Keith Jarrett

Keith Jarrett (born May 8, 1945) is an American jazz and classical music pianist and composer.[1]

Keith Jarrett | |

|---|---|

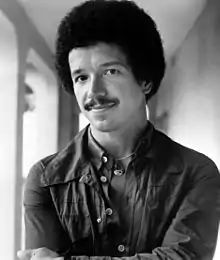

Jarrett in August 1975 | |

| Background information | |

| Born | May 8, 1945 Allentown, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz, classical, jazz fusion, free improvisation |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer |

| Instruments | Piano |

| Years active | 1966–2018 |

| Labels | Atlantic, ECM, Impulse!, Universal Classics |

| Associated acts | Art Blakey, Sam Brown, Gary Burton, Dennis Russell Davies, Miles Davis, Jack DeJohnette, Charlie Haden, Charles Lloyd, Airto Moreira, Paul Motian, Gary Peacock, Dewey Redman, Kenny Wheeler |

Jarrett started his career with Art Blakey, moving on to play with Charles Lloyd and Miles Davis. Since the early 1970s he has enjoyed a great deal of success as a group leader and a solo performer in jazz, jazz fusion, and classical music. His improvisations draw from the traditions of jazz and other genres, especially Western classical music, gospel, blues, and ethnic folk music.

In 2003 Jarrett received the Polar Music Prize, the first recipient of both the contemporary and classical musician prizes,[2] and in 2004 he received the Léonie Sonning Music Prize. His album The Köln Concert (1975) became the best-selling piano recording in history.

In 2008 he was inducted into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame in the magazine's 73rd Annual Readers' Poll.[3]

Jarrett has been unable to perform since suffering a stroke in February 2018, and a second stroke in May 2018, which left him partially paralyzed and unable to play with his left hand.[4]

Early years

Keith Jarrett was born on May 8, 1945, in Allentown, Pennsylvania, United States,[1] to a mother of Slovenian descent. Jarrett's grandmother was born in Segovci, near Apace in Slovenia, (at the time, this was in the Austria of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). Her own parents probably descended from the Slavic population of Prekmurje, a few miles away in a Hungarian part of the Empire almost totally populated by Slovenes. [5] Jarrett's father was of mostly German descent.[6] He grew up in suburban Allentown with significant early exposure to music.[7] Jarrett possesses absolute pitch, and he displayed prodigious musical talents as a young child. He began piano lessons before his third birthday, and at age five he appeared on a TV talent program hosted by the swing bandleader Paul Whiteman.[8] He gave his first formal piano recital at the age of seven, playing works by composers such as Mozart, Bach, Beethoven, and Saint-Saëns, and ending with two of his own compositions.[9] Encouraged by his mother, he took classical piano lessons with a series of teachers, including Eleanor Sokoloff of the Curtis Institute.

In his teens, as a student at Emmaus High School in Emmaus, Pennsylvania, Jarrett learned jazz and became proficient in it. He developed a strong interest in contemporary jazz; a Dave Brubeck performance was an early inspiration.[10] He had an offer to study classical composition in Paris with Nadia Boulanger, an opportunity that pleased his mother but that Jarrett, already leaning toward jazz, decided to turn down.[11]

After his graduation from Emmaus High School in 1963, Jarrett moved from Allentown to Boston where he attended the Berklee College of Music and played cocktail piano in local clubs. After a year he moved to New York City, where he played at the Village Vanguard.[12]

In New York, Art Blakey hired Jarrett to play with the Jazz Messengers. During a show he was noticed by Jack DeJohnette, who recognized the unknown pianist's talent and unstoppable flow of ideas. DeJohnette talked to Jarrett and recommended him to his band leader, Charles Lloyd. The Charles Lloyd Quartet had formed not long before and were exploring open, improvised forms while building supple grooves, and they were moving into terrain that was also being explored, although from another stylistic background, by some of the psychedelic rock bands of the west coast.[13] Their 1966 album Forest Flower was one of the most successful jazz recordings of the mid-1960s, and when they were invited to play The Fillmore in San Francisco, they won over the local hippie audience. The Quartet's tours across America, Europe, and Moscow made Jarrett a popular musician in rock and jazz. The tour also laid the foundation for a lasting musical bond with DeJohnette.

