Circular economy

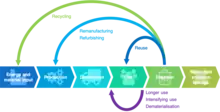

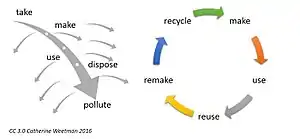

A circular economy (also referred to as "circularity"[2]) is an economic system aimed at eliminating waste and the continual use of resources. Circular systems employ reuse, sharing, repair, refurbishment, remanufacturing and recycling to create a closed-loop system, minimising the use of resource inputs and the creation of waste, pollution and carbon emissions.[3] The circular economy aims to keep products, equipment and infrastructure[4] in use for longer, thus improving the productivity of these resources. Waste materials and energy should become input for other processes: either a component or recovered resource for another industrial process or as regenerative resources for nature (e.g., compost). This regenerative approach is in contrast to the traditional linear economy, which has a "take, make, dispose" model of production.[5]

Sustainability

Intuitively, the circular economy would appear to be more sustainable than the current linear economic system. Reducing the resources used, and the waste and leakage created, conserves resources and helps to reduce environmental pollution. However, it is argued by some that these assumptions are simplistic; that they disregard the complexity of existing systems and their potential trade-offs. For example, the social dimension of sustainability seems to be only marginally addressed in many publications on the circular economy. There are cases that might require different or additional strategies, like purchasing new, more energy-efficient equipment. By reviewing the literature, a team of researchers from Cambridge and TU Delft could show that there are at least eight different relationship types between sustainability and the circular economy.[3] In addition, it is important to underline the innovation aspect in the heart of sustained development based on circular economy components.[6]

Scope

The circular economy can cover a broad scope. Researchers have focused on different areas such as industrial applications with both product-oriented, natural resources and services,[7] practice and policies[8] to better understand the limitations that the CE currently faces, strategic management for details of the circular economy and different outcomes such as potential re-use applications[9] and waste management.[10]

The circular economy includes products, infrastructure, equipment and services, and applies to every industry sector. It includes 'technical' resources (metals, minerals, fossil resources) and 'biological' resources (food, fibres, timber, etc.).[5] Most schools of thought advocate a shift from fossil fuels to the use of renewable energy, and emphasize the role of diversity as a characteristic of resilient and sustainable systems. The circular economy includes discussion of the role of money and finance as part of the wider debate, and some of its pioneers have called for a revamp of economic performance measurement tools.. One study points out how modularisation could become a cornerstone to enable circular economy and enhance the sustainability of energy infrastructure.[11] One example of a circular economy model is the implementation of renting models in traditional ownership areas (e.g. electronics, clothes, furniture, transportation). Through renting the same product to several clients, manufacturers can increase revenues per unit, thus decreasing the need to produce more to increase revenues. Recycling initiatives are often described as a circular economy and are likely to be the most widespread models.

Background

As early as 1966 Kenneth Boulding raised awareness of an "open economy" with unlimited input resources and output sinks, in contrast with a "closed economy", in which resources and sinks are tied and remain as long as possible a part of the economy. Boulding's essay "The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth"[12] is often cited as the first expression of the "circular economy",[13] although Boulding does not use that phrase.

The circular economy is grounded in the study of feedback-rich (non-linear) systems, particularly living systems.[5] The contemporary understanding of the Circular Economy and its practical applications to economic systems evolved incorporating different features and contributions from a variety of concepts sharing the idea of closed loops. Some of the relevant theoretical influences are cradle to cradle, laws of ecology (e.g., Barry Commoner § The Closing Circle), looped and performance economy (Walter R. Stahel), regenerative design, industrial ecology, biomimicry and blue economy (see section "Related concepts").[3]

The circular economy was further modelled by British environmental economists David W. Pearce and R. Kerry Turner in 1989. In Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment,[14] they pointed out that a traditional open-ended economy was developed with no built-in tendency to recycle, which was reflected by treating the environment as a waste reservoir.[15]

In the early 1990s, Tim Jackson began to create the scientific basis for this new approach to industrial production in his edited collection Clean Production Strategies,[16] including chapters from pre-eminent writers in the field, such as Walter R Stahel, Bill Rees and Robert Constanza. At the time still called 'preventive environmental management', his follow-on book Material Concerns: Pollution, Profit and Quality of Life[17] synthesised these findings into a manifesto for change, moving industrial production away from an extractive linear system towards a more circular economy.

Emergence of the idea

In their 1976 research report to the European Commission, "The Potential for Substituting Manpower for Energy", Walter Stahel and Genevieve Reday sketched the vision of an economy in loops (or circular economy) and its impact on job creation, economic competitiveness, resource savings and waste prevention. The report was published in 1982 as the book Jobs for Tomorrow: The Potential for Substituting Manpower for Energy.[18]

In 1982, Walter Stahel was awarded third prize in the Mitchell Prize competition on sustainable business models with a paper The Product-Life Factor. First prize went to the then US Secretary of Agriculture, second prize to Amory and Hunter Lovins, fourth prize to Peter Senge.

Considered as one of the first pragmatic and credible sustainability think tanks, the main goals of Stahel's institute are to extend the working life of products, to make goods last longer, to re-use existing goods and ultimately to prevent waste. This model emphasizes the importance of selling services rather than products, an idea referred to as the "functional service economy" and sometimes put under the wider notion of "performance economy". This model also advocates "more localization of economic activity".[19]

Promoting a circular economy was identified as national policy in China's 11th five-year plan starting in 2006.[20] The Ellen MacArthur Foundation has more recently outlined the economic opportunity of a circular economy, bringing together complementary schools of thought in an attempt to create a coherent framework, thus giving the concept a wide exposure and appeal.[21]

Most frequently described as a framework for thinking, its supporters claim it is a coherent model that has value as part of a response to the end of the era of cheap oil and materials, moreover contributing to the transition for a low carbon economy. In line with this, a circular economy can contribute to meeting the COP 21 Paris Agreement. The emissions reduction commitments made by 195 countries at the COP 21 Paris Agreement, are not sufficient to limit global warming to 1.5 °C. To reach the 1.5 °C ambition it is estimated that additional emissions reductions of 15 billion tonnes CO2 per year need to be achieved by 2030. Circle Economy and Ecofys estimated that circular economy strategies may deliver emissions reductions that could basically bridge the gap by half.[22]

Moving away from the linear model

Linear "take, make, dispose" industrial processes, and the lifestyles dependent on them, use up finite reserves to create products with a finite lifespan, which end up in landfills or in incinerators. The circular approach, by contrast, takes insights from living systems. It considers that our systems should work like organisms, processing nutrients that can be fed back into the cycle — whether biological or technical — hence the "closed loop" or "regenerative" terms usually associated with it. The generic circular economy label can be applied to or claimed by several different schools of thought, but all of them gravitate around the same basic principles.

