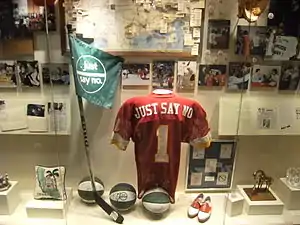

Just Say No

"Just Say No" was an advertising campaign prevalent during the 1980s and early 1990s as a part of the U.S. "War on Drugs", aiming to discourage children from engaging in illegal recreational drug use by offering various ways of saying no. The slogan was created and championed by First Lady Nancy Reagan during her husband's presidency.[1]

Initiation

The campaign emerged from a substance abuse prevention program supported by the National Institutes of Health, pioneered in the 1970s by University of Houston Social Psychology Professor Richard I. Evans. Evans promoted a social inoculation model, which included teaching student skills to resist peer pressure and other social influences. The campaign involved University projects done by students across the nation. Jordan Zimmerman, then a student at University of South Florida, and later an advertising entrepreneur,[2] won the campaign. The anti-drug movement was among the resistance skills recommended in response to low peer pressure, and Nancy Reagan's larger campaign proved to be a useful dissemination of this social inoculation strategy.[3]

Nancy Reagan first became involved during a campaign trip in 1980 to Daytop Village, New York. She recalls feeling impressed by a need to educate the youth about drugs and drug abuse.[1] Upon her husband's election to the presidency, she returned to Daytop Village and outlined how she wished to help educate the youth.[1] She stated in 1981 that her best role would be to bring awareness about the dangers of drug abuse:

Understanding what drugs can do to your children, understanding peer pressure and understanding why they turn to drugs is ... the first step in solving the problem.[1]

Efforts

The "Just Say No" slogan was the creation of Robert Cox and David Cantor, advertising executives at the New York office of Needham, Harper & Steers/USA in the early 1980s.[4]

In 1982, the phrase "Just Say No" first emerged when Nancy Reagan was visiting Longfellow Elementary School in Oakland, California.[5] When asked by a schoolgirl what to do if she was offered drugs by her peers, the First Lady responded, "Just say 'no'."[6] Just Say No club organizations within schools and school-run anti-drug programs soon became common, in which young people were making pacts not to experiment with drugs.[7]

When asked about her efforts in the campaign, Nancy Reagan said: "If you can save just one child, it's worth it."[8] She traveled throughout the United States and several other nations, totaling over 250,000 miles (400,000 km).[7] Nancy Reagan visited drug rehabilitation centers and abuse prevention programs; with the media attention that the first lady receives, she appeared on television talk shows, recorded public service announcements, and wrote guest articles.[7] By the autumn of 1985, she had appeared on 23 talk shows, co-hosted an October 1983 episode of Good Morning America,[9] and starred in a two-hour PBS documentary on drug abuse.[10]

The campaign and the phrase "Just Say No" made their way into popular American culture when television series such as Diff'rent Strokes and Punky Brewster produced episodes centered on the campaign. In 1983, Nancy Reagan appeared as herself in the television programs Dynasty and Diff'rent Strokes to garner support for the anti-drug campaign.[11] She participated in a 1985 rock music video "Stop the Madness" as well.[12] La Toya Jackson became spokesperson for the campaign in 1987 and recorded a song titled "Just Say No" with British hit producers Stock/Aitken/Waterman.[13]

In 1985, Nancy Reagan expanded the campaign internationally. She invited the First Ladies of 30 nations to the White House in Washington, DC, for a conference entitled the "First Ladies Conference on Drug Abuse".[7] She later became the first First Lady invited to address the United Nations.[7]

She enlisted the help of the Girl Scouts of the United States of America, Kiwanis Club International, and the National Federation of Parents for a Drug-Free Youth to promote the cause;[10] the Kiwanis put up over 2000 billboards with Nancy Reagan's likeness and the slogan.[10] Over 5000 Just Say No clubs were founded in schools and youth organizations in the United States and abroad.[10] Many clubs and organizations remain in operation around the country, where they aim to educate children and teenagers about the effects of drugs.[1]

Just Say No crossed over to the United Kingdom in the 1980s, where it was popularized by the BBC's 1986 "Drugwatch" campaign, which revolved around a heroin-addiction storyline in the popular children's TV drama serial Grange Hill. The cast's cover of the original US campaign song, with an added rap, reached the UK top ten.[14] The death of Anna Wood in Sydney, Australia and British teen Leah Betts from Essex in the mid-1990s sparked a media firestorm across both the UK and Australia over the use of illegal drugs. Wood's parents even released her school photograph on a badge with the saying "Just say no to drugs" placed on it to warn society on the dangers of illicit drug use. The photograph was widely circulated in the media. A photo of Betts in a coma in her hospital bed was also circulated in British media. Both teenagers died due to water intoxication as they drank too much water after ingesting ecstasy.[15][16]

