Dhar

Dhar is a city located in the Malwa region in the west of the state of Madhya Pradesh in India. The city is the administrative headquarters of the Dhar District. Before Indian independence from Great Britain, it was the capital of the Dhar princely state.

Dhar | |

|---|---|

City | |

Dhar  Dhar | |

| Coordinates: 22.598°N 75.304°E | |

| Country | India |

| State | Madhya Pradesh |

| District | Dhar |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Council |

| • Body | Dhar Municipal Council |

| Elevation | 559 m (1,834 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 93,917 |

| Demonym(s) | Dharwasi |

| Language | |

| • Official | Hindi[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| Vehicle registration | MP-11 |

| Website | www |

Location

Dhar is situated between 21°57' to 23°15' N and 74°37' to 75°37' E. The city is bordered in the north by Ratlam, to the east by parts of Indore, in the south by Barwani, and to the west by Jhabua and Alirajpur. The town is located 34 miles (55 km) west of Mhow. It is located 559 m (1,834 ft) above sea level. It possesses, besides its old ramparts, many buildings contain records of cultural, historical and national importance.[2]

Climate

| Climate data for Dhar (1981–2010, extremes 1973–2011) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.4 (92.1) |

37.7 (99.9) |

43.1 (109.6) |

44.4 (111.9) |

47.1 (116.8) |

44.6 (112.3) |

39.6 (103.3) |

36.2 (97.2) |

38.3 (100.9) |

38.7 (101.7) |

34.8 (94.6) |

35.7 (96.3) |

47.1 (116.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 26.2 (79.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

33.8 (92.8) |

38.2 (100.8) |

39.9 (103.8) |

36.4 (97.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.0 (84.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

32.3 (90.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10.4 (50.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

11.9 (53.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

3.0 (37.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

16.6 (61.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.1 (43.0) |

4.1 (39.4) |

3.0 (37.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 4.0 (0.16) |

2.4 (0.09) |

1.7 (0.07) |

1.4 (0.06) |

11.5 (0.45) |

122.7 (4.83) |

269.7 (10.62) |

240.1 (9.45) |

146.4 (5.76) |

47.5 (1.87) |

21.5 (0.85) |

3.1 (0.12) |

872.1 (34.33) |

| Average rainy days | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 6.5 | 13.2 | 12.4 | 7.2 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 44.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 58 | 47 | 42 | 42 | 41 | 59 | 80 | 83 | 78 | 59 | 59 | 58 | 60 |

| Source: India Meteorological Department[3][4] | |||||||||||||

Historic places and monuments

The most visible parts of ancient Dhar are the massive earthen ramparts, which are best preserved on the western and southern sides of the town. These were most likely built at beginning of the 9th century. Wall remains show that the city was circular in plan and surrounded by a series of tanks and moats, similar to the city of Warangal, in the Deccan. The circular ramparts of Dhar, unique in north India and an important legacy of the Paramāras, are unprotected and have been slowly dismantled by brick-makers and others using the wall material for construction. On the north-east side of the town, the ramparts and moats have disappeared beneath modern homes and other buildings.

Fort

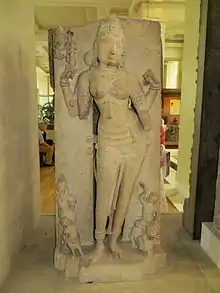

The historic parts of Dhar are dominated by an impressive sandstone fortress on a small hill. The fortress is thought to have been built by Muhammad bin Tughluq, the Sultan of Delhi, most likely on the site of the ancient Dharāgiri mentioned in early sources.[5] One of the gateways, added later, dates to 1684–85 in the time of 'Ālamgīr.[6] Inside the fort there is a deep rock-cut cistern of great age, and a later palace of the Mahārāja of Dhar that incorporates an elegant pillared porch from the Mughal period, possibly built in the mid-17th century. The palace area houses an outdoor museum with a small collection of temple fragments and images dating to medieval times.

Museum

Inside the fort, a large number of sculptures and antiquities from Dhar and its neighbourhood are kept in utilitarian buildings constructed in the late 19th century. Some pieces from the collection have been moved to Mandu where the Department of Archaeology, Museums and Archives has created a museum with a range of displays in the 'Barnes Koti', a Sultanate-period building used by Captain Ernest Barnes, the political agent of the Bhopawar agency.

