Italy national football team

The Italy national football team (Italian: Nazionale di calcio dell'Italia) has officially represented Italy in international football since their first match in 1910. The squad is under the global jurisdiction of FIFA and is governed in Europe by UEFA—the latter of which was co-founded by the Italian team's supervising body, the Italian Football Federation (FIGC). Italy's home matches are played at various stadiums throughout Italy, and their primary training ground, Centro Tecnico Federale di Coverciano, is located at the FIGC technical headquarters in Coverciano, Florence.

| ||||

| Nickname(s) | Gli Azzurri (The Blues) La Nazionale (The National Team) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association | Italian Football Federation (Federazione Italiana Giuoco Calcio, FIGC) | |||

| Confederation | UEFA (Europe) | |||

| Head coach | Roberto Mancini | |||

| Captain | Giorgio Chiellini | |||

| Most caps | Gianluigi Buffon (176) | |||

| Top scorer | Luigi Riva (35) | |||

| Home stadium | Various | |||

| FIFA code | ITA | |||

| ||||

| FIFA ranking | ||||

| Current | 10 | |||

| Highest | 1 (November 1993, February 2007, April–June 2007, September 2007) | |||

| Lowest | 21 (August 2018) | |||

| First international | ||||

(Milan, Italy; 15 May 1910) | ||||

| Biggest win | ||||

(Brentford, England; 2 August 1948) | ||||

| Biggest defeat | ||||

(Budapest, Hungary; 6 April 1924) | ||||

| World Cup | ||||

| Appearances | 18 (first in 1934) | |||

| Best result | Champions (1934, 1938, 1982, 2006) | |||

| European Championship | ||||

| Appearances | 9 (first in 1968) | |||

| Best result | Champions (1968) | |||

| Confederations Cup | ||||

| Appearances | 2 (first in 2009) | |||

| Best result | Third place (2013) | |||

Medal record

| ||||

| Website | FIGC.it (in Italian) (in English) | |||

Italy is one of the most successful national teams in the history of the World Cup, having won four titles (1934, 1938, 1982, 2006) and appearing in two other finals (1970, 1994), reaching a third place (1990) and a fourth place (1978). In 1938, they became the first team to defend their World Cup title, and due to the outbreak of World War II, retained the title for a further 12 years. Italy had also previously won two Central European International Cups (1927–30, 1933–35). Between its first two World Cup victories, Italy won the Olympic football tournament (1936). After the majority of the team was killed in a plane crash in 1949, the team did not advance past the group stage of the following two World Cup tournaments, and also failed to qualify for the 1958 edition—failure to qualify for the World Cup would not happen again until the 2018 edition. Italy returned to form by 1968, winning a European Championship (1968), and after a period of alternating unsuccessful qualification rounds in Europe, later appeared in two other finals (2000, 2012). Italy's highest finish at the FIFA Confederations Cup was in 2013, where the squad achieved a third-place finish.

The team is known as gli Azzurri (the Blues). Savoy blue is the common colour of the national teams representing Italy, as it is the traditional paint of the royal House of Savoy, which reigned over the Kingdom of Italy from 1860 to 1946. The national team is also known for its long-standing rivalries with other top footballing nations, such as those with Brazil, Croatia, France, Germany and Spain. In the FIFA World Rankings, in force since August 1993, Italy has occupied the first place several times, in November 1993 and during 2007 (February, April–June, September), with its worst placement in August 2018 in 21st place.

History

1910–1938: Origins and first two World Cups

The team's first match was held in Milan on 15 May 1910. Italy defeated France by a score of 6–2, with Italy's first goal scored by Pietro Lana.[2][3][4] The Italian team played with a (2–3–5) system and consisted of: De Simoni; Varisco, Calì; Trerè, Fossati, Capello; Debernardi, Rizzi, Cevenini I, Lana, Boiocchi. First captain of the team was Francesco Calì.[5]

The first success in an official tournament came with the bronze medal in 1928 Summer Olympics, held in Amsterdam. After losing the semi-final against Uruguay, an 11–3 victory against Egypt secured third place in the competition. In the 1927–30 and 1933–35 Central European International Cup, Italy achieved the first place out of five Central European teams, topping the group with 11 points in both editions of the tournament.[6][7] Italy would also later win the gold medal at the 1936 Summer Olympics with a 2–1 victory in extra time in the gold medal match over Austria on 15 August 1936.[8]

After declining to participate in the inaugural World Cup (1930, in Uruguay) the Italy national team won two consecutive editions of the tournament in 1934 and 1938, under the direction of coach Vittorio Pozzo and the performance of Giuseppe Meazza, who is considered one of the best Italian football players of all time by some.[9][10] Italy hosted the 1934 World Cup, and played their first ever World Cup match in a 7–1 win over the United States in Rome. Italy defeated Czechoslovakia 2–1 in extra time in the final in Rome, with goals by Raimundo Orsi and Angelo Schiavio to achieve their first World cup title in 1934. They achieved their second title in 1938 in a 4–2 defeat of Hungary, with two goals by Gino Colaussi and two goals by Silvio Piola in the World Cup that followed. Rumour has it, before the 1938 finals fascist Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini was to have sent a telegram to the team, saying "Vincere o morire!" (literally translated as "Win or die!"). However, no record remains of such a telegram, and World Cup player Pietro Rava said, when interviewed, "No, no, no, that's not true. He sent a telegram wishing us well, but no never 'win or die'."[11]

1946–1966: Post-World War II

In 1949, 10 of the 11 players in the team's initial line-up were killed in a plane crash that affected Torino, winners of the previous five Serie A titles. Italy did not advance further than the first round of the 1950 World Cup, as they were weakened severely due to the air disaster. The team had travelled by boat rather than by plane, fearing another accident.[12]

In the World Cup finals of 1954 and 1962, Italy failed to progress past the first round, and did not qualify for the 1958 World Cup due to a 2–1 defeat to Northern Ireland in the last match of the qualifying round. Italy did not take part in the first edition of the European Championship in 1960 (then known as the European Nations Cup), and was knocked out by the Soviet Union in the first round of the 1964 European Nations' Cup qualifying.

Their participation in the 1966 World Cup was ended by a 0–1 defeat at the hands of North Korea. Despite being the tournament favourites, the Azzurri, whose 1966 squad included Gianni Rivera and Giacomo Bulgarelli, were eliminated in the first round by the semi-professional North Koreans. The Italian team was bitterly condemned upon their return home, while North Korean scorer Pak Doo-ik was celebrated as the David who killed Goliath. Upon Italy's return home, furious fans threw fruit and rotten tomatoes at their transport bus at the airport.[13][14]

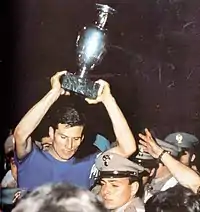

1968–1974: European champions and World Cup runners-up

In 1968, Italy participated in their first European Championship, hosting the European Championship and winning their first major competition since the 1938 World Cup, beating Yugoslavia in Rome for the title. The match is the only European Championship or World Cup final to go to a replay.[15] After extra time the final ended in a 1–1 draw, and in the days before penalty shootouts, the rules required the match to be replayed a few days later. Italy won the replay 2–0 (with goals from Luigi Riva and Pietro Anastasi) to take the trophy.

In the 1970 World Cup, exploiting the performances of European champions' players like Giacinto Facchetti, Gianni Rivera and Luigi Riva and with a new centre-forward Roberto Boninsegna, the team were able to come back to a World Cup final match after 32 years. They reached this result after one of the most famous matches in football history—the "Game of the Century", the 1970 World Cup semifinal between Italy and Germany that Italy won 4–3 in extra time, with five of the seven goals coming in extra time.[16] They were later defeated by Brazil in the final 4–1. The cycle of international successes ended in the 1974 World Cup, when the team was eliminated by Grzegorz Lato's Polish team in the first round.

1978–1986: Third World Cup generation

In the 1978 FIFA World Cup in Argentina, a new generation of Italian players, the most famous being Paolo Rossi, came to the international stage. Italy was the only team in the tournament to beat the eventual champions and host team Argentina. Second-round games against West Germany (0–0), Austria (1–0) and Netherlands (1–2) led Italy to the third-place final, where the team was defeated by Brazil 2–1. In the match that eliminated Italy from the tournament against the Netherlands, Italian goalkeeper Dino Zoff was beaten by a long-distance shot from Arie Haan, and Zoff was criticized for the defeat.[17] Italy hosted the 1980 UEFA European Football Championship, the first edition to be held between eight teams instead of four,[18] automatically qualifying for the finals as hosts. After two draws with Spain and Belgium and a narrow 1–0 win over England, Italy were beaten by Czechoslovakia in the third-place match on penalties 9–8 after Fulvio Collovati missed his kick.