One prominent thinker on the topic is Walter R. Stahel, an architect, economist, and a founding father of industrial sustainability. Credited with having coined the expression "Cradle to Cradle" (in contrast with "Cradle to Grave", illustrating our "Resource to Waste" way of functioning), in the late 1970s, Stahel worked on developing a "closed loop" approach to production processes, co-founding the Product-Life Institute in Geneva. In the UK, Steve D. Parker researched waste as a resource in the UK agricultural sector in 1982, developing novel closed-loop production systems. These systems mimicked and worked with the biological ecosystems they exploited.

Towards the circular economy

In 2013, a report was released entitled Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. The report, commissioned by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and developed by McKinsey & Company, was the first of its kind to consider the economic and business opportunity for the transition to a restorative, circular model. Using product case studies and economy-wide analysis, the report details the potential for significant benefits across the EU. It argues that a subset of the EU manufacturing sector could realize net materials cost savings worth up to $630 billion annually towards 2025—stimulating economic activity in the areas of product development, remanufacturing and refurbishment. Towards the Circular Economy also identified the key building blocks in making the transition to a circular economy, namely in skills in circular design and production, new business models, skills in building cascades and reverse cycles, and cross-cycle/cross-sector collaboration.[23]

Another report by WRAP and the Green Alliance (called "Employment and the circular economy: job creation in a more resource efficient Britain"), done in 2015 has examined different public policy scenarios to 2030. It estimates that, with no policy change, 200,000 new jobs will be created, reducing unemployment by 54,000. A more aggressive policy scenario could create 500,000 new jobs and permanently reduce unemployment by 102,000.[24]

On the other hand, implementing a circular economy in the United States has been presented by Ranta et al.[7] who analyzed the institutional drivers and barriers for the circular economy in different regions worldwide, by following the framework developed by Scott R.[25] In the article, different worldwide environment-friendly institutions were selected, and two types of manufacturing processes were chosen for the analysis (1) a product-oriented, and (2) a waste management.[7][25] Specifically, in the U.S., the product-oriented company case in the study was Dell, a US manufacturing company for computer technology, which was the first company to offer free recycling to customers and to launch to the market a computer made from recycling materials from a verified third-party source.[7] Moreover, the waste management case that includes many stages such as collection, disposal, recycling[26] in study was Republic Services, the second-largest waste management company in the US. The approach to measuring the drivers and barriers was to first identify indicators for their cases in study and then to categorize these indicators into drivers when the indicator was in favor of the circular economy model or a barrier when it was not.[7]

Circular business models

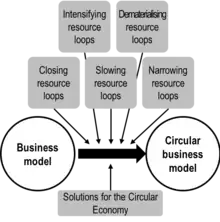

While the initial focus of academic, industry, and policy activities was mainly focused on the development of re-X (recycling, remanufacturing, reuse, etc.) technology, it soon became clear that the technological capabilities increasingly exceed their implementation. To leverage this technology for the transition towards a circular economy, various stakeholders have to work together. This shifted attention towards business-model innovation as a key leverage for 'circular' technology adaption.[28] Rheaply, a platform that aims to scale reuse within and between organizations, is an example of a technology that focuses on asset management & disposition to support organizations transitioning to circular business models.[29]

Circular business models can be defined as business models that are closing, narrowing, slowing, intensifying and dematerializing loops, to minimize the resource inputs into and the waste and emission leakage out of the organizational system. This comprises recycling measures (closing), efficiency improvements (narrowing), use phase extensions (slowing), a more intense use phase (intensifying), and the substitution of products by service and software solutions (dematerializing).[27] These strategies can be achieved through the purposeful design of material recovery processes and related circular supply chains.[30] As illustrated in the Figure, these five approaches to resource loops can also be seen as generic strategies or archetypes of circular business model innovation.

Circular business models, as the economic model more broadly, can have different emphases and various objectives, for example: extend the life of materials and products, where possible over multiple 'use cycles'; use a 'waste = food' approach to help recover materials, and ensure those biological materials returned to earth are benign, not toxic; retain the embedded energy, water and other process inputs in the product and the material for as long as possible; Use systems-thinking approaches in designing solutions; regenerate or at least conserve nature and living systems; push for policies, taxes and market mechanisms that encourage product stewardship, for example 'polluter pays' regulations.[31]

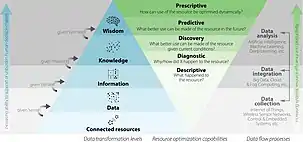

Digital circular economy

Building on circular business model innovation, digitalization and digital technologies (e.g., Internet of Things, Big Data, Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain) are seen as a key enabler for upscaling the circular economy.[33][34] Also referred to as the data economy, the central role of digital technologies for accelerating the circular economy transition is emphasized within the Circular Economy Action Plan of the European Green deal. The smart circular economy framework illustrates this by establishing a link between digital technologies and sustainable resource management.[32] This allows assessment of different digital circular economy strategies with their associated level of maturity, providing guidance on how to leverage data and analytics to maximize circularity (i.e., optimizing functionality and resource intensity). Supporting this, a Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda for circular economy has been recently published in the framework of the Horizon 2020 project CICERONE that puts digital technologies at the core of many key innovation fields (waste management, industrial symbiosis, products traceability).[35]

Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE)[36]

In 2018, the World Economic Forum, World Resources Institute, Philips, Ellen MacArthur Foundation, United Nations Environment Programme, and over 40 other partners launched the Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE).[37] PACE follows on the legacy of WEF's CEO-led initiative, Project MainStream, which sought to scale up circular economy innovations.[38] PACE's original intent has three focal areas: (1) developing models of blended finance for circular economy projects, especially in developing and emerging economies; (2) creating policy frameworks to address specific barriers to advancing the circular economy; and (3) promoting public–private partnership for these purposes.[39][40]

