Bohr model

In atomic physics, the Bohr model or Rutherford–Bohr model, presented by Niels Bohr and Ernest Rutherford in 1913, is a system consisting of a small, dense nucleus surrounded by orbiting electrons—similar to the structure of the Solar System, but with attraction provided by electrostatic forces in place of gravity. After the cubical model (1902), the plum pudding model (1904), the Saturnian model (1904), and the Rutherford model (1911) came the Rutherford–Bohr model or just Bohr model for short (1913). The improvement over the 1911 Rutherford model mainly concerned the new quantum physical interpretation.

The model's key success lay in explaining the Rydberg formula for the spectral emission lines of atomic hydrogen. While the Rydberg formula had been known experimentally, it did not gain a theoretical underpinning until the Bohr model was introduced. Not only did the Bohr model explain the reasons for the structure of the Rydberg formula, it also provided a justification for the fundamental physical constants that make up the formula's empirical results.

The Bohr model is a relatively primitive model of the hydrogen atom, compared to the valence shell atom model. As a theory, it can be derived as a first-order approximation of the hydrogen atom using the broader and much more accurate quantum mechanics and thus may be considered to be an obsolete scientific theory. However, because of its simplicity, and its correct results for selected systems (see below for application), the Bohr model is still commonly taught to introduce students to quantum mechanics or energy level diagrams before moving on to the more accurate, but more complex, valence shell atom. A related model was originally proposed by Arthur Erich Haas in 1910 but was rejected. The quantum theory of the period between Planck's discovery of the quantum (1900) and the advent of a mature quantum mechanics (1925) is often referred to as the old quantum theory.

Origin

In the early 20th century, experiments by Ernest Rutherford established that atoms consisted of a diffuse cloud of negatively charged electrons surrounding a small, dense, positively charged nucleus.[2] Given this experimental data, Rutherford naturally considered a planetary model of the atom, the Rutherford model of 1911. This had electrons orbiting a solar nucleus, but involved a technical difficulty: the laws of classical mechanics (i.e. the Larmor formula) predict that the electron will release electromagnetic radiation while orbiting a nucleus. Because the electron would lose energy, it would rapidly spiral inwards, collapsing into the nucleus on a timescale of around 16 picoseconds.[3] This atom model is disastrous because it predicts that all atoms are unstable.[4] Also, as the electron spirals inward, the emission would rapidly increase in frequency as the orbit got smaller and faster. This would cause a continuous stream of electromagnetic radiation. However, late 19th-century experiments with electric discharges had shown that atoms will only emit light (that is, electromagnetic radiation) at certain discrete frequencies.

To overcome the problems of Rutherford's atom, in 1913 Niels Bohr put forth three postulates that sum up most of his model:

- The electron is able to revolve in certain stable orbits around the nucleus without radiating any energy, contrary to what classical electromagnetism suggests. These stable orbits are called stationary orbits and are attained at certain discrete distances from the nucleus. The electron cannot have any other orbit in between the discrete ones.

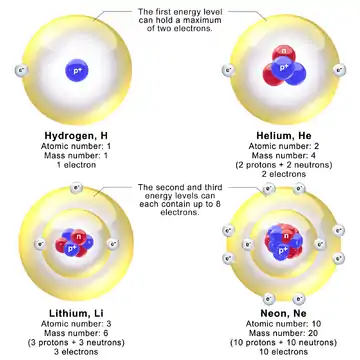

- The stationary orbits are attained at distances for which the angular momentum of the revolving electron is an integer multiple of the reduced Planck constant: , where n = 1, 2, 3, ... is called the principal quantum number, and ħ = h/2π. The lowest value of n is 1; this gives the smallest possible orbital radius of 0.0529 nm known as the Bohr radius. Once an electron is in this lowest orbit, it can get no closer to the proton. Starting from the angular momentum quantum rule, Bohr[2] was able to calculate the energies of the allowed orbits of the hydrogen atom and other hydrogen-like atoms and ions. These orbits are associated with definite energies and are also called energy shells or energy levels. In these orbits, the electron's acceleration does not result in radiation and energy loss. The Bohr model of an atom was based upon Planck's quantum theory of radiation.

