Center of origin

A centre of origin (or centre of diversity) is a geographical area where a group of organisms, either domesticated or wild, first developed its distinctive properties.[2] They are also considered centers of diversity. Centers of origin were first identified in 1924 by Nikolai Vavilov.

Plants

Locating the origin of crop plants is basic to plant breeding. This allows one to locate wild relatives, related species, and new genes (especially dominant genes, which may provide resistance to diseases). Knowledge of the origins of crop plants is important in order to avoid genetic erosion, the loss of germplasm due to the loss of ecotypes and landraces, loss of habitat (such as rainforests), and increased urbanization. Germplasm preservation is accomplished through gene banks (largely seed collections but now frozen stem sections) and preservation of natural habitats (especially in centers of origin).

Vavilov centers

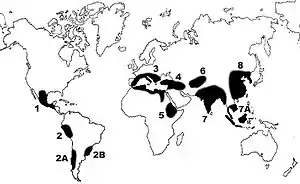

A Vavilov Centre (of Diversity) is a region of the world first indicated by Nikolai Vavilov to be an original centre for the domestication of plants.[4] For crop plants, Nikolai Vavilov identified differing numbers of centers: three in 1924, five in 1926, six in 1929, seven in 1931, eight in 1935 and reduced to seven again in 1940.[5][6]

Vavilov argued that plants were not domesticated somewhere in the world at random, but that there were regions where domestication started. The centre of origin is also considered the center of diversity.

Vavilov centres are regions where a high diversity of crop wild relatives can be found, representing the natural relatives of domesticated crop plants. Later in 1935 Vavilov divided the centers into 12, giving the following list:

- Chinese centre

- Indian centre

- Indo-Malayan centre

- Central Asiatic centre

- Persian centre

- Mediterranean centre

- Abyssinian centre

- South American centre

- Central American centre

- Chilean centre

- Brazilian-Paraguayan centre

- North American centre

Cultivated plants of eight world centres of origin [7][8]

| Centre | Plants |

|---|---|

| 1) South Mexican and Central American Centre | Includes southern sections of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and Costa Rica.

|

| 2) South American Centre | 62 plants listed; three subcentres

2) Peruvian, Ecuadorean, Bolivian Center:

2A) Chiloe Centre (Island near the coast of southern Chile)

2B) Brazilian-Paraguayan Center |

| 3) Mediterranean Centre | Includes the borders of the Mediterranean Sea. 84 listed plants

|

| 4) Middle East | Includes interior of Asia Minor, all of Transcaucasia, Iran, and the highlands of Turkmenistan. 83 species

|

| 5) Abyssinian Centre | Includes Ethiopia, Eritrea, and part of Somalia. 38 species listed; rich in wheat and barley.

|

| 6) Central Asiatic Centre | Includes Northwest India (Punjab, Northwest Frontier Provinces and Kashmir), Afghanistan, Tadjikistan, Uzbekistan, and western Tian-Shan. 43 plants |

| 7) Indian Centre | Two subcentres

7) Indo-Burma: Main Centre (India): Includes Assam, Bangladesh and Burma, but not Northwest India, Punjab, nor Northwest Frontier Provinces, 117 plants

7A) Siam-Malaya-Java: statt Indo-Malayan Centre: Includes Indo-China and the Malay Archipelago, 55 plants

|

| 8) Chinese Centre | A total of 136 endemic plants are listed in the largest independent center

|

Importance

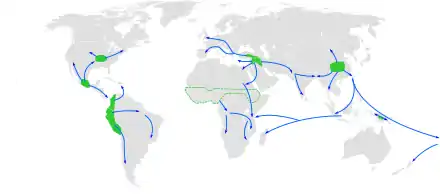

In 2016, researchers linked the origins and primary regions of diversity ("areas typically including the locations of the initial domestication of crops, encompassing the primary geographical zones of crop variation generated since that time, and containing relatively high species richness in crop wild relatives") of food and agricultural crops with their current importance around the world in modern national food supplies and agricultural production. The results indicated that foreign crops were 68.7% of national food supplies as a global mean, and their usage has greatly increased in the last fifty years.[10]

References

- Ladizinsky, G. (1998). Plant Evolution under Domestication. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers

- "International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2009: Article 2. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Diamond, J.; Bellwood, P. (2003). "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions". Science. 300 (5619): 597–603. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1013.4523. doi:10.1126/science.1078208. PMID 12714734. S2CID 13350469.

- Blaine P. Friedlander Jr (2000-06-20). "Cornell and Polish research scientists lead effort to save invaluable potato genetic archive in Russia". Retrieved 2008-03-19.

- Vavilov, N. I.; Löve, Doris (trans.) (1992). Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants. Cambridge University Press. p. xxi. ISBN 978-0521404273.

- Corinto, Gian Luigi (2014). "Nikolai Vavilov's Centers of Origin of Cultivated Plants With a View to Conserving Agricultural Biodiversity". Human Evolution. 29 (4): 285–301.

- Adapted from Vavilov (1951) by R. W. Schery, Plants for Man, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1972

- History of Horticulture, Jules Janick, Purdue University, 2002

- Gross, B. L.; Zhao, Z. (21 April 2014). "Archaeological and genetic insights into the origins of domesticated rice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (17): 6190–6197. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.6190G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1308942110. PMC 4035933. PMID 24753573.

- Khoury, C.K.; Achicanoy, H.A.; Bjorkman, A.D.; Navarro-Racines, C.; Guarino, L.; Flores-Palacios, X.; Engels, J.M.M.; Wiersema, J.H.; Dempewolf, H.; Sotelo, S.; Ramírez-Villegas, J.; Castañeda-Álvarez, N.P.; Fowler, C.; Jarvis, A.; Rieseberg, L.H.; Struik, P.C. (2016). "Origins of food crops connect countries worldwide". Proc. R. Soc. B. 283 (1832): 20160792. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.0792. PMC 4920324.