Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst (born Gustavus Theodore von Holst; 21 September 1874 – 25 May 1934) was an English composer, arranger and teacher. Best known for his orchestral suite The Planets, he composed many other works across a range of genres, although none achieved comparable success. His distinctive compositional style was the product of many influences, Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss being most crucial early in his development. The subsequent inspiration of the English folksong revival of the early 20th century, and the example of such rising modern composers as Maurice Ravel, led Holst to develop and refine an individual style.

There were professional musicians in the previous three generations of Holst's family and it was clear from his early years that he would follow the same calling. He hoped to become a pianist but was prevented by neuritis in his right arm. Despite his father's reservations, he pursued a career as a composer, studying at the Royal College of Music under Charles Villiers Stanford. Unable to support himself by his compositions, he played the trombone professionally and later became a teacher—a great one, according to his colleague Ralph Vaughan Williams. Among other teaching activities, he built up a strong tradition of performance at Morley College, where he served as musical director from 1907 until 1924 and pioneered music education for women at St Paul's Girls' School, where he taught from 1905 until his death in 1934. He was the founder of a series of Whitsun music festivals, which ran from 1916 for the remainder of his life.

Holst's works were played frequently in the early years of the 20th century, but it was not until the international success of The Planets in the years immediately after the First World War that he became a well-known figure. A shy man, he did not welcome this fame and preferred to be left in peace to compose and teach. In his later years, his uncompromising, personal style of composition struck many music lovers as too austere, and his brief popularity declined. Nevertheless, he was a considerable influence on a number of younger English composers, including Edmund Rubbra, Michael Tippett and Benjamin Britten. Apart from The Planets and a handful of other works, his music was generally neglected until the 1980s, when recordings of much of his output became available.

Life and career

Family background

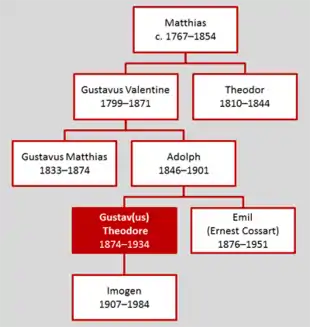

Holst was born in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, the elder of the two children of Adolph von Holst, a professional musician, and his wife, Clara Cox, née Lediard. She was of mostly British descent,[n 1] daughter of a respected Cirencester solicitor;[2] the Holst side of the family was of mixed Swedish, Latvian and German ancestry, with at least one professional musician in each of the previous three generations.[3]

One of Holst's great-grandfathers, Matthias Holst, born in Riga, Latvia, was a Baltic German; he served as composer and harp teacher to the Imperial Russian Court in St Petersburg.[4] Matthias's son Gustavus, who moved to England with his parents as a child in 1802,[5] was a composer of salon-style music and a well-known harp teacher. He appropriated the aristocratic prefix "von" and added it to the family name in the hope of gaining enhanced prestige and attracting pupils.[n 2]

Holst's father, Adolph von Holst, became organist and choirmaster at All Saints' Church, Cheltenham;[7] he also taught, and gave piano recitals.[7] His wife, Clara, a former pupil, was a talented singer and pianist. They had two sons; Gustav's younger brother, Emil Gottfried, became known as Ernest Cossart, a successful actor in the West End, New York and Hollywood.[8] Clara died in February 1882, and the family moved to another house in Cheltenham,[n 3] where Adolph recruited his sister Nina to help raise the boys. Gustav recognised her devotion to the family and dedicated several of his early compositions to her.[2] In 1885 Adolph married Mary Thorley Stone, another of his pupils. They had two sons, Matthias (known as "Max") and Evelyn ("Thorley").[11] Mary von Holst was absorbed in theosophy and not greatly interested in domestic matters. All four of Adolph's sons were subject to what one biographer calls "benign neglect",[11] and Gustav in particular was "not overburdened with attention or understanding, with a weak sight and a weak chest, both neglected—he was 'miserable and scared'."[12]

Childhood and youth

Holst was taught to play the piano and the violin; he enjoyed the former but hated the latter.[13] At the age of twelve he took up the trombone at Adolph's suggestion, thinking that playing a brass instrument might improve his asthma.[14] Holst was educated at Cheltenham Grammar School between 1886 and 1891.[15] He started composing in or about 1886; inspired by Macaulay's poem Horatius he began, but soon abandoned, an ambitious setting of the work for chorus and orchestra.[13] His early compositions included piano pieces, organ voluntaries, songs, anthems and a symphony (from 1892). His main influences at this stage were Mendelssohn, Chopin, Grieg and above all Sullivan.[16][n 4]

Adolph tried to steer his son away from composition, hoping that he would have a career as a pianist. Holst was oversensitive and miserable. His eyes were weak, but no one realised that he needed to wear spectacles. Holst's health played a decisive part in his musical future; he had never been strong, and in addition to his asthma and poor eyesight he suffered from neuritis, which made playing the piano difficult.[18] He said that the affected arm was "like a jelly overcharged with electricity".[19]

After Holst left school in 1891, Adolph paid for him to spend four months in Oxford studying counterpoint with George Frederick Sims, organist of Merton College.[20] On his return, Holst obtained his first professional appointment, aged seventeen, as organist and choirmaster at Wyck Rissington, Gloucestershire. The post brought with it the conductorship of the Bourton-on-the-Water Choral Society, which offered no extra remuneration but provided valuable experience that enabled him to hone his conducting skills.[13] In November 1891 Holst gave what was perhaps his first public performance as a pianist; he and his father played the Brahms Hungarian Dances at a concert in Cheltenham.[21] The programme for the event gives his name as "Gustav" rather than "Gustavus"; he was called by the shorter version from his early years.[21]

Royal College of Music

In 1892 Holst wrote the music for an operetta in the style of Gilbert and Sullivan, Lansdown Castle, or The Sorcerer of Tewkesbury.[22] The piece was performed at Cheltenham Corn Exchange in February 1893; it was well received and its success encouraged him to persevere with composing.[23] He applied for a scholarship at the Royal College of Music (RCM) in London, but the composition scholarship for that year was won by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.[24] Holst was accepted as a non-scholarship student, and Adolph borrowed £100 to cover the first year's expenses.[n 5] Holst left Cheltenham for London in May 1893. Money was tight, and partly from frugality and partly from his own inclination he became a vegetarian and a teetotaller.[24] Two years later he was finally granted a scholarship, which slightly eased his financial difficulties, but he retained his austere personal regime.[25]

Holst's professors at the RCM were Frederick Sharpe (piano), William Stephenson Hoyte (organ), George Case (trombone),[n 6] Georges Jacobi (instrumentation) and the director of the college, Hubert Parry (history). After preliminary lessons with W. S. Rockstro and Frederick Bridge, Holst was granted his wish to study composition with Charles Villiers Stanford.[27]

To support himself during his studies Holst played the trombone professionally, at seaside resorts in the summer and in London theatres in the winter.[28] His daughter and biographer, Imogen Holst, records that from his fees as a player "he was able to afford the necessities of life: board and lodging, manuscript paper, and tickets for standing room in the gallery at Covent Garden Opera House on Wagner evenings".[28] He secured an occasional engagement in symphony concerts, playing in 1897 under the baton of Richard Strauss at the Queen's Hall.[4]

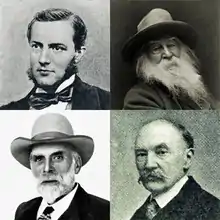

Like many musicians of his generation, Holst came under Wagner's spell. He had recoiled from the music of Götterdämmerung when he heard it at Covent Garden in 1892, but encouraged by his friend and fellow-student Fritz Hart he persevered and quickly became an ardent Wagnerite.[29] Wagner supplanted Sullivan as the main influence on his music,[30] and for some time, as Imogen put it, "ill-assimilated wisps of Tristan inserted themselves on nearly every page of his own songs and overtures."[28] Stanford admired some of Wagner's works, and had in his earlier years been influenced by him,[31] but Holst's sub-Wagnerian compositions met with his disapprobation: "It won't do, me boy; it won't do".[28] Holst respected Stanford, describing him to a fellow-pupil, Herbert Howells, as "the one man who could get any one of us out of a technical mess",[32] but he found that his fellow students, rather than the faculty members, had the greater influence on his development.[28]