In 2020, PACE released a report with partner Circle Economy claiming that the world is 8.6% circular, claiming all countries are "developing countries" given the unsustainable levels of consumption in countries with higher levels of human development.[41][42]

PACE is a coalition of CEOs and Ministers--including the leaders of global corporations like IKEA, Coca-Cola, Alphabet Inc., and DSM (company), governmental partners and development institutions from Denmark, The Netherlands, Finland, Rwanda, UAE, China, and beyond.[43][44] Initiatives currently managed under PACE include the Capital Equipment Coalition with Philips and numerous other partners[45][46][47] and the Global Battery Alliance with over 70 partners.[48][49] In January 2019, PACE released a report entitled "A New Circular Vision for Electronics: Time for a Global Reboot" (in support of the United Nations E-waste Coalition.[50][51]

The coalition is hosted by a Secretariat headed by David B. McGinty, former leader of the Human Development Innovation Fund and Palladium International, and Board Member of BoardSource.[52][53] Board Members include Inger Andersen, Frans van Houten, Ellen MacArthur, Lisa P. Jackson, and Stientje van Veldhoven.[54]

Circular economy standard BS 8001:2017

To provide authoritative guidance to organizations implementing circular economy (CE) strategies, in 2017, the British Standards Institution (BSI) developed and launched the first circular economy standard "BS 8001:2017 Framework for implementing the principles of the circular economy in organizations".[55] The circular economy standard BS 8001:2017 tries to align the far-reaching ambitions of the CE with established business routines at the organizational level. It contains a comprehensive list of CE terms and definitions, describes the core CE principles, and presents a flexible management framework for implementing CE strategies in organizations. Little concrete guidance on circular economy monitoring and assessment is given, however, as there is no consensus yet on a set of central circular economy performance indicators applicable to organizations and individual products.[56]

Development of ISO/TC 323 circular economy standard

In 2018, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) established a technical committee, TC 323, in the field of circular economy to develop frameworks, guidance, supporting tools, and requirements for the implementation of activities of all involved organizations, to maximize the contribution to Sustainable Development.[57] Four new ISO standards are under development and in the direct responsibility of the committee (consisting of 70 participating members and 11 observing members).

Critiques of circular economy models

There is some criticism of the idea of the circular economy. As Corvellec (2015) put it, the circular economy privileges continued economic growth with soft "anti-programs", and the circular economy is far from the most radical "anti-program".[58] Corvellec (2019) raised the issue of multi-species and stresses "impossibility for waste producers to dissociate themselves from their waste and emphasizes the contingent, multiple, and transient value of waste".[59]:217 "Scatolic engagement draws on Reno's analogy of waste as scats and of scats as signs for enabling interspecies communication. This analogy stresses the impossibility for waste producers to dissociate themselves from their waste and emphasizes the contingent, multiple, and transient value of waste".[59]:217

A key tenet of a scatolic approach to waste is to consider waste as unavoidable and worthy of interest. Whereas total quality sees in waste a sign of failure, a scatolic understanding sees a sign of life. Likewise, whereas the Circular Economy analogy of a circle evokes endless perfection, the analogy of scats evokes disorienting messiness. A scatolic approach features waste as a lively matter open for interpretation, within organizations as well as across organizational species.[59]:219

Corvellec and Stål (2019) are mildly critical of apparel manufacturing circular economy take-back systems as ways to anticipate and head off more severe waste reduction programs:

Apparel retailers exploit that the circular economy is evocative but still sufficiently vague to create any concrete policies (Lüdeke‐Freund, Gold, & Bocken, 2019) that might hinder their freedom of action (Corvellec & Stål, 2017). Their business-centered qualification of take-back systems amounts to an engagement in "market action (...) as leverage to push policymakers to create or repeal particular rules," as Funk and Hirschman (2017:33) put it.[60]:26

Research by Zink and Geyer (2017: 593) questioned the circular economy's engineering-centric assumptions: "However, proponents of the circular economy have tended to look at the world purely as an engineering system and have overlooked the economic part of the circular economy. Recent research has started to question the core of the circular economy—namely, whether closing material and product loops do, in fact, prevent primary production."[61]

There are other critiques of the circular economy (CE).[62][63] For example, Allwood (2014) discussed the limits of CE 'material circularity', and questioned the desirability of the CE in a reality with growing demand.[64] Do CE secondary production activities (reuse, repair, & remake) actually reduce, or instead displace, primary production (natural resource extraction)? The problem CE overlooks, its untold story, is how displacement is governed mainly by market forces, according to McMillan et al. (2012).[65] It's the tired old narrative, that the invisible hand of market forces will conspire to create full displacement of virgin material of the same kind, said Zink & Geyer (2017).[61] Korhonen, Nuur, Feldmann, and Birkie (2018) argued that "the basic assumptions concerning the values, societal structures, cultures, underlying world-views and the paradigmatic potential of CE remain largely unexplored".[66]

It is also often pointed out that there are fundamental limits to the concept, which are based, among other things, on the laws of thermodynamics. According to the second law of thermodynamics, all spontaneous processes are irreversible and associated with an increase in entropy. It follows that in a real implementation of the concept, one would either have to deviate from the perfect reversibility in order to generate an entropy increase by generating waste, which would ultimately amount to still having parts of the economy which follow a linear scheme, or enormous amounts of energy would be required (from which a significant part would be dissipated in order to for the total entropy to increase).[67] In its comment to concept of the circular economy the European Academies' Science Advisory Council (EASAC) came to a similar conclusion:

Recovery and recycling of materials that have been dispersed through pollution, waste and end-of-life product disposal require energy and resources, which increase in a nonlinear manner as the percentage of recycled material rises (owing to the second law of thermodynamics: entropy causing dispersion). Recovery can never be 100% (Faber et al., 1987). The level of recycling that is appropriate may differ between materials.[68]

Industries adopting a circular economy

Textile industry

A circular economy within the textiles industry refers to the practice of clothes and fibers continually being recycled, to re-enter the economy as much as possible rather than ending up as waste.

