Bovril

Bovril is the trademarked name of a thick and salty meat extract paste similar to a yeast extract, developed in the 1870s by John Lawson Johnston. It is sold in a distinctive, bulbous jar, and also as cubes and granules. Bovril is owned and distributed by Unilever UK. It is similar in appearance to Marmite and Vegemite.

Bovril (250g jar) | |

| Inventor | John Lawson Johnston |

|---|---|

| Inception | 1889 |

| Manufacturer | Bovril Company |

| Current supplier | Unilever |

Bovril can be made into a drink by diluting with hot water or, less commonly, with milk.[1] It can be used as a flavouring for soups, broth, stews or porridge, or as a spread, especially on toast in a similar fashion to Marmite and Vegemite.[2]

Etymology

.jpg.webp)

The first part of the product's name comes from Latin bovīnus, meaning "ox".[3] Johnston took the -vril suffix from Edward Bulwer-Lytton's then-popular novel, The Coming Race (1870), the plot of which revolves around a superior race of people, the Vril-ya, who derive their powers from an electromagnetic substance named "Vril". Therefore, Bovril indicates great strength obtained from an ox.[4]

History

In 1870, in the Franco-Prussian War, Napoleon III ordered one million cans of beef to feed his troops. The task of providing all this beef went to John Lawson Johnston, a Scotsman living in Canada. Large quantities of beef were available across the British Dominions and South America, but its transport and storage were problematic. Therefore, Johnston created a product known as 'Johnston's Fluid Beef', later called Bovril, to meet the needs of Napoleon III.[5] By 1888, over 3,000 UK public houses, grocers and dispensing chemists were selling Bovril. In 1889, Bovril Ltd was formed to develop Johnston's business further.[6]

Bovril continued to function as a "war food" in World War I and was frequently mentioned in the 1930 account Not So Quiet: Stepdaughters of War by Helen Zenna Smith. One account from the book describes it being prepared for the casualties at Mons where "the orderlies were just beginning to make Bovril for the wounded, when the bearers and ambulance wagons were shelled as they were bringing the wounded into the hospital".[7]

A thermos of beef tea was the favoured way to fend off the chill of matches during the winter season for generations of British football fans; Bovril dissolved in hot water is still sold in stadiums all over the United Kingdom. Bovril beef tea was the only hot drink that Ernest Shackleton's team had to drink when they were marooned on Elephant Island during the Endurance Expedition.[8]

When John Lawson Johnston died, his son George Lawson Johnston inherited and took over the Bovril business. In 1929, George Lawson Johnston was created Baron Luke, of Pavenham, in the county of Bedford.

Bovril's instant beef stock was launched in 1966 and its "King of Beef" range of instant flavours for stews, casseroles and gravy in 1971. In 1971, James Goldsmith's Cavenham Foods acquired the Bovril Company but then sold most of its dairies and South American operations to finance further take-overs.[9] The brand is now owned by Unilever.[5]

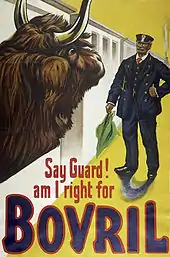

Bovril holds the unusual distinction of having been advertised with a Pope. An advertising campaign of the early 20th century in Britain depicted Pope Leo XIII seated on his throne, bearing a mug of Bovril. The campaign slogan read: The Two Infallible Powers – The Pope & Bovril.

Licensed production

Bovril is also produced in South Africa by the Bokomo division of Pioneer Foods.[10]

During the Siege of Ladysmith in the Second Boer War, a Bovril-like paste was produced from horse meat within the garrison. Nicknamed Chevril (a portmanteau of Bovril and cheval, French for horse) it was produced by boiling down horse or mule meat to a jelly paste and serving it as a "beef tea".[11][12]

Recipe changes

In 2004, Unilever removed beef ingredients from the Bovril formula, rendering it vegetarian. This was mainly due to concerns about decreasing sales, particularly from exports due to an export ban on British beef, as a result of the growing popularity of vegetarianism, religious dietary requirements, and public concerns about bovine spongiform encephalopathy.[13] In 2006, Unilever reversed that decision and reintroduced beef ingredients to their Bovril formula once sales increased and the beef export bans were lifted.[14] Unilever now produces Bovril using beef extract and a chicken variety using chicken extract.[15]

In November 2020, Forest Green Rovers Football Club announced a collaboration with the makers of Bovril to create a beet-based version of Bovril to be sold at their New Lawn stadium, where meat-based products had been removed from sale some years prior.[16]

Cultural significance

Since its invention, Bovril has become an icon of British culture. It is commonly associated with football culture, since during the winter British football fans in stadium terraces often drink it from Thermos flasks; or from disposable cups in Scotland, where thermoses are banned from football stadiums.[17][18]

In the film In Which We Serve, the officers on the bridge are served "Bovril rather heavily laced with sherry" to warm them up, after being rescued during the Dunkirk evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force.

British mountaineer Chris Bonington appeared in TV commercials for Bovril in the 1970s and 1980s in which he recalled melting snow and ice on Everest to make hot drinks.

Video games enthusiast Steve McNeil is touted to be the future ‘Face of Bovril’

See also

References

- "Try Bovril and milk (advert)". The Sydney Mail. 1 July 1931. p. 23.

- Wainwright, Martin. "Bovril drops the beef to go vegetarian". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

In Malaysia they stir it into porridge and coffee

- OED entry at bovine.

- Thompson, William Phillips (1920). Handbook of patent law of all countries. London: Stevens. p. 42. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- "Bovril". Unilever.co.uk. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- "Money-Market and City Intelligence". The Times (32638). London. 5 March 1889. p. 12.

- Vivian, Evelyn Charles (1914). With the Royal army medical corps (R.A.M.C.) at the front. Hodder and Stoughton. p. 99.

- "Shackleton's men kept hope of rescue high; Marooned Scientists, Living on Penguin and Seaweed, Watched Daily for Relief" (PDF). The New York Times. 11 September 1916. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- Goldsmith Archived 5 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Pioneer Foods". pioneerfoods.co.za.

- Watt, S. "Intombi Military Hospital and Cemetery". Military History Journal. Die Suid-Afrikaanse Krygshistoriese Vereniging. 5 (6).

- Jacson, M (1908). "II". The Record of a Regiment of the Line. Hutchinson & Co. p. 88.

- Wainwright, Martin (18 November 2004). "Bovril drops the beef to go vegetarian". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Unilever puts the beef back into Bovril". The Guardian. 1 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Bovril Unilever food brands". Archived from the original on 11 April 2012.

- "Rovers bringing Bovril back". Forest Green Rovers F.C. 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- "Bovril: It's a drink, a spread, even a crisp flavouring, and it was created in Edinburgh". The Scotsman. 8 June 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Alexander Lawrie (7 August 2009). "Tribute to Scots Bovril inventor". Deadline News. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bovril. |

- Official Bovril Website

- Unilever Website

- Unilever explains the reintroduction of beef to Bovril.

- BBC: No beef over Bovril's veggie move

- The Bovril Shrine

- Documents and clippings about Bovril in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW