Kurma

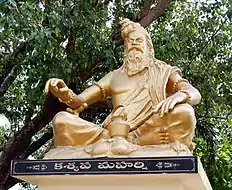

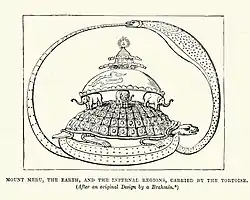

Kurma (Sanskrit: कूर्म; Kūrma, 'turtle', 'tortoise'), also known as 'KurmaRaja' ('Tortoise King') is an avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu. Originating in Vedic literature such as the YajurVeda as being synonymous with the Saptarishi called Kasyapa, Kurma is most commonly associated in post-Vedic literature such as the Puranas with the legend of the churning of the Ocean of Milk, referred to as the Samudra manthan. Also synonymous with Akupara, the world-turtle supporting the Earth, Kurma is listed as the second incarnation of the Dashavatara, the ten principal avatars of Vishnu.

| Kurma | |

|---|---|

Firmness, Support | |

| Member of Dashavatara | |

Half-human and Half-Tortoise depiction of Vishnu | |

| Devanagari | कूर्म |

| Affiliation | Vishnu (second avatar) |

| Abode | Bharata Khanda, Vaikuntha |

| Weapon | None |

| Festivals | Kurma Jayanti (Vaisakh month during the Shukla Paksha) |

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

Nomenclature and Etymology

The Sanskrit word 'Kurma' (Devanagari: कूर्म) means 'tortoise' and 'turtle'.[1] 'Kurmaraja' (कूर्मराज) means 'king of tortoises or turtles'.[2] The tortoise avatar of Vishnu is also referred to in post-Vedic literature such as the Bhagavata Purana as 'Kacchapam' (कच्छप), 'Kamaṭha' (कमठ), 'Akupara' (अकूपार), and 'Ambucara-ātmanā' (अम्बुचर-आत्मना), all of which mean 'tortoise' or 'form of a tortoise'.[3][4][5][6]

The Nirukta

Written by the grammarian Yaska, the Nirukta is one of the six Vedangas or 'limbs of the Vedas', concerned with correct etymology and interpretation of the Vedas. The entry for the Tortoise states (square brackets '[ ]' are as per the original author):

May we obtain that illimitable gift of thine. The sun is called akupara also, i. e. unlimited, because it is immeasurable. The ocean, too, is called akupara, i. e. unlimited, because it is boundless. A tortoise is also called a-kupa-ara, because it does not move in a well [On account of its shallowness]. Kacchapa (tortoise) is (so called because) it protects (pati) its mouth (kaccham), or it protects itself by means of its shell (kacchena), or it drinks (√pa) by the mouth. Kaccha (mouth or shell of a tortoise) = kha-ccha, i. e. something which covers (chddayatl) space (kham). This other (meaning of) kaccha, 'a bank of a river', is derived from the same (root) also, i.e. water (kam) is covered (chadyate) by it.

— The Nighantu and the Nirukta [of Yaska], translated by Lakshman Sarup (1967), Chapter 4, Section 18[7]

Kasyapa

As illustrated below, Vedic literature such as the SamaVeda and YajurVeda explicitly state Akupara/Kurma and the sage Kasyapa are synonymous. Kasyapa - also meaning 'Tortoise' - is considered the progenitor of all living beings with his thirteen wives, including vegetation, as related by H.R. Zimmer:

Ira [meaning 'fluid']... is known as the queen-consort of still another old creator-god and father of creatures, Kashyapa, the Old Tortoise Man, and as such she is the mother of all vegetable life.

— Myths And Symbols In Indian Art And Civilization by Heinrich Robert Zimmer, 1946), Chapter 6[8]

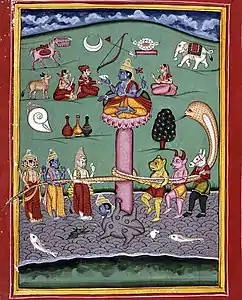

The legend of the churning of the Ocean of Milk (Samudra manthan) developed in post-Vedic literature is itself inextricably linked with Kurma (as the base of the churning rod) and involves other sons of Kasyapa: the Devas/Âdityas (born from Aditi) and the Asuras/Danavas/Daityas (born from Danu and Diti) use one of the Naga (born from Kadru) as a churning rope to obtain Amrita. Garuda, the king of birds and mount of Vishnu, is another son of Kasyapa (born from Vinata) often mentioned in this legend. In another, Garuda seeks the Amrita produced (eating a warring Elephant and Tortoise in the process) to free his mother and himself from enslavement by Kadru.

The Body (Air and Arteries)

M. Vettam notes that there are ten Vayus (winds) in the body, one of which is called 'Kurma' in regards to opening and closing the eyes.[9]

The 'kurma-nadi' (or Kūrmanāḍī, Sanskrit कूर्मनाडी), meaning 'tortoise-nerve' or 'canal of the tortoise', is in relation to steadying the mind (slowing down thoughts) in Yogic practice.[10] 'Nadi' itself means 'vein', 'artery', 'river', or 'any tubular organ of the body' (as well as 'flute').[11] Although the Kūrmanāḍī is generally stated to be located in the upper chest below the throat,[10] S. Lele believes this refers to the Muladhara Chakra, located near the tailbone, based on the root-word 'nal' (Sanskrit नल्), meaning 'to bind'.[12][13]

These are all mentioned in the Upanishads and Puranas (see below).

Yogic Practice / Ritual Worship

Kurmasana (Tortoise Posture) is a Yoga posture. 'Panikacchapika' (Sanskrit पाणिकच्छपिका), meaning 'hand tortoise',[14] is a special positioning of the fingers during worship rituals to symbolise Kurma. The Kurmacakra is a yantra, a mystical diagram for worship,[15] in the shape of a tortoise. These are all mentioned in the Upanishads and Puranas (see below).

Symbolism

Firmness / Steadiness: W. Caland notes that in relation to 'Akupara Kasyapa' in the Pancavimsa Brahmana and Jaiminiya Brahmana, the tortoise is equal to 'a firm standing... and Kasyapa (the Tortoise) is able to convey (them) across the sea [of material existence]'.[16] P.N. Sinha seems to support this view, adding 'Kurma was a great Avatara as He prepared the way for the spiritual regeneration of the universe, by the Churning of the ocean of Milk'.[17]

Deity Yajna-Purusha: N. Aiyangar states that as the tortoise was 'used as the very basis of the fire altar, the hidden invisible tortoise, taken together with the altar and the sacred fire, seems to have been regarded as symbolizing the Deity Yajna-Purusha who is an invisible spiritual god extending from the fire altar up to heaven and everywhere... this seems to be the reason why the tortoise is identified with the sun'.[18]

Meditation / Churning the Mind: Aiyangar also surmises that the legend of the Samudra manthan symbolises churning the mind through meditation to achieve liberation (moksha). Based on the mention of Vātaraśanāḥ ('girdled by the wind') Munis in the Taittirtya Aranyaka - also referred to as urdhvamanthin, meaning 'those who churn upwards' - and the explanation provided in the Shvetashvatara Upanishad, Aiyangar believes this would 'appear to be the hidden pivot on which the gist of the riddle of the Puranic legend about the churning for nectar turns'.[18] R. Jarow seems to agree, stating the churning of the Ocean of Milk represents the 'churning of the dualistic mind'.[19]

._The_figure_here_indicated_by_the_fingers_is_meant_to_represent_it..jpg.webp)

Ascetic Penance: H.H. Wilson notes that 'the account [of the Samudra manthan] in the Hari Vamsa... is explained, by the commentator, as an allegory, in which the churning of the ocean typifies ascetic penance, and the ambrosia is final liberation' (linking with the idea of 'steadiness' and 'firmness'), but personally dismisses this interpretation as 'mere mystification' (Note 1, pp. 146).[20]

Astronomy: B.G. Sidharth states that the legend of the Samudra manthan symbolises astronomic phenomena, for example that 'Mandara represents the polar regions of Earth [and the] churning rope, Vasuki, symbolizes the slow annual motion of Earth... Vishnu, or the Sun himself rests upon a coiled snake... which represents the rotation of the Sun on its own axis'. In regards to the tortoise supporting the Earth, Sidharth adds that the 'twelve pillars... are evidently the twelve months of the year, and... The four elephants on which Earth rests are the Dikarin, the sentinels of the four directions.. [Kurma] symbolizes the fact that Earth is supported in space in its annual orbit around the Sun'.[21]

Extension and Withdrawal: As illustrated throughout this article, the tortoise extending and retracting its limbs is often mentioned allegorically in the Itihāsa (epics) and Puranas in regards to various subjects, particularly self-control and detachment.

The Vedas

A.A. Macdonell, A.B. Keith, J. Roy, J. Dowson, and W.J. Wilkins all state that the origin of Kurma is in the Vedas, specifically the Shatapatha Brahmana (related to the YajurVeda), where the name is also synonymous with Kasyapa, one of the Saptarishi (seven sages).[22][23][24][25][26] Macdonell adds that although the Shatapatha Brahmana also states all creatures are 'descended from Kasyapa', and lists this as the name of a Brahmin family in the RigVeda (along with other animal-based tribal names such as Matsya), he acknowledges academics such as E.W. Hopkins 'doubt whether the names of animals ever point to totemism'.[22]

Rig Veda

| Rig | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 9.114,[27] 10.136[28] | Hymn 9.114 names the sage Kasyapa, later synonymous with Kurma (see YajurVeda section). |

2. The Munis, girdled with the wind [vātaraśanāḥ], wear garments soiled of yellow hue.

They, following the wind's swift course go where the Gods have gone before...

