Bobby Charlton

Sir Robert Charlton CBE (born 11 October 1937) is an English former footballer who played as a midfielder. He is regarded as one of the greatest players of all time,[2] and was a member of the England team that won the 1966 FIFA World Cup, the year he also won the Ballon d'Or. He played almost all of his club football at Manchester United, where he became renowned for his attacking instincts, his passing abilities from midfield and his ferocious long-range shot, as well as his fitness and stamina. He was cautioned only twice in his career; once against Argentina in the 1966 World Cup, and once in a league match against Chelsea. His elder brother Jack, who was also in the World Cup-winning team, was a former defender for Leeds United and international manager.

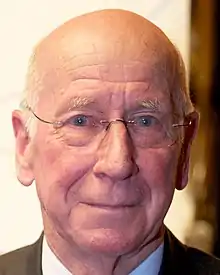

Charlton at Manchester Town Hall in November 2010 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Robert Charlton[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Date of birth | 11 October 1937 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Place of birth | Ashington, Northumberland, England | ||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Position(s) |

Attacking midfielder Forward | ||||||||||||||||||

| Youth career | |||||||||||||||||||

| East Northumberland Schools | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1953–1956 | Manchester United | ||||||||||||||||||

| Senior career* | |||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | Apps | (Gls) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1956–1973 | Manchester United | 606 | (199) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1974–1975 | Preston North End | 38 | (8) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1976 | Waterford | 3 | (1) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1978 | Newcastle KB United | 1 | (0) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1980 | Perth Azzurri | 3 | (2) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1980 | Blacktown City | 1 | (1) | ||||||||||||||||

| Total | 652 | (211) | |||||||||||||||||

| National team | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1953 | England Schoolboys | 4 | (5) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1954 | England Youth | 1 | (1) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1958–1960 | England U23 | 6 | (5) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1958–1970 | England | 106 | (49) | ||||||||||||||||

| Teams managed | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1973–1975 | Preston North End | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1983 | Wigan Athletic (caretaker manager) | ||||||||||||||||||

Honours

| |||||||||||||||||||

| * Senior club appearances and goals counted for the domestic league only | |||||||||||||||||||

Born in Ashington, Northumberland, Charlton made his debut for the Manchester United first-team in 1956, and over the next two seasons gained a regular place in the team, during which time he survived the Munich air disaster of 1958 after being rescued by Harry Gregg. Charlton is the ony surviving person of the crash. After helping United to win the Football League First Division in 1965, he won another First Division title with United in 1967. In 1968, he captained the Manchester United team that won the European Cup, scoring two goals in the final to help them become the first English club to win the competition. He was named in the England squad for four World Cups (1958, 1962, 1966 and 1970), though did not play in the first. At the time of his retirement from the England team in 1970, he was the nation's most capped player, having turned out 106 times at the highest level. (As of November 2019, this record had been surpassed by six players.)

Charlton was both Manchester United's and England's long-time record goalscorer, and United's long-time record appearance maker, as well as briefly England's, until Bobby Moore overtook his 106 caps in 1973. His appearance record of 758 for United took until 2008 to be beaten, when Ryan Giggs did so in that year's Champions League final.[3] With 249 goals, he is currently United's second-highest all-time goalscorer, after his record was surpassed by Wayne Rooney in 2017. He is also the second-highest goalscorer for England, after his record of 49 goals which was held until 2015 was again surpassed by Rooney.

He left Manchester United to become manager of Preston North End for the 1973–74 season.[4] He changed to player-manager the following season. He next accepted a post as a director with Wigan Athletic, then became a member of Manchester United's board of directors in 1984[5] and remains one as of the 2020–21 season.[6]

Early life

Charlton was born in Ashington, Northumberland, England on 11 October 1937 to coal miner Robert "Bob" Charlton (24 May 1909-April 1982)[7][8] and Elizabeth Ellen "Cissie" Charlton (née Milburn) (11 November 1912 – 25 March 1996). He is related to several professional footballers on his mother's side of the family: his uncles were Jack Milburn (Leeds United and Bradford City), George Milburn (Leeds United and Chesterfield), Jim Milburn (Leeds United and Bradford Park Avenue) and Stan Milburn (Chesterfield, Leicester City and Rochdale), and legendary Newcastle United and England footballer Jackie Milburn, was his mother's cousin. However, Charlton credits much of the early development of his career to his grandfather Tanner and his mother Cissie.[9] His elder brother, Jack, initially worked as a miner before applying to the police, only to also become a professional footballer with Leeds United.

