Bob Clampett

Robert Emerson Clampett Sr. (May 8, 1913 – May 2, 1984) was an American animator, producer, director, and puppeteer best known for his work on the Looney Tunes animated series from Warner Bros. as well as the television shows Time for Beany and Beany and Cecil. Clampett was born and raised not far from Hollywood and, early in his life, expressed an interest in animation and puppetry. After leaving high school a few months shy of graduating in 1931, Clampett joined the team at Harman-Ising Productions and began working on the studio's newest short subjects, titled Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies.

Bob Clampett | |

|---|---|

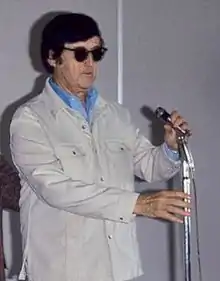

Clampett speaking at the 1976 San Diego Comic Convention | |

| Born | Robert Emerson Clampett May 8, 1913 San Diego, California, U.S. |

| Died | May 2, 1984 (aged 70) |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn – Hollywood Hills Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Otis College of Art and Design |

| Occupation | Animator, director, producer, puppeteer |

| Years active | 1931–1984 |

| Employer |

|

| Spouse(s) | Sody Clampett (m. 1955–1984) |

| Children | 3 |

Clampett was promoted to a directorial position in 1937 and during his fifteen years at the studio, directed 84 cartoons later deemed classic and designed some of the studio's most famous characters, including Porky Pig, Daffy Duck, and Tweety. Among Clampett's most acclaimed films are Porky in Wackyland (1938) and The Great Piggy Bank Robbery (1946). Clampett left Warner Bros. Cartoons in 1945 and turned his attention to television, creating the puppet show Time for Beany in 1949. A later animated version of the series, titled Beany and Cecil, was initially broadcast on ABC in 1962 and was rerun until 1967. The series is considered the first fully creator-driven television series and carried the byline "a Bob Clampett Cartoon".

In his later years, Clampett toured college campuses and animation festivals as a lecturer on the history of animation. His Warner cartoons have seen renewed praise in decades since for their surrealistic qualities, energetic and outrageous animation, and irreverent humor. Animation historian Jerry Beck lauded Clampett for "putting the word 'looney' in Looney Tunes."

Early life

Robert Emerson Clampett was born in San Diego, California on May 8, 1913, to Robert Caleb Clampett and Mildred Joan Merrifield. The elder Clampett was born in Nenagh, County Tipperary, Ireland in 1882, and he immigrated to the United States with his parents at age two in 1884.[1] Clampett was displaying extraordinary art skills by the age of five.[2] From the beginning, Clampett was intrigued with and influenced by Douglas Fairbanks, Lon Chaney, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, and he began making film short-subjects in his garage beginning when he was twelve.[3] While living in Hollywood as a young boy, Clampett and his mother Joan lived next door to Charlie Chaplin and his brother Sydney Chaplin. Clampett also recalled watching his father play handball at the Los Angeles Athletic Club with another of the great silent comedians, Harold Lloyd. From his early teens Clampett showed an interest in animation and puppetry. Clampett made hand puppets as a child and, before adolescence, had completed what animation historian Milt Gray describes as "a sort of prototype, a kind of nondescript dinosaur sock puppet that later evolved into Cecil." In high school, Clampett drew a full-page comic about the nocturnal adventures of a pussycat, later published in color in a Sunday edition of the Los Angeles Times. King Features took note and offered Clampett a "cartoonist's contract" to begin a seventy-five dollars a week after high school. King Features allowed Clampett to work in their Los Angeles art department on Saturdays and vacations during high school. On occasion, King Features would print one of Clampett's cartoons for encouragement. In addition, they paid his way through Otis Art Institute, where Clampett learned to paint with oils and to sculpt.[4]