Tomb of Shaykh Changāl

On the overgrown ramparts of the medieval city, overlooking the old moat, is the tomb of Shaykh Abdullah Shāh Changāl, a warrior saint. The tomb has been rebuilt, with its original inscription now incorporated into the compound gate. The inscription is written in Persian and has been dated to 1455. As a record of historical interest, it recounts the Shaykh's arrival in Dhar and his conversion of Bhoja to Islām after locals committed an atrocity against the small Muslim community who had settled in the city.[7] The story does not so much refer to King Bhoja but to a rising interest in Bhoja's biography in the 15th century and the attempts made at that time to appropriate his legacy in Sanskrit and Persian literature.[8]

Pillar Mosque

The Lat Masjid, or 'Pillar Mosque', located to the south of the town, was built as the Jami' Mosque by Dilawar Khan in 1405.[9] It derives its name from the iron pillar of Dhar("lāṭ" in Hindi), which is believed to have been set up in the 11th century.[10][11] The pillar, which is nearly 13.2 m high according to the most recent assessment, has fallen and broken; the three surviving parts are displayed on a small platform outside the mosque. It carries an inscription recording a visit by the Mughal emperor Akbar in 1598 while on a military campaign in the Deccan. The pillar's original stone footing is also displayed nearby.

Kamāl Maulā Campus

The Kamāl Maulā is a spacious enclosure containing four tombs, the most notable of them the tomb of Shaykh Kamāl Maulavi or Kamāl al-Dīn (circa 1238-1330). Maulavi was a follower of Farīd al-Dīn Gaṅj-i Shakar (circa 1173–1266, see Fariduddin Ganjshakar) and the Chishti saint Nizamuddin Auliya (1238–1325). Some details about Kamāl al-Dīn are recorded in Muḥammad Ghauthi's Azkar-i Abrar, a hagiography of Sufi saints written in 1613.[12] The cloak presented to Kamāl al-Dīn by Nizam al-Dīn is still displayed inside the tomb. The custodians of Kamāl al-Dīn's tomb have served continuously for 700 years.[13]

Bhoj Shala

Except for the Mihrab and Minbar, which were purpose-built for the monument, the hypostyle hall immediately next the tomb of Kamāl Maula is made of recycled temple columns and other architectural parts. It is similar to the Lāṭ Masjid, but was built earlier, as an inscription from 1392 described records of repairs by Dilāwar Khān.[14] In 1903, a Sanskrit and Prakrit inscription from the time of Arjunavarman (circa 1210-15) was found in the walls of the building by K. K. Lele, Superintendent of Education in the Princely State of Dhar. The engraved inscription is displayed inside the entrance. The text includes parts of a drama called Vijayaśrīnāṭikā composed by Madana, the king's preceptor, or 'Bālasarasvatī'.[15] Other inscribed tablets noted by Lele included a large tablet inscribed with the Kūrmaśataka — verses in praise of the Kūrma incarnation of Viṣhṇu — and a serpentine inscription containing the grammatical rules of the Sanskrit language. These finds, particularly the grammatical inscription, prompted Lele to name the building Bhoj Shala, or 'Hall of Bhoja', in reference to King Bhoja (circa 1000-55), the author of several works on poetics and grammar such as the famous Sarasvatīkaṇṭhābharaṇa or 'Necklace of Sarasvatī'.[16] The term 'Bhoj Shala' was first published by C.E. Luard in 1908.[17]

Cenotaphs and Old City Palace

The old city palace of the Puar (Pawar) clan, a branch of the Marathas, is now used as a school. It is a plain, medium-sized building built around 1875. A marble statue of the Jain goddess Ambikā, discovered on the site of the palace in 1875, is now in the British Museum.[19] Of the same time period as the palace are a collection of domed cenotaphs of the Powar rulers on the edge of the large tank known as Muñj Talab. The name of the tank was probably derived from Vākpati Muñja (10th century), the first Paramāra king that entered Mālwa and made Ujjain his main administrative seat.[20]

Agency House

Another colonial era building at Dhar, located outside the old town on the road to Indore, is the Agency House. It was built by the Public Works Department during British rule and was the center of the administration of Dhar State and the Central India Agency.[21] The building has been abandoned and is now in ruins.

