Brusilov Offensive

The Brusilov Offensive (Russian: Брусиловский прорыв Brusilovskiĭ proryv, literally: "Brusilov's breakthrough"), also known as the "June Advance",[7] of June to September 1916 was the Russian Empire's greatest feat of arms during World War I, and among the most lethal offensives in world history. The historian Graydon Tunstall called the Brusilov Offensive the worst crisis of World War I for Austria-Hungary and the Triple Entente's greatest victory, but it came at a tremendous loss of life.[8] The heavy casualties eliminated the offensive power of the Imperial Russian Army and contributed to Russia's collapse the next year.

| Brusilov Offensive (Брусиловский прорыв) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War I | |||||||

Russian general Aleksei Brusilov, 1916 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Initial: 40+ Infantry divisions (573,000 men) 15 cavalry divisions (60,000 men) Overall: |

Initial: 39 infantry divisions (437,000 men) 10 cavalry divisions (30,000 men) Overall: 1,061,000 in 54 Austrian divisions and 24 German divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

440,000 dead or wounded Total: 500,000–1,000,000 casualties |

Austria-Hungary Total: 760,000–1,337,000 casualties[6] | ||||||

The offensive involved a major Russian attack against the armies of the Central Powers on the Eastern Front. Launched on 4 June 1916, it lasted until late September. It took place in an area of present-day western Ukraine, in the general vicinity of the towns of Lviv, Kovel, and Lutsk. The offensive takes its name after the commander in charge of the Southwestern Front of the Imperial Russian Army, General Aleksei Brusilov.

Background

Under the terms of their Chantilly Agreement of December 1915, Russia, France, Britain and Italy committed to simultaneous attacks against the Central Powers in the summer of 1916. Russia felt obliged to lend troops to fight in France and Salonika (against her own wishes), and to attack on the Eastern Front, in the hope of obtaining munitions from Britain and France.[9]

In March 1916 the Russians initiated the disastrous Lake Naroch Offensive in the Vilnius area, during which the Germans suffered only one-fifth as many casualties as the Russians. This offensive took place at French request - General Joseph Joffre had hoped that the Germans would transfer more units to the East after the Battle of Verdun began in February 1916.[10]

At a war council held with senior commanders and the czar in April 1916, General Aleksei Brusilov presented a plan to the Stavka (the Russian high command), proposing a massive offensive by his Southwestern Front against the Austro-Hungarian forces in Galicia.[11] Brusilov's plan aimed to take some of the pressure off French and British armies in France and the Italian Army along the Isonzo Front and, if possible, to knock Austria-Hungary out of the war.[11] As the Austrian army was heavily engaged in Italy, the Russian army enjoyed a significant numerical advantage in the Galician sector.

Prelude

Plan

General Alexei Evert, commander of the Russian Western Army Group based in Smolensk, favored a defensive strategy and opposed Brusilov's proposed offensive. Emperor Nicholas II had taken personal command of the Imperial Russian army in September 1915. Evert was a strong supporter of Nicholas and the Romanovs, but the Emperor approved Brusilov's plan. The offensive aimed to capture the cities of Kovel and Lviv (in present-day western Ukraine); the Central Powers had recovered both these cities in 1915. Although the Stavka had approved Brusilov's plan, his request for supporting offensives by the neighboring fronts (the Western under Evert and Northern under Aleksey Kuropatkin) was denied.[12]

Offensive preparations

Mounting pressure from the western Allies caused the Russians to hurry their preparations. Brusilov amassed four armies totaling 40 infantry divisions and 15 cavalry divisions. He faced 39 Austrian infantry divisions and 10 cavalry divisions, formed in a row of three defensive lines, as well as German reinforcements that were later brought up.[13]

Deception efforts on the Russian side were intended to conceal the point of attack.[14] They included false radio traffic, false orders sent by messengers who were intended to be captured, and equipment displays including dummy artillery.[13][14]

Brusilov, knowing he would not receive significant reinforcements, moved his reserves up to the front line. He used them to dig entrenchments about 300 by 90 metres (328 yd × 98 yd) along the front line. These provided shelter for the troops and hindered observation by the Austrians.[13] The Russians secretly sapped trenches, and in some places tunnelled, to within 91 metres (100 yd) of the Austrian lines and at some points as close as 69 metres (75 yd). Brusilov prepared for a surprise assault along 480 kilometres (300 mi) of front. Stavka urged Brusilov to shorten his attacking front considerably, to allow for a much heavier concentration of Russian troops, but Brusilov insisted on his plan, and Stavka relented.

