Carmen

Carmen (French: [kaʁ.mɛn]) is an opera in four acts by French composer Georges Bizet. The libretto was written by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, based on a novella of the same title by Prosper Mérimée. The opera was first performed by the Opéra-Comique in Paris on 3 March 1875, where its breaking of conventions shocked and scandalized its first audiences.

| Carmen | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Georges Bizet | |

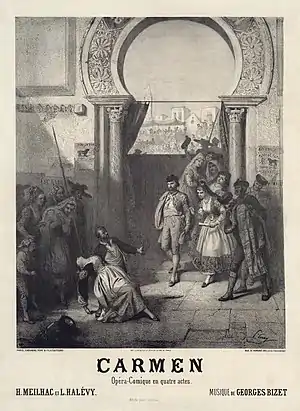

Poster by Prudent-Louis Leray for the 1875 première | |

| Librettist | |

| Language | French |

| Based on | Carmen by Prosper Mérimée |

| Premiere | |

Bizet died suddenly after the 33rd performance, unaware that the work would achieve international acclaim within the following ten years. Carmen has since become one of the most popular and frequently performed operas in the classical canon; the "Habanera" from act 1 and the "Toreador Song" from act 2 are among the best known of all operatic arias.

The opera is written in the genre of opéra comique with musical numbers separated by dialogue. It is set in southern Spain and tells the story of the downfall of Don José, a naïve soldier who is seduced by the wiles of the fiery gypsy Carmen. José abandons his childhood sweetheart and deserts from his military duties, yet loses Carmen's love to the glamorous torero Escamillo, after which José kills her in a jealous rage. The depictions of proletarian life, immorality, and lawlessness, and the tragic death of the main character on stage, broke new ground in French opera and were highly controversial.

After the premiere, most reviews were critical, and the French public was generally indifferent. Carmen initially gained its reputation through a series of productions outside France, and was not revived in Paris until 1883. Thereafter, it rapidly acquired popularity at home and abroad. Later commentators have asserted that Carmen forms the bridge between the tradition of opéra comique and the realism or verismo that characterised late 19th-century Italian opera.

The music of Carmen has since been widely acclaimed for brilliance of melody, harmony, atmosphere, and orchestration, and for the skill with which Bizet musically represented the emotions and suffering of his characters. After the composer's death, the score was subject to significant amendment, including the introduction of recitative in place of the original dialogue; there is no standard edition of the opera, and different views exist as to what versions best express Bizet's intentions. The opera has been recorded many times since the first acoustical recording in 1908, and the story has been the subject of many screen and stage adaptations.

Background

In the Paris of the 1860s, despite being a Prix de Rome laureate, Bizet struggled to get his stage works performed. The capital's two main state-funded opera houses—the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique—followed conservative repertoires that restricted opportunities for young native talent.[1] Bizet's professional relationship with Léon Carvalho, manager of the independent Théâtre Lyrique company, enabled him to bring to the stage two full-scale operas, Les pêcheurs de perles (1863) and La jolie fille de Perth (1867), but neither enjoyed much public success.[2][3]

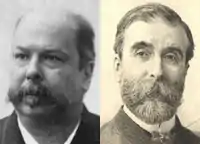

When artistic life in Paris resumed after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, Bizet found wider opportunities for the performance of his works; his one-act opera Djamileh opened at the Opéra-Comique in May 1872. Although this failed and was withdrawn after 11 performances,[4] it led to a further commission from the theatre, this time for a full-length opera for which Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy would provide the libretto.[5] Halévy, who had written the text for Bizet's student opera Le docteur Miracle (1856), was a cousin of Bizet's wife, Geneviève;[6] he and Meilhac had a solid reputation as the librettists of many of Jacques Offenbach's operettas.[7]

Bizet was delighted with the Opéra-Comique commission, and expressed to his friend Edmund Galabert his satisfaction in "the absolute certainty of having found my path".[5] The subject of the projected work was a matter of discussion between composer, librettists and the Opéra-Comique management; Adolphe de Leuven, on behalf of the theatre, made several suggestions that were politely rejected. It was Bizet who first proposed an adaptation of Prosper Mérimée's novella Carmen.[8] Mérimée's story is a blend of travelogue and adventure yarn, possibly inspired by the writer's lengthy travels in Spain in 1830, and had originally been published in 1845 in the journal Revue des deux Mondes.[9] It may have been influenced in part by Alexander Pushkin's 1824 poem "The Gypsies",[10] a work Mérimée had translated into French;[n 1] it has also been suggested that the story was developed from an incident told to Mérimée by his friend the Countess Montijo.[9] Bizet may first have encountered the story during his Rome sojourn of 1858–60, since his journals record Mérimée as one of the writers whose works he absorbed in those years.[12]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 3 March 1875 Conductor: Adolphe Deloffre[13] |

|---|---|---|

| Carmen, A Gypsy Girl | mezzo-soprano | Célestine Galli-Marié |

| Don José, Corporal of Dragoons | tenor | Paul Lhérie |

| Escamillo, Toreador | bass-baritone | Jacques Bouhy |

| Micaëla, A Village Maiden | soprano | Marguerite Chapuy |

| Zuniga, Lieutenant of Dragoons | bass | Eugène Dufriche |

| Moralès, Corporal of Dragoons | baritone | Edmond Duvernoy |

| Frasquita, Companion of Carmen | soprano | Alice Ducasse |

| Mercédès, Companion of Carmen | mezzo-soprano | Esther Chevalier |

| Lillas Pastia, an innkeeper | spoken | M. Nathan |

| Le Dancaïre, smuggler | baritone | Pierre-Armand Potel |

| Le Remendado, smuggler | tenor | Barnolt |

| A guide | spoken | M. Teste |

| Chorus: Soldiers, young men, cigarette factory girls, Escamillo's supporters, Gypsies, merchants and orange sellers, police, bullfighters, people, urchins. | ||

- Cast details are as provided by Mina Curtiss (Bizet and His World, 1959) from the original piano and vocal score. The stage designs are credited to Charles Ponchard.[14]

Synopsis

- Place: Seville, Spain, and surrounding hills

- Time: Around 1820

Act 1

A square, in Seville. On the right, a door to the tobacco factory. At the back, a bridge. On the left, a guardhouse.