Jarrett began to record his own tracks as a leader of small groups, at first in a trio with Charlie Haden and Paul Motian. Life Between the Exit Signs (1967), his first album as a leader, was released by Vortex, followed by Restoration Ruin (1968), which Thom Jurek of AllMusic called "a curiosity in his catalog".[12] Not only does Jarrett barely touch the piano, but he plays all the other instruments on what is essentially a folk-rock album. Unusually, he also sings.[12] Somewhere Before, another trio album with Haden and Motian, followed in 1968 for Atlantic Records.

Miles Davis

The Charles Lloyd Quartet with Jarrett, Ron McClure and DeJohnette came to an end in 1968, after the recording of Soundtrack, because of disputes over money as well as artistic differences.[14] Jarrett was asked to join the Miles Davis group after the trumpeter heard him in a New York City club (according to another version Jarrett tells, Davis had brought his entire band to see a tour date of Jarrett's own trio in Paris; the Davis band being practically the only audience, the attention made Jarrett feel embarrassed). During his tenure with Davis, Jarrett played both Fender Contempo electronic organ and Fender Rhodes electric piano, alternating with Chick Corea; they can be heard side by side on some 1970 recordings: for example, on the August 1970 Isle of Wight Festival performance preserved in the film Miles Electric: A Different Kind of Blue and on Bitches Brew Live. After Corea left in 1970, Jarrett often played electric piano and organ simultaneously. Despite his growing dislike of amplified music and electric instruments within jazz, Jarrett continued with the group out of respect for Davis and because of his desire to work with DeJohnette. Jarrett has often cited Davis as a vital influence, both musical and personal, on his own thinking about music and improvisation.

Jarrett performs on several Davis albums: Miles Davis at Fillmore: Live at the Fillmore East, The Cellar Door Sessions (recorded December 16–19, 1970, at the Cellar Door club in Washington, DC). His keyboard playing features prominently on Live-Evil (which is largely composed of heavily edited Cellar Door recordings). Jarrett also plays electric organ on Get Up with It. Some other tracks from this period were released much later.[15]

1970s quartets

From 1971 to 1976, Jarrett added saxophonist Dewey Redman to the existing trio with Haden and Motian (who produced one more album as a trio, called The Mourning of A Star for Atlantic Records in 1971). The so-called "American quartet" was often supplemented by an extra percussionist, such as Danny Johnson, Guilherme Franco, or Airto Moreira, and occasionally by guitarist Sam Brown. The quartet members played various instruments, with Jarrett often being heard on soprano saxophone and percussion as well as piano; Redman on musette, a Chinese double-reed instrument; and Motian and Haden on a variety of percussion. Haden also produced a variety of unusual plucked and percussive sounds with his acoustic bass, even running it through a wah-wah pedal for one track ("Mortgage on My Soul", on the album Birth). The group recorded two albums for Atlantic Records in 1971, El Juicio (The Judgement) and Birth; another on Columbia Records called Expectations (that included guitar by Sam Brown, plus string and brass arrangements and for which Jarrett's contract with the label was terminated within a month of its release[16]); eight albums on Impulse! Records; and two on ECM.

Byablue and Bop-Be, albums recorded for Impulse!, mainly feature the compositions of Haden, Motian and Redman, as opposed to Jarrett's own, which dominated the previous albums. Jarrett's compositions and the strong musical identities of the group members gave this ensemble a very distinctive sound. The quartet's music is an amalgam of free jazz, straight-ahead post-bop, gospel music, and exotic, Middle-Eastern-sounding improvisations.

