Bhojshala

The Bhojshala (IAST: Bhojaśālā, sometimes Bhoj Shala, meaning 'Hall of Bhoja') is an historic building located in Dhar, Madhya Pradesh, India. The name is derived from the celebrated king Bhoja of the Paramāra dynasty of central India, a patron of education and the arts, to whom major Sanskrit works on poetics, yoga and architecture are attributed.[1] The term Bhojashala became linked to the building in the early 20th century; the architectural parts of the structure itself date mainly to the 12th century, with the Islamic tombs in the campus added between the 14th and 15th century.[1]

Bhojshala is presently an archaeological site under the protection of the Archaeological Survey of India, but over the last century it has become a site disputed between Hindus and Muslims. The exploration of the location since the 19th century has yielded information on medieval religions particularly of Hinduism and Jainism. The general precinct around the Bhojshala is also the location of four Sufi tombs.[2] The hypostyle hall was built primarily from temple pillars and parts around 1390 CE, while the original tomb of Kamal al-Din Malawi (c. 1238-1330) is older.[3] The Muslims use the building for Friday prayers and Islamic festivals, while the Hindus pray on Tuesday. The Hindus also seek to pray to goddess Sarasvatī at the site on Vasant Panchami festival, and this been a source of Hindu-Muslim tension when Vasant Panchami falls on a Friday.[4][5][6]

History: King Bhoja

King Bhoja, who ruled between circa 1000 and 1055 in central India, is considered an exceptional king in the Indian tradition.[7] He was a celebrated patron of arts, and out of reverence for him, Hindu scholars that followed traditionally attributed a large number of Sanskrit works on philosophy, astronomy, grammar medicine, yoga, architecture and other subjects to him. Of these, a well studied and influential text in the field of poetics is Śṛṅgaraprakāśa.[7][8] The core premise of the work is that Sringara is the fundamental and motivating impulse in the universe.

Along with his literary and art support, Bhoja began constructing a Shiva temple at Bhojpur. If it had been completed to the extent he planned, the temple would have been double the size of the Hindu temples at the Khajuraho Group of Monuments. The temple was partially completed, and the epigraphical evidence confirms that Bhoja founded and built Hindu temples.[7]

One of Bhoja's successors was king Arjunavarman (circa 1210-15). He and many others, in Hindu and Jain traditions, held Bhoja in such high regard that they stated or were revered as a reincarnation (rebirth) of Bhoja or Bhoja-like ruler.[7][9] Centuries later, Bhoja remained a revered figure as evidenced by Merutuṅga's Prabandhacintāmaṇi completed in the fourteenth century,[10] and Ballāla's Bhojaprabandha composed at Varanasi in the 17th century.[11] This tradition continued, and in the 20th century, Hindu scholars described Bhoja as an example of the glorious past of their historic culture and a part of Hindu identity.[7][12] The capital of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, Bhopal, is named after him, i.e. Bhoj-pāl but some trace the name to Bhūpāla, a Sanskrit word meaning king, literally, 'Protector of the Earth.' [13]

Dhār and Inscriptions in the Bhojaśālā

The archaeological sites at Dhār, especially the inscriptions, attracted the early attention of colonial Indologists and historians. John Malcolm mentioned Dhār in 1822, along with building projects such as the dams planned and completed by King Bhoja.[14] The scholarly study on the inscriptions of Bhojśālā continued in the late nineteenth century with the efforts of Bhau Daji in 1871.[14] A fresh page was turned in 1903 when K. K. Lele, Superintendent of Education in the Princely State of Dhār, reported a number of Sanskrit and Prakrit inscriptions in the walls and floor of the pillared hall at Kamāl Maula.[15] Study of the inscriptions has been continued by various scholars to the present. The variety and size of the inscribed tablets at the site, among them two serpentine inscriptions giving grammatical rules of the Sanskrit language, show that materials were brought from a wide area and a number of different structures.