Club career

On 9 February 1953, then a Bedlington Grammar School pupil, Charlton was spotted playing for East Northumberland schools by Manchester United chief scout Joe Armstrong.[10] Charlton went on to play for England Schoolboys and the 15-year-old signed with United on 1 January 1953, along with Wilf McGuinness, also aged 15.[11] Initially his mother was reluctant to let him commit to an insecure football career, so he began an apprenticeship as an electrical engineer; however, he went on to turn professional in October 1954.[12]

Charlton became one of the famed Busby Babes, the collection of talented footballers who emerged through the system at Old Trafford in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s as Matt Busby set about a long-term plan of rebuilding the club after the Second World War. He worked his way through the pecking order of teams, scoring regularly for the youth and reserve sides before he was handed his first team debut against Charlton Athletic in October 1956. At the same time, he was doing his National service with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps in Shrewsbury, where Busby had advised him to apply as it meant he could still play for Manchester United at the weekend. Also doing his army service in Shrewsbury at the same time was his United teammate Duncan Edwards.[13]

Charlton played 14 times for United in that first season, scoring twice on his debut and managing a total of 12 goals in all competitions, and including a hat-trick in a 5–1 away win over Charlton Athletic in February. United won the league championship but were denied the 20th century's first "double" when they controversially lost the 1957 FA Cup Final to Aston Villa. Charlton, still only 19, was selected for the game, which saw United goalkeeper Ray Wood carried off with a broken cheekbone after a clash with Villa centre forward Peter McParland. Though Charlton was a candidate to go in goal to replace Wood (in the days before substitutes, and certainly before goalkeeping substitutes), it was teammate Jackie Blanchflower who ended up between the posts.

Charlton was an established player by the time the next season was fully underway, which saw United, as current League champions, become the first English team to compete in the European Cup. Previously, the Football Association had scorned the competition, but United made progress, reaching the semi-finals where they lost to holders Real Madrid. Their reputation was further enhanced the next season as they reached the quarter-finals to play Red Star Belgrade. In the first leg at home, United won 2–1. The return in Yugoslavia saw Charlton score twice as United stormed 3–0 ahead, although the hosts came back to earn a 3–3 draw. However, United maintained their aggregate lead to reach the last four and were in jubilant mood as they left to catch their flight home, thinking of an important League game against Wolves at the weekend.

Munich air disaster

The aeroplane which took the United players and staff home from Zemun Airport needed to stop in Munich to refuel. This was carried out in worsening weather, and by the time the refuelling was complete and the call was made for the passengers to re-board the aircraft, the wintry showers had taken hold and snow had settled heavily on the runway and around the airport. There were two aborted take-offs which led to concern on board, and the passengers were advised by a stewardess to disembark again while a minor technical error was fixed.

The team were back in the airport terminal for barely ten minutes when the call came to reconvene on the plane, and a number of passengers began to feel nervous. Charlton and teammate Dennis Viollet swapped places with Tommy Taylor and David Pegg, who had decided they would be safer at the back of the plane.

The plane clipped the fence at the end of the runway on its next take-off attempt and a wing tore through a nearby house, setting it alight. The wing and part of the tail came off and hit a tree and a wooden hut, the plane spinning along the snow until coming to a halt. It had been cut in half.