Clampett attended both Glendale High School and Hoover High School in Glendale, California but left Hoover a few months short of graduating in 1931. Afterwards, Clampett found a job working at a doll factory owned by his aunt, Charlotte Clark. Clark was looking for an appealing item to sell and Clampett suggested Mickey Mouse due to growing popularity. Unable to find a drawing of the character anywhere, Clampett took his sketchpad to the movie theater and came out with several sketches. Clark was concerned with the copyright, so the two drove to the Disney studio. Walt and Roy Disney were delighted and they set up a business not far from the Disney studio. Clampett recalled his short time working for Disney: "Walt Disney himself sometimes came over in an old car to pick up the dolls; he would give them out to visitors to the studio and at sales meetings. I helped him load the dolls in the car. One time his car, loaded with Mickeys, wouldn't start, and I pushed while Walt steered, until it caught, and he took off."[4]

Career

Looney Tunes

Clampett was, in his words, so "enchanted" by the new medium of sound cartoons that he instead joined Harman-Ising Studios in 1931 for ten dollars a week. Leon Schlesinger viewed one of Clampett's 16mm films and was impressed, offering him an assistant position at the studio.[3] His first job was animating secondary characters in the first Merrie Melodie, Lady, Play Your Mandolin! (1931). The same year, Clampett began attending story meetings after submitting an idea eventually used for Smile, Darn Ya, Smile!. The two series were produced at Harman-Ising until mid-1933 when they split into Leon Schlesinger Productions. In his first years at the studio, Clampett mostly worked for Friz Freleng, under whose guidance Clampett grew into an able animator.[4] When he joined Harman-Ising, Bob Clampett was only 17 years old.[2]

By 1934, Schlesinger was in a bit of a crisis trying to find a well-known cartoon character. He noted that the Our Gang series consisted of nothing but "little kids doing things together," and a studio-wide drive to get ideas for an animal version of Our Gang commenced. Clampett submitted a drawing of a pig (Porky) and a black cat (Beans), and, in an imitation of the lettering on a can of Campbell's Pork and Beans, wrote "Clampett's Porky and Beans." Porky debuted in the Friz Freleng-directed I Haven't Got a Hat in 1935. Around the same time, Schlesinger announced a studio-wide contest, with a money prize to whichever member of the staff turned in the best original story. Clampett's story won first prize and was made into My Green Fedora, also directed by Freleng.[4]

Clampett felt encouraged after these successes and began writing more story contributions. After Schlesinger realized he needed another unit, he made a deal with Tex Avery, naming Clampett his collaborator. They were moved to a ramshackle building used by gardeners and WB custodial staff for storage of cleaning supplies, solvents, brooms, lawnmowers and other implements.[3] Working apart from the other animators in the small, dilapidated wooden building in the middle of the Vitaphone lot, Avery and Clampett soon discovered they were not the only inhabitants - they shared the building with thousands of tiny termites. They christened the building "Termite Terrace", a name eventually used by historians to describe the entire studio. The two soon developed an irreverent style of animation that would set Warner Bros. apart from its competitors.[2] They were soon joined by animators Chuck Jones, Virgil Ross, and Sid Sutherland, and worked virtually without interference on their new, groundbreaking style of humor for the next year. It was a wild place with an almost college fraternity-like atmosphere. Animators would frequently pull pranks such as gluing paper streamers to the wings of flies. Leon Schlesinger, who rarely ventured there, was reputed on one visit to have remarked in his lisping voice, "Pew, let me out of here! The only thing missing is the sound of a flushing toilet!!"

On the side, Clampett directed a sales film, co-animated by Chuck Jones and in-betweened by Robert Cannon. Clampett filmed Cannon in live action as the hero and rotoscoped it into the film. Clampett planned to leave Leon Schlesinger Productions, but Schlesinger offered him a promotion to director and more money if he would stay. Clampett was promoted to director in late 1936, directing a color sequence in the feature When's Your Birthday? (1937). This led to what was essentially a co-directing stint with fellow animator Chuck Jones for the financially ailing Ub Iwerks, whom Schlesinger subcontracted to produce several Porky Pig shorts. These shorts featured the short-lived and generally unpopular Gabby Goat as Porky's sidekick. Despite Clampett and Jones' contributions, however, Iwerks was the only credited director. Clampett's first cartoon with a directorial credit was Porky's Badtime Story. Under the Warner system, Clampett had complete creative control over his own films, within severe money and time limitations (he was only given $3,000 and four weeks to complete each short).[4] During production of Porky's Duck Hunt in 1937, Avery created a character that would become Daffy Duck and Clampett animated the character for the first time.[4]