Rāüla vela of Roḍa

John Malcolm mentioned that he removed an inscribed panel from the Kamāl Maula. [16] This appears to be the Rāüla vela of Roḍa, a unique poetic work in the earliest forms of Hindi. This inscription was kept first in The Asiatic Society of Mumbai and was later transferred to the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai.[17]

The Kūrmaśataka

Among the inscriptions found by K. K. Lele was a tablet with a series of verses in Prakrit praising the Kūrma or Tortoise incarnation of the god Viṣṇu. The Kūrmaśataka is attributed to king Bhoja but the palaeography of the record itself suggests that this copy was engraved in the twelfth or thirteenth century. The text was published by Richard Pischel in 1905–06, with a new version and translation appearing in 2003 by V. M. Kularni.[18] The inscription is currently on display inside the building.

The Vijayaśrīnāṭikā

Another inscription found by K. K. Lele is part of a drama called Vijayaśrīnāṭikā composed by Madana. The preceptor of king Arjunavarman, Madana bore the title 'Bālasarasvatī'.[19] The inscription reports that the play was performed before Arjunavarman in the temple of Sarasvatī. This suggests that the inscription could have come from the site of a Sarasvatī temple.[20] The inscription is currently on display inside the building.

Grammatical inscriptions

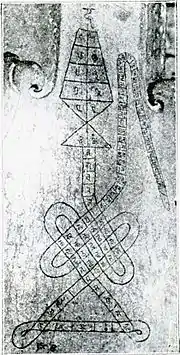

The building also contains two serpentine grammatical inscriptions. These records prompted K. K. Lele to describe the building as the Bhojśālā or Hall of Bhoja because king Bhoja was the author of a number of works on poetics and grammar, among them the Sarasvatīkaṇṭhābharaṇa or 'Necklace of Sarasvatī'.[21] The term Bhojaśālā was taken up by C. E. Luard and published in his Gazetteer of 1908 although Luard noted that it was a misnomer.[22] That the term Bhojśālā is due to Lele is shown by the writing of William Kincaid, in his "Rambles among Ruins in Central India," published in the Indian Antiquary, in 1888. This makes no mention of the term Bhojśālā, noting only the Akl ka kua or "Well of Wisdom" in front of the tomb of Kamāl al-Dīn. Kincaid was a cynical observer but in any case the absence of the term Bhojśālā in his text indicates was "no living tradition about the Bhojālā in the middle decades of the nineteenth century" among those with whom he interacted.[14]

Sarasvatī

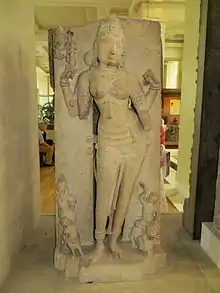

After Lele and Luard had identified the Bhojaśālā with the Kamāl Maula, O. C. Gangoly and K. N. Dikshit published an inscribed sculpture in the British Museum, announcing that it was Rāja Bhoja's Sarasvatī from Dhār.[23] This analysis was broadly accepted and had a significant impact. The statue in the British Museum was often identified as Bhoja's Sarasvatī in the years that followed.[24]

The inscription on the sculpture mentions king Bhoja and Vāgdevī, another name for Sarasvatī.[1] However, later study of the inscription by Indian scholars of Sanskrit and Prakrit languages, notably Harivallabh Bhayani,[25] demonstrated that inscription records the making of a sculpture of Ambikā after the making of three Jinas and Vāgdevī.[26] In other words, although Vāgdevī is mentioned, the inscription's main purpose is to record the making of an image of Ambikā, i.e. the sculpture on which the record is incised.[27]

Text and Translation

(1) auṃ | srīmadbhojanāreṃdracaṃdranagarīvidyādharī[*dha] rmmadhīḥ yo ----- [damaged portion] khalu sukhaprasthāpanā- (2) y=āp(sa)rāḥ [*|] vāgdevī[*ṃ] prathama[*ṃ] vidhāya jananī[m] pas[c] āj jinānāṃtrayīm ambā[ṃ] nityaphalā(d)ikāṃ vararuciḥ (m)ūrttim subhā[ṃ] ni- (3) rmmame [||] iti subhaṃ || sūtradhāra sahirasutamaṇathaleṇa ghaṭitaṃ || vi[jñā]nika sivadevena likhitam iti || (4) saṃvat 100 91 [||*]

Auṃ. Vararuci, King Bhoja's religious superintendent (Dharmmadhī) of the Candranagarī and Vidyādharī [branches of the Jain religion], the apsaras [as it were] for the easy removal [of ignorance? by...?], that Vararuci, having first fashioned Vāgdevī the mother [and] afterwards a triad of Jinas, made this beautiful image of Ambā, ever abundant in fruit. Blessings! It was executed by Maṇathala, son of the sūtradhāra Sahira. It was written by Śivadeva the proficient. Year 1091.