In 1895, shortly after celebrating his twenty-first birthday, Holst met Ralph Vaughan Williams, who became a lifelong friend and had more influence on Holst's music than anybody else.[33] Stanford emphasised the need for his students to be self-critical, but Holst and Vaughan Williams became one another's chief critics; each would play his latest composition to the other while still working on it. Vaughan Williams later observed, "What one really learns from an Academy or College is not so much from one's official teachers as from one's fellow-students ... [we discussed] every subject under the sun from the lowest note of the double bassoon to the philosophy of Jude the Obscure.[34] In 1949 he wrote of their relationship, "Holst declared that his music was influenced by that of his friend: the converse is certainly true."[35]

The year 1895 was also the bicentenary of Henry Purcell, which was marked by various performances including Stanford conducting Dido and Aeneas at the Lyceum Theatre;[36] the work profoundly impressed Holst,[4] who over twenty years later confessed to a friend that his search for "the (or a) musical idiom of the English language" had been inspired "unconsciously" by "hearing the recits in Purcell's Dido".[37]

Another early influence was William Morris.[38] In Vaughan Williams's words, "It was now that Holst discovered the feeling of unity with his fellow men which made him afterwards a great teacher. A sense of comradeship rather than political conviction led him, while still a student, to join the Kelmscott House Socialist Club in Hammersmith."[35] At Kelmscott House, Morris's home, Holst attended lectures by his host and Bernard Shaw. His own socialism was moderate in character, but he enjoyed the club for its good company and his admiration of Morris as a man.[39] His ideals were influenced by Morris's but had a different emphasis. Morris had written, "I do not want art for a few any more than education for a few, or freedom for a few. I want all persons to be educated according to their capacity, not according to the amount of money which their parents happen to have".[40] Holst said, "'Aristocracy in art'—art is not for all but only for the chosen few—but the only way to find those few is to bring art to everyone—then the artists have a sort of masonic signal by which they recognise each other in the crowd."[n 7] He was invited to conduct the Hammersmith Socialist Choir, teaching them madrigals by Thomas Morley, choruses by Purcell, and works by Mozart, Wagner and himself.[42] One of his choristers was (Emily) Isobel Harrison (1876–1969), a beautiful soprano two years his junior. He fell in love with her; she was at first unimpressed by him, but she came round and they were engaged, though with no immediate prospect of marriage given Holst's tiny income.[42]

Professional musician

In 1898 the RCM offered Holst a further year's scholarship, but he felt that he had learned as much as he could there and that it was time, as he put it, to "learn by doing".[42] Some of his compositions were published and performed; the previous year The Times had praised his song "Light Leaves Whisper", "a moderately elaborate composition in six parts, treated with a good deal of expression and poetic feeling".[44]

Occasional successes notwithstanding, Holst found that "man cannot live by composition alone";[35] he took posts as organist at various London churches, and continued playing the trombone in theatre orchestras. In 1898 he was appointed first trombonist and répétiteur with the Carl Rosa Opera Company and toured with the Scottish Orchestra. Though a capable rather than a virtuoso player he won the praise of the leading conductor Hans Richter, for whom he played at Covent Garden.;[45] and Holst (1969), p. 20</ref> His salary was only just enough to live on,[46] and he supplemented it by playing in a popular orchestra called the "White Viennese Band", conducted by Stanislas Wurm.[47]

Holst enjoyed playing for Wurm, and learned much from him about drawing rubato from players.[48][n 8] Nevertheless, longing to devote his time to composing, Holst found the necessity of playing for "the Worm" or any other light orchestra "a wicked and loathsome waste of time".[49] Vaughan Williams did not altogether agree with his friend about this; he admitted that some of the music was "trashy" but thought it had been useful to Holst nonetheless: "To start with, the very worst a trombonist has to put up with is as nothing compared to what a church organist has to endure; and secondly, Holst is above all an orchestral composer, and that sure touch which distinguishes his orchestral writing is due largely to the fact that he has been an orchestral player; he has learnt his art, both technically and in substance, not at second hand from text books and models, but from actual live experience."[17]

With a modest income secured, Holst was able to marry Isobel; the ceremony was at Fulham Register Office on 22 June 1901. Their marriage lasted until his death; there was one child, Imogen, born in 1907.[50] In 1902 Dan Godfrey and the Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra premiered Holst's symphony The Cotswolds (Op. 8), the slow movement of which is a lament for William Morris who had died in October 1896, three years before Holst began work on the piece.[51] In 1903 Adolph von Holst died, leaving a small legacy. Holst and his wife decided, as Imogen later put it, that "as they were always hard up the only thing to do was to spend it all at once on a holiday in Germany".[52]

Composer and teacher

While in Germany, Holst reappraised his professional life, and in 1903 he decided to abandon orchestral playing to concentrate on composition.[9] His earnings as a composer were too little to live on, and two years later he accepted the offer of a teaching post at James Allen's Girls' School, Dulwich, which he held until 1921. He also taught at the Passmore Edwards Settlement, where among other innovations he gave the British premieres of two Bach cantatas.[53] The two teaching posts for which he is probably best known were director of music at St Paul's Girls' School, Hammersmith, from 1905 until his death, and director of music at Morley College from 1907 to 1924.[9]

Vaughan Williams wrote of the former establishment: "Here he did away with the childish sentimentality which schoolgirls were supposed to appreciate and substituted Bach and da Vittoria; a splendid background for immature minds."[35] Several of Holst's pupils at St Paul's went on to distinguished careers, including the soprano Joan Cross,[54] and the oboist and cor anglais player Helen Gaskell.[55]

Of Holst's impact on Morley College, Vaughan Williams wrote: "[A] bad tradition had to be broken down. The results were at first discouraging, but soon a new spirit appeared and the music of Morley College, together with its offshoot the 'Whitsuntide festival' ... became a force to be reckoned with".[35] Before Holst's appointment, Morley College had not treated music very seriously (Vaughan Williams's "bad tradition"), and at first Holst's exacting demands drove many students away. He persevered, and gradually built up a class of dedicated music-lovers.[56]

According to the composer Edmund Rubbra, who studied under him in the early 1920s, Holst was "a teacher who often came to lessons weighted, not with the learning of Prout and Stainer, but with a miniature score of Petrushka or the then recently published Mass in G minor of Vaughan Williams".[57] He never sought to impose his own ideas on his composition pupils. Rubbra recalled that he would divine a student's difficulties and gently guide him to finding the solution for himself. "I do not recall that Holst added one single note of his own to anything I wrote, but he would suggest—if I agreed!—that, given such and such a phrase, the following one would be better if it took such and such a course; if I did not see this, the point would not be insisted upon ... He frequently took away [because of] his abhorrence of unessentials."[58]

As a composer Holst was frequently inspired by literature. He set poetry by Thomas Hardy and Robert Bridges and, a particular influence, Walt Whitman, whose words he set in "Dirge for Two Veterans" and The Mystic Trumpeter (1904). He wrote an orchestral Walt Whitman Overture in 1899.[4] While on tour with the Carl Rosa company Holst had read some of Max Müller's books, which inspired in him a keen interest in Sanskrit texts, particularly the Rig Veda hymns.[59] He found the existing English versions of the texts unconvincing,[n 9] and decided to make his own translations, despite his lack of skills as a linguist. He enrolled in 1909 at University College, London, to study the language.[60]

Imogen commented on his translations: "He was not a poet, and there are occasions when his verses seem naïve. But they never sound vague or slovenly, for he had set himself the task of finding words that would be 'clear and dignified' and that would 'lead the listener into another world'".[61] His settings of translations of Sanskrit texts included Sita (1899–1906), a three-act opera based on an episode in the Ramayana (which he eventually entered for a competition for English opera set by the Milan music publisher Tito Ricordi);[62] Savitri (1908), a chamber opera based on a tale from the Mahabharata; four groups of Hymns from the Rig Veda (1908–14); and two texts originally by Kālidāsa: Two Eastern Pictures (1909–10) and The Cloud Messenger (1913).[4]