Charlton, strapped into his seat, had fallen out of the cabin; when United goalkeeper Harry Gregg (who had somehow got through a hole in the plane unscathed and begun a one-man rescue mission) found him, he thought he was dead. Nevertheless, he grabbed both Charlton and Viollet by their trouser waistbands and dragged them away from the plane, in constant fear that it would explode. Gregg returned to the plane to try to help the appallingly injured Busby and Blanchflower, and when he turned around again, he was relieved to see that Charlton and Viollet, both of whom he had presumed to be dead, had got out of their detached seats and were looking into the wreckage.

Charlton suffered cuts to his head and severe shock, and was in hospital for a week. Seven of his teammates had perished at the scene, including Taylor and Pegg, with whom he and Viollet had swapped seats prior to the fatal take-off attempt. Club captain Roger Byrne was also killed, along with Mark Jones, Billy Whelan, Eddie Colman and Geoff Bent. Duncan Edwards died a fortnight later from the injuries he had sustained. In total, the crash claimed 23 lives. Initially, ice on the wings was blamed, but a later inquiry declared that slush on the runway had made a safe take-off almost impossible.

Of the 44 passengers and crew (including the 17-strong Manchester United squad), 23 people (eight of them Manchester United players) died as a result of their injuries in the crash. Charlton survived with minor injuries. Of the eight other players who survived, two of them were injured so badly that they never played again.

Charlton was the first injured survivor to leave hospital. Harry Gregg and Bill Foulkes were not hospitalised, for they escaped uninjured. He arrived back in England on 14 February 1958, eight days after the crash. As he convalesced with family in Ashington, he spent some time kicking a ball around with local youths, and a famous photograph of him was taken. He was still only 20 years old, yet now there was an expectation that he would help with the rebuilding of the club as Busby's aides tried to piece together what remained of the season.

Resuming his career

Charlton returned to playing in an FA Cup tie against West Bromwich Albion on 1 March; the game was a draw and United won the replay 1–0. Not unexpectedly, United went out of the European Cup to A.C. Milan in the semi-finals to a 5–2 aggregate defeat and fell behind in the League. Yet somehow they reached their second consecutive FA Cup final, and the big day at Wembley coincided with Busby's return to work. However, his words could not inspire a side which was playing on a nation's goodwill and sentiment, and Nat Lofthouse scored twice to give Bolton Wanderers a 2–0 win.

Further success with Manchester United came at last when they beat Leicester City 3–1 in the FA Cup final of 1963, with Charlton finally earning a winners' medal in his third final. Busby's post-Munich rebuilding programme continued to progress with two League championships within three seasons, with United taking the title in 1965 and 1967. A successful (though trophyless) season with Manchester United had seen him take the honours of Football Writers' Association Footballer of the Year and European Footballer of the Year into the competition.

Manchester United reached the 1968 European Cup Final, ten seasons after Munich. Even though other clubs had taken part in the competition in the intervening decade, the team which got to this final was still the first English side to do so. On a highly emotional night at Wembley, Charlton scored twice in a 4–1 win after extra time against Benfica and, as United captain, lifted the trophy.

During the early 1970s Manchester United were no longer competing among the top teams in England, and at several stages were battling against relegation. At times, Charlton was not on speaking terms with United's other superstars George Best and Denis Law, and Best refused to play in Charlton's testimonial match against Celtic, saying that "to do so would be hypocritical".[14] Charlton left Manchester United at the end of the 1972–73 season, having scored 249 goals and set a club record of 758 appearances, a record which Ryan Giggs broke in the 2008 UEFA Champions League Final.

His last game for Manchester United was against Chelsea at Stamford Bridge on 28 April 1973, and before the game the BBC cameras for Match of the Day captured the Chelsea chairman handing him a commemorative cigarette case. Chelsea won the match 1–0.[15] Coincidentally, this day also marked his brother Jackie's last appearance as well (for Leeds). Charlton's final goal for the club came a month earlier, on 31 March, in a 2–0 win at Southampton, also in the First Division.[16]

He was the subject of This Is Your Life in 1969 when he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews at The Sportsman's Club in central London.