After a scandal in Serie A where some National team players such as Paolo Rossi[19] were prosecuted and suspended for match fixing and illegal betting, the Azzurri qualified for the second round of the 1982 World Cup after three uninspiring draws against Poland, Peru and Cameroon. Having been loudly criticized, the Italian team decided on a press black-out from then on, with only coach Enzo Bearzot and captain Dino Zoff appointed to speak to the press.

Italy's regrouped in the second round group, a group of death with Argentina and Brazil. In the opener, Italy prevailed 2–1 over Argentina, with Italy's goals, both left-footed strikes, were scored by Marco Tardelli and Antonio Cabrini. After Brazil defeated Argentina 3–1, Italy needed to win in order to advance to the semi-finals. Twice Italy went in the lead with Paolo Rossi's goals, and twice Brazil came back. When Falcão scored to make it 2–2, Brazil would have been through on goal difference, but in the 74th minute Rossi scored the winning goal, for a hat-trick, in a crowded penalty area to send Italy to the semifinals after one of the greatest games in World Cup history.[20][21][22] Italy then progressed to the semi-final where they defeated Poland with two goals from Rossi.

In the final, Italy met West Germany, who had advanced by a penalty shootout victory against France. The first half ended scoreless, after Antonio Cabrini missed a penalty awarded for a Hans-Peter Briegel foul on Bruno Conti. In the second half Paolo Rossi again scored the first goal, and while the Germans were pushing forward in search of an equaliser, Marco Tardelli and substitute Alessandro Altobelli finalised two contropiede counterattacks to make it 3–0. Paul Breitner scored home West Germany's consolation goal seven minutes from the end.[23]

Tardelli's cry, "Gol! Gol!" was one of the defining images of Italy's 1982 World Cup triumph.[24] Paolo Rossi won the Golden Boot with six goals as well as the Golden Ball Award for the best player of the tournament,[25] and 40-year-old captain-goalkeeper Dino Zoff became the oldest player to win the World Cup.[26]

However, Italy failed to qualify for the 1984 European Championship.[27][28] Italy then entered as reigning champions in the 1986 World Cup[29][30][31] but were eliminated by reigning European Champions, France, in the round of 16.[32]

1988–1994: World Cup runners-up

In 1986, Azeglio Vicini was appointed as new head coach, replacing Bearzot.[33] New coach conceded a chance to young players, such as Ciro Ferrara and Gianluca Vialli:[34] Sampdoria striker scored goals that gave Italy 1988 European Championship pass.[35] He was also shown like Altobelli's possibly successor, having his same goal attitude.[36] Both forwards stroke the target in Germany, where Soviet Union defeated azzurri in semi-finals.[37]

Italy hosted the World Cup for the second time in 1990. The Italian attack featured talented forwards Salvatore Schillaci and a young Roberto Baggio. Italy played nearly all of their matches in Rome and did not concede a single goal in their first five matches, however, they lost the semi-final in Naples to defending champion Argentina. Argentinian player Maradona, who played for Napoli, made comments prior to the game pertaining to the North–South inequality in Italy and the risorgimento, asking Neapolitans to root for Argentina in the game.[38] Italy lost 4–3 on penalty kicks following a 1–1 draw after extra time. Schillaci's first-half opener was equalised in the second half by Claudio Caniggia's header for Argentina. Aldo Serena missed the final penalty kick with Roberto Donadoni also having his penalty saved by goalkeeper Sergio Goycochea. Italy went on to defeat England 2–1 in the third-place match in Bari, with Schillaci scoring the winning goal on a penalty to become the tournament's top scorer with six goals. Italy then failed to qualify for the 1992 European Championship. In November 1993, FIFA ranked Italy first in the FIFA World Rankings for their first time since the ranking system was introduced in December 1992.[39]

At the 1994 World Cup in the United States, Italy lost the opening match against Ireland 0–1 at the Giants Stadium near New York City. After a 1–0 win against Norway in New York City and a 1–1 draw with Mexico at the RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C., Italy advanced from Group E based on goals scored among the four teams tied on points. During their round of 16 match at the Foxboro Stadium near Boston, Italy was down 0–1 late against Nigeria, but Baggio rescued Italy with an equaliser in the 88th minute and a penalty in extra time to take the win.[40] Baggio scored another late goal against Spain at their quarter-final match in Boston to seal a 2–1 win and two goals against Bulgaria in their semi-final match in New York City for another 2–1 win.[41][42]

In the final, which took place in Los Angeles's Rose Bowl stadium 2,700 miles (4,320 km) and three time zones away from the Atlantic Northeast part of the United States where they had played all their previous matches, Italy, who had 24 hours less rest than Brazil, played 120 minutes of scoreless football, taking the match to a penalty shootout, the first time a World Cup final was settled in a penalty shootout.[43] Italy lost the subsequent shootout 3–2 after Baggio, who had been playing with the aid of a pain-killer injection[44] and a heavily bandaged hamstring,[45][46] missed the final penalty kick of the match, shooting over the crossbar.[47][48]

1996–2000: European Championship runners-up

Italy did not progress beyond the group stage at the finals of Euro 1996. Having defeated Russia 2–1 but losing to the Czech Republic by the same score, Italy required a win to be sure of progressing. Gianfranco Zola failed to convert a decisive penalty in a 0–0 draw against Germany,[49] who eventually won the tournament. During the qualifying campaign for the 1998 World Cup, Italy drew 0–0 to England on the last day of Group 2 matches as Italy finished in second place, one point behind England. Italy were then required to go through the play-off against Russia, advancing 2–1 on aggregate on 15 November 1997 with the winner coming from Pierluigi Casiraghi.[50] In the final tournament, Italy found themselves in another critical shootout for the third World Cup in a row. The Italian side, where Alessandro Del Piero and Baggio renewed the controversial staffetta ("relay") between Mazzola and Rivera from 1970, held the eventual World Champions and host team France to a 0–0 draw after extra time in the quarter-finals, but lost 4–3 in the shootout. With two goals scored in this tournament, Baggio is still the only Italian player to have scored in three different FIFA World Cup editions.[51]

In the Euro 2000, another shootout decided Italy's fate but this time in their favour when defeating the co-hosts the Netherlands in the semi final. Italian goalkeeper Francesco Toldo saved one penalty during the match and two in the shootout, while the Dutch players missed one other penalty during the match and one during the shootout with a rate of one penalty scored out of six attempts. Emerging star Francesco Totti scored his penalty with a cucchiaio ("spoon") chip. Italy finished the tournament as runners-up, losing the final 2–1 against France (to a golden goal in extra time) after conceding les Bleus equalising goal just 30 seconds before the expected end of injury time (93rd minute).[52] After the defeat, coach Dino Zoff resigned in protest after being criticized by Milan club president and politician Silvio Berlusconi.[53]

2000–2004: Trapattoni Era

In the 2002 World Cup, a 2–0 victory against Ecuador with two Christian Vieri goals was followed by a series of controversial matches. During the match against Croatia, two goals were disallowed resulting in a 2–1 defeat for Italy. Despite two goals being ruled for borderline offsides, a late headed goal from Alessandro Del Piero helped Italy to a 1–1 draw with Mexico proving enough to advance to the knockout stages. However, co-host country South Korea eliminated Italy in the round of 16 by a score of 2–1. The game was highly controversial with members of the Italian team, most notably striker Francesco Totti and coach Giovanni Trapattoni, suggesting a conspiracy to eliminate Italy from the competition.[54] Trapattoni even obliquely accused FIFA of ordering the official to ensure a Korean victory so that one of the two host nations would remain in the tournament.[55] The most contentious decisions by the game referee Byron Moreno were an early penalty awarded to South Korea (saved by Buffon), a golden goal by Damiano Tommasi ruled offside, and the sending off of Totti after being presented with a second yellow card for an alleged dive in the penalty area.[56] FIFA President Sepp Blatter stated that the linesmen had been a "disaster" and admitted that Italy suffered from bad offside calls during the group matches, but he denied conspiracy allegations. While questioning Totti's sending off by Moreno, Blatter refused to blame Italy's loss entirely on the referees, stating: "Italy's elimination is not only down to referees and linesmen who made human not premeditated errors ... Italy made mistakes both in defense and in attack."[57]

A three-way five point tie in the group stage of the 2004 European Championship left Italy as the "odd man out", as they failed to qualify for the quarter finals after finishing behind Denmark and Sweden on the basis of number of goals scored in matches among the tied teams. Italy's winning goal scored during stoppage time giving them a 2–1 victory over Bulgaria by Antonio Cassano proved futile, ending the team's tournament.

