German occupation of Belgium during World War I

The German occupation of Belgium (French: Occupation allemande, Dutch: Duitse bezetting) of World War I was a military occupation of Belgium by the forces of the German Empire between 1914 and 1918. Beginning in August 1914 with the invasion of neutral Belgium, the country was almost completely overrun by German troops before the winter of the same year as the Allied forces withdrew westwards. The Belgian government went into exile, while King Albert I and the Belgian Army continued to fight on a section of the Western Front. Under the German military, Belgium was divided into three separate administrative zones. The majority of the country fell within the General Government, a formal occupation administration ruled by a German general, while the others, closer to the front line, came under more repressive direct military rule.

The German occupation coincided with a widespread economic collapse in Belgium with shortages and widespread unemployment, but also with a religious revival. Relief organisations, which relied on foreign support to bring food and clothing to Belgian civilians, cut off from imports by the Allied naval blockade and the fighting, also became extremely important to the social and cultural life of the country.

The German occupation administration repressed political dissent and launched numerous unpopular measures, including the deportation of Belgian workers to Germany and forced labour on military projects. It also supported the radical Flemish Movement by making numerous concessions as part of the Flamenpolitik in an attempt to gain support among the country's Flemish population. As a result, numerous resistance movements were founded which attempted to sabotage military infrastructure, collect intelligence for the Allies or print underground newspapers. Low-level expressions of dissent were common but frequently repressed.

From August 1918, the Allies advanced into occupied Belgium during the Hundred Days Offensive, liberating some areas. For most of the country, however, the occupation was only brought to an end in the aftermath of the armistice of November 1918 as the Belgian Army advanced into the country to replace evacuating German troops in maintaining law and order.

Background

Following its independence in 1830, Belgium had been obliged to remain neutral in perpetuity by an 1839 treaty as part of a guarantee for its independence. Before the war, Belgium was a constitutional monarchy and was noted for being one of the most industrialised countries in the world.[1] On 4 August 1914, the German army invaded Belgium just days after presenting an ultimatum to the Belgian government to allow free passage of German troops across its borders.[2] The German army advanced rapidly into Belgium, besieging and capturing the fortified cities of Liège, Namur and Antwerp and pushing the 200,000-strong Belgian army, supported by their French and British allies, to the far west.[3] Large numbers of refugees also fled to neighbouring countries. In October 1914, the German advance was finally stopped near the French border by a Belgian force at the Yser and by a combined Franco-British force at the Marne. As a result, the front line stabilised with most of Belgium already under German control. In the absence of any decisive offensive, most of Belgium remained under German control until the end of the war.[4]

While most of Belgium was occupied, King Albert I continued to command the Belgian Army along a section of the Western Front, known as the Yser Front, through West Flanders from his headquarters in Veurne.[5] The Belgian government, led by Charles de Broqueville, established itself in exile in Le Havre, in northwestern France. Belgium's colonial possession in Africa, the Belgian Congo, also remained loyal to the Allies and the Le Havre government.

The Rape of Belgium

During the course of their advance through Belgium, the Germans committed a number of war crimes against the Belgian civilian population along their route of advance.[6] The massacres were often responses to towns whose populations were accused of fighting as francs-tireurs or guerillas against the German army.[7] Civilians were summarily executed and several towns deliberately destroyed in a series of punitive actions collectively known as The Rape of Belgium. As many as 6,500 people were killed by the German army between August and November 1914. In Leuven, the historic library of the town's university was deliberately burned. News of the atrocities, also widely exaggerated by the Allied press, raised considerable sympathy for the Belgian civilian population in occupied Belgium. The sympathy for the plight of Belgian civilians and Belgian refugees continued in Allied newspapers and propaganda until the end of the war.[8]