A group of soldiers relax in the square, waiting for the changing of the guard and commenting on the passers-by ("Sur la place, chacun passe"). Micaëla appears, seeking José. Moralès tells her that "José is not yet on duty" and invites her to wait with them. She declines, saying she will return later. José arrives with the new guard, who is greeted and imitated by a crowd of urchins ("Avec la garde montante").

As the factory bell rings, the cigarette girls emerge and exchange banter with young men in the crowd ("La cloche a sonné"). Carmen enters and sings her provocative habanera on the untameable nature of love ("L'amour est un oiseau rebelle"). The men plead with her to choose a lover, and after some teasing she throws a flower to Don José, who thus far has been ignoring her but is now annoyed by her insolence.

As the women go back to the factory, Micaëla returns and gives José a letter and a kiss from his mother ("Parle-moi de ma mère!"). He reads that his mother wants him to return home and marry Micaëla, who retreats in shy embarrassment on learning this. Just as José declares that he is ready to heed his mother's wishes, the women stream from the factory in great agitation. Zuniga, the officer of the guard, learns that Carmen has attacked a woman with a knife. When challenged, Carmen answers with mocking defiance ("Tra la la... Coupe-moi, brûle-moi"); Zuniga orders José to tie her hands while he prepares the prison warrant. Left alone with José, Carmen beguiles him with a seguidilla, in which she sings of a night of dancing and passion with her lover—whoever that may be—in Lillas Pastia's tavern. Confused yet mesmerised, José agrees to free her hands; as she is led away she pushes her escort to the ground and runs off laughing. José is arrested for dereliction of duty.

Act 2

Lillas Pastia's Inn

Two months have passed. Carmen and her friends Frasquita and Mercédès are entertaining Zuniga and other officers ("Les tringles des sistres tintaient") in Pastia's inn. Carmen is delighted to learn of José's release from two months' detention. Outside, a chorus and procession announces the arrival of the toreador Escamillo ("Vivat, vivat le Toréro"). Invited inside, he introduces himself with the "Toreador Song" ("Votre toast, je peux vous le rendre") and sets his sights on Carmen, who brushes him aside. Lillas Pastia hustles the crowds and the soldiers away.

When only Carmen, Frasquita and Mercédès remain, smugglers Dancaïre and Remendado arrive and reveal their plans to dispose of some recently acquired contraband ("Nous avons en tête une affaire"). Frasquita and Mercédès are keen to help them, but Carmen refuses, since she wishes to wait for José. After the smugglers leave, José arrives. Carmen treats him to a private exotic dance ("Je vais danser en votre honneur ... La la la"), but her song is joined by a distant bugle call from the barracks. When José says he must return to duty, she mocks him, and he answers by showing her the flower that she threw to him in the square ("La fleur que tu m'avais jetée"). Unconvinced, Carmen demands he show his love by leaving with her. José refuses to desert, but as he prepares to depart, Zuniga enters looking for Carmen. He and José fight. Carmen summons her gypsy comrades, who restrain Zuniga. Having attacked a superior officer, José now has no choice but to join Carmen and the smugglers ("Suis-nous à travers la campagne").

Act 3

A wild spot in the mountains

Carmen and José enter with the smugglers and their booty ("Écoute, écoute, compagnons"); Carmen has now become bored with José and tells him scornfully that he should go back to his mother. Frasquita and Mercédès amuse themselves by reading their fortunes from the cards; Carmen joins them and finds that the cards are foretelling her death, and José's. The smugglers depart to transport their goods while the women distract the local customs officers. José is left behind on guard duty.

Micaëla enters with a guide, seeking José and determined to rescue him from Carmen ("Je dis que rien ne m'épouvante"). On hearing a gunshot she hides in fear; it is José, who has fired at an intruder who proves to be Escamillo. José's pleasure at meeting the bullfighter turns to anger when Escamillo declares his infatuation with Carmen. The pair fight ("Je suis Escamillo, toréro de Grenade"), but are interrupted by the returning smugglers and girls ("Holà, holà José"). As Escamillo leaves he invites everyone to his next bullfight in Seville. Micaëla is discovered; at first, José will not leave with her despite Carmen's mockery, but he agrees to go when told that his mother is dying. He departs, vowing he will return. Escamillo is heard in the distance, singing the toreador's song.

Act 4

.jpg.webp)

A square in Seville. At the back, the walls of an ancient amphitheatre

Zuniga, Frasquita and Mercédès are among the crowd awaiting the arrival of the bullfighters ("Les voici ! Voici la quadrille!"). Escamillo enters with Carmen, and they express their mutual love ("Si tu m'aimes, Carmen"). As Escamillo goes into the arena, Frasquita and Mercédès warn Carmen that José is nearby, but Carmen is unafraid and willing to speak to him. Alone, she is confronted by the desperate José ("C'est toi !", "C'est moi !"). While he pleads vainly for her to return to him, cheers are heard from the arena. As José makes his last entreaty, Carmen contemptuously throws down the ring he gave her and attempts to enter the arena. He then stabs her, and as Escamillo is acclaimed by the crowds, Carmen dies. José kneels and sings "Ah! Carmen! ma Carmen adorée!"; as the crowd exits the arena, José confesses to killing Carmen.