International career

Charlton's emergence as the country's leading young football talent was completed when he was called up to join the England squad for a British Home Championship game against Scotland at Hampden Park on 19 April 1958, just over two months after he had survived the Munich air disaster.

Charlton was handed his debut as England romped home 4–0, with the new player gaining even more admirers after scoring a magnificent thumping volley dispatched with authority after a cross by the left winger Tom Finney. He scored both goals in his second game as England beat Portugal 2–1 in a friendly at Wembley; and overcame obvious nerves on a return to Belgrade to play his third match against Yugoslavia. England lost that game 5–0 and Charlton played poorly.

1958 World Cup

Charlton was selected for the squad which competed at the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, but he did not play.[17]

In 1959 he scored a hat-trick as England demolished the US 8–1; and his second England hat-trick came in 1961 in an 8–0 thrashing of Mexico. He also managed to score in every British Home Championship tournament he played in except 1963 in an association with the tournament that lasted from 1958 to 1970 and included 16 goals and 10 tournament victories (five shared).

1962 World Cup

He played in qualifiers for the 1962 World Cup in Chile against Luxembourg and Portugal and was named in the squad for the finals themselves. His goal in the 3–1 group win over Argentina was his 25th for England in just 38 appearances, and he was still only 24 years old; but his individual success could not be replicated by that of the team, which was eliminated in the quarter-final by Brazil, who went on to win the tournament.

By now, England were coached by Alf Ramsey who had managed to gain sole control of the recruitment and team selection procedure from the committee-based call-up system which had lasted up to the previous World Cup. Ramsey had already cleared out some of the older players who had been reliant on the loyalty of the committee for their continued selection. A hat-trick in the 8–1 rout of Switzerland in June 1963 took Charlton's England goal tally to 30, equalling the record jointly held by Tom Finney and Nat Lofthouse; Charlton's 31st goal against Wales in October the same year gave him the record alone.

Charlton's role was developing from traditional inside-forward to what today would be termed an attacking midfield player, with Ramsey planning to build the team for the 1966 World Cup around him. When England beat the USA 10–0 in a friendly on 27 May 1964, he scored one goal, his 33rd at senior level for England.[18]

His goals became a little less frequent, and indeed Jimmy Greaves, playing purely as a striker, overtook his England tally in October 1964. Nevertheless, Charlton was still scoring and creating freely, and as the tournament was about to start he was expected to become one of its stars and galvanise his established reputation as one of the world's best footballers.

1966 World Cup

England drew the opening game of the tournament 0–0 with Uruguay. Charlton scored the first goal in the 2–0 win over Mexico. This was followed by an identical scoreline against France, allowing England to qualify for the quarter-finals.

England defeated Argentina 1–0. The game was the only international match in which Charlton received a caution. They faced Portugal in the semi-finals. This turned out to be one of Charlton's most important games for England.

Charlton opened the scoring with a crisp side-footed finish after a run by Roger Hunt had forced the Portuguese goalkeeper out of his net; his second was a sweetly struck shot after a run and pull-back from Geoff Hurst. Charlton and Hunt were now England's joint-highest scorers in the tournament with three each, and a final against West Germany beckoned.

The final turned out to be one of Charlton's quieter days; he and a young Franz Beckenbauer effectively marked each other out of the game. England won 4–2 after extra time.

Euro 1968

Charlton's next England game was his 75th as England beat Northern Ireland; 2 caps later and he had become England's second most-capped player, behind the veteran Billy Wright, who was approaching his 100th appearance when Charlton was starting out and ended with 105 caps.

Weeks later he scored his 45th England goal in a friendly against Sweden, breaking the record of 44 set the previous year by Jimmy Greaves. He was then in the England team which made it to the semi-finals of the 1968 European Championships where they were knocked out by Yugoslavia in Florence. During the match Charlton struck a Yugoslav post. England defeated the Soviet Union 2–0 in the third place match.