Clampett was so popular in theaters that Schlesinger told the other directors to imitate him, emphasizing gags and action.[2] When Tex Avery departed in 1941, Avery's unit was taken over by Clampett, while Norman McCabe took over Clampett's old unit. Clampett finished Avery's remaining unfinished cartoons. When McCabe joined the armed forces, Frank Tashlin rejoined Schlesinger as director, and that unit was eventually turned over to Robert McKimson. Milton Gray notes that from The Hep Cat (1942) on, the cartoons become even more wild as Clampett's experimentation reached a peak.[2] Clampett later created the character of Tweety, introduced in A Tale of Two Kitties in 1942. His cartoons grew increasingly violent, irreverent, and surreal, not beholden to even the faintest hint of real-world physics, and his characters have been argued to be easily the most rubbery and wacky of all the Warner directors'. Clampett was heavily influenced by the Spanish surrealist artist Salvador Dalí, as is most visible in Porky in Wackyland (1938), wherein the entire short takes place within a Dalí-esque landscape complete with melting objects and abstracted forms. Clampett and his work can even be considered part of the surreal movement, as it incorporated film as well as static media.[2] It was largely Clampett's influence that would impel the Warners directors to shed the final vestiges of all Disney influence. Clampett was also known for creating some brief voices or sound effects in some of the cartoons, for some of these he impersonated the Warner Bros. zooming in shield sound effect (otherwise known as "Bay-woop!").[4] Clampett liked to bring contemporary cultural movements into his cartoons, especially jazz; film, magazines, comics, novels, and popular music are referenced in Clampett shorts, most visible in Book Revue (1946), where performers are drawn onto various celebrated books.[2]

Clampett was a good source for censorship stories, though the accuracy of his recollections has been disputed. According to an interview published in Funnyworld #12 (1971), Clampett had a method for ensuring that certain elements of his films would escape the censors' cut. It consisted of adding material aimed just at the censors; they would focus on cutting those and thus leave in the ones he actually wanted.[5]

Clampett was fired from the studio in May 1945, although short films directed by him would continue to be released until late 1946. The Big Snooze was his final cartoon with the studio and was one for which he did not get screen credit (only one of three he directed pitting Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd). While the generally accepted story was that Clampett left over matters of artistic freedom, Arthur Davis (an animator who took over Clampett’s unit the same year, and finished The Big Snooze) remembered that Clampett was fired by then-cartoon studio executive Eddie Selzer, who was far less tolerant of him than Leon Schlesinger, despite that some people claimed that he left the studio on his own. Clampett's style was becoming increasingly divergent from those of Freleng and Jones, the other unit directors, and this is thought by some to be the primary reason for his departure. The Warners style that he was so instrumental in developing was leaving him behind. Warner Bros. had recently bought the rights to the entire Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies studio from Schlesinger and, while his cartoons of 1946 are today considered on the cutting edge of the art for that period, at the time, Clampett was ready to seek new challenges.[4] Clampett left at what some considered the peak of his creativity and against everyone's advice.[3]

Later career and Beany and Cecil

In 1946 after Warner Bros. bought out Leon Schlesinger, his key executives Henry Binder and Ray Katz went to Screen Gems and took Clampett with them.[6] Clampett worked for a time at Screen Gems, then the cartoon division of Columbia Pictures, as a screenwriter and gag writer. In 1947 Republic Pictures incorporated animation (by Walter Lantz) into its Gene Autry feature film Sioux City Sue. It turned out well enough for Republic to dabble in animated cartoons; Bob Clampett directed a single cartoon, It's a Grand Old Nag, featuring the equine character Charlie Horse. Republic management, however, had second thoughts due to dwindling profits, and they discontinued the series.[7] Clampett took his direction credit under the name "Kilroy".