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, British musical circles had experienced a new interest in national folk music. Some composers, such as Sullivan and Elgar, remained indifferent,[63] but Parry, Stanford, Stainer and Alexander Mackenzie were founding members of the Folk-Song Society.[64] Parry considered that by recovering English folk song, English composers would find an authentic national voice; he commented, "in true folk-songs there is no sham, no got-up glitter, and no vulgarity".[64] Vaughan Williams was an early and enthusiastic convert to this cause, going round the English countryside collecting and noting down folk songs. These had an influence on Holst. Though not as passionate on the subject as his friend, he incorporated a number of folk melodies in his own compositions and made several arrangements of folk songs collected by others.[64] The Somerset Rhapsody (1906–07), was written at the suggestion of the folk-song collector Cecil Sharp and made use of tunes that Sharp had noted down. Holst described its performance at the Queen's Hall in 1910 as "my first real success".[65] A few years later Holst became excited by another musical renaissance—the rediscovery of English madrigal composers. Weelkes was his favourite of all the Tudor composers, but Byrd also meant much to him.[66]

Holst was a keen rambler. He walked extensively in England, Italy, France and Algeria. In 1908 he travelled to Algeria on medical advice as a treatment for asthma and the depression that he suffered after his opera Sita failed to win the Ricordi prize.[67] This trip inspired the suite Beni Mora, which incorporated music he heard in the Algerian streets.[68] Vaughan Williams wrote of this exotic work, "if it had been played in Paris rather than London it would have given its composer a European reputation, and played in Italy would probably have caused a riot."[69]

1910s

In June 1911 Holst and his Morley College students gave the first performance since the seventeenth century of Purcell's The Fairy-Queen. The full score had been lost soon after Purcell's death in 1695, and had only recently been found. Twenty-eight Morley students copied out the complete vocal and orchestral parts. There were 1,500 pages of music and it took the students almost eighteen months to copy them out in their spare time.[70] A concert performance of the work was given at The Old Vic, preceded by an introductory talk by Vaughan Williams. The Times praised Holst and his forces for "a most interesting and artistic performance of this very important work".[71]

After this success, Holst was disappointed the following year by the lukewarm reception of his choral work The Cloud Messenger. He again went travelling, accepting an invitation from H. Balfour Gardiner to join him and the brothers Clifford and Arnold Bax in Spain.[72] During this holiday Clifford Bax introduced Holst to astrology, an interest that later inspired his suite The Planets. Holst cast his friends' horoscopes for the rest of his life and referred to astrology as his "pet vice".[73]

In 1913, St Paul's Girls' School opened a new music wing, and Holst composed St Paul's Suite for the occasion. The new building contained a sound-proof room, handsomely equipped, where he could work undisturbed.[74] Holst and his family moved to a house in Brook Green, very close to the school. For the previous six years they had lived in a pretty house overlooking the Thames at Barnes, but the river air, frequently foggy, affected his breathing.[75] For use at weekends and during school holidays, Holst and his wife bought a cottage in Thaxted, Essex, surrounded by mediaeval buildings and ample rambling opportunities.[76] In 1917 they moved to a house in the centre of the town, where they stayed until 1925.[77]

At Thaxted, Holst became friendly with the Rev Conrad Noel, known as the "Red Vicar", who supported the Independent Labour Party and espoused many causes unpopular with conservative opinion.[78] Noel also encouraged the revival of folk-dancing and processionals as part of church ceremonies, innovations which caused controversy among traditionally-minded churchgoers.[79] Holst became an occasional organist and choirmaster at Thaxted Parish Church; he also developed an interest in bell-ringing.[n 10] He started an annual music festival at Whitsuntide in 1916; students from Morley College and St Paul's Girls' School performed together with local participants.[81]

Holst's a cappella carol, "This Have I Done For My True Love", was dedicated to Noel in recognition of his interest in the ancient origins of religion (the composer always referred to the work as "The Dancing Day").[82] It received its first performance during the Third Whitsun Festival at Thaxted in May 1918. During that festival, Noel, a staunch supporter of Russia's October Revolution, demanded in a Saturday message during the service that there should be a greater political commitment from those who participated in the church activities; his claim that several of Holst's pupils (implicitly those from St Paul's Girls' School) were merely "camp followers" caused offence.[83] Holst, anxious to protect his students from being embroiled in ecclesiastical conflict, moved the Whitsun Festival to Dulwich, though he himself continued to help with the Thaxted choir and to play the church organ on occasion.[84]

First World War

At the outbreak of the First World War, Holst tried to enlist but was rejected as unfit for military service.[9] He felt frustrated that he could not contribute to the war effort. His wife became a volunteer ambulance driver; Vaughan Williams went on active service to France as did Holst's brother Emil; Holst's friends the composers George Butterworth and Cecil Coles were killed in battle.[85] He continued to teach and compose; he worked on The Planets and prepared his chamber opera Savitri for performance. It was first given in December 1916 by students of the London School of Opera at the Wellington Hall in St John's Wood.[86] It attracted no attention at the time from the main newspapers, though when professionally staged five years later it was greeted as "a perfect little masterpiece."[87] In 1917 he wrote The Hymn of Jesus for chorus and orchestra, a work which remained unperformed until after the war.[4]

In 1918, as the war neared its end, Holst finally had the prospect of a job that offered him the chance to serve. The music section of the YMCA's education department needed volunteers to work with British troops stationed in Europe awaiting demobilisation.[88] Morley College and St Paul's Girls' School offered him a year's leave of absence, but there remained one obstacle: the YMCA felt that his surname looked too German to be acceptable in such a role.[6] He formally changed "von Holst" to "Holst" by deed poll in September 1918.[89] He was appointed as the YMCA's musical organiser for the Near East, based in Salonica.[90]

Holst was given a spectacular send-off. The conductor Adrian Boult recalled, "Just before the Armistice, Gustav Holst burst into my office: 'Adrian, the YMCA are sending me to Salonica quite soon and Balfour Gardiner, bless his heart, has given me a parting present consisting of the Queen's Hall, full of the Queen's Hall Orchestra for the whole of a Sunday morning. So we're going to do The Planets, and you've got to conduct'."[91] There was a burst of activity to get things ready in time. The girls at St Paul's helped to copy out the orchestral parts,[91] and the women of Morley and the St Paul's girls learned the choral part in the last movement.[92]

The performance was given on 29 September to an invited audience including Sir Henry Wood and most of the professional musicians in London.[93] Five months later, when Holst was in Greece, Boult introduced The Planets to the general public, at a concert in February 1919; Holst sent him a long letter full of suggestions,[n 11] but failed to convince him that the suite should be played in full. The conductor believed that about half an hour of such radically new music was all the public could absorb at first hearing, and he gave only five of the seven movements on that occasion.[95]

Holst enjoyed his time in Salonica, from where he was able to visit Athens, which greatly impressed him.[96] His musical duties were wide-ranging, and even obliged him on occasion to play the violin in the local orchestra: "it was great fun, but I fear I was not of much use".[96] He returned to England in June 1919.[97]

Post-war

On his return from Greece, Holst resumed his teaching and composing. In addition to his existing work he accepted a lectureship in composition at the University of Reading and joined Vaughan Williams in teaching composition at their alma mater the RCM.[64] Inspired by Adrian Boult's conducting classes at the RCM, Holst tried to further pioneer music education for women by proposing to the High Mistress of St Paul's Girls' School that he should invite Boult to give classes at the school: "It would be glorious if the SPGS turned out the only women conductors in the world!"[98] In his soundproof room at SPGS he composed the Ode to Death, a setting of a poem by Whitman, which according to Vaughan Williams is considered by many to be Holst's most beautiful choral work.[35]

Holst, in his forties, suddenly found himself in demand. The New York Philharmonic and Chicago Symphony Orchestra vied to be the first to play The Planets in the US.[64] The success of that work was followed in 1920 by an enthusiastic reception for The Hymn of Jesus, described in The Observer as "one of the most brilliant and one of the most sincere pieces of choral and orchestral expression heard for some years."[99] The Times called it "undoubtedly the most strikingly original choral work which has been produced in this country for many years."[100]

To his surprise and dismay Holst was becoming famous.[35] Celebrity was something wholly foreign to his nature. As the music scholar Byron Adams puts it, "he struggled for the rest of his life to extricate himself from the web of garish publicity, public incomprehension and professional envy woven about him by this unsought-for success."[101] He turned down honours and awards proffered to him,[n 12] and refused to grant interviews or sign autographs.[64]