A circular textiles economy is in response to the current linear model of the fashion industry, "in which raw materials are extracted, manufactured into commercial goods and then bought, used and eventually discarded by consumers" (Business of Fashion, 2017).[69] 'Fast fashion 'companies have fueled the high rates of consumption which further magnify the issues of a linear system. "The take-make-dispose model not only leads to an economic value loss of over $500 billion per year but also has numerous negative environmental and societal impacts" (Business of Fashion, 2018).[70] Such environmental effects include tons of clothing ending up in landfills and incineration, while the societal effects put human rights at risk. A documentary about the world of fashion, The True Cost (2015),[71] explained that in fast fashion, "wages, unsafe conditions, and factory disasters are all excused because of the needed jobs they create for people with no alternatives." This shows that fast fashion is harming the planet in more ways than one by running on a linear system.

It is argued that by following a circular economy, the textile industry can be transformed into a sustainable business. A 2017 report, "A New Textiles Economy",[72] stated the four key ambitions needed to establish a circular economy: "phasing out substances of concern and microfiber release; transforming the way clothes are designed, sold and used to break free from their increasingly disposable nature; radically improving recycling by transforming clothing design, collection, and reprocessing; and making effective use of resources and moving to renewable input." While it may sound like a simple task, only a handful of designers in the fashion industry have taken charge, including Patagonia, Eileen Fisher, and Stella McCartney. An example of a circular economy within a fashion brand is Eileen Fisher's Tiny Factory, in which customers are encouraged to bring their worn clothing to be manufactured and resold. In a 2018 interview,[73] Fisher explained, "A big part of the problem with fashion is overconsumption. We need to make less and sell less ... you get to use your creativity but you also get to sell more but not create more stuff."

Circular initiatives, such as clothing rental startups, are also getting more and more highlight in the EU and in the US as well. Operating with circular business model, rental services offer everyday fashion, baby wear, maternity wear for rent. The companies either offer flexible pricing in a 'pay as you rent' model like Palanta does,[74] or offer fixed monthly subscriptions such as Rent The Runway or Le Tote.

Another circular initiative is offering a take-back program. A company located in Colorado Circular Threads repurposes post-consumer waste materials such as old denim jeans, retired climbing rope, and discarded sails into new products, rather than letting them go to a landfill. Their take back program allows the consumer to return any product at any time so that it can be recycled again.[75]

Both China and Europe have taken the lead in pushing a circular economy. The Journal of Industrial Ecology (2017)[76] stated that the "Chinese perspective on the circular economy is broad, incorporating pollution and other issues alongside waste and resource concerns, [while] Europe's conception of the circular economy has a narrower environmental scope, focusing on waste and resources and opportunities for business".

Construction industry

The construction sector is one of the world's largest waste generators. The circular economy appears as a helpful solution to diminish the environmental impact of the industry.

Construction is very important to the economy of the European Union and its state members. It provides 18 million direct jobs and contributes to about 9% of the EU's GDP.[77] The main causes of the construction's environmental impact are found in the consumption of non-renewable resources and the generation of contaminant residues, both of which are increasing at an accelerating pace.[78]

Decision making about the circular economy can be performed on the operational (connected with particular parts of the production process), tactical (connected with whole processes) and strategic (connected with the whole organization) levels. It may concern both construction companies as well as construction projects (where a construction company is one of the stakeholders).

End-of-life buildings can be deconstructed, hereby creating new construction elements that can be used for creating new buildings and freeing up space for new development.

Modular construction systems can be useful to create new buildings in the future, and have the advantage of allowing easier deconstruction and reuse of the components afterwards (end-of-life buildings).

Another example that fits the idea of circular economy in the construction sector on the operational level, there can be pointed walnut husks, that belong to hard, light and natural abrasives used for example in cleaning brick surfaces. Abrasive grains are produced from crushed, cleaned and selected walnut shells. They are classified as reusable abrasives. A first attempt to measure the success of circular economy implementation was done in a construction company.[79] The circular economy can contribute to creating new posts and economic growth.[80] According to Gorecki,[81] one of such posts may be the Circular economy manager employed for construction projects.

Automotive industry

The circular economy is beginning to catch on inside the automotive industry.[82] There are also incentives for carmakers to do so as a 2016 report by Accenture stated that the circular economy could redefine competitiveness in the automotive sector in terms of price, quality, and convenience and could double revenue by 2030 and lower the cost base by up to fourteen percent. So far, it has typically translated itself into using parts made from recycled materials,[83] remanufacturing of car parts and looking at the design of new cars.[84][85] With the vehicle recycling industry (in the EU) only being able to recycle just 75% of the vehicle, meaning 25% isn't recycled and may even end up in landfills,[86] there is much to improve here. In the electric vehicle industry, disassembly robots are used to help disassemble the vehicle.[87] In the EU's ETN-Demeter project (European Training Network for the Design and Recycling of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motors and Generators in Hybrid and Full Electric Vehicles)[88] they are looking at the sustainable design issue. They are for example making designs of electric motors of which the magnets can be easily removed for recycling the rare earth metals.

Some car manufacturers such as Volvo are also looking at alternative ownership models (leasing from the automotive company; "Care by Volvo").[89]

Logistics industry

The logistics industry plays an important role in the Dutch economy because the Netherlands is located in a specific area where the transit of commodities takes place on a daily basis. The Netherlands is an example of a country from the EU that has increasingly moved towards incorporating a circular economy given the vulnerability of the Dutch economy (as well as other EU countries) to be highly dependable on raw materials imports from countries such as China, which makes the country susceptible to the unpredictable importation costs for such primary goods.[90]

Research related to the Dutch industry shows that 25% of the Dutch companies are knowledgeable and interested in a circular economy; furthermore, this number increases to 57% for companies with more than 500 employees. Some of the areas are chemical industries, wholesale trade, industry and agriculture, forestry and fisheries because they see a potential reduction of costs when reusing, recycling and reducing raw materials imports. In addition, logistic companies can enable a connection to a circular economy by providing customers incentives to reduce costs through shipment and route optimization, as well as, offering services such as prepaid shipping labels, smart packaging, and take-back options.[90] The shift from linear flows of packaging to circular flows as encouraged by the circular economy is critical for the sustainable performance and reputation of the packaging industry.[30] The government-wide program for a circular economy is aimed at developing a circular economy in the Netherlands by 2050.[91]

