Carbon steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05% up to 3.8% by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

- no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, cobalt, molybdenum, nickel, niobium, titanium, tungsten, vanadium, zirconium, or any other element to be added to obtain a desired alloying effect;

- the specified minimum for copper does not exceed 0.860%;

- or the maximum content specified for any of the following elements does not exceed the percentages noted: manganese 1.65%; silicon 0.60%; copper 0.60%.[1]

| Steels |

|---|

|

| Phases |

| Microstructures |

| Classes |

| Other iron-based materials |

The term carbon steel may also be used in reference to steel which is not stainless steel; in this use carbon steel may include alloy steels. High carbon steel has many different uses such as milling machines, cutting tools (such as chisels) and high strength wires. These applications require a much finer microstructure, which improves the toughness.

As the carbon percentage content rises, steel has the ability to become harder and stronger through heat treating; however, it becomes less ductile. Regardless of the heat treatment, a higher carbon content reduces weldability. In carbon steels, the higher carbon content lowers the melting point.[2]

Type

Mild or low-carbon steel

Mild steel (iron containing a small percentage of carbon, strong and tough but not readily tempered), also known as plain-carbon steel and low-carbon steel, is now the most common form of steel because its price is relatively low while it provides material properties that are acceptable for many applications. Mild steel contains approximately 0.05–0.30% carbon[1] making it malleable and ductile. Mild steel has a relatively low tensile strength, but it is cheap and easy to form; surface hardness can be increased through carburizing.[3]

In applications where large cross-sections are used to minimize deflection, failure by yield is not a risk so low-carbon steels are the best choice, for example as structural steel. The density of mild steel is approximately 7.85 g/cm3 (7850 kg/m3 or 0.284 lb/in3)[4] and the Young's modulus is 200 GPa (29,000 ksi).[5]

Low-carbon steels display yield-point runout where the material has two yield points. The first yield point (or upper yield point) is higher than the second and the yield drops dramatically after the upper yield point. If a low-carbon steel is only stressed to some point between the upper and lower yield point then the surface develops Lüder bands.[6] Low-carbon steels contain less carbon than other steels and are easier to cold-form, making them easier to handle.[7] Typical applications of low carbon steel are car parts, pipes, construction, and food cans.[8]

High-tensile steel

High-tensile steels are low-carbon, or steels at the lower end of the medium-carbon range, which have additional alloying ingredients in order to increase their strength, wear properties or specifically tensile strength. These alloying ingredients include chromium, molybdenum, silicon, manganese, nickel and vanadium. Impurities such as phosphorus or sulphur have their maximum allowable content restricted.

- 41xx steel

- 4140 steel

- 4145 steel

- 4340 steel

- 300M steel

- EN25 steel – 2.521% nickel-chromium-molybdenum steel

- EN26 steel

Higher-carbon steels

Carbon steels which can successfully undergo heat-treatment have a carbon content in the range of 0.30–1.70% by weight. Trace impurities of various other elements can have a significant effect on the quality of the resulting steel. Trace amounts of sulfur in particular make the steel red-short, that is, brittle and crumbly at working temperatures. Low-alloy carbon steel, such as A36 grade, contains about 0.05% sulphur and melts around 1,426–1,538 °C (2,599–2,800 °F).[9] Manganese is often added to improve the hardenability of low-carbon steels. These additions turn the material into a low-alloy steel by some definitions, but AISI's definition of carbon steel allows up to 1.65% manganese by weight.

AISI classification

Carbon steel is broken down into four classes based on carbon content:[1]

Low-carbon steel

0.05 to 0.25% carbon (plain carbon steel) content.[1]

Medium-carbon steel

Approximately 0.3–0.5% carbon content.[1] Balances ductility and strength and has good wear resistance; used for large parts, forging and automotive components.[10][11]

High-carbon steel

Approximately 0.6 to 1.0% carbon content.[1] Very strong, used for springs, edged tools, and high-strength wires.[12]

Ultra-high-carbon steel

Approximately 1.25–2.0% carbon content.[1] Steels that can be tempered to great hardness. Used for special purposes like (non-industrial-purpose) knives, axles or punches. Most steels with more than 2.5% carbon content are made using powder metallurgy.