2006: Fourth World Cup title

The summer of 2004 marked the choice, by FIGC, to appoint Marcello Lippi for Italy's bench.[58] He made his debut in an upset 2–0 defeat in Iceland[59] but then managed to qualify for 2006 World Cup.[60][61] Italy's campaign in the tournament hosted by Germany was accompanied by open pessimism[62] due to the controversy caused by the 2006 Serie A scandal,[63] however these negative predictions were then refuted, as the Azzurri eventually won their fourth World Cup.

Italy won their opening game against Ghana 2–0, with goals from Andrea Pirlo (40th minute) and substitute Vincenzo Iaquinta (83rd minute). The team performance was judged the best among the opening games by FIFA President Sepp Blatter.[64]

The second match was a less convincing 1–1 draw with United States, with Alberto Gilardino's diving header equalized by a Cristian Zaccardo own goal.[65] After the equaliser, midfielder Daniele De Rossi and the United States's Pablo Mastroeni and Eddie Pope were sent off, leaving only nine men on the field for nearly the entirety of the second half, but the score remained unchanged despite a controversial decision when Gennaro Gattuso's shot was deflected in but disallowed because of an offside ruling. The same happened at the other end when U.S. winger DaMarcus Beasley's goal was not given due to teammate Brian McBride being ruled offside. De Rossi was suspended for four matches for elbowing McBride in the face and only returned for the final match.

Italy finished first in Group E with a 2–0 win against the Czech Republic, with goals from defender Marco Materazzi (26th minute) and striker Filippo Inzaghi (87th minute), advancing to the Round of 16 in the knockout stages, where they faced Australia. In this match, Materazzi was controversially sent off early in the second half (53rd minute) after an attempted two-footed tackle on Australian midfielder Marco Bresciano. In stoppage time a controversial penalty kick was awarded to the Azzurri when referee Luis Medina Cantalejo ruled that Lucas Neill fouled Fabio Grosso. Francesco Totti converted into the upper corner of the goal past Mark Schwarzer for a 1–0 win.[66]

In the quarter-finals, Italy beat Ukraine 3–0. Gianluca Zambrotta opened the scoring early (in the sixth minute) with a left-footed shot from outside the penalty area after a quick exchange with Totti created enough space. Luca Toni added two more goals in the second half (59th and 69th minute), as Ukraine pressed forward but were not able to score, hitting the crossbar and requiring several saves from Gianluigi Buffon and a goal-line clearance from Zambrotta. Afterwards, manager Marcello Lippi dedicated the victory to former Italian international Gianluca Pessotto, who was in the hospital recovering from an apparent suicide attempt.[67]

In the semi-finals, Italy beat hosts Germany 2–0 with the two goals coming in the last two minutes of extra time. After a back-and-forth half-hour of extra time during which Alberto Gilardino and Gianluca Zambrotta struck the post and the crossbar respectively, Fabio Grosso scored in the 119th minute after a disguised Andrea Pirlo pass found him open in the penalty area for a bending left-footed shot into the far corner past German goalkeeper Jens Lehmann's dive. Substitute striker Alessandro Del Piero then sealed the victory by scoring with the last kick of the game at the end of a swift counterattack by Cannavaro, Totti and Gilardino.[68]

The Azzurri won their fourth World Cup, defeating their long-time rivals France in Berlin, on 9 July, 5–3 on penalty kicks after a 1–1 draw at the end of extra time in the final. French captain Zinedine Zidane opened the scoring in the seventh minute with a chipped penalty kick, awarded for a controversial foul by Materazzi on Florent Malouda. Twelve minutes later, a header by Materazzi from a corner kick by Pirlo brought Italy even. In the second half, a potential winning goal by Toni was disallowed for a very close offside call by linesman Luc La Rossa. In the 110th minute, Zidane (playing in the last match of his career) was sent off by referee Horacio Elizondo for headbutting Materazzi in the chest after a verbal exchange;[69] Italy then won the penalty shootout 5–3, with the winner scored by Grosso; the crucial penalty miss from the French being David Trezeguet's, the same player who scored the golden goal for France in the Euro 2000. Trezeguet's attempt hit the crossbar, then shot down after its impact, and just stayed ahead of the line.[70]

Ten different players scored for Italy in the tournament, and five goals out of twelve were scored by substitutes, while four goals were scored by defenders. Seven players — Gianluigi Buffon, Fabio Cannavaro, Gianluca Zambrotta, Andrea Pirlo, Gennaro Gattuso, Francesco Totti and Luca Toni — were named to the 23-man tournament All Star Team.[71] Buffon also won the Lev Yashin Award, given to the best goalkeeper of the tournament; he conceded only two goals in the tournament's seven matches, the first an own goal by Zaccardo and the second from Zidane's penalty kick in the final, and remained unbeaten for 460 consecutive minutes.[72] In honour of Italy winning the FIFA World Cup for a fourth time, all members of the World Cup-winning squad were awarded the Italian Order of Merit of Cavaliere Ufficiale.[73][74]

2006–2010: Post-World Cup decline

Marcello Lippi, who had announced his resignation three days after the World Cup triumph, was replaced by Roberto Donadoni as the new coach of the Azzurri.[75] Italy played in the 2008 UEFA European Football Championship qualifying Group B, along with France. Italy won the group, with France being the runner-up. On 14 February 2007, Italy climbed to first in the FIFA World Rankings from second, with a total of 1,488 points, 37 points ahead of second ranked Argentina. This was the second time in the Azzurri's history that it had been ranked in first place, the first time being in 1993; they would also be ranked first several times throughout 2007, also in April–June and September.[39][76]

In Euro 2008, the Azzurri lost 3–0 to the Netherlands. The following game against Romania ended 1–1, with a goal by Christian Panucci that came only one minute after Romania's Adrian Mutu capitalized on a mistake by Gianluca Zambrotta to give Romania the lead.[77] The result was preserved by Gianluigi Buffon who saved a penalty kick from Mutu in the 80th minute.[77]

The final group game against France, a rematch of the 2006 World Cup Final, was a 2–0 Italy win. Andrea Pirlo scored from the penalty spot after a foul and red card for France defender Eric Abidal, and later a free kick by Daniele De Rossi took a deflection resulting Italy's second goal. Romania, entering the day a point ahead of the Italians in Group C, lost to the Netherlands 2–0, allowing Italy to pass into the quarter finals against eventual champions Spain, where they lost 2–4 on penalties after a 0–0 draw after 120 minutes. Within a week after the game, Roberto Donadoni's contract was terminated and Marcello Lippi was rehired as coach.[78]

Italy qualified for their first ever FIFA Confederations Cup held in South Africa in June 2009 by virtue of winning the 2006 World Cup. They won their opening match of the tournament by a score of 3–1 against the United States, but subsequent defeats to Egypt (0–1) and Brazil (0–3) meant that they only finished third in the group on goals scored, and were eliminated.

The national football team of Italy qualified for the 2010 FIFA World Cup after playing home games at Stadio Friuli, Stadio Via del Mare, Stadio San Nicola, Stadio Olimpico di Torino and Stadio Ennio Tardini. In October 2009, they achieved qualification after drawing with the Republic of Ireland 2–2. On 4 December 2009, the draw for the World Cup was made: Italy would be in Group F alongside three underdog teams: Paraguay, New Zealand and Slovakia.

At the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, reigning champions Italy were unexpectedly eliminated in the first round, finishing last place in their group. After being held to 1–1 draws by Paraguay and New Zealand, they suffered a 3–2 loss to Slovakia.[79] It was the first time Italy failed to win a single game at a World Cup finals tournament, and in doing so became the third nation to be eliminated in the first round while holding the World Cup crown; the first being Brazil in 1966 and the second France in 2002.[80] Coincidentally, France who had been Italy's adversaries and the losing finalist in the 2006 World Cup, were also eliminated without winning a game in the first round in South Africa, making it the first time ever that neither finalist of the previous edition were able to reach the second round.[81]

2010–2014: European Championship runners-up

Marcello Lippi stepped down after Italy's World Cup campaign and was replaced by Cesare Prandelli, although Lippi's successor had already been announced before the tournament.[82] Italy began their campaign with Prandelli with a 1–0 loss to the Ivory Coast in a friendly match.[83] Then, during a Euro 2012 qualifier, Italy came back from behind to defeat Estonia 2–1. In the next Euro qualifier, Italy dominated the Faroe Islands 5–0. Italy then tied 0–0 with Northern Ireland. Five days later, Italy played Serbia; however, Serbian fans in Stadio Luigi Ferraris began to riot, throwing flares and shooting fireworks onto the pitch, subsequently causing the abandonment of the game.[84] Upon UEFA Disciplinary Review, Italy was awarded a 3–0 victory that propelled them to the top of their group.[85] In their first match of 2011, Italy drew 1–1 a friendly with Germany at Dortmund, in the same stadium where they beat Germany 2–0 to advance to the final of the 2006 World Cup. In March 2011, Italy won 1–0 over Slovenia to again secure its spot at the top of the qualification table. They then defeated Ukraine 2–0 in a friendly, despite being reduced to ten men for the late stages of the match. With their 3–0 defeat of Estonia in another Euro 2012 qualifier, Prandelli's Italy secured the table lead and also achieved 9 undefeated games in a row since their initial debacle. The streak was ended on 7 June 2011 by Trapattoni's current charges, the Republic of Ireland, with Italy losing 0–2 in a friendly in Liège.