Breakthrough

On 4 June 1916, the Russians opened the offensive with a massive, accurate but brief artillery barrage against the Austro-Hungarian lines, with the key factor of this effective bombardment being its brevity and accuracy. This was in contrast to the usual, protracted barrages at the time that gave the defenders time to bring up reserves and evacuate forward trenches while damaging the battlefield so badly that it was hard for attackers to advance. The initial attack was successful, and the Austro-Hungarian lines were broken, enabling three of Brusilov's four armies to advance on a wide front (see: Battle of Kostiuchnówka).

The success of the breakthrough was helped in large part by Brusilov's innovation to attack weak points along the Austrian lines to effect a breakthrough, which the main Russian army could then exploit.

Battle

.jpg.webp)

On 8 June forces of the Southwestern Front took Lutsk. The Austrian commander, Archduke Josef Ferdinand, barely escaped the city before the Russians entered, a testament to the speed of the Russian advance. By now the Austrians were in full retreat and the Russians had taken over 200,000 prisoners. Brusilov's forces were becoming overextended and he made it clear that further success of the operation depended on Evert launching his part of the offensive. Evert, however, continued to delay, which gave the German high command time to send reinforcements to the Eastern Front.

In a meeting held on the same day Lutsk fell, German Chief of Staff Erich von Falkenhayn persuaded his Austrian counterpart Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf to pull troops away from the Italian Front to counter the Russians in Galicia. Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, Germany's commander in the East (Oberkommando-Ost), was again able to capitalize on good railroads to bring German reinforcements to the front.

On 11 June, while pursuing the Austro-Hungarian Army in Bukovina, Russian forces inadvertently crossed into Romanian territory, where they overwhelmed the border guard at Mamornița and had a cavalry patrol disarmed and interned at Herța. Having no intention to force the hand of the Romanian Government, the Russians quickly left Romanian territory.[15][16]

Finally, on 18 June a weak and poorly prepared offensive commenced under Evert. On 24 July Alexander von Linsingen counterattacked the Russians south of Kovel and temporarily checked them. On 28 July Brusilov resumed his own offensive, and although his armies were short on supplies he reached the Carpathian Mountains by 20 September. The Russian high command started transferring troops from Evert's front to reinforce Brusilov, a transfer Brusilov strongly opposed because more troops only served to clutter his front.

Maps

Blue and red lines: Eastern front 1916. Brusilov offensive takes place in lower right corner.

Blue and red lines: Eastern front 1916. Brusilov offensive takes place in lower right corner.

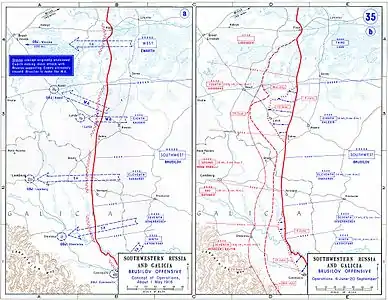

Left: Plan of May. Right: Frontline at the end of Brusilov offensive in September 1916.

Left: Plan of May. Right: Frontline at the end of Brusilov offensive in September 1916.

Russian deportations

From 27 June to 3 July 1916, Brusilov carried out, on his own initiative, the deportation of 13,000 German civilians from the Volhynian areas that had been conquered during the offensive.[17]

Aftermath and Legacy

Brusilov's operation achieved its original goal of forcing Germany to halt its attack on Verdun and transfer considerable forces to the East. Afterward, the Austro-Hungarian army increasingly had to rely on the support of the German army for its military successes. On the other hand, the German army did not suffer much from the operation and retained most of its offensive power afterward.