Several statistics have indicated that there will be an increase in freight transport worldwide, which will affect the environmental impacts of the global warming potential causing a challenge to the logistics industry, however, the Dutch council for the Environment and Infrastructure (Dutch acronym: Rli) provided a new framework in which it suggests that the logistics industry can provide other ways to add value to the different activities in the Dutch economy, such as, an exchange of resources (either waste or water flows) for production from the different industries, in addition, to change the transit port concept to a transit hub. Moreover, the Rli studied the role of the logistics industry for three sectors, agriculture and food, chemical industries and high tech industries.[90]

Agriculture

The Netherlands, aiming to have a completely circular economy by 2050,[92] has also foreseen a shift to circular agriculture (kringlooplandbouw[93]) as part of this plan. This shift foresees having a "sustainable and strong agriculture" by as early as 2030.[94][95] Changes in the Dutch laws and regulations will be introduced. Some key points in this plant include:

- closing the fodder-manure cycle

- reusing as much waste streams as possible (a team Reststromen will be appointed)

- reducing the use of artificial fertilizers in favor of natural manure

- providing the chance for farms within experimentation areas to deviate from law and regulations

- implementing uniform methods to measure the soil quality

- providing the opportunity to agricultural entrepreneurs to sign an agreement with the Staatsbosbeheer ("State forest management") to have it use the lands they lease for natuurinclusieve landbouw ("nature-inclusive management")

- providing initiatives to increase the earnings of farmers

Furniture industry

When it comes to the furniture industry, most of the products are passive durable products, and accordingly implementing strategies and business models that extend the lifetime of the products (like repairing and remanufacturing) would usually have lower environmental impacts and lower costs.[96] Companies such as GGMS are supporting a circular approach to furniture by refurbishing and reupholstering items for reuse. [97]

The EU has seen a huge potential for implementing a circular economy in the furniture sector. Currently, out of 10,000,000 tonnes of annually discarded furniture in the EU, most of it ends up in landfills or is incinerated. There is a potential increase of €4.9 billion in Gross Value Added by switching to a circular model by 2030, and 163,300 jobs could be created.[98]

A study about the status of Danish furniture companies' efforts on a circular economy states that 44% of the companies included maintenance in their business models, 22% had take-back schemes, and 56% designed furniture for recycling. The authors of the study concluded that although a circular furniture economy in Denmark is gaining momentum, furniture companies lack knowledge on how to effectively transition, and the need to change the business model could be another barrier.[99]

Another report in the UK saw a huge potential for reuse and recycling in the furniture sector. The study concluded that around 42% of the bulk waste sent to landfills annually (1.6 million tonnes) is furniture. They also found that 80% of the raw material in the production phase is waste.

Oil and gas industry

The uptake to reuse within the oil and gas industry is very poor, the opportunity to reuse is never more evident, or possible, as when the equipment is being decommissioned.[4] Hundreds of thousands of tons of waste are being brought back onshore to be recycled. Unfortunately, what this equates to; is equipment, which is perfectly suitable for continued use, being disposed of.[100]

In the next 30–40 years, the oil and gas sector will have to decommission 600 installations in the UK alone. Over the next decade around 840,000 tonnes of materials will have to be recovered at an estimated cost of £25Bn. In 2017 North Sea oil and gas decommissioning became a net drain on the public purse. With UK taxpayers covering 50%–70% of the bill, there is an urgent need to discuss the most economic, social and environmentally beneficial decommissioning solutions for the general public.[101]

Organizations such as Zero Waste Scotland have conducted studies to identify areas with reuse potential, allowing equipment to continue life in other industries, or be redeployed for oil and gas .[102]

Strategic management and the circular economy

The CE does not aim at changing the profit maximization paradigm of businesses. Rather, it suggests an alternative way of thinking how to attain a sustained competitive advantage (SCA), while concurrently addressing the environmental and socio-economic concerns of the 21st century. Indeed, stepping away from linear forms of production most often leads to the development of new core competencies along the value chain and ultimately superior performance that cuts costs, improves efficiency, meets advanced government regulations and the expectations of green consumers. But despite the multiple examples of companies successfully embracing circular solutions across industries, and notwithstanding the wealth of opportunities that exist when a firm has clarity over what circular actions fit its unique profile and goals, CE decision-making remains a highly complex exercise with no one-size-fits-all solution. The intricacy and fuzziness of the topic is still felt by most companies (especially SMEs), which perceive circular strategies as something not applicable to them or too costly and risky to implement.[103] This concern is today confirmed by the results of ongoing monitoring studies like the Circular Readiness Assessment.[104]

Strategic management is the field of management that comes to the rescue allowing companies to carefully evaluate CE-inspired ideas, but also to take a firm apart and investigate if/how/where seeds of circularity can be found or implanted. The book Strategic Management and the Circular Economy defined for the first time a CE strategic decision-making process, covering the phases of analysis, formulation, and planning. Each phase is supported by frameworks and concepts popular in management consulting – like idea tree, value chain, VRIE, Porter's five forces, PEST, SWOT, strategic clock, or the internationalization matrix – all adapted through a CE lens, hence revealing new sets of questions and considerations. Although yet to be verified, it is argued that all standard tools for strategic management can and should be calibrated and applied to a CE. A specific argument has already been made for the strategy direction matrix of product vs market and the 3 × 3 GE-McKinsey matrix to assess business strength vs industry attractiveness, the BCG matrix of market share vs industry growth rate, and Kraljic's portfolio matrix.[105]

Impact in Europe

On 17 December 2012, the European Commission published a document entitled "Manifesto for a Resource Efficient Europe". This manifesto clearly stated that "In a world with growing pressures on resources and the environment, the EU has no choice but to go for the transition to a resource-efficient and ultimately regenerative circular economy."[106] Furthermore, the document highlighted the importance of "a systemic change in the use and recovery of resources in the economy" in ensuring future jobs and competitiveness, and outlined potential pathways to a circular economy, in innovation and investment, regulation, tackling harmful subsidies, increasing opportunities for new business models, and setting clear targets.

The European environmental research and innovation policy aims at supporting the transition to a circular economy in Europe, defining and driving the implementation of a transformative agenda to green the economy and the society as a whole, to achieve a truly sustainable development. Research and innovation in Europe are financially supported by the program Horizon 2020, which is also open to participation worldwide.[107] Circular economy is found to play an important role to economic growth of European Countries, highlighting the crucial role of sustainability, innovation, and investment in no-waste initiatives to promote wealth.[108]

The European Union plans for a circular economy are spearheaded by its 2018 Circular Economy Package.[109] Historically, the policy debate in Brussels mainly focused on waste management which is the second half of the cycle, and very little is said about the first half: eco-design. To draw the attention of policymakers and other stakeholders to this loophole, the Ecothis, an EU campaign was launched raising awareness about the economic and environmental consequences of not including eco-design as part of the circular economy package.