Holst's comic opera The Perfect Fool (1923) was widely seen as a satire of Parsifal, though Holst firmly denied it.[102] The piece, with Maggie Teyte in the leading soprano role and Eugene Goossens conducting, was enthusiastically received at its premiere in the Royal Opera House.[103] At a concert in Reading in 1923, Holst slipped and fell, suffering concussion. He seemed to make a good recovery, and he felt up to accepting an invitation to the US, lecturing and conducting at the University of Michigan.[104] After he returned he found himself more and more in demand, to conduct, prepare his earlier works for publication, and, as before, to teach. The strain caused by these demands on him was too great; on doctor's orders he cancelled all professional engagements during 1924, and retreated to Thaxted.[105] In 1925 he resumed his work at St Paul's Girls' School, but did not return to any of his other posts.[106]

Later years

Holst's productivity as a composer benefited almost at once from his release from other work. His works from this period include the Choral Symphony to words by Keats (a Second Choral Symphony to words by George Meredith exists only in fragments). A short Shakespearian opera, At the Boar's Head, followed; neither had the immediate popular appeal of A Moorside Suite for brass band of 1928.[107]

In 1927 Holst was commissioned by the New York Symphony Orchestra to write a symphony. Instead, he wrote an orchestral piece Egdon Heath, inspired by Thomas Hardy's Wessex. It was first performed in February 1928, a month after Hardy's death, at a memorial concert. By this time the public's brief enthusiasm for everything Holstian was waning,[106] and the piece was not well received in New York. Olin Downes in The New York Times opined that "the new score seemed long and undistinguished".[108] The day after the American performance, Holst conducted the City of Birmingham Orchestra in the British premiere. The Times acknowledged the bleakness of the work but allowed that it matched Hardy's grim view of the world: "Egdon Heath is not likely to be popular, but it says what the composer wants to say, whether we like it or not, and truth is one aspect of duty."[109] Holst had been distressed by hostile reviews of some of his earlier works, but he was indifferent to critical opinion of Egdon Heath, which he regarded as, in Adams's phrase, his "most perfectly realized composition".[110]

Towards the end of his life Holst wrote the Choral Fantasia (1930) and he was commissioned by the BBC to write a piece for military band; the resulting prelude and scherzo Hammersmith was a tribute to the place where he had spent most of his life. The composer and critic Colin Matthews considers the work "as uncompromising in its way as Egdon Heath, discovering, in the words of Imogen Holst, 'in the middle of an over-crowded London ... the same tranquillity that he had found in the solitude of Egdon Heath'".[4] The work was unlucky in being premiered at a concert that also featured the London premiere of Walton's Belshazzar's Feast, by which it was somewhat overshadowed.[111]

Holst wrote a score for a British film, The Bells (1931), and was amused to be recruited as an extra in a crowd scene.[112] Both film and score are now lost.[113] He wrote a "jazz band piece" that Imogen later arranged for orchestra as Capriccio.[114] Having composed operas throughout his life with varying success, Holst found for his last opera, The Wandering Scholar, what Matthews calls "the right medium for his oblique sense of humour, writing with economy and directness".[4]

Harvard University offered Holst a lectureship for the first six months of 1932. Arriving via New York he was pleased to be reunited with his brother, Emil, whose acting career under the name of Ernest Cossart had taken him to Broadway; but Holst was dismayed by the continual attentions of press interviewers and photographers. He enjoyed his time at Harvard, but was taken ill while there: a duodenal ulcer prostrated him for some weeks. He returned to England, joined briefly by his brother for a holiday together in the Cotswolds.[115] His health declined, and he withdrew further from musical activities. One of his last efforts was to guide the young players of the St Paul's Girls' School orchestra through one of his final compositions, the Brook Green Suite, in March 1934.[116]

Holst died in London on 25 May 1934, at the age of 59, of heart failure following an operation on his ulcer.[4] His ashes were interred at Chichester Cathedral in Sussex, close to the memorial to Thomas Weelkes, his favourite Tudor composer.[117] Bishop George Bell gave the memorial oration at the funeral, and Vaughan Williams conducted music by Holst and himself.[118]

Music

Style

Holst's absorption of folksong, not only in the melodic sense but in terms of its simplicity and economy of expression,[119] helped to develop a style that many of his contemporaries, even admirers, found austere and cerebral.[120][121] This is contrary to the popular identification of Holst with The Planets, which Matthews believes has masked his status as a composer of genuine originality.[4] Against charges of coldness in the music, Imogen cites Holst's characteristic "sweeping modal tunes mov[ing] reassuringly above the steps of a descending bass",[120] while Michael Kennedy points to the 12 Humbert Wolfe settings of 1929, and the 12 Welsh folksong settings for unaccompanied chorus of 1930–31, as works of true warmth.[121]

Many of the characteristics that Holst employed — unconventional time signatures, rising and falling scales, ostinato, bitonality and occasional polytonality — set him apart from other English composers.[4] Vaughan Williams remarked that Holst always said in his music what he wished to say, directly and concisely; "He was not afraid of being obvious when the occasion demanded, nor did he hesitate to be remote when remoteness expressed his purpose".[122] Kennedy has surmised that Holst's economy of style was in part a product of the composer's poor health: "the effort of writing it down compelled an artistic economy which some felt was carried too far".[121] However, as an experienced instrumentalist and orchestra member, Holst understood music from the standpoint of his players and made sure that, however challenging, their parts were always practicable.[123] According to his pupil Jane Joseph, Holst fostered in performance "a spirit of practical comradeship ... none could know better than he the boredom possible to a professional player, and the music that rendered boredom impossible".[124]

Early works

Although Holst wrote many works—particularly songs—during his student days and early adulthood, almost everything he wrote before 1904 he later classified as derivative "early horrors".[4][125] Nevertheless, the composer and critic Colin Matthews recognises even in these apprentice works an "instinctive orchestral flair".[4] Of the few pieces from this period which demonstrate some originality, Matthews pinpoints the G minor String Trio of 1894 (unperformed until 1974) as the first underivative work produced by Holst.[126] Matthews and Imogen Holst each highlight the "Elegy" movement in The Cotswold Symphony (1899–1900) as among the more accomplished of the apprentice works, and Imogen discerns glimpses of her father's real self in the 1899 Suite de ballet and the Ave Maria of 1900. She and Matthews have asserted that Holst found his genuine voice in his setting of Whitman's verses, The Mystic Trumpeter (1904), in which the trumpet calls that characterise Mars in The Planets are briefly anticipated.[4][125] In this work, Holst first employs the technique of bitonality—the use of two keys simultaneously.[9]

Experimental years

At the beginning of the 20th century, according to Matthews, it appeared that Holst might follow Schoenberg into late Romanticism. Instead, as Holst recognised afterwards, his encounter with Purcell's Dido and Aeneas prompted his searching for a "musical idiom of the English language";[37] the folksong revival became a further catalyst for Holst to seek inspiration from other sources during the first decade or so of the new century.[4]

Indian period

Holst's interest in Indian mythology, shared by many of his contemporaries, first became musically evident in the opera Sita (1901–06).[127] During the opera's long gestation, Holst worked on other Indian-themed pieces. These included Maya (1901) for violin and piano, regarded by the composer and writer Raymond Head as "an insipid salon-piece whose musical language is dangerously close to Stephen Adams".[127][n 13] Then, through Vaughan Williams, Holst discovered and became an admirer of the music of Ravel,[129] whom he considered a "model of purity" on the level with Haydn,[130] another composer he greatly admired.[131]

The combined influence of Ravel, Hindu spiritualism and English folk tunes[129] enabled Holst to get beyond the once all-consuming influences of Wagner and Richard Strauss and to forge his own style. Imogen Holst has acknowledged Holst's own suggestion (written to Vaughan Williams): "[O]ne ought to follow Wagner until he leads you to fresh things". She notes that although much of his grand opera, Sita, is "'good old Wagnerian bawling' ... towards the end a change comes over the music, and the beautifully calm phrases of the hidden chorus representing the Voice of the Earth are in Holst's own language."[132]