Administration and governance

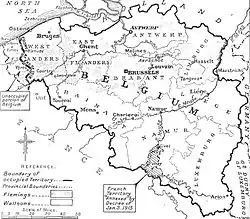

By November 1914, the vast majority of Belgian territory (2,598 out of 2,636 communes) was under German occupation.[9] From November 1914, occupied Belgium, together with the occupied French border areas of Givet and Fumay, was divided by the Germans into three zones.[10] The first, the Operationsgebiet (Operational Zone), covered a small amount of territory near the front line in the far west of Belgium. Near this zone was the Etappengebiet (Staging Zone), covering most of East and West Flanders along with parts of Hainaut and Luxembourg. The remainder of the country, the largest of the zones, the Generalgouvernement (General Government) covered the majority of the country and the French territories.[11] Unlike the Operational and Staging Zones, the General Government was intended to be a total administration and so was markedly less repressive that the other two zones whose governance was based on military concerns alone.[11] Civilians in the Operational and Staging Zones were officially classed as "prisoners" by the German military.[12]

The General Government was placed under the command of a German general who was accountable to the army. After a brief tenure by Colmar von der Goltz in 1914, command was held by Moritz von Bissing and later, from April 1917, by Ludwig von Falkenhausen.[11] The German authorities aimed to use the occupation to benefit the German economy and industrial production but hoped to keep the Belgian state and economy functioning if it did not impede their main objectives.[13]

Administratively, the German administration had a Zivilverwaltung (Civil Administration) tasked with dealing with day-to-day matters and a network of local Kommandanturen in towns and cities across Belgium. It could also call on up to 80,000 soldiers.[11] In most cases, however, the administration was content to use the existing Belgian civil service and local government for much of its administration.[14]

Life under the occupation

Shortages and relief organisations

Before the war, Belgium had been a net importer of foodstuffs. The German invasion, together with the Allied blockade meant that as early as September 1914, various Belgian organisations had been preparing for the onset of famine in the occupied territory. Under the direction of a financier, Émile Francqui, and other philanthropists established the Comité National de Secours et d'Alimentation (CNSA or the "National Relief and Food Committee") to secure and transport food to Belgium, where it could be sold to Belgian civilians.[15] The profits from this part of the operation were then used to distribute aid. After negotiations with both the Allies and Central Powers, the CNSA managed to secure permission to import food from the neutral United States. Francqui used his acquaintance with Herbert Hoover, the future American president, to collect food and other relief through an American organisation, the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), which was then distributed within Belgium by the CNSA.[16] A number of smaller relief organisations affiliated to other neutral countries also worked within occupied Belgium.

The CNSA became a major part of everyday life and culture in occupied Belgium. The organisation fulfilled much of the day-to-day running of a welfare system and generally prevented famine, although food and material shortages were extremely common throughout the occupation.[17] At its height, the CNSA had more than 125,000 agents and distributors across the country.[18] Historians have described the CNSA itself, with its central committee and local networks across the country, as paralleling the actions of the official Belgian government in peacetime.[19] In the eyes of contemporaries, the CNSA became a symbol of national unity and of passive resistance.[19]

Economic life

At the start of the war, the Belgian government hurriedly removed silver coins from circulation and replaced them with banknotes.[20] With the German occupation, these banknotes remained legal and their production continued. To offset the costs of occupation, the German administration demanded regular "war contributions" of 35 million Belgian francs each month.[21] The contribution considerably exceeded Belgium's pre-war tax income and so, in order to pay it, Belgian banks used new paper money to buy bonds.[21] The excessive printing of money, coupled with large amounts of German money brought into the country by soldiers, led to considerable inflation.[20] The Germans also artificially fixed the exchange rate between the German mark and the Belgian franc to benefit their own economy at a ratio of 1:1.25.[20] To cope with the economic conditions, large numbers of individual communes and regions began to print and issue their own money, known as Necessity Money (monnaie de nécessité), which could be used locally.[20]