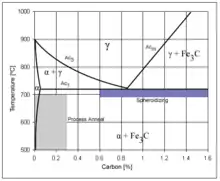

Heat treatment

The purpose of heat treating carbon steel is to change the mechanical properties of steel, usually ductility, hardness, yield strength, or impact resistance. Note that the electrical and thermal conductivity are only slightly altered. As with most strengthening techniques for steel, Young's modulus (elasticity) is unaffected. All treatments of steel trade ductility for increased strength and vice versa. Iron has a higher solubility for carbon in the austenite phase; therefore all heat treatments, except spheroidizing and process annealing, start by heating the steel to a temperature at which the austenitic phase can exist. The steel is then quenched (heat drawn out) at a moderate to low rate allowing carbon to diffuse out of the austenite forming iron-carbide (cementite) and leaving ferrite, or at a high rate, trapping the carbon within the iron thus forming martensite. The rate at which the steel is cooled through the eutectoid temperature (about 727 °C) affects the rate at which carbon diffuses out of austenite and forms cementite. Generally speaking, cooling swiftly will leave iron carbide finely dispersed and produce a fine grained pearlite and cooling slowly will give a coarser pearlite. Cooling a hypoeutectoid steel (less than 0.77 wt% C) results in a lamellar-pearlitic structure of iron carbide layers with α-ferrite (nearly pure iron) between. If it is hypereutectoid steel (more than 0.77 wt% C) then the structure is full pearlite with small grains (larger than the pearlite lamella) of cementite formed on the grain boundaries. A eutectoid steel (0.77% carbon) will have a pearlite structure throughout the grains with no cementite at the boundaries. The relative amounts of constituents are found using the lever rule. The following is a list of the types of heat treatments possible:

- Spheroidizing

- Spheroidite forms when carbon steel is heated to approximately 700 °C for over 30 hours. Spheroidite can form at lower temperatures but the time needed drastically increases, as this is a diffusion-controlled process. The result is a structure of rods or spheres of cementite within primary structure (ferrite or pearlite, depending on which side of the eutectoid you are on). The purpose is to soften higher carbon steels and allow more formability. This is the softest and most ductile form of steel.[13]

- Full annealing

- Carbon steel is heated to approximately 40 °C above Ac3‹See Tfd›? or Acm‹See Tfd›? for 1 hour; this ensures all the ferrite transforms into austenite (although cementite might still exist if the carbon content is greater than the eutectoid). The steel must then be cooled slowly, in the realm of 20 °C (36 °F) per hour. Usually it is just furnace cooled, where the furnace is turned off with the steel still inside. This results in a coarse pearlitic structure, which means the "bands" of pearlite are thick.[14] Fully annealed steel is soft and ductile, with no internal stresses, which is often necessary for cost-effective forming. Only spheroidized steel is softer and more ductile.[15]

- Process annealing

- A process used to relieve stress in a cold-worked carbon steel with less than 0.3% C. The steel is usually heated to 550–650 °C for 1 hour, but sometimes temperatures as high as 700 °C. The image rightward shows the area where process annealing occurs.

- Isothermal annealing

- It is a process in which hypoeutectoid steel is heated above the upper critical temperature. This temperature is maintained for a time and then reduced to below the lower critical temperature and is again maintained. It is then cooled to room temperature. This method eliminates any temperature gradient.

- Normalizing

- Carbon steel is heated to approximately 55 °C above Ac3 or Acm for 1 hour; this ensures the steel completely transforms to austenite. The steel is then air-cooled, which is a cooling rate of approximately 38 °C (100 °F) per minute. This results in a fine pearlitic structure, and a more-uniform structure. Normalized steel has a higher strength than annealed steel; it has a relatively high strength and hardness.[16]

- Quenching

- Carbon steel with at least 0.4 wt% C is heated to normalizing temperatures and then rapidly cooled (quenched) in water, brine, or oil to the critical temperature. The critical temperature is dependent on the carbon content, but as a general rule is lower as the carbon content increases. This results in a martensitic structure; a form of steel that possesses a super-saturated carbon content in a deformed body-centered cubic (BCC) crystalline structure, properly termed body-centered tetragonal (BCT), with much internal stress. Thus quenched steel is extremely hard but brittle, usually too brittle for practical purposes. These internal stresses may cause stress cracks on the surface. Quenched steel is approximately three times harder (four with more carbon) than normalized steel.[17]

- Martempering (marquenching)

- Martempering is not actually a tempering procedure, hence the term marquenching. It is a form of isothermal heat treatment applied after an initial quench, typically in a molten salt bath, at a temperature just above the "martensite start temperature". At this temperature, residual stresses within the material are relieved and some bainite may be formed from the retained austenite which did not have time to transform into anything else. In industry, this is a process used to control the ductility and hardness of a material. With longer marquenching, the ductility increases with a minimal loss in strength; the steel is held in this solution until the inner and outer temperatures of the part equalize. Then the steel is cooled at a moderate speed to keep the temperature gradient minimal. Not only does this process reduce internal stresses and stress cracks, but it also increases the impact resistance.[18]

- Tempering

- This is the most common heat treatment encountered, because the final properties can be precisely determined by the temperature and time of the tempering. Tempering involves reheating quenched steel to a temperature below the eutectoid temperature then cooling. The elevated temperature allows very small amounts of spheroidite to form, which restores ductility, but reduces hardness. Actual temperatures and times are carefully chosen for each composition.[19]

