Cello

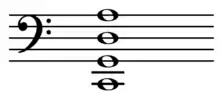

The cello (/ˈtʃɛloʊ/ CHEL-oh; plural celli or cellos) or violoncello (/ˌvaɪələnˈtʃɛloʊ/ VY-ə-lən-CHEL-oh;[1] Italian pronunciation: [vjolonˈtʃɛllo]) is a bowed (and occasionally plucked) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually tuned in perfect fifths: from low to high, C2, G2, D3 and A3. The viola's four strings are each an octave higher. Music for the cello is generally written in the bass clef, with tenor clef and treble clef used for higher-range passages.

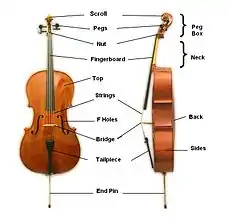

Cello, front and side view. The endpin at the bottom is retracted or removed for easier storage and transportation, and adjusted for height in accordance to the player. | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Violoncello |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.322-71 (Composite chordophone sounded by a bow) |

| Developed | c. 1660 from bass violin |

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

Played by a cellist or violoncellist, it enjoys a large solo repertoire with and without accompaniment, as well as numerous concerti. As a solo instrument, the cello uses its whole range, from bass to soprano, and in chamber music such as string quartets and the orchestra's string section, it often plays the bass part, where it may be reinforced an octave lower by the double basses. Figured bass music of the Baroque-era typically assumes a cello, viola da gamba or bassoon as part of the basso continuo group alongside chordal instruments such as organ, harpsichord, lute or theorbo. Cellos are found in many other ensembles, from modern Chinese orchestras to cello rock bands.

Etymology

The name cello is derived from the ending of the Italian violoncello,[2] which means "little violone". Violone ("big viola") was a large-sized member of viol (viola da gamba) family or the violin (viola da braccio) family. The term "violone" today usually refers to the lowest-pitched instrument of the viols, a family of stringed instruments that went out of fashion around the end of the 17th century in most countries except England and, especially, France, where they survived another half-century before the louder violin family came into greater favour in that country as well. In modern symphony orchestras, it is the second largest stringed instrument (the double bass is the largest). Thus, the name "violoncello" contained both the augmentative "-one" ("big") and the diminutive "-cello" ("little"). By the turn of the 20th century, it had become common to shorten the name to 'cello, with the apostrophe indicating the missing stem.[3] It is now customary to use "cello" without apostrophe as the full designation.[3] Viol is derived from the root viola, which was derived from Medieval Latin vitula, meaning stringed instrument.

General description

Tuning

Cellos are tuned in fifths, starting with C2 (two octaves below middle C), followed by G2, D3, and then A3. It is tuned in the exact same intervals and strings as the viola, but an octave lower. Unlike the violin or viola but similar to the double bass, the cello has an endpin that rests on the floor to support the instrument's weight. The cello is most closely associated with European classical music. The instrument is a part of the standard orchestra, as part of the string section, and is the bass voice of the string quartet (although many composers give it a melodic role as well), as well as being part of many other chamber groups.

Works

Among the most well-known Baroque works for the cello are Johann Sebastian Bach's six unaccompanied Suites. Other significant include Sonatas and Concertos by Vivaldi, and earlier works by Gabrieli, Geminiani, and Bononcini. As a basso continuo instrument basso continuo the cello may have been used in works by Francesca Caccini (1587–1641), Barbara Strozzi (1619–1677) with pieces such as Il primo libro di madrigali, per 2–5 voci e basso continuo, op. 1 and Elisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre (1665–1729) who wrote six sonatas for violin and basso continuo.

From the Classical era, the two concertos by Joseph Haydn in C major and D major stand out, as do the five sonatas for cello and pianoforte of Ludwig van Beethoven, which span the important three periods of his compositional evolution. Other outstanding examples include the three Concerti by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Capricci by dall'Abaco, and Sonatas by Flackton, Boismortier, and Luigi Boccherini. A Divertimento for Piano, Clarinet, Viola and Cello is among the surviving works by Duchess Anna Amalia of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1739–1807).

Well-known works of the Romantic era include the Robert Schumann Concerto, the Antonín Dvořák Concerto, the first Camille Saint-Saëns Concerto, as well as the two sonatas and the Double Concerto by Johannes Brahms. A review of compositions for cello in the Romantic era must include the German composer Fanny Mendelssohn (1805–1847) who wrote the Fantasy in G minor for cello and piano[4] and a Capriccio in A-flat for cello.[5]

Compositions from the late-19th and early 20th century include three cello sonatas (including the Cello Sonata in C Minor written in 1880) by Dame Ethel Smyth (1858–1944), Edward Elgar's Cello Concerto in E minor, Claude Debussy's Sonata for Cello and Piano, and unaccompanied cello sonatas by Zoltán Kodály and Paul Hindemith. Pieces including cello were written by American Music Center founder Marion Bauer (1882–1955) (two trio sonatas for flute, cello, and piano) and Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901–1953) (Diaphonic suite No. 2 for bassoon and cello).

The cello's versatility made it popular with many composers in this era, such as Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich, Benjamin Britten, György Ligeti, Witold Lutoslawski and Henri Dutilleux. Polish composer Grażyna Bacewicz (1909–1969) was writing for cello in the mid 20th century with Concerto No. 1 for Cello and Orchestra (1951), Concerto No. 2 for Cello and Orchestra (1963) and in 1964 composed her Quartet for four cellos.

Well-known cellists from the 20th century include Jacqueline du Pré, Pablo Casals, Yo-Yo Ma, Emanuel Feuermann, Guilhermina Suggia, Mstislav Rostropovich and Beatrice Harrison. Others include Raya Garbousova, Anner Bylsma, Zara Nelsova, Alfred Wallenstein, Han-Na Chang, Mischa Maisky, Hildur Gudnadottir, and Gregor Piatigorsky. See the comprehensive list of cellists here.