According to Rubbra, the publication in 1911 of Holst's Rig Veda Hymns was a landmark event in the composer's development: "Before this, Holst's music had, indeed, shown the clarity of utterance which has always been his characteristic, but harmonically there was little to single him out as an important figure in modern music."[59] Dickinson describes these vedic settings as pictorial rather than religious; although the quality is variable the sacred texts clearly "touched vital springs in the composer's imagination".[133] While the music of Holst's Indian verse settings remained generally western in character, in some of the vedic settings he experimented with Indian raga (scales).[134]

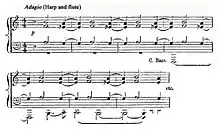

The chamber opera Savitri (1908) is written for three solo voices, a small hidden female chorus, and an instrumental combination of two flutes, a cor anglais and a double string quartet.[135] The music critic John Warrack comments on the "extraordinary expressive subtlety" with which Holst deploys the sparse forces: "... [T]he two unaccompanied vocal lines opening the work skilfully convey the relationship between Death, steadily advancing through the forest, and Savitri, her frightened answers fluttering round him, unable to escape his harmonic pull."[9] Head describes the work as unique in its time for its compact intimacy, and considers it Holst's most successful attempt to end the domination of Wagnerian chromaticism in his music.[135] Dickinson considers it a significant step, "not towards opera, but towards an idiomatic pursuit of [Holst's] vision".[136] Of the Kālidāsa texts, Dickinson dismisses The Cloud Messenger (1910–12) as an "accumulation of desultory incidents, opportunistic dramatic episodes and ecstatic outpourings" which illustrate the composer's creative confusion during that period; the Two Eastern Pictures (1911), in Dickinson's view, provide "a more memorable final impression of Kālidāsa".[136]

Folksong and other influences

Holst's settings of Indian texts formed only a part of his compositional output in the period 1900 to 1914. A highly significant factor in his musical development was the English folksong revival, evident in the orchestral suite A Somerset Rhapsody (1906–07), a work that was originally to be based around eleven folksong themes; this was later reduced to four.[137] Observing the work's kinship with Vaughan Williams's Norfolk Rhapsody, Dickinson remarks that, with its firm overall structure, Holst's composition "rises beyond the level of ... a song-selection".[138] Imogen acknowledges that Holst's discovery of English folksongs "transformed his orchestral writing", and that the composition of A Somerset Rhapsody did much to banish the chromaticisms that had dominated his early compositions.[125] In the Two Songs without Words of 1906, Holst showed that he could create his own original music using the folk idiom.[139] An orchestral folksong fantasy Songs of the West, also written in 1906, was withdrawn by the composer and never published, although it emerged in the 1980s in the form of an arrangement for wind band by James Curnow.[140]

In the years before the First World War, Holst composed in a variety of genres. Matthews considers the evocation of a North African town in the Beni Mora suite of 1908 the composer's most individual work to that date; the third movement gives a preview of minimalism in its constant repetition of a four-bar theme. Holst wrote two suites for military band, in E flat (1909) and F major (1911) respectively, the first of which became and remains a brass-band staple.[4] This piece, a highly original and substantial musical work, was a signal departure from what Short describes as "the usual transcriptions and operatic selections which pervaded the band repertoire".[141] Also in 1911 he wrote Hecuba's Lament, a setting of Gilbert Murray's translation from Euripides built on a seven-beat refrain designed, says Dickinson, to represent Hecuba's defiance of divine wrath.[142] In 1912 Holst composed two psalm settings, in which he experimented with plainsong;[143] the same year saw the enduringly popular St Paul's Suite (a "gay but retrogressive" piece according to Dickinson),[144] and the failure of his large scale orchestral work Phantastes.[4]

The Planets

Holst conceived the idea of The Planets in 1913, partly as a result of his interest in astrology,[n 14] and also from his determination, despite the failure of Phantastes, to produce a large-scale orchestral work.[9] The chosen format may have been influenced by Schoenberg's Fünf Orchesterstücke, and shares something of the aesthetic, Matthews suggests, of Debussy's Nocturnes or La mer.[4][146] Holst began composing The Planets in 1914; the movements appeared not quite in their final sequence; "Mars" was the first to be written, followed by "Venus" and "Jupiter". "Saturn", "Uranus" and "Neptune" were all composed during 1915, and "Mercury" was completed in 1916.[4]

Each planet is represented with a distinct character; Dickinson observes that "no planet borrows colour from another".[147] In "Mars", a persistent, uneven rhythmic cell consisting of five beats, combined with trumpet calls and harmonic dissonance provides battle music which Short asserts is unique in its expression of violence and sheer terror, "... Holst's intention being to portray the reality of warfare rather than to glorify deeds of heroism".[148] In "Venus", Holst incorporated music from an abandoned vocal work, A Vigil of Pentecost, to provide the opening; the prevalent mood within the movement is of peaceful resignation and nostalgia.[126][149] "Mercury" is dominated by uneven metres and rapid changes of theme, to represent the speedy flight of the winged messenger.[150] "Jupiter" is renowned for its central melody, "Thaxted", in Dickinson's view "a fantastic relaxation in which many retain a far from sneaking delight".[151] Dickinson and other critics have decried the later use of the tune in the patriotic hymn "I Vow to Thee, My Country"—despite Holst's full complicity.[9][151][n 15]

For "Saturn", Holst again used a previously-composed vocal piece, Dirge and Hymeneal, as the basis for the movement, where repeated chords represent the relentless approach of old age.[152] "Uranus", which follows, has elements of Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique and Dukas's The Sorcerer's Apprentice, in its depiction of the magician who "disappears in a whiff of smoke as the sonic impetus of the movement diminishes from fff to ppp in the space of a few bars".[153] "Neptune", the final movement, concludes with a wordless female chorus gradually receding, an effect which Warrack likens to "unresolved timelessness ... never ending, since space does not end, but drifting away into eternal silence".[9] Apart from his concession with "I Vow to Thee..."', Holst insisted on the unity of the whole work, and opposed the performance of individual movements.[9] Nevertheless, Imogen wrote that the piece had "suffered from being quoted in snippets as background music".[154]

Maturity

During and after the composition of The Planets, Holst wrote or arranged numerous vocal and choral works, many of them for the wartime Thaxted Whitsun Festivals, 1916–18. They include the Six Choral Folksongs of 1916, based on West Country tunes, of which "Swansea Town", with its "sophisticated tone", is deemed by Dickinson to be the most memorable.[155] Holst downplayed such music as "a limited form of art" in which "mannerisms are almost inevitable";[156] the composer Alan Gibbs, however, believes Holst's set at least equal to Vaughan Williams's Five English Folk Songs of 1913.[157]

Holst's first major work after The Planets was the Hymn of Jesus, completed in 1917. The words are from a Gnostic text, the apocryphal Acts of John, using a translation from the Greek which Holst prepared with assistance from Clifford Bax and Jane Joseph.[158] Head comments on the innovative character of the Hymn: "At a stroke Holst had cast aside the Victorian and Edwardian sentimental oratorio, and created the precursor of the kind of works that John Tavener, for example, was to write in the 1970s".[159] Matthews has written that the Hymn's "ecstatic" quality is matched in English music "perhaps only by Tippett's The Vision of Saint Augustine";[4] the musical elements include plainsong, two choirs distanced from each other to emphasise dialogue, dance episodes and "explosive chordal dislocations".[159]

In the Ode to Death (1918–19), the quiet, resigned mood is seen by Matthews as an "abrupt volte-face" after the life-enhancing spirituality of the Hymn.[4] Warrack refers to its aloof tranquillity;[9] Imogen Holst believed the Ode expressed Holst's private attitude to death.[154] The piece has rarely been performed since its premiere in 1922, although the composer Ernest Walker thought it was Holst's finest work to that date.[160]

The influential critic Ernest Newman considered The Perfect Fool "the best of modern British operas",[161] but its unusually short length (about an hour) and parodic, whimsical nature—described by The Times as "a brilliant puzzle"—put it outside the operatic mainstream.[103] Only the ballet music from the opera, which The Times called "the most brilliant thing in a work glittering with brilliant moments", has been regularly performed since 1923.[162] Holst's libretto attracted much criticism, although Edwin Evans remarked on the rare treat in opera of being able to hear the words being sung.[163]

