CSS Arkansas

CSS Arkansas was an ironclad ram of the Confederate States Navy named after the State of Arkansas. Arkansas is most noted for her actions in the Western Theater, when she steamed through a United States Navy fleet at Vicksburg on 15 July 1862 during the American Civil War. She was set on fire and destroyed by her crew after her engines broke down on 6 August. Her remains lie under a levee near Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

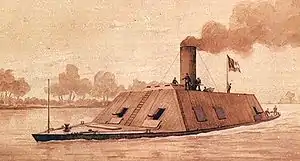

The C. S. S. Arkansas by R. G. Skerrett | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Arkansas |

| Namesake: | State of Arkansas |

| Ordered: | 24 August 1861 |

| Builder: | John T. Shirley, Memphis, Tennessee |

| Cost: | CS$76,920 |

| Laid down: | October 1861 |

| Launched: | 24 April 1862 |

| Fate: | Destroyed by her crew, 6 August 1862 |

| General characteristics (1862) | |

| Class and type: | Arkansas-class ironclad |

| Displacement: | approximately 800 tons |

| Length: | 165 ft (50 m) |

| Beam: | 35 ft (11 m) |

| Draft: | 11.6 ft (3.5 m) |

| Speed: | 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) |

| Complement: | 232 officers and men |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | Casemate: railroad iron over wood and compressed cotton. Pilothouse: 2 in (51 mm). Top: 1 in (25 mm). Stern: boiler iron only |

History

Construction

Her keel was laid down at Memphis, Tennessee, by John T. Shirley in October 1861.[1] In April 1862, Arkansas was moved to Greenwood, Mississippi, on the Yazoo River, to prevent her capture when Memphis fell to the Union Navy. Her sister ship, CSS Tennessee, was burned on the stocks because she was not near enough to completion to be launched.[2]

In May 1862 Capt. Isaac N. Brown of the Confederate States Navy received orders at Vicksburg from the Navy Department in Richmond, to proceed to Greenwood, and there assume command of Arkansas. His orders were to finish and equip the vessel. When Captain Brown arrived, he found a mere hull, without armor, engines in pieces, and guns without carriages. Supplies of railroad iron, intended as armor for the ship, were lying at the bottom of the river. A recovery mission was ordered, and the armor was pulled up out of the mud. Captain Brown then had Arkansas towed to Yazoo City, Mississippi, where he pressed into service local craftsmen, and also got the assistance of 200 soldiers from the Confederate army as construction crews.[3] After five strenuous weeks of labor under the hot summer sun, the ship had to leave due to falling river levels. She had been fully outfitted, except for the curved armor intended to surround her stern and pilot house. Boiler plate was stuck on these areas "for appearances' sake."

Breaking through to Vicksburg

During this time, the Federal Navy had attacked Vicksburg with a large force made up of a squadron of ships, under Flag Officer David G. Farragut, that had come up from the Gulf of Mexico and a flotilla of United States Army gunboats and rams, under Flag Officer Charles H. Davis, from upriver.

Soon thereafter, General Earl Van Dorn, commanding the Confederate Army forces at Vicksburg, and as such in control of Arkansas, ordered Captain Brown to bring his ship down to the city. Brown filled out the crew of Arkansas with more than 100 sailors from vessels on the Mississippi, plus about 60 Missouri soldiers. Capt. William Pratt Parks was chosen to command the gun on the port side. Brown stated, "The only trouble they ever gave me was to keep them from running Arkansas into the Union fleet before we were ready for battle." He then set sail for Vicksburg and the Union fleet.

Capt. Parks had enlisted in Woodruff's Battery, Arkansas Light Artillery. Transferred east, Parks was elected First Lieut. in Co. H (Hoadley's Arkansas Battery), 1st Tennessee Heavy Artillery Regiment. Co. H. was transferred from Fort Pillow to Vicksburg and became part of new Co. B (composed of Hoadley's (old) Co. H, along with (old) Cos. A and G and part of (old) Co. C. Parks was selected to serve as Capt. of Co. B while serving aboard Arkansas as commander of the larboard gun. Parks would later sink USS Cincinnati while in command of Co. B. as part of the Upper Water Battery defense of Vicksburg.