In 1969, Charlton was appointed an OBE for services to football. More milestones followed as he won his 100th England cap on 21 April 1970 against Northern Ireland, and was made captain by Ramsey for the occasion. Inevitably, he scored. This was his 48th goal for his country – his 49th and final goal followed a month later in a 4–0 win over Colombia during a warm-up tour for the 1970 World Cup, designed to get the players adapted to altitude conditions. Charlton's inevitable selection by Ramsey for the tournament made him the first – and still, to date, only – England player to feature in four World Cup squads.

1970 World Cup

Shortly before the World Cup, Charlton was involved in the Bogotá Bracelet incident in which he and Bobby Moore were accused of stealing a bracelet from a jewellery store. Moore was later arrested and detained for four days before being granted a conditional release, while Charlton was not arrested.

England began the tournament with two victories in the group stages, plus a memorable defeat against Brazil. Charlton played in all three, though was substituted for Alan Ball in the final game of the group against Czechoslovakia. Ramsey, confident of victory and progress to the quarter-final, wanted Charlton to rest.

.jpg.webp)

England reached the last eight where they again faced West Germany. Charlton controlled the midfield and suppressed Franz Beckenbauer's runs from deep. England took a 2–0 lead in the 50th minute after goals from Alan Mullery and Martin Peters.[19] In the 69th minute, Beckenbauer pulled a goal back for the Germans and Ramsey soon replaced Charlton with Colin Bell, who further tested the German goalkeeper Sepp Maier and also provided a cross for Geoff Hurst, who missed a chance to score. West Germany, who had a habit of coming back from behind, eventually scored twice – a back header from Uwe Seeler made it 2–2. In extra-time, Geoff Hurst had a goal mysteriously ruled out[20] after which Gerd Müller's goal won the match 3–2. England were out and, after a record 106 caps and 49 goals, Charlton decided to end his international career at the age of 32. On the flight home from Mexico, he asked Ramsey not to consider him again. His brother Jack, two years his senior but 71 caps his junior, did likewise.

Charlton's caps record lasted until 1973 when Bobby Moore overtook him; he currently lies seventh in the all-time England appearances list behind Moore, Wayne Rooney, Ashley Cole, Steven Gerrard, David Beckham and Peter Shilton, whose own England career began in the first game after Charlton's had ended. Charlton's goalscoring record was surpassed by Wayne Rooney on 8 September 2015, when Rooney scored a penalty in a 2–0 win over Switzerland in a qualifying match for UEFA Euro 2016.[21]

Management career and directorships

Charlton became the manager of Preston North End in 1973, signing his former United and England teammate Nobby Stiles as player-coach. His first season ended in relegation, and although he began playing again, he left Preston early in the 1975–76 season after a disagreement with the board over the transfer of John Bird to Newcastle United.[22][23] He was appointed a CBE that year and began a casual association with BBC for punditry on matches, which continued for many years. In early 1976, he scored once in three league appearances for Waterford United. He also made a handful of appearances for Australian clubs Newcastle KB United,[24][25] Perth Azzurri[26][27] and Blacktown City.[28]

He joined Wigan Athletic as a director, and was briefly caretaker manager there in 1983. He then spent some time playing in South Africa.[29] He also built up several businesses in areas such as travel, jewellery and hampers, and ran soccer schools in the UK, the US, Canada, Australia and China. In 1984, he was invited to become member of the board of directors at Manchester United, partly because of his football knowledge and partly because it was felt that the club needed a "name" on the board after the resignation of Sir Matt Busby.[30] He remained a director of Manchester United as of 2018, and his continued presence was a factor in placating many fans opposed to the club's takeover by Malcolm Glazer.

Personal life and retirement

Charlton met his wife, Norma Ball, at an ice rink in Manchester in 1959 and they married in 1961. They have two daughters, Suzanne and Andrea. Suzanne was a weather forecaster for the BBC during the 1990s. They now have grandchildren, including Suzanne's son Robert, who is named in honour of his grandfather.