In the 2010s, the instrument is found in popular music, but was more commonly used in 1970s pop and disco music. Today it is sometimes featured in pop and rock recordings, examples of which are noted later in this article. The cello has also appeared in major hip-hop and R & B performances, such as singers Rihanna and Ne-Yo's 2007 performance at the American Music Awards.[6] The instrument has also been modified for Indian classical music by Nancy Lesh and Saskia Rao-de Haas.[5]

History

The violin family, including cello-sized instruments, emerged c. 1500 as a family of instruments distinct from the viola da gamba family. The earliest depictions of the violin family, from northern Italy c. 1530, show three sizes of instruments, roughly corresponding to what we now call violins, violas, and cellos. Contrary to a popular misconception, the cello did not evolve from the viola da gamba, but existed alongside it for about two and a half centuries. The violin family is also known as the viola da braccio (meaning viola of the arm) family, a reference to the primary way the members of the family are held. This is to distinguish it from the viola da gamba (meaning viola of the leg) family, in which all the members are all held with the legs. The likely predecessors of the violin family include the lira da braccio and the rebec. The earliest surviving cellos are made by Andrea Amati, the first known member of the celebrated Amati family of luthiers.[7]

The direct ancestor to the violoncello was the bass violin. Monteverdi referred to the instrument as "basso de viola da braccio" in Orfeo (1607). Although the first bass violin, possibly invented as early as 1538, was most likely inspired by the viol, it was created to be used in consort with the violin. The bass violin was actually often referred to as a "violone", or "large viola", as were the viols of the same period. Instruments that share features with both the bass violin and the viola da gamba appear in Italian art of the early 16th century.

The invention of wire-wound strings (fine wire around a thin gut core), around 1660 in Bologna, allowed for a finer bass sound than was possible with purely gut strings on such a short body. Bolognese makers exploited this new technology to create the cello, a somewhat smaller instrument suitable for solo repertoire due to both the timbre of the instrument and the fact that the smaller size made it easier to play virtuosic passages. This instrument had disadvantages as well, however. The cello's light sound was not as suitable for church and ensemble playing, so it had to be doubled by organ, theorbo, or violone.

Around 1700, Italian players popularized the cello in northern Europe, although the bass violin (basse de violon) continued to be used for another two decades in France.[8] Many existing bass violins were literally cut down in size to convert them into cellos according to the smaller pattern developed by Stradivarius, who also made a number of old pattern large cellos (the 'Servais').[9] The sizes, names, and tunings of the cello varied widely by geography and time.[9] The size was not standardized until around 1750.

Despite similarities to the viola da gamba, the cello is actually part of the viola da braccio family, meaning "viol of the arm", which includes, among others, the violin and viola. Though paintings like Bruegel's "The Rustic Wedding", and Jambe de Fer in his Epitome Musical suggest that the bass violin had alternate playing positions, these were short-lived and the more practical and ergonomic a gamba position eventually replaced them entirely.

Baroque-era cellos differed from the modern instrument in several ways. The neck has a different form and angle, which matches the baroque bass-bar and stringing.[10][11] Modern cellos have an endpin at the bottom to support the instrument (and transmit some of the sound through the floor),[12] while Baroque cellos are held only by the calves of the player. Modern bows curve in and are held at the frog; Baroque bows curve out and are held closer to the bow's point of balance. Modern strings normally have a metal core, although some use a synthetic core; Baroque strings are made of gut, with the G and C strings wire-wound. Modern cellos often have fine-tuners connecting the strings to the tailpiece, which makes it much easier to tune the instrument, but such pins are rendered ineffective by the flexibility of the gut strings used on Baroque cellos. Overall, the modern instrument has much higher string tension than the Baroque cello,[13] resulting in a louder, more projecting tone, with fewer overtones.

Few educational works specifically devoted to the cello existed before the 18th century and those that do exist contain little value to the performer beyond simple accounts of instrumental technique. One of the earliest cello manuals is Michel Corrette's Méthode, thèorique et pratique pour apprendre en peu de temps le violoncelle dans sa perfection (Paris, 1741).[14]

Modern use

Orchestral

Cellos are part of the standard symphony orchestra, which usually includes eight to twelve cellists. The cello section, in standard orchestral seating, is located on stage left (the audience's right) in the front, opposite the first violin section. However, some orchestras and conductors prefer switching the positioning of the viola and cello sections. The principal cellist is the section leader, determining bowings for the section in conjunction with other string principals, playing solos, and leading entrances (when the section begins to play its part). Principal players always sit closest to the audience.

The cellos are a critical part of orchestral music; all symphonic works involve the cello section, and many pieces require cello soli or solos. Much of the time, cellos provide part of the low-register harmony for the orchestra. Often, the cello section plays the melody for a brief period, before returning to the harmony role. There are also cello concertos, which are orchestral pieces that feature a solo cellist accompanied by an entire orchestra.

Solo

There are numerous cello concertos – where a solo cello is accompanied by an orchestra – notably 25 by Vivaldi, 12 by Boccherini, at least three by Haydn, three by C. P. E. Bach, two by Saint-Saëns, two by Dvořák, and one each by Robert Schumann, Lalo, and Elgar. There were also some composers who, while not otherwise cellists, did write cello-specific repertoire, such as Nikolaus Kraft who wrote six cello concertos. Beethoven's Triple Concerto for Cello, Violin and Piano and Brahms' Double Concerto for Cello and Violin are also part of the concertante repertoire although in both cases the cello shares solo duties with at least one other instrument. Moreover, several composers wrote large-scale pieces for cello and orchestra, which are concertos in all but name. Some familiar "concertos" are Richard Strauss' tone poem Don Quixote, Tchaikovsky's Variations on a Rococo Theme, Bloch's Schelomo and Bruch's Kol Nidrei.