After approximately 15 miles (24 km), it was discovered that steam from the boilers had leaked into the forward magazine and rendered the gunpowder wet and useless. Captain Brown and his men found a clearing along the bank of the Yazoo River, landed the wet powder and spread it out on tarpaulins in the sun to dry. With constant stirring and shaking the powder was dry enough to ignite by sundown. Arkansas proceeded on her way.[4]

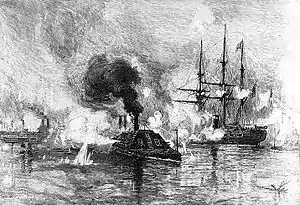

Shortly after sunrise on 15 July 1862, three Federal vessels were sighted steaming towards Arkansas—the ironclad Carondelet, the wooden gunboat Tyler, and the ram Queen of the West. The Federal vessels turned downriver, and a running battle ensued. Carondelet was quickly disabled with a shot through her steering mechanism, causing her to run aground. Attention was turned to Tyler and the ram, which ran for their fleet with Arkansas pursuing. Soon the Federal fleet came into view around the river bend above Vicksburg, "a forest of masts and smokestacks." Captain Brown determined to steam as close to the enemy vessels as possible in order to prevent his vessel being rammed and to sow confusion. The Federal ships were largely immobile, as they did not have their steam up. They and Arkansas exchanged shots at close range, but she soon passed to safety beyond them. Arkansas arrived at Vicksburg to the sound of enthusiastic cheering from the citizens and within sight of the lower Federal fleet.[5]

That night, Farragut's fleet ran past the batteries at Vicksburg and attempted to destroy Arkansas while doing so. They did not move until so late in the day, however, that they could not see their target. Only one shell hit home, killing two men and wounding three.[6]

Although Arkansas did not destroy any enemy vessels, she inflicted losses among the personnel of the Federal fleets. In the engagement on the Yazoo and her passage of the fleet at Vicksburg, their total loss was 18 killed, 50 wounded, and an additional 10 missing (probably drowned).[7] Farragut's fleet lost another 5 killed and 9 wounded when they ran past the Vicksburg batteries.[8] The cost to Arkansas for the entire day's action was 12 killed and 18 wounded.[9]

Under the Vicksburg bluffs

After repairs, Arkansas again appeared to threaten her enemies, forcing them to keep up steam 24 hours a day in the hottest part of the summer. To remove the problem, the Union fleet tried once again to destroy the ironclad at her mooring. At this time, the severely reduced crew of Arkansas could man only three guns, so she depended for protection on the shore batteries. On the morning of 22 July, USS Essex, Queen of the West, and Sumter mounted an ill-coordinated attack. First Essex attempted to ram, but as she approached, the Arkansas crew were able to spring her. As a result, Essex missed her target and ran aground instead, where for ten minutes she remained under fire from both Arkansas and the shore batteries. The armor on Essex protected her crew, however, so she lost only one man killed and three wounded. On the other hand, one of her shots penetrated the iron plating on Arkansas, killing six and wounding six. When Essex worked off the bank, she continued downstream, where she joined Farragut's squadron.

Meanwhile, Queen of the West was making her run. Her captain misjudged her speed, so she ran past Arkansas and had to come back and ram upstream. Although she struck fairly, her reduced momentum meant that the collision did little damage. She then returned to the flotilla above the city. She had been riddled by shot from the batteries, but surprisingly suffered no serious casualties.

Farragut had already been pressing the Navy Department for permission to leave Vicksburg. It was clear that he would need assistance from the Army to capture the city, assistance that was not forthcoming. Sickness among his sailors, unacclimatised to the heat of summer in Mississippi, reduced their fighting strength by as much as a third. Furthermore, the annual drop in the level of the river threatened to strand his deep-draft ships. The constant vigilance now necessitated by the presence of Arkansas finally tipped the balance. He got permission to return to the vicinity of New Orleans, and on 24 July his fleet left.[10] With nothing his flotilla could do, Davis also withdrew. He took his vessels back to Helena, where he could still watch the river north of Vicksburg.

Final fight at Baton Rouge

With the Federal fleet gone, Captain Brown requested and was granted four days of leave, which he took in Grenada. Before leaving, he pointed out to General Van Dorn that the engines of his ship needed repairs before she could be used. He also gave positive orders to his executive officer, Lieut. Henry K. Stevens, not to move her until he returned. Unfortunately for the ship, Van Dorn disregarded his subordinate. He ordered Lieut. Stevens to take Arkansas down to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where she would support an attack on the Union position there by a Confederate army force led by General John C. Breckinridge. Stevens demurred, citing his orders from Brown, and referred the question to "a senior officer of the Confederate navy." The "senior officer" chose not to intervene. Stevens, now under the orders of two superior officers, had to rush the ship down the river.[11]

Confirming Brown's fears, the engines broke down several times between Vicksburg and Baton Rouge. Each time, the engineer was able to get them running again, but it was clear that they were unreliable. Nevertheless, the ship was able to get all the way to Baton Rouge, where she prepared for battle with a small Federal flotilla that included her old opponent USS Essex. On the morning of 6 August, Essex came in sight, and Arkansas moved into the stream to meet her. Just at this time, crank pins on both engines failed almost simultaneously, and Arkansas drifted helplessly to the shore.