Creation

Writing history

Meilhac and Halévy were a long-standing duo with an established division of labour: Meilhac, who was completely unmusical, wrote the dialogue and Halévy the verses.[13] There is no clear indication of when work began on Carmen.[15] Bizet and the two librettists were all in Paris during 1873 and easily able to meet; thus there is little written record or correspondence relating to the beginning of the collaboration.[16] The libretto was prepared in accordance with the conventions of opéra comique, with dialogue separating musical numbers.[n 2] It deviates from Mérimée's novella in a number of significant respects. In the original, events are spread over a much longer period of time, and much of the main story is narrated by José from his prison cell, as he awaits execution for Carmen's murder. Micaëla does not feature in Mérimée's version, and the Escamillo character is peripheral—a picador named Lucas who is only briefly Carmen's grand passion. Carmen has a husband called Garcia, whom José kills during a quarrel.[18] In the novella, Carmen and José are presented much less sympathetically than they are in the opera; Bizet's biographer Mina Curtiss comments that Mérimée's Carmen, on stage, would have seemed "an unmitigated and unconvincing monster, had her character not been simplified and deepened".[19]

With rehearsals due to begin in October 1873, Bizet began composing in or around January of that year, and by the summer had completed the music for the first act and perhaps sketched more. At that point, according to Bizet's biographer Winton Dean, "some hitch at the Opéra-Comique intervened", and the project was suspended for a while.[20] One reason for the delay may have been the difficulties in finding a singer for the title role.[21] Another was a split that developed between the joint directors of the theatre, Camille du Locle and Adolphe de Leuven, over the advisability of staging the work. De Leuven had vociferously opposed the entire notion of presenting so risqué a story in what he considered a family theatre and was sure that audiences would be frightened away. He was assured by Halévy that the story would be toned down, that Carmen's character would be softened, and offset by Micaëla, described by Halévy as "a very innocent, very chaste young girl". Furthermore, the gypsies would be presented as comic characters, and Carmen's death would be overshadowed at the end by "triumphal processions, ballets and joyous fanfares". De Leuven reluctantly agreed, but his continuing hostility towards the project led to his resignation from the theatre early in 1874.[22]

After the various delays, Bizet appears to have resumed work on Carmen early in 1874. He completed the draft of the composition—1,200 pages of music—in the summer, which he spent at the artists' colony at Bougival, just outside Paris. He was pleased with the result, informing a friend: "I have written a work that is all clarity and vivacity, full of colour and melody".[23] During the period of rehearsals, which began in October, Bizet repeatedly altered the music—sometimes at the request of the orchestra who found some of it impossible to perform,[21] sometimes to meet the demands of individual singers, and otherwise in response to the demands of the theatre's management.[24] The vocal score that Bizet published in March 1875 shows significant changes from the version of the score that he sold to the publishers, Choudens, in January 1875; the conducting score used at the premiere differs from each of these documents. There is no definitive edition, and there are differences among musicologists about which version represents the composer's true intentions.[21][25] Bizet also changed the libretto, reordering sequences and imposing his own verses where he felt that the librettists had strayed too far from the character of Mérimée's original.[26] Among other changes, he provided new words for Carmen's "Habanera",[25] and rewrote the text of Carmen's solo in the act 3 card scene. He also provided a new opening line for the "Seguidilla" in act 1.[27]

Characterisation

Most of the characters in Carmen—the soldiers, the smugglers, the Gypsy women and the secondary leads Micaëla and Escamillo—are reasonably familiar types within the opéra comique tradition, although drawing them from proletarian life was unusual.[15] The two principals, José and Carmen, lie outside the genre. While each is presented quite differently from Mérimée's portrayals of a murderous brigand and a treacherous, amoral schemer,[19] even in their relatively sanitised forms neither corresponds to the norms of opéra comique. They are more akin to the verismo style that would find fuller expression in the works of Puccini.[28]

Dean considers that José is the central figure of the opera: "It is his fate rather than Carmen's that interests us".[29] The music characterizes his gradual decline, act by act, from honest soldier to deserter, vagabond and finally murderer.[21] In act 1 he is a simple countryman aligned musically with Micaëla; in act 2 he evinces a greater toughness, the result of his experiences as a prisoner, but it is clear that by the end of the act his infatuation with Carmen has driven his emotions beyond control. Dean describes him in act 3 as a trapped animal who refuses to leave his cage even when the door is opened for him, ravaged by a mix of conscience, jealousy and despair. In the final act his music assumes a grimness and purposefulness that reflects his new fatalism: "He will make one more appeal; if Carmen refuses, he knows what to do".[29]

Carmen herself, says Dean, is a new type of operatic heroine representing a new kind of love, not the innocent kind associated with the "spotless soprano" school, but something altogether more vital and dangerous. Her capriciousness, fearlessness and love of freedom are all musically represented: "She is redeemed from any suspicion of vulgarity by her qualities of courage and fatalism so vividly realised in the music".[21][30] Curtiss suggests that Carmen's character, spiritually and musically, may be a realisation of the composer's own unconscious longing for a freedom denied to him by his stifling marriage.[31] Harold C. Schonberg likens Carmen to "a female Don Giovanni. She would rather die than be false to herself".[32] The dramatic personality of the character, and the range of moods she is required to express, call for exceptional acting and singing talents. This has deterred some of opera's most distinguished exponents; Maria Callas, though she recorded the part, never performed it on stage.[33] The musicologist Hugh Macdonald observes that "French opera never produced another femme as fatale as Carmen", though she may have influenced some of Massenet's heroines. Macdonald suggests that outside the French repertoire, Richard Strauss's Salome and Alban Berg's Lulu "may be seen as distant degenerate descendants of Bizet's temptress".[34]

Bizet was reportedly contemptuous of the music that he wrote for Escamillo: "Well, they asked for ordure, and they've got it", he is said to have remarked about the toreador's song—but, as Dean comments, "the triteness lies in the character, not in the music".[29] Micaëla's music has been criticised for its "Gounodesque" elements, although Dean maintains that her music has greater vitality than that of any of Gounod's own heroines.[35]