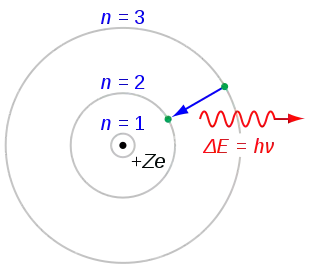

- Electrons can only gain and lose energy by jumping from one allowed orbit to another, absorbing or emitting electromagnetic radiation with a frequency ν determined by the energy difference of the levels according to the Planck relation: , where h is Planck's constant.

Other points are:

- Like Einstein's theory of the photoelectric effect, Bohr's formula assumes that during a quantum jump a discrete amount of energy is radiated. However, unlike Einstein, Bohr stuck to the classical Maxwell theory of the electromagnetic field. Quantization of the electromagnetic field was explained by the discreteness of the atomic energy levels; Bohr did not believe in the existence of photons.[5][6]

- According to the Maxwell theory the frequency ν of classical radiation is equal to the rotation frequency νrot of the electron in its orbit, with harmonics at integer multiples of this frequency. This result is obtained from the Bohr model for jumps between energy levels En and En−k when k is much smaller than n. These jumps reproduce the frequency of the k-th harmonic of orbit n. For sufficiently large values of n (so-called Rydberg states), the two orbits involved in the emission process have nearly the same rotation frequency, so that the classical orbital frequency is not ambiguous. But for small n (or large k), the radiation frequency has no unambiguous classical interpretation. This marks the birth of the correspondence principle, requiring quantum theory to agree with the classical theory only in the limit of large quantum numbers.

- The Bohr–Kramers–Slater theory (BKS theory) is a failed attempt to extend the Bohr model, which violates the conservation of energy and momentum in quantum jumps, with the conservation laws only holding on average.

Bohr's condition, that the angular momentum is an integer multiple of ħ was later reinterpreted in 1924 by de Broglie as a standing wave condition: the electron is described by a wave and a whole number of wavelengths must fit along the circumference of the electron's orbit:

According to de Broglie hypothesis, matter particles such as the electron behaves as waves. So, de Broglie wavelength of electron is:

- .

which implies that,

or

where is the angular momentum of the orbiting electron.

which is the Bohr's second postulate.

Bohr described angular momentum of the electron orbit as 1/2h while de Broglie's wavelength of λ = h/p described h divided by the electron momentum. In 1913, however, Bohr justified his rule by appealing to the correspondence principle, without providing any sort of wave interpretation. In 1913, the wave behavior of matter particles such as the electron was not suspected.

In 1925, a new kind of mechanics was proposed, quantum mechanics, in which Bohr's model of electrons traveling in quantized orbits was extended into a more accurate model of electron motion. The new theory was proposed by Werner Heisenberg. Another form of the same theory, wave mechanics, was discovered by the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger independently, and by different reasoning. Schrödinger employed de Broglie's matter waves, but sought wave solutions of a three-dimensional wave equation describing electrons that were constrained to move about the nucleus of a hydrogen-like atom, by being trapped by the potential of the positive nuclear charge.

Electron energy levels

The Bohr model gives almost exact results only for a system where two charged points orbit each other at speeds much less than that of light. This not only involves one-electron systems such as the hydrogen atom, singly ionized helium, and doubly ionized lithium, but it includes positronium and Rydberg states of any atom where one electron is far away from everything else. It can be used for K-line X-ray transition calculations if other assumptions are added (see Moseley's law below). In high energy physics, it can be used to calculate the masses of heavy quark mesons.

Calculation of the orbits requires two assumptions.

- Classical mechanics

- The electron is held in a circular orbit by electrostatic attraction. The centripetal force is equal to the Coulomb force.

- where me is the electron's mass, e is the charge of the electron, ke is the Coulomb constant and Z is the atom's atomic number. It is assumed here that the mass of the nucleus is much larger than the electron mass (which is a good assumption). This equation determines the electron's speed at any radius:

- It also determines the electron's total energy at any radius:

- The total energy is negative and inversely proportional to r. This means that it takes energy to pull the orbiting electron away from the proton. For infinite values of r, the energy is zero, corresponding to a motionless electron infinitely far from the proton. The total energy is half the potential energy, the difference being the kinetic energy of the electron. This is also true for noncircular orbits by the virial theorem.