Later works

Before his enforced rest in 1924, Holst demonstrated a new interest in counterpoint, in his Fugal Overture of 1922 for full orchestra and the neo-classical Fugal Concerto of 1923, for flute, oboe and strings.[4] In his final decade he mixed song settings and minor pieces with major works and occasional new departures; the 1925 Terzetto for flute, violin and oboe, each instrument playing in a different key, is cited by Imogen as Holst's only successful chamber work.[164] Of the Choral Symphony completed in 1924, Matthews writes that, after several movements of real quality, the finale is a rambling anticlimax.[4] Holst's penultimate opera, At the Boar's Head (1924), is based on tavern scenes from Shakespeare's Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2. The music, which is largely derived from old English melodies gleaned from Cecil Sharp and other collections, has pace and verve;[4] the contemporary critic Harvey Grace discounted the lack of originality, a facet which he said "can be shown no less convincingly by a composer's handling of material than by its invention".[165]

Egdon Heath (1927) was Holst's first major orchestral work after The Planets. Matthews summarises the music as "elusive and unpredictable [with] three main elements: a pulseless wandering melody [for strings], a sad brass processional, and restless music for strings and oboe." The mysterious dance towards the end is, says Matthews, "the strangest moment in a strange work".[4] Richard Greene in Music & Letters describes the piece as "a larghetto dance in a siciliano rhythm with a simple, stepwise, rocking melody", but lacking the power of The Planets and, at times, monotonous to the listener.[166] A more popular success was A Moorside Suite for brass band, written as a test piece for the National Brass Band Festival championships of 1928. While written within the traditions of north-country brass-band music, the suite, Short says, bears Holst's unmistakable imprint, "from the skipping 6/8 of the opening Scherzo, to the vigorous melodic fourths of the concluding March, the intervening Nocturne bearing a family resemblance to the slow-moving procession of Saturn".[167] A Moorside Suite has undergone major revisionism in the article "Symphony Within: rehearing Holst's A Moorside Suite" by Stephen Arthur Allen in the Winter 2017 edition of The Musical Times.[168] As with Egdon Heath – commissioned as a symphony – the article reveals the symphonic nature of this brass-band work.

After this, Holst tackled his final attempt at opera in a cheerful vein, with The Wandering Scholar (1929–30), to a text by Clifford Bax. Imogen refers to the music as "Holst at his best in a scherzando (playful) frame of mind";[120] Vaughan Williams commented on the lively, folksy rhythms: "Do you think there's a little bit too much 6/8 in the opera?"[169] Short observes that the opening motif makes several reappearances without being identified with a particular character, but imposes musical unity on the work.[170]

Holst composed few large-scale works in his final years. A Choral Fantasia of 1930 was written for the Three Choirs Festival at Gloucester; beginning and ending with a soprano soloist, the work, also involving chorus, strings, brass and percussion, includes a substantial organ solo which, says Imogen Holst, "knows something of the 'colossal and mysterious' loneliness of Egdon Heath".[171] Apart from his final uncompleted symphony, Holst's remaining works were for small forces; the eight Canons of 1932 were dedicated to his pupils, though in Imogen's view that they present a formidable challenge to the most professional of singers. The Brook Green Suite (1932), written for the orchestra of St Paul's School, was a late companion piece to the St Paul's Suite.[154] The Lyric Movement for viola and small orchestra (1933) was written for Lionel Tertis. Quiet and contemplative, and requiring little virtuosity from the soloist, the piece was slow to gain popularity among violists.[172] Robin Hull, in Penguin Music Magazine, praised the work's "clear beauty—impossible to mistake for the art of any other composer"; in Dickinson's view, however, it remains "a frail creation".[173] Holst's final composition, the orchestral scherzo movement of a projected symphony, contains features characteristic of much of Holst's earlier music—"a summing up of Holst's orchestral art", according to Short.[174] Dickinson suggests that the somewhat casual collection of material in the work gives little indication of the symphony that might have been written.[175]

Recordings

Holst made some recordings, conducting his own music. For the Columbia company he recorded Beni Mora, the Marching Song and the complete Planets with the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) in 1922, using the acoustic process. The limitations of early recording prevented the gradual fade-out of women's voices at the end of "Neptune", and the lower strings had to be replaced by a tuba to obtain an effective bass sound.[176] With an anonymous string orchestra Holst recorded the St Paul's Suite and Country Song in 1925.[177] Columbia's main rival, HMV, issued recordings of some of the same repertoire, with an unnamed orchestra conducted by Albert Coates.[178] When electrical recording came in, with dramatically improved recording quality, Holst and the LSO re-recorded The Planets for Columbia in 1926.[179]

In the early LP era little of Holst's music was available on disc. Only six of his works are listed in the 1955 issue of The Record Guide: The Planets (recordings under Boult on HMV and Nixa, and another under Sir Malcolm Sargent on Decca); the Perfect Fool ballet music; the St Paul's Suite; and three short choral pieces.[180] In the stereo LP and CD eras numerous recordings of The Planets were issued, performed by orchestras and conductors from round the world. By the early years of the 21st century most of the major and many of the minor orchestral and choral works had been issued on disc. The 2008 issue of The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music contained seven pages of listings of Holst's works on CD.[181] Of the operas, Savitri, The Wandering Scholar, and At the Boar's Head have been recorded.[182]

Legacy

A tribute from Edmund Rubbra[183]

Warrack emphasises that Holst acquired an instinctive understanding—perhaps more so than any English composer—of the importance of folksong. In it he found "a new concept not only of how melody might be organized, but of what the implications were for the development of a mature artistic language".[9] Holst did not found or lead a school of composition; nevertheless, he exercised influences over both contemporaries and successors. According to Short, Vaughan Williams described Holst as "the greatest influence on my music",[123] although Matthews asserts that each influenced the other equally.[4] Among later composers, Michael Tippett is acknowledged by Short as Holst's "most significant artistic successor", both in terms of compositional style and because Tippett, who succeeded Holst as director of music at Morley College, maintained the spirit of Holst's music there.[123] Of an early encounter with Holst, Tippett later wrote: "Holst seemed to look right inside me, with an acute spiritual vision".[184] Kennedy observes that "a new generation of listeners ... recognized in Holst the fount of much that they admired in the music of Britten and Tippett".[121] Holst's pupil Edmund Rubbra acknowledged how he and other younger English composers had adopted Holst's economy of style: "With what enthusiasm did we pare down our music to the very bone".[120]

Short cites other English composers who are in debt to Holst, in particular William Walton and Benjamin Britten, and suggests that Holst's influence may have been felt further afield.[n 16] Above all, Short recognises Holst as a composer for the people, who believed it was a composer's duty to provide music for practical purposes—festivals, celebrations, ceremonies, Christmas carols or simple hymn tunes. Thus, says Short, "many people who may never have heard any of [Holst's] major works ... have nevertheless derived great pleasure from hearing or singing such small masterpieces as the carol 'In the Bleak Midwinter'".[186]

On 27 September 2009, after a weekend of concerts at Chichester Cathedral in memory of Holst, a new memorial was unveiled to mark the 75th anniversary of the composer's death. It is inscribed with words from the text of The Hymn of Jesus: "The heavenly spheres make music for us".[187] In April 2011 a BBC television documentary, Holst: In the Bleak Midwinter, charted Holst's life with particular reference to his support for socialism and the cause of working people.[188]

Notes and references

Notes

- Clara had a Spanish great-grandmother, who eloped and lived with an Irish peer; Imogen Holst speculates whether this family scandal may have mitigated the Lediard family's disapproval of Clara's marrying a musician.[1]

- Imogen Holst records, "A second cousin in the eighteenth century had been honoured by the German Emperor for a neat piece of work in international diplomacy, and the unscrupulous Matthias had calmly borrowed the 'von' in the hopes that it might bring in a few more piano pupils."[6]

- Adolph moved the family from 4 Pittville Terrace (named today Clarence Road) to 1 Vittoria Walk.[9][10]

- Ralph Vaughan Williams quoted Gilbert and Sullivan's H.M.S. Pinafore in characterising Holst: "'in spite of all temptations [to belong to other nations]', which his name may suggest, Holst 'remains an Englishman'"[17]

- According to Imogen Holst the most probable lender was Adolph's sister Nina.[24]

- Case was instrumental in having Beethoven's Three Equals for four trombones, WoO 30 played at W. E. Gladstone's funeral in May 1898.[26]

