Buddha (album)

Buddha is a demo album by the American rock band Blink-182. Recorded and released in January 1994 under the name Blink, it was the band's first recording to be sold and distributed. Blink-182 was formed in Poway, California, a suburb outside of San Diego, in August 1992. Guitarist Tom DeLonge and Mark Hoppus were introduced to one another by Hoppus' sister. The duo recruited drummer Scott Raynor and began to practice together in his bedroom, spending hours together writing music, attending punk shows and movies and playing practical jokes. The band had recorded two previous demos in Raynor's bedroom — Flyswatter and Demo No.2 — using a four track recorder. Most of the tracks from Buddha were re-recorded for the band's subsequent releases; seven were re-recorded for their debut album Cheshire Cat and one was re-recorded for their second album Dude Ranch.

| Buddha | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Demo album by | ||||

| Released | January 1994 (original) October 27, 1998 (re-issue) | |||

| Recorded | January 1994 | |||

| Studio | Doubletime Studios, Santee, California[1] | |||

| Genre | Skate punk | |||

| Length | 35:49 31:55 (re-issue) | |||

| Label | Filter (original) Kung Fu (re-issue) | |||

| Producer | Pat Secor | |||

| Blink-182 chronology | ||||

| ||||

The demo was originally released on the label Filter Records. In the early days of the band, Hoppus worked at the record store The Wherehouse, and became friends with his supervisor, Pat Secor. Hoping to start his own record label, Secor pulled money from his savings and helped finance and produce Buddha. The demo was recorded live at local Santee studio Doubletime, comprising nearly all of the songs the trio had written up to that point. Hoppus and friends Cam Jones and Kerry Key photographed the cassette inserts, and the original packaging was compiled by the band and Hoppus' family. Upon completion, the demo was locally distributed to several San Diego record stores, and was available for purchase at early concerts. Buddha helped the trio cement an audience and was a deciding factor in their signing to local label Cargo in 1993.

The recording became the subject of a legal dispute between the band and Secor several years later. The group accused Secor of selling the tape without paying royalties, and attempted to put a stop to his distribution with help of lawyer Joe Escalante of The Vandals, who also owned independent record label Kung Fu Records. Kung Fu remixed and remastered the demo, giving it a wider commercial reissue in October 1998. This edition deletes two original tracks for other recordings from the original session. Kung Fu has since reportedly sold 300,000 copies of Buddha. It is currently their only commercially available demo. In announcing the band's 2019 album Nine, Hoppus stated that he counted their studio albums beginning with Buddha.

Background

Blink-182 was formed in Poway, California, a suburb outside of San Diego, in August 1992. After Mark Hoppus graduated from high school in Ridgecrest, he relocated to San Diego to work at a record store and attend college.[2] Tom DeLonge was kicked out of Poway High for attending a basketball game drunk and was forced to attend another local school for one semester. At Rancho Bernardo High School, he befriended Kerry Key, also interested in punk music. Key's girlfriend, Anne Hoppus, introduced her brother Mark to DeLonge on August 2, 1992.[2] The two bonded instantly and played for hours in DeLonge's garage, exchanging lyrics and co-writing songs—one of which became "Carousel".[2] DeLonge recruited friend Scott Raynor for drums, whom he met at a Rancho Bernado Battle of the Bands competition.[3] Raynor was by far the youngest member of the trio at 14, and his event account differs significantly: he claims he and DeLonge formed the group after meeting at the Battle of the Bands and worked through a variety of bassists before meeting Hoppus.[3]

The trio began to practice together in Raynor's bedroom, spending hours together writing music, attending punk shows and movies, and playing practical jokes.[3] Hoppus and DeLonge would alternate singing vocal parts. The trio first operated under a variety of names, including Duck Tape and Figure 8, until DeLonge rechristened the band "Blink".[4] Hoppus' girlfriend was angered by her boyfriend's constant attention for the band and demanded him to make a choice between the band and her, which resulted in Hoppus leaving the band shortly after formation.[5] Shortly thereafter, DeLonge and Raynor borrowed a four track recorder from friend and collaborator Cam Jones and were preparing to record a demo tape, with Jones on bass.[4] Hoppus promptly broke up with his girlfriend and returned to the band.[5] Flyswatter—a combination of original songs and punk covers—was recorded in Raynor's bedroom in May 1993.[6] Southern California had a large punk population in the early 1990s, aided by an avid surfing, skating and snowboarding scene.[7] In contrast to East Coast punk music, the West Coast wave of groups, Blink included, typically introduced more melodic aspects to their music.[7] "New York is gloomy, dark and cold. It makes different music. The Californian middle-class suburbs have nothing to be that bummed about," said DeLonge.[7] San Diego at this time was "hardly a hotbed of [musical] activity", but the band's popularity grew as did California punk rock concurrently in the mainstream.[6]