7. Vāyu hath churned for him: for him he poundeth things most hard to bend,

When he with long loose locks hath drunk, with Rudra, water [viṣá] from the cup.— Rig Veda (translated by R.T.H. Griffith, 1896), Book 10, Hymn 136, Verses 2 and 7

Verse 2 is significant as Aiyangar states that the vātaraśanāḥ Munis ('girdled by the wind', explained as 'Vata = wind, rasana = rope, girdle') were known as sramanas ('derived from sram, [meaning] to exert very much, to practice austerity') and as urdhvamanthins, meaning 'those who churn upwards'. To explain what to 'churn upwards' means, Aiyangar quotes from the Shvetashvatara Upanishad (1.14; text in square '[ ]' and round '( )' brackets are as quoted by the author):

Making his atman (mind) the lower arani wood and the syllable Om [repeated in the Japa dhyana] the upper wood, and by churning again and again with (the rope of) dhyana (contemplation), man should see the Lord like the hidden [fire generated by attrition].

— Essays On Indo Aryan Mythology by Narayan Aiyangar ('The Tortoise')[18]

There is disagreement amongst academics as to whether the term 'vātaraśanāḥ' (i.e. 'girdled by the wind') refers to being naked (i.e. only clothed by the wind) or severe austerity (i.e. sramana).[29][30] Aiyangar argues that austerity is the correct interpretation as the RigVeda clearly states the vātaraśanāḥ Munis are wearing garments, and because the 'unshaven long-haired Muni [stated to have 'long locks' in verse 6] cannot have been an ascetic of the order of sannyasin... who shaved his head'.[18] P. Olivelle agrees, stating the term changed from meaning 'ascetic behaviour' to 'a class of risis' by the time of the Taittirtya Aranyaka,[29] in which the vātaraśanāḥa Munis appear with Kurma (see YajurVeda section, below).

Verse 7 is significant as in addition to mentioning the wind-god Vayu 'churning' the vātaraśanāḥ Munis 'following the wind's swift course', although R.T.H. Griffith translated 'viṣá' (Sanskrit विष) as Rudra drinking water, Aiyangar states it also means 'poison' (in this verse as 'keśīviṣasya', Sanskrit: केशीविषस्य)[31][32][33] and quotes Dr. Muir as stating that 'Rudra [Shiva] drinking water (visha) may possibly have given rise to the legend of his drinking poison (visha)' in the Samudra manthan.[18]

Sama Veda

| Sama | References | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancavimsa Brahmana | 15.5.30[16] | This verse is in regards to Kasyapa, synonymous with Kurma ('tortoise'). | |

| Jaiminiya Brahmana | 3.210[16] | As stated by W. Caland in his translation of the Pancavisma Brahmana. Caland's German translation of the Jaiminiya Brahmana with this verse is available.[34] | |

29. There is the akupara(-saman). ('The chant of Akupara'). 30. By means of this (saman), Akupara Kasyapa attained power and greatness. Power and greatness attains he who in lauding has practised the akupara(saman).

— Pancavimsa Brahmana (translated by W. Caland, 1931), Prapathaka XV (15), Khanda 5, Verses 29-30

The sage Kasyapa - stated in the Vedas, Itihāsa (epics), and Puranas to be the progenitor of all living beings (see relevant sections, below) - is also stated to be synonymous with Akupara, the name of the 'world-turtle' in the Mahabharata. Caland explains in his footnote to verse 30 the significance of this name by quoting from the Jaiminiya Brahmana:[16]

Akupara Kasyapa descended together with the Kalis, into the sea. He sought it in firm standing. He saw this atman and lauded with it. Thereupon, he found a firm standing in the sea, viz., this earth. Since that time, the Kalis sit on his back. This saman is (equal to) a firm standing. A firm standing gets he who knows thus. The Chandoma(-day)s are a sea... and Kasyapa (the tortoise) is able to convey (them) across the sea. That there is here this akupara, is for crossing over the sea.

— Pancavimsa Brahmana (translated by W. Caland, 1931), Note 1 (extract from Jaiminiya Brahmana, 210), pp. 407

The Jaiminiya Brahmana explicitly links Akupara, Kasyapa, and the tortoise in regards to providing a 'firm standing' to cross over the sea of material existence. As illustrated below, in the YajurVeda, Kasyapa is also stated to be synonymous with Prajapati (i.e. the creator-god Brahma) and with Kurma. In the Puranas, Kasyapa is frequently referred to as 'Prajapati' as well.

Yajur Veda

| Yajur | References | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Śukla (White) Shakha | Vajasaneyi Samhita | 13.31,[35] 24.34, 24.37;[36] 25.3[37] | These are in relation to tortoises, rather than Kurma, specifically. | |

| Shatapatha Brahmana | 1.6.2.3-4,[38] 6.1.1.12,[39] 7.5.1.5-7[40] | This is generally agreed to be the origin of the Kurma avatar, and links Kasyapa. | ||

| Taittiriya (Black) Shakha | Taittiriya Samhita | 2.6.3,[41] 5.2.8, 5.7.8, 5.7.13[42] | Links Prajapati (i.e. Brahma), Vishnu, and tortoises as the base 'bricks' in sacrifice to achieve liberation. | |

| Taittiriya Aranyaka | I.23-25[18][43] | As stated by Aiyangar and Macdonell | ||

| Shvetashvatara Upanishad | 1.14, 2.5[44] | This Upanishad is from the Taittiriya Aranyaka. Swami Tyagisananda translates the churning verse as the body being the lower piece of wood, whereas Aiyangar quotes the Atman (translated as 'mind') as the lower piece of wood. | ||

Shukla (White) YajurVeda

31. He crept across the three heaven-reaching oceans, the Bull of Bricks, the Master of the Waters.

— White Yajurveda (translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith, 1899), Book 13, Verse 31

Macdonell states that in the above-quoted verse, Kurma 'is raised to the semi-divine position as 'lord [or master] of waters'.[22] Verse 24.34 states that 'the tortoise belongs to Heaven and Earth' and Verse 24.37 states that the tortoise - along with the doe-antelope and iguana - 'belong to the Apsarases' (spirits of clouds and water). The translator, R.T.H. Griffith, makes several notes in the Shukla YajurVeda regarding the use and symbolism of tortoises. This includes remarking in book 13, that the tortoise was buried in 'ceremonies connected with the construction of the Ahavaniya Fire-Altar'.[45] Other notes made by Griffith in regards to sacrificial ritual practice with the corresponding texts (i.e. verses) include:

- Verse 13.30 (pp. 118): 'He lays down the tortoise on a bed of Avaka plants on the right side of the brick Invincible... The tortoise may have been chosen here with reference to the belief that the world rests upon a tortoise as an incarnation of Vishnu.'

- Verse 13.31 (pp. 118): 'He keeps his hand on the tortoise and shakes it as he recites the text'.

- Verse 13.31 (pp. 118): 'He puts the tortoise on the altar site with the text.'

The tortoise is also mentioned in the Shatapatha Brahmana:

1. He then puts down a (living) tortoise [on the altar];--the tortoise means life-sap: it is life-sap (blood) he thus bestows on (Agni). This tortoise is that life-sap of these worlds which flowed away from them when plunged into the waters: that (life-sap) he now bestows on (Agni). As far as the life-sap extends, so far the body extends: that (tortoise) thus is these worlds.

2. That lower shell of it is this (terrestrial) world; it is, as it were, fixed; for fixed, as it were, is this (earth-)world. And that upper shell of it is yonder sky; it has its ends, as it were, bent down; for yonder sky has its ends, as it were, bent down. And what is between (the shells) is the air;--that (tortoise) thus is these worlds: it is these worlds he thus lays down (to form part of the altar)...

5. And as to its being called 'kûrma' (tortoise); Prajapati, having assumed that form, created living beings. Now what he created, he made; and inasmuch as he made (kar), he is (called) 'kûrma;' and 'kûrma' being (the same as) 'kasyapa' (a tortoise), therefore all creatures are said to be descended from Kasyapa.

6. Now this tortoise is the same as yonder sun: it is yonder sun he thus lays down (on the altar)... On the right (south) of the Ashâdhâ [Altar Brick] (he places it), for the tortoise (kûrma, masc.) is a male, and the Ashâdhâ a female...— Yajur Veda (Shatapatha Brahmana, translated by Julius Eggeling, 1900), Kanda VII, Fifth Adhyâya (First Brâhmana), Verses 1-6

'Ashâdhâ' means 'of a brick used for the sacrificial altar'.[46] The Shatapatha Brahmana explicitly states the Tortoise forms part of the sacrificial altar, that it represents the Earth and the Sun, and that it 'is the breath, for the breath makes (kar) all these creatures' (verse 8). The remainder of this Brahmana details the process of carrying out the sacrifice. Notably, several references are made to Vishnu as the performer and enjoyer of the sacrifice. Thus, the tortoise - Kurma - is explicitly linked with Vishnu.

Kurma is also stated to be the origin of all creatures and synonymous with the sage, Kasyapa, repeatedly stated throughout Puranic literature to be a 'Prajapati', i.e. the origin of all living creatures. Dowson states 'authorities agree in assigning him [Kasyapa] a large part in the work of creation', as one of the seven great rishis (Saptarishi) and the guru of both the Parasurama and Rama avatars of Vishnu.[47]

Krishna (Black) YajurVeda

Relating to the tortoise being the 'Bull of Bricks' in the Shukla YajurVeda, Aiyangar states that the Taittiriya Samhita (5.2.8) 'speaks of the ritual of burying a living tortoise underneath the altar, and says that the tortoise thus buried will lead the sacrificer to Suvarga, Heaven':[18]

...verily he piles the fire with Prajapati. The first brick that is put down [for an altar] obstructs the breath of cattle and of the sacrificer; it is a naturally perforated one, to permit the breath to pass, and also to reveal the world of heaven... Now he who ignorantly puts down a brick is liable to experience misfortune... When the Angirases went to the world of heaven, the sacrificial cake becoming a tortoise crawled after them; in that he puts down a tortoise, just as one who knows a place leads straight (to it), so the tortoise leads him straight to the world of heaven... He puts it down to the east, to attain the world of heaven; he puts it down to the east facing west; therefore to the east facing west the animals attend the sacrifice... the sacrifice is Visnu, the trees are connected with Visnu; verily in the sacrifice he establishes the sacrifice.