In the mid/late 1970s, concurrently with the American quartet, Jarrett led a "European quartet" which was recorded by ECM. This combo consisted of saxophonist Jan Garbarek, bassist Palle Danielsson, and drummer Jon Christensen. They played in a style similar to that of the American quartet, but with many of the avant-garde and Americana elements replaced by the European folk and classical music influences that characterized the work of ECM artists at the time.

Solo piano

Jarrett recorded a few solo pieces live under the guidance of Miles Davis at Washington's music club The Cellar Door in December 1970. These were done on electric pianos (Rhodes and Contempo), which Jarrett was loath to perform on.[17] Most parts of these recorded sets were released in 2007 on The Cellar Door Sessions featuring four improvisations by Jarrett.

Jarrett's first album for ECM, Facing You (1971), was a solo piano date recorded in the studio. He has continued to record solo piano albums in the studio intermittently throughout his career, including Staircase (1976), Invocations/The Moth and the Flame (1981), and The Melody at Night, with You (1999). Book of Ways (1986) is a studio recording of clavichord solos.

The studio albums are modestly successful entries in the Jarrett catalog, but in 1973, Jarrett also began playing totally improvised solo concerts, and it is the popularity of these voluminous concert recordings that made him one of the best-selling jazz artists in history. Albums released from these concerts were Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne (1973), to which Time magazine gave its 'Jazz Album of the Year' award; The Köln Concert (1975), which became the best-selling piano recording in history;[18] and Sun Bear Concerts (1976) – a 10-LP (and later 6-CD) box set.

Another of Jarrett's solo concerts, Dark Intervals (1987, Tokyo), had less of a free-form improvisation feel to it because of the brevity of the pieces. Sounding more like a set of short compositions, these pieces are nonetheless entirely improvised.

After a hiatus, Jarrett returned to the extended solo improvised concert format with Paris Concert (1990), Vienna Concert (1991), and La Scala (1995). These later concerts tend to be more influenced by classical music than the earlier ones, reflecting his interest in composers such as Bach and Shostakovich, and are mostly less indebted to popular genres such as blues and gospel. In the liner notes to Vienna Concert, Jarrett named the performance his greatest achievement and the fulfillment of everything he was aiming to accomplish: "I have courted the fire for a very long time, and many sparks have flown in the past, but the music on this recording speaks, finally, the language of the flame itself."[19]

Jarrett has commented that his best performances have been when he has had only the slightest notion of what he was going to play at the next moment. He also said that most people don't know "what he does", which relates to what Miles Davis said to him expressing bewilderment – as to how Jarrett could "play from nothing". In the liner notes of the Bremen Lausanne album Jarrett states something to the effect that he is a conduit for the 'Creator', something his mother had apparently discussed with him. This has caused occasional moments of confusion, where reportedly at a concert he was so indecisive as to what to play that he just sat at the piano in silence until someone in the audience yelled out "C-sharp major!", prompting Jarrett to thank the audience and begin playing.[20]

Jarrett's 100th solo performance in Japan was captured on video at Suntory Hall, Tokyo, in April 1987, and released the same year as Solo Tribute. This is a set of almost all standard songs. Another video recording, Last Solo, was released in 1987 from a solo concert at Kan-i Hoken hall in Tokyo in January 1984.

In the late 1990s, Jarrett was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome[12] and was unable to leave his home for long periods of time. It was during this period that he recorded The Melody at Night, with You, a solo piano effort consisting of jazz standards presented with very little of the reinterpretation he usually employs. The album had originally been a Christmas gift to his second wife, Rose Anne.[21]

By 2000, Jarrett had returned to touring, both solo and with the Standards Trio. Two 2002 solo concerts in Japan, Jarrett's first solo piano concerts following his illness, were released on the 2005 CD Radiance (a complete concert in Osaka, and excerpts from one in Tokyo), and the 2006 DVD Tokyo Solo (the entire Tokyo performance). In contrast with previous concerts (which were generally a pair of continuous improvisations 30–40 minutes long), the 2002 concerts consist of a linked series of shorter improvisations (some as short as a minute and a half, a few of 15 or 20 minutes).