The band's first performance was at a local high school during lunch, and soon the trio graduated to San Diego's Spirit Club and influential local shop Alley Kat Records.[8] DeLonge called clubs constantly in San Diego asking for a spot to play, as well as calling up local high schools convincing them that Blink was a "motivational band with a strong anti-drug message" in hopes to play at an assembly or lunch.[9] The band soon became part of a circuit that also included the likes of Ten Foot Pole and Unwritten Law, and they found their way onto the bill as the opening band for local acts at SOMA, a local all-ages venue which they longed to headline.[7] The band's equipment was piled into a blue station wagon for touring purposes and they first began to play shows outside San Diego.[10]

Recording and production

Buddha was financed by Pat Secor, Hoppus' boss at Wherehouse Music in San Diego. Secor wanted to start his own record label and offered to help pay for costs. "He was like, hey, I'll front you the money, and we'll split the profits until you pay me back," recalled Hoppus in 2001.[11] The two had met when Secor transferred from a north San Diego location. The two became friends quickly, despite Secor's seniority of post.[12] "At that point they'd played around enough to get their chops up so I took all the money I had in savings and we went into the studio for two days," said Secor.[12]

The recording sessions at Doubletime Studios in Santee, California took place in January 1994, and were scheduled around work and school commitments. Hoppus was sick at the time of recording.[13] Despite this, the band carried on and the demo was complete within two days. "Buddha was cut live then we added the vocals. Two days and they were done – including the mix. It's quite standard for a young punk band to do that," said engineer Jeff Forrest.[13] Despite this, the liner notes for the cassette claim it was recorded in twelve hours,[1] while the later remaster of Buddha contend it was recorded "over three rainy nights."[11][14] The trio were "super stoked" about a sound effects tape they found at the studio, and took time out to add in applause and laughter tracks because they deemed it humorous.[11]

Hoppus and DeLonge took the songwriting for their first legitimate release very seriously. The two strove for perfection writing songs that they felt would be relatable.[11] Blink also recorded joke tracks, as they felt that, in addition to the serious songs, "it was almost as important to make people laugh." DeLonge recalled that the band spent more time at the end of production on Buddha trying to perfect the joke songs rather than their serious tracks.[11] The band's main influence on Buddha, according to DeLonge, was the Descendents. "I was trying to emulate that band. Really punchy guitars, fast, simple and formulaic nursery rhyme love songs," he said in 2012.[15]

Packaging and release

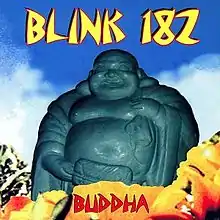

The photographs in the original cassette release of Buddha were photographs taken by friend of the band Cam Jones.[11] Kerry Key, drummer for the Iconoclasts and friend of the band, also is credited with artwork in the original cassette.[1] To produce the artwork, Hoppus and Jones spent an afternoon together taking "artsy" photographs in and around Raynor's backyard.[11] The cover art is a picture of a Buddha statue, which was a present from Hoppus' stepfather that the bassist grabbed on the way to Raynor's for the photos. After developing the photos, they took them to a copy shop to run off color copies. Afterwards, they cut, pasted and rearranged them until they found something suitable. The lyric sheets were handwritten and photocopied.[11] Hoppus and his family in Ridgecrest would spend hours folding and combining pieces of artwork to compile the Buddha cassette. When this was complete, Hoppus would load the cassettes into his car and deliver them to local record stores around town.[16]

"I totally remember driving around to all the record stores to drop off tapes to sell. I'd go to Lou's Records, and Off the Record, and Music Trader. It was so cool because the tapes were actually selling, that's why I had to keep going back every week. Music Trader would have sold one copy, Off the Record sold two, or whatever. But that meant people were actually walking into a music store and buying something we had written and recorded. It was awesome."

The demo tape, which was originally untitled, came to be known by the name Buddha, and was released by Filter Records in 1994.[14] Cassette copies of Buddha were also sold at early Blink concerts, alongside homemade T-shirts.[16]

Re-release

The rights to Buddha and its associated recordings were the subject of a dispute between the band and Secor in later years. According to Secor, he and the band had a gentleman's agreement: he would pay for the costs of recording and manufacturing the tape, and in exchange would receive half of all the profits from it. According to Raynor, the oral agreement was that Secor would invest $1,000 and when that money was recouped, the band would have complete ownership of the work product.[17] Secor helped the band sign to Cargo Music in 1994 using his connections at the label; he felt that by helping the briskly growing band sign a deal he could build his own label, Filter Records, in the wake of Blink's success. According to Secor, he attempted to contact the band to discuss the rights to the tape, but would only receive comments such as "Oh, let me call my manager and I'll call you right back."[17] Secor asserted he should have the rights to the master tapes, having financed the entire production. He alleged that Cargo Music began calling him and making threats, and he could not afford to fight back and was unlikely to win since he had no written contract with the band. In 1996, Blink-182 signed a joint-venture deal with major label MCA Records, who Secor also said began calling him. "Try going up against that," he remarked in 2001.[17]

