. (http://www.bps.lk/olib/wh/wh137.pdf)

- Khandro Rinpoche (2003). This Precious Life. Shambala

- Patrul Rinpoche (1998). The Words of My Perfect Teacher, translated by the Padmakara Translation Group. Altamira.

- Ringu Tulku (2005). Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism. Snow Lion.

- Simmer-Brown, Judith (1987). "Seeing the Dependent Origination of Suffering as the Key to Liberation." Journal of Contemplative Psychotherapy, VOLUME IV. The Naropa Institute. (ISSN 0894-8577)

- Thrangu Rinpoche (2001). The Twelve Links of Interdependent Origination. Nama Buddha Publications.

- Thubten Chodron. Articles & Transcripts of Teachings on Lamrim: The Gradual Path to Enlightenment. Dharma Friendship Foundation.

- Thubten Chodron (1993). The Twelve Links – Part 1 of 5 (PDF)

- Thubten Chodron (1993). The Twelve Links – Part 2 of 5 (PDF)

Scholarly sources

- Buswell, Robert E., Jr.; Lopez, Donald S., Jr., eds. (2013), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University Press

- Donath, Dorothy C. (1971), Buddhism for the West: Theravāda, Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna; a comprehensive review of Buddhist history, philosophy, and teachings from the time of the Buddha to the present day, Julian Press, ISBN 0-07-017533-0

- Gethin, Rupert (1998), Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-289223-1

- Teiser, Stephen (2007). Reinventing the Wheel: Paintings of Rebirth in Medieval Buddhist Temples. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295986494.

Web-sources

- Monier Monier-Williams (1899), Sanskrit English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Archive: भव, bhava

- भव Archived 2017-07-07 at the Wayback Machine, Sanskrit English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- Monier Monier-Williams (1899), Sanskrit English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Archive: भाव, bhAva

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bhavacakra. |

- Interactive Tour of the Wheel of Life, buddhanet.net

- Wheel of Life index page, Himalayan Art Resources – allows visitors to view a gallery of images from various public and private collections

- Wheel of Life Thangka painting explained

- The Wheel of Birth and Death by Bhikkhu Khantipalo, The Wheel Publication No. 147/148/149, Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society 1970

- The Wheel of Suffering, quietmountain.org – brief description focusing on the six realms

- Wheel of Life on Khandro.net