— Black Yajur Veda (Taittiriya Sanhita, translated by Arthur Berriedale Keith, 1914), Kanda V, Prapathaka II ('The Preparation of the Ground for the Fire')

The building of sacrificial altars are directly connected with Prajapati. Macdonell also notes another instance in the Taittiriya Samhita (2.6.3) where Prajapati assigns sacrifices for the gods and places the oblation within himself, before Risis arrive at the sacrifice and 'the sacrificial cake (purodasa) is said to become a tortoise'.[22] The Taittiriya Samhita (e.g. 5.3.1) also describes the use of bricks - real bricks made of clay/earth ('istaka') and symbolic 'bricks' of water ('ab-istaka') and Durva grass - for the construction of real and symbolic altars for rituals (e.g. cayana) and oblations (yajna).[48]

F. Staal and D.M. Knipe both state that the creation, numbers, and configuration or layering of bricks - real and symbolic - had numerous rules, with Staal adding that 'Vedic geometry developed from the construction of these and other complex altar shapes'.[49][50] The use of bricks to build fire-altars for oblations to achieve liberation (moksha) is also mentioned by Yama to Nachiketa in the Katha Upanishad (1.15).[51] Aiyangar also quotes from the Taittiriya Aranyaka, where 'the Tortoise Kurma is, in this story also, the maker of the universe':[18]

The waters, this (universe), were salilam (chaotic liquid) only. Prajapati alone came into being on a lotus leaf. Within his mind, desire (Kama) around as 'Let me bring forth this (universe).' Therefore what man gets at by mind that he utters by word and that he does by deed... He (Prajapati desired to bring forth the universe) performed tapas (austere religious contemplation). Having performed tapas, he shook his body. From his flesh sprang forth Aruna-Ketus, (red rays as) the Vatarasana Rishis, from his nakhas, nails, the Vaikhanasas, from his valas, hair, the Valakhilyas, and his rasa, juice, (became) a bhutam (a strange being, viz.,) a tortoise moving in the middle of the water. He [Prajapati] addressed him thus 'you have come into being from my skin and flesh.' 'No,' he replied, 'I have been here even from before (purvan eva asam).' This is the reason of the Purusha-hood of Purusha. He (the tortoise) sprang forth, becoming the Purusha of a thousand heads, thousand eyes, thousand feet. He (Prajapati) told him, 'you have been from before and so you the Before make this (idam purvah kurushva).'... From the waters indeed was this (universe) born. All this is Brahman Svayambhu (Self-Born).

— Essays On Indo Aryan Mythology by Narayan Aiyangar ('The Tortoise')

In the Taittirtya Aranyaka, the Vātaraśanāḥ Rishis (or Munis, mentioned in RigVeda 10.136 where Shiva also drank poison) are generated by Prajapati who then encounters a tortoise (Kurma) that existed even before he, the creator of the universe, came into being. Aiyangar states that 'the words Vātaraśanāḥ ['girdled by the wind'] and urdhvamanthin ['those who churn upwards']... appear to be the hidden pivot on which the gist of the riddle of the Puranic legend about the churning for nectar turns'.[18]

Atharva Veda

| Arharva | References | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19.53.10[52] | |||

Kāla created living things and, first of all, Prajāpati.

From Kāla self-made Kasyapa, from Kāla Holy Fire was born.— Artharva Veda (translated by R.T.H Griffith, 1895), Book 19, Hymn 53 ('A hymn to Kāma or Time'), Verse 10

Macdonell states that Kurma 'as Kasyapa, often appears beside or identical with Prajapati in the AV [AtharvaVeda]', receiving the epithet svayambhu, meaning 'self-existent' (or 'self-made').[22] Kāla means 'time',[53][54] and in direct relation to creation, the Bhagavata Purana (3.6.1-2) states that Vishnu entered into the inert or static purusha (first principle of creation) to animate it into creation 'with the goddess Kālī [the goddess of time], His external energy, who alone amalgamates all the different elements'.[55] Relating to the Holy Fire, in the Katha Upanishad (1.14-15), Yama, describing the rite of fire and use of bricks to build an altar, states to Nachiketa that fire is the first of the worlds, the foundation of the universe, and the cause of 'acquiring infinite worlds'.[51]

Itihāsa (Epics)

Mahabharata

| Mahabharata | References | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kurma | Book 1: XVIII (18);[56] Book 12: CCCXL (340);[57] Book 13: CXLIX (149)[58] | ||

| Kasyapa | Book 1: XVI (16),[59] XX (20),[60] XXIX-XXXIV (29-34),[61] XLII-XLIII (42-43),[62][63] LXVI (67);[64] Book 3: CXIV (114),[65] CLXXXVIII (188);[66] Book 5: CX (110);[67] Book 6: VI (6);[68] Book 7: LXX (70),[69] Book 12: L (50),[70] CCVII (207),[71] CCVIII (208);[72] Book 13: XVII (17),[73] CLIV (154);[74] Book 14: XVI (16)[75] | 1.29-31 concerns Garuda, son of Kasyapa, seeking the Amrita produced by the churning of the ocean. | |

| Tortoise | Book 1: CXLII (142);[76] Book 3: CLXLVIII (198)[77] Book 6: XXVI (26);[78] Book 9: 54;[79] Book 12: XXI (21),[80] LXXXIII (83),[81] CLXXIV (174),[82] CXCIV (194),[83] CCXLVII (247),[84] CCLXXXVI (286),[85] CCCII (302),[86] CCCXXVII (327);[87] Book 14: XLII (92),[88] XLVI (96)[89] | 3.198 is Akupara, the World-Turtle. Many references are in relation to withdrawing one's senses 'like a tortoise'. | |

| Churning | Book 1: CLXXIII (173);[90] Book 3: CCCIX (309);[91] Book 4: I (1);[92] Book 5: CII (102);[93] Book 12: CCXIV (214),[94] CCXLVI (246),[95] CCCXIX (319),[96] CCCXXX (330),[97] CCCXL (340),[57] CCCXLIII (343),[98] CCCXLIV (344);[99] Book 13: XVII (17),[73] LXXXIV (84),[100] | 5.102 states the churning of the ocean produced a wine called Varuni, the goddess of wine. | |

| Translations are by K.M. Ganguli, unless otherwise stated. | |||

The gods then went to the king of tortoises ['Kurma-raja'] and said to him, 'O Tortoise-king, thou wilt have to hold the mountain on thy back!' The Tortoise-king agreed, and Indra contrived to place the mountain on the former's back. And the gods and the Asuras made of Mandara [Mountain] a churning staff and Vasuki the cord, and set about churning the deep for amrita...

But with the churning still going on, the poison Kalakuta appeared at last. Engulfing the Earth it suddenly blazed up like a fire attended with fumes. And by the scent of the fearful Kalakuta, the three worlds were stupefied. And then Siva, being solicited by Brahman, swallowed that poison for the safety of the creation. The divine Maheswara held it in his throat, and it is said that from that time he is called Nilakantha (blue-throated).— Mahabharata (translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, 1883-1896), Book 1, Astika Parva, Chapter XVIII (18)

Although academics such as N. Sutton state 'there is no indication' that Kurma is an avatar of Vishnu in the Mahabharata,[101] Narayana (i.e. Vishnu) does list the tortoise as one of His incarnations.[57]

Other academics such as M. Vettam have also ascribed the name 'Kurma' to one of the 1,000 serpent-sons of Kadru (daughter of Daksha and one of 13 wives of Kasyapa),[102] although this is actually 'Kumara',[103] which translates to 'Nāga' (snake), 'youth', and 'son'.[104][105] Although Kurma is only briefly mentioned as the pivot for the mountain-churning-rod, there are numerous references throughout to tortoises and churning:

- Tortoises extending and retracting their limbs are mentioned allegorically in regards to drawing in the senses from external objects,[78][80][87] hiding weaknesses,[76] withdrawing desires,[82][88][89] cosmological creation and destruction,[83] reincarnation, and understanding[84]

- Linking to the SamaVeda, The 'ocean of life' is stated to have sorrow for water, anxiety and grief for lakes, disease and death for alligators, heart-striking fears as huge snakes, and tamasic (ignorant or destructive) actions as tortoises[86]

- The 'Vina of melodious notes' of Narada is stated to be made out of a tortoise-shell[79]

- Churning is mentioned throughout - additionally to dairy products such as milk - in regards to producing beauty,[90] notably the sticks and churning staff used by ascetic Brahmins,[91][92] desires generated in the mind,[94] knowledge gained from reading Vedic scriptures,[95][96] karma,[97] authorship of the Mahabharata,[57][99] and cosmological creation and destruction[73][100]

[Narayana to Narada:] I am Vishnu, I am Brahma and I am Sakra, the chief of the gods. I am king Vaisravana, and I am Yama, the lord of the deceased spirits. I am Siva, I am Soma, and I am Kasyapa the lord of the created things. And, O best of regenerate ones, I am he called Dhatri, and he also that is called Vidhatri, and I am Sacrifice embodied.

— Mahabharata (translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, 1883-1896), Book 3, Vana Parva (Markandeya-Samasya Parva), Chapter CLXXXVIII (188)

Kasyapa - synonymous with Kurma - is also mentioned throughout as Prajapati. This includes in relation to the Samudra manthan, most notably in the legend of Garuda, the son of Kasyapa and Vinata (and later the mount of Vishnu), created through sacrificial rituals with the help of Indra and Valikhilya Rishis. While seeking the Amrita produced by the churning of the ocean to free himself and his mother from slavery by Kadru (another wife of Kasyapa) and her 1,000 serpent-sons, Garuda is told by Kasyapa to eat two quarrelling Rishi brothers incarnated as a quarrelling Elephant and Tortoise to gain enough energy. Later, Garuda battles Indra and the celestials and extinguishes a raging fire to obtain the Amrita. In agreement with Indra, Garuda tricks the serpents to achieve freedom without giving them the Amrita; due to licking the drops left behind, the serpents develop forked tongues.[60][61] Other details include:

- Kasyapa, the son of Marichi, is father of the gods and asuras, the 'Father of the worlds'.[64]

- There are two accounts of Kasyapa lifting the Earth out of the waters through sacrifice (after being awarded it by Parasurama) similar to the legend of Varaha. In the first, the Earth is raised as an altar,[65] while in the second the Earth is held on the lap ('uru') of Kasyapa and is given the name 'Urvi'.[70]

- Although given knowledge by Brahma to neutralise poisons,[60] Kasyapa was prevented from saving King Parakshit by a snake called Takshaka disguised as a Brahmin; Takshaka later bit and killed the king.[62][63] The story of Parakshit features in the Bhagavata Purana, where Takshaka is a snake-bird.