The early success of the offensive convinced Romania to enter the war on the side of the Entente, which led to the failure of the 1916 campaign. Russian casualties were considerable, numbering between 500,000[1] and 1,000,000.[18] Austria-Hungary and Germany lost from 616,000[19] to 975,000 and from 148,000[20] to 350,000,[21] respectively, making a total of 764,000 to 1,337,000 casualties. The Brusilov Offensive is considered as one of the most lethal offensives in world history.

The Brusilov Offensive was the high point of the Russian effort during World War I, and was a manifestation of good leadership and planning on the part of the Imperial Russian Army coupled with great skill of the lower ranks. According to John Keegan, "the Brusilov Offensive was, on the scale by which success was measured in the foot-by-foot fighting of the First World War, the greatest victory seen on any front since the trench lines had been dug on the Aisne two years before".[22]

The Brusilov offensive commanded by Brusilov himself went very well, but the overall campaign, for which Brusilov's part was only supposed to be a distraction, because of Evert's failures, became tremendously costly for the Imperial army, and after the offensive, it was no longer able to launch another on the same scale. Many historians contend that the casualties that the Russian army suffered in this campaign contributed significantly to its collapse the following year.[23]

The operation was marked by a considerable improvement in the quality of Russian tactics. Brusilov used smaller, specialized units to attack weak points in the Austro-Hungarian trench lines and blow open holes for the rest of the army to advance into. These were a remarkable departure from the human wave attacks that had dominated the strategy of all the major armies until that point during World War I. Evert used conventional tactics that were to prove costly and indecisive, thereby costing Russia its chance for a victory in 1916.

The irony was that other Russian commanders did not realize the potential of the tactics that Brusilov had devised. Similar tactics were proposed separately by French, Germans, and British on the Western Front, and employed at the Battle of Verdun earlier in the year, and would henceforth be used to an even greater degree by the Germans, who utilized stormtroopers and infiltration tactics to great effect in the 1918 Spring Offensive.[24]

Breakthrough tactics were later to play a large role in the early German blitzkrieg offensives of World War II and the later attacks by the Soviet Union and the Western Allies to defeat Germany, and evolved into modern armoured warfare.[25][26]

Citations

- Мерников А. Г., Спектор А.А. Всемирная история войн. — Минск., 2005. - стр. 428

- John Keegan : Der Erste Weltkrieg – Eine europäische Tragödie. 3. Auflage. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2004, S. 425.

- Reichsarchiv: Der Weltkrieg von 1914 bis 1918. Volume 10, Berlin 1936, p. 566.

- Keegan John, (2000). The First World War.

- Turkey In The First World War: Galicia. Turkish losses for September were: unknown on the action of September 2. 7,000 on the actions of September 16/17. 5,000 on the actions of September 30.

- http://elib.shpl.ru/ru/nodes/13726-vetoshnikov-l-v-brusilovskiy-proryv-operativno-strategicheskiy-ocherk-m-1940

- Biography of one of the participants (in Russian)

- Tunstall, Graydon A. (2008). "Austria-Hungary and the Brusilov Offensive of 1916". The Historian. 70 (1): 30–53 [p. 52]. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.2008.00202.x.

- Stone 1998, p221, 252

- Keegan 2000, p325

- Tucker, Spencer (2011). Battles that Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 428. ISBN 978-1-5988-4429-0 – via Google Books.

- Onacewicz, Wlodzimierz (1985). Empires by Conquest: 1905-1945. Fairfax, VA: Hero Books. p. 74. ISBN 978-9-1597-9040-6 – via Google Books.

- Dowling, Timothy C. (2008). The Brusilov Offensive. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 43–46. ISBN 978-0-253-35130-2.

- Buttar, Prit (2016). Russia's Last Gasp: The Eastern Front 1916–17. New York, NY: Osprey Publishing. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-4728-1277-3 – via Google Books.