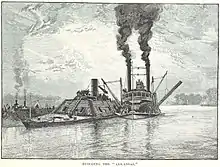

Stevens prepared to abandon ship. He ordered the engines to be broken up, the guns to be loaded and excess shells spread around, and then the ship set afire. The crew then left. About this time, the ship broke free and began to drift down the river, and Stevens, the last man to leave, had to swim ashore. The burning vessel drifted down among the attacking Federal fleet, which watched from a respectful distance. At about noon, Arkansas blew up.[12]

Wreck

The wreck of the Arkansas rests deep under the levee on a north/south heading about 1.4 miles (2.3 km) south from the auto/railroad bridge at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 230 yards (210 m) below Mile 233.[13]

References

- Abbreviations used in these notes:

- ORN I (Official records, Navies, series I): Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion

- Still, Iron afloat, p. 62.

- Soley, James Russell, "The Union and Confederate Navies," Battles and Leaders, v. 1, p. 629.

- Still, Iron afloat, p. 65.

- Brown, Isaac N., "The Confederate gun-boat Arkansas", Battles and leaders,, v. 3, pp. 572–573.

- Brown, Isaac N., "The Confederate gun-boat Arkansas", Battles and Leaders, pp. 575–576.

- Still, Iron Afloat, p. 72.

- ORN I, v. 19, pp. 4, 7.

- ORN I, v. 19, p. 8.

- ORN I, v. 19, p. 69. The list of wounded is obviously incomplete; Brown himself is not listed, although he is known to have suffered a head wound.

- Still, Iron afloat, pp. 74–75.

- The "senior officer" was Flag Officer William F. Lynch. Brown did not forgive Lynch for his witless acquiescence to Van Dorn, and pointedly refused even to name him when he wrote his memoir years later. Brown, Isaac N., "The Confederate gun-boat Arkansas", Battles and Leaders, v. 3, p. 579.

- Still, Iron Afloat, pp. 76–78. The motions of Arkansas just before the final breakdown of her engines are not clear. See Still's note on page 77.

- "Search for the Ironclads: The Expedition to Find the Confederate Ironclads Manassas, Louisiana, and Arkansas".

Sources

- Bisbee, Saxon T. (2018). Engines of Rebellion: Confederate Ironclads and Steam Engineering in the American Civil War. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-81731-986-1.

- Johnson, Robert Underwood (1888). Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. III. New York: The Century Company.

- Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I: 27 volumes. Series II: 3 volumes. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894–1922. See particularly Series I, volume 19, pp. 3–75.

- "Search for the Ironclads: The Expedition to Find the Confederate Ironclads Manassas, Louisiana, and Arkansas". National Underwater and Marine Agency. November 1981. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Still, William N., Jr. (1985). Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Armorclads (Reprint of the 1971 ed.). Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-454-3.

Further reading

- Davis, William C., ed. (1990). Diary of a Confederate Soldier: John S. Jackman of the Orphan Brigade. American Military History. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 43, 49, 51–52. ISBN 0-87249-695-3. LCCN 90012431. OCLC 906557161.

- Parker, William Harwar (1899). "Chapter VIII: The Ram Arkansas – Her Completion on the Yazoo River – Her Daring Dash Through the Federal Fleet". In Evans, Clement A. (ed.). The Confederate States Navy. Confederate Military History. XII. Atlanta, Ga.: Confederate Publishing Company. pp. 63–66 – via Internet Archive.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (2006). Civil War Navies 1855–1883. The U.S. Navy Warship Series. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97870-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to CSS Arkansas. |

- CSS Arkansas at Encyclopedia of Arkansas

- CSS Arkansas (Vicksburg, Mississippi) at The Historical Marker Database (HMdb.org)

- CSS Arkansas (Yazoo City, Mississippi) at The Historical Marker Database (HMdb.org)

- Missourians or Volunteers From Missouri Units on the CSS Arkansas at Internet Archive