In the 20th century, the cello repertoire grew immensely. This was partly due to the influence of virtuoso cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, who inspired, commissioned, and premiered dozens of new works. Among these, Prokofiev's Symphony-Concerto, Britten's Cello Symphony, the concertos of Shostakovich and Lutosławski as well as Dutilleux's Tout un monde lointain... have already become part of the standard repertoire. Other major composers who wrote concertante works for him include Messiaen, Jolivet, Berio, and Penderecki. In addition, Arnold, Barber, Glass, Hindemith, Honegger, Ligeti, Myaskovsky, Penderecki, Rodrigo, Villa-Lobos and Walton also wrote major concertos for other cellists, notably for Gaspar Cassadó, Aldo Parisot, Gregor Piatigorsky, Siegfried Palm and Julian Lloyd Webber.

There are also many sonatas for cello and piano. Those written by Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Brahms, Grieg, Rachmaninoff, Debussy, Fauré, Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Poulenc, Carter, and Britten are particularly well known.

Other important pieces for cello and piano include Schumann's five Stücke im Volkston and transcriptions like Schubert's Arpeggione Sonata (originally for arpeggione and piano), César Franck's Cello Sonata (originally a violin sonata, transcribed by Jules Delsart with the composer's approval), Stravinsky's Suite italienne (transcribed by the composer – with Gregor Piatigorsky – from his ballet Pulcinella) and Bartók's first rhapsody (also transcribed by the composer, originally for violin and piano).

There are pieces for cello solo, J. S. Bach's six Suites for Cello (which are among the best-known solo cello pieces), Kodály's Sonata for Solo Cello and Britten's three Cello Suites. Other notable examples include Hindemith's and Ysaÿe's Sonatas for Solo Cello, Dutilleux's Trois Strophes sur le Nom de Sacher, Berio's Les Mots Sont Allés, Cassadó's Suite for Solo Cello, Ligeti's Solo Sonata, Carter's two Figments and Xenakis' Nomos Alpha and Kottos.

Quartets and other ensembles

The cello is a member of the traditional string quartet as well as string quintets, sextet or trios and other mixed ensembles. There are also pieces written for two, three, four, or more cellos; this type of ensemble is also called a "cello choir" and its sound is familiar from the introduction to Rossini's William Tell Overture as well as Zaccharia's prayer scene in Verdi's Nabucco. Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture also starts with a cello ensemble, with four cellos playing the top lines and two violas playing the bass lines. As a self-sufficient ensemble, its most famous repertoire is Heitor Villa-Lobos' first of his Bachianas Brasileiras for cello ensemble (the fifth is for soprano and 8 cellos). Other examples are Offenbach's cello duets, quartet, and sextet, Pärt's Fratres for eight cellos and Boulez' Messagesquisse for seven cellos, or even Villa-Lobos' rarely played Fantasia Concertante (1958) for 32 cellos. The 12 cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (or "the Twelve" as they have since taken to being called) specialize in this repertoire and have commissioned many works, including arrangements of well-known popular songs.

Popular music, jazz, world music and neoclassical

The cello is less common in popular music than in classical music. Several bands feature a cello in their standard line-up, including Hoppy Jones of the Ink Spots and Joe Kwon of the Avett Brothers. The more common use in pop and rock is to bring the instrument in for a particular song. In the 1960s, artists such as the Beatles and Cher used the cello in popular music, in songs such as The Beatles' "Yesterday", "Eleanor Rigby" and "Strawberry Fields Forever", and Cher's "Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)". "Good Vibrations" by the Beach Boys includes the cello in its instrumental ensemble, which includes a number of instruments unusual for this sort of music. Bass guitarist Jack Bruce, who had originally studied music on a performance scholarship for cello, played a prominent cello part in "As You Said" on Cream's Wheels of Fire studio album (1968).

In the 1970s, the Electric Light Orchestra enjoyed great commercial success taking inspiration from so-called "Beatlesque" arrangements, adding the cello (and violin) to the standard rock combo line-up and in 1978 the UK based rock band, Colosseum II, collaborated with cellist Julian Lloyd Webber on the recording Variations. Most notably, Pink Floyd included a cello solo in their 1970 epic instrumental "Atom Heart Mother". Bass guitarist Mike Rutherford of Genesis was originally a cellist and included some cello parts in their Foxtrot album.

Established non-traditional cello groups include Apocalyptica, a group of Finnish cellists best known for their versions of Metallica songs, Rasputina, a group of cellists committed to an intricate cello style intermingled with Gothic music, the Massive Violins, an ensemble of seven singing cellists known for their arrangements of rock, pop and classical hits, Von Cello, a cello fronted rock power trio, Break of Reality who mix elements of classical music with the more modern rock and metal genre, Cello Fury, a cello rock band that performs original rock/classical crossover music, and Jelloslave, a Minneapolis-based Cello duo with two percussionists. These groups are examples of a style that has become known as cello rock. The crossover string quartet bond also includes a cellist. Silenzium and Cellissimo Quartet are Russian (Novosibirsk) groups playing rock and metal and having more and more popularity in Siberia. Cold Fairyland from Shanghai, China is using a cello along a Pipa as the main solo instrument to create East meets West progressive (folk) rock.

More recent bands using the cello are Clean Bandit, Aerosmith, The Auteurs, Nirvana, Oasis, Smashing Pumpkins, James, Talk Talk, Phillip Phillips, OneRepublic, Electric Light Orchestra and the baroque rock band Arcade Fire. An Atlanta-based trio, King Richard's Sunday Best, also uses a cellist in their lineup. So-called "chamber pop" artists like Kronos Quartet, The Vitamin String Quartet and Margot and the Nuclear So and So's have also recently made cello common in modern alternative rock. Heavy metal band System of a Down has also made use of the cello's rich sound. The indie rock band The Stiletto Formal are known for using a cello as a major staple of their sound, similarly, the indie rock band Canada employs two cello players in their lineup. The orch-rock group, The Polyphonic Spree, which has pioneered the use of stringed and symphonic instruments, employs the cello in very creative ways for many of their "psychedelic-esque" melodies. The first wave screamo band I Would Set Myself On Fire For You featured a cello as well as a viola to create a more folk-oriented sound. The band, Panic! at the Disco uses a cello in their song, "Build God, Then We'll Talk". The lead vocalist of the band, Brendon Urie, also did the recording of the cello solo. The Lumineers added cellist Nela Pekarek to the band in 2010. She plays cello, sings harmony, and duets.