- Vamana, the dwarf avatar of Vishnu, is another of Kasyapa's progeny; 'The other wives of Kasyapa gave birth to Gandharvas, horses, birds, kine, Kimpurushas, fishes, and trees and plants. Aditi gave birth to the Adityas'.[71]

- Also known as Tarkshya,[73] Kasyapa cast off his body to pervade the Earth in spirit form and made her rich in abundance.[74]

- Kasyapa encounters an emancipated sage who 'was as unattached to all things as the wind' (e.g. like a Vātaraśanāḥ Muni) and worships him.[75]

Bhagavad Gita

One who is able to withdraw his senses from sense objects, as the tortoise draws its limbs within the shell, is firmly fixed in perfect consciousness.

— Mahabharata (translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, 1883-1896), Book 6, Bhagavad Gita Parva, Chapter XXVI (25) / Bhagavad Gita (translated by Swami Prabhupada), Chapter 2, Verse 58[106]

The same allegory is mentioned frequently throughout the Mahabharata (see above), of which the Bhagavad Gita is a part (Book 6).

Harivamsa

When the gods and Asuras, assembled for (churning) for ambrosia, Vishnu, in the shape of a tortoise in the ocean, held up the Mandara mountain.

— Harivamsha (translated by M.N. Dutt, 1897), Chapter LXXVII (30), verse 41[107]

P. Terry states that 'Probably the oldest sources for the avataras are [the] Harivamsa and Mahabharata', but incorrectly believes Kurma is not listed in the Harivamsa as an avatar of Vishnu (see quote, above).[108] Other details include:

- The allegory of the tortoise drawing in its limbs is mentioned in respect to withdrawing from sense-pleasures (XXX.17)

- Kasyapa is mentioned primarily in regards to creating 'the great Parijata tree' for Aditi to accomplish her vow of Punyaka, the worship of Krishna to obtain a son,[109] resulting in the birth of Vamana, the dwarf avatar (e.g. CXXIV.57).

Ramayana

| Ramayana | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Valmiki version 1 (S. Ayyangar and M.N. Dutt translations): Bala Kanda - XLV (45)[110][111] Valmiki version 2 (H. P. Shastri and R.T.H. Griffith translations): Bala Kanda - 45;[112][113] Adhyatma Ramayana (R.B.L.B Nath translation): Yuddha Kanda - X.47[114] | There are multiple versions of the Ramayana. Many are attributed to Valmiki. |

In former times Rama became a tortoise extending for a hundred thousand yojanas, and at the time of the churning of the ocean bore on his back the golden mountain Sumeru.

— The Adhyatma Ramayana (translated by Rai Bahadur Lala Baij Nath, 1979), Yuddha Kanda, Chapter X, Verse 47

Swami Achuthananda states that although varied like other legends, 'Vishnu's role in the Kurma avatar was limited compared to that in other avatars'.[115] The role of Kurma in the Samudra manthan is essentially the same in all cited versions of the Ramayana, whereby after the mountain-churning-rod begins to sink into the ocean, Vishnu assumes the form of the gigantic tortoise, Kurma, as a pivot to hold it, while in another simultaneous incarnation also helps to turn the rod. Notably, the Adhyatma Ramayana (as quoted above) states Kurma to be an incarnation of Rama. Other details include:

- Kasyapa is mentioned as being awarded the Earth by Parasurama (e.g. Adhyatma Ramayana: Yuddha Kanda: X.51)

- Rama visits the spot where Garuda, a son of Kasyapa and the mount of Vishnu, attempted to eat the warring Elephant and Tortoise (incarnations of quarreling Rishi brothers), but took compassion on the 'Vaikhanasas, Mashas, Valakhilyas, Marichaipas, Ajas, and Dhumras' assembled there and flew away (e.g. Valmiki versions 1 and 2, Aranya Kanda: Chapter 35).[116][117]

Maha-Puranas

J.W. Wilkins states that the 'probable' origin of Kurma is as an incarnation of Prajapati (i.e. Brahma) in the Shatapatha Brahmana (7:5:1:5-7), but as 'the worship of Brahma became less popular, whilst that of Vishnu increased in its attraction, the names, attributes, and works of one deity seem to have been transferred to the other'.[26]

In post-Vedic literature, including the Puranas, Kurma is inextricably linked with the legend of the churning of the Ocean of Milk, known as the Samudra manthan. Kurma is also directly linked with Akupara, the so-called 'world-turtle' that supports the Earth, usually with Sesa.

Agni Purana

| Agni | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2.12-13, 3, 21.2-4 23.12, 46.5-6, 49.1, 50.17, 56, 74.10-11, 74.44-45, 96.30, 98.6, 108.29-30, 123.9, 145.18-31, 213.1-4, 214.5-14, 215.35-37, 219.14-41, 270.3-4, 272.19b-20a, 293.43-46, 315.1-4, 330.18-22[118] |

The celestials who were afflicted by the sighs of the serpent [Vasuki, used as a rope with the Mandara Mountain as a churning rod], were comforted by Hari (Visnu). As the ocean was being churned the mountain being unsupported entered into the water. Then Visnu assumed the form of a tortoise and supported the (Mount) Mandara. From the milky ocean which was being churned, first came out the poison known as Halahala. That poison being retained by Hara (Siva) in his neck, Siva became (known to be) Nilakantha (blue-necked). Then the goddess Varuni (The female energy of the celestial god Varuna), the Parijata (tree) and the Kaustubha (gem) came out of the ocean.

— Agni Purana (unabridged, translated by J. L. Shastri, G. P. Bhatt, N. Gangadharan, 1998), Chapter 3, Verses 7-9

In the Agni Purana, the churning of the ocean of Milk takes place after the curse of the sage Durvasas (on Indra), due to which 'the celestials [Devas] were deprived of all their prosperity' and being defeated by the Asuras, seek refuge with Hari. In this account of the Samudra manthan, poison (Halahala) is generated by the churning which is drunk by Shiva. Vishnu later assumes the form of a 'beautiful damsel' (Mohini) to trick the Asuras into giving away the Ambrosia (Amrita). Requested by Shiva, Vishnu again assumes the Mohini form, causing Shiva to behave 'like a mad man' with lust before 'knowing her as illusory' (3). Focusing on temple construction, prayer, and worship, other details include:

- Kurma is stated to be the second avatar of Vishnu (49.1).

- The Salagrama stone for Kurma is described as black in colour with circular lines and an elevated hinder part (46.5-6)

- Vishnu is stated to reside in Bharata in the form of Kurma (108.29-30) and is presiding deity over Kasyapa, sage of the Vyahrtis (mystical utterances;[119] 215.35.37)

Bhagavata Purana

| Bhagavata | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1.3.16,[120] 2.7.13,[121] 5.9-10,[122][123] 5.18.29-30,[124][125] 8.4.17-24,[126] 8.5.10,[127] 8.7.8,[128] 8.7.10,[129] 10.2.40,[130] 10.40.17-18,[131] 12.13.2[132] | The legend of the Samudra manthan is covered in Canto 8, chapters 5-10. |

In this sixth manvantara millennium, Lord Viṣṇu, the master of the universe, appeared in His partial expansion. He was begotten by Vairāja in the womb of his wife, Devasambhūti, and His name was Ajita. By churning the Ocean of Milk, Ajita produced nectar for the demigods. In the form of a tortoise, He moved here and there, carrying on His back the great mountain known as Mandara.

— Bhagavata Purana (translated by Swami Prabhupada), Canto 8, Chapter 5, Verses 9-10

In the Bhagavata Purana, Kurma is described as an incarnation of Ajita (Sanskrit अजित, meaning 'unsurpassed', 'invincible', and 'undefeated'),[133] a partial expansion of Krishna born to the Saptarishi Vairaja and his wife Devasambhuti during the reign of the sixth Manu, Chakshusha (8.5.9-10).

The churning of the ocean of Milk takes place after the curse of the sage Durvasa (on Indra), due to which 'the three worlds were 'poverty stricken, and therefore ritualistic ceremonies could not be performed'. The Devas seek refuge with Krishna at His abode 'on an island called Svetadvipa, which is situated in the ocean of milk' (Canto 8: Chapter 5). Krishna instructs the Devas to form a pact with the Asuras (led by Bali) to churn the ocean of milk and warns them about the emergence of the poison, Kalakuta. Later, 'observing that most of the demons and demigods had been crushed by the falling of the mountain' to be used as a churning rod, Krishna brings them back to life, lifts the Mandara mountain, and carries it on the back of Garuda to the Ocean of Milk (Canto 8: Chapter 6). The Ocean is churned with Vasuki as a rope, the sleepy Kurma as the base who 'extended for eight hundred thousand miles like a large island' and felt a 'pleasing sensation' at being scratched, and Ajita Himself personally helping. Poison is generated, to which Shiva 'compassionately took the whole quantity of poison in his palm and drank it' as an example of voluntary suffering for others; the remaining poison was drunk by animals with poisonous bites such as scorpions and Cobras (Canto 8: Chapter 7).