Performance history

Assembling the cast

The search for a singer-actress to play Carmen began in the summer of 1873. Press speculation favoured Zulma Bouffar, who was perhaps the librettists' preferred choice. She had sung leading roles in many of Offenbach's operas, but she was unacceptable to Bizet and was turned down by du Locle as unsuitable.[36] In September an approach was made to Marie Roze, well known for previous triumphs at the Opéra-Comique, the Opéra and in London. She refused the part when she learned that she would be required to die on stage.[37] The role was then offered to Célestine Galli-Marié, who agreed to terms with du Locle after several months' negotiation.[38] Galli-Marié, a demanding and at times tempestuous performer, would prove a staunch ally of Bizet, often supporting his resistance to demands from the management that the work should be toned down.[39] At the time it was generally believed that she and the composer were conducting a love affair during the months of rehearsal.[15]

The leading tenor part of Don José was given to Paul Lhérie, a rising star of the Opéra-Comique who had recently appeared in works by Massenet and Delibes. He would later become a baritone, and in 1887 sang the role of Zurga in the Covent Garden premiere of Les pêcheurs de perles.[40] Jacques Bouhy, engaged to sing Escamillo, was a young Belgian-born baritone who had already appeared in demanding roles such as Méphistophélès in Gounod's Faust and as Mozart's Figaro.[41] Marguerite Chapuy, who sang Micaëla, was at the beginning of a short career in which she was briefly a star at London's Theatre Royal, Drury Lane; the impresario James H. Mapleson thought her "one of the most charming vocalists it has been my pleasure to know". However, she married and left the stage altogether in 1876, refusing Mapleson's considerable cash inducements to return.[42]

Premiere and initial run

Because rehearsals did not start until October 1874 and lasted longer than anticipated, the premiere was delayed.[43] The final rehearsals went well, and in a generally optimistic mood the first night was fixed for 3 March 1875, the day on which, coincidentally, Bizet's appointment as a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour was formally announced.[n 3] The premiere, which was conducted by Adolphe Deloffre, was attended by many of Paris's leading musical figures, including Massenet, Offenbach, Delibes and Gounod;[45] during the performance the last-named was overheard complaining bitterly that Bizet had stolen the music of Micaëla's act 3 aria from him: "That melody is mine!"[46] Halévy recorded his impressions of the premiere in a letter to a friend; the first act was evidently well received, with applause for the main numbers and numerous curtain calls. The first part of act 2 also went well, but after the toreador's song there was, Halévy noted, "coldness". In act 3 only Micaëla's aria earned applause as the audience became increasingly disconcerted. The final act was "glacial from first to last", and Bizet was left "only with the consolations of a few friends".[45] The critic Ernest Newman wrote later that the sentimentalist Opéra-Comique audience was "shocked by the drastic realism of the action" and by the low standing and defective morality of most of the characters.[47] According to the composer Benjamin Godard, Bizet retorted, in response to a compliment, "Don't you see that all these bourgeois have not understood a wretched word of the work I have written for them?"[48] In a different vein, shortly after the work had concluded, Massenet sent Bizet a congratulatory note: "How happy you must be at this time—it's a great success!".[49]

The general tone of the next day's press reviews ranged from disappointment to outrage. The more conservative critics complained about "Wagnerism" and the subordination of the voice to the noise of the orchestra.[50] There was consternation that the heroine was an amoral seductress rather than a woman of virtue;[51] Galli-Marié's interpretation of the role was described by one critic as "the very incarnation of vice".[50] Others compared the work unfavourably with the traditional Opéra-Comique repertoire of Auber and Boieldieu. Léon Escudier in L'Art Musical called Carmen's music "dull and obscure ... the ear grows weary of waiting for the cadence that never comes".[52] It seemed that Bizet had generally failed to fulfill expectations, both of those who (given Halévy's and Meilhac's past associations) had expected something in the Offenbach mould, and of critics such as Adolphe Jullien who had anticipated a Wagnerian music drama. Among the few supportive critics was the poet Théodore de Banville; writing in Le National, he applauded Bizet for presenting a drama with real men and women instead of the usual Opéra-Comique "puppets".[53]

In its initial run at the Opéra-Comique, Carmen provoked little public enthusiasm; it shared the theatre for a while with Verdi's much more popular Requiem.[54] Carmen was often performed to half-empty houses, even when the management gave away large numbers of tickets.[21] Early on 3 June, the day after the opera's 33rd performance, Bizet died suddenly of heart disease, at the age of 36. It was his wedding anniversary. That night's performance was cancelled; the tragic circumstances brought a temporary increase in public interest during the brief period before the season ended.[15] Du Locle brought Carmen back in November 1875, with the original cast, and it ran for a further 12 performances until 15 February 1876 to give a year's total for the original production of 48.[55] Among those who attended one of these later performances was Tchaikovsky, who wrote to his benefactor, Nadezhda von Meck: "Carmen is a masterpiece in every sense of the word ... one of those rare creations which expresses the efforts of a whole musical epoch".[56] After the final performance, Carmen was not seen in Paris again until 1883.[21]

Early revivals

Shortly before his death Bizet signed a contract for a production of Carmen by the Vienna Court Opera. For this version, first staged on 23 October 1875, Bizet's friend Ernest Guiraud replaced the original dialogue with recitatives, to create a "grand opera" format. Guiraud also reorchestrated music from Bizet's L'Arlésienne suite to provide a spectacular ballet for Carmen's second act.[57] Shortly before the initial Vienna performance, the Court Opera's director Franz von Jauner decided to use parts of the original dialogue along with some of Guiraud's recitatives; this hybrid and the full recitative version became the norms for productions of the opera outside France for most of the next century.[58]

Despite its deviations from Bizet's original format, and some critical reservations, the 1875 Vienna production was a great success with the city's public. It also won praise from both Wagner and Brahms. The latter reportedly saw the opera 20 times, and said that he would have "gone to the ends of the earth to embrace Bizet".[57] The Viennese triumph began the opera's rapid ascent towards worldwide fame. In February 1876 it began a run in Brussels at La Monnaie; it returned there the following year, with Galli-Marié in the title role, and thereafter became a permanent fixture in the Brussels repertory. On 17 June 1878 Carmen was produced in London, at Her Majesty's Theatre, where Minnie Hauk began her long association with the part of Carmen. A parallel London production at Covent Garden, with Adelina Patti, was cancelled when Patti withdrew. The successful Her Majesty's production, sung in Italian, had an equally enthusiastic reception in Dublin. On 23 October 1878 the opera received its American premiere, at the New York Academy of Music, and in the same year was introduced to Saint Petersburg.[55]