- Vaughan Williams recorded this in a letter dated 19 September 1937 to Imogen Holst, signing himself, as was his custom, "Uncle Ralph". In the same letter he wrote of Holst's view "That the artist is born again & starts afresh with every new work."[41]

- Imogen Holst recounts an occasion when Holst was persuaded to relax his teetotalism. Fuelled by a single glass of champagne he played on his trombone the piccolo part during a waltz, to Wurm's astonishment and admiration.[38]

- Holst considered them either "misleading translations in colloquial English" or else "strings of English words with no meanings to an English mind."[60]

- In 2013, Simon Gay and Mark Davies reported in the publication The Ringing World that Holst was interested in change ringing and "might have turned his compositional talents in that direction". When searching the Holst archives they discovered two peal compositions "which show Holst was remarkably far ahead of his time from the ringing point of view". The compositions had not, at April 2013, yet been rung.[80]

- In the letter, sent according to Holst from "Piccadilly Circus, Salonica", one suggestion read, "Mars. You made it wonderfully clear ... now could you make more row? And work up more sense of climax? Perhaps hurry certain bits? Anyhow, it must sound more unpleasant and far more terrifying".[94]

- The two exceptions Holst made to this rule were Yale University's Howland Memorial Prize (1924) and the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society (1930).[9]

- "Stephen Adams" was the assumed name of Michael Maybrick, a British composer of Victorian sentimental ballads, the best known of which is "The Holy City".[128]

- Holst was reading Alan Leo's booklet What is a Horoscope? at the time [145]

- Alan Gibbs, who edited Dickinson's book, remarks in a footnote that, perhaps fortunately, neither Dickinson nor Imogen was alive to hear the "deplorable 1990s version" of the Jupiter tune, sung as an anthem at the Rugby World Cup.[151]

- Short observes that the rising fourths of "Jupiter" can be heard in Copland's Appalachian Spring, and suggests that the Hymn of Jesus might be considered as a forerunner of Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms "and the hieratic serial cantatas", though admitting that "it is doubtful whether Stravinsky was familiar with, or even aware of this work".[185]

References

- Holst (1969), p. 6.

- Mitchell (2001), p. 3

- Mitchell (2001), p. 2

- Matthews, Colin. "Holst, Gustav". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 22 March 2013. (subscription required)

- Short (1990), p. 9

- Holst (1969), p. 52

- Short (1990), p. 10

- Short (1990), p. 476; "The Theatres", The Times, 16 May 1929, p. 1; Atkinson, Brooks. "Over the Coffee Cups", The New York Times, 5 April 1932 (subscription required); and Jones, Idwal. "Buttling a Way to Fame", The New York Times, 7 November 1937 (subscription required)

- Warrack, John (January 2011). "Holst, Gustav Theodore". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online edition. Retrieved 4 April 2013. (subscription required)

- Short (1990), p. 11.

- Mitchell (2001), pp. 3–4

- Dickinson (1957), p. 135.

- Holst (1969), p. 7

- "Mr Gustav Holst". The Times. 26 May 1934. p. 7.

- Holst (1981), p. 15.

- Mitchell (2001), p. 5 and Holst (1969), p. 23

- Vaughan Williams, Ralph (July 1920). "Gustav Holst, I". Music & Letters. 1 (3): 181–90. doi:10.1093/ml/1.3.181. JSTOR 725903. (subscription required)

- Holst (1969), p. 9.

- Holst (1969), p. 20.

- Short (1990), p. 16.

- Mitchell (2001), p. 6

- Holst (1981), p. 17.

- Short (1990), pp. 17–18.

- Holst (1969), p. 8

- Holst (1969), pp. 13, 15.

- Mansfield, Orlando A. (April 1916). "Some Anomalies in Orchestral Accompaniments to Church Music". The Musical Quarterly. Oxford University Press. 2 (2). doi:10.1093/mq/II.2.199. JSTOR 737953.(subscription required)

- Mitchell (2001), p. 9.

- Holst (1981), p. 19

- Holst (1969), p. 11.

- Holst (1969), pp. 23, 41; and Short (1990), p. 41

- Rodmell (2002), p. 49.

- Howells, Herbert. "Charles Villiers Stanford (1852–1924). An Address at His Centenary". Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, 79th Sess. (1952–1953): 19–31. JSTOR 766209. (subscription required)

- Mitchell (2001), p. 15.

- Moore (1992), p. 26.

- Vaughan Williams, Ralph. "Holst, Gustav Theodore (1874–1934)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online edition. Retrieved 22 March 2013. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- de Val, Dorothy (2013). In Search of Song: The Life and Times of Lucy Broadwood. Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Ashgate Publishing. p. 66.

- Holst, G. (1974), p. 23

- Holst (1969), p. 16

- Holst (1969), p. 17.

- Holst (1981), p. 21.

- Vaughan Williams (2008), p. 252.

- Holst (1981), p. 23

- Holst (1981), p. 60.

- "The Hospital for Women". The Times. 26 May 1897. p. 12.

- Short (1990), p. 34.

- Holst (1981), p. 27

- Short (1990), p. 28.

- Holst (1969), p. 15.

- Holst (1981), p. 28.

- Holst (1969), p. 29.

- Dickinson (1957), p. 37.

- Holst (1969), p. 24.

- Holst (1981), p. 30.

- Gibbs (2000), pp. 161–62.

- Gibbs (2000), p. 168.

- Holst (1969), p. 30.

- Rubbra & Lloyd (1974), p. 40.

- Rubbra & Lloyd (1974), p. 41.

- Rubbra & Lloyd (1974), p. 30

- Holst (1981), p. 24

- Holst (1981), p. 25

- Short (1990), p. 55.

- Hughes (1960), p. 159; and Kennedy (1970), p. 10

- Graebe, Martin (2011). "Gustav Holst, Songs of the West, and the English Folk Song Movement". Folk Music Journal. 10 (1): 5–41. (subscription required)

- Short (1990), p. 88.

- Short (1990), p. 207.

- Short (1990), pp. 74–75.

- Mitchell (2001), p. 91.

- Vaughan Williams, Ralph (October 1920). "Gustav Holst (Continued)". Music & Letters. 1 (4): 305–317. doi:10.1093/ml/1.4.305. JSTOR 726997. (subscription required)

- Holst (1981), pp. 30–31.

- "Music—Purcell's 'Fairy Queen'". The Times. 12 June 1911. p. 10.

- Mitchell (2001), p. 118.

- Holst (1969), p. 43.

- Mitchell (2001), p. 126.

- Short (1990), p. 117.

- Holst (1981), p. 40.

- Short (1990), p. 151.

- Mitchell (2001), pp. 139–140.

- Short (1990), pp. 126, 136.

- Gay, Simon; Mark Davies (5 April 2013). "A New Planets Suite". The Ringing World. 5319: 332. (subscription required)

- Holst (1981), p. 41.

- Short (1990), p. 135.

- Short (1990), p. 158; and Mitchell (2001), pp. 154–55

- Mitchell (2001), p. 156.

- Holst (1969), pp. 51–52.

- Short (1990), p. 144.

- "Savitri". The Times. 24 June 1921. p. 13.

- Short (1990), p. 159.

- "No. 30928". The London Gazette. 1 October 1918. p. 11615.

- Mitchell (2001), p. 161.

- Boult (1973), p. 35

- Boult (1979), p. 32.

- Mitchell (2001), p. 165

- Boult (1979), p. 34.

- Boult (1979), p. 33.

- Short (1990), p. 171

- Holst (1969), p. 77.

- Mitchell (2001), p. 212.

- "Music of the Week: Holst's 'Hymn of Jesus'". The Observer. 28 March 1920. p. 11.

- "Holst's 'Hymn of Jesus'". The Times. 26 March 1920. p. 12.

- Adams, Byron (Winter 1992). "Gustav Holst: The Man and His Music by Michael Short". The Musical Quarterly. 78 (4): 584. JSTOR 742478. (subscription required)

- "Mr. Holst on his New Opera". The Observer. 22 April 1923. p. 9.

- "The Perfect Fool". The Times. 15 May 1923. p. 12.

- Holst (1981), p. 59.

- Holst (1981), pp. 60–61.

- Holst (1981), p. 64

- Holst, I. (1974), pp. 150, 153, 171.

