Buddhism in the Philippines

Buddhism is a minor religion in the Philippines.[1] The Buddhist population of the Philippines is 46,558 according to the 2010 Census.[2][3]

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

History

No written records of early Buddhism in the Philippines exist. Recent archaeological discoveries and the few scant references in the other nations's historical records indicate, however, the presence of Buddhism from the 9th century onward in the islands. These records mention the independent states that comprised the Philippines, and show that they were not united as one country in the early days.

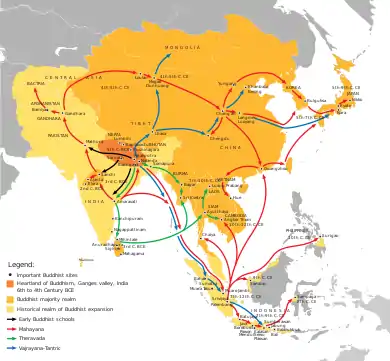

Vajrayāna in the Philippines was also linked through the maritime trade routes with its counterparts in India, Sri Lanka, Champa, Cambodia, China and Japan, to the extent that it is hard to separate them completely and it is better to speak of a complex of esoteric Buddhism in medieval Maritime Asia. In many of the key South Asian port cities that saw the growth of Esoteric Buddhism, the tradition coexisted alongside Shaivism.[4]

Both the Śrīvijayan empire in Sumatra and the Majapahit empire in Java were unknown in Western history until 1918 when George Coedes of the Ecole Francaise d’Extreme Orient postulated their existence because they had been mentioned in the records of the Chinese Tang and Sung imperial dynasties. Yi Jing, a Chinese monk and scholar, stayed in Sumatra from 687 to 689 on his way to India. He wrote on the Srivijaya's splendour, "Buddhism was flourishing throughout the islands of Southeast Asia. Many of the kings and the chieftains in the islands in the southern seas admire and believe in Buddhism, and their hearts are set on accumulating good action." The Srivijaya empire flourished as a Buddhist cultural centre over 600 years from 650 to 1377 in Palembang, Sumatra. Built as a mandala on a hill from 770 to 825 in central Java, the Borobodur stands today as the living testament of the Srivijaya empire's grandeur. Three generations of the Sailendra kings built the temple that displays a three-dimensional view of the Vajrayāna Buddhist cosmology. Later on, the Javanese Majapahit empire took control over the Srivijaya and became the leading Buddhist cultural centre from 1292 to 1478 in Southeast Asia. Both empires supplemented their otherwise austere practice of Theravāda with the rituals of Vajrayāna in the 7th century.[5]

In an of itself not a school of Buddhism, Vajrayāna, literally "adamantine" or "diamond vehicle" and also known as Tantric or Mantrayāna Buddhism, is instead practised as a tradition on top of Theravāda or Mahāyāna Buddhism. Ritual practice rather than meditation is the distinguishing mark of Vajrayāna. In addition, its esoteric teachings may only be conveyed through dharma transmission.

Archaeological findings

The Philippines's archaeological finds include a few Buddhist artifacts,[6][7] The style exhibits Vajrayāna influence,[8][9][10][5] most of them dated to the 9th century. The artifacts reflect the iconography of the Śrīvijayan empire's Vajrayāna and its influences on the Philippines's early states. The artifacts's distinct features point to their production in the islands and they hint at the artisan's or goldsmith's knowledge of Buddhist culture and literature because the artisans have made these unique works of Buddhist art. The artifacts imply also the presence of Buddhist believers in the places where these artifacts turned up. These places extended from the Agusan-Surigao area in Mindanao island to Cebu, Palawan, and Luzon islands. Hence, Vajrayāna ritualism must have spread far and wide throughout the archipelago.