In September 2005, at Carnegie Hall, Jarrett performed his first solo concert in North America in more than ten years, released a year later as a double-CD set, The Carnegie Hall Concert. In late 2008, he performed solo in the Salle Pleyel in Paris and at London's Royal Festival Hall, marking the first time Jarrett had played solo in London in 17 years. Recordings of these concerts were released in October 2009 on the album Paris / London: Testament.

The Standards Trio

In 1983, at the suggestion of ECM head Manfred Eicher,[22] Jarrett asked bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Jack DeJohnette, with whom he had worked on Peacock's 1977 album Tales of Another, to record an album of jazz standards, simply titled Standards, Volume 1. Two more albums, Standards, Volume 2 and Changes, both recorded at the same session, followed soon after. The success of these albums and the group's ensuing tour, which came as traditional acoustic post-bop was enjoying an upswing in the early 1980s, led to this new standards trio becoming one of the premier working groups in jazz, and certainly one of the most enduring, continuing to record and tour for more than 25 years. The Trio went on to record numerous live and studio albums consisting primarily of jazz repertory material.

The Jarrett-Peacock-DeJohnette trio also produced recordings that consist largely of challenging original material, including 1987's Changeless. Several of the standards albums contain an original track or two, some attributed to Jarrett, but most are improvisations on jazz standards. The live recordings Inside Out and Always Let Me Go (released in 2001 and 2002 respectively) marked a renewed interest by the trio in wholly improvised free jazz. By this point in their history, the musical communication among these three men had become nothing short of telepathic, and their group improvisations frequently take on a complexity that sounds almost composed. The standards trio undertook frequent world tours of recital halls (the only venues Jarrett, a notorious stickler for acoustics, will play) and was one of the few truly successful jazz groups to play both straight-ahead (as opposed to smooth) and free jazz.

A related recording, At the Deer Head Inn (1992), is a live album of standards recorded with Paul Motian replacing DeJohnette, at the venue in Delaware Water Gap, Pennsylvania, 40 miles from Jarrett's hometown, where he had his first job as a jazz pianist. It was the first time Jarrett and Motian had played together since the demise of the American quartet sixteen years earlier.

The Standard Trio disbanded in 2014 after more than 30 years.[23] The final concert of Keith Jarrett's trio was on November 30, 2014 at New Jersey Performing Arts Center, Newark, NJ, USA. The last encore was Thelonious Monk's composition "Straight, No Chaser". Peacock died in September 2020.

Classical music

Since the early 1970s, Jarrett's success as a jazz musician has enabled him to maintain a parallel career as a classical composer and pianist, recording almost exclusively for ECM Records.

In The Light, an album made in 1973, consists of short pieces for solo piano, strings, and various chamber ensembles, including a string quartet and a brass quintet, and a piece for cellos and trombones. This collection demonstrates a young composer's affinity for a variety of classical styles.

Luminessence (1974) and Arbour Zena (1975) both combine composed pieces for strings with improvising jazz musicians, including Jan Garbarek and Charlie Haden. The strings here have a moody, contemplative feel that is characteristic of the "ECM sound" of the 1970s, and is also particularly well suited to Garbarek's keening saxophone improvisations. From an academic standpoint, these compositions are dismissed by many classical music aficionados as lightweight, but Jarrett appeared to be working more towards a synthesis between composed and improvised music at this time, rather than the production of formal classical works. From this point on, however, his classical work would adhere to more conventional disciplines.

Ritual (1977) is a composed solo piano piece recorded by Dennis Russell Davies that is somewhat reminiscent of Jarrett's own solo piano recordings.

The Celestial Hawk (1980) is a piece for orchestra, percussion, and piano that Jarrett performed and recorded with the Syracuse Symphony under Christopher Keene. This piece is the largest and longest of Jarrett's efforts as a classical composer.