In the following five years performances were given in numerous American and European cities. The opera found particular favour in Germany, where the Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, apparently saw it on 27 different occasions and where Friedrich Nietzsche opined that he "became a better man when Bizet speaks to me".[59][60] Carmen was also acclaimed in numerous French provincial cities including Marseille, Lyon and, in 1881, Dieppe, where Galli-Marié returned to the role. In August 1881 the singer wrote to Bizet's widow to report that Carmen's Spanish premiere, in Barcelona, had been "another great success".[61] But Carvalho, who had assumed the management of the Opéra-Comique, thought the work immoral and refused to reinstate it. Meilhac and Hálevy were more prepared to countenance a revival, provided that Galli-Marié had no part in it; they blamed her interpretation for the relative failure of the opening run.[60]

In April 1883 Carvalho finally revived Carmen at the Opéra-Comique, with Adèle Isaac featuring in an under-rehearsed production that removed some of the controversial aspects of the original. Carvalho was roundly condemned by the critics for offering a travesty of what had come to be regarded as a masterpiece of French opera; nevertheless, this version was acclaimed by the public and played to full houses. In October Carvalho yielded to pressure and revised the production; he brought back Galli-Marié, and restored the score and libretto to their 1875 forms.[62]

Worldwide success

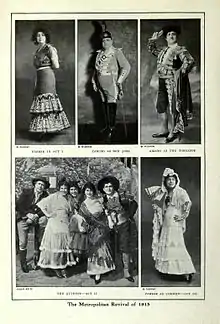

On 9 January 1884, Carmen was given its first New York Metropolitan Opera performance, to a mixed critical reception. The New York Times welcomed Bizet's "pretty and effective work", but compared Zelia Trebelli's interpretation of the title role unfavourably with that of Minnie Hauk.[63] Thereafter Carmen was quickly incorporated into the Met's regular repertory. In February 1906 Enrico Caruso sang José at the Met for the first time; he continued to perform in this role until 1919, two years before his death.[63] On 17 April 1906, on tour with the Met, he sang the role at the Grand Opera House in San Francisco. Afterwards he sat up until 3 am reading the reviews in the early editions of the following day's papers.[64] Two hours later he was awakened by the first violent shocks of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, after which he and his fellow performers made a hurried escape from the Palace Hotel.[65]

The popularity of Carmen continued through succeeding generations of American opera-goers; by the beginning of 2011 the Met alone had performed it almost a thousand times.[63] It enjoyed similar success in other American cities and in all parts of the world, in many different languages.[66] Carmen's habanera from act 1, and the toreador's song "Votre toast" from act 2, are among the most popular and best-known of all operatic arias,[67] the latter "a splendid piece of swagger" according to Newman, "against which the voices and the eyebrows of purists have long been raised in vain".[68] Most of the productions outside France followed the example created in Vienna and incorporated lavish ballet interludes and other spectacles, a practice which Mahler abandoned in Vienna when he revived the work there in 1900.[47] In 1919, Bizet's aged contemporary Camille Saint-Saëns was still complaining about the "strange idea" of adding a ballet, which he considered "a hideous blemish in that masterpiece", and he wondered why Bizet's widow, at that time still living, permitted it.[69]

At the Opéra-Comique, after its 1883 revival, Carmen was always presented in the dialogue version with minimal musical embellishments.[70] By 1888, the year of the 50th anniversary of Bizet's birth, the opera had been performed there 330 times;[66] by 1938, his centenary year, the total of performances at the theatre had reached 2,271.[71] However, outside France the practice of using recitatives remained the norm for many years; the Carl Rosa Opera Company's 1947 London production, and Walter Felsenstein's 1949 staging at the Berlin Komische Oper, are among the first known instances in which the dialogue version was used other than in France.[70][72] Neither of these innovations led to much change in practice; a similar experiment was tried at Covent Garden in 1953 but hurriedly withdrawn, and the first American production with spoken dialogue, in Colorado in 1953, met with a similar fate.[70]

Dean has commented on the dramatic distortions that arise from the suppression of the dialogue; the effect, he says, is that the action moves forward "in a series of jerks, rather instead of by smooth transition", and that most of the minor characters are substantially diminished.[70][73] Only late in the 20th century did dialogue versions become common in opera houses outside France, but there is still no universally recognised full score. Fritz Oeser's 1964 edition is an attempt to fill this gap, but in Dean's view is unsatisfactory. Oeser reintroduces material removed by Bizet during the first rehearsals, and ignores many of the late changes and improvements that the composer made immediately before the first performance;[21] he thus, according to Susan McClary, "inadvertently preserves as definitive an early draft of the opera".[25] In the early 21st century new editions were prepared by Robert Didion and Richard Langham-Smith, published by Schott and Peters respectively.[74] Each departs significantly from Bizet's vocal score of March 1875, published during his lifetime after he had personally corrected the proofs; Dean believes that this vocal score should be the basis of any standard edition.[21] Lesley Wright, a contemporary Bizet scholar, remarks that, unlike his compatriots Rameau and Debussy, Bizet has not been accorded a critical edition of his principal works;[75] should this transpire, she says, "we might expect yet another scholar to attempt to refine the details of this vibrant score which has so fascinated the public and performers for more than a century".[74] Meanwhile, Carmen's popularity endures; according to Macdonald: "The memorability of Bizet's tunes will keep the music of Carmen alive in perpetuity", and its status as a popular classic is unchallenged by any other French opera.[34]