In jazz, bassists Oscar Pettiford and Harry Babasin were among the first to use the cello as a solo instrument; both tuned their instrument in fourths, an octave above the double bass. Fred Katz (who was not a bassist) was one of the first notable jazz cellists to use the instrument's standard tuning and arco technique. Contemporary jazz cellists include Abdul Wadud, Diedre Murray, Ron Carter, Dave Holland, David Darling, Lucio Amanti, Akua Dixon, Ernst Reijseger, Fred Lonberg-Holm, Tom Cora and Erik Friedlander. Modern musical theatre pieces like Jason Robert Brown's The Last Five Years, Duncan Sheik's Spring Awakening, Adam Guettel's Floyd Collins, and Ricky Ian Gordon's My Life with Albertine use small string ensembles (including solo cellos) to a prominent extent.

In Indian Classical music Saskia Rao-de Haas is a well-established soloist as well as playing duets with her sitarist husband Pt. Shubhendra Rao. Other cellists performing Indian classical music are Nancy Lesh (Dhrupad) and Anup Biswas. Both Rao and Lesh play the cello sitting cross-legged on the floor.

The cello can also be used in bluegrass and folk music, with notable players including Ben Sollee of the Sparrow Quartet and the "Cajun cellist" Sean Grissom, as well as Vyvienne Long who, in addition to her own projects, has played for those of Damien Rice. Cellists such as Natalie Haas, Abby Newton, and Liz Davis Maxfield have contributed significantly to the use of cello playing in Celtic folk music, often with the cello featured as a primary melodic instrument and employing the skills and techniques of traditional fiddle playing. Lindsay Mac is becoming well known for playing the cello like a guitar, with her cover of The Beatles' "Blackbird".

Construction

The cello is typically made from carved wood, although other materials such as carbon fiber or aluminum may be used. A traditional cello has a spruce top, with maple for the back, sides, and neck. Other woods, such as poplar or willow, are sometimes used for the back and sides. Less expensive cellos frequently have tops and backs made of laminated wood. Laminated cellos are widely used in elementary and secondary school orchestras and youth orchestras, because they are much more durable than carved wood cellos (i.e., they are less likely to crack if bumped or dropped) and they are much less expensive.

The top and back are traditionally hand-carved, though less expensive cellos are often machine-produced. The sides, or ribs, are made by heating the wood and bending it around forms. The cello body has a wide top bout, narrow middle formed by two C-bouts, and wide bottom bout, with the bridge and F holes just below the middle. The top and back of the cello has a decorative border inlay known as purfling. While purfling is attractive, it is also functional: if the instrument is struck, the purfling can prevent cracking of the wood. A crack may form at the rim of the instrument but spreads no further. Without purfling, cracks can spread up or down the top or back. Playing, traveling and the weather all affect the cello and can increase a crack if purfling is not in place. Less expensive instruments typically have painted purfling.

Alternative materials

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) as well as German luthier G.A. Pfretzschner produced an unknown number of aluminum cellos (in addition to aluminum double basses and violins).[15] Cello manufacturer Luis & Clark constructs cellos from carbon fibre. Carbon fibre instruments are particularly suitable for outdoor playing because of the strength of the material and its resistance to humidity and temperature fluctuations. Luis & Clark has produced over 1000 cellos, some of which are owned by cellists such as Yo-Yo Ma[16] and Josephine van Lier.[17]

Neck, fingerboard, pegbox, and scroll

Above the main body is the carved neck. The neck has a curved cross-section on its underside, which is where the player's thumb runs along the neck during playing. The neck leads to a pegbox and the scroll, which are all normally carved out of a single piece of wood, usually maple. The fingerboard is glued to the neck and extends over the body of the instrument. The fingerboard is given a curved shape, matching the curve on the bridge. Both the fingerboard and bridge need to be curved so that the performer can bow individual strings. If the cello were to have a flat fingerboard and bridge, as with a typical guitar, the performer would only be able to bow the leftmost and rightmost two strings or bow all the strings. The performer would not be able to play the inner two strings alone.

The nut is a raised piece of wood, fitted where the fingerboard meets the pegbox, in which the strings rest in shallow slots or grooves to keep them the correct distance apart. The pegbox houses four tapered tuning pegs, one for each string. The pegs are used to tune the cello by either tightening or loosening the string. The pegs are called "friction pegs", because they maintain their position by friction. The scroll is a traditional ornamental part of the cello and a feature of all other members of the violin family. Ebony is usually used for the tuning pegs, fingerboard, and nut, but other hardwoods, such as boxwood or rosewood, can be used. Black fittings on low-cost instruments are often made from inexpensive wood that has been blackened or "ebonized" to look like ebony, which is much harder and more expensive. Ebonized parts such as tuning pegs may crack or split, and the black surface of the fingerboard will eventually wear down to reveal the lighter wood underneath.

Strings

Historically, cello strings had cores made out of catgut, which, despite its name is made from dried out sheep or goat intestines. Most modern strings used in the 2010s are wound with metallic materials like aluminum, titanium and chromium. Cellists may mix different types of strings on their instruments. The pitches of the open strings are C, G, D, and A (black note heads in the playing range figure above), unless alternative tuning (scordatura) is specified by the composer. Some composers (e.g. Ottorino Respighi in the final movement of ‘’The Pines of Rome’’) ask that the low C be tuned down to a B-flat so that the performer can play a different low note on the lowest open string.