In 1949, Clampett turned his attention to television, where he created the famous puppet show Time for Beany. The show, featuring the talents of voice artists Stan Freberg and Daws Butler, would earn Clampett three Emmys. Groucho Marx and Albert Einstein were both fans of the series. [8] In 1952, he created the Thunderbolt the Wondercolt television series and the 3D prologue to Bwana Devil featuring Beany and Cecil. In 1954, he directed Willy the Wolf (the first puppet variety show on television), as well as creating and voicing the lead in the Buffalo Billy television show. In the late 1950s, Clampett was hired by Associated Artists Productions to catalog the pre-August 1948[9] Warner cartoons it had just acquired. He also created an animated version of the puppet show called Beany and Cecil, whose 26 half-hour episodes were first broadcast on ABC in 1959 and were rerun on the network for five years.[10]

In his later years, Bob Clampett toured college campuses and animation festivals as a lecturer on the history of animation. In 1974 he was award an Inkpot Award.[11] In 1975 he was the focus of a documentary entitled Bugs Bunny: Superstar, the first documentary to examine the history of the Warner Bros. cartoons. Clampett, whose collection of drawings, films, and memorabilia from the golden days of Termite Terrace was legendary, provided nearly all of the behind-the-scenes drawings and home-movie footage for the film; furthermore, his wife, Sody Clampett, is credited as the film's production co-ordinator. In an audio commentary recorded for Bugs Bunny: Superstar, director Larry Jackson claimed that in order to secure Clampett's participation, and access to Clampett's collection of Warners history, he had to sign a contract that stipulated Clampett would host the documentary and also have approval over the final cut. Jackson also claimed that Clampett was very reluctant speaking about the other directors and their contributions.[12]

Clampett died of a heart attack on May 2, 1984 in Detroit, Michigan, six days before his 71st birthday,[13] while touring the country to promote the home video release of Beany & Cecil cartoons. He is buried in Forest Lawn Hollywood Hills.[14][15]

Controversy

Though Clampett's contribution to the Warner Brothers animation legacy was considerable and inarguable, he has been criticized by his peers as "a shameless self-promoter who provoked the wrath of his former Warner's colleagues in later years for allegedly claiming credit for ideas that were not his."[16] Chuck Jones particularly disliked Clampett and intentionally avoided making any mention of his association with him in his 1979 compilation film The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie (in which Jones lists himself and other Warners directors), although he did briefly mention working with Clampett in his 1989 autobiography "Chuck Amuck: The Life and Times of An Animated Cartoonist" and his 1998 interview for the American Television Archive.[17] Some of this animosity appears to have come from Clampett's perceived "golden boy" status at the studio (Clampett's mother was said to be a close friend of cartoon producer Leon Schlesinger), which allowed him to ignore studio rules that everyone else was expected to follow. In addition, Mel Blanc (the voice actor who had worked with Clampett at the same studio for ten years) also accused Clampett of being an "egotist who took credit for everything."[18]

Martha Sigall, on the other hand, recalled Clampett as "an enthusiastic and fun type of guy". She describes him as consistently nice to her and very generous when it came to gifts or donations to a cause.[19] She had left the Termite Terrace in 1943 and did not meet Clampett again until 1960. She did, however, hear from people whom Clampett helped break into the animation business and/or mentored.[20]

Beginning with a magazine article in 1946, shortly after he left the studio, Clampett repeatedly referred to himself as "the creator" of Bugs Bunny, often adding the side-note that he used Clark Gable's carrot-eating scene in It Happened One Night as inspiration for his "creation." (Clampett can be observed making this claim in Bugs Bunny: Superstar.) A viewing of the early Bugs cartoons of the late 1930s and early 1940s, however, clearly demonstrates that the character was not "created" as a whole at one time, but rather evolved in personality, voice, and design over several years through the efforts of Tex Avery, Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng, Cal Dalton, Ben Hardaway, Robert McKimson, Bob Givens and Mel Blanc, in addition to Clampett's contributions.

