Càrn Eige

Càrn Eige, sometimes spelt Càrn Eighe, is a mountain in the north of Scotland. At an elevation of 1,183 metres (3,881 ft) above sea level, it is the highest mountain in northern Scotland (north of the Great Glen), the twelfth-highest summit above sea level in the British Isles, and, in terms of relative height (topographic prominence), it is the second-tallest mountain in the British Isles after Ben Nevis (its "parent peak" for determination of topographic prominence).[2] The highpoint of the historic county of Ross and Cromarty, it is the twin summit of the massif, being mirrored by the 1,181-metre (3,875 ft) Mam Sodhail, to the south on the same ridge.

| Càrn Eige | |

|---|---|

Càrn Eige seen from the large cairn on Mam Sodhail. | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,183 m (3,881 ft) [1] |

| Prominence | c. 1148 m Ranked 2nd in British Isles |

| Parent peak | Ben Nevis |

| Listing | Marilyn, Munro, Hardy, County top (Ross and Cromarty) |

| Naming | |

| English translation | File hill or Notch hill |

| Language of name | Gaelic |

| Pronunciation | Scottish Gaelic: [ˈkʰaːrˠn̪ˠ ˈekʲə] English approximation: karn-EK-yə |

| Geography | |

| Location | Glen Affric, Scotland |

| OS grid | NH123262 |

| Topo map | OS Landranger 25 |

Administratively, it is in the Highland council area, on the boundary between the historic counties of Inverness and Ross and Cromarty, on the former lands of the Clan Chisholm. The mountain is difficult to access, being 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from the nearest road, and its sub-peak to the north is even more inaccessible.

Etymology

The name "Càrn Eige" comes from the Scottish Gaelic language, and probably means either File Hill or Notch Hill. An alternative translation, if it were to be called "Càrn Eigh", would be the Hill of Ice; this would make it the only Scottish mountain with the word "ice" in its name.[3]

Geography

Topography

The summit is pyramid-shaped, the culmination of three ridges meeting in an equilateral configuration. The nearest Munro is its "twin summit", Mam Sodhail, about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) to the southwest,[4] and there are three other Munros on the massif. Beinn Fhionnlaidh ends a spur to the north, and there is a much longer grassy ridge running out to the east, which after 4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi) leads to Tom a' Choinich (1,112 metres (3,648 ft)) and then after a similar distance culminates in the rather bland summit of Toll Creagach, at 1,054 metres (3,458 ft).[5] As well as the five Munros topping the massif, there are a further 10 subsidiary minor summits, known as "Munro Tops".[6]

This ridge lies roughly equidistant between two lochs, Loch Affric/Loch Beinn a' Mheadhoin to the south, and the larger Loch Mullardoch to the north.[4] Opposing several lower summits across Loch Mullardoch, the highest being Sgurr na Lapaich at 1,150 metres (3,770 ft), it dominates the area, being the highest summit in the region. To the north of the summit, there is an impressive glacial corrie that falls half a kilometre to the shores of Corrie Lochan.[7]

Geology

Càrn Eige lies in the north-west highlands, north of the Great Glen Fault. Discontinuous sheets of West Highland granite gneiss stretch up from this fault through Glen Affric.[8]

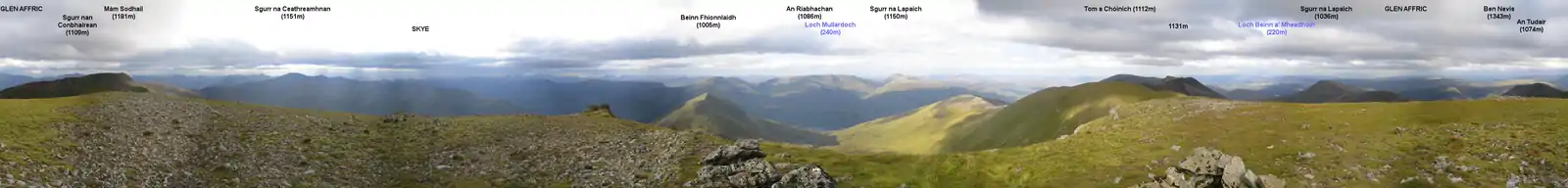

Summit panorama

History

In 1848, the mountain was climbed by Colonel Winzer of the Ordnance Survey, who discovered a pile of stones and deduced that it had been climbed earlier, although a local gamekeeper suggested it was a shelter (bothy) for watchers.[9] In 1891 Sir Hugh Munro, 4th Baronet listed Càrn Eige in his Munro Tables, in which it has remained.[10] The full set of Munros has been "completed" at least 5,000 times since then.