Music

Hervé Lacombe, in his survey of 19th-century French opera, contends that Carmen is one of the few works from that large repertory to have stood the test of time.[76] While he places the opera firmly within the long opéra comique tradition,[77] Macdonald considers that it transcends the genre and that its immortality is assured by "the combination in abundance of striking melody, deft harmony and perfectly judged orchestration".[15] Dean sees Bizet's principal achievement in the demonstration of the main actions of the opera in the music, rather than in the dialogue, writing that "Few artists have expressed so vividly the torments inflicted by sexual passions and jealousy". Dean places Bizet's realism in a different category from the verismo of Puccini and others; he likens the composer to Mozart and Verdi in his ability to engage his audiences with the emotions and sufferings of his characters.[21]

Bizet, who had never visited Spain, sought out appropriate ethnic material to provide an authentic Spanish flavour to his music.[21] Carmen's habanera is based on an idiomatic song, "El Arreglito", by the Spanish composer Sebastián Yradier (1809–65).[n 4] Bizet had taken this to be a genuine folk melody; when he learned its recent origin he added a note to the vocal score, crediting Yradier.[79] He used a genuine folksong as the source of Carmen's defiant "Coupe-moi, brûle-moi" while other parts of the score, notably the "Seguidilla", utilise the rhythms and instrumentation associated with flamenco music. However, Dean insists that "[t]his is a French, not a Spanish opera"; the "foreign bodies", while they undoubtedly contribute to the unique atmosphere of the opera, form only a small ingredient of the complete music.[78]

The prelude to act 1 combines three recurrent themes: the entry of the bullfighters from act 4, the refrain from the Toreador Song from act 2, and the motif that, in two slightly differing forms, represents both Carmen herself and the fate that she personifies.[n 5] This motif, played on clarinet, bassoon, cornet and cellos over tremolo strings, concludes the prelude with an abrupt crescendo.[78][80] When the curtain rises a light and sunny atmosphere is soon established, and pervades the opening scenes. The mock solemnities of the changing of the guard, and the flirtatious exchanges between the townsfolk and the factory girls, precede a mood change when a brief phrase from the fate motif announces Carmen's entrance. After her provocative habanera, with its persistent insidious rhythm and changes of key, the fate motif sounds in full when Carmen throws her flower to José before departing.[81] This action elicits from José a passionate A major solo that Dean suggests is the turning-point in his musical characterisation.[29] The softer vein returns briefly, as Micaëla reappears and joins with José in a duet to a warm clarinet and strings accompaniment. The tranquillity is shattered by the women's noisy quarrel, Carmen's dramatic re-entry and her defiant interaction with Zuniga. After her beguiling "Seguidilla" provokes José to an exasperated high A sharp shout, Carmen's escape is preceded by the brief but disconcerting reprise of a fragment from the habanera.[78][81] Bizet revised this finale several times to increase its dramatic effect.[25]

Act 2 begins with a short prelude, based on a melody that José will sing offstage before his next entry.[29] A festive scene in the inn precedes Escamillo's tumultuous entrance, in which brass and percussion provide prominent backing while the crowd sings along.[82] The quintet that follows is described by Newman as "of incomparable verve and musical wit".[83] José's appearance precipitates a long mutual wooing scene; Carmen sings, dances and plays the castanets; a distant cornet-call summoning José to duty is blended with Carmen's melody so as to be barely discernible.[84] A muted reference to the fate motif on an English horn leads to José's "Flower Song", a flowing continuous melody that ends pianissimo on a sustained high B-flat.[85] José's insistence that, despite Carmen's blandishments, he must return to duty leads to a quarrel; the arrival of Zuniga, the consequent fight and José's unavoidable ensnarement into the lawless life culminates musically in the triumphant hymn to freedom that closes the act.[82]

The prelude to act 3 was originally intended for Bizet's L'Arlésienne score. Newman describes it as "an exquisite miniature, with much dialoguing and intertwining between the woodwind instruments".[86] As the action unfolds, the tension between Carmen and José is evident in the music. In the card scene, the lively duet for Frasquita and Mercédès turns ominous when Carmen intervenes; the fate motif underlines her premonition of death. Micaëla's aria, after her entry in search of José, is a conventional piece, though of deep feeling, preceded and concluded by horn calls.[87] The middle part of the act is occupied by Escamillo and José, now acknowledged as rivals for Carmen's favour. The music reflects their contrasting attitudes: Escamillo remains, says Newman, "invincibly polite and ironic", while José is sullen and aggressive.[88] When Micaëla pleads with José to go with her to his mother, the harshness of Carmen's music reveals her most unsympathetic side. As José departs, vowing to return, the fate theme is heard briefly in the woodwind.[89] The confident, off-stage sound of the departing Escamillo singing the toreador's refrain provides a distinct contrast to José's increasing desperation.[87]

The final act is prefaced with a lively orchestral piece derived from Manuel García's short operetta El Criado Fingido.[78] After the opening crowd scene, the bullfighters' march is led by the children's chorus; the crowd hails Escamillo before his short love scene with Carmen.[90] The long finale, in which José makes his last pleas to Carmen and is decisively rejected, is punctuated at critical moments by enthusiastic off-stage shouts from the bullfighting arena. As José kills Carmen, the chorus sing the refrain of the Toreador Song off-stage; the fate motif, which has been suggestively present at various points during the act, is heard fortissimo, together with a brief reference to Carmen's card scene music.[25] Jose's last words of love and despair are followed by a final long chord, on which the curtain falls without further musical or vocal comment.[91]

Musical numbers

Numbers are from the vocal score (English version) printed by G. Schirmer Inc., New York, 1958 from Guiraud's 1875 arrangement.