Churned with a renewed vigor by 'the sons of Kasyapa', the Ocean of Milk produces auspicious beings, including Lakshmi and Dhanvantari - 'a plenary portion of a plenary portion of Lord Visnu' - with the nectar of immortality (Amrita; Canto 8: Chapter 8). After the demons steal the nectar, Vishnu incarnates as Mohini-Murti, who despite warning the lustful and infatuated demons not to trust Her, is still given the Amrita which She distributes to the Devas (Canto 8: Chapter 9). Vishnu leaves and a battle ensues between the Devas and Asuras. On the cusp of defeat, the Devas appeal to Vishnu for help once again, who reappears and helps to defeat the Asuras (Canto 8: Chapter 10). Other details include:

- Kurma is listed as the 10th and 11th incarnations of Krishna (1.3.16 and 2.7.13)

- Vishnu is stated to live in the form of a tortoise (kūrma-śarīra) in a land called Hiraṇmaya-varṣa[134] (5.18.29)

- Kurma is described as 'the reservoir of all transcendental qualities, and being entirely untinged by matter... [is] perfectly situated in pure goodness' (5.18.30)

- Relating to the tortoise symbollsing the sun it is stated that the 'sun-god marks the path of liberation' (8.5.36)[135]

- Vishnu invigorates the Devas with Sattva (goodness), the Asuras with Rajas (passion), and Vasuki with Tamas (ignorance), according to their natures (8.7.11)[136]

When the Supreme Personality of Godhead appeared as Lord Kūrma, a tortoise, His back was scratched by the sharp-edged stones lying on massive, whirling Mount Mandara, and this scratching made the Lord sleepy. May you all be protected by the winds caused by the Lord’s breathing in this sleepy condition. Ever since that time, even up to the present day, the ocean tides have imitated the Lord’s inhalation and exhalation by piously coming in and going out.

— Bhagavata Purana (translated by Swami Prabhupada), Canto 12, Chapter 13, Verse 2

Brahma Purana

| Brahma | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1.120-127, 1.164-165, 1.217-218, 10.39-46, 16.57, 69.176; Gautami-Mahatmya: 4.48, 42.4-7, 52.68-73[137] |

Devas and Asuras after mutual consultation came to an agreement that they should churn the ocean. O Mahesa, while they were churning there merged Kalakuta (a virulent poison). Excepting you [Shiva] who else could have been competent to swallow it?

— Brahma Purana (unknown translator, 1955), Gautami-Mahatmya, Chapter 42, Verses 4-7

As quoted above, the legend of Kurma is only briefly mentioned in the Brahma Purana, although it is stated that the 'Devas were not able to conquer Danavas in battle' before Shiva in this account of the Samudra manthan - not Narayana/Vishnu - is approached for help (Gautami-Mahatmya: 42.3). Kurma is however mentioned in prayers and obeisances throughout, such as by Kandu (69.176) and Indra (Gautami-Mahatmya: 4.48). Other details include:

Brahmanda Purana

| Brahmanda | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Part 2: (Kasyapa) 1.53.54, 1.119-124a, 3.56, 3.65-69a, 3.84, 3.104-106;[138] Part 3: (Tortoise) 68.96; (Kasyapa) 47.60-61, 71.238; [139] Part 4: 9-10, 29.91-92[140] | No notable mentions in parts 1 or 5[141][142] |

In the middle of the ocean of Milk, the exceedingly lustrous lord in the form of [the] Primordial Tortoise became the basis and support of the Mandara mountain that was rotating therein. Madhava pulled Vasuki [used as a cord or rope] speedily in the midst of all Devas by assuming a separate form and from the midst of Daityas by assuming another form. In the form of Brahma (KSrma - Tortoise...) he supported the mountain that had occupied the ocean. In another form, that of the divine sage (i.e Narayana), he enlivened Devas and rendered them more powerful and robust frequently with great brilliance.

— Brahmanda Purana (translated by G.V.Tagare, 1958), Part 4, Chapter 9, Verses 60-65

In the Brahmanda Purana, the churning of the ocean of Milk takes place after Brahma curses Indra for killing the powerful Asura ascetic Visvarupa, the grandson of Kasyapa (and potential challenger to his position). The curse causes ruin to the Earth and to the Brahmins (who become covetous and atheistic), while the weakened Devas are attacked by the Asuras and forced forced to flee to Narayana for refuge. In this account of the Samudra manthan, no poison is produced or consumed by Shiva, and it is stated that the Daityas became known as 'Asuras' due to rejecting Varuni, the goddess of wine, after her emergence from the ocean ('a-sura' meaning 'without sura', or alcohol; Part 4: 9). Notably, the manifestation of the Mohini avatar of Vishnu during the battle between the Devas and Asuras over the nectar (Amrita) is stated to be identical in form to the goddess Mahesvari (Part 4: 10).

Brahmavaivarta Purana

| Brahmavaivarta | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Brahma Khanda: XXVI.91-104, XXX.1-10; Prakriti-Khanda: XXXIV, XXXVIII, 39; Ganapati Khanda: 31; Krsna-Janma Khanda: 6, 21, 22, 46, 55, 73, 87, 129[143][144] | Roman numerals indicate the Nath translation; numerical digits indicate the Nager translation (two parts), which does not provide verse numbers (some pages of the Nath translation are also missing verse numbers). |

...lord Hari directed Brahma to churn the above sea [the Ocean of Milk or 'ksiroda sea'] with a view to discover the celestial goddess of fortune [Lakshmi] and to restore her to the gods... After a long time, the gods arrived at the margin of the sea. The Mandar Mountain they made as their churning pole, the tortoise god as their basin or cup, the god Ananta as their churning rope. In this way they began to churn the ocean...

— Brahmavaivarta Purana (translated by R.N. Sen, 1920), Prakriti Khanda, XXXVIII (38), Verses 51-55

In the Brahmavaivarta Purana, two accounts of Kurma relating to the Samudra manthan are given. In the first, the churning of the ocean of Milk takes place after Indra is cursed by the sage Durvasa for arrogance, resulting in the gods and the people of Earth being 'deprived of their glory' (Prakriti-Khanda: 36/XXXVI). The account of the churning itself consists of only a few verses, without mention of the emergence of poison or the appearance of the Mohini avatar (38/XXXVIII).

In the second account, Sanatkumara encounters Kurma at the ocean of milk after the churning took place, where the 'vast tortoise of the size of a hundred Yojanas was lying there. He looked terrified, shaking, grief-stricken and dry' due to being driven out from the water by a fish called Raghava, an epithet usually associated with the Rama avatar (Krsna-Janma Khanda: 87).

Kurma is also mentioned repeatedly as the support of the Earth along with the Naga Sesa or Ananta. Generally, it is stated that the Earth rests on the head or hood of a Naga, the Naga rests on the head of Kurma, and Kurma is supported by the Wind (Vayu) at the command of or supported itself by Krishna (Prakriti Khanda: XXXIV, Ganapati Khanda: 31, and Krsna-Janma Khanda: 6, 21, 22, 29, 46, 55, and 73). There are variations, such as where the air supports water which supports Kurma (Prakriti Khanda: XXXIV). In these accounts, Krishna is stated to take the form of a tortoise from his amsha (part)[145] and in the form of Sesa carries the entire universe on His head (Krsna-Janma Khanda: 22); Sesa states he is also from the amsha of Krishna, rests on the head of Kurma 'like a small mosquito on the elephant head', and that there are 'innumerable' Brahmas, Vishnus, Shivas, Sesas, and Earth-globes beside the tortoise (i.e. a Multiverse; Krsna-Janma Khanda: 29). Other details include:

- A worship ritual is described including the worship of Kurma in a 'triangular mandala' (i.e. a symbol; Brahma Khanda: XXVI.91-104)

- It is stated 'As a gnat mounts the back of the elephant, so this god [Ananta] is mounted on the back of Kurma (tortoise). This kurma is a digit of the digits of Krisna' (Brahma Khanda: XXX.1-10)

Garuda Purana

| Gaurda | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Part 1: 1.24, 15, 28.5, 32.18, 53.1, 86.10-11, 114.15, 126.3, 142.2-3, 143.2-4;[146] Part 2: 194.13, 196.9, 234.24;[147] Part 3: 30.37, 32.45; Brahma Moska Kanda: 15, 24.89, 26.14-15 [148] | Part 3 (Brahma Moska Kanda) 1.51-52 classifies Puranas. |

Taking the form of a Tortoise he [Vishnu] lifted the mountain Mandara on his back for the benefit of all. At the time of churning the milky ocean, he took the form of the first physician Dhanvantari and holding the vessel full of Nectar rose up from the ocean. He taught the science of medicine and health with its eightfold sub-divisions to Susruta. Hari took the form of a lady [i.e. Mohini] and made devas drink nectar.

— Garuda Purana (translated by 'a board of scholars', 1957), Part 1, Chapter 142, Verses 2-5

In the Garuda Purana, two accounts of Kurma relating to the Samudra manthan are given, both of which are brief and almost identical (Part 1: 142.2-5 and Part 3: 15.16-18). Notably, the second account explicitly names the 'pretty damsel' ('lady' in the first) as Mohini, and is itself within a chapter that lists other avatars of Vishnu to include prince Sanandana and Mahidasa, expounder of the Pancaratra philosophy. Other details include:

- Kurma is stated to be the 11th overall incarnation of Vishnu (Part 1: 1.24), and the second of His ten primary avatars (Dashavatara; Part 1: 86.10-11 and Part 3: 30.37)

- 'Kurma' is one of the thousand names (Sahasranama) of Vishnu (Part 1: 15)

- Relating to sacred rites (Vratas). 'In the middle [of the mystical diagram] the Adharasakti (the supporting power), Kurma (the tortoise) and Ananta (Lord Visnu's serpent bed) should be worshipped' (Part 1: 126.3)

- Kurma is associated with the south-west (196.9); Vishnu 'the base' (of all) as well as Ananta and Kurma (Part 2: 234.24)

- Relating to the support of existence, it is stated that 'Above the pedestal, to Laksmi called Sakti, the support of the universe. Above the pedestal, to Vayu and Kurma. Above that to Sesa and Kurma' (Part 3: Brahma Moska Kanda: 24.89)

Kurma Purana

| Kurma | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1; (Kasyapa) 15.5-15; Krishna: 25.67-73[149] | Kurma is the narrator of this Purana. 15.5-15 names the 13 daughters of Daksha given to Kasyapa as wives to be Aditi, Diti, Arista, Surasa, Surabhu, Vinata, Tamra, Krodhavasa, Ira, Kadru and Muni. |

In the past the Gods together with the Daityas and Danavas churned the Ocean of Milk for the sake of nectar by using the Mandara (mountain) as the churning rod. At that time lord Visnu, the slayer of Jana in the form of a Tortoise held the Mandara (mountain) for the purpose of rendering benefit to the Gods. On seeing the indestructible lord Vishnu in the form of a Tortoise, the Gods and the great sages headed by Narada were also highly pleased. In the meantime (out of the Ocean) came out Goddess Sri (Laksmi) the beloved of Narayana; and lord Visnu, Parusottama, betook her (as his spouse).