The band began to grow suspicious that Secor was keeping all the money from selling copies of the Buddha cassette, and contacted their lawyer, Joe Escalante of the Vandals, who also owned independent record label Kung Fu Records. They informed Escalante that they believed "someone's bootlegging it," and requested his legal help to stop Secor.[17] In exchange for legal fees, Blink-182 would allow Kung Fu Records to re-release Buddha on compact disc.[17] The band had told Secor not to sell any more copies of the cassette, but suspected that he was still doing so. Escalante anonymously ordered a tape from Secor, and Secor sold it to him.[17] Blink-182 asserted that they were not receiving royalties for these sales. "I paid off all of the royalties for the remaining stash of tapes that I had of Buddha," said Secor in 2001.[17] "It was about 25. The tapes sold for five bucks, and I gave them half of what their profit would be. I wanted to have a few to give to people and to have on hand." Secor felt it was his right to sell his stock of the cassettes, since the band "had been paid royalties for that already."[17]

Kung Fu re-released Buddha on CD and cassette in November 1998, and has since re-released the recording on vinyl and retains digital distribution. The remaster cleans and sharpens the sound of tracks, and contains a slightly different track listing. "They'd already sold 60,000 copies of Cheshire Cat, said Escalante, "and I thought, 'Man, if I can sell just 10% of that that would be great for the label,' and of course it sold a lot more because they went on to be superstars."[18] In 2001 the label had reportedly sold 300,000 copies of Buddha.[17] "At this point it's not even the money," Secor said at the time. "It's the fact that there is no mention of my work anywhere; no credit has been given to me."[17]

Reception

Reviewing the 1998 re-release of Buddha for AllMusic, critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine rated it three stars out of five, calling it a "promising debut" and "a solid skatepunk record that illustrates the group's flair for speedy, catchy hooks and irreverent humor."[19] Rolling Stone viewed it, alongside proper debut album Cheshire Cat (1995) as "slapped together lilting melodies and racing beats in an attempt to connect emo and skate punk, a sort of pop hardcore."[20] "This fast and furious beauty may have been recorded in two days, but it soon had the labels knocking at DeLonge and co’s door," said Total Guitar in 2012.[15]

Track listing

All tracks are written by Mark Hoppus, Tom DeLonge, and Scott Raynor, except where noted.

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Carousel" | DeLonge | 2:54 |

| 2. | "TV" | Hoppus | 1:41 |

| 3. | "Strings" | Hoppus | 2:25 |

| 4. | "Fentoozler" | Hoppus | 2:06 |

| 5. | "Time" | Hoppus | 2:49 |

| 6. | "Romeo and Rebecca" | DeLonge | 2:34 |

| 7. | "21 Days" | DeLonge | 4:03 |

| 8. | "Sometimes" | Hoppus | 1:08 |

| 9. | "Degenerate" | DeLonge | 2:28 |

| 10. | "Point of View" | DeLonge | 1:11 |

| 11. | "My Pet Sally" | DeLonge | 1:36 |

| 12. | "Reebok Commercial" | Hoppus | 2:36 |

| 13. | "Toast and Bananas" | DeLonge | 2:33 |

| 14. | "The Family Next Door" (Hoppus, DeLonge, Raynor, Brian Casper[1]) | Hoppus/DeLonge | 1:47 |

| 15. | "Transvestite" | Hoppus/DeLonge | 3:59 |

| Total length: | 35:49 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Carousel" | DeLonge | 2:40 |

| 2. | "TV" | Hoppus | 1:37 |

| 3. | "Strings" | Hoppus | 2:28 |

| 4. | "Fentoozler" | Hoppus | 2:03 |

| 5. | "Time" | Hoppus | 2:46 |

| 6. | "Romeo and Rebecca" | DeLonge | 2:31 |

| 7. | "21 Days" | DeLonge | 4:01 |

| 8. | "Sometimes" | Hoppus | 1:04 |

| 9. | "Point of View" | DeLonge | 1:11 |

| 10. | "My Pet Sally" | DeLonge | 1:36 |

| 11. | "Reebok Commercial" | Hoppus | 2:35 |

| 12. | "Toast and Bananas" | DeLonge | 2:26 |

| 13. | "The Girl Next Door" (Ben Weasel) | Hoppus | 2:31 |

| 14. | "Don't" | Hoppus | 2:26 |

| Total length: | 31:55 | ||

Personnel

|

Production

Design

|

Chart positions

Weekly charts

See also

References

Notes

External links

|