In 2007, while publicising his forthcoming autobiography, Charlton revealed that he had a long-running feud with his brother, Jack. They have rarely spoken since a falling-out between his wife Norma and his mother Cissie (who died on 25 March 1996 at the age of 83).[31] Bobby Charlton did not see his mother after 1992 as a result of the feud.[32]

Jack presented him with his BBC Sports Personality of the Year Lifetime Achievement Award on 14 December 2008. He said that he was 'knocked out' as he was presented the award by his brother. He received a standing ovation as he stood waiting for his prize.[33]

Charlton helped to promote Manchester's bids for the 1996 and 2000 Olympic Games and the 2002 Commonwealth Games, England's bid for the 2006 World Cup and London's successful bid for the 2012 Summer Olympics.[34] He received a knighthood in 1994 and was an Inaugural Inductee to the English Football Hall of Fame in 2002. On accepting his award, he commented: "I'm really proud to be included in the National Football Museum's Hall of Fame. It's a great honour. If you look at the names included I have to say I couldn't argue with them. They are all great players and people I would love to have played with." He is also the (honorary) president of the National Football Museum, an organisation about which he said "I can't think of a better museum anywhere in the world."

On 2 March 2009, Charlton was given the freedom of the city of Manchester. He stated: "I'm just so proud, it's fantastic. It's a great city. I have always been very proud of it."[35]

Charlton is involved in a number of charitable activities, including fund raising for cancer hospitals.[36] Charlton became involved in the cause of land mine clearance after visits to Bosnia and Cambodia[37] and supports the Mines Advisory Group as well as founding his own charity Find a Better Way which funds research into improved civilian landmine clearance.[38]

In January 2011, Charlton was voted the fourth-greatest Manchester United player of all time by the readers of Inside United and ManUtd.com, behind Ryan Giggs (who topped the poll), Eric Cantona and George Best.[39]

He is a member of the Laureus World Sports Academy.[40] On 6 February 2012 Charlton was taken to hospital after falling ill, and subsequently had a gallstone removed. This prevented him from collecting a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Laureus World Sports Awards.[41]

On 15 February 2016, Manchester United announced the South Stand of Old Trafford would be renamed in honour of Sir Bobby Charlton.[42] The unveiling took place at the home game against Everton on 3 April 2016.[43]

In October 2017, Charlton had a pitch named after him at St George's Park.[44]

In November 2020, it was revealed that Charlton had been diagnosed with dementia.[45]

In popular culture

- In the episode "Taking Liberties" of the sitcom Frasier, Daphne Moon (Jane Leeves) mentions that one of her uncles tried fanatically to get Charlton's autograph, "until Bobby cracked him over the head with a can of lager. Twelve stitches, and he still has the can!"[46]

- In the 2011 film United, centred on the successes of the Busby Babes and the decimation of the team in the Munich crash, Charlton was portrayed by actor Jack O'Connell.[47]

- In the episode "Munich Air Disaster" of the air crash documentary Mayday, he was interviewed as a survivor in the show, alongside Harry Gregg.

Career statistics

Club

| Club | Season | League | Cup | League Cup | Continental | Other | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | ||

| Manchester United | 1956–57 | First Division | 14 | 10 | 2 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 12 | |

| 1957–58 | 21 | 8 | 7 | 5 | — | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 16 | |||

| 1958–59 | 38 | 29 | 1 | 0 | — | — | — | 39 | 29 | |||||

| 1959–60 | 37 | 18 | 3 | 3 | — | — | — | 40 | 21 | |||||

| 1960–61 | 39 | 21 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 42 | 21 | ||||

| 1961–62 | 37 | 8 | 6 | 2 | — | — | — | 43 | 10 | |||||

| 1962–63 | 28 | 7 | 6 | 2 | — | — | — | 34 | 9 | |||||

| 1963–64 | 40 | 9 | 7 | 2 | — | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 54 | 15 | |||