Bridge of Light (1993) is the last recording of classical compositions to appear under Jarrett's name. The album contains three pieces written for a soloist with orchestra, and one for violin and piano. The pieces date from 1984 and 1990.

In 1988, New World Records released the CD Lou Harrison: Piano Concerto and Suite for Violin, Piano and Small Orchestra, featuring Jarrett on piano, with Naoto Otomo conducting the piano concerto with the New Japan Philharmonic. Robert Hughes conducted the Suite for Violin, Piano, and Small Orchestra. In 1992 came the release of Jarrett's performance of Peggy Glanville-Hicks's Etruscan Concerto, with Dennis Russell Davies conducting the Brooklyn Philharmonic. This was released on Music Masters Classics, with pieces by Lou Harrison and Terry Riley. In 1995 Music Masters Jazz released a CD on which one track featured Jarrett performing the solo piano part in Lousadzak, a 17-minute piano concerto by American composer Alan Hovhaness. The conductor again was Davies. Most of Jarrett's classical recordings are of older repertoire, but he may have been introduced to this modern work by his one-time manager George Avakian, who was a friend of the composer. Jarrett has also recorded classical works for ECM by composers such as Bach, Handel, Shostakovich, and Arvo Pärt.

In 2004, Jarrett was awarded the Léonie Sonning Music Prize.[24] The award, usually associated with classical musicians and composers, had previously been given to only one other jazz musician: Miles Davis.

Other works

Jarrett has also played harpsichord, clavichord, organ, soprano saxophone, and drums. He often played saxophone and various forms of percussion in the American quartet, though his recordings since the breakup of that group have rarely featured these instruments. On the majority of his recordings in the last 20 years, he has played acoustic piano only. He has spoken with some regret of his decision to give up playing the saxophone, in particular.

On April 15, 1978, Jarrett was the musical guest on Saturday Night Live. His music has also been used on many television shows, including The Sopranos on HBO. The 2001 German film Bella Martha (English title: Mostly Martha), whose music consultant was ECM founder and head Manfred Eicher, features Jarrett's "Country", from the European quartet album My Song and "U Dance" from the album Tribute.

Idiosyncrasies

One of Jarrett's trademarks is his frequent, loud vocalizations, similar to those of Glenn Gould, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, Erroll Garner, Oscar Peterson, Ralph Sutton, Willie "The Lion" Smith, Paul Asaro, and Cecil Taylor. Jarrett is also physically active while playing jazz and improvised solo performances, but are generally absent whenever he plays classical repertory. Jarrett has noted his vocalizations are based on involvement, not content, and are more of an interaction than a reaction.[25][26]

Jarrett is highly intolerant of audience noise, especially during solo improvised performances. He feels extraneous noise affects his inspiration and distracts from the purity of the sound. Cough drops are routinely supplied to Jarrett's audiences in cold weather, and he has been known to stop playing and lead the crowd in a group cough.[27] He has also complained onstage about audience members taking photographs,[28] and has performed in the dark to prevent this.[29]

Jarrett is known to be opposed to electronic instruments and equipment. His liner notes for the 1973 album Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne states: "I am, and have been, carrying on an anti-electric-music crusade of which this is an exhibit for the prosecution. Electricity goes through all of us and is not to be relegated to wires."[30] He has largely eschewed electric or electronic instruments since his time with Miles Davis. However, in October 1972 he did play electric piano in addition to piano on Freddie Hubbard's Sky Dive.

Personal life

Jarrett lives in an 18th-century farmhouse in Oxford Township, New Jersey, in rural Warren County where he uses an adjacent barn as a recording and practice studio.[31]

Jarrett was a follower of the teachings of George Gurdjieff (1866–1949) for many years,[32] and in 1980 recorded an album of Gurdjieff's compositions, called Sacred Hymns, for ECM. Jarrett has also visited Princeton University's ESP lab run by Robert Jahn.[33][34] He is a Christian Scientist.[4]

In 1964, Jarrett married Margot Erney, a high school girlfriend from Emmaus with whom Jarrett had reconnected in Boston. The couple had two sons, Gabriel and Noah, but divorced in 1979.[35] He and his second wife Rose Anne (née Colavito) divorced in 2010 after a 30-year marriage. Jarrett has four younger brothers, two of whom are involved in music. Chris Jarrett is also a pianist, and Scott Jarrett is a producer and songwriter. Of the two sons from his first marriage, Noah Jarrett is a bassist and composer while Gabriel is a drummer based in Vermont.