- Leonard Arthur Magnus, K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company Limited, 1917, Roumania's Cause & Ideals, pp. 118-119

- Glenn E. Torrey, Center for Romanian Studies, 1998, Romania and World War I, p. 113

- Lohr 2003, p. 137.

- John Keegan : Der Erste Weltkrieg – Eine europäische Tragödie. 3. Auflage. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2004, S. 425.

- Kriegsarchiv: Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg. Volume 5, Vienna 1934, p. 218.

- Reichsarchiv: Der Weltkrieg von 1914 bis 1918. Volume 10, Berlin 1936, p. 566.

- Keegan John: The First World War, Vintage Canada, Toronto, 2000.

- Keegan John, (2000). The First World War. P. 306

- Defeat and Disarmament, Joe Dixon

- Edmonds, J. E.; Davies, C. B.; Maxwell-Hyslop, R. G. B. (1935). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1918: The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents, by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. p. 489. ISBN 0-89839-219-5.

- Corum, James S. (1992). The Roots of Blitzkrieg: Hans von Seeckt and German Military Reform. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7006-0541-5.

- Citino, Robert M. (26 December 2007). The Path to Blitzkrieg: Doctrine and Training in the German Army, 1920-39. Stackpole Books. p. 16. ISBN 0811734579.

Bibliography

- Dowling, Timothy C. (2008). The Brusilov Offensive. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253351308.

- Keegan, John (2000). The First World War. Toronto: Vintage Canada. ISBN 0-676-97224-1.

- Lohr, Eric (2003). Nationalizing the Russian Empire: The Campaign against Enemy Aliens during World War I. London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01041-8.

- Stone, Norman (1998) [1975]. The Eastern Front 1914–1917. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-026725-5.

Further reading

- Washburn, Stanley (1917). The Russian offensive, being the third volume of "Field notes from the Russian front," embracing the period from June 5th to Sept. 1st, 1916. London: Constable.

- Harrision, William W. "THE DEVELOPMENT OF RUSSIAN-SOVIET OPERATIONAL ART, 1904-1937, AND THE IMPERIAL LEGACY IN SOVIET MILITARY THOUGHT." (n.d.): n. pag. King's Research Portal. William W. Harrison, May 1994. Web. June 21, 2017 <https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/2928872/319513_.pdf>.

- Clodfelter, Micheal. Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015. 4th ed. Jefferson, page 412, North Carolina: Micheal Clodfelter, 2017. Google Books. Micheal Clodfelter, 2017. Web. 21 June 2017

- Liddell Hart, B.H. (1930). The Real War: 1914–18. pp. 224–227.

- Schindler J. "Steamrollered in Galicia: The Austro-Hungarian Army and the Brusilov Offensive, 1916", War in History, Vol. 10, No. 1. (2003), pp. 27–59.

- Stone, David (2015). The Russian Army in the Great War: The Eastern Front, 1914–1917. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700620951.

- Tucker, Spencer The Great War: 1914–18 (1998) ISBN 978-0-253-21171-2

- Sergei Sergeyev-Tsensky, [1943]. Brusilov's Break-Through: A Novel of the First World War, translated into English by Helen Altschuler, Hutchinson & Co, London, 1945.

- B. P. Utkin Brusilovskij proryv (2001) (in Russian)

- Операция русского Юго-Западного фронта летом 1916 года (in Russian)

- Jukes, Geoffrey (2003). The First World War (I); The Eastern Front 1914–1918. Minneapolis: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-415-96841-0.

- Neiberg, Michael; Jordan, David (2003). History of World War I; The Eastern Front 1914–1920. London: Amber Books. ISBN 0-415-96841-0.

https://www.awm.gov.au/exhibitions/1918/battles/hamel/ Australian commander's offensive: Origins of the "Blitzkrieg" warfare.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brusilov Offensive. |

- Primary Documents: Alexei Brusilov on the Brusilov Offensive, June 1916

- 4 June 1916 - The Brusilov Offensive on Trenches on the Web

- http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_kovel_stanislav.html

- Map of Europe during the Brusilov Offensive at omniatlas.com