| 1964–65 | 41 | 10 | 7 | 0 | — | 11 | 8 | — | 59 | 18 | ||||

| 1965–66 | 38 | 16 | 7 | 0 | — | 8 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 54 | 18 | |||

| 1966–67 | 42 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 44 | 12 | ||||

| 1967–68 | 41 | 15 | 2 | 1 | — | 9 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 53 | 20 | |||

| 1968–69 | 32 | 5 | 6 | 0 | — | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 48 | 7 | |||

| 1969–70 | 40 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 8 | 1 | — | — | 57 | 14 | ||||

| 1970–71 | 42 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 3 | — | — | 50 | 8 | ||||

| 1971–72 | 40 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 2 | — | — | 53 | 12 | ||||

| 1972–73 | 36 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | — | — | 41 | 7 | ||||

| Total | 606 | 199 | 78 | 19 | 24 | 7 | 45 | 22 | 5 | 2 | 758 | 249 | ||

| Preston North End | 1974–75 | Third Division | 38 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | — | — | 45 | 10 | ||

| Waterford United | 1975–76 | League of Ireland | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 4 | 1 | ||

| Career total | 647 | 208 | 83 | 20 | 27 | 8 | 45 | 22 | 5 | 2 | 807 | 260 | ||

International

| England senior team[48] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Apps | Goals |

| 1958 | 6 | 7 |

| 1959 | 7 | 5 |

| 1960 | 8 | 6 |

| 1961 | 9 | 6 |

| 1962 | 8 | 1 |

| 1963 | 10 | 6 |

| 1964 | 8 | 2 |

| 1965 | 5 | 2 |

| 1966 | 15 | 6 |

| 1967 | 4 | 2 |

| 1968 | 8 | 3 |

| 1969 | 9 | 1 |

| 1970 | 9 | 2 |

| Total | 106 | 49 |

Honours

Club

Source:[49]

- Manchester United

- Football League First Division (3): 1956–57, 1964–65, 1966–67

- FA Cup: 1962–63

- Charity Shield (4): 1956, 1957, 1965, 1967

- European Cup: 1967–68

- FA Youth Cup (3): 1953–54, 1954–55, 1955–56

International

Source:[49]

- England

- FIFA World Cup: 1966

- UEFA European Championship third place: 1968

- British Home Championship (10): 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1968, 1969, 1970

Individual

Source:[49]

- FWA Footballer of the Year: 1965–66

- FIFA World Cup Golden Ball: 1966

- FIFA World Cup All-Star Team (2): 1966, 1970

- Ballon d'Or: 1966

- Ballon d'Or (2nd place): 1967, 1968

- PFA Merit Award: 1974

- FWA Tribute Award: 1989

- FIFA World Cup All-Time Team: 1994

- Football League 100 Legends: 1998

- English Football Hall of Fame: 2002

- FIFA 100: 2004

- UEFA Golden Jubilee Poll: 14th

- PFA England League Team of the Century (1907 to 2007):

- BBC Sports Personality of the Year Lifetime Achievement Award: 2008

- UEFA President's Award: 2008[52]

- Laureus Lifetime Achievement Award: 2012

- FIFA Player of the Century:

- FIFA internet vote: 16th

- IFFHS vote: 10th

- World Soccer The Greatest Players of the 20th century: 12th[53]

- IFFHS Legends[54]

Orders and special awards

References

- Crick, Michael; Smith, David (1990). Manchester United: The Betrayal of a Legend. Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-31440-8.

- Charlton, Sir Bobby (2007). The Autobiography: My Manchester United Years. Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 0-7553-1619-3.

Notes

- "Robert CHARLTON". Companies House. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Barnes, Simon (8 October 2017). "What made Bobby Charlton the best footballer ever?". Radio Times. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- "Giggs nears Reds all-time record". BBC Sport. 3 May 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- "Bobby Charlton". britannica.com/eb. Retrieved 28 January 2006.

- "Bobby Charlton". Yahoo!. Retrieved 23 January 2006.