In 2020, the European Union released its Circular Economy Action Plan.[110]

Related concepts

The various approaches to 'circular' business and economic models share several common principles with other conceptual frameworks:

Biomimicry

Janine Benyus, author of "Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature", defined Biomimicry as "a new discipline that studies nature's best ideas and then imitates these designs and processes to solve human problems. Studying a leaf to invent a better solar cell is an example. I think of it as 'innovation' inspired by nature".[111]

Blue economy

Initiated by former Ecover CEO and Belgian entrepreneur Gunter Pauli, derived from the study of natural biological production processes the official manifesto states, "using the resources available...the waste of one product becomes the input to create a new cash flow".[112]

Cradle to cradle

Created by Walter R. Stahel and similar theorists, in which industry adopts the reuse and service-life extension of goods as a strategy of waste prevention, regional job creation, and resource efficiency in order to decouple wealth from resource consumption.[113][114]

Industrial ecology

Industrial Ecology is the study of material and energy flows through industrial systems. Focusing on connections between operators within the "industrial ecosystem", this approach aims at creating closed-loop processes in which waste is seen as input, thus eliminating the notion of undesirable by-product.[115]

Resource recovery

Resource recovery is using wastes as an input material to create valuable products as new outputs. The aim is to reduce the amount of waste generated, therefore reducing the need for landfill space and also extracting maximum value from waste.

Systems thinking

The ability to understand how things influence one another within a whole. Elements are considered as 'fitting in' their infrastructure, environment and social context.

"The Biosphere Rules"

The Biosphere Rules is a framework for implementing closed-loop production processes. They derived from nature systems and translated for industrial production systems. The five principles are Materials Parsimony, Value Cycling, Power Autonomy, Sustainable Product Platforms and Function Over Form.

See also

- Appropriate technology

- BlueCity

- Container-deposit legislation

- Digital Product Passport

- Downcycling

- Durable good

- European Green Deal

- Food vs. feed

- Government by algorithm

- Green economy

- Life cycle assessment

- Life cycle thinking

- List of environment topics

- Loop analysis

- Path analysis (statistics)

- Reuse

- Sharing economy

- Social metabolism

- Synthetic fuels

- Sustainable Product Policy Initiative

- Upcycling

- Waste & Resources Action Programme

References

- Geissdoerfer, M., Pieroni, M.P., Pigosso, D.C. and Soufani, K. "Circular business models: A review" (PDF). Journal of Cleaner Production. 277: 123741.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Circularity Indicators". www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org. Retrieved 2019-03-14.

- Geissdoerfer, Martin; Savaget, Paulo; Bocken, Nancy M. P.; Hultink, Erik Jan (2017-02-01). "The Circular Economy – A new sustainability paradigm?". Journal of Cleaner Production. 143: 757–768. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.048. S2CID 157449142.

- Invernizzi, Diletta Colette; Locatelli, Giorgio; Velenturf, Anne; Love, Peter ED.; Purnell, Phil; Brookes, Naomi J. (2020-09-01). "Developing policies for the end-of-life of energy infrastructure: Coming to terms with the challenges of decommissioning". Energy Policy. 144: 111677. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111677. ISSN 0301-4215.

- Towards the Circular Economy: an economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2012. p. 24. Archived from the original on 2013-01-10. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- Hysa, E.; Kruja, A.; Rehman, N.U.; Laurenti, R. Circular Economy Innovation and Environmental Sustainability Impact on Economic Growth: An Integrated Model for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4831., https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/12/4831

- Ranta, Valtteri; Aarikka-Stenroos, Leena; Ritala, Paavo; Mäkinen, Saku J. (August 2018). "Exploring institutional drivers and barriers of the circular economy: A cross-regional comparison of China, the US, and Europe". Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 135: 70–82. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.08.017.

- Murray, Alan; Skene, Keith; Haynes, Kathryn (2015-05-22). "The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context". Journal of Business Ethics. 140 (3): 369–380. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2693-2. ISSN 0167-4544. S2CID 41486703.

- Kaur, Guneet; Uisan, Kristiadi; Lun Ong, Khai; Sze Ki Lin, Carol (2017). "Recent trend in Green sustainable Chemistry & waste valorisation: Rethinking plastics in a circular economy". Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry. 9: 30–39. doi:10.1016/j.cogsc.2017.11.003.

- Casarejos, Fabricio; Bastos, Claudio R.; Rufin, Carlos; Frota, Mauricio N. (November 2018). "Rethinking packaging production and consumption vis-à-vis circular economy: A case study of compostable cassava starch-based material". Journal of Cleaner Production. 201: 1019–1028. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.114. ISSN 0959-6526.

- Mignacca, Benito; Locatelli, Giorgio; Velenturf, Anne (26 Feb 2020). "Modularisation as enabler of circular economy in energy infrastructure". Energy Policy. 139: 111371. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111371.

- Boulding, Kenneth E. (March 8, 1966). "The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth" (PDF). In H. Jarrett (ed.) Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy, Resources for the Future, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, pp. 3-14. Retrieved 26 August 2018, or dieoff.org Archived 2019-04-16 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- Allwood, Julian M. (2014). "Squaring the Circular Economy". Handbook of Recycling. pp. 445–477. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-396459-5.00030-1. ISBN 9780123964595. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - David W. Pearce and R. Kerry Turner (1989). Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801839870.

- Su, Biwei; Heshmati, Almas; Geng, Yong; Yu, Xiaoman (2012). "A review of the circular economy in China: moving from rhetoric to implementation". Journal of Cleaner Production. 42: 215–227. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.020.

- Jackson, Tim (1993). Clean Production Strategies Developing Preventive Environmental Management in the Industrial Economy. https://www.crcpress.com/Clean-Production-Strategies-Developing-Preventive-Environmental-Management/Jackson/p/book/9780873718844: CRC Press. ISBN 9780873718844.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Jackson, Tim (1996). Material Concerns — Pollution, Profit and Quality of Life. https://www.routledge.com/Material-Concerns-Pollution-Profit-and-Quality-of-Life/Jackson/p/book/9780415132497: Routledge.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Cradle to Cradle | The Product-Life Institute". Product-life.org. 2012-11-14. Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- Clift & Allwood, "Rethinking the economy", The Chemical Engineer, March 2011

- Zhijun, F; Nailing, Y (2007). "Putting a circular economy into practice in China" (PDF). Sustain Sci. 2: 95–101. doi:10.1007/s11625-006-0018-1. S2CID 29150129.