- Austempering

- The austempering process is the same as martempering, except the quench is interrupted and the steel is held in the molten salt bath at temperatures between 205 °C and 540 °C, and then cooled at a moderate rate. The resulting steel, called bainite, produces an acicular microstructure in the steel that has great strength (but less than martensite), greater ductility, higher impact resistance, and less distortion than martensite steel. The disadvantage of austempering is it can be used only on a few steels, and it requires a special salt bath.[20]

Case hardening

Case hardening processes harden only the exterior of the steel part, creating a hard, wear resistant skin (the "case") but preserving a tough and ductile interior. Carbon steels are not very hardenable meaning they can not be hardened throughout thick sections. Alloy steels have a better hardenability, so they can be through-hardened and do not require case hardening. This property of carbon steel can be beneficial, because it gives the surface good wear characteristics but leaves the core flexible and shock-absorbing.

Forging temperature of steel

| Steel type | Maximum forging temperature | Burning temperature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°F) | (°C) | (°F) | (°C) | |

| 1.5% carbon | 1920 | 1049 | 2080 | 1140 |

| 1.1% carbon | 1980 | 1082 | 2140 | 1171 |

| 0.9% carbon | 2050 | 1121 | 2230 | 1221 |

| 0.5% carbon | 2280 | 1249 | 2460 | 1349 |

| 0.2% carbon | 2410 | 1321 | 2680 | 1471 |

| 3.0% nickel steel | 2280 | 1249 | 2500 | 1371 |

| 3.0% nickel–chromium steel | 2280 | 1249 | 2500 | 1371 |

| 5.0% nickel (case-hardening) steel | 2320 | 1271 | 2640 | 1449 |

| Chromium-vanadium steel | 2280 | 1249 | 2460 | 1349 |

| High-speed steel | 2370 | 1299 | 2520 | 1385 |

| Stainless steel | 2340 | 1282 | 2520 | 1385 |

| Austenitic chromium–nickel steel | 2370 | 1299 | 2590 | 1420 |

| Silico-manganese spring steel | 2280 | 1249 | 2460 | 1350 |

See also

- Cold working

- Hot working

- Welding

- Forging

- Aermet (High strength steels.)

- Maraging steel (Precipitation-hardened high-strength steels.)

- Eglin steel (A low-cost precipitation-hardened high-strength steel.)

References

- "Classification of Carbon and Low-Alloy Steels"

- Knowles, Peter Reginald (1987), Design of structural steelwork (2nd ed.), Taylor & Francis, p. 1, ISBN 978-0-903384-59-9.

- Engineering fundamentals page on low-carbon steel

- Elert, Glenn, Density of Steel, retrieved 23 April 2009.

- Modulus of Elasticity, Strength Properties of Metals – Iron and Steel, retrieved 23 April 2009.

- Degarmo, p. 377.

- "Low-carbon steels". efunda. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "What Are the Different Types of Steel? | Metal Exponents Blog". Metal Exponents. 18 August 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Ameristeel article on carbon steel Archived 18 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Nishimura, Naoya; Murase, Katsuhiko; Ito, Toshihiro; Watanabe, Takeru; Nowak, Roman (2012). "Ultrasonic detection of spall damage induced by low-velocity repeated impact". Central European Journal of Engineering. 2 (4): 650–655. Bibcode:2012CEJE....2..650N. doi:10.2478/s13531-012-0013-5.

- Engineering fundamentals page on medium-carbon steel

- Engineering fundamentals page on high-carbon steel

- Smith, p. 388

- Alvarenga HD, Van de Putte T, Van Steenberge N, Sietsma J, Terryn H (October 2014). "Influence of Carbide Morphology and Microstructure on the Kinetics of Superficial Decarburization of C-Mn Steels". Metall Mater Trans A. 46: 123–133. Bibcode:2015MMTA...46..123A. doi:10.1007/s11661-014-2600-y.

- Smith, p. 386

- Smith, pp. 386–387

- Smith, pp. 373–377

- Smith, pp. 389–390

- Smith, pp. 387–388

- Smith, p. 391

- Brady, George S.; Clauser, Henry R.; Vaccari A., John (1997). Materials Handbook (14th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-007084-9.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carbon steel. |

- Degarmo, E. Paul; Black, J T.; Kohser, Ronald A. (2003), Materials and Processes in Manufacturing (9th ed.), Wiley, ISBN 0-471-65653-4.

- Oberg, E.; et al. (1996), Machinery's Handbook (25th ed.), Industrial Press Inc, ISBN 0-8311-2599-3.

- Smith, William F.; Hashemi, Javad (2006), Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering (4th ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-295358-6.