Tailpiece and endpin

The tailpiece and endpin are found in the lower part of the cello. The tailpiece is the part of the cello to which the "ball ends" of the strings are attached by passing them through holes. The tailpiece is attached to the bottom of the cello. The tailpiece is traditionally made of ebony or another hardwood, but can also be made of plastic or steel on lower-cost instruments. It attaches the strings to the lower end of the cello and can have one or more fine tuners. The fine tuners are used to make smaller adjustments to the pitch of the string. The fine tuners can increase the tension of each string (raising the pitch) or decrease the tension of the string (lowering the pitch). When the performer is putting on a new string, the fine tuner for that string is normally reset to a middle position, and then the peg is turned to bring the string up to pitch. The fine turners are used for subtle, minor adjustments to pitch, such as tuning a cello to the oboe's 440 Hz A note or to tune the cello to a piano.

The endpin or spike is made of wood, metal, or rigid carbon fiber and supports the cello in playing position. The endpin can be retracted into the hollow body of the instrument when the cello is being transported in its case. This makes the cello easier to move about. When the performer wishes to play the cello, the endpin is pulled out to lengthen it. The endpin is locked into the player's preferred length with a screw mechanism. The adjustable nature of endpins enables performers of different ages and body sizes to adjust the endpin length to suit them. In the Baroque period, the cello was held between the calves, as there was no endpin at that time. The endpin was "introduced by Adrien Servais c. 1845 to give the instrument greater stability".[18] Modern endpins are retractable and adjustable; older ones were removed when not in use. (The word "endpin" sometimes also refers to the button of wood located at this place in all instruments in the violin family, but this is usually called "tailpin".[19]) The sharp tip of the cello's endpin is sometimes capped with a rubber tip that protects the tip from dulling and prevents the cello from slipping on the floor. Many cellists use a rubber pad with a metal cup to keep the tip from slipping on the floor. A number of accessories to keep the endpin from slipping; these include ropes that attach to the chair leg and other devices.

Bridge and f-holes

The bridge holds the strings above the cello and transfers their vibrations to the top of the instrument and the soundpost inside (see below). The bridge is not glued but rather held in place by the tension of the strings. The bridge is usually positioned by the cross point of the "f-hole" (i.e., where the horizontal line occurs in the "f"). The f-holes, named for their shape, are located on either side of the bridge and allow air to move in and out of the instrument as part of the sound-production process. They probably actually stand for an old-style medial S, for words related to Sound. The f-holes also act as access points to the interior of the cello for repairs or maintenance. Sometimes a small length of rubber hose containing a water-soaked sponge, called a Dampit, is inserted through the f-holes and serves as a humidifier. This keeps the wood components of the cello from drying out.

Internal features

Internally, the cello has two important features: a bass bar, which is glued to the underside of the top of the instrument, and a round wooden sound post, a solid wooden cylinder which is wedged between the top and bottom plates. The bass bar, found under the bass foot of the bridge, serves to support the cello's top and distribute the vibrations from the strings to the body of the instrument. The soundpost, found under the treble side of the bridge, connects the back and front of the cello. Like the bridge, the soundpost is not glued but is kept in place by the tensions of the bridge and strings. Together, the bass bar and sound post transfer the strings' vibrations to the top (front) of the instrument (and to a lesser extent the back), acting as a diaphragm to produce the instrument's sound.

Glue

Cellos are constructed and repaired using hide glue, which is strong but reversible, allowing for disassembly when needed. Tops may be glued on with diluted glue since some repairs call for the removal of the top. Theoretically, hide glue is weaker than the body's wood, so as the top or back shrinks side-to-side, the glue holding it lets go and the plate does not crack. Cellists repairing cracks in their cello do not use regular wood glue, because it cannot be steamed open when a repair has to be made by a luthier.

Bow

Traditionally, bows are made from pernambuco or brazilwood. Both come from the same species of tree (Caesalpinia echinata), but Pernambuco, used for higher-quality bows, is the heartwood of the tree and is darker in color than brazilwood (which is sometimes stained to compensate). Pernambuco is a heavy, resinous wood with great elasticity, which makes it an ideal wood for instrument bows. Horsehair is stretched out between the two ends of the bow. The taut horsehair is drawn over the strings, while being held roughly parallel to the bridge and perpendicular to the strings, to produce sound. A small knob is twisted to increase or decrease the tension of the horsehair. The tension on the bow is released when the instrument is not being used. The amount of tension a cellist puts on the bow hair depends on the preferences of the player, the style of music being played, and for students, the preferences of their teacher.

Bows are also made from other materials, such as carbon fibre—stronger than wood—and fiberglass (often used to make inexpensive, lower-quality student bows). An average cello bow is 73 cm (29 in) long (shorter than a violin or viola bow) 3 cm (1.2 in) high (from the frog to the stick) and 1.5 cm (0.59 in) wide. The frog of a cello bow typically has a rounded corner like that of a viola bow, but is wider. A cello bow is roughly 10 g (0.35 oz) heavier than a viola bow, which in turn is roughly 10 g (0.35 oz) heavier than a violin bow.

Bow hair is traditionally horsehair, though synthetic hair, in varying colors, is also used. Prior to playing, the musician tightens the bow by turning a screw to pull the frog (the part of the bow under the hand) back and increase the tension of the hair. Rosin is applied by the player to make the hair sticky. Bows need to be re-haired periodically. Baroque style (1600–1750) cello bows were much thicker and were formed with a larger outward arch when compared to modern cello bows. The inward arch of a modern cello bow produces greater tension, which in turn gives off a louder sound.

The cello bow has also been used to play electric guitars. Jimmy Page pioneered its application on tracks such as "Dazed and Confused". The post-rock Icelandic band Sigur Rós's lead singer often plays guitar using a cello bow.