- "The Ellen MacArthur Foundation website". Ellenmacarthurfoundation.org. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- Blok, Kornelis; Hoogzaad, Jelmer; Ramkumar, Shyaam; Ridley, Shyaam; Srivastav, Preeti; Tan, Irina; Terlouw, Wouter; de Wit, Terlouw. "Implementing Circular Economy Globally Makes Paris Targets Achievable". Circle Economy. Circle Economy, Ecofys. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition (PDF) (Report). Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2013. Retrieved 2020-05-15. And: Towards the Circular Economy: an economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2012. p. 60. Archived from the original on 2013-01-10. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- Estimating Employment Effects of the Circular Economy

- Scott, W. Richard (2008). Institutions and Organization: Ideas and Interest (Third ed.). Stanford University: Sage Publications. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-1-4129-5090-9.

- Republic Services. "Republic Services Annual Report 2017" (PDF). annualreports.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Geissdoerfer, Martin; Morioka, Sandra Naomi; de Carvalho, Marly Monteiro; Evans, Steve (April 2018). "Business models and supply chains for the circular economy". Journal of Cleaner Production. 190: 712–721. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.159. ISSN 0959-6526. S2CID 158887458.

- Rashid, Amir; Asif, Farazee M.A.; Krajnik, Peter; Nicolescu, Cornel Mihai (Oct 2013). "Resource Conservative Manufacturing: an essential change in business and technology paradigm for sustainable manufacturing". Journal of Cleaner Production. 57: 166–177. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.06.012. ISSN 0959-6526.

- "Solutions". solve.mit.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- Batista, Luciano; Gong, Yu; Pereira, Susana; Jia, Fu; Bittar, Alexandre (December 2019). "Circular supply chains in emerging economies – a comparative study of packaging recovery ecosystems in China and Brazil" (PDF). International Journal of Production Research. 57 (23): 7248–7268. doi:10.1080/00207543.2018.1558295. S2CID 116320263.

- Weetman, Catherine (2016). A circular economy handbook for business and supply chains : repair, remake, redesign, rethink. London, United Kingdom: Kogan Page. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-74947675-5. OCLC 967729002.

- Kristoffersen, Eivind; Blomsma, Fenna; Mikalef, Patrick; Li, Jingyue (2020-11-01). "The smart circular economy: A digital-enabled circular strategies framework for manufacturing companies". Journal of Business Research. 120: 241–261. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.07.044. ISSN 0148-2963.

- "Intelligent Assets: Unlocking the circular economy potential, by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and World Economic Forum as part of Project MainStream". www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "How to transition to a digital circular economy?". G-STIC. 2020-10-28. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "New Circular Economy Strategic R&I Agenda now available". CICERONE. 2020-09-27. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "Home". PACE. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- Hub, IISD's SDG Knowledge. "WEF Launches Public-Private Platform on Circular Economy | News | SDG Knowledge Hub | IISD". Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "Circular Economy". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- Hub, IISD's SDG Knowledge. "WEF Launches Public-Private Platform on Circular Economy | News | SDG Knowledge Hub | IISD". Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "The Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE)". Sitra. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "The world is now only 8.6% circular - CGR 2020 - Circularity Gap Reporting Initiative". www.circularity-gap.world. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- "Circular Gap Report 2020" (PDF).

- "Members". Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "WEF PACE pdf" (PDF).

- "Philips delivers on commitment to the circular economy at DAVOS 2019". Philips. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "Capital Equipment Coalition". Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "The Capital Equipment Pledge". The Capital Equipment Pledge. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "Global Battery Alliance". Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "Global Battery Alliance". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "A New Circular Vision for Electronics" (PDF).

- "A New Circular Vision for Electronics: Time for a global reboot". Green Growth Knowledge Platform. 2019-02-10. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "Team". PACE. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- "RELEASE: PACE Welcomes David McGinty as Global Director". World Resources Institute. 2019-05-16. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- "Members". PACE. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- "Developing BS 8001 - a world first". The British Standards Institution. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Pauliuk, Stefan (2018). "Critical appraisal of the circular economy standard BS 8001:2017 and a dashboard of quantitative system indicators for its implementation in organizations". Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 129: 81–92. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.10.019. ISSN 0921-3449.

- "ISO/TC 323 - Circular economy". ISO. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- Corvellec, Hervé. (2015). "New directions for management and organization studies on waste". Technical report. Göteborg: Gothenburg Research Institute, University of Gothenburg.

- Corvellec, Hervé (2019). "Waste as scats: For an organizational engagement with waste". Organization, 26(2), 217–235. doi:10.1177/1350508418808235

- Corvellec, H., & Stål, H. I. (2019). "Qualification as corporate activism: How Swedish apparel retailers attach circular fashion qualities to take-back systems". Scandinavian Journal of Management, 35(3), 101046. doi:10.1016/j.scaman.2019.03.002

- Zink, T., & Geyer, R. (2017). "Circular economy rebound". Journal of Industrial Ecology, 21(3), 593–602. doi:10.1111/jiec.12545

- Lazarevic, D., & Valve, H. (2017). "Narrating expectations for the circular economy: Towards a common and contested European transition". Energy Research & Social Science, 31, 60–69. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.006

- Valenzuela, F., & Böhm, S. (2017). "Against wasted politics: A critique of the circular economy" ephemera: theory & politics in organization, 17(1), 23-60.

- Allwood, J. M. (2014). "Squaring the circular economy: The role of recycling within a hierarchy of material management strategies". In Handbook of recycling: State-of-the-art for practitioners, analysts, and scientists, edited by E. Worrell and M. Reuter. Waltham, MA, USA: Elsevier, page 446. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-396459-5.00030-1

- McMillan, C. A., S. J. Skerlos, and G. A. Keoleian (2012). "Evaluation of the metals industry's position on recycling and its implications for environmental emissions". Journal of Industrial Ecology 16(3): 324–333. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00483.x

- Korhonen, J., Nuur, C., Feldmann, A., & Birkie, S. E. (2018). "Circular economy as an essentially contested concept". Journal of Cleaner Production, 175, 544–552. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.111

- Korhonen, Jouni; Honkasalo, Antero; Seppälä, Jyri (2018-01-01). "Circular Economy: The Concept and its Limitations". Ecological Economics. 143: 37–46. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.06.041. ISSN 0921-8009.