|

Act 1

|

Act 2

|

Act 3

Act 4

|

Recordings

Carmen has been the subject of many recordings, beginning with early wax cylinder recordings of excerpts in the 1890s, a nearly complete performance in German from 1908 with Emmy Destinn in the title role,[92][93] and a complete 1911 Opéra-Comique recording in French. Since then, many of the leading opera houses and artistes have recorded the work, in both studio and live performances.[94] Over the years many versions have been commended and reissued.[95][96] From the mid-1990s numerous video recordings have become available. These include David McVicar's Glyndebourne production of 2002, and the Royal Opera productions of 2007 and 2010, each designed by Francesca Zambello.[94]

Adaptations

In 1883, the Spanish violinist and composer Pablo de Sarasate (1844–1908) wrote a Carmen Fantasy for violin, described as "ingenious and technically difficult".[97] Ferruccio Busoni's 1920 piece, Piano Sonatina No. 6 (Fantasia da camera super Carmen), is based on themes from Carmen.[98] In 1967, the Russian composer Rodion Shchedrin adapted parts of the Carmen music into a ballet, the Carmen Suite, written for his wife Maya Plisetskaya, then the Bolshoi Ballet's principal ballerina.[99][100]

In 1983 the stage director Peter Brook produced an adaptation of Bizet's opera known as La Tragedie de Carmen in collaboration with the writer Jean-Claude Carrière and the composer Marius Constant. This 90-minute version focused on four main characters, eliminating choruses and the major arias were reworked for chamber orchestra. Brook first produced it in Paris, and it has since been performed in many cities.[101]

.jpg.webp)

The character "Carmen" has been a regular subject of film treatment since the earliest days of cinema. The films were made in various languages and interpreted by several cultures, and have been created by prominent directors including Gerolamo Lo Savio (1909), Raoul Walsh (1915) with Theda Bara,[102] Cecil B. DeMille (1915),[103] and The Loves of Carmen (1948) with Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford, directed by Charles Vidor. Otto Preminger's 1954 Carmen Jones, with an all-black cast, is based on the 1943 Oscar Hammerstein Broadway musical of the same name, an adaptation of the opera transposed to 1940s' North Carolina extending to Chicago.[104] Carlos Saura (1983) (who made a flamenco-based dance film with two levels of story telling), Peter Brook (1983) (filming his compressed La Tragédie de Carmen), and Jean-Luc Godard (1984).[105] Francesco Rosi's film of 1984, with Julia Migenes and Plácido Domingo, is generally faithful to the original story and to Bizet's music.[106] Carmen on Ice (1990), starring Katarina Witt, Brian Boitano and Brian Orser, was inspired by Witt's gold medal-winning performance during the 1988 Winter Olympics.[107] Robert Townsend's 2001 film, Carmen: A Hip Hopera, starring Beyoncé Knowles, is a more recent attempt to create an African-American version.[108] Carmen was interpreted in modern ballet by the South African dancer and choreographer Dada Masilo in 2010.[109]

References

Notes

- In her act 1 defiance of Zuniga, Carmen sings the words "Coupe-moi, brûle-moi", which are taken from Mérimée's translation from Pushkin.[11]

- The term opéra comique, as applied to 19th-century French opera, did not imply "comic opera" but rather the use of spoken dialogue in place of recitative, as a distinction from grand opera.[17]

- Bizet had been informed of the impending award early in February, and had told Carvalho's wife that he owed the honour to her husband's promotion of his work.[44]

- Dean writes that Bizet improved considerably on the original melody; he "transformed it from a drawing-room piece into a potent instrument of characterisation". Likewise, the melody from Manuel García used in the act 4 prelude has been developed from "a rambling recitation to a taut masterpiece".[78]

- The form in which the motif appears in the prelude prefigures the dramatic act 4 climax to the opera. When the theme is used to represent Carmen, the orchestration is lighter, reflecting her "fickle, laughing, elusive character".[78]

Footnotes

- Steen, p. 586

- Curtiss, pp. 131–42

- Dean 1965, pp. 69–73

- Dean 1965, pp. 97–98

- Dean 1965, p. 100

- Curtiss, p. 41

- Dean 1965, p. 84

- McClary, p. 15

- "Prosper Mérimée's Novella, Carmen". Columbia University. 2003. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- Dean 1965, p. 230

- Newman, pp. 267–68

- Dean 1965, p. 34

- Dean 1965, pp. 112–13

- Curtiss, p. 390

- Macdonald, Hugh. "Bizet, Georges (Alexandre-César-Léopold)". Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 18 February 2012. (subscription required)

- Curtiss, p. 352

- Bartlet, Elizabeth C. "Opéra comique". Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 29 March 2012. (subscription required)

- Newman, pp. 249–52

- Curtiss, pp. 397–98

- Dean 1965, p. 105

- Dean 1980, pp. 759–61

- Curtiss, p. 351

- Dean 1965, pp. 108–09

- Dean 1965, p. 215(n)

- McClary, pp. 25–26

- Nowinski, Judith (May 1970). "Sense and Sound in Georges Bizet's Carmen". The French Review. 43 (6): 891–900. JSTOR 386524. (subscription required)

- Dean 1965, pp. 214–17

- Dean 1965, p. 244

- Dean 1965, pp. 221–24

- Dean 1965, pp. 224–25

- Curtiss, pp. 405–06

- Schonberg, p. 35

- Azaola 2003, pp. 9–10.

- Macdonald, Hugh. "Carmen". Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 29 March 2012. (subscription required)

- Dean 1965, p. 226

- Curtiss, p. 355

- Dean 1965, p. 110

- Curtiss, p. 364

- Curtiss, p. 383

- Forbes, Elizabeth. "Lhérie [Lévy], Paul". Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 1 March 2012. (subscription required)

- Forbes, Elizabeth. "Bouhy, Jacques(-Joseph-André)". Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 1 March 2012. (subscription required)

- Mapleson, James H. (1888). "Marguerite Chapuy". The Mapleson Memoirs, Volume I, Chapter XI. Chicago, New York and San Francisco: Belford, Clarke & Co. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014.