In 1989, the German cellist Michael Bach began developing a curved bow, encouraged by John Cage, Dieter Schnebel, Mstislav Rostropovich and Luigi Colani: and since then many pieces have been composed especially for it. This curved bow (BACH.Bow) is a convex curved bow which, unlike the ordinary bow, renders possible polyphonic playing on the various strings of the instrument. The solo repertoire for violin and cello by J. S. Bach the BACH.Bow is particularly suited to it: and it was developed with this in mind, polyphonic playing being required, as well as monophonic.

Physics

Physical aspects

When a string is bowed or plucked, it vibrates and moves the air around it, producing sound waves. Because the string is quite thin, not much air is moved by the string itself, and consequently, if the string was not mounted on a hollow body, the sound would be weak. In acoustic stringed instruments such as the cello, this lack of volume is solved by mounting the vibrating string on a larger hollow wooden body. The vibrations are transmitted to the larger body, which can move more air and produce a louder sound. Different designs of the instrument produce variations in the instrument's vibrational patterns and thus changes the character of the sound produced.[21] A string's fundamental pitch can be adjusted by changing its stiffness, which depends on tension and length. Tightening a string stiffens it by increasing both the outward forces along its length and the net forces it experiences during a distortion.[22] A cello can be tuned by adjusting the tension of its strings, by turning the tuning pegs mounted on its pegbox, and tension adjusters (fine tuners) on the tailpiece.

A string's length also affects its fundamental pitch. Shortening a string stiffens it by increasing its curvature during a distortion and subjecting it to larger net forces. Shortening the string also reduces its mass, but does not alter the mass per unit length, and it is the latter ratio rather than the total mass which governs the frequency. The string vibrates in a standing wave whose speed of propagation is given by √T/m, where T is the tension and m is the mass per unit length; there is a node at either end of the vibrating length, and thus the vibrating length l is half a wavelength. Since the frequency of any wave is equal to the speed divided by the wavelength, we have frequency = 1/2l × √T/m. (Note that some writers, including Muncaster (cited below) use the Greek letter μ in place of m.) Thus shortening a string increases the frequency, and thus the pitch. Because of this effect, you can raise and change the pitch of a string by pressing it against the fingerboard in the cello's neck and effectively shortening it.[23] Likewise strings with less mass per unit length, if under the same tension, will have a higher frequency and thus higher pitch than more massive strings. This is a prime reason why the different strings on all string instruments have different fundamental pitches, with the lightest strings having the highest pitches.

A played note of E or F-sharp has a frequency which is often very close to the natural resonating frequency of the body of the instrument, and if the problem is not addressed this can set the body into near resonance. This may cause an unpleasant sudden amplification of this pitch, and additionally a loud beating sound results from the interference produced between these nearby frequencies; this is known as the “wolf tone” because it is an unpleasant growling sound. The wood resonance appears to be split into two frequencies by the driving force of the sounding string. These two periodic resonances beat with each other. This wolf tone must be eliminated or significantly reduced for the cello to play the nearby notes with a pleasant tone. This can be accomplished by modifying the cello front plate, attaching a wolf eliminator (a metal cylinder or a rubber cylinder encased in metal), or moving the soundpost.[24]

When a string is bowed or plucked to produce a note, the fundamental note is accompanied by higher frequency overtones. Each sound has a particular recipe of frequencies that combine to make the total sound.[25]

Playing technique

Playing the cello is done while seated with the instrument supported on the floor by the endpin. The left-hand fingertips stop the strings on the fingerboard, determining the pitch of the fingered note. The right hand bows (or sometimes, plucks) the strings to sound the notes. The left-hand fingertips stop the strings along their length, determining the pitch of each fingered note. Stopping the string closer to the bridge results in a higher-pitched sound, because the vibrating string length has been shortened. On the contrary, a string stopped closer to the tuning pegs produces a lower sound. In the neck positions (which use just less than half of the fingerboard, nearest the top of the instrument), the thumb rests on the back of the neck; in thumb position (a general name for notes on the remainder of the fingerboard) the thumb usually rests alongside the fingers on the string and the side of the thumb is used to play notes. The fingers are normally held curved with each knuckle bent, with the fingertips in contact with the string. If a finger is required on two (or more) strings at once to play perfect fifths (in double stops or chords) it is used flat. In slower, or more expressive playing, the contact point can move slightly away from the nail to the pad of the finger, allowing a fuller vibrato.

Vibrato is a small oscillation in the pitch of a note, usually considered an expressive technique. Harmonics played on the cello fall into two classes; natural and artificial. Natural harmonics are produced by lightly touching (but not depressing) the string with the finger at certain places, and then bowing (or, rarely, plucking) the string. For example, the halfway point of the string will produce a harmonic that is one octave above the unfingered (open) string. Natural harmonics only produce notes that are part of the harmonic series on a particular string. Artificial harmonics (also called false harmonics or stopped harmonics), in which the player depresses the string fully with one finger while touching the same string lightly with another finger, can produce any note above middle C. Glissando (Italian for "sliding") is an effect played by sliding the finger up or down the fingerboard without releasing the string. This causes the pitch to rise and fall smoothly, without separate, discernible steps.

In cello playing, the bow is much like the breath of a wind instrument player. Arguably, it is a major factor in the expressiveness of the playing. The right-hand holds the bow and controls the duration and character of the notes. In general, the bow is drawn across the strings roughly halfway between the end of the fingerboard and the bridge, in a direction perpendicular to the strings; however, the player may wish to move the bow's point of contact higher or lower depending on the desired sound. The bow is held and manipulated with all five fingers of the right hand, the thumb opposite the fingers and closer to the cellist's body. Tone production and volume of sound depend on a combination of several factors. The four most important ones are weight applied to the string, the angle of the bow in relation to the string, bow speed, and the point of contact of the bow hair with the string (sometimes abbreviated WASP).