At the beginning of the second season under coach Prandelli, on 10 August 2011, Italy defeated the reigning world champions Spain for 2–1 in a friendly match played in Bari's Stadio San Nicola, but lost in a friendly to the United States, 1–0, on home soil on 29 February 2012.[86]

Italy started their Euro 2012 campaign with a 1–1 draw to current reigning European and World champions Spain. In the following match, they draw 1–1 against Croatia. They finished second in their group behind Spain by beating the Republic of Ireland 2–0, which earned them a quarter-final match against the winners of group D, England. After a mostly one-sided affair in which Italy failed to take their chances, they managed to beat England on penalty kicks, even though they were down early in the shootout. A save by goalkeeper Gianluigi Buffon put them ahead after a chip shot from Andrea Pirlo. Prandelli's side won the shootout 4–2.[87][88]

In their next game, the first semi-final of the competition, they faced Germany team who were tipped by many to be the next European champions.[89][90][91][92][93] However, two first-half goals by Mario Balotelli saw Germany sent home, and the Italians went through to the finals to face the title defenders Spain.

In the final, however, they were unable to repeat their earlier performance against Spain, falling 4–0 to lose the championship. Prandelli's men were further undone by the string of injuries which left them playing with ten men for the last half-hour, as substitute Thiago Motta was forced to go off after all three substitutions had been made.[94]

During the 2013 Confederations Cup in Brazil, Italy started in a group with Mexico, Japan and Brazil. After beating Mexico 2–1 and Japan 4–3, Italy eventually lost their final group game against tournament hosts Brazil 4–2. Italy then faced Spain in the semi-finals, in a rematch of the Euro 2012 final. Italy lost 7–6 (0–0 after extra time) in a penalty shoot-out after Leonardo Bonucci failed to score his kick.[95] Prandelli was praised for his tactics against the current World Cup and European champions.[96] Italy was then able to win the match for the third place by defeating Uruguay with the penalty score of 5–4 (2–2 after extra time).

Italy was drawn in UEFA Group B for the 2014 World Cup qualification campaign. They won the qualifying group without losing a match. Despite this successful run they were not seeded in pot 1 for the final seeding. In December 2013, Italy was drawn in Group D against Costa Rica, England and Uruguay. In its first match, Italy defeated England 2–1. However, in the second group stage match, underdogs Costa Rica beat the Italians 1–0.[97] In Italy's last group match, they were knocked out by Uruguay 1–0, due in part to two controversial calls from referee Marco Antonio Rodríguez (Mexico): in the 59th minute, midfielder Claudio Marchisio was sent off for a questionable tackle.[98] Later in the 80th minute, with the teams knotted at 0–0 which would have sent Italy to the next round, Uruguayan striker Luis Suárez bit defender Giorgio Chiellini on the shoulder but was not sent off.[99][100] Uruguay went on to score moments later in the 81st minute with a Diego Godín header from a corner kick, winning the game 1–0 and eliminating Italy. This marked Italy's second consecutive failure to reach the round of 16 at the World Cup finals. Shortly after this loss, coach Cesare Prandelli resigned.[101]

2014–2016: Euro 2016 campaign

The successful former Juventus manager Antonio Conte was selected to replace Cesare Prandelli as coach after the 2014 World Cup. Conte's debut as manager was against 2014 World Cup semi-finalists the Netherlands, in which Italy won 2–0. Italy's first defeat under Conte came ten games in to his empowerment from a 1–0 international friendly loss against Portugal on 16 June 2015.[102] On 10 October 2015, Italy qualified for Euro 2016, courtesy of a 3–1 win over Azerbaijan;[103] the result meant that Italy had managed to go 50 games unbeaten in European qualifiers.[104] Three days later, with a 2–1 win over Norway, Italy topped their Euro 2016 qualifying group with 24 points; four points clear of second placed Croatia.[105] However, with a similar fate to the 2014 World Cup group stage draw, Italy were not top seeded into the first pot. This had Italy see a draw with Belgium, Sweden and the Republic of Ireland in Group E.[106]

On 4 April 2016, it was announced that Antonio Conte would step down as Italy coach after Euro 2016 to become head coach of English club Chelsea at the start of the 2016–17 Premier League season.[107] The 23-man squad, which was initially criticized by many fans and members of the media for its tactics and level of quality,[108] saw notable absences with Andrea Pirlo and Sebastian Giovinco controversially left out[109] and Claudio Marchisio and Marco Verratti omitted due to injury.[110][111] Italy opened Euro 2016 with a 2–0 victory over Belgium on 13 June.[112] Italy qualified for the round of 16 with one game to spare on 17 June with a lone goal by Éder for the victory against Sweden; the first time they won the second group game in a major international tournament since Euro 2000.[113] Italy also finished top of the group for the first time in a major tournament since the 2006 World Cup.[114] Italy defeated reigning European champions Spain 2–0 in the round of 16 match on 27 June.[115] Italy then faced off against the reigning World champions, rivals Germany, in the quarter-finals. Mesut Özil opened the scoring in the 65th minute for Germany, before Leonardo Bonucci converted a penalty in the 78th minute for Italy. The score remained 1–1 after extra time and Germany beat Italy 6–5 in the ensuing penalty shoot-out. It was the first time Germany overcame Italy in a major tournament, however, since the win occurred on penalties, it is statistically considered a draw.[116][117]

Failure to qualify for 2018 World Cup

For the 2018 FIFA World Cup qualification Italy were placed into the second pot due to being in 17th place in the FIFA World Rankings at the time of the group draws; Italy were drawn with Spain from pot one on 25 July 2015.[118] After Conte's planned departure following Euro 2016, Gian Piero Ventura took over as manager for the team, on 18 July 2016, signing a two-year contract.[119] His first match at the helm was a friendly against France, held at the Stadio San Nicola on 1 September, which ended in a 3–1 loss.[120] Four days later, he won his first competitive match in charge of Italy, the team's opening 2018 FIFA World Cup qualifier against Israel at Haifa, which ended in a 3–1 victory for Italy.[121]

After Italy won all of their qualifying matches except for a 1–1 draw at home to Macedonia, as well as a 1–1 draw with Spain at home on 6 October 2016, and a 3–0 loss away to Spain on 2 September 2017, Italy finished in Group G in second place, five points behind Spain.[122][123] Italy were then required to go through the play-off against Sweden. After a 1–0 aggregate loss to Sweden, on 13 November 2017, Italy failed to qualify for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, the first time they failed to qualify for the World Cup since 1958.[124] Immediately following the match, veterans Giorgio Chiellini, Andrea Barzagli, Daniele De Rossi and captain Gianluigi Buffon all declared their retirement from the national team.[125][126][127][128][129] On 15 November 2017, Ventura was dismissed as head coach[130] and on 20 November 2017, Carlo Tavecchio resigned as president of the Italian Football Federation.[131][132]

2018–present: Resurgence with Mancini

On 5 February 2018, the Italy U21 manager Luigi Di Biagio was appointed as the caretaker manager of the senior team.[133] On 17 March 2018, despite the initial decision to retire by veterans Buffon and Chiellini, they were both called up for Italy's March 2018 friendlies by caretaker manager Di Biagio.[134] Following the March friendlies against Argentina and England in which Italy were defeated and drew respectively, on 12 April 2018, Italy dropped six places to their lowest FIFA World Ranking at the time, to 20th place.[135] On 14 May 2018, Roberto Mancini was announced as the new manager.[136] On 28 May 2018, Italy won their first match under Mancini, a 2–1 victory in a friendly over Saudi Arabia.[137] On 16 August 2018, in the FIFA World Ranking that followed the 2018 World Cup, Italy dropped two places to their lowest ever ranking, to 21st place.[138] On 7 September 2018, Italy participated in the inaugural UEFA Nations League, drawing their first match of the tournament against Poland in Bologna with a score of 1–1.[139]