— Kurma Purana (translated by A.S. Gupta, 1972), Part 1, Chapter 1, Verses 27-29

The translator, Gupta, states in the introduction that the Kurma Purana is named as such 'because is was narrated by Kurma first to Indrayumna and then to the sages and the gods'. Otherwise, this Purana does not seem to elaborate or expand on the legend or characteristics of the Kurma avatar or Kasyapa. However, notably, there is an account of Brahma travelling across the waters and to his surprise encountering Krishna, which seems to parallel the account of Prajapati encountering the Tortoise in the Taittirtya Aranyaka (relating to the Black YajurVeda, see above).

Linga Purana

| Linga | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Part 1: 8.58-26, 8.63-67, 55.58-61, 63.22b-26, 67.15-24, ;[150] Part 2: 17.37-38, 24.21, 48.30-32, 96.17-22, 96.46-50, 98[151] | Part 2 continues up to chapter 108 and then starts at chapter 1 again. |

O lord Visnu, you have incarnated for the happiness of the world... You held aloft the Mandara mountain in the form of a tortoise...

— Linga Purana (translated by J.L.Shastri), Part 2 Chapter 96, Verses 17-22

It seems that the Linga Purana does not relate the legend of Samudra manthan, although a brief mention is made, as quoted above. Other details include:

- Kurma is mentioned as the seat of Shiva in ritual worship (Part 2: 24.21), and it is stated that the skull of Kurma is strung on the necklace of Shiva (Part 2: 96.46-50)

- Kurma is one of the 10 primary avatars of Vishnu (Dashavatara) for the good of the world; other avatars are due to the curse of Bhrgu (Part 2: 48.30-32)

Markandeya Purana

| Markandeya | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| XXXIX.31-35, XLVII.7, LIII, LIV.31, LXVIII.21, LXVIII.23[152] |

It seems that the Markandeya Purana does not relate the legend of Samudra manthan, although the Kurma incarnation of Vishnu is briefly mentioned (XLVII.7), and an entire chapter is dedicated to describing the lands and people related to Kurma, as narrated by the sage Markandeya (LIII). Other details include:

- It is stated 'Like a tortoise withdrawing its limbs, he, who, restraining his desires, lives with his mind centered in the souls, sees the Divine soul in the human soul' (XXXIX.31-35) and 'Even as the tortoise withdraws unto itself all its lines, so having drawn unto him people's hearts, he himself exists with his own mind perfectly restrained' (LXVIII.23)

- Vishnu resides in Bharata as the tortoise (LIV.31)

- It is stated 'The man, who is looked on by the Nidhi the Kacchapa (tortoise), becomes possessed of the quality of Tamas' (LXVIII.21)

Matsya Purana

| Matsya | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| X.6-7, XLVII.41-45, LIV.15, XCIII.124, CCXV.67-68, CCXLVI.53-65, CCXLIX-CCLI, [153] |

...the turtle [Kurma] said - "When I can easily hold all the three regions on my back, how can I feel the weight of this Mandara mountain?" Sesa said "I can coil round the three regions what difficulty can therefore be in my coiling round this Mandara mountain?" Afterwards all the Devas and the demons hurled Manarachala into the milk-ocean, after which Sesa coiled round it, and Kurma (turtle) placed Himself underneath it as the support of the mountain...

When all the Devas and the demons were overcome with fatigue in churning the ocean, Indra caused the rains and cool wind to refresh them. But, in spite of all that when the Lord Brahma found them giving way to fatigue, He shouted out "Go on churning. Those who persevere are undoubtedly blessed with the highest prosperity".— Matsya Purana (translated by A. Taluqdar, 1916), Chapter CCXLIX (249), Verses 25-36 and 55-57

The Matsya Purana dedicates several chapters to the legend of the Samudra manthan, which itself contains several notable variances. In this account, the Daityas led by Bali repeatedly defeat the Devas led by Indra due to being resurrected by the sage Sukra (son of Bhrgu) when killed, using a mantra provided by Shiva. Advised by Brahma, the Devas secure an alliance with Bali in Patala, the agreement of Mandarachala (king of the mountains) to be used as a churning rod, and the agreement of Sesa and Kurma - said to be 'endowed with 1/4 of Vishnu's power... to support the Earth' - as the rope and base of the churning rod, respectively. Unable the churn the Ocean of Milk by themselves, the Devas and Asuras approach Vishnu 'absorbed in deep meditation' in Vaikuntha for help, who agrees (CCXLIX).

After producing several auspicious items (e.g. the Kaustubha Gem) and beings (e.g. Lakshmi), several 'venomous insects and terrible beings' are produced along with 'hundreds of poisonous things' such as Halahala, before the emergence of a powerful poison-being called Kalakuta that wishes to destroy both the Devas and Demons. After challenging them to either swallow him or 'go to Lord Shiva', the latter is approached and swallows the poison-being before returning to his abode (CCL). The Ocean of Milk being churned once again produces more auspicious beings and items, including Dhanvantari with the nectar of immortality (Amrita), before Vishnu 'assumes the form of a bewitching damsel' (Mohini) to take the nectar from the Asuras and give it to the Devas. The Asuras are then destroyed by Vishnu in battle using His 'terrible Chakra' (CCLI). Other details include:

- The Samudra manthan is stated to have taken place in the fourth of twelve wars between the Devas and Asuras (XLVII.41-45)

- A verse of a mantra referencing Kurma is related to the throat and the feet (LIV.15)

- It is stated 'He should guard his limbs of body and keep them secret just as a tortoise' (CCXV.67-68)

Narada Purana

| Narada | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Part 1: 2.37, 10.3-4;[154] Part 2: 44.26b-28a, 50.89-91, 54.11, 56.739b-745, 59.36, 62.53;[155] Part 3: 82.6-7, 89;[156] Part 4: 119.14-19, Uttara Bhaga: 8.7-11;[157] Part 5: Uttara Bhaga: 52.29b-35, 68.4[158] | The Narada Purana focuses on worship and rituals. |

It was this [Mandara] mountain that was formerly lifted up by Hari (in the form of [the] Divine Tortoise) and used for churning (the milk ocean) by the Devas and Danavas. Sindhu (the ocean) which extends to six hundred thousand Yojanas is the deep pit made by this mountain. This great mountain was not broken even when it rubbed against the physical body of the Divine Tortoise. O leading king, when it fell into the ocean all the hidden parts of the ocean were exposed by the mountain. O Brahmanas, water gushed out from this mountain [and] went up through the path of the Brahmanda (Cosmic Egg). Great fire was generated by this mountain due to attrition when it came into contact with the bony shell of the (Divine) Tortoise... It was for a great period of time viz. ten thousand years than this mountain ground and rubbed the armlets of the discus-bearing Lord.

— Narada Purana (unknown translator), Part 4, Uttara Bhaga, Chapter 8, Verses 7-8 and 11

In the Narada Purana, a brief synopsis of the Samudra manthan is given by Brahma to Mohini, as quoted above (Part 4: 8.7-11). There are two other notable mentions of this legend. The first is by Saunaka who said 'When there was an impediment at the time of churning the ocean for the sake of nectar, he [Kurma] held the mount Mandara on his back, for the welfare of the gods. I seek refuge in that Tortoise' (Part 1: 2.37). In the second, it is stated 'it was when the milk-ocean was churning that Kamoda was born among the four jewels of Virgins' (Part 5: Uttara Bhaga: 68.4). Other details include:

- Several allegories of the tortoise drawing in its limbs are given, including in relation to the creation and withdrawal of living beings (Part 2: 44.26b-28a) and withdrawing the sense organs (Part 2: 50.89-91, and 59.36)

- The division of the Earth - Kurma-vibhaga - is in relation to the Jyotisa, an auxiliary text of the Vedas (Part 2: 54.11 and 56.739b-745)

- Kurma is one of the ten primary avatars (Dashavatara) of Vishnu (Part 4: 119.14-19)

Padma Purana

| Padma | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Part 1: 3.25b-29, 4, 5.81-87, 13.146b, 13.180, 13.186, 14.22-27;[159] Part 2: 41.38-44a, 47.77-78, 47.85, b-8649.120-122a, 53.3, 75.90;[160] Part 5: 8-10;[161] Part 6: 78.28-43;[162] Part 7: 5.12-20, 30.11-15, 66.44-54, 71.23-29b, 71.169-188, 71.244-264, 78.16-29;[163] Part 8: 97.6b-8, 120.51b-73;[164] Part 9: 228.19-24, 229.40-44, 230.3-11, 231-232, 237.15-19;[165] Part 10: 6.175-190, 11.80-89, 11.92b-101, 17.103-117[166] | No notable mentions in parts 3 or 4[167][168] |

Visnu himself, remaining in the ocean in the form of a tortoise, nourished the gods with unusual lustre... the goddess Varuni became (manifest), Her eyes were rolling about due to intoxication... [she said:] "I am a goddess giving strength. The demons may take me". Regarding Varuni as impure, the gods let her go. Then the demons took her. She became wine after being taken (by them)... Then the deadly poison (came up). By it all gods and demons with (other) deities were afflicted. Mahadeva [Shiva] took and drank that poison at his will. Due to drinking it Mahadeva had his throat turned dark blue. The Nagas drank the remaining poison that had come up from the White [Milky] Ocean.