In the late 1970s, James Lincoln Collier observed "Many of his fans think he is black, and indeed Jarrett encourages this impression. His skin is dark; he wears a small mustache and affects an Afro. He is, in fact, of Scots‐Irish and Hungarian descent."[36] He relates an incident when black jazz musician Ornette Coleman approached him backstage, and said something like, "Man, you've got to be black. You just have to be black," to which Jarrett replied, "I know. I know. I'm working on it."[21]

In a September 11, 2000 interview with Terri Gross, Jarrett revealed that Chronic Fatigue Syndrome had required him to radically overhaul his piano to have less "breakaway" keypress resistance in order for him to keep playing.[21]

Interviewed by NPR's Rachel Martin for his 70th birthday in 2015, Jarrett explained the notable involuntary vocalisations made during his performances: "It's potential limitlessness that I'm feeling at that moment. If you think about it, it's often in a space between phrases, [when I'm thinking,] "How did I get to this point where I feel so full?" And if you felt full of some sort of emotion you would have to make a sound. So that's actually what it is — with the trio, without the trio, solo. Luckily for me, I don't do it with classical music.[37]

On June 25, 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Keith Jarrett among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal Studios fire.[38]

Jarrett suffered two major strokes in February and May 2018. After the second he was paralyzed and spent nearly two years in a rehabilitation facility. Although he regained a limited ability to walk with a cane and can play piano with his right hand, he remains partly paralyzed on his left side and is not expected to perform again. “I don’t know what my future is supposed to be" Jarrett told The New York Times in October 2020. "I don’t feel right now like I’m a pianist."[39]

Lawsuit against Steely Dan

Following the release of the album Gaucho in 1980 by the U.S. rock band Steely Dan, Jarrett sued the band for copyright infringement. Gaucho's title track, credited to Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, bore a resemblance to Jarrett's "Long As You Know You're Living Yours" from Jarrett's 1974 album Belonging. In an interview with Musician magazine, Becker and Fagen were asked about the similarity between the two pieces of music, and Becker told Musician that he loved the Jarrett composition, while Fagen said they had been influenced by it. After their comments were published, Jarrett sued, and Becker and Fagen were legally obligated to add his name to the credits and provide Jarrett with publishing royalties.[40]

Discography

References

- Colin Larkin, ed. (1997). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music (Concise ed.). Virgin Books. p. 666/7. ISBN 1-85227-745-9.

- "POLAR MUSIC PRIZE". December 12, 2003. Archived from the original on December 12, 2003. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- "BMI Jazz Composers Top 'Downbeat' Readers Poll". bmi.com. Retrieved November 14, 2008.

- Chinen, Nate (October 21, 2020). "Keith Jarrett Confronts a Future Without the Piano". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- "Keith Jarrett: 75 let slavnega glasbenika prekmurskih korenin" [Keith Jarrett: 75 years of a famous musician with Prekmurje roots] (in Slovenian). vestnik.si.

Although the lexicons write about him as an American musician, it should be remembered that his grandmother Anna Temlin, with whom he grew up, was from Prekmurje

- Carr, Ian. Keith Jarrett, p. 1.

- "Music: Growing Into The Silence". Time. October 23, 1995.

- Carr, Ian. Keith Jarrett: The Man and His Music (New York: Da Capo, 1992), p. 8.

- Carr, Ian. Keith Jarrett, p. 7.

- Iverson, Ethan (September 2009). "Interview with Keith Jarrett". EthanIverson.com. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Carr, Ian. Keith Jarrett, p. 17.