- A quantum rule

- The angular momentum L = mevr is an integer multiple of ħ:

Derivation

If an electron in an atom is moving on an orbit with period T, classically the electromagnetic radiation will repeat itself every orbital period. If the coupling to the electromagnetic field is weak, so that the orbit doesn't decay very much in one cycle, the radiation will be emitted in a pattern which repeats every period, so that the Fourier transform will have frequencies which are only multiples of 1/T. This is the classical radiation law: the frequencies emitted are integer multiples of 1/T.

In quantum mechanics, this emission must be in quanta of light, of frequencies consisting of integer multiples of 1/T, so that classical mechanics is an approximate description at large quantum numbers. This means that the energy level corresponding to a classical orbit of period 1/T must have nearby energy levels which differ in energy by h/T, and they should be equally spaced near that level,

Bohr worried whether the energy spacing 1/T should be best calculated with the period of the energy state , or , or some average—in hindsight, this model is only the leading semiclassical approximation.

Bohr considered circular orbits. Classically, these orbits must decay to smaller circles when photons are emitted. The level spacing between circular orbits can be calculated with the correspondence formula. For a Hydrogen atom, the classical orbits have a period T determined by Kepler's third law to scale as r3/2. The energy scales as 1/r, so the level spacing formula amounts to

It is possible to determine the energy levels by recursively stepping down orbit by orbit, but there is a shortcut.

The angular momentum L of the circular orbit scales as √r. The energy in terms of the angular momentum is then

- .

Assuming, with Bohr, that quantized values of L are equally spaced, the spacing between neighboring energies is

This is as desired for equally spaced angular momenta. If one kept track of the constants, the spacing would be ħ, so the angular momentum should be an integer multiple of ħ,

This is how Bohr arrived at his model.

- Substituting the expression for the velocity gives an equation for r in terms of n:

- so that the allowed orbit radius at any n is:

- The smallest possible value of r in the hydrogen atom (Z = 1) is called the Bohr radius and is equal to:

- The energy of the n-th level for any atom is determined by the radius and quantum number:

An electron in the lowest energy level of hydrogen (n = 1) therefore has about 13.6 eV less energy than a motionless electron infinitely far from the nucleus. The next energy level (n = 2) is −3.4 eV. The third (n = 3) is −1.51 eV, and so on. For larger values of n, these are also the binding energies of a highly excited atom with one electron in a large circular orbit around the rest of the atom. The hydrogen formula also coincides with the Wallis product.[7]

The combination of natural constants in the energy formula is called the Rydberg energy (RE):

This expression is clarified by interpreting it in combinations that form more natural units:

- is the rest mass energy of the electron (511 keV)

- is the fine structure constant

Since this derivation is with the assumption that the nucleus is orbited by one electron, we can generalize this result by letting the nucleus have a charge q = Ze, where Z is the atomic number. This will now give us energy levels for hydrogenic (hydrogen-like) atoms, which can serve as a rough order-of-magnitude approximation of the actual energy levels. So for nuclei with Z protons, the energy levels are (to a rough approximation):

The actual energy levels cannot be solved analytically for more than one electron (see n-body problem) because the electrons are not only affected by the nucleus but also interact with each other via the Coulomb Force.

When Z = 1/α (Z ≈ 137), the motion becomes highly relativistic, and Z2 cancels the α2 in R; the orbit energy begins to be comparable to rest energy. Sufficiently large nuclei, if they were stable, would reduce their charge by creating a bound electron from the vacuum, ejecting the positron to infinity. This is the theoretical phenomenon of electromagnetic charge screening which predicts a maximum nuclear charge. Emission of such positrons has been observed in the collisions of heavy ions to create temporary super-heavy nuclei.[8]

The Bohr formula properly uses the reduced mass of electron and proton in all situations, instead of the mass of the electron,

However, these numbers are very nearly the same, due to the much larger mass of the proton, about 1836.1 times the mass of the electron, so that the reduced mass in the system is the mass of the electron multiplied by the constant 1836.1/(1+1836.1) = 0.99946. This fact was historically important in convincing Rutherford of the importance of Bohr's model, for it explained the fact that the frequencies of lines in the spectra for singly ionized helium do not differ from those of hydrogen by a factor of exactly 4, but rather by 4 times the ratio of the reduced mass for the hydrogen vs. the helium systems, which was much closer to the experimental ratio than exactly 4.