— Padma Purana (translated by N.A. Deshpande, 1988), Part 1, Chapter 4, Verses 41-56

In the Padma Purana three accounts of the Samudra manthan are given, all beginning with Indra being cursed by Durvasas for arrogance. In the first, narrated by Pulastya, as a result of the curse the 'three worlds, along with Indra, were void of affluence... [and] the Daityas (sons of Diti) and Danavas (sons of Danu) started military operations against [the] gods', forcing them to seek refuge with Vishnu. Vasuki is used as a rope to churn the ocean. Notably, during the churning, Varuni (Goddess of Wine) is upon emerging rejected by the gods and accepted by the Asuras, the opposite of the account given in the Brahmanda Purana (to explain the meaning of 'Asura'). Unnamed poison also emerges which is drunk by Shiva, before the emergence of Dhanvantari with the nectar of immortality (Amrita) as well as Lakshmi. Although the Asuras take the nectar, Vishnu assumes the form of Mohini to trick them and give it to the gods. The Asuras are destroyed, with the Danavas since then becoming 'eager for (the company of) ladies' (Part 1: 4).

O gods, Indira (i.e. Laksmi), due to whose mere glance the world is endowed with glory, has vanished due to the curse of the Brahmana (viz. Durvasas). Then, O gods, all of you, along with the demons, having uprooted the golden mountain Mandara and making it, with the king of serpents going round it, the churning-rod, churn the milky ocean. O gods, from it Laksmi, the mother of the world will spring up. O glorious ones, there is no doubt that because of her you will be delighted. I myself, in the form of a tortoise, shall fully hold the (Mandara) mountain (on my back).

— Padma Purana (translated by N.A. Deshpande, 1988), Part 5, Chapter 8, Verses 19b-23

In the second account, narrated by Suta, as a result of the curse the 'mother of the worlds' (Lakshmi) disappears, and the world is ruined by drought and famine, forcing the gods - oppressed by hunger and thirst - to seek refuge with Vishnu at the shore of the Milky Ocean (Part 5: 8). Ananta (Vasuki in the first account) is used as a churning rope. On Ekadashi day, the poison Kalakuta emerges, which is swallowed by Shiva 'meditating upon Vishnu in his heart'. An evil being called Alaksmi (i.e. a-Laksmi or 'not Laksmi') them emerges and is told to reside in places such as where there is quarrel, gambling, adultery, theft, and so forth (Part 5: 9). The churning continues and auspicious beings and items emerge, including 'the brother of Laksmi, [who] sprang up with nectar. (So also) Tulasi [i.e. Lakshmi], Visnu's wife'. On this occasion, Vishnu assumes the form of Mohini merely to distribute the nectar amongst the gods, without mention of tricking the Asuras (Part 5: 10).

The third account, narrated by Shiva, is very similar to the others except with a far greater emphasis on Lakshmi, and although the poison Kalakuta emerges and is swallowed by Shiva, there is no mention of Alaksmi or the Mohini avatar (Part 9: 231-232). The Naga used as a rope for churning is referred to as 'the Lord of the Serpents' (likely Ananta). Other details include:

- Kurma is mentioned as an avatar of Vishnu (Part 1: 3.25b-29), as a giver of boons (Part 1: 5.81-87), and is stated to have appeared during the fourth war between the Devas and Asuras (Part 1: 13.180); during the churning, Indra is stated to have vanquished Prahlada (Part 1: 13.186)

- Relating to Kurma as the world-turtle, it is stated 'Due to truth (alone), the sun rises; also the wind blows; the ocean would (i.e. does) not cross its boundary nor would (i.e. does) the Tortoise avert (sustaining) the earth' (Part 2: 53.3); Kurma is also mentioned as the 'first tortoise', the prop of everything, cause of production of ambrosia, and the support of the Earth (Part 7: 71.169-188); finally, after raising the earth from the waters in the form of a boar (Varaha), it is stated that Vishnu placed it on the head of Sesa before taking the form of Kurma (Part 9: 237.15-19)

- Kurma is named as one of the 10 primary avatars (Dashavatara) of Vishnu by Yama (Part 7: 66.44-54), Brahma (Part 7: 71.23-29b), and Shiva (Part 9: 229.40-44)

- The salagrama of Kurma is described as 'raised, round on the surface, and is filled with a disc (like figure). Marked with Kaustubha, it has a green colour' (Part 8: 20.51b-73)

- Kurma is stated to reside in Vaikuntha (Part 9: 228.19-24); and is one of the 108 names of Vishnu (Part 10: 17.103-117)

- Shiva gives salutations to Kurma, who 'extracted the Earth along with mountains, forests and groves, from inside the water of the deep ocean' (Part 10: 6.175-190)

Shiva Purana

| Shiva | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Part 2: 1.44-45, 16.5;[169] Part 3: 11.19, 11.49-50, 16, 22;[170] Part 4: 4.53, 10.38, 31.134-136, 37.35-39[171] | Nothing notable in part 1[172] |

In the Shiva Purana, neither of the two accounts of the Samudra manthan mention Kurma. Poison is generated by the churning in both accounts, although only in the first account is Shiva stated to have drank it (Part 3: 16). The second mentions the Mohini avatar of Vishnu incarnating at the 'behest of Siva' (Part 3: 22). Other details include:

- It stated that 'On account of the [sexual] alliance of Siva and Parvati, the earth quaked with the weight along with Sesa (the serpent) and Kacchapa (the tortoise [i.e. Kurma]). By the weight of Kacchapa, the cosmic air, the support of everything, was stunned and the three worlds became terrified and agitated' (Part 2: 1.44-45); Kurma supports the Earth (Part 3: 11.19)

- The skull of Kurma is stated to be in the necklace of Shiva (Part 3: 11.49-50)

- Kurma is named as one of the 10 primary avatars (Dashavatara) of Vishnu (Part 4: 31.134-136)

- One of the ten 'vital breaths' (prana or Vayu) is called 'Kurma' (Part 4: 37.35-36) and is stated to be for 'the activity of closing the eyes' (Part 4: 37.39; the Agni Purana states it to be for opening the eyes)

Skanda Purana

| Skanda | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Part 1: 8.89, 9-12;[173] Part 2: 47.12-15;[174] Part 3: Uttarardha: 11.8-11;[175] Part 4: Venkatacala Mahatmya: 11, 20.81, 36.20-26;[176] Part 5: Purusottama-Ksetra Mahatmya: 15.30, 22.32-43;[177] Part 6: Margasirsa Mahatmya: 3.23-29;[178] Part 7: Vasudeva-Mamatmya: 9-14, 18.12-20, 27.32-33;[179] Part 8: Setu Mahatmya: 3.81-82, 37.15-20, 46.31-36;[180] Part 9: Dharmaranya Khanda: 19.16, 20.20-23;[181] Part 10: Purvardha: 8.100, 29.17-168, 32.69-71, 41.102, 50;[182] Part 11: Uttarardha: 51, 70.69;[183] Part 12: Avantiksetra Mahatmya: 42.12-14, 44 63.83;[184] Part 14: Reva Khanda: 7;[185] Part 15: Reva Khanda: 151.1-17, 181.56-65, 182.1-22;[186] Part 17: Nagara Khanda: 144.117;[187] Part 18: Nagara Khanda: 210, 262.21-22, 271.245-455;[188] Part 19: Prabhasa-Ksetra Mahatmya: 7.17-37, 11.18, 32.100-103a, 81.23-24;[189] Part 20: Prabhasa Khanda: 167.33, 199.11-12[190] | Nothing notable in parts 13 or 16.[191][192] Part 15 relates that Hamsa, one of Kasyapa's sons, became the mount of Brahma (221.1-6) |

As the Ocean of Milk was being churned, the mountain sank deep into Rasatala. At that very instant, the Lord of Rama, Visnu, became a tortoise and lifted it up. That was something really marvellous... The excellent mountain had adamantine strength. It rolled on the back, neck, thighs, and space between the knees of the noble-souled tortoise. Due to the friction of these two, submarine [i.e. underwater] fire was generated.

— Skanda Purana (Unknown translator, 1951), Part 1, Chapter 9, Verses 86 and 91

In the Skanda Purana four accounts of the Samudra manthan are given. In the first, the churning of the ocean of Milk takes place after Indra is cursed by the sage Brhaspati, resulting in the disappearance of Lakshmi, misery to all, and ruin of the Devas, defeated in battle by the Asuras who take their precious items such as gems to Patala. On the advice of Brahma, Indra and the Devas make a pact with Bali, leader of Asuras, to recover the gems from the Ocean of Milk. Unable to move the Mandara mountain to use as a churning rod, Vishnu is asked for help, who arrives on Garuda, takes the mountain to the ocean, and incarnates as Kurma. Vasuki is used as the churning rope. The Kalakuta poison generated envelopes the Devas and Daityas - causing ignorance and lust - before enveloping all existence (including Vaikuntha) and reducing the cosmic egg to ash (Part 1: 9). Shiva is approached for refuge, and the origin and need to worship Ganesha to 'achieve success in undertaking' is explained before Shiva drinks the poison (Part 1: 10). More information on Ganesha-worship is given before the churning resumes, producing many auspicious items and beings, including Lakshmi (Part 1: 11). Dhanvantari emerges with the nectar of immortality (Amrita), which is taken by the Asuras. Vishnu incarnates as Mohini, and despite warning Bali that 'Women should never be trusted by a wise man' is still given the nectar which She gives to the Devas (Part 1: 12).

In the second account, Indra is again cursed by the sage Brhaspati (Part 7: 8), resulting in the disappearance of Laksmi, and with her, an absence of 'Penance, Purity, Mercy, Truth... True Dharma, Prosperity... Strength [and] Sattva (quality of goodness)'. Hunger, poverty, anger, lust, flesh-eating, and perverse-thinking abound, including belief that adharma is dharma, and perverse interpretations of the Vedas to justify killing animals (Part 7: 9). Vishnu is approached for refuge by the Devas and instructs them to churn the Ocean of Milk (Part 7: 10). Indra forms a pact with the Asuras, Sesa is used as a churning rope with the Mandara Mountain, and Vishnu incarnates as Kurma as the base. After a thousand years of churning the poison Halahala is generated and swallowed by Shiva; the drops that fell are taken by serpents, scorpions, and some medicinal plants (Part 7: 11). The churning continues for another thousand years, producing auspicious items and beings, including Laksmi (Part 7: 12). Dhanvantari emerges with the pitcher of Amrita which is taken by the Asuras, and Vishnu assumes 'a marvellously beautiful feminine form that enchanted all the world' (Mohini). Despite warning the Asuras not to trust her, Mohini is given the Amrita which is handed to the Devas before the Asuras are destroyed in battle (Part 7: 13).