On 12 October 2019, Italy qualified for Euro 2020 with three matches to spare after a 2–0 home win over Greece.[140] On 18 November, Italy finished Group J with ten wins in all ten of their matches, becoming only the sixth national side to qualify for a European Championship with a 100 per cent record, and the seventh instance, after France (1992 and 2004), Czech Republic (2000), Germany, Spain (both 2012) and England (2016).[141]

On 17 March 2020, UEFA confirmed that Euro 2020 had been postponed by one year in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe.[142] On 18 November 2020, with a 2–0 away win over Bosnia and Herzegovina, Italy finished first in their 2020–21 UEFA Nations League group and qualified for the Finals of the tournament.[143][144]

Team image

Kits, colours and badges

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Italy national football team kits. |

The first shirt worn by the Italy national team, in its debut against France on 15 May 1910, was white. The choice of colour was due to the fact that a decision about the appearance of the kit had not yet been made, so it was decided not to have a colour, which was why white was chosen.[145] After two games, for a friendly against Hungary in Milan on 6 January 1911, the white shirt was replaced by a blue jersey (specifically savoy azure) — blue being the border colour of the royal House of Savoy crest used on the flag of the Kingdom of Italy (1861-1946); the shirt was accompanied by white shorts and black socks (which later became blue).[145] The team later became known as gli Azzurri (the Blues).[145][146][147]

In the 1930s, Italy wore a black kit, ordered by the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini. The black kit debuted on 17 February 1935 in a friendly against France at the Stadio Nazionale PNF in Rome.[148] A blue shirt, white shorts and black socks were, however, worn at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin the following year. At the 1938 FIFA World Cup in France, the all-black kit was worn once (in the match against France).[149]

After World War II, the fascist regime fell and the monarchy was abolished in 1946. The same year saw the birth of the Italian Republic, and the blue-and-white kit was reinstated. The cross of the former Royal House of Savoy was removed from the flag of Italy, and consequently from the national team's badge, now consisting solely of the Tricolore. For the 1954 FIFA World Cup, the country's name in Italian, "ITALIA", was placed above the tricolour shield, and for the 1982 FIFA World Cup, "FIGC", the abbreviation of the Italian Football Federation, was incorporated into the badge.[145]

In 1983, to celebrate the victory at the World Cup of the previous year, three gold stars replaced the word "ITALIA" above the tricolour, representing their three World Cup victories until that point. And in 1984, a round emblem was launched, featuring the three stars, the inscriptions "ITALIA" and "FIGC", and the tricolour.[145]

The first known kit manufacturer was Adidas in 1974. Since 2003, the kit has been made by Puma.[145] Since the 2000s, an all-blue uniform including blue shorts has occasionally been used, particularity in international tournaments.[145] After Italy's 2006 World Cup victory, a fourth star was added to the tricolour badge.

Kit suppliers

| Kit supplier | Period |

|---|---|

| None | 1910–1974 |

| 1974–1978 | |

| 1978–1979 | |

| 1979–1984 | |

| 1984–1985 | |

| 1985–1994 | |

| 1994–1999 | |

| 1999–2003 | |

| 2003–present |

Rivalries

.jpg.webp)

Italy has five main rivalries with other top footballing nations.

- Their rivalry with Brazil, known as the Clásico Mundial in Spanish or the World Derby in English,[150] is between two of the most successful football nations in the world, having achieved nine World Cups between the two countries. Since their first match at 1938 World Cup, they have played against each other a total of five times in the World Cup, most notably in the 1970 World Cup Final and the 1994 World Cup final in which Brazil won 4–1 and 3–2 on penalties after a goalless draw respectively.[151]

- Their rivalry with Croatia, also known as the Derby Adriatico or Adriatic Derby, named after the Adriatic which separates the two nations.[152][153][154] Croatia has not lost against Italy, with most of the fixtures played in qualifications and at tournaments.[155][156] During the Euro 2016 qualifying phase, Croatia and Italy played each other twice, drawing both times.[157] Both matches were marred by crowd trouble due to flares being thrown onto the pitch, which also occurred when the two teams met at the 2012 European Championships. At the 2002 FIFA World Cup, Croatia came from behind to beat Italy 2–1 in another controversial game, after two Italian goals were disallowed.[158] As of July 2018, the two countries have played eight times: Croatia has won three times and drawn five times.[159]

- Their rivalry with France dates back the earliest, with the match played on 15 May 1910, Italy's first official match ending in a 6–2 victory.[160][161] Notable matches in the World Cup and the European Football Championship include the 2006 World Cup Final, when the Italians defeated the French 5–3 in the penalty shoot-out, after a 1–1 draw, and the 2000 European Championship, won by France with an extra-time golden goal by David Trezeguet.[162]

- Their rivalry with Germany is also long-standing, having played against each other five times in the World Cup, notably in the "Game of the Century", the 1970 World Cup semifinal between the two countries that Italy won 4–3 in extra time, with five of the seven goals coming in extra time.[163] Germany has also won three European Championships while Italy has won it once. The two countries have faced each other four times in the European championship, with three draws (one German penalty shoot-out victory) and one Italian victory.[164] Germany had never defeated Italy in a major tournament match until their victory in the Euro 2016 quarterfinals, on penalties (though statistically considered a draw), with all Germany's other wins over Italy being in friendly competitions.[117]

- Their rivalry with Spain, sometimes referred to as the Mediterranean derby,[165] has been contested since 1920, and, although the two nations are not immediate geographical neighbours, their rivalry at international level is enhanced by the strong performances of the representative clubs in UEFA competitions, in which they are among the leading associations and have each enjoyed spells of dominance.[166][167] Since the quarterfinal match between the two countries at Euro 2008, the rivalry has renewed, with its most notable match between the two sides being in the UEFA Euro 2012 Final, which Spain won 4–0.[168][169]

Competitive record

For the all-time record, see Italy national football team all-time record.

Champions Runners-up Third place Fourth place

FIFA World Cup

| FIFA World Cup record | FIFA World Cup qualification record | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Round | Position | Pld | W | D* | L | GF | GA | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | |

| Did not enter | Did not enter | ||||||||||||||

| Champions | 1st | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| Champions | 1st | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 5 | Qualified as defending champions | |||||||

| Group stage | 7th | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | Qualified as defending champions | |||||||

| 10th | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | |||

| Did not qualify | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 5 | |||||||||

| Group stage | 9th | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 2 | ||

| 9th | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 3 | |||

| Runners-up | 2nd | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 3 | ||

| Group stage | 10th | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 0 | ||

| Fourth place | 4th | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 18 | 4 | ||

| Champions | 1st | 7 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 5 | ||

| Round of 16 | 12th | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 6 | Qualified as defending champions | |||||||

| Third place | 3rd | 7 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 2 | Qualified as hosts | |||||||

| Runners-up | 2nd | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 7 | ||

| Quarter-finals | 5th | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 2 | ||

| Round of 16 | 15th | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 3 | ||

| Champions | 1st | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 8 | ||

| Group stage | 26th | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 18 | 7 | ||

| 22nd | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 19 | 9 | |||

| Did not qualify | 12 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 21 | 9 | |||||||||

| To be determined | To be determined | ||||||||||||||

| Total | 4 titles | 18/21 | 83 | 45 | 21 | 17 | 128 | 77 | 109 | 74 | 26 | 9 | 221 | 69 | |

- *Denotes draws include knockout matches decided on penalty shoot-out.

- **Gold background colour indicates that the tournament was won.

- ***Red border colour indicates tournament was held on home soil.

| Italy's World Cup record | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First match | |||||

| Biggest win | |||||

| Biggest defeat | |||||

| Best result | |||||

| Worst result | 26th place at the 2010 World Cup | ||||

UEFA European Championship

| UEFA European Championship record | UEFA European Championship qualifying record | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Round | Position | Pld | W | D* | L | GF | GA | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | |

| Did not enter | Did not enter | ||||||||||||||

| Did not qualify | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 3 | |||||||||

| Champions | 1st | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 21 | 6 | ||

| Did not qualify | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 6 | |||||||||

| 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Fourth place | 4th | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | Qualified as hosts | |||||||

| Did not qualify | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 12 | |||||||||

| Semi finals | 4th | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 4 | ||

| Did not qualify | 8 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 12 | 5 | |||||||||

| Group stage | 10th | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 20 | 6 | ||

| Runners-up | 2nd | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 5 | ||

| Group stage | 9th | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 4 | ||

| Quarter-finals | 8th | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 9 | ||

| Runners-up | 2nd | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 2 | ||

| Quarter-finals | 6th | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 16 | 7 | ||

| Qualified | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 4 | |||||||||

| To be determined | To be determined | ||||||||||||||

| Total | 1 title | 10/16 | 38 | 16 | 16 | 6 | 39 | 27 | 118 | 74 | 30 | 14 | 224 | 76 | |

- *Draws include knockout matches decided by penalty shoot-out.