Fiscal chaos, coupled with problems of transportation and the requisition of metal led to a general economic collapse as factories ran out of raw materials and laid off workers.[20] The crisis especially afflicted Belgium's large manufacturing industries.[22] As raw material usually imported from abroad dried up, more firms laid off workers.[23] Unemployment became a major problem and increased reliance on charity distributed by civil institutions and organisations. As many as 650,000 people were unemployed between 1915 and 1918.[12][24] The German authorities used the crisis to loot industrial machinery from Belgian factories, which was either sent to Germany intact or melted down. The policy escalated after the end of the German policy of deportation in 1917 which later created major problems for Belgian economic recovery after the end of the war.[25]

Religious life

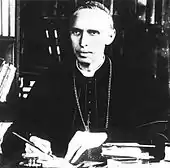

The occupation coincided with a religious revival in Belgium, which had always been overwhelmingly Catholic.[26] The Primate of Belgium, Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier, became an outspoken critic of the German occupation regime. Mercier published a celebrated pamphlet, Patriotisme et Endurance (Patriotism and Endurance), on Christmas Day 1914 which called for civilians to observe occupation laws if they were consistent with Belgian patriotism and Christian values.[26] The pamphlet attacked the authority of the German occupying government, stating that any rule legitimised by force alone should not be obeyed.[27]

In the absence of the King or government in occupied Belgium, Mercier became the predominant figure in the country and a symbol of resilience.[28] Because of his status, he could not be arrested without an outcry, and although he was lured back to the Vatican in 1915 to remove him from the country, he soon returned. His writings were banned, however, and copies of their work confiscated.[29] In 1916, Mercier was officially prohibited from publishing pamphlets but continued to campaign against the deportation of workers and various other German policies.[30] Initially opposed by Pope Benedict XV, who was anxious to remain neutral, the Pope was supportive of the Belgian church but encouraged it to moderate its stance to avoid confrontation.[31]

German policies

Deportation and forced labour

.jpg.webp)

The conscription of German men at the start of the war created a manpower shortage in German factories important for the war effort. From 1915, the Germans encouraged Belgian civilians to enlist voluntarily to work in Germany but the 30,000 recruits of the policy proved insufficient to meet demands.[12]

By mid 1916, the situation was becoming increasingly pressing for the German army. With the appointment of Erich Ludendorff to commander of the General Staff, the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL), in August 1916, the German administration began actively considering the idea of forcibly deporting Belgian workers to Germany to resolve the problem.[32] The policy, encouraged by the high levels of unemployment in occupied Belgium, marked a wider turn towards more oppressive rule by the German administration.[12][32] The deportation began in October 1916 and lasted until March 1917.[12] In all, as many as 120,000 workers had been deported to Germany by the end of the war.[33][32] Of these, around 2,500 died from the poor conditions in which the workers were held.[32] In addition, in the Staging Zone, around 62,000 workers were conscripted as forced labour on local military projects in poor conditions.[12]

The deportation of Belgian workers proved insufficient to meet German industrial needs and had little effect economically.[34] Politically, however, it led to widespread condemnation in Belgium and internationally, helping the rise of the resistance.[34] In late 1917, under pressure from neutral powers, most of the Belgian deported workers were returned.[35]

Flemish Movement and the Flamenpolitik

In the years leading up to the outbreak of the war, the Flemish Movement had become increasingly prominent in Belgian politics. French had traditionally been the dominant language of government and the upper class of Belgian society. After a period of marginalisation, the Flemish Movement succeeded in achieving increased status for Dutch language, one of the movement's chief objectives, culminating in the legal recognition of Dutch as a national language in 1898. In 1914 new laws were passed giving further concessions to the movement, but the outbreak of war meant that their implementation had been postponed. Numerous grievances were left unaddressed.[36] Among the outstanding grievances was the University of Ghent which, though situated in largely Dutch-speaking Flanders, taught exclusively in French.[36]