Flora and fauna

Typical of the Scottish Highlands, the slopes of the mountain are largely treeless, especially at higher altitudes. The mountain is instead clad in a variety of grasses and mosses, which towards the summit are covered by snow during parts of the year. The lower slopes are described by Muir as "boggy, sodden moorland".[11] The base of the southern side of the mountain, adjacent to Loch Affric, is wooded with Scots pine interspersed with other species such as oak, birch, and beech.[12] These woods are inhabited by a number of endemic fauna, including the crested tit and the Scottish crossbill.[13]

Location

Situated in the north of Scotland, Càrn Eige is on the border of two historic counties, Inverness and Ross and Cromarty, and is the highest point of the latter.[7] The mountain is very remote, more than 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from the nearest road, in Glen Affric,[5] although there is a youth hostel (Alltbeithe)[14] in the same valley that is nearer. The summit is at UK grid reference NH123261,[15] which falls on the OS Landranger 25 map, the OS Explorer series 414–5, and the much larger area map 9.[16]

Ascents

The mountain can be ascended from the south, beginning at Loch Affric, up the north side of Gleann nam Fiadh (fording a stream) and reaching the summit of both Càrn Eige itself[17] and then Mam Sodhail in either clockwise or anticlockwise fashion (route described anticlockwise), potentially including Beinn Fhionnlaidh as an extra, since this is relatively difficult to access in any other way.[4][18] The summit is marked by an Ordnance Survey triangulation pillar (trig point) and a cairn. Including only the three principal Munros (i.e. excluding the two summits to the east), a successful ascent of this mountain might take between 9 and 10 hours.[16] There is also a route to the summit from the north, via Beinn Fhionnlaidh, starting from a boat-accessible spot on Loch Mullardoch.[19]

References

Footnotes

- "walkhighlands Carn Eige". walkhighlands.co.uk. 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- Dawson 1992.

- Drummond & Stewart 1991, p. 13.

- "Carn Eige". Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "Glen Affric". Scotland Mountain Guide. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- Kew 2012, p. 163.

- Muir 2011, p. 175.

- Harris & Gibbons 1994, p. 23.

- Townsend 2010, p. 368.

- "1891 Munro Map". Mountains of Scotland. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- Muir 2011, p. 177.

- Uney 2009, p. 177.

- Uney 2009, p. 182.

- Bennet & Strang 1990, p. 131.

- Kew 2012, p. 164.

- Kew 2012, p. 161.

- Bennet & Strang 1990, p. 138.

- Muir 2011, p. 176–7.

- Bailey 2012, p. 102.

Bibliography

- Bailey, Dan (2012). Great Mountain Days in Scotland: 50 Classic Hillwalking Challenges. Cicerone Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-85284-612-1.

- Bennet, Donald John; Strang, Tom (1 July 1990). The Northwest Highlands. Scottish Mountaineering Trust. ISBN 978-0-907521-28-0.

- Dawson, Alan (1 January 1992). The Relative Hills of Britain. Cicerone Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-84965-206-3.

- Butterfield, Irvine (1993). The high mountains of Britain and Ireland: a guide for mountain walkers. Diadem Books. ISBN 978-0-906371-30-5.

- Drummond, Peter; Stewart, Donald William (31 May 1991). Scottish Hill and Mountain Names: The Origin and Meaning of the Names of Scotland's Hills and Mountains. Scottish Mountaineering Trust. ISBN 978-0-907521-30-3.

- Harris, Anthony Leonard; Gibbons, Wes (1994). A Revised Correlation of Precambrian Rocks in the British Isles. Geological Society of London. ISBN 978-1-897799-11-6.

- Kew, Steve (2 March 2012). Walking the Munros Vol 2 - Northern Highlands and the Cairngorms. Cicerone Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-84965-483-8.

- Muir, Jonny (5 October 2011). The UK's County Tops: Reaching the top of 91 historic counties. Cicerone Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-84965-553-8.

- Townsend, Chris (2010). Scotland. Cicerone Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-85284-442-4.

- Uney, Graham (May 2009). Backpacker's Britain: Northern Scotland: Thirty Two- and Three-day Treks. Cicerone Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-85284-458-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carn Eige. |

- Càrn Eige is at coordinates 57.288438°N 5.114053°W

- Computer-generated virtual panoramas Càrn EigeIndex

- Càrn Eighe on Scottish Sport

- Càrn Eighe on Munro Magic