- Jurek, Thom. Allmusic "Keith Jarrett" biography. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- Carr, Ian, Keith Jarrett, p. 32.

- Carr, Ian. Keith Jarrett, pp. 38–39.

- Davis, Miles. The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions. Columbia/Legacy, 2003.

- Cook, Richard; Morton, Brian (2008). The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings. Penguin. p. 768. ISBN 978-0-141-03401-0.

- "MILES BEYOND | The Cellar Door". Miles-beyond.com. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- Keith Jarrett Biography Archived March 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, All About Jazz. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- Keith Jarrett, liner notes, Vienna Concert, ECM Records, 1992.

- "When Keith Jarrett Sits Down at the Piano, Not Even He Knows What He's Going to Play". PEOPLE.com.

- "Jazz Great Keith Jarrett Discusses Living with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS)". Prohealth.com. September 14, 2000. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- Smith, Steve. "40 Years Old, a Musical House Without Walls". New York Times, December 23, 2009.

- "Keith Jarrett's jazz trio releases its first album since disbanding". The Economist. March 16, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- "[UDV] Léonie Sonnings Musikfond". Int.sonning.clients.pinebits.dk. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- Jarrett, Keith. The Art of Improvisation. (DVD). Euroarts, 2005

- Garratt, John (May 27, 2013). "Keith Jarrett / Gary Peacock / Jack DeJohnette: Somewhere". PopMatters. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- Minim (January 24, 2011). "Why you should be as unprofessional as Keith Jarrett". PlayJazz. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- JHarv (August 9, 2007). "Jazz Legend Hates Cell Phone Cameras More Than We Do". Idolator. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- Conrad, Thomas (July 13, 2013). "Keith Jarrett's Dark Night in Perugia". Jazz Times. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne (liner notes). Keith Jarrett. ECM Records. 1973. ECM 1035-1037.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Corinna Da Fonseca-Wollheim (January 9, 2009). "A One-of-a-Kind Artist Prepares for His Solo". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- Chase, Christopher W. (October 1, 2010). "Music, Aesthetics and Legitimation: Keith Jarrett and the 'Fourth Way'". Academia.edu. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- Samuel, Lawrence R. (2011). Supernatural America: A Cultural History. ABC-CLIO. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-313-39899-5. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- Carey, Benedict (February 10, 2007). "A Princeton Lab on ESP Plans to Close Its Doors". The New York Times. p. 2. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- Tim Blangger (September 14, 2008). "Keith Jarrett". Articles.mcall.com. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- Collier, James Lincoln (January 7, 1979). "Jazz in the Jarrett Mode". Nytimes.com.

- "At 70, Keith Jarrett Is Learning How To Bottle Inspiration". NPR.org.

- Rosen, Jody (June 25, 2019). "Here Are Hundreds More Artists Whose Tapes Were Destroyed in the UMG Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- Chinen, Nate (October 21, 2020). "Keith Jarrett Confronts a Future Without the Piano". Nytimes.com. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- Don't Mess with Steely Dan; Brian Sweet, Steely Dan: Reelin' in the Years (London: Omnibus Press, 1994), p. 144.

Sources

- Carr, Ian. Keith Jarrett: The Man and His Music. 1992 ISBN 0-586-09219-6

- Carr, Ian; Fairweather, Digby; Priestley, Brian. The Rough Guide to Jazz. 2003 ISBN 1-84353-256-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Keith Jarrett. |

- Keith Jarrett discography at Discogs

- Art of the States: Keith Jarrett performing Lousadzak, op. 48 (1944) by Alan Hovhaness

- Keith Jarrett on ECM Records.

- "Keith Jarrett Standards Trio Celebrates Its 25th Anniversary" by Ted Gioia Jazz.com

- Keith Jarrett on Marian McPartland's Piano Jazz (NPR)

- "Zen in the Art of Jazz"

- 1997 New York Times profile of Jarrett