In 1915, the Governor General decided to launch the Flamenpolitik (Flemish Policy) to use the animosity between the two language groups to facilitate the administration of the territory and to portray the occupation regime as the liberation of Flanders.[37] It was also hoped that it would give Germany some form of influence within the neutral Netherlands.[38] The policy was especially advocated by pan-Germanists, like the Alldeutscher Verband, who believed that the Flemish shared racial traits with the Germans that the Walloons did not.[39] The policy achieved support among some demographics, particularly among young Flemish students within the Flemish Movement.[37] Initially, the Flamenpolitik was restricted to implementing the 1914 language laws, but became increasingly more radical.[36] The Germans also reached out to the comparable Walloon Movement, but with much less success.[40] In 1916, the Germans opened a new university in Ghent, dubbed Von Bissing University, in which all teaching was in Dutch. The new university was welcomed by some but encountered opposition from within the Flemish Movement and few ever enrolled in it.[41][42] The policies divided the Flemish Movement between the radical "activists" (activisten or maximalisten), who welcomed the German measures and believed German support was essential to realising their objectives, and the "passivists" (passivisten), who opposed the Germans and worried that this might discredit the movement.[43] In particular, the activisten hoped that Flemish independence could be realised with German support.[43]

In February 1917, a Raad van Vlaanderen (RVV or the "Council of Flanders") was formed with tacit German support.[43] Its members, all activisten, were broadly supported by the Germans but were condemned by other flamingants and the Church.[43] The Germans subsequently made Flanders and Wallonia separate administrative regions in June 1917. On 22 December 1917, without prior consultation with the occupation authorities, the RVV declared Flanders to be independent and dissolved itself to prepare for elections for a new Flemish government.[43][44] The German authorities viewed the declaration ambivalently and in January 1918 rejected a draft Flemish constitution presented by the RVV.[44] 50,000 people registered to vote in the coming elections but there were clashes with opponents in Mechelen, Antwerp and Tienen.[43] The Belgian court of appeal sent out warrants for the arrest of two leading members of the council, Pieter Tack and August Borms, but the Germans freed them and instead deported the judges responsible. In protest, judges at the Court of Cassation, the Belgian supreme court, refused to try cases and other judges also went on strike.[45] Faced with mounting opposition, the Germans stopped the planned elections in March 1918.[46]

Political repression

Public opposition to the German occupiers was heavily repressed. Displays of patriotism, such as singing the national anthem, La Brabançonne, or celebrating Belgian National Day were banned and those breaking the rules risked strict prison sentences.[47] Newspapers, books and mail were all tightly censored and regulated.[47] Numerous high-profile Belgian figures, including Adolphe Max, the mayor of Brussels, and the historian Henri Pirenne, were imprisoned in Germany as hostages. The aftermath of the Battle of Verdun in 1916 marked a turning point in the occupation and was followed by more repressive measures by the administration, including the deportation of workers to Germany.[32]

From the time of the invasion, significant numbers of Belgian men had attempted to flee the occupied territories to join the Belgian army on the Yser front, via the Netherlands which were neutral.[22] To stop this, the Germans began work on a barbed wire and electric fence across the length of the border. The fence, dubbed the Wire of Death (Dodendraad), was also guarded by German sentries.[48] Between 2,000 and 3,000 civilians are believed to have been killed attempting to cross the border during the conflict.

Captured resistance members were also executed by the German authorities. Famously, Edith Cavell, a British nurse who had lived in Belgium before the war, was arrested after helping Allied soldiers to escape the country and was executed by a German firing squad in 1915. Another résistante, Gabrielle Petit, who had participated in various forms of resistance activity, was executed in 1916 at the Tir national in Schaerbeek and became a posthumous national heroine.[49]

Resistance

A resistance movement developed in Belgium soon after the German occupation. Around 300 separate networks existed, often including male and female members.[50] Resistance took various forms. Although some sabotages by the resistance, notably the destruction of the Brussels-Aachen railway line, were celebrated at the time, armed resistance represented a minority of their acts.[50]