- Downes, Olin (13 February 1928). "Music: New York Symphony Orchestra". The New York Times. (subscription required)

- "Egdon Heath". The Times. 14 February 1928. p. 12.

- Adams, Byron (June 1989). "Egdon Heath, for Orchestra, Op. 47 by Gustav Holst;". Notes. 45 (4): 850. doi:10.2307/941241. JSTOR 941241. (subscription required)

- Mowat, Christopher (1998). Notes to Naxos CD 8.553696. Hong Kong: Naxos Records. OCLC 39462589.

- Holst (1981), p. 80.

- Holst, I. (1974), p. 189.

- Holst (1981), p. 78.

- Holst (1981), pp. 78–82.

- Holst (1981), p. 82.

- Hughes & Van Thal (1971), p. 86.

- "In Memory of Holst". The Times. 25 June 1934. p. 11.

- Short (1990), p. 346.

- Holst (1980), p. 664

- Kennedy, Michael. "Holst, Gustav". Oxford Companion to Music Online edition. Retrieved 14 April 2013. (subscription required)

- Quoted in Short (1990), p. 347

- Short (1990), pp. 336–38

- Gibbs (2000), p. 25.

- Holst (1980), p. 661

- Matthews, Colin (May 1984). "Some Unknown Holst". The Musical Times. 125 (1695): 269–272. doi:10.2307/961565. JSTOR 961565.

- Head, Raymond (September 1986). "Holst and India (I): 'Maya' to 'Sita'". Tempo (158): 2–7. JSTOR 944947. (subscription required)

- "Maybrick, Michael". Oxford Dictionary of Music Online edition. Retrieved 6 April 2013. (subscription required)

- Gustav Holst at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Short (1990), p. 61.

- Short (1990), p. 105.

- Holst (1986), p. 134.

- Dickinson (1995), pp. 7–9.

- Head, Raymond (March 1987). "Holst and India (II)". Journal (160): 27–36. JSTOR 944789. (subscription required)

- Head, Raymond (September 1988). "Holst and India (III)". Tempo (166): 35–40. JSTOR 945908. (subscription required)

- Dickinson (1995), p. 20

- Dickinson (1995), p. 192

- Dickinson (1995), pp. 110–111.

- Short (1990), p. 65.

- Dickinson (1995), pp. 192–193.

- Short (1990), p. 82.

- Dickinson (1995), p. 22.

- Holst (1980), p. 662

- Dickinson (1995), p. 167.

- Short (1990), p. 122.

- Dickinson (1995), p. 169.

- Dickinson (1995), p. 168.

- Short (1990), p. 123.

- Short (1990), pp. 126–127.

- Dickinson (1995), pp. 121–122.

- Dickinson (1995), pp. 123–124

- Short (1990), pp. 128–129.

- Short (1990), pp. 130–131.

- Holst (1980), p. 663

- Dickinson (1995), pp. 96–97.

- Short (1990), p. 137.

- Gibbs (2000), p. 128.

- Dickinson (1995), p. 25.

- Head, Raymond (July 1999). "The Hymn of Jesus: Holst's Gnostic Exploration of Time and Space". Tempo (209): 7–13. JSTOR 946668.

- Dickinson (1995), p. 36.

- Newman, Ernest (30 August 1923). "The Week in Music". The Manchester Guardian. p. 5.

- "The Unfamiliar Holst". The Times. 11 December 1956. p. 5.

- Short (1990), p. 214.

- Holst (1986), p. 72.

- Grace, Harvey (April 1925). "At the Boar's Head: Holst's New Work". The Musical Times. 66 (986): 305–310. JSTOR 912399.

- Greene, Richard (May 1992). "A Musico-Rhetorical Outline of Holst's 'Egdon Heath'". Music & Letters. 73 (2): 244–67. doi:10.1093/ml/73.2.244. JSTOR 735933. (subscription required)

- Short (1990), p. 263.

- Stephen Arthur Allen, "Symphony within: rehearing Holst's A Moorside Suite", The Musical Times (Winter, 2017), pp. 7–32

- Quoted in Short (1990), p. 351

- Short (1990), p. 420.

- Holst (1986), pp. 100–101.

- Short (1990), pp. 324–325.

- Dickinson (1995), p. 154.

- Short (1990), pp. 319–320.

- Dickinson (1995), p. 157.

- Short (1990), p. 205.

- "Columbia Records". The Times. 5 November 1925. p. 10.

- "Gramophone Notes". The Times. 9 June 1928. p. 12.

- Short (1990), p. 247.

- Sackville-West & Shawe-Taylor (1955), pp. 378–379.

- March (2007), pp. 617–623.

- "Savitri"; and "Wandering scholar / At the Boar's Head", WorldCat, accessed 24 March 2013

- From "GH: An account of Holst's attitude to the teaching of composition, by one of his pupils", first published in Crescendo, February 1949. Quoted by Short (1990), p. 339

- Tippett (1991), p. 15.

- Short (1990), p. 337.

- Short (1990), p. 339.

- "A New Memorial for Gustav Holst". Chichester Cathedral. Archived from the original on 22 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "In the Bleak Midwinter". BBC. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

Sources

- Boult, Adrian (1973). My Own Trumpet. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-02445-5.

- Boult, Adrian (1979). Music and Friends. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-10178-6.

- Dickinson, Alan Edgar Frederic (1995). Alan Gibbs (ed.). Holst's Music—A Guide. London: Thames. ISBN 0-905210-45-X.

- Dickinson, A E F (1957). "Gustav Holst". In Alfred Louis Bacharach (ed.). The Music Masters IV: The Twentieth Century. Harmondsworth: Penguin. OCLC 26234192.

- Gibbs, Alan (2000). Holst Among Friends. London: Thames Publishing. ISBN 978-0-905210-59-9.

- Holst, Gustav (1974). Letters to W. G. Whittaker. University of Glasgow Press. ISBN 0-85261-106-4.

- Holst, Imogen (1969). Gustav Holst (second ed.). London and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315417-X.

- Holst, Imogen (1974). A Thematic Catalogue of Gustav Holst's Music. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-10004-X.

- Holst, Imogen (1980). "Holst, Gustavus Theodore von". In Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 8. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Holst, Imogen (1981). The Great Composers: Holst (second ed.). London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-09967-X.

- Holst, Imogen (1986). The Music of Gustav Holst (third ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315458-7.

- Hughes, Gervase (1960). The Music of Arthur Sullivan. London: Macmillan. OCLC 16739230.

- Hughes, Gervase; Van Thal, Herbert (1971). The Music Lover's Companion. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode. ISBN 0-413-27920-0.

- Kennedy, Michael (1970). Elgar: Orchestral Music. London: BBC. OCLC 252020259.

- March, Ivan, ed. (2007). The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music, 2008. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-103336-3.

- Mitchell, Jon C (2001). A Comprehensive Biography of Composer Gustav Holst, with Correspondence and Diary Excerpts. Lewiston, N Y: E Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-7522-2.

- Moore, Jerrold Northrop (1992). Vaughan Williams—A Life in Photographs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816296-0.

- Rodmell, Paul (2002). Charles Villiers Stanford. Aldershot: Scolar Press. ISBN 1-85928-198-2.

- Rubbra, Edmund; Lloyd, Stephen, eds. (1974). Gustav Holst. London: Triad Press. ISBN 0-902070-12-6.

- Sackville-West, Edward; Shawe-Taylor, Desmond (1955). The Record Guide. London: Collins. OCLC 500373060.

- Short, Michael (1990). Gustav Holst: The Man and his Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-314154-X.

- Tippett, Michael (1991). Those Twentieth Century Blues. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6059-3.

- Vaughan Williams, Ralph (2008). Hugh Cobbe (ed.). Letters of Ralph Vaughan Williams. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925797-3.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gustav Holst. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gustav Holst |

- Gustav Holst at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- The Gustav Holst archive at the Britten-Pears Foundation

- Gustav Holst at IMDb

- Free scores by Gustav Holst in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores by Gustav Holst at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- The Gustav Holst Website (unofficial)

- Gustav Holst: The Lost Films (BBC production from the late 1970s, discovered 2009. Extracts)

- Turn back, O man (Op. 36a) – live recording by the Choir of Somerville College, Oxford (2012) on YouTube

- Works by or about Gustav Holst at Internet Archive

- Works by Gustav Holst at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)