For positronium, the formula uses the reduced mass also, but in this case, it is exactly the electron mass divided by 2. For any value of the radius, the electron and the positron are each moving at half the speed around their common center of mass, and each has only one fourth the kinetic energy. The total kinetic energy is half what it would be for a single electron moving around a heavy nucleus.

- (positronium)

Rydberg formula

The Rydberg formula, which was known empirically before Bohr's formula, is seen in Bohr's theory as describing the energies of transitions or quantum jumps between orbital energy levels. Bohr's formula gives the numerical value of the already-known and measured the Rydberg constant, but in terms of more fundamental constants of nature, including the electron's charge and the Planck constant.

When the electron gets moved from its original energy level to a higher one, it then jumps back each level until it comes to the original position, which results in a photon being emitted. Using the derived formula for the different energy levels of hydrogen one may determine the wavelengths of light that a hydrogen atom can emit.

The energy of a photon emitted by a hydrogen atom is given by the difference of two hydrogen energy levels:

where nf is the final energy level, and ni is the initial energy level.

Since the energy of a photon is

the wavelength of the photon given off is given by

This is known as the Rydberg formula, and the Rydberg constant R is RE/hc, or RE/2π in natural units. This formula was known in the nineteenth century to scientists studying spectroscopy, but there was no theoretical explanation for this form or a theoretical prediction for the value of R, until Bohr. In fact, Bohr's derivation of the Rydberg constant, as well as the concomitant agreement of Bohr's formula with experimentally observed spectral lines of the Lyman (nf =1), Balmer (nf =2), and Paschen (nf =3) series, and successful theoretical prediction of other lines not yet observed, was one reason that his model was immediately accepted.

To apply to atoms with more than one electron, the Rydberg formula can be modified by replacing Z with Z − b or n with n − b where b is constant representing a screening effect due to the inner-shell and other electrons (see Electron shell and the later discussion of the "Shell Model of the Atom" below). This was established empirically before Bohr presented his model.

Shell model (heavier atoms)

Bohr extended the model of hydrogen to give an approximate model for heavier atoms. This gave a physical picture that reproduced many known atomic properties for the first time.

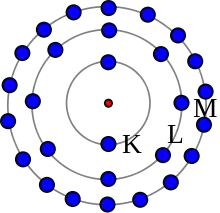

Heavier atoms have more protons in the nucleus, and more electrons to cancel the charge. Bohr's idea was that each discrete orbit could only hold a certain number of electrons. After that orbit is full, the next level would have to be used. This gives the atom a shell structure, in which each shell corresponds to a Bohr orbit.

This model is even more approximate than the model of hydrogen, because it treats the electrons in each shell as non-interacting. But the repulsions of electrons are taken into account somewhat by the phenomenon of screening. The electrons in outer orbits do not only orbit the nucleus, but they also move around the inner electrons, so the effective charge Z that they feel is reduced by the number of the electrons in the inner orbit.

For example, the lithium atom has two electrons in the lowest 1s orbit, and these orbit at Z = 2. Each one sees the nuclear charge of Z = 3 minus the screening effect of the other, which crudely reduces the nuclear charge by 1 unit. This means that the innermost electrons orbit at approximately 1/2 the Bohr radius. The outermost electron in lithium orbits at roughly the Bohr radius, since the two inner electrons reduce the nuclear charge by 2. This outer electron should be at nearly one Bohr radius from the nucleus. Because the electrons strongly repel each other, the effective charge description is very approximate; the effective charge Z doesn't usually come out to be an integer. But Moseley's law experimentally probes the innermost pair of electrons, and shows that they do see a nuclear charge of approximately Z − 1, while the outermost electron in an atom or ion with only one electron in the outermost shell orbits a core with effective charge Z − k where k is the total number of electrons in the inner shells.