In particular, intelligence gathering played a major role. Around 6,000 Belgian civilians were involved in gathering intelligence on German military installations and troop movements and communicating it back to the Allied armies.[14] The organisation was run through a large number of independent groups and included, notably, the large Dame Blanche (White Lady) network.[50] Alongside intelligence gathering were similar organisations which helped men wishing to join the Belgian Army on the Yser Front to escape occupied Belgium, usually across the Dutch border. Around 32,000 were successfully smuggled out which boosted the size of the Belgian force considerably.[50]

In addition, underground newspapers also formed a big part of resistance activity. The newspapers provided information censored in the approved press and also patriotic propaganda.[51] Some underground papers, most notably La Libre Belgique (The Free Belgium) and De Vlaamsche Leeuw (The Flemish Lion), could reach large numbers of people.[26] Underground newspaper were produced in a variety of formats and geographic areas, sometimes targeting specific demographics.[17] At its height, La Libre Belgique had 600 individual contributors.[50]

The majority form of opposition, however, was passive resistance. Small patriotic badges, depicting the royal family or national colours, were extremely popular.[52] When these symbols were banned, new ones, such as ivy leaves, were worn with similar meaning. Workers in strategic industries deliberately underperformed in their jobs as a form of resistance.[53] The celebration of nationalist public holidays, like 21 July (National Day), which were officially banned by the Germans, were also often accompanied by protests and demonstrations. One of the most notable acts of passive resistance was the Judges' Strike of 1918, which managed to gain concessions from the German occupiers under considerable public pressure.[45]

End of the occupation

By 1918, civilian morale in occupied Belgium reached an all-time low. The early successes of the Ludendorff Offensive (21 March – 18 July 1918) were believed to have made liberation virtually impossible in the foreseeable future.[32] However, during the Hundred Days Offensive (8 August to 11 November 1918), the Allied and Belgian armies launched a series of successful offensives on the Western Front. The Belgian army, restricted to the Yser salient since 1914, advanced as far as Bruges. German forces on the front in Belgium were forced to retreat.

Following a mutiny in Kiel at the end of October, a wave of revolutions broke out within the German army. In occupied Belgium, soldiers of the Brussels garrison mutinied against their officers on 9 November 1918. The revolutionaries formed a Soldiers' Council (Soldatenrat) and flew the red flag over the Brussels Kommandantur while many officers, including the Governor-General, left the city for Germany. Fighting in the streets soon broke out between German loyalists and revolutionaries.[54] With the German police no longer keeping order, anarchy broke out in the city, which was restored only when Belgian troops arrived.[54]

On 11 November 1918, the German army signed an armistice. The ceasefire did not, however, lead to the immediate liberation of Belgium: the terms of the armistice set a timescale for German withdrawal to avoid clashes with the retreating army. Nevertheless sporadic fighting continued.[55] The Belgian army gradually advanced into the country, behind the evacuating German occupying force. The remaining German forces in Belgium moved eastwards towards the German border, gradually evacuating more territory. The final German troops left the country on 23 November.[54]

On 22 November, Albert I entered Brussels with the Belgian army of the Yser in a Joyous Entry. He was widely acclaimed by the civilian population.[56] Subsequently, some of the notable activisten from the RVV were put on trial, but although the body had professed as many as 15,000 followers, only 312 individuals were convicted of collaboration with the enemy. Among them was Borms, who, from prison, would continue to play an important role in the Flemish Movement in the 1920s.[57] In total, 40,000 Belgian soldiers and civilians were killed and 77,500 wounded during World War I.[58]

See also

Notes and references

References

- Hobsbawm 1995, pp. 41–2.

- Kossmann 1978, pp. 520–1.

- Kossmann 1978, pp. 521–2.

- Kossmann 1978, pp. 523–4.

- Kossmann 1978, p. 524.

- De Schaepdrijver 2014, pp. 47–8.

- Kramer 2007, pp. 1–27.