- Dean 1965, pp. 111–12

- Curtiss, pp. 386–87

- Dean 1965, pp. 114–15

- Curtiss, p. 391

- Newman, p. 248

- Dean 1965, p. 116

- Curtiss, pp. 395–96

- Dean 1965, p. 117

- Steen, pp. 604–05

- Dean 1965, p. 118

- Curtiss, pp. 408–09

- Curtiss, p. 379

- Curtiss, pp. 427–28

- Weinstock 1946, p. 115.

- Curtiss, p. 426

- Dean 1965, p. 129(n)

- Nietzsche 1911, p. 3.

- Curtiss, pp. 429–31

- Curtiss, p. 430

- Dean 1965, pp. 130–31

- "Carmen, 9 January 1884, Met Performance CID: 1590, performance details and reviews". Metropolitan Opera. Retrieved 28 July 2018.)

- Winchester, pp. 206–09

- Winchester, pp. 221–23

- Curtiss, pp. 435–36

- "Ten Pieces". BBC. 2016. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Newman, p. 274

- Curtiss, p. 462

- Dean 1965, pp. 218–21

- Steen, p. 606

- Neef, p. 62

- McClary, p. 18

- Wright, pp. xviii–xxi

- Wright, pp. ix–x

- Lacombe 2001, p. 1.

- Lacombe 2001, p. 233.

- Dean 1965, pp. 228–32

- Carr, Bruce; et al. "Iradier (Yradier) (y Salaverri), Sebastián de". Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 18 February 2012. (subscription required)

- Newman, p. 255

- Azaola 2003, pp. 11–14.

- Azaola 2003, pp. 16–18.

- Newman, p. 276

- Newman, p. 280

- Newman, p. 281

- Newman, p. 284

- Azaola 2003, pp. 19–20.

- Newman, p. 289

- Newman, p. 291

- Azaola 2003, p. 21.

- Newman, p. 296

- "Carmen: The First Complete Recording". Marston Records. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- "Recordings of Carmen by Georges Bizet on file". Operadis. Archived from the original on 8 April 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- "Bizet: Carmen – All recordings". Presto Classical. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- March, Ivan (ed.); Greenfield, Edward; Layton, Robert (1993). The Penguin Guide to Opera on Compact Discs. London: Penguin Books. pp. 25–28. ISBN 0-14-046957-5.

- Roberts, David, ed. (2005). The Classical Good CD & DVD Guide. Teddington: Haymarket Consumer. pp. 172–174. ISBN 0-86024-972-7.

- "Sarasate, Pablo de". Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 5 June 2012. (subscription required)

- "Busoni: Sonatina No. 6 (Chamber Fantasy on Themes from Bizet's Carmen)". Presto Classical. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Walket, Jonathan, and Latham, Alison. "Shchedrin, Rodion Konstantinovich". Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 14 March 2012. (subscription required)

- Greenfield, Edward (April 1969). "Bizet (arr. Shchedrin). Carmen – Ballet". Gramophone: 48.

- "La Tragédie de Carmen, Naples, Florida; Opera Naples, Arts Naples World Festival; Opera News, 1 May 2015; accessed 13 April 2019

- Carmen (1915, Walsh) at IMDb

- Carmen (1915, DeMille) at IMDb

- Crowther, Bosley (29 October 1954). "Up-dated Translation of Bizet Work Bows". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012.

- Canby, Vincent (3 August 1984). "Screen: Godard's First Name: Carmen Opens". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Canby, Vincent (20 September 1984). "Bizet's Carmen from Francesco Rosi". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016.

- Carmen on Ice (1990) at IMDb

- Carmen: A Hip Hopera at IMDb

- Curnow, Robyn. "Dada Masilo: South African dancer who breaks the rules". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

Sources

- Azaola, Juan Ramon, ed. (2003). A Season of Opera on DVD:, Part 4: Carmen. Madrid: Del Prado. ISBN 84-9798-071-9.

- Curtiss, Mina (1959). Bizet and His World. London: Secker & Warburg. OCLC 505162968.

- Dean, Winton (1965). Georges Bizet: His Life and Work. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. OCLC 643867230.

- Dean, Winton (1980). "Bizet, Georges (Alexandre César Léopold)". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 2. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Lacombe, Hervé (2001). The Keys to French Opera in the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21719-5.

- McClary, Susan (1992). Georges Bizet: Carmen. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39897-5.

- Neef, Sigrid, ed. (2000). Opera: Composers, Works, Performers (English ed.). Cologne: Könemann. ISBN 3-8290-3571-3.

- Newman, Ernest (1958). Great Operas. 1. New York: Vintage Books. OCLC 592622247.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich (1911). The Case Of Wagner (Vol. 8 in The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche). Translated by Anthony M. Ludovici. London and Edinburgh: T. N. Foulis. OCLC 418505.

- Schonberg, Harold C. (1975). The Lives of the Great Composers: Volume 2. London: Futura Publications Ltd. ISBN 0-86007-723-3.

- Steen, Michael (2003). The Life and Times of the Great Composers. London: Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-84046-679-9.

- Weinstock, Herbert (1946). Tchaikovsky. London: Cassel. OCLC 397644.

- Winchester, Simon (2005). A Crack in the Edge of the World. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-101634-5.

- Wright, Lesley A. (2000). "Introduction: Looking at the Sources and Editions of Bizet's Carmen". In Dibbern, Mary (ed.). Carmen: A Performance Guide. New York: Pendragon Press. ISBN 1-57647-032-6.

External links

| French Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carmen. |

- Carmen: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project These include:

- Full orchestral score, Choudens 1877 (republished by Könemann, 1994)

- Full orchestral score, Peters 1920 (republished by Kalmus, 1987)

- Vocal score, Choudens 1875

- Bizet, Georges (1958). Carmen: Opera in Four Acts. New York: G. Schirmer. OCLC 475327. (Vocal score, with words provided in English and French, based on the 1875 arrangement of Ernest Guiraud)

- Carmen by Prosper Mérimée (1845), Project Gutenberg

- Libretto (in French and English)

- Carmen on IMDb