In 1225, China's Zhao Rugua, a superintendent of maritime trade in Fukien province wrote the book entitled Zhu Fan Zhi (Chinese: 諸番志; lit. '"Account of the Various Barbarians"') in which he described trade with a country called Ma-i in the island of Mindoro in Luzon,(pronounced "Ma-yi") which was a prehispanic Philippine state. In it he said:

The country of Mai is to the north of Borneo. The natives live in large villages on the opposite banks of a stream and cover themselves with a cloth like a sheet or hide their bodies with a loin cloth. There are metal images of Buddhas of unknown origin scattered about in the tangled wilds.[11]

"The gentleness of Tagalog customs that the first Spaniards found, very different from those of other provinces of the same race and in Luzon itself, can very well be the effect of Buddhism "There are copper Buddha's" images.[12]

The gold statue of the deity Tara is the most significant Buddhist artifact. In the Vajrayāna tradition, Tara symbolizes the Absolute in its emptiness as the wisdom heart's essence that finds its expression through love and through compassion. The Vajrayāna tradition also tells about the outpouring of the human heart's compassion that manifests Tara and about the fascinating story of the Bodhisattva of Compassion shedding a tear out of pity for the suffering of all sentient beings when he hears their cries. The tear created a lake where a lotus flower emerges. It bears Tara who relieves their sorrow and their pain.

The Golden Tara was discovered in 1918 in Esperanza, Agusan and it has been kept in the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois since the 1920s. Henry Otley Beyer, the Philippines's pioneer anthropologist-archaeologist, and some experts have agreed on its identity and have dated it to belong within 900–950 CE, which covers the Sailendra period of the Srivijaya empire. They can not place, however, the Golden Tara's provenance because it has distinct features.

In the archipelago that was to become the Philippines, the statues of the Hindu gods were hidden to prevent their destruction by a religion which destroyed all cult images. One statue, a "Golden Tara", a 4-pound gold statue of a Hindu-Malayan goddess, was found in Mindanao in 1917. The statue denoted the Agusan Image and is now in the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. The image is that of a Hindu-Malayan female deity, seated cross-legged. It is made of twenty-one carat gold and weighs nearly four pounds. It has a richly ornamented headdress and many ornaments in the arms and other parts of the body. Scholars date it to the late 13th or early 14th century. It was made by local artists, perhaps copying from an imported Javanese model. The gold that was used was from this area, since Javanese miners were known to have been engaged in gold mining in Butuan at this time. The existence of these gold mines, this artifact and the presence of "foreigners" proves the existence of some foreign trade, gold as the main element in the barter economy, and of cultural and social contact between the natives and "foreigners."

As previously stated, this statue is not in the Philippines. Louise Adriana Wood (whose husband, Leonard Wood, was the military-governor of the Moro Province in 1903-1906 and governor general in 1921-1927) raised funds for its purchase by the Chicago Museum of Natural History. It is now on display in that museum's Gold Room. According to Prof. Beyer, considered the "Father of Philippine Anthropology and Archeology", a woman in 1917 found it on the left bank of the Wawa River near Esperanza, Agusan, projecting from the silt in a ravine after a storm and flood. From her hands it passed into those of Bias Baklagon, a local government official. Shortly after, ownership passed to the Agusan Coconut Company, to whom Baklagon owed a considerable debt. Mrs. Wood bought it from the coconut company.

A golden statuette of the Hindu-Buddhist goddess Kinnara found in an archeological dig in Esperanza, Agusan del Sur.

The Philippines's archaeological finds include many ancient gold artifacts. Most of them have been dated to belong to the 9th century iconography of the Srivijaya empire. The artifacts' distinct features point to their production in the islands. It is probable that they were made locally because archaeologist Peter Bellwood discovered the existence of an ancient goldsmith's shop that made the 20-centuries-old lingling-o, or omega-shaped gold ornaments in Batanes.[13] Archaeological finds include Buddhist artifacts.[6][7] The style are of Vajrayāna influence.[8][14]

The other finds are the garuda, the mythical bird that has been common to Buddhism and Hinduism, and several Padmapani images. Padmapani has been also known as Avalokitesvara, the enlightened being or Bodhisattva of Compassion.[15]