Iconography

The identification of the British Museum sculpture as Ambikā is confirmed by the iconographic features which conform to Ambikā images found elsewhere.[28] A particularly close comparative example is the Ambikā in Sehore dating to the eleventh century.[29] Like the Dhār sculpture, the Sehore image shows a youth riding a lion at the foot of the goddess and a figure with a beard standing at one side.

The inscription on the statue in the British Museum indicates that the Vāgdevī at Dhār was dedicated to the Jain form of Sarasvatī. However, the Vāgdevī mentioned no longer exists or is yet to be located. Merutuṅga, who wrote in the early fourteenth century, indicates that Bhoja's eulogistic tablets in the Sarasvatī temple were engraved with a poem dedicated to the first Jain Tīrthaṃkara, but these tablets too have not been located.[1][30]

Current status

The building is a Protected Monument of national importance under the laws of India and is under the jurisdiction of the Archaeological Survey of India. Both Hindus and Muslims claim the site, and use it for their prayers. According to Archaeological Survey of India guidelines, Muslims can pray on Friday and Islamic festivals, Hindus can pray on Tuesday and on the festival for goddess Sarasvatī, namely Vasant Panchami. The site is open to visitors on other days.[1][6]

The disputes about the site were prompted by the inscriptions and the information they provide about historic Indian religions, particularly Hinduism and Jainism. Data about Jainism comes from texts and a statue of the goddess Ambikā that is now housed in British Museum.[1] The area beside the Bhojśālā has four Islamic tombs of Sufi saints.[31] The most important is the tomb of Kamāl al-Dīn (circa 1238-1330), famous Chishti saint, who tomb was rebuilt under the Malwa Sultanate. Architecturally, the Bhojshala is earlier in date, and appears to be a hypostyle hall built of temple parts in the 1300s in a manner similar to the Quwwat-ul-Islam in the Qutb Minar complex, Delhi.[3]

Conflicts arise when the Vasant Panchami falls on Friday. The Archaeological Survey of India attempts to assign hours to both Hindus and Muslims on such days. However, this been a source of communal conflict and occasional disturbance when the religious group scheduled for the earlier time slot refuse to vacate the premises in time for the next.[4][5][6]

See also

Notes

References

- Willis, Michael (2012). "Dhār, Bhoja and Sarasvatī: from Indology to Political Mythology and Back". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 22 (1): 129–153. doi:10.1017/s1356186312000041.

- Ahmad Nabi Khan (2003). Islamic Architecture in South Asia: Pakistan, India, Bangladesh. Oxford University Press. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-0-19-579065-8.

- Willis, Michael (2012). "Dhār, Bhoja and Sarasvatī: from Indology to Political Mythology and Back". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 22 (1): 134–135. doi:10.1017/s1356186312000041., Quote: "Next to the tomb is a spacious hypostyle mosque built primarily of reused temple parts (Fig. 3)."

- Rajendra Vora; Anne Feldhaus (2006). Region, Culture, and Politics in India. Manohar. pp. 327–329. ISBN 978-81-7304-664-3.

- Indore celebrates Basant Panchmi, The Times of India, February 2, 2017

- Bhojshala-Kamal Maula mosque row: What is the dispute over the temple-cum-mosque all about?, India Today, Shreya Biswas (February 12, 2016)

- Willis, Michael (2012). "Dhār, Bhoja and Sarasvatī: from Indology to Political Mythology and Back". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 22 (1): 129–131. doi:10.1017/s1356186312000041.

- Venkatarama Raghavan, Bhoja’s Śṛṅgaraprakāśa, 3rd rev. ed. (Madras, 1940).

- E. Hultzsch, ‘Dhar Prasasti of Arjunavarman: Parijatamanjari-Natika by Mandana’, Epigraphica Indica 8 (1905-06): 96-122.

- C. H. Tawney, The Prabandhacintāmaṇi or Wishing-stone of Narratives (Calcutta, 1901)

- Louis H. Gray, The Narrative of Bhoja (Bhojaprabandha), American Oriental Series, vol. 34 (New Haven, 1950).