- **Gold background colour indicates that the tournament was won.

- ***Red border colour indicates tournament was held on home soil.

| Italy's European Championship record | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First match | |||||

| Biggest win | 8 games at 2–0 | ||||

| Biggest defeat | |||||

| Best result | Champions at UEFA Euro 1968 | ||||

| Worst result | 10th place at UEFA Euro 1996 | ||||

UEFA Nations League

| UEFA Nations League record | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Division | Group | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | P/R | Rank |

| A | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 8th | ||

| A | 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 2 | TBD | ||

| Total | 10 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 8th | |||

| Italy's UEFA Nations League record | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First match | |||||

| Biggest win | 2 games at 2–0 | ||||

| Biggest defeat | |||||

| Best result | 8th place in the 2018–19 UEFA Nations League | ||||

| Worst result | |||||

FIFA Confederations Cup

| FIFA Confederations Cup record | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Round | Position | Pld | W | D* | L | GF | GA | |

| No European team participated | |||||||||

| Did not qualify | |||||||||

| Did not enter[170] | |||||||||

| Did not qualify | |||||||||

| Group stage | 5th | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 | ||

| Third place | 3rd | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Did not qualify | |||||||||

| Total | Third place | 2/10 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 13 | 15 | |

- *Draws include knockout matches decided by penalty shoot-out.

| Italy's Confederations Cup record | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First match | |||||

| Biggest win | |||||

| Biggest defeat | |||||

| Best result | Third place at the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup | ||||

| Worst result | 5th place at the 2009 FIFA Confederations Cup | ||||

Honours

- This is a list of honours for the senior Italy national team

Titles

Minor titles:

|

Awards

|

| Competition | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Cup | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| European Championship | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Confederations Cup | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Olympic Games | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Nations League | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 6 | 4 | 4 | 14 |

Coaching staff

Current technical staff:[171]

| Position | Name |

|---|---|

| Head Coach | |

| Assistant Coach(es) | |

| Goalkeeping Coach | |

| Team Manager | |

| Athletic Trainers | |

| Match Analyst | |

| Doctors | |

| Physiotherapists | |

| Osteopath | |

| Nutritionist | |

| Secretary |

During the earliest days of Italian nation football, it was common for a Technical Commission to be appointed. The Commission took the role that a standard coach would currently play. Ever since 1967, the national team has been controlled only by the coach.

For this reason, the coach of the Italy national team is still called Technical Commissioner (Commissario tecnico or CT, the use of this denomination has since then expanded into other team sports in Italy).

Results and fixtures

Win Draw Loss Fixtures

2020

| 4 September 2020 2020–21 UEFA Nations League | Italy | 1–1 | | Florence, Italy |

| 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) |

|

Report |

|

Stadium: Stadio Artemio Franchi Attendance: 0[note 1] Referee: Anastasios Sidiropoulos (Greece) |

| 7 September 2020 2020–21 UEFA Nations League | Netherlands | 0–1 | | Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report |

|

Stadium: Johan Cruyff Arena Attendance: 0[note 1] Referee: Felix Brych (Germany) |

| 7 October 2020 International friendly | Italy | 6–0 | | Florence, Italy |

| 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report | Stadium: Stadio Artemio Franchi Attendance: 0[note 2] Referee: Daniel Siebert (Germany) |

| 11 October 2020 2020–21 UEFA Nations League | Poland | 0–0 | | Gdańsk, Poland |

| 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report | Stadium: Stadion Energa Gdańsk Attendance: 9,200 Referee: José María Sánchez Martínez (Spain) |

| 14 October 2020 2020–21 UEFA Nations League | Italy | 1–1 | | Bergamo, Italy |

| 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) |

|

Report |

|

Stadium: Stadio Atleti Azzurri d'Italia Attendance: 623 Referee: Anthony Taylor (England) |

| 11 November 2020 International friendly | Italy | 4–0 | | Florence, Italy |

| 20:45 CET (UTC+01:00) |

|

Report | Stadium: Stadio Artemio Franchi Attendance: 0[note 2] Referee: Rade Obrenovič (Slovenia) |

| 15 November 2020 2020–21 UEFA Nations League | Italy | 2–0 | | Reggio Emilia, Italy |

| 20:45 CET (UTC+01:00) | Report | Stadium: Stadio Città del Tricolore Attendance: 0[note 2] Referee: Clément Turpin (France) |

| 18 November 2020 2020–21 UEFA Nations League | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0–2 | | Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| 20:45 CET (UTC+01:00) | Report | Stadium: Stadion Grbavica Attendance: 0[note 2] Referee: Artur Soares Dias (Portugal) |

2021

| 25 March 2021 2022 FIFA World Cup qualification | Italy | v | | Parma, Italy |

| 20:45 CET (UTC+01:00) | Report | Stadium: Stadio Ennio Tardini |

| 28 March 2021 2022 FIFA World Cup qualification | Bulgaria | v | | Sofia, Bulgaria |

| 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report | Stadium: Vasil Levski National Stadium |

| 31 March 2021 2022 FIFA World Cup qualification | Lithuania | v | | Vilnius, Lithuania |

| 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report | Stadium: LFF Stadium |

| 11 June 2021 UEFA Euro 2020 Group A | Turkey | v | | Rome, Italy |

| 21:00 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report | Stadium: Stadio Olimpico |

| 16 June 2021 UEFA Euro 2020 Group A | Italy | v | | Rome, Italy |

| 21:00 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report | Stadium: Stadio Olimpico |

| 20 June 2021 UEFA Euro 2020 Group A | Italy | v | | Rome, Italy |

| 18:00 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report | Stadium: Stadio Olimpico |

| 2 September 2021 2022 FIFA World Cup qualification | Italy | v | | Italy |

| 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report |

| 5 September 2021 2022 FIFA World Cup qualification | Switzerland | v | | Switzerland |

| 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report |

| 8 September 2021 2022 FIFA World Cup qualification | Italy | v | | Italy |

| 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report |

| 6 October 2021 2020–21 UEFA Nations League SF | Italy | v | | Milan, Italy |

| 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Report | Stadium: San Siro |

| 10 October 2021 2020–21 UEFA Nations League 3rd/F | Italy | v | | Milan or Turin, Italy |

| 15:00 or 20:45 CEST (UTC+02:00) | Stadium: San Siro or Juventus Stadium |

| 12 November 2021 2022 FIFA World Cup qualification | Italy | v | | Italy |

| 20:45 CET (UTC+01:00) | Report |

| 15 November 2021 2022 FIFA World Cup qualification | Northern Ireland | v | | Northern Ireland |

| 20:45 CET (UTC+01:00) | Report |

Players

Current squad

The following players were called up for the friendly match against Estonia on 11 November 2020 and the 2020–21 UEFA Nations League matches against Poland on 15 November 2020 and Bosnia and Herzegovina on 18 November 2020.[174]

Caps and goals updated as of 18 November 2020, after the match against Bosnia and Herzegovina.

| No. | Pos. | Player | Date of birth (age) | Caps | Goals | Club |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GK | Salvatore Sirigu | 12 January 1987 | 26 | 0 | |

| 12 | GK | Alex Meret | 22 March 1997 | 1 | 0 | |

| 21 | GK | Gianluigi Donnarumma | 25 February 1999 | 22 | 0 | |

| GK | Alessio Cragno | 28 June 1994 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 2 | DF | Danilo D'Ambrosio | 9 September 1988 | 6 | 0 | |

| 3 | DF | Emerson Palmieri | 3 August 1994 | 12 | 0 | |

| 6 | DF | Alessio Romagnoli | 12 January 1995 | 12 | 2 | |

| 13 | DF | Davide Calabria | 6 December 1996 | 2 | 0 | |

| 15 | DF | Francesco Acerbi | 10 February 1988 | 11 | 1 | |

| 16 | DF | Alessandro Florenzi | 11 March 1991 | 40 | 2 | |

| 19 | DF | Alessandro Bastoni | 13 April 1999 | 3 | 0 | |

| 23 | DF | Giovanni Di Lorenzo | 4 August 1993 | 5 | 0 | |

| DF | Luca Pellegrini | 7 March 1999 | 1 | 0 | ||

| DF | Gian Marco Ferrari | 15 February 1992 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | MF | Sandro Tonali | 8 May 2000 | 4 | 0 | |

| 5 | MF | Manuel Locatelli | 8 January 1998 | 6 | 0 | |

| 8 | MF | Jorginho | 20 December 1991 | 27 | 5 | |

| 14 | MF | Roberto Soriano | 8 February 1991 | 9 | 0 | |

| 17 | MF | Matteo Pessina | 21 April 1997 | 1 | 0 | |

| 18 | MF | Nicolò Barella | 7 February 1997 | 18 | 4 | |

| 7 | FW | Kevin Lasagna | 10 August 1992 | 7 | 0 | |

| 9 | FW | Andrea Belotti | 20 December 1993 | 31 | 10 | |

| 10 | FW | Lorenzo Insigne | 4 June 1991 | 38 | 7 | |

| 11 | FW | Domenico Berardi | 1 August 1994 | 9 | 3 | |

| 20 | FW | Federico Bernardeschi | 16 February 1994 | 27 | 5 | |

| 22 | FW | Riccardo Orsolini | 24 January 1997 | 2 | 2 | |

| FW | Stephan El Shaarawy | 27 October 1992 | 28 | 6 | ||

| FW | Federico Chiesa | 25 October 1997 | 21 | 1 | ||

| FW | Stefano Okaka | 9 August 1989 | 5 | 1 | ||

Recent call-ups

The following footballers have been selected in the past 12 months and are still eligible to represent.