Surviving Buddhist images and sculptures are primarily found in and at Tabon Cave.[14] Recent research conducted by Philip Maise has included the discovery of giant sculptures, has also discovered what he believes to be cave paintings within the burial chambers in the caves depicting the Journey to the West.[16] Scholars such as Milton Osborne emphasize that despite these beliefs being originally from India, they reached the Philippines through Southeast Asian cultures with Austronesian roots.[17] Artifacts reflect the iconography of the Vajrayāna tradition and its influences on the Philippines's early states.[18]

- Bronze Lokesvara – This is bronze statue of Lokesvara was found in Isla Puting Bato in Tondo, Manila.[19]

- Buddha Amithaba bass relief - The Ancient Batangueños were influenced by India as shown in the origin of most languages from Sanskrit and certain ancient potteries. A Buddhist image was reproduced in mould on a clay medallion in bas-relief from the municipality of Calatagan. According to experts, the image in the pot strongly resembles the iconographic portrayal of Buddha in Siam, India, and Nepal. The pot shows Buddha Amithaba in the tribhanga pose inside an oval nimbus. Scholars also noted that there is a strong Mahayanic orientation in the image, since the Boddhisattva Avalokitesvara was also depicted.[20]

- Golden Garuda of Palawan - Another gold artifact, from the Tabon Caves in the island of Palawan, is an image of Garuda, the bird who is the mount of Vishnu. The discovery of sophisticated Hindu imagery and gold artifacts in Tabon Caves has been linked to those found from Oc Eo, in the Mekong Delta in Southern Vietnam.

- Bronze Ganesha statues – A crude bronze statue of a Hindu Deity Ganesha has been found by Henry Otley Beyer in 1921 in an ancient site in Puerto Princesa, Palawan and in Mactan. Cebu the crude bronze statue indicates of its local reproduction.[19]

- Mactan Alokitesvara – Excavated in 1921 in Mactan, Cebu by H.O.Beyer the statue is bronze may be a siva-buddhist blending rather than "pure Buddhist".[19]

- The Golden Tara[21][22]

- Golden Kinnari

- Padmapani and Nandi images – Padmapani is also known as Avalokitesvara, the wisdom being or Bodhisattva of Compassion. Golden jewelry found so far include rings, some surmounted by images of Nandi – the sacred bull, linked chains, inscribed gold sheets, gold plaques decorated with repoussé images of Hindu deities.[23][24]

- The Laguna Copperplate Inscription (above) found in 1989 suggests Indian cultural influence in the Philippines by 9th century AD, likely through Hinduism in Indonesia, prior to the arrival of European colonial empires in the 16th century.

Batangas

The ancient Batangueños were influenced by India, as shown in the origin of most languages from Sanskrit and certain ancient potteries. A Buddhist image was reproduced in mould on a clay medallion in bas-relief from the municipality of Calatagan.

According to experts, the image in the pot strongly resembles the iconographic portrayal of Buddha in Siam, India, and Nepal. The pot shows Buddha Amithaba in the tribhanga[25] pose inside an oval nimbus. Scholars also noted that there is a strong Mahayanic orientation in the image since the Boddhisattva Avalokitesvara was also depicted.[26]

Batanes

Archaeologist Peter Bellwood discovered the existence of an ancient goldsmith's shop that made the 20-centuries-old ngling-o, or omega-shaped gold ornaments in Batanes.[27] Archaeological finds include Buddhist artifacts.[28][29]

Butuan

Evidence indicates that Butuan was in contact with the Song dynasty of China by at least 1001 AD. The Chinese annal Song Shih recorded the first appearance of a Butuan tributary mission (Li Yui-han 李竾罕 and Jiaminan) at the Chinese Imperial Court on March 17, 1001 AD and it described Butuan (P'u-tuan) as a small Hindu country with a Buddhist monarchy in the sea that had a regular connection with the Champa kingdom and intermittent contact with China under the Rajah named Kiling.[30] The rajah sent an envoy under I-hsu-han, with a formal memorial requesting equal status in court protocol with the Champa envoy. The request was denied later by the Imperial court, mainly because of favoritism over Champa.[31]