The shell model was able to qualitatively explain many of the mysterious properties of atoms which became codified in the late 19th century in the periodic table of the elements. One property was the size of atoms, which could be determined approximately by measuring the viscosity of gases and density of pure crystalline solids. Atoms tend to get smaller toward the right in the periodic table, and become much larger at the next line of the table. Atoms to the right of the table tend to gain electrons, while atoms to the left tend to lose them. Every element on the last column of the table is chemically inert (noble gas).

In the shell model, this phenomenon is explained by shell-filling. Successive atoms become smaller because they are filling orbits of the same size, until the orbit is full, at which point the next atom in the table has a loosely bound outer electron, causing it to expand. The first Bohr orbit is filled when it has two electrons, which explains why helium is inert. The second orbit allows eight electrons, and when it is full the atom is neon, again inert. The third orbital contains eight again, except that in the more correct Sommerfeld treatment (reproduced in modern quantum mechanics) there are extra "d" electrons. The third orbit may hold an extra 10 d electrons, but these positions are not filled until a few more orbitals from the next level are filled (filling the n=3 d orbitals produces the 10 transition elements). The irregular filling pattern is an effect of interactions between electrons, which are not taken into account in either the Bohr or Sommerfeld models and which are difficult to calculate even in the modern treatment.

Moseley's law and calculation (K-alpha X-ray emission lines)

Niels Bohr said in 1962, "You see actually the Rutherford work was not taken seriously. We cannot understand today, but it was not taken seriously at all. There was no mention of it any place. The great change came from Moseley."[9]

In 1913, Henry Moseley found an empirical relationship between the strongest X-ray line emitted by atoms under electron bombardment (then known as the K-alpha line), and their atomic number Z. Moseley's empiric formula was found to be derivable from Rydberg and Bohr's formula (Moseley actually mentions only Ernest Rutherford and Antonius Van den Broek in terms of models). The two additional assumptions that [1] this X-ray line came from a transition between energy levels with quantum numbers 1 and 2, and [2], that the atomic number Z when used in the formula for atoms heavier than hydrogen, should be diminished by 1, to (Z − 1)2.

Moseley wrote to Bohr, puzzled about his results, but Bohr was not able to help. At that time, he thought that the postulated innermost "K" shell of electrons should have at least four electrons, not the two which would have neatly explained the result. So Moseley published his results without a theoretical explanation.

Later, people realized that the effect was caused by charge screening, with an inner shell containing only 2 electrons. In the experiment, one of the innermost electrons in the atom is knocked out, leaving a vacancy in the lowest Bohr orbit, which contains a single remaining electron. This vacancy is then filled by an electron from the next orbit, which has n=2. But the n=2 electrons see an effective charge of Z − 1, which is the value appropriate for the charge of the nucleus, when a single electron remains in the lowest Bohr orbit to screen the nuclear charge +Z, and lower it by −1 (due to the electron's negative charge screening the nuclear positive charge). The energy gained by an electron dropping from the second shell to the first gives Moseley's law for K-alpha lines,

or

Here, Rv = RE/h is the Rydberg constant, in terms of frequency equal to 3.28 x 1015 Hz. For values of Z between 11 and 31 this latter relationship had been empirically derived by Moseley, in a simple (linear) plot of the square root of X-ray frequency against atomic number (however, for silver, Z = 47, the experimentally obtained screening term should be replaced by 0.4). Notwithstanding its restricted validity,[10] Moseley's law not only established the objective meaning of atomic number, but as Bohr noted, it also did more than the Rydberg derivation to establish the validity of the Rutherford/Van den Broek/Bohr nuclear model of the atom, with atomic number (place on the periodic table) standing for whole units of nuclear charge.

The K-alpha line of Moseley's time is now known to be a pair of close lines, written as (Kα1 and Kα2) in Siegbahn notation.