| Pos. | Player | Date of birth (age) | Caps | Goals | Club | Latest call-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GK | Marco Silvestri | 2 March 1991 | 0 | 0 | v. | |

| DF | Cristiano Biraghi | 1 September 1992 | 9 | 1 | v. | |

| DF | Leonardo Bonucci INJ | 1 May 1987 | 99 | 7 | v. | |

| DF | Domenico Criscito INJ | 30 December 1986 | 26 | 0 | v. | |

| DF | Angelo Ogbonna INJ | 23 May 1988 | 13 | 0 | v. | |

| DF | Leonardo Spinazzola | 25 March 1993 | 10 | 0 | v. | |

| DF | Gianluca Mancini | 17 April 1996 | 4 | 0 | v. | |

| DF | Giorgio Chiellini (Captain) | 14 August 1984 | 105 | 8 | v. | |

| DF | Manuel Lazzari INJ | 29 November 1993 | 2 | 0 | v. | |

| DF | Mattia Caldara | 5 May 1994 | 2 | 0 | v. | |

| MF | Gaetano Castrovilli | 17 February 1997 | 1 | 0 | v. | |

| MF | Lorenzo Pellegrini | 19 June 1996 | 15 | 2 | v. | |

| MF | Bryan Cristante | 3 March 1995 | 9 | 1 | v. | |

| MF | Roberto Gagliardini | 7 April 1994 | 7 | 0 | v. | |

| MF | Mattia Zaccagni INJ | 16 June 1995 | 0 | 0 | v. | |

| MF | Marco Verratti | 5 November 1992 | 38 | 3 | v. | |

| MF | Stefano Sensi | 5 August 1995 | 6 | 2 | v. | |

| MF | Giacomo Bonaventura | 22 August 1989 | 15 | 0 | v. | |

| MF | Nicolò Zaniolo | 2 July 1999 | 7 | 2 | v. | |

| FW | Ciro Immobile | 20 February 1990 | 42 | 10 | v. | |

| FW | Moise Kean INJ | 28 February 2000 | 8 | 2 | v. | |

| FW | Vincenzo Grifo | 7 April 1993 | 4 | 2 | v. | |

| FW | Francesco Caputo INJ | 6 August 1987 | 2 | 1 | v. | |

| FW | Pietro Pellegri INJ | 17 March 2001 | 1 | 0 | v. | |

INJ Withdrew due to injury | ||||||

Previous squads

Records

Most capped players

.jpg.webp)

As of 14 October 2020, the players with the most appearances for Italy are:[175]

| # | Player | Period | Caps | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gianluigi Buffon | 1997–2018 | 176 | 0 |

| 2 | Fabio Cannavaro | 1997–2010 | 136 | 2 |

| 3 | Paolo Maldini | 1988–2002 | 126 | 7 |

| 4 | Daniele De Rossi | 2004–2017 | 117 | 21 |

| 5 | Andrea Pirlo | 2002–2015 | 116 | 13 |

| 6 | Dino Zoff | 1968–1983 | 112 | 0 |

| 7 | Giorgio Chiellini | 2004– | 105 | 8 |

| 8 | Leonardo Bonucci | 2010– | 99 | 7 |

| 9 | Gianluca Zambrotta | 1999–2010 | 98 | 2 |

| 10 | Giacinto Facchetti | 1963–1977 | 94 | 3 |

Players in bold are still active in the national football team.

Top goalscorers

.JPG.webp)

As of 14 October 2020, the players with the most goals for Italy are:[176]

| # | Player | Period | Goals | Caps | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luigi Riva (list) | 1965–1974 | 35 | 42 | 0.83 |

| 2 | Giuseppe Meazza | 1930–1939 | 33 | 53 | 0.62 |

| 3 | Silvio Piola | 1935–1952 | 30 | 34 | 0.88 |

| 4 | Roberto Baggio | 1988–2004 | 27 | 56 | 0.48 |

| Alessandro Del Piero | 1995–2008 | 91 | 0.3 | ||

| 6 | Adolfo Baloncieri | 1920–1930 | 25 | 47 | 0.53 |

| Filippo Inzaghi | 1997–2007 | 57 | 0.44 | ||

| Alessandro Altobelli | 1980–1988 | 61 | 0.41 | ||

| 9 | Christian Vieri | 1997–2005 | 23 | 49 | 0.47 |

| Francesco Graziani | 1975–1983 | 64 | 0.36 |

Players in bold are still active in the national football team.

Captains

List of captaincy periods of the various captains throughout the years.[177]

- 1910 Francesco Calì

- 1911–1914 Giuseppe Milano

- 1914–1915 Virgilio Fossati

- 1920–1925 Renzo De Vecchi

- 1925–1927 Luigi Cevenini

- 1927–1930 Adolfo Baloncieri

- 1931–1934 Umberto Caligaris

- 1934 Gianpiero Combi

- 1935–1936 Luigi Allemandi

- 1937–1939 Giuseppe Meazza

- 1940–1947 Silvio Piola

- 1947–1949 Valentino Mazzola

- 1949–1950 Riccardo Carapellese

- 1951–1952 Carlo Annovazzi

- 1952–1960 Giampiero Boniperti

- 1961–1962 Lorenzo Buffon

- 1962–1963 Cesare Maldini

- 1963–1966 Sandro Salvadore

- 1966–1977 Giacinto Facchetti

- 1977–1983 Dino Zoff

- 1983–1985 Marco Tardelli

- 1985–1986 Gaetano Scirea

- 1986–1987 Antonio Cabrini

- 1988–1991 Giuseppe Bergomi

- 1991–1994 Franco Baresi

- 1994–2002 Paolo Maldini

- 2002–2010 Fabio Cannavaro[nb 2]

- 2010–2018 Gianluigi Buffon[nb 3]

- 2018–present Giorgio Chiellini

Hat-tricks

Head to head records

For head to head records against other countries, see Italy national football team head to head.

As of 18 November 2019, the complete official match record of the Italian national team comprises 823 matches: 437 wins, 224 draws and 162 losses.[187] During these matches, the team scored 1,433 times and conceded 818 goals. Italy's highest winning margin is nine goals, which has been achieved against the United States in 1948 (9–0). Their longest winning streak is 11 wins,[188] and their unbeaten record is 30 consecutive official matches.[189]

See also

- Italy women's national football team

- Italy national under-21 football team

- Italy national under-20 football team

- Italy national under-19 football team

- Italy national under-17 football team

- Italy national beach soccer team

- Italy national futsal team

- Serie A

- Football in Italy

- Sport in Italy

- List of cultural icons of Italy

Notes

- Monaco is a Monégasque club playing in the French football league system.

- This edition of the tournament was interrupted due to the annexation of Austria to Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938.

- During UEFA Euro 2008, Alessandro Del Piero was named the Italy national team acting captain, as Cannavaro was injured and unable to take part in the competition, however Gianluigi Buffon was often played as captain as Del Piero was frequently deployed as a substitute.[178][179][180]

- Gianluigi Buffon served as second acting captain in UEFA Euro 2008 after Alessandro Del Piero was named the team's acting captain, as Cannavaro was injured and unable to take part in the competition, however Del Piero was frequently deployed as a substitute.[180] Although Buffon was officially named Italy's new captain in 2010,[181] following Fabio Cannavaro's retirement subsequent to the 2010 FIFA World Cup, Andrea Pirlo was named the Italy national team's acting captain after the tournament (while Daniele De Rossi was named the team's second acting captain),[181][182][183] as Buffon was ruled out until the end of the year due to injury, and only made his first appearance as Italy's official captain on 9 February 2011, in a 1–1 friendly away draw against Germany.[181][184][185][186]

- Due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe, all matches scheduled for September 2020 were played behind closed doors.[172][173]

- Due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe, the match was played behind closed doors.