- Zuckerman 2004, pp. 140–1.

- De Schaepdrijver 2014, p. 46.

- Dumoulin 2010, pp. 113–4.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 114.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 131.

- Zuckerman 2004, p. 113.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 115.

- Dumoulin 2010, pp. 120–1.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 122.

- De Schaepdrijver 2014, pp. 52–3.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 123.

- Dumoulin 2010, pp. 122–6.

- BNB Museum 2013.

- Zuckerman 2004, p. 94.

- Kossmann 1978, p. 525.

- Kossmann 1978, p. 528.

- Kossmann 1978, p. 529.

- Kossmann 1978, pp. 533–4.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 127.

- De Schaepdrijver 2014, pp. 48–9.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 129.

- De Schaepdrijver 2014, p. 50.

- Dumoulin 2010, pp. 128–30.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 128.

- De Schaepdrijver 2014, p. 54.

- Cook 2004, pp. 102–7.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 132.

- Kossmann 1978, p. 533.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 133.

- De Schaepdrijver 2014, p. 51.

- Hermans 1992, p. 18.

- Kossmann 1978, p. 526.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 136.

- Dumoulin 2010, pp. 133–4.

- Hermans 1992, pp. 18–9.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 134.

- Zuckerman 2004, p. 197.

- Dumoulin 2010, pp. 134–5.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 135.

- Zuckerman 2004, p. 98.

- De Schaepdrijver 2014, p. 53.

- Zuckerman 2004, p. 117.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 125.

- Dumoulin 2010, p. 125; 127.

- Zuckerman 2004, p. 100.

- Kossmann 1978, pp. 525, 528–9.

- RTBF 2014.

- La Libre Belgique 2008.

- De Schaepdrijver 2014, p. 55.

- Hermans 1992, p. 19.

- Zuckerman 2004, p. 220.

Bibliography

- Cook, Bernard A. (2004). Belgium: A History. Studies in Modern European History (3rd ed.). New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-7647-6.

- De Schaepdrijver, Sophie (2014). "Violence and Legitimacy: Occupied Belgium, 1914–1918". The Low Countries: Arts and Society in Flanders and the Netherlands. 22: 46–56. OCLC 948603897.

- Dumoulin, Michel (2010). L'Entrée dans le XXe Siècle, 1905–1918 [The Beginning of the XX Century, from 1905–1918]. Nouvelle Histoire de Belgique (French ed.). Brussels: Le Cri édition. ISBN 978-2-8710-6545-6.

- "En Belgique, le 11 novembre 1918 ne fut pas un vrai jour de joie" [In Belgium, 11 November 1918 was not a true Day of Joy] (in French). La Libre Belgique. J. C. M. 10 November 2008. OCLC 900937732. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- Hermans, Theo (1992). The Flemish Movement: A Documentary History, 1780–1990. London: Athlone Press. ISBN 978-0-485-11368-6.

- Hobsbawm, Eric (1995). The Age of Empire, 1875–1914. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-81635-5.

- Kossmann, E. H. (1978). The Low Countries, 1780–1940. Oxford History of Modern Europe (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822108-1.

- Kramer, Alan (2007). Dynamic of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280342-9.

- "La fin de la guerre et la retraite" [The End of War and Retirement]. rtbf.be (in French). RTBF. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- "Le Centenaire de la Grande Guerre: La Banque nationale en temps de guerre" [The Centenary of First World War: The National Bank in Times of War] (in French). National Bank of Belgium Museum. 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Zuckerman, Larry (2004). The Rape of Belgium: the Untold Story of World War I. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9704-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to German occupation of Belgium during World War I. |

- Belgian War Press at Cegesoma

- Brussels 14–18 at Brussels-Capital Region

- Occupations during the War (France and Belgium) at the International Encyclopedia of the First World War

- Het dagelijks leven tijdens de eerste wereldoorlog (PDF) at the Official Website of Flanders