- "Circular economy: a commentary from the perspectives of the natural and social sciences" (PDF). European Academies' Science Advisory Council (EASAC).

- "In Copenhagen, Gearing up for a Circular Fashion System". The Business of Fashion. 2017-05-11. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- "Dame Ellen MacArthur on Building Momentum for Sustainability in Fashion". The Business of Fashion. 2018-01-11. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- Ross, M (Producer), & Morgan, A (Director). (2015, May). The true cost [Motion Picture]. United States: Life is My Movie Entertainment.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation, A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion's future, (2017, http://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications).

- The Glossy Podcast. (2018, May 30). Eileen Fisher on 34 years in sustainable fashion: "It's about constantly learning" [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from https://theglossypodcast.libsyn.com/.

- "how PALANTA works". palanta.co. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- https://circularthreads.com/pages/about-us

- McDowall, W. & Geng, Y. (2017, June). Circular economy policies in China and Europe. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 21 (3).

- "Construction | Growth". European Commission. 2016-07-05. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Nuñez-Cacho, Pedro; Górecki, Jarosław; Molina-Moreno, Valentin; Corpas-Iglesias, Francisco Antonio (2018). "New Measures of Circular Economy Thinking in Construction Companies". Journal of EU Research in Business. 2018: 1–16. doi:10.5171/2018.909360.

- Nuñez-Cacho, Pedro; Górecki, Jarosław; Molina-Moreno, Valentín; Corpas-Iglesias, Francisco Antonio (2018). "What Gets Measured, Gets Done: Development of a Circular Economy Measurement Scale for Building Industry". Sustainability. 10(7) (2340): 2340. doi:10.3390/su10072340.

- Górecki, Jarosław; Nuñez-Cacho, Pedro; Corpas-Iglesias, Francisco Antonio; Molina-Moreno, Valentin (2019). "How to convince players in construction market? Strategies for effective implementation of circular economy in construction sector". Cogent Engineering. 6 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/23311916.2019.1690760.

- Górecki, Jarosław (2020). "Simulation-Based Positioning of Circular Economy Manager's Skills in Construction Projects". Symmetry. 12 (1): 50. doi:10.3390/sym12010050.

- European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform

- Automakers Enter the Circular Economy

- The Circular Economy In The Automotive Sector: How Far Can We Introduce It?

- The Circular Economy Applied to the Automotive Industry

- End-of-Life Vehicle Recycling in the European Union

- Robot-Assisted Disassembly for the Recycling of Electric Vehicle Batteries

- "DEMETER project". etn-demeter.eu.

- [https://medium.com/@ECONYL/riding-the-wave-of-change-in-the-automotive-industry-with-circular-economy-5c0428df5cc2 Riding the wave of change in the automotive industry with circular economy

- van Buren, Nicole; Demmers, Marjolein; van der Heijden, Rob; Witlox, Frank (8 July 2016). "Towards a Circular Economy: The Role of Dutch Logistics Industries and Governments". Sustainability. 8 (7): 647. doi:10.3390/su8070647.

- Zaken, Ministerie van Algemene (2016-09-14). "A Circular Economy in the Netherlands by 2050 - Policy note - Government.nl". www.government.nl. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- Circulair Nederland 2050

- Kringlooplandbouw

- Omslag naar duurzame en sterke landbouw definitief ingezet

- Realisatieplan Visie LNV: Op weg met nieuw perspectief

- Kaddoura, Mohamad; Kambanou, Marianna Lena; Tillman, Anne-Marie; Sakao, Tomohiko (2019). "Is Prolonging the Lifetime of Passive Durable Products a Low-Hanging Fruit of a Circular Economy? A Multiple Case Study". Sustainability. 11 (18): 4819. doi:10.3390/su11184819.

- "Circular economy 101". 2020-10-06.

- "Furn 360 Project | Circular Economy in furniture sectors".

- "Circular economy in the Danish furniture sector". 2018-12-19.

- "About Legasea".

- "New project to apply circular economy to oil and gas decommissioning". 2019-07-24.

- "North sea oil and gas rig decommissioning & re-use opportunity report". 2015-10-08.

- Cristoni, Nicolò and Marcello Tonelli (2018). "Perceptions of Firms Participating in a Circular Economy." European Journal of Sustainable Development 7(4): 105-18. doi: 10.14207/ejsd.2018.v7n4p105

- "Circular Readiness Assessment website" http://www.worldynamics.com/circular_economy/web/assessment/main Retrieved on 26 July 2018

- Tonelli Marcello and Nicolo Cristoni (2018). Strategic Management and the Circular Economy. https://www.amazon.com/Strategic-Management-Circular-Routledge-Research/dp/1138103632 New York: Routledge.

- "Manifesto for a Resource Efficient Europe". European Commission. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- See Horizon 2020 – the EU's new research and innovation programme: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-13-1085_en.htm

- Hysa, E.; Kruja, A.; Rehman, N.U.; Laurenti, R. Circular Economy Innovation and Environmental Sustainability Impact on Economic Growth: An Integrated Model for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4831., https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/12/4831/htm

- "Circular Economy Strategy – Environment – European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- Circular economy action plan text

- "What is Biomimicry?". Biomimicry Institute. Archived from the original on 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- "Blue Economy : Green Economy 2.0". Blueeconomy.de. Retrieved 2013-11-20. (see: www.theblueeconomy.org)

- Zhong, Shan (2018). "Tightening the loop on the circular economy: Coupled distributed recycling and manufacturing with recyclebot and RepRap 3-D printing" (PDF). Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 128: 48–58. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.023.

- Cooper, Tim (2005). "Slower Consumption Reflections on Product Life Spans and the "Throwaway Society"" (PDF). Journal of Industrial Ecology. 9 (1–2): 51–67. doi:10.1162/1088198054084671.

- "International Society for Industrial Ecology – Home". Is4ie.org. Retrieved 2013-11-20.