Jheera Bagh

In the 1860s, the Powars built a palace at Hazīra Bāgh, adjacent to the road to Māṇḍū. Known as the Jheera Bāgh Palace, the complex was renovated by Mahārāja Anand Rao Pawar IV in the 1940s and is now run as a heritage hotel. Designed in an unpretentious art deco style, it is considered to be one of the most elegant and forward-looking examples of early modern architecture in North India.

Political history

The town of Dhar, derived from Dhārā Nagara ('city of sword blades'), is of considerable antiquity,[2] the first reference to it appearing in an inscription in Jaunpur during the Maukhari dynasty (6th century).[22] Dhar rose to prominence when it was made the primary seat of the Paramara chiefs of Malwa by Vairisiṃha (circa 920-45 CE). Vairisimha appears to have transferred his headquarters to Dhar from Ujjain. During the rule of the Paramāras, Dhar was a respected centre of culture and learning,[2] especially under the rule of King Bhoja (circa 1000-1055). The wealth and splendor of Dhar drew the attention of competing dynasties in the 11th century. The Cāḷukyas of Kalyāṇa under Someśvara I (circa CE 1042-68) captured and burnt the city, also occupying Māṇḍū (ancient Māṇḍava).[23] Dhar was subsequently sacked by the Cāḷukyas of Gujarāt under Siddharāja.[24] The devastation and political fragmentation caused by these wars meant that there was no significant opposition when Ala ud din Khilji, the Sultān of Delhi, dispatched an army to Mālwa in the early 14th century. The region was annexed to Delhi, and Dhar was made the capital of the province under 'Ayn al-Mulk Mūltānī, who served as governor until 1313.[25] The events that occurred during the following seventy years are unclear, but some time in A.H. 793/C.E. 1390-91 Dilawar Khan was appointed muqṭi' of Dhar (and also the governor of Mālwa) by Sulṭān Muḥammad Shāh.[26] Dilāwar Khān took the title 'Amīd Shāh Dā'ūd' and mandated the khutba to be read in his name in A.H. 804/C.E. 1401-02, thereby establishing himself as an independent sulṭān.[27] Upon his death in 1406, his son Hoshang Shah became king, with his capital situated in Māṇḍū. In the time of Akbar, Dhar fell under the dominion of the Mughals, and remained under Mughal control until 1730, when the town was conquered by the Marathas.[2]

In late 1723, Bajirao, at the head of a large army and accompanied by his lieutenants Malharrao Holkar, Ranoji Shinde (Scindia) and Udaji Rao Pawar, swept through Malwa. A few years earlier, the Mughal Emperor had been forced to relinquish to the Marathas the right to collect Chauth taxes in Malwa and Gujarat. This levy was financially beneficial to the Marathan caste, as both the king Shahu and his Peshwa, Bajirao, were in large amounts of debt at the time. Agriculture in the Deccan depended heavily on the timeliness and duration of the monsoons. The most important source of royal revenue was, therefore, the Chauth (a 25% tax on produce) and Sardeshmukhi (a ten per cent surcharge) exacted by the Marathas. The revenues the Marathas collected from their own lands were not sufficient to run the administration of their state and finance their large military expenditure, as their government was focused on conquest and not economic development.

The Marathan armies eventually defeated the Mughal governor and attacked the capital Ujjain. Bajirao established military outposts in the country as far north as Bundelkhand.

Towards the end of the 18th century and in the early part of the 19th century, the Marathan state was subject to a series of spoliations by Scindia of Gwalior and Holkar of Indore, (descendants of Ranoji Scindia and Malharao Holkar), but was saved from annihilation by the strong rule of the adoptive mother of the fifth raja.

Dhar State

After the Third Anglo-Maratha War of 1818, Dhar fell under British rule. The Dhar State was designated as a princely state of British India, in the Bhopawar Agency of the Central India Agency. It included several Rajput and Bhil feudatories and had an area of 1,775 square miles (4,600 km2). The state was confiscated by the British after the Revolt of 1857. In 1860, it was restored to Raja Anand Rao III Pawar, then a minor, with the exception of the detached district of Bairusia which was granted to the Begum of Bhopal. Anand Rao, who received the personal title Maharaja and the KCSI in 1877, died in 1898; he was succeeded by Udaji Rao II Pawar.[2]

Dhar Thikanas

A separate department whose purpose was to superintend Thakurs and Bhumias, called "Department of Thakurans, Bhumians and Thikanejat", was established in 1921. At the time there were 22 such estates in the state of Dhar.