Effects

Nancy Reagan's related efforts increased public awareness of drug use, but a direct relationship between reduced drug use and the Just Say No campaign cannot be established. Although the use and abuse of illegal recreational drugs significantly declined during the Reagan presidency,[17][18][19] this may be a spurious correlation: a 2009 analysis of 20 controlled studies on enrollment in one of the most popular "Just Say No" programs, DARE, showed no effect on drug use.[20]

The campaign did draw some criticism. Nancy Reagan's approach to promoting drug awareness was labeled simplistic by critics who argued that the solution was reduced to a catch phrase.[21] In fact, two studies suggested that enrollees in DARE-like programs were actually more likely to use alcohol and cigarettes.[20] Critics have also suggested that inflamed fears from "Just Say No" exacerbated mass incarceration and prevented youth from receiving accurate information about dealing with drug abuse.[22] Critics also think that "Just Say No" contributed towards the well seasoned stigma about people who use drugs being labelled as "bad", and the stigma toward those people who are addicted to drugs being labelled as making a cognizant immoral choice to engage in drug use.

References

- "Mrs. Reagan's Crusade". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on April 27, 2006.

- Zimmerman, Jordan (2015-01-25). Who Is Jordan Zimmerman? Blog, 25 January 2015. Retrieved from http://www.jzleadingfearlessly.com/who-is-jordan-zimmerman/.

- Evans, R.I. (in press). Just say no. In Breslow, L., Encyclopedia of Public Health (p. 1354). New York: Macmillan.

- Roberts, Sam (June 22, 2016). "Robert Cox, Man Behind the 'Just Say No' Antidrug Campaign, Dies at 78". The New York Times.

- Loizeau, Pierre-Marie (1984). Nancy Reagan: The Woman Behind the Man. Nova Publishers. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-1-59033-759-2.

- "Remarks at the Nancy Reagan Drug Abuse Center Benefit Dinner in Los Angeles, California". Ronald Reagan Foundation. January 4, 1989. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

... in Oakland where a schoolchild in an audience Nancy was addressing stood up and asked what she and her friends should say when someone offered them drugs. And Nancy said, "Just say no." And within a few months thousands of Just Say No clubs had sprung up in schools around the country.

- "First Lady Biography: Nancy Reagan". National First Ladies Library. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- Tribute to Nancy Reagan (Motion picture). Motion Picture Association, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. May 2005. Event occurs at 3:08. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- "First Lady, Press Office: Records, 1981–1989". Reagan Library – via utexas.edu.

- Benze, James G. (2005), p. 62

- "'Diff'rent Strokes': The Reporter (1983)". imdb.com. The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- Brian L. Dyak (Executive Producer), William N. Utz (Executive Producer) (December 11, 1985). Stop the Madness (Music Video). Hollywood, California and The White House, Washington, DC: E.I.C. Event occurs at 3:15.

- Stewart, Tessa (March 7, 2016). "Pop-Culture Legacy of Nancy Reagan's Just Say No Campaign". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- Malvern, Jack (December 12, 2003). "Just say no". The Daily Summit. British Council.

- Mullany, Ashlee (November 9, 2014). "Anna Wood's father in despair as another teenager dies". Daily Telegraph Australia. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- Buchanan, Daisy (November 16, 2015). "Leah Betts died 20 years ago and we still can't be honest about drugs". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- Benze, James G. (2005), p. 63

- "NIDA InfoFacts: High School and Youth Trends". National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- "Interview: Dr. Herbert Kleber". Frontline. PBS. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

The politics of the Reagan years and the Bush years probably made it somewhat harder to get treatment expanded, but at the same time, it may have decreased initiation and use. For example, marijuana went from thirty-three percent of high-school seniors in 1980 to twelve percent in 1991.

- Lilienfeld, Scott O.; Arkowitz, Hal (January 1, 2014). "Why 'Just Say No' Doesn't Work". Scientific American.

- Wolf, Julie. "Nancy Reagan". American Experience. PBS. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- McGrath, Michael (March 8, 2016). "Nancy Reagan and the negative impact of the 'Just Say No' anti-drug campaign". The Guardian.

- Benze, James G. Jr. (2005). Nancy Reagan: On the White House Stage. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1401-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Just Say No. |

- First Lady Nancy Reagan and Just Say No at the Reagan Presidential Library

- First Lady Nancy Reagan throws out the first pitch at the 1988 World Series for Just Say No at youTube