- "Manchester United Staff". 11v11.com. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1916-2007

- 1939 England and Wales Register

- Charlton 2007, p. 19

- Charlton 2007, p. 46

- White, John D.T. (29 May 2008). "January". The Official Manchester United Almanac (1st ed.). London: Orion Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7528-9192-7.

- Charlton 2007, p. 62

- Charlton 2007, p.70

- Crick and Smith (1990), pp. 100–101.

- "28 April 1973 League Division One vs Chelsea". aboutmanutd.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- "31 March 1973 League Division One vs Southampton". aboutmanutd.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- "World Cup 1958 Group D". Planet World Cup. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Profile". englandfc.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- "West Germany - England 3-2 aet (2-2,0-1)". Planet World Cup. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- England: The Official F.A History, Niall Edworthy, Virgin Publishers, 1997, ISBN 1-85227-699-1. p. 101

- "Wayne Rooney: England record is 'dream come true'". BBC Sport. 8 September 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- "Big Interview – John Bird". Leyland Guardian. 8 February 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- "Charlton wanted". Glasgow Herald. 22 August 1975. p. 24. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- "Fairfax Syndication Photo Print Sales and Content Licensing". newsstore.smh.com.au. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Looking at Newcastle's rocky football history". Theroar.com. 23 October 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- "footballwa.net: 1980 Competition Review". members.iinet.net.au. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- "The Superstars - Football West Hall of Fame - SportsTG". SportsTG. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- "Man United Legend Bobby Charlton At Blacktown City & Other One Game Wonders". Sabotagetimes.com. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- "Reviews". Soccer Through The Years. Archived from the original on 24 January 2003. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- Crick and Smith (1990), pp. 181–182.

- David Smith (27 August 2007). "Sir Bobby reopens the family feud". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- "Mother's Day special: Football's top 10 most important mothers". www.mirror.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014.

- "Sports Personality 2008: Charlton given BBC Lifetime award". BBC Sport. 14 December 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- "Charlton leads tributes to Banks". BBC News. 9 January 2006. Retrieved 28 January 2006.

- "Sir Bobby given freedom of city". BBC News. 2 March 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- "PNHS Press release, Sir Bobby's Hole in One For Christie's". Archived from the original on 21 November 2010.

- "Yean Maly, CAMBODIA: Sir Bobby Charlton and Tony Hawk fly in". Archived from the original on 10 February 2008.

- "Sir Bobby Charlton launches landmine research charity". BBC News. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- "Giggs United's Greatest". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 31 January 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "Academy Members". Laureus. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- "Charlton has minor surgery". Irish Independent.

- Hirst, Paul (15 February 2016). "Sir Bobby Charlton Stand: Manchester United announce plans to re-name South Stand at Old Trafford". The Independent. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- Valente, Allan (4 April 2016). "Manchester United rename stand in honour of Sir Bobby Charlton". Sky Sports (BSkyB). Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- Davis, Callum (2 October 2017). "England honour Sir Bobby Charlton with St George's Park training pitch". The Telegraph.

- "Sir Bobby Charlton: England World Cup winner diagnosed with dementia". BBC Sport. 1 November 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- "Frasier: Taking Liberties". IMDb. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Derby actor Jack O'Connell nets Bobby Charlton role". BBC News. 21 April 2011.

- "Robert "Bobby" Charlton - International Appearances". Rsssf.com. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- "Knight who led the charge for Ramsey's England". FIFA. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- "England Boys of '66 dominate your Team of the Century: 1907-1976". GiveMeFootball.com. Give Me Football. 28 August 2007. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- "Your overall Team of the Century: the world's greatest-ever XI revealed!". GiveMeFootball.com. Give Me Football. 6 September 2007. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- "UEFA President's Award". UEFA.com. 2 January 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- World Soccer: The 100 Greatest Footballers of All Time Archived 31 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 28 November 2015

- "IFFHS announce the 48 football legend players". IFFHS. 25 January 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "Sir Bobby Charlton awarded Japanese Order". Japan Football Association. 29 April 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bobby Charlton. |