The jagir lands of the nobles of Dhar (feudatory estates), all of whom paid tribute to the Darbar, were divided between Thakurs and Bhumias.

The Thakurs, with a few exceptions, were Rajput landholders whose estates were located in the north of the state. Locally, the Thakurs were called Talukdars and their holdings called kothari. By caste, there were 8 Rathor, one Pawar and one Kayasth Rajputs.

The Bhumias, or "Allodial" Chiefs, were all Bhilalas, a clan claiming to be of mixed Bhil and Rajput (Chauhan) descent. Their grants were originally obtained from the Darbar on the understanding that they would keep the peace among the Bhils and other hill tribes. They paid yearly tribute to the Darbar, in turn receiving cash allowances (Bhet-Ghugri), an ancient feudal custom.

Political representation and Royal Legacy

Bhartiya Janata Party politician Neena Vikram Verma serves as a member of the Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly for the Dhar-Vidhan-Sabha Constituency.[28]

In 2019, Chattar Singh Darbar of the Bharatiya Janata Party was elected as a Member of Parliament representing the Dhar constituency.[29]

Maharaja Shrimant Hemendra Singh Rao Pawar is the present titular head of the Kshatriya Maratha-Rajput Pawar (Puar/Parmar) dynasty of the State of Dhar.[30][31][32][33][34]

Demographics

As of the 2011 Indian Census, Dhar had a total population of 93,917, of which 48,413 were males and 45,504 were females. 11,947 were between 0 and 6 years old. The total number of literate people in Dhar was 68,928. 73.4% of the population was literate, with a male literacy rate of 78.1% and a female literacy rate of 68.4%. The literacy rate of the 7+ population in Dhar was 84.1%, of which the male literacy rate was 89.9% and the female literacy rate was 78.0%. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes population was 7,549 and 16,636 respectively. As of 2011, Dhar has 18531 households.[35]

This is an increase from the 2001 India census,[36] when Dhar had a population of 75,472, of which males constituted 52% and females 48%. In 2001, Dhar had an average literacy rate of 70%, higher than the national average of 59.5%. Male literacy was 76% and female literacy was 63%. In 2001, 14% of the population of Dhar was under 6 years of age.

Postal information

In 1897, primitive stamps with entirely native text were issued. The second definitive issue bore the name "Dhar State" in Latin script; with a total of 8 stamps. Since 1901, Indian stamps have been in use in Dhar.

Notable people

Baji Rao II, the last of the Peshwas, was born in Dhar.[38]

Gallery

District Archaeological Museum, Dhār, Madhya Pradesh

District Archaeological Museum, Dhār, Madhya Pradesh Kharbuza Mahal at the Dhār Fort

Kharbuza Mahal at the Dhār Fort Kharbuza Mahal at the Dhār Fort

Kharbuza Mahal at the Dhār Fort Kharbuza Mahal at the Dhār Fort

Kharbuza Mahal at the Dhār Fort Entire view of Bawari (Water Source at the Dhār Fort)

Entire view of Bawari (Water Source at the Dhār Fort) Entrance view from inside the fort at Dhār

Entrance view from inside the fort at Dhār Outer view of the fort at Dhār

Outer view of the fort at Dhār The Dhār Fort

The Dhār Fort

See also

References

- "52nd Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dhar". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 142.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dhar". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 142. - "Station: Dhar Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 239–240. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M117. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- K. K. Lele, in Dikshit, Pārijātamañjarī, p. xxi, n. 1,

- Annual Report on Indian Epigraphy (1971-72): 81, no. D. 72.

- G. H. Yazdani, ‘The Inscription on the Tomb of ‘Abdullah Shāh Changāl at Dhār’ Epigraphica Indo-Moslemica (1909-10): 1-5; now translated and reinterpreted in Golzadeh, Razieh B. (2012). "On Becoming Muslim in the City of Swords: Bhoja and Shaykh Changāl at Dhār". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 22 (1): 115–27. doi:10.1017/S1356186311000885.

- The point made in Golzadeh, Razieh B. (2012). "On Becoming Muslim in the City of Swords: Bhoja and Shaykh Changāl at Dhār". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 22 (1): 115–27. doi:10.1017/s1356186311000885.