Double stops involve the playing of two notes at the same time. Two strings are fingered simultaneously, and the bow is drawn so as to sound them both at once. Typically, in pizzicato playing, the string is plucked directly with the fingers or thumb of the right hand. However, the strings may be plucked with a finger of the left hand in certain advanced pieces, either so that bowed notes can be played on another string along with pizzicato notes, or because the speed of the piece would not allow the player sufficient time to pluck with the right hand. In musical notation, pizzicato is often abbreviated as "pizz." The position of the hand in pizzicato is commonly slightly over the fingerboard and away from the bridge.

A player using the col legno technique strikes or rubs the strings with the wood of the bow rather than the hair. In spiccato playing, the bow still moves in a horizontal motion on the string, but is allowed to bounce, generating a lighter, somewhat more percussive sound. In staccato, the player moves the bow a small distance and stops it on the string, making a short sound, the rest of the written duration being taken up by silence. Legato is a technique in which notes are smoothly connected without breaks. It is indicated by a slur (curved line) above or below – depending on their position on the staff – the notes of the passage that is to be played legato.

Sul ponticello ("on the bridge") refers to bowing closer to (or nearly on) the bridge, while Sul tasto ("on the fingerboard") calls for bowing nearer to (or over) the end of the fingerboard. At its extreme, sul ponticello produces a harsh, shrill sound with emphasis on overtones and high harmonics, while sul tasto produces a more flute-like sound, with more emphasis on the fundamental frequency of the note, and softened overtones. Both techniques have been used by composers, particularly in an orchestral setting, for special sounds and effects.

Sizes

Standard-sized cellos are referred to as "full-size" or "4⁄4" but are also made in smaller (fractional) sizes, including 7⁄8, 3⁄4, 1⁄2, 1⁄4, 1⁄8, 1⁄10, and 1⁄16. The fractions refer to volume rather than length, so a 1/2 size cello is much longer than half the length of a full size. The smaller cellos are identical to standard cellos in construction, range, and usage, but are simply scaled-down for the benefit of children and shorter adults.

Cellos in sizes larger than 4⁄4 do exist, and cellists with unusually large hands may require such a non-standard instrument. Cellos made before approximately 1700 tended to be considerably larger than those made and commonly played today. Around 1680, changes in string-making technology made it possible to play lower-pitched notes on shorter strings. The cellos of Stradivari, for example, can be clearly divided into two models: the style made before 1702, characterized by larger instruments (of which only three exist in their original size and configuration), and the style made during and after 1707, when Stradivari began making smaller cellos. This later model is the design most commonly used by modern luthiers. The scale length of a 4⁄4 cello is about 70 cm (27 1⁄2 in). The new size offered fuller tonal projection and a greater range of expression. The instrument in this form was able to contribute to more pieces musically and offered the possibility of greater physical dexterity for the player to develop technique.[26]

| Approximate dimensions for 4⁄4 size cello[27] | Average size |

|---|---|

| Approximate width horizontally from A peg to C peg ends | 16.0 cm (6.3 in) |

| Back length excluding half-round where neck joins | 75.4 cm (29.7 in) |

| Upper bouts (shoulders) | 34.0 cm (13.4 in) |

| Lower bouts (hips) | 43.9 cm (17.3 in) |

| Bridge height | 8.9 cm (3.5 in) |

| Rib depth at shoulders including edges of front and back | 12.4 cm (4.9 in) |

| Rib depth at hips including edges | 12.7 cm (5.0 in) |

| Distance beneath fingerboard to surface of belly at neck join | 2.3 cm (0.9 in) |

| Bridge to back total depth | 26.7 cm (10.5 in) |

| Overall height excluding end pin | 120.9 cm (47.6 in) |

| End pin unit and spike | 5.6 cm (2.2 in) |

Accessories

There are many accessories for the cello.

- Cases are used to protect the cello and bow (or multiple bows).

- Rosin, made from resins tapped from conifers, is applied to the bow hair to increase the effectiveness of the friction, grip or bite, and allow proper sound production. Rosin may have additives to modify the friction such as beeswax, gold, silver or tin. Commonly, rosins are classified as either dark or light, referring to color.

- Endpin stops or straps (tradenames include Rock stop and Black Hole) keep the cello from sliding if the endpin does not have a rubber piece on the end, or if a floor is particularly slippery.

- Wolf tone eliminators are placed on cello strings between the tailpiece and the bridge to eliminate acoustic anomalies known as wolf tones or "wolfs".

- Mutes are used to change the sound of the cello by adding mass and stiffness to the bridge. They alter the overtone structure, modifying the timbre and reducing the overall volume of sound produced by the instrument.

- Metronomes provide a steady tempo by sounding out a certain number of beats per minute.

Instrument makers

Cellos are made by luthiers, specialists in building and repairing stringed instruments, ranging from guitars to violins. The following luthiers are notable for the cellos they have produced:

- Nicolò Amati and others in the Amati family

- Nicolò Gagliano

- Matteo Goffriller

- Giovanni Battista Guadagnini

- Giuseppe Guarneri

- Charles Mennégand

- Domenico Montagnana

- Giovanni Battista Rogeri

- Francesco Ruggieri

- Stefano Scarampella

- Antonio Stradivari

- David Tecchler

- Carlo Giuseppe Testore

- Jean Baptiste Vuillaume

Cellists

A person who plays the cello is called a cellist. For a list of notable cellists, see the list of cellists and Category:Cellists.

Famous instruments

Specific instruments are famous (or become famous) for a variety of reasons. An instrument's notability may arise from its age, the fame of its maker, its physical appearance, its acoustic properties, and its use by notable performers. The most famous instruments are generally known for all of these things. The most highly prized instruments are now collector's items and are priced beyond the reach of most musicians. These instruments are typically owned by some kind of organization or investment group, which may loan the instrument to a notable performer. (For example, the Davidov Stradivarius, which is currently in the possession of one of the most widely known living cellists, Yo-Yo Ma, is actually owned by the Vuitton Foundation.[28])

Some notable cellos:

- the "King", by Andrea Amati, is one of the oldest known cellos, built between 1538 and 1560—it is in the collection of the National Music Museum in South Dakota.[29]

- Servais Stradivarius is in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC.