A golden statuette of the Hindu-Buddhist goddesses Tara in Agusan river and the Kinnara was found in an archaeological dig in Esperanza, Agusan del Sur. The Philippines's archaeological finds include many ancient gold artifacts. It is probable that they were made locally because archaeologist Peter Bellwood discovered the existence of an ancient goldsmith's shop.[27] Archaeological finds also include Buddhist artifacts.[28][29]

Mindoro

In 1225, China's Zhao Rugua, a superintendent of maritime trade in Fukien province, wrote the book titled Account of the Various Barbarians (Chinese: 諸番志) in which he described trade with a country called Ma-i in the island of Mindoro in Luzon, (pronounced "Ma-yi") which was a pre-Hispanic Philippine state. The book describes the presence of metal images of Buddhas of unknown origin scattered about in the tangled wilds. The gentleness of Tagalog customs that the first Spaniards found, were very different from those of other provinces of the same race and in Luzon itself, can very well be the effect of Buddhism.[32][33]

Palawan

In the 13th century, Buddhism and Hinduism was introduced to the people of Palawan through the Srivijaya and Majapahit .[14] The other finds are the garuda, the mythical bird that has been common to Buddhism and Hinduism, and several Padmapani images. Padmapani has been also known as Avalokitesvara, the enlightened being or Bodhisattva of Compassion. Surviving Buddhist images and sculptures are primarily found in and at Tabon Cave.[34] Recent research conducted by Philip Maise has included the discovery of giant sculptures and cave paintings within the burial chambers in the caves depicting the Journey to the West.[35]

Tondo

A relic of a bronze statue of Lokesvara was found in Isla Puting Bato in Tondo, Manila.[19] and the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, which is the artifact that specifically points to an Indian cultural (linguistic) influence in Tondo, does not explicitly discuss religious practices. However, some contemporary Buddhist practitioners believe that its mention of the Hindu calendar month of Vaisakha (which corresponds to April/May in the Gregorian Calendar) implies a familiarity with the Hindu sacred days celebrated during that month.[36]

Present day

Both extant schools of Buddhism are present in the Philippines.[37] There are Mahāyāna monasteries, temples, lay organizations, meditation centers and groups, such as Fo Guang Shan, Soka Gakkai International which is an international Nichiren Buddhist organization founded in Japan.[38] The Maha Bodhi Society's Zen circle was founded in October 1998.[39] Fo Guang Shan Manila is the main branch of the Fo Guang Shan Buddhist Order in the Philippines which has several temples across the country.[40]

Despite being located in Southeast Asia, the Theravāda school has but a marginal presence. The Philippine Theravāda Buddhist Fellowship regularly holds fellowship meetings and promotes Theravāda Buddhism in the country. There also exists a nonsectarian S. N. Goenka vipassanā meditation centre in Quezon.

Incorporation into folk religion

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

The Tagalog and Visayan belief system was more or less anchored on the idea that the world is inhabited by spirits and supernatural entities, both good and bad, and that respect must be accorded to them through worship.[41] The elements of Buddhist and Hindu beliefs has been syncretistically adapted or incorporated in the indigenous folk religions.[42] In the Philippine mythology, a diwata (derived from Sanskrit devata देवता;[43] encantada in Spanish) is a type of deity or spirit. The term "diwata" has taken on levels of meaning since its assimilation into the mythology of the pre-colonial Filipinos. The term is traditionally used in the Visayas, Palawan, and Mindanao regions, while the term anito is used in parts of Luzon region. Both terms are used in Bicol, Marinduque, Romblon, and Mindoro, signifying a 'buffer zone' area for the two terms. while the spelling of the name "Bathala" given by Pedro Chirino in "Relación de las Islas Filipinas" (1595–1602) was perhaps a combination of two different spellings of the name from older documents such as "Badhala" in "Relacion de las Costumbres de Los Tagalos" (1589, Juan de Plasencia) and "Batala" in "Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas" (1582, Miguel de Loarca), the latter was supposedly the correct spelling in Tagalog since the letter "h" was silent in Spanish. Bathala or Batala was apparently derived from Sanskrit "bhattara" (noble lord) which appeared as the sixteenth-century title "batara" in the southern Philippines and Borneo. In Indonesian language, "batara" means "god", its feminine counterpart was "batari". It may be worth noting that in Malay, "betara" means holy, and was applied to the greater Hindu gods in Java, and was also assumed by the ruler of Majapahit.