References

- "The FIFA/Coca-Cola World Ranking". FIFA. 10 December 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- "Album della stagione" (in Italian). MagliaRossonera.it. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- "Pietro Lana" (in Italian). MagliaRossonera.it. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- "FIGC". Figc.it. Archived from the original on 23 April 2007. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- "Italia-Francia IL CALCIO" (PDF) (in Italian). repubblica.it. 17 October 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2006. Retrieved 24 October 2006.

- "1st International Cup". www.rsssf.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- "3rd International Cup". www.rsssf.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- "Football at the 1936 Berlin Summer Games". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on 11 October 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- "Giuseppe Meazza La favola di Peppin il folbèr" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "The inimitable Giuseppe Meazza". FIFA.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- Martin, Simon (1 April 2014): "World Cup: 25 stunning moments … No8: Mussolini's blackshirts' 1938 win". Archived 24 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine theguardian.com. Läst 22 April 2016.

- Lisi (2007), p. 47

- "1966 World Cup: Football comes home". cbc.ca. 26 November 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- "1966: Portugal - Korea DPR". yahoo.com. 16 May 2006. Archived from the original on 16 May 2006.

- Sam Sheringham (12 May 2012). "Euro 1968: Alan Mullery's moment of madness". bbc.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- Matt Wagg (28 June 2012). "Euro 2012: five classic tournament matches between Germany and Italy including the 'Game of the Century'". telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "Classic Football: Dino Zoff – I was there". FIFA Official Site. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "1980 at a glance". uefa.com. 1 July 2011. Archived from the original on 4 November 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- Dan Warren (25 July 2006). "The worst scandal of them all". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- Duarte, Fernando (30 May 2014). "Brazil lost that Italy game in 1982 but won a place in history – Falcão". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- Wilson, Jonathan (25 July 2012). "Italy 3–2 Brazil, 1982: the day naivety, not football itself, died". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- Lewis, Tim (11 July 2014). "1982: Why Brazil V Italy Was One Of Football's Greatest Ever Matches". Esquire. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "Sparkling Italy spring ultimate upset". Glasgow Herald. 12 July 1982. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- "Marco Tardelli" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "Paolo Rossi: La solitudine del centravanti" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "World Cup Hall of Fame: Dino Zoff". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 12 September 2005.

- Almanacco Illustrato del Calcio 1984 (in Italian). Panini Group. 1983. p. 393.

- Gianni Brera (23 May 1984). "Italia-Germania Che noia mundial!". la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 37. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Mario Sconcerti (26 September 1985). "L' Italia s' è persa". la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 27. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Gianni Brera (17 November 1985). "Ma per l' Italia altri cento di questi giorni..." la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 25. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Fabrizio Bocca (6 February 1986). "E ora Beckenbauer pensa alla grande". la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 18. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Mario Sconcerti (18 June 1986). "Povero Bearzot". la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 1. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- "Alla ricerca dell' Italia perduta". la Repubblica (in Italian). 3 August 1986. p. 26. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- "Quante novità nell'anno di Vicini". la Repubblica (in Italian). 12 June 1987. p. 45. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Gianni Mura (15 November 1987). "Viva Vialli". la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 22. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Gianni Brera (21 February 1988). "Abbracciati a Vialli". la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 21. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Gianni Brera (25 June 1988). "Questa URSS non è perfetta". la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 23. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Maradona, Diego (2004). El Diego, pg. 165.

- "Italy oust Brazil to take top spot". FIFA.com. 14 February 2007. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- "Match Report – 1994 FIFA World Cup USA (TM): Nigeria – Italy". FIFA.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- "Match Report – 1994 FIFA World Cup USA (TM): Italy – Spain". FIFA.com. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- "Match Report – 1994 FIFA World Cup USA (TM): Bulgaria – Italy". FIFA.com. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- "USA 94". news.bbc.co.uk. 17 April 2002. Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "Divine by moniker, divine by magic". fifa.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "ci resta un filo di Baggio" (in Italian). Il Corriere della Sera. 15 July 1994. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "Has so much ever hung on a hamstring? – Roberto Baggio, Italy's Footballing Hero". The Independent. London. 16 July 1994. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "e Baggio sbaglia il tiro della sua vita" (in Italian). Il Corriere della Sera. 18 July 1994. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "Da Baggio a McEnroe e Schumi Come si sbaglia un punto decisivo" (in Italian). Il Corriere della Sera. 31 October 2006. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "Italy pay penalty for Germany stalemate". UEFA.com. 6 October 2003. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- "World Cup 2018: Italy and the nightmare of their play-off against Sweden". bbc.com. 10 November 2017. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "10 Leggende Mondiali" [10 World Cup Legends] (in Italian). Eurosport. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "France 2 Italy 1". BBC Sport. 2 July 2000. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- Ivan Speck (4 July 2000). "Zoff resigned after attack from Berlusconi". espnfc.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "Angry Italy blame 'conspiracy'". Soccernet. 19 June 2002. Archived from the original on 23 November 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2006.

- Ghosh, Bobby (24 June 2002). "Lay Off the Refs". Time. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- "Fifa investigates Moreno". BBC News. 13 September 2002. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "Blatter condemns officials". BBC News. 20 June 2002. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "Flachi, Toni and Blasi here's Lippi's news". repubblica.it (in Italian). 14 August 2004. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- "Bad debut for Lippi Italy knocked out in Iceland". repubblica.it (in Italian). 18 August 2004. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- "Bitter Slovenia for Italy who loses match and top". repubblica.it (in Italian). 9 October 2004. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- Enrico Currò (14 October 2004). "Qualificazioni mondiali". la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 50. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- "People's Daily Online – Scandal threatening to bury Italy's Cup dream". English.people.com.cn. 23 May 2006. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Buckley, Kevin (21 May 2006). "Lippi the latest to be sucked into crisis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 May 2006. Retrieved 27 June 2006.

- Dampf, Andrew (12 June 2006). "Pirlo Leads Italy Past Ghana at World Cup". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- "Italia-Usa: la guerra che non si voleva Pari con 3 espulsi. Qualificazione rinviata". repubblica.it (in Italian). La Repubblica. 17 June 2006. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- "Italy 1–0 Australia". BBC Sport. 26 June 2006. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "Lippi dedicates win to Pessotto". BBC. 30 June 2006. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2006.

- "Germany 0–2 Italy (aet)". BBC Sport. 4 July 2006. Archived from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "And Materazzi's exact words to Zidane were..., Football, guardian.co.uk". Guardian. UK. 18 August 2007. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- Stevenson, Jonathan (9 July 2006). "Italy 1–1 France (aet)". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "Azzurri prominent in All Star Team". FIFA.com. 7 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- "Buffon collects Lev Yashin Award". FIFA.com. 10 July 2006. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2006.

- "Italy squad given heroes' welcome". BBC Sport. 10 July 2006. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "Italian joy at World Cup victory". BBC Sport. 10 July 2006. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "Nazionale, scelto l'erede di Lippi Donadoni è il nuovo ct degli azzurri" (in Italian). La Repubblica Sport. 13 July 2006. Archived from the original on 16 March 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- "Every major nation's lowest FIFA rank since records began". squawka.com. 10 September 2018. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "Italy 1-1 Romania". 13 June 2008 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- "Lippi returns to manage Italy". TribalFootball.com. 27 June 2008. Archived from the original on 18 November 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Paul Wilson (24 June 2010). "World Cup 2010: Italy exit as Slovakia turf out reigning champions". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- "Italy side looks to slay ghost of World Cup 2010". thelocal.it. 3 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- Duggan, Keith (25 June 2010). "Italy out of Africa and Lippi out of excuses". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "Fiorentina manager Prandelli accepts Italy job". BBC Sport. 30 May 2010. Archived from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- Jackson, Jamie (10 August 2010). "Italy's new dawn fails to rise in dismal defeat by Ivory Coast". The Guardina. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- "Fan Flares Interrupt Italy-Serbia Match". 13 October 2010 – via www.wsj.com.

- "Uefa hands Italy 3–0 win after Serbia violence in Genoa". BBC Sport. 29 October 2010. Archived from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- "Italy crash to USA defeat". Sky Sports. 29 February 2012. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- McNulty, Phil (24 June 2012). "England – Italy 0–0". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2018.