As the aforementioned Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie was compiled by Jones (along with Friz Freleng) the omission of Clampett is not surprising. (The other two directorial fathers Bugs claims to have had are Avery, who directed A Wild Hare, his first official short, and McKimson, who is the least known of the three best-known Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies directors, but drew the definitive Bugs Bunny model sheet. Depending on the source, number one could be either Jones or Freleng.) Furthermore, in Bugs Bunny: Superstar, Clampett takes credit for drawing the model sheet for the first Porky Pig cartoon, I Haven't Got a Hat (1935), even though it was actually drawn by Friz Freleng.[21][22]

Animation historian Milton Gray details the long and bitter rivalry between Clampett and Jones in an essay titled "Bob Clampett Remembered." Gray, a personal friend of Clampett, calls the controversy "a deliberate and vicious smear campaign by one of Bob's rivals in the cartoon business." He reveals that Jones was angry at Clampett for making some generalizations in his 1970 interview with Funnyworld that gave Clampett too much credit, including taking sole credit for not only Bugs and Daffy but also Jones's Sniffles character and Freleng's Yosemite Sam. He writes that Jones began making additional accusations against Clampett, such as that Clampett would "go around the studio at night, looking at other directors' storyboards for ideas he could steal for his own cartoons." Jones wrote a letter of accusations in 1975 and, according to Gray, distributed copies to every fan he met: seemingly the genesis of the growing controversy. Gray asserts that Clampett was a "kind, generous man [who was] deeply hurt and saddened by Jones's accusations. […] I feel that Bob Clampett deserves tremendous respect and gratitude for the wonderful work that he left us."[23] Other Warner Bros. peers such as musical coordinator Carl Stalling and animator Tex Avery stood by Clampett during his talks on the cartoon industry in the 1960s and 1970s.

Legacy

Since 1984, The Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award is given each year at the Eisner Awards. Recipients of the award include June Foray, Jack Kirby, Sergio Aragonés, Patrick McDonnell, Maggie Thompson, Ray Bradbury and Mark Evanier.[24]

Clampett's Tin Pan Alley Cats (1943) was chosen by the Library of Congress as a "prime example of the music and mores of our times" and a print was buried in a time capsule in Washington, D.C. so future generations might see it.[4] Porky in Wackyland (1938) was inducted into the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 2000, deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[25]

John Kricfalusi, best known as the creator of The Ren & Stimpy Show, got to know Clampett in his later years and has reflected on those times as inspirational. Kricfalusi calls Clampett his favorite cartoon director and calls The Great Piggy Bank Robbery (1946) his favorite cartoon: "I saw this thing and it completely changed my life, I thought it was the greatest thing I'd ever seen, and I still think it is."[26]

Animation historian Leonard Maltin has called Clampett's cartoons "unmistakable." Milton Gray believes that Schlesinger put Clampett in charge of the black and white cartoon division in order to save it, and many historians have singled out a scene in Porky's Duck Hunt, in which Daffy exits, as a defining Clampett moment. Maltin called it "a level of wackiness few moviegoers had ever seen."[27]

Historian Charles Solomon noted a rubbery, flexible animation quality visible in all Clampett's shorts, and Maltin noted an "energetic, comic anarchy." While Clampett's cartoons were not as well known in the latter half of the 20th century because television syndicators only had the rights to the post-1948 Warner cartoons, his creations have increased in notoriety and acclaim in recent decades.[2]

Clampett is survived by his three children who currently preserve his work and their names are Robert Clampett Jr., who worked for his father as a puppeteer at Bob Clampett Productions, Ruth Clampett, who is an author for several books including a book about a animated couple; she also founded Clampett Studio collections after her fathers death, and Cheri Clampett, a therapeutic yoga specialist.[15] [28][29]

Films with Bob Clampett's involvement

Warner Bros.

|

|

|

Shorts that didn't enter production

Republic Pictures

- It's a Grand Old Nag (1947) (credited as Kilroy)

Sources

- Cohen, Karl F. (2004), "Censorship of Theatrical Animation", Forbidden Animation: Censored Cartoons and Blacklisted Animators in America, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0786420322

- Sigall, Martha (2005). "The Boys of Termite Terrace". Living Life Inside the Lines: Tales from the Golden Age of Animation. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781578067497.