Shortcomings

The Bohr model gives an incorrect value L=ħ for the ground state orbital angular momentum: The angular momentum in the true ground state is known to be zero from experiment.[11] Although mental pictures fail somewhat at these levels of scale, an electron in the lowest modern "orbital" with no orbital momentum, may be thought of as not to rotate "around" the nucleus at all, but merely to go tightly around it in an ellipse with zero area (this may be pictured as "back and forth", without striking or interacting with the nucleus). This is only reproduced in a more sophisticated semiclassical treatment like Sommerfeld's. Still, even the most sophisticated semiclassical model fails to explain the fact that the lowest energy state is spherically symmetric – it doesn't point in any particular direction.

Nevertheless, in the modern fully quantum treatment in phase space, the proper deformation (careful full extension) of the semi-classical result adjusts the angular momentum value to the correct effective one. As a consequence, the physical ground state expression is obtained through a shift of the vanishing quantum angular momentum expression, which corresponds to spherical symmetry.

In modern quantum mechanics, the electron in hydrogen is a spherical cloud of probability that grows denser near the nucleus. The rate-constant of probability-decay in hydrogen is equal to the inverse of the Bohr radius, but since Bohr worked with circular orbits, not zero area ellipses, the fact that these two numbers exactly agree is considered a "coincidence". (However, many such coincidental agreements are found between the semiclassical vs. full quantum mechanical treatment of the atom; these include identical energy levels in the hydrogen atom and the derivation of a fine structure constant, which arises from the relativistic Bohr–Sommerfeld model (see below) and which happens to be equal to an entirely different concept, in full modern quantum mechanics).

The Bohr model also has difficulty with, or else fails to explain:

- Much of the spectra of larger atoms. At best, it can make predictions about the K-alpha and some L-alpha X-ray emission spectra for larger atoms, if two additional ad hoc assumptions are made. Emission spectra for atoms with a single outer-shell electron (atoms in the lithium group) can also be approximately predicted. Also, if the empiric electron–nuclear screening factors for many atoms are known, many other spectral lines can be deduced from the information, in similar atoms of differing elements, via the Ritz–Rydberg combination principles (see Rydberg formula). All these techniques essentially make use of Bohr's Newtonian energy-potential picture of the atom.

- the relative intensities of spectral lines; although in some simple cases, Bohr's formula or modifications of it, was able to provide reasonable estimates (for example, calculations by Kramers for the Stark effect).

- The existence of fine structure and hyperfine structure in spectral lines, which are known to be due to a variety of relativistic and subtle effects, as well as complications from electron spin.

- The Zeeman effect – changes in spectral lines due to external magnetic fields; these are also due to more complicated quantum principles interacting with electron spin and orbital magnetic fields.

- The model also violates the uncertainty principle in that it considers electrons to have known orbits and locations, two things which cannot be measured simultaneously.

- Doublets and triplets appear in the spectra of some atoms as very close pairs of lines. Bohr's model cannot say why some energy levels should be very close together.

- Multi-electron atoms do not have energy levels predicted by the model. It does not work for (neutral) helium.

Refinements

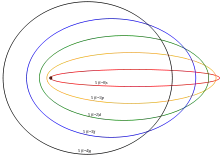

Several enhancements to the Bohr model were proposed, most notably the Sommerfeld or Bohr–Sommerfeld models, which suggested that electrons travel in elliptical orbits around a nucleus instead of the Bohr model's circular orbits.[1] This model supplemented the quantized angular momentum condition of the Bohr model with an additional radial quantization condition, the Wilson–Sommerfeld quantization condition.[12][13]

where pr is the radial momentum canonically conjugate to the coordinate q which is the radial position and T is one full orbital period. The integral is the action of action-angle coordinates. This condition, suggested by the correspondence principle, is the only one possible, since the quantum numbers are adiabatic invariants.