- Batta-Piatigorsky Stradivarius, played by Gregor Piatigorsky.

- Davidov Stradivarius, played by Jacqueline du Pré, currently played by Yo-Yo Ma.

- Barjansky Stradivarius, played by Julian Lloyd Webber.

- Bonjour Stradivarius, played by Soo Bae.

- Paganini-Ladenburg Stradivarius, played by Clive Greensmith of the Tokyo String Quartet.

- Duport Stradivarius, formerly played by Mstislav Rostropovich.

- Piatti Stradivarius, 1720, played by Carlos Prieto

See also

- Category:Composers for cello

- Brahms guitar

- Cello Rock

- Double Concerto for Violin and Cello

- Electric cello

- List of compositions for cello and orchestra

- List of compositions for cello and organ

- List of compositions for cello and piano

- List of solo cello pieces

- Queen Elisabeth Competition § Cello

- String instrument repertoire

- Triple concerto for violin, cello, and piano

- Ütőgardon, a percussive Hungarian folk instrument similar in construction to the Cello

References

- "violoncello noun – Pronunciation". Oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- "Violoncello". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- Delbanco, Nicholas (January 1, 2001). "The Countess of Stanlein Restored". Harper's Magazine. Archived from the original on January 8, 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- Congress, The Library of. "Hensel, Fanny Mendelssohn, 1805-1847. Fantasia, cello, piano, G minor". id.loc.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- Jeal, Erica (2019-08-22). "Felix & Fanny Mendelssohn: Works for Cello and Piano review | Erica Jeal's classical album of the week". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- "Rihanna feat. Ne Yo - Umbrella & hate that i love you live american music awards 2007". YouTube. December 25, 2015.

- "Violoncello by Andrea Amati, Cremona, Mid-16th Century". collections.nmmusd.org. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- "Cello Playing in 18th Century Italy". www.cello.org. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- Cyr, Mary (1982). "Basses and basse continue in the Orchestra of the Paris Opéra 1700–1764". Early Music. X (Apr., 1982): 155–170. doi:10.1093/earlyj/10.2.155.

- "Violin (Baroque) – Early Music Instrument Database". Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- "Baroque Instruments". History Of Music. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- Marsh, Gregory and Elizabeth (March 7, 2016). "The Endpin – The Classy Musician". Theclassymusician.com. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- "Cello (Baroque) – Early Music Instrument Database". Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- "Cello Playing in 18th Century Italy". Cello.org. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- R. Skrabec, Quentin (2017). Aluminum in America: A History. McFarland. p. 88. ISBN 9781476625645.

- Chris Museler (January 18, 2009). "Cold Case: Luis and Clark Carbon Expedition for Yo-Yo Ma?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- van Lier, Josephine (2006). "Luis and Clark Carbon Fibre Cells" (PDF). Alberta String Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- Stowell, Robin (June 28, 1999). The Cambridge Companion to the Cello. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62101-4.

- Eric Halfpenny; Theodore C Grame. "Stringed instrument". britannica.com. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- As opposed to the German bow popular in baroque era, held underhand.

- Cowling, Elizabeth (1983). The cello. C. Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-684-17870-7.

- Bloomfield, Louis (2001). How things work: the physics of everyday life. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-38151-8.

- Muncaster, Roger (1993). A-level Physics. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 978-0-7487-1584-8.

- Berg, Richard E.; Stork, David G. (2005). The Physics of Sound. Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-145789-8.

- Chattopadhyay, D. (January 1, 2004). Elements Of Physics. New Age International. ISBN 978-81-224-1538-4.

- Stowell, Robin (November 13, 2003). The Cambridge Companion to the String Quartet. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00042-0.

- Alan Stevenson. "Table of 'cello measurements". Archived from the original on 2008-01-04. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- Beare, Charles; Carlson, Bruce (1993). "Foreword by Yo-Yo Ma". Antonio Stradivari: The Cremona Exhibition of 1987. London: J. & A. Beare. ISBN 0-9519397-0-X. Archived from the original on 2006-01-01. Retrieved 2008-09-26.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Collections". Nmmusd.org. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

Sources

- Stephen Bonta. "Violoncello", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (accessed January 28, 2006), grovemusic.com (subscription access).

- Cyr, Mary (April 1982). "Basses and basse continue in the Orchestra of the Paris Opéra 1700–1764". Early Music. X (2): 155–170. doi:10.1093/earlyj/10.2.155.

- Grassineau, James (1740). A Musical Dictionary. London: J. Wilcox.

VIOLONCELLO of the Italians, is properly what we call the Bass Violin with four strings, sometimes even five or six; but those are not common, the first being most used among us.

- Holman, Peter (1982). "The English Royal Violin Consort in the Sixteenth Century". Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association. 109: 39–59. doi:10.1093/jrma/109.1.39.

- Jesselson, Robert. "The Etymology of Violoncello: Implications on Literature in the Early History of the Cello". Strings Magazine. No. 22 (JAN/FEB 1991).

- "The King Violoncello by Andrea Amati, Cremona, after 1538". National Music Museum. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- Woodfield, Ian (1984) [1984]. Howard Mayer Brown; Peter le Huray; John Stevens (eds.). The Early History of the Viol. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24292-4.

- Ghigi, Marcella (1999). Il violoncello. Conoscere la tecnica per esprimere la musica. Milano: Casa Musicale Sonzogno. ISBN 88-87318-08-5. With a preface by Mario Brunello.

- Pleeth, William (1982). Cello. Kahn & Averill. ISBN 978-1-871082-38-8.

Further reading

- Machover, Tod (2007). "My Cello". In Evocative Objects: Things We Think With, Turkle, Sherry (editor), Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-20168-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cello. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Violoncello. |