References

- https://www.nenaghguardian.ie/news/roundup/articles/2017/10/04/4146698-nenagh-connection-with-warner-brothers-cartoon-creator/

- Jerry Beck, John Kricfalusi, Ruth Clampett, Milton Gray, Leonard Maltin et al. (2004). Looney Tunes Golden Collection Volume 2. Special Features: Man from Wackyland: The Art of Bob Clampett (DVD). Warner Home Video.

- Story, Robert (September 1999). "Bob Clampett, Boy Wonder Of Stage C". Animation World Magazine. 4 (6). Archived from the original on 2011-12-22. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- Barrier, Michael; Milt Gray (1970). "An Interview with Bob Clampett". Funnyworld. 12. Archived from the original on 2010-09-23.

- Cohen (2004), p. 36-37

- Leonard., Maltin (1980). Of mice and magic : a history of American animated film. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070398356. OCLC 702546548.

- Beck, Jerry; Amidi, Amid. "It's a Grand Old Nag". Cartoon Brew. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2009.

- https://www.lambiek.net/artists/c/clampett_bob.htm

- The latest released WB cartoon sold to a.a.p. was Haredevil Hare, released on July 24, 1948.

- "Matty's Funday Funnies". Toon Tracker. Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2012 – via Wayback Machine.

- Inkpot Award

- "Bob Clampett Superstar". What About Thad?. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- "Bob Clampett's Beany and Cecil". Toon Tracker. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved October 30, 2009.

- "Find a Service, Grave or Obituary". sgo.forestlawn.com. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Cartoonist Bob Clampett, who developed the Beany and Cecil...

- https://www.lambiek.net/artists/c/clampett_bob.htm

- http://www.emmytvlegends.org/interviews/people/chuck-jones# Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine Chuck Jones' interview for the Archive of American Television - 22.25

- Blanc, Mel. (1988). That's Not All, Folks!. Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-51244-3

- Sigall (2005), p. 50

- Sigall (2005), p. 54

- Barrier (1999); pg 365

- Barrier (1999); pg 329

- Gray, Milton. "Bob Clampett Remembered". Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2011.

- "Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award". Retrieved 2020-09-15.

- "Librarian of Congress Names 25 More Films to National Film Registry". loc.gov. Archived from the original on 6 September 2009. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Kricfalusi, John (2004). Looney Tunes Golden Collection Volume 2 DVD commentary for the short The Great Piggy Bank Robbery (DVD). Warner Home Video.

- "Search | Britannica.com". Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- Rob Clampett

- Ruth Clampett

- https://vignette.wikia.nocookie.net/looneytunes/images/a/a3/Screen_Shot_2020-05-08_at_1.10.06_PM.png/revision/latest?cb=20200912003534

- https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/animation-anecdotes-136/

- https://profilesinhistory.com/flipbooks/A116Animation/files/basic-html/page12.html

Further reading

External links

- Lambiek Comiclopedia article.

- In His Own Words: Bob Clampett on "Time for Beany"

- Robert Clampett at IMDb

- Senses of Cinema: Great Directors Critical Database

- Clampett Studio Collections

- On a Desert Island with....Bob Clampett

- Michael Barrier's interview with Bob Clampett

- Correspondence between Tex Avery and Chuck Jones concerning Michael Barrier's interview with Bob Clampett

- Milt Gray's essay on Bob Clampett

- Toon Tracker Beany and Cecil page

- Toon Tracker Matty's Funday Funnies page

- Bob Clampett at Find a Grave