- Annual Report on Indian Epigraphy (1971-72): 81, no. D. 73

- Smith, V. A. "The Iron Pillar of Dhār". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 1898: 143–46.

- Ray, Amitava; Dhua, S. K.; Prasad, R. R.; Jha, S.; Banerjee, S. (1997). "The ancient 11th century iron pillar at Dhar, India: a microstructural insight into material characteristics". Journal of Materials Science Letters. 16 (5): 371–375. doi:10.1023/A:1018550529070. S2CID 134653889.

- Muḥammad Ghauthi Mandawi, Azkar-i abrar, Urdu Tarjuma-i Gulzar-i Abrar, trans. Fazl Ahmad Jewari [Urdu lithograph] (Agra: Matba`-i Mufid-i `Amm, 1326/1908, reprint ed., Lahore: Islamic Book Foundation, 1395/1975): 581.

- The key modern works in Rām Sevak Garg, Hazrat maulānā kamāluddīn ciśtī rah. aur unkā yug (Bhopāl, 2005).

- Luard, Dhar and Mandu (Bombay, 1916): 9; U. N. Day, Medieval Malwa (Delhi, 1969): 15, n. 2.

- S. K. Dikshit, ed., Pārijātamañjarī alias Vijayaśrī by Rāja-Guru Madana alias Bāla-Sarasvatī (Bhopal, 1968).

- R. Birwé, ‘Nārāyaṇa Daṇḍanātha's Commentary on Rules III.2, 106-121 of Bhoja's Sarasvatīkaṇṭhābharaṇa’, Journal of the American Oriental Society 1964; 84: 150-62.

- C. E. Luard, Western States (Mālwā). Gazetteer, 2 parts. The Central India State Gazetteer Series, vol. 5 (Bombay, 1908): part A, pp. 494-500; also Luard, Dhar and Mandu, p. 9

- "British Museum Collection".

- Kirit Mankodi, ‘A Paramāra Sculpture in the British Museum: Vāgdevī or Yakshī Ambikā?’, Sambodhi 9 (1980-81): 96-103.

- H. V. Trivedi, Inscriptions of the Paramāras, Chandellas, Kachchhapaghātas and Two Minor Dynasties, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, volume 7 (New Delhi, 1978-91): 9.

- The only documentation is here: Agency House

- J. F. Fleet, Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings and their Successors, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. 3 (Calcutta, 1888): 228 (line 6). Hans T. Bakker, 'The So-Called Jaunpur Inscription of Īśvaravarman', Indo-Iran Journal 2009; 50: 207-16 shows that inscription belongs not to Īśvaravarman but to Īśānavarman or one of his successors. Online abstract: http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/10.1163/001972409x12525778274224

- G. Yazdani, ed., The Early History of the Deccan, 2 vols. (London, 1960) 1: 331 according to the Nander inscription (dated CE 1047) and Nāgai inscription (dated CE 1058).

- A. K. Majumdar, Chalukyas of Gujarat (Bombay, 1956): 72-3.

- Iqtidar Husain Siddiqui, Authority and Kingship under the Sultans of Delhi (Delhi, 2006): 283-84.

- Day, Medieval Malwa, p. 13.

- Day, Medieval Malwa, p. 21.

- "Madhya Pradesh Pollmeter: Never too late". The Hindu. 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "Dhar Election Results 2019 Live Updates: ChattarSingh Darbar of BJP Wins". News18. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "Hemendra Singh Puar is head of erstwhile princely state of Dhar". Hindustan Times. 15 January 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- "Hemendra Puar to be new Dhar maharaja | Indore News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- "Hemendra Singh becomes new King of Dhar". Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- "Administration to remove seal on Dhar royal estates on HC orders | Indore News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- Solomon, R. V.; Bond, J. W. (2006). Indian States: A Biographical, Historical, and Administrative Survey. ISBN 9788120619654.

- "Census of India: Dhar". www.censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- "Census of India 2001: Data from the 2001 Census, including cities, villages and towns (Provisional)". Census Commission of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- "C-1 Population By Religious Community". census.gov.in. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer p. 510

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dhar |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dhar. |

- DhārDistrict governmental website

- Dhārat the Islamic Monuments of India Photographic Database

- More Information about Mandu near Dhar