In the third brief account, the churning takes place after 'a great loss of gems due to wicked souls' and the loss of righteousness. Vasuki is used as the churning cord as the Devas and Asuras 'placed the main plant of activity on the back of the (divine) tortoise and churned out the precious gems'. Many auspicious items and beings are generated, including Sura (alcohol; in other accounts Varuni) and Dhanvantari. Quarreling ensues between the Devas and Asuras, and Vishnu incarnates as 'the fascinating form of a woman' (Mohini) to beguile the demons as Indra gives them the Sura and via 'slight of hand' takes the Amrita. Halahala poison is also generated which is consumed by Shiva (Part 12: 44).

In the fourth account, the legend is briefly retold by Visvamitra. The details are much the same as the previous accounts, with Vasuki as the cord as the 'Kacchapa (Tortoise incarnation of Visnu) held up (the mountain)', including the Kalakuta poison drunk by Shiva and the incarnation of Mohini to trick the Asuras. The notable exception is that the churning first produces a 'hideous' family of three of Ratnas (jewels); rejected by both the Devas and Danavas, they are accepted by Ka (i.e. Brahma; Part 18: 210).

Notably, reminiscent the account of Prajapati and the Tortoise in the Taittiriya Aranyaka (see above), there is also an account, during the time of the universal dissolution, when Brahma 'assumed the form of a Khadyota (Firefly, Glow-worm)' and moved about for a thousand divine years before finding 'the Lord [Vishnu] asleep in the form of a tortoise'. Woken by Brahma, Vishnu 'got up ejecting the three worlds that had been swallowed at the time of the close of the [previous] Kalpa' with all creation - including the Devas, Danavas, moon, sun, and planets - being generated from and by Him. Vishnu also sees the Earth 'was in the great ocean perched on the back of the tortoise' (Part 14: Reva Khanda: 7). Other details include:

- Kurma is mentioned to have held the Mandara Mountain (Part 1: 8.89);

- After being resorted to by Tara and 'Permeated by her, Kurma, the sire of the universe, lifted up the Vedas' (Part 2: 47.12-15)

- Exploring the Linga of Shiva, 'The primordial Tortoise that was stationed as the bulbous root of the Golden Mountain as well as its support was seen by Acyuta [Vishnu]'; It is also by Shiva's blessing that Sesa, Kurma, and others are capable of bearing the burden of that Linga (Part 3: Uttarardha: 11.8-11)

- After Varaha lifted the earth out of the waters, Vishnu 'placed the Elephants of the Quarters, the King of Serpents and the Tortoise for giving her extra support. That receptacle of Mercy (Hari) willingly applied his own Sakti (power) in an unmanifest form as a support for them all' (Part 4: Venkatacala Mahatmya: 36.20-26); Bhrgu also states Kurma supports the earth (Part 15: Reva-Khanda: 182.1-22); and Sesa and Kurma are also later stated to stabilise the Earth (Part 17: Nagara Khanda: 144.117)

- Kurma is mentioned where Vishnu is stated to be the annihilator in the form of Rudra (Part 5: Purusottama-Ksetra Mahatmya: 22.32-43)

- Kurma is named as one of 12 incarnations of Vishnu, who states to Brahma:

When the sons of Kasyapa (i.e. Devas and Asuras) will churn the ocean for (obtaining) nectar, I [Vishnu], assuming the form of a tortoise, will bear on my back Mount Mandara used as the churning rod.

— Skanda Purana (Unknown translator, 1951), Part 7, Chapter 18, Verses 12-20

- In the procedure for Puja Mandala construction, Matsya and Kurma should be installed in the South-West and depicted as animals below the waist but in human form above (Part 7: Vasudeva-Mamatmya: 27.32-33)

- It is stated that the Linga of Shiva evolved from 'the back of a tortoise (shell)' (Part 9: Dharmaranya Khanda: 19.16) and that 'The Bija [origin] of Vahni (Fire) is accompanied by (the seed of) Vata (Wind) and the Bija of Kurma (tortoise)' (Part 9: Dharmaranya Khanda: 20.20-23)

- It is stated that 'Like a tortoise that withdraws all its limbs, he who withdraws the sense-organs though the proper procedure of Pratyahara shall become free from sins' (Part 10: Purvardha: 41.102)

- Kumari - the Shakti of Kurma - has a noose in her hand and is located to the south of Mahalaksmi (Part 11: Uttarardha: 70.69)

- 'Kurma' is one of the thousand names (Vishnu Sahasranama) of Vishnu (Part 12: Avantiksetra Mahatmya: 63.83)

- Kurma is listed in the Dashavatara, or ten primary incarnations of Vishnu (Part 15: Reva-Khanda, 151.1-7)

- Bhrgu refers to a Ksetra (temple) that stands on Kaccapa (i.e. a tortoise) and states there will be a city named after Him, Bhrgukaccha (Part 15: Reva-Khanda: 182.1-22)

- The star constellations in the form of Kurma (i.e. the tortoise) are discussed, where it is also stated Kurma is stationed in Bharata and faces the east (Part 19: Prabhasa-Ksetra Mahatmya: 7.17-37 and 11.18)

- A Holy spot called Prabhasa in Bharata is located to the south-west of the shrine of Kurma (Part 20: Prabhasa Khanda: 167.33)

Varaha Purana

| Varaha | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Part 1: 4.2-3, 8.43, 12.10, 40, 41.46-48, 48.17, 55.36-39, 113.21, 113.42;[193] Part 2: 163.35, 211.69[194] |

...[Kurmadvadasivrata: In] the month of Pausa (Makara) amrta was churned from the ocean, and then lord Visnu, on his own accord, became a Kurma (tortoise). The tithi Dasami on the bright half of this month is assigned to Visnu in the Kurma form.

— Varaha Purana (Unknown translator, 1960), Part 1, Chapter 40, Verses 1-2

In the Varaha Purana, the legend of Samudra manthan is only briefly mentioned, as quoted above. Other details include:

- Kurma is one of the 10 primary avatars (Dashavatara) of Vishnu (Part 1: 4.2-3, 113.42, and Part 2: 211.69)

- The feet of Vishnu should be adored as Kurma, and 'on Dvadasi lord Kurma-Narayana should be propitiated by giving gifts to Brahmins with daksina' (Part 1: 40.8)

Vayu Purana

| Vayu | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| N/A | The churning is mentioned in the context of why Shiva has a blue throat due to swallowing poison, albeit without mention of Kurma. There are no notable mentions in either parts.[195][196] |

In the Vayu Purana, the legend of Samudra manthan is only briefly mentioned. Kurma is not mentioned in this account or seemingly at all in this Purana. Otherwise, the allegory of the tortoise drawing in its limbs is made at least twice in regards to withdrawing passions and desires (Part 1: 11.19-22 and Part 2: 31.93).

Vishnu Purana

| VIshnu | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Volume 6 (Book 1): IV (pp. 58), IX (pp, 135-151);[20] Volume 7 (Book 2): II (pp. 125)[197] | The Vishnu Purana is in six books, here cited as part of the works of H.H. Wilson. Kurma is not mentioned in books 3, 4, 5, or 6.[198][199][200] |

In the midst of the milky sea, Hari himself, in the form of a tortoise, served as a pivot for the mountain, as it was whirled around. The holder of the mace and discus [Vishnu] was present, in other forms, amongst the gods and demons, and assisted to drag the monarch of the serpent race [Vasuki, used as a rope].

— Works by the late Horace Hayman Wilson (Volume 6), Vishnu Purana (Book I), Chapter IX (9), pp. 143

In the Vishnu Purana, the churning of the ocean of Milk takes place after the sage Durvasas - stated by Wilson to be 'an incarnation of a portion of Siva' (footnote 1, pp. 135) - curses Indra, resulting in the ruin of the Devas, the Earth, and the general population, as 'all beings became devoid of steadiness' and morality. On the northern shore of the Ocean of Milk, Hari is sought for refuge, and enjoins the Devas to churn the Ocean for Ambrosia with the Asuras, using the Mandara Mountain as a churning rod and Vasuki as the rope.

During the churning, Vishnu 'in the form of a tortoise [Kurma], served as a pivot for the mountain... [and] in other forms, amongst the gods and demons, [to] drag the monarch of the serpent race [to help churn the Ocean]'. Auspicious items and beings (e.g. Varuni) are first generated, before poison emerges 'of which the snake-gods (Nagas) took possession' (i.e. not Shiva), followed by Dhanvantari with the Amrita, and Laksmi. The 'indignant Daityas' seize the Amrita before Vishnu incarnates as Mohini to deceive them and give the Amrita to the Devas. A battle ensues, but the Asuras and defeated and flee to Patala (Book 1: IX). Other details include:

Upa-Puranas

Kalki Purana

During the Great Churning, when the gods and the demons failed to find a solid support to base their churner at, you assumed the form of the Koorma (Tortoise) to solve their problem and had the ocean properly churned.

— Kalki Purana (translated by B.K. Chaturvedi, 2004), Chapter 10, Verse 23[201]

The Kalki Purana is a prophetic minor work set at the end of Kali Yuga.

Vedantas

Laghu Yoga Vasishtha

In five creations has the earth disappeared and been got back by Vishnu in his Kurma (tortoise) Avatar. Twelve times has the Ocean of Milk been churned. All these I was a direct witness of. Thrice has Hiranyaksha taken away the earth to Patala. Six times has Vishnu incarnated as Parasurama... Buddha has incarnated again and again in 100 Kali Yugas.

— Laghu Yoga Vasishtha (translated by K. Narayanaswami Aiyer, 1896), Nirvana Prakarana, Chapter 1 ('The story of Bhusunda')[202]