Influence on Philippine languages

Sanskrit and, to a lesser extent, Pāli have left lasting marks on the vocabulary of almost every indigenous language of the Philippines.[44][45][46]

On Pampangan

- kalma "fate" from Sanskrit karma

- damla "divine law" from Sanskrit dharma

- mantala "magic formulas" from Sanskrit mantra

- upaia "power" from Sanskrit or Pāli upāya

- lupa "face" from Sanskrit rūpa

- sabla "every" from Sanskrit sarva

- lau "eclipse" from Sanskrit rāhu

- galura "giant eagle (a surname)" from Sanskrit Garuḍa

- laksina "south (a surname)" from Sanskrit dakṣiṇa

- laksamana "admiral (a surname)" from Sanskrit lakṣmaṇa

On Tagalog

- budhi "conscience" from Sanskrit bodhi

- dalita from Sanskrit dalita

- diwa "Spirit; Soul" from Sanskrit jīva

- dukha "one who suffers" from Pāli dukkha

- diwata "deity, nymph" from Pāli deva

- guro "teacher" from Sanskrit guru

- sampalataya "faith" from Sanskrit sampratyaya

- mukha "face" from Pāli mukha

- laho "eclipse" from Sanskrit rāhu

- tala "star" from Sanskrit tārā

See also

References

- Hessler, Z. (2020, November 25). Burmese Theravada in a Catholic land (25) [Audio podcast episode]. In Insight Myanmar. https://www.insightmyanmar.org/complete-shows/2020/11/28/episode-25-burmese-theravada-in-a-catholic-land-part-1

- "Buddhism in Philippines, Guide to Philippines Buddhism, Introduction to Philippines Buddhism, Philippines Buddhism Travel". Archived from the original on August 20, 2007.

- "Religions in Philippines | PEW-GRF". www.globalreligiousfutures.org.

- Acri, Andrea. Esoteric Buddhism in Mediaeval Maritime Asia: Networks of Masters, Texts, Icons, page 10.

- filipinobuddhism (November 8, 2014). "Early Buddhism in the Philippines".

- Jesus Peralta, "Prehistoric Gold Ornaments CB Philippines," Arts of Asia, 1981, 4:54–60

- Art Exhibit: Philippines' 'Gold of Ancestors' in Newsweek.

- Laszlo Legeza, "Tantric Elements in Pre-Hispanic Gold Art," Arts of Asia, 1988, 4:129–133.

- "Camperspoint: History of Palawan". Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Accessed 27 August 2008.

- Prehispanic Source Materials: for the study of Philippine History" (Published by New Day Publishers, Copyright 1984) Written by William Henry Scott, Page 68.

- Rizal, Jose (2000). Political and Historical Writings (Vol. 7). Manila: National Historical Institute.

- Khatnani, Sunita (October 11, 2009). "The Indian in the Filipino". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- Camperspoint: History of Palawan Archived 2009-01-15 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed August 27, 2008.

- "Early Buddhism in the Philippines". November 8, 2014.

- "'Great Sphinx' Found in Tabon Caves in Palawan". MetroCebu. August 12, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- Osborne, Milton (2004). Southeast Asia: An Introductory History (Ninth ed.). Australia: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-448-5.

- Laszlo Legeza, "Tantric Elements in the Philippines PreHispanic Gold Arts," Arts of Asia, 1988, 4:129–136.