The Bohr–Sommerfeld model was fundamentally inconsistent and led to many paradoxes. The magnetic quantum number measured the tilt of the orbital plane relative to the xy-plane, and it could only take a few discrete values. This contradicted the obvious fact that an atom could be turned this way and that relative to the coordinates without restriction. The Sommerfeld quantization can be performed in different canonical coordinates and sometimes gives different answers. The incorporation of radiation corrections was difficult, because it required finding action-angle coordinates for a combined radiation/atom system, which is difficult when the radiation is allowed to escape. The whole theory did not extend to non-integrable motions, which meant that many systems could not be treated even in principle. In the end, the model was replaced by the modern quantum mechanical treatment of the hydrogen atom, which was first given by Wolfgang Pauli in 1925, using Heisenberg's matrix mechanics. The current picture of the hydrogen atom is based on the atomic orbitals of wave mechanics which Erwin Schrödinger developed in 1926.

However, this is not to say that the Bohr-Sommerfeld model was without its successes. Calculations based on the Bohr–Sommerfeld model were able to accurately explain a number of more complex atomic spectral effects. For example, up to first-order perturbations, the Bohr model and quantum mechanics make the same predictions for the spectral line splitting in the Stark effect. At higher-order perturbations, however, the Bohr model and quantum mechanics differ, and measurements of the Stark effect under high field strengths helped confirm the correctness of quantum mechanics over the Bohr model. The prevailing theory behind this difference lies in the shapes of the orbitals of the electrons, which vary according to the energy state of the electron.

The Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization conditions lead to questions in modern mathematics. Consistent semiclassical quantization condition requires a certain type of structure on the phase space, which places topological limitations on the types of symplectic manifolds which can be quantized. In particular, the symplectic form should be the curvature form of a connection of a Hermitian line bundle, which is called a prequantization.

Bohr also updated his model in 1922, assuming that certain numbers of electrons (for example 2, 8, and 18) correspond to stable "closed shells".[14]

Model of the chemical bond

Niels Bohr proposed a model of the atom and a model of the chemical bond. According to his model for a diatomic molecule, the electrons of the atoms of the molecule form a rotating ring whose plane is perpendicular to the axis of the molecule and equidistant from the atomic nuclei. The dynamic equilibrium of the molecular system is achieved through the balance of forces between the forces of attraction of nuclei to the plane of the ring of electrons and the forces of mutual repulsion of the nuclei. The Bohr model of the chemical bond took into account the Coulomb repulsion – the electrons in the ring are at the maximum distance from each other.[15][16]

See also

|

|

References

Footnotes

- Lakhtakia, Akhlesh; Salpeter, Edwin E. (1996). "Models and Modelers of Hydrogen". American Journal of Physics. 65 (9): 933. Bibcode:1997AmJPh..65..933L. doi:10.1119/1.18691.

- Niels Bohr (1913). "On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules, Part I" (PDF). Philosophical Magazine. 26 (151): 1–24. Bibcode:1913PMag...26....1B. doi:10.1080/14786441308634955.

- Olsen and McDonald 2005

- "CK12 – Chemistry Flexbook Second Edition – The Bohr Model of the Atom". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- Stachel, John (2009). "Bohr and the Photon". Quantum Reality, Relativistic Causality, and Closing the Epistemic Circle. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 79.

- Louisa Gilder, "The Age of Entanglement" The Arguments 1922 p. 55, "Well, yes," says Bohr. "But I can hardly imagine it will involve light quanta. Look, even if Einstein had found an unassailable proof of their existence and would want to inform me by telegram, this telegram would only reach me because of the existence and reality of radio waves." 2009

- "Revealing the hidden connection between pi and Bohr's hydrogen model." Physics World (November 17, 2015)

- Müller, U.; de Reus, T.; Reinhardt, J.; Müller, B.; Greiner, W. (1988-03-01). "Positron production in crossed beams of bare uranium nuclei". Physical Review A. 37 (5): 1449–1455. Bibcode:1988PhRvA..37.1449M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.37.1449. PMID 9899816. S2CID 35364965.

- "Interview of Niels Bohr by Thomas S. Kuhn, Leon Rosenfeld, Erik Rudinger, and Aage Petersen". Niels Bohr Library & Archives, American Institute of Physics. 31 Oct 1962. Retrieved 27 Mar 2019.