- K. K. Munshi, ed. Śṛṅgāramañjarīkathā, Siṅghī Jaina granthamālā, no. 30 (Bombay, 1959): 90.

- Swati Mitra (2009). Pachmarhi. Goodearth Publications. p. 71. ISBN 978-81-87780-95-3.

- Willis, Michael (2012). "Dhār, Bhoja and Sarasvatī: from Indology to Political Mythology and Back". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 22 (1): 136–138. doi:10.1017/s1356186312000041.

- Willis, Michael (2012). "Dhār, Bhoja and Sarasvatī: from Indology to Political Mythology and Back". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 22 (1): 141–143 with footnotes. doi:10.1017/s1356186312000041.

- John Malcolm, A Memoir of Central India including Malwa, and Adjoining Provinces (London, 1823). First published in Calcutta in 1821 then revised and expanded in two volumes for publication in London in 1823.

- Harivallabh Chunilal Bhayani, Rāula-vela of Roḍa: a rare poem of c. twelfth century in early Indo-Aryan (Ahmedabad: Parshva Prakashan, 1994).

- R. Pischel, Epigraphia Indica 8 (1905-06); V. M. Kulkarni, Kūrmaśatakadvayam: two Prakrit poems on tortoise who supports the earth (Ahmedabad: L.D. Institute of Indology, 2003).

- S. K. Dikshit, ed., Pārijātamañjarī alias Vijayaśrī by Rāja-Guru Madana alias Bāla-Sarasvatī (Bhopal, 1968). Available online, see: Dikshit, S. K. (1963). Pārijātamañjarī alias Vijayaśrī by Rāja-Guru Madana alias Bāla-Sarasvatī. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.375588.

- Zafar Hasan, EIM (1909-10): 13-14, pl. II, no. 2; Annual Report on Indian Epigraphy (1971-72): 81, no. D. 73.

- R. Birwé, ‘Nārāyaṇa Daṇḍanātha's Commentary on Rules III.2, 106-121 of Bhoja's Sarasvatīkaṇṭhābharaṇa’, Journal of the American Oriental Society 84 (1964): 150-62; the poetic text with this title, rather than the grammatical one, has been published as Sarasvatīkaṇṭhābharaṇam of King Bhoja, 3 vols., ed. and trans., Sundari Siddhartha (Delhi, 2009) ISBN 978-81-208-3284-8.

- C. E. Luard, Western States (Mālwā). Gazetteer, 2 parts. The Central India State Gazetteer Series, vol. 5 (Bombay, 1908): part A, pp. 494-500.

- O. C. Gangoly and K. N. Dikshit, ‘An Image of Saraswati in the British Museum’, Rūpam 17 (January, 1924): 1-2

- These mis-identifications are traced in M. Willis, "Dhār, Bhoja and Sarasvatī: From Indology to Political Mythology and Back," Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Corrected online version available here: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1154197

- Kirit Mankodi, ‘A Paramāra Sculpture in the British Museum: Vāgdevī or Yakshī Ambikā?’, Sambodhi 9 (1980-81): 96-103.

- M. Willis. "New Discoveries from Old Finds: A Jain Sculpture in the British Museum," CoJS Newsletter 6 (2011): 34-36, available online: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2544721

- M. Willis. "New Discoveries from Old Finds: A Jain Sculpture in the British Museum," CoJS Newsletter 6 (2011): 34-36, available online: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2544721.

- M. N. P. Tiwari, Ambikā in Jaina Art and Literature (New Delhi: Bharatiya Jnanpith, 1989).

- Sehore सीहोर (Madhya Pradesh). Ambikā. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3633937

- Tawney, Prabandhacintāmaṇi, p. 57.

- Ahmad Nabi Khan (2003). Islamic Architecture in South Asia: Pakistan, India, Bangladesh. Oxford University Press. pp. 175–177. ISBN 978-0-19-579065-8.

External links

Research Resources

- Karlsruher Virtueller Katalog

- About the KVK

- Internet Archives

- Jain Studies Newsletter, SOAS, London

- Acharya, Merutunga (1902). Prabandhacintamani. Asiatic Society.