- http://www.asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-15-1977/francisco-indian-prespanish-philippines.pdf

- http://asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-01-01-1963/Francisco%20Buddhist.pdf

- Agusan Gold Image only in the Philippines Archived 2012-06-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- Agusan Image Documents, Agusan-Surigao Historical Archives.

- Anna T. N. Bennett (2009), Gold in early Southeast Asia, ArcheoSciences, Volume 33, pp 99–107

- Dang V.T. and Vu, Q.H., 1977. The excavation at Giong Ca Vo site. Journal of Southeast Asian Archaeology 17: 30–37

- "tribhanga". Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved January 6, 2007.

- http://asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-01-01-1963/Francisco%20Buddhist.pdf

- Khatnani, Sunita (October 11, 2009). "The Indian in the Filipino". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- Jesus Peralta, "Prehistoric Gold Ornaments CB Philippines," Arts of Asia, 1981, 4:54–60

- Art Exhibit: Philippines' 'Gold of Ancestors' in Newsweek.

- "Timeline of history". Archived from the original on November 23, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- Scott, William Prehispanic Source Materials: For the Study of Philippine History, p. 66

- Prehispanic Source Materials: for the study of Philippine History" (Published by New Day Publishers, Copyright 1984) Written by William Henry Scott, Page 68.

- Rizal, Jose (2000). Political and Historical Writings (Vol. 7). Manila: National Historical Institute.

- Camperspoint: History of Palawan Archived 2009-01-15 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed August 27, 2008.

- "'Great Sphinx' Found in Tabon Caves in Palawan". MetroCebu. August 12, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- "Early Buddhism in the Philippines". Buddhism in the Philippines. Binondo, Manila: Philippine Theravada Buddhist Fellowship. November 9, 2014. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- Hessler, Z. (2020, December 26). Burmese Theravada in a Catholic land (28) [Audio podcast episode]. In Insight Myanmar. https://www.insightmyanmar.org/complete-shows/2020/12/25/episode-28-voices-burmese-theravada-in-a-catholic-land-part-2

- "Directory of Buddhist Organizations and Temples in the Philippines". Sangha Pinoy. Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- The Dharma Wheel, 1:1, 1998 Philippines Centennial Issue

- History of Fo Guang Shan in the Philippines

- Philippine Folklore Stories by John Maurice Miller

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- https://www.filipiknow.net/the-ancient-visayan-deities-of-philippine-mythology/

- Haspelmath, Martin. Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. De Gruyter Mouton. p. 724. ISBN 3110218437.

- Virgilio S. Almario, UP Diksunaryong Filipino

- Khatnani, Sunita (October 11, 2009). "The Indian in the Filipino". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

Sources

- Almario, Virgilio S. ed., : UP Diksiyonaryong Filipino. Pasig City: 2001.

- Concepcion, Samnak P.J., Quest of Zen: Awakening the Wisdom Heart. Bloomington, IN: Xlibris, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4535-6367-0

- Legeza, Laszlo, "Tantric Elements in Pre-Hispanic Philippines Gold Art," Arts of Asia, July–August 1988, pp. 129–136.

- Munoz, Paul Michel, Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and Malay Peninsula. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet: 2006. ISBN 981-4155-67-5

- Peralta, Jesus, "Prehistoric Gold Ornaments CB Philippines," Arts of Asia, 1981, 4:54–60.

- Religious Demographic Profile, The PEW Forum on Religion and Public Life. Retrieved 2008.

- Scott, William Henry, Prehispanic Source Material for the Study of Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 1984. ISBN 971-10-0226-4

- Thomas, Edward J., The Life of the Buddha: As Legend and History. India: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2003.

External links

Theravāda

- Dhammaphala, Goenka meditation centre

- Philippine Inisght-Meditation Community

Mahāyāna

- Mabuhay Temple, Fóguāngshān temple

- Ocean Sky Chán Monastery

- Tzu Chi Philippines

- Palyul Tibetan Buddhist Temple