- M.A.B. Whitaker (1999). "The Bohr–Moseley synthesis and a simple model for atomic x-ray energies". European Journal of Physics. 20 (3): 213–220. Bibcode:1999EJPh...20..213W. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/20/3/312.

- Smith, Brian. "Quantum Ideas: Week 2" Lecture Notes, p.17. University of Oxford. Retrieved Jan. 23, 2015.

- A. Sommerfeld (1916). "Zur Quantentheorie der Spektrallinien". Annalen der Physik. 51 (17): 1–94. Bibcode:1916AnP...356....1S. doi:10.1002/andp.19163561702.

- W. Wilson (1915). "The quantum theory of radiation and line spectra". Philosophical Magazine. 29 (174): 795–802. doi:10.1080/14786440608635362.

- Shaviv, Glora (2010). The Life of Stars: The Controversial Inception and Emergence of the Theory of Stellar Structure. Springer. p. 203. ISBN 978-3642020872.

- Бор Н. (1970). Избранные научные труды (статьи 1909–1925). 1. М.: «Наука». p. 133.

- Svidzinsky, Anatoly A.; Marlan O. Scully; Dudley R. Herschbach (2005). "Bohr's 1913 molecular model revisited". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (34): 11985–11988. arXiv:physics/0508161. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10211985S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505778102. PMC 1186029. PMID 16103360.

Primary sources

- Niels Bohr (1913). "On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules, Part I" (PDF). Philosophical Magazine. 26 (151): 1–24. Bibcode:1913PMag...26....1B. doi:10.1080/14786441308634955.

- Niels Bohr (1913). "On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules, Part II Systems Containing Only a Single Nucleus" (PDF). Philosophical Magazine. 26 (153): 476–502. Bibcode:1913PMag...26..476B. doi:10.1080/14786441308634993.

- Niels Bohr (1913). "On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules, Part III Systems containing several nuclei". Philosophical Magazine. 26: 857–875. Bibcode:1913PMag...26..857B. doi:10.1080/14786441308635031.

- Niels Bohr (1914). "The spectra of helium and hydrogen". Nature. 92 (2295): 231–232. Bibcode:1913Natur..92..231B. doi:10.1038/092231d0. S2CID 11988018.

- Niels Bohr (1921). "Atomic Structure". Nature. 107 (2682): 104–107. Bibcode:1921Natur.107..104B. doi:10.1038/107104a0. S2CID 4035652.

- A. Einstein (1917). "Zum Quantensatz von Sommerfeld und Epstein". Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft. 19: 82–92. Reprinted in The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, A. Engel translator, (1997) Princeton University Press, Princeton. 6 p. 434. (provides an elegant reformulation of the Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization conditions, as well as an important insight into the quantization of non-integrable (chaotic) dynamical systems.)

Further reading

- Linus Carl Pauling (1970). "Chapter 5-1". General Chemistry (3rd ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman & Co.

- Reprint: Linus Pauling (1988). General Chemistry. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-65622-5.

- George Gamow (1985). "Chapter 2". Thirty Years That Shook Physics. Dover Publications.

- Walter J. Lehmann (1972). "Chapter 18". Atomic and Molecular Structure: the development of our concepts. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-52440-9.

- Paul Tipler and Ralph Llewellyn (2002). Modern Physics (4th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4345-0.

- Klaus Hentschel: Elektronenbahnen, Quantensprünge und Spektren, in: Charlotte Bigg & Jochen Hennig (eds.) Atombilder. Ikonografien des Atoms in Wissenschaft und Öffentlichkeit des 20. Jahrhunderts, Göttingen: Wallstein-Verlag 2009, pp. 51–61

- Steven and Susan Zumdahl (2010). "Chapter 7.4". Chemistry (8th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-495-82992-8.

- Helge Kragh (2011). "Conceptual objections to the Bohr atomic theory — do electrons have a "free will" ?". European Physical Journal H. 36 (3): 327–352. Bibcode:2011EPJH...36..327K. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2011-20031-x. S2CID 120859582.

External links

- Standing waves in Bohr’s atomic model An interactive simulation to intuitively explain the quantization condition of standing waves in Bohr's atomic mode

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bohr model. |