Efficient energy use

Efficient energy use, sometimes simply called energy efficiency, is the goal to reduce the amount of energy required to provide products and services. For example, insulating a building allows it to use less heating and cooling energy to achieve and maintain a thermal comfort. Installing light-emitting diode bulbs, fluorescent lighting, or natural skylight windows reduces the amount of energy required to attain the same level of illumination compared to using traditional incandescent light bulbs. Improvements in energy efficiency are generally achieved by adopting a more efficient technology or production process[1] or by application of commonly accepted methods to reduce energy losses.

| Part of a series about |

| Sustainable energy |

|---|

|

| Overview |

| Energy conservation |

| Renewable energy |

| Sustainable transport |

|

There are many motivations to improve energy efficiency. Decreasing energy use reduces energy costs and may result in a financial cost saving to consumers if the energy savings offset any additional costs of implementing an energy-efficient technology. Reducing energy use is also seen as a solution to the problem of minimizing greenhouse gas emissions. According to the International Energy Agency, improved energy efficiency in buildings, industrial processes and transportation could reduce the world's energy needs in 2050 by one third, and help control global emissions of greenhouse gases.[2] Another important solution is to remove government-led energy subsidies that promote high energy consumption and inefficient energy use in more than half of the countries in the world.[3]

Energy efficiency and renewable energy are said to be the twin pillars of sustainable energy policy[4] and are high priorities in the sustainable energy hierarchy. In many countries energy efficiency is also seen to have a national security benefit because it can be used to reduce the level of energy imports from foreign countries and may slow down the rate of energy at which domestic energy resources are depleted.

Overview

Energy efficiency has proved to be a cost-effective strategy for building economies without necessarily increasing energy consumption. For example, the state of California began implementing energy-efficiency measures in the mid-1970s, including building code and appliance standards with strict efficiency requirements. During the following years, California's energy consumption has remained approximately flat on a per capita basis while national US consumption doubled.[5] As part of its strategy, California implemented a "loading order" for new energy resources that puts energy efficiency first, renewable electricity supplies second, and new fossil-fired power plants last.[6] States such as Connecticut and New York have created quasi-public Green Banks to help residential and commercial building-owners finance energy efficiency upgrades that reduce emissions and cut consumers' energy costs.[7]

Lovin's Rocky Mountain Institute points out that in industrial settings, "there are abundant opportunities to save 70% to 90% of the energy and cost for lighting, fan, and pump systems; 50% for electric motors; and 60% in areas such as heating, cooling, office equipment, and appliances." In general, up to 75% of the electricity used in the US today could be saved with efficiency measures that cost less than the electricity itself, the same holds true for home settings. The US Department of Energy has stated that there is potential for energy saving in the magnitude of 90 Billion kWh by increasing home energy efficiency.[8]

Other studies have emphasized this. A report published in 2006 by the McKinsey Global Institute, asserted that "there are sufficient economically viable opportunities for energy-productivity improvements that could keep global energy-demand growth at less than 1 percent per annum"—less than half of the 2.2 percent average growth anticipated through 2020 in a business-as-usual scenario.[9] Energy productivity, which measures the output and quality of goods and services per unit of energy input, can come from either reducing the amount of energy required to produce something, or from increasing the quantity or quality of goods and services from the same amount of energy.

The Vienna Climate Change Talks 2007 Report, under the auspices of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, clearly shows "that energy efficiency can achieve real emission reductions at low cost."[10]

International standards ISO 17743 and ISO 17742 provide a documented methodology for calculating and reporting on energy savings and energy efficiency for countries and cities.[11][12]

The energy intensity of a country or region, the ratio of energy use to Gross Domestic Product or some other measure of economic output", differs from its energy efficiency. Energy intensity is affected by climate, economic structure (e.g. services vs manufacturing), trade, as well as the energy efficiency of buildings, vehicles, and industry. [13]

Benefits

From the point of view of an energy consumer, the main motivation of energy efficiency is often simply saving money by lowering the cost of purchasing energy. Additionally, from an energy policy point of view, there has been a long trend in a wider recognition of energy efficiency as the "first fuel", meaning the ability to replace or avoiod the consumption of actual fuels. In fact, International Energy Agency has calculated that the application of energy efficiency measures in the years 1974-2010 has succeeded in avoiding more energy consumption in its member states than is the consumption of any particular fuel, including oil, coal and natural gas.[14]

Moreover, it has long been recognized that energy efficiency brings other benefits additional to the reduction of energy consumption.[15] Some estimates of the value of these other benefits, often called multiple benefits, co-benefits, ancillary benefits or non-energy benefits, have put their summed value even higher than that of the direct energy benefits.[16] These multiple benefits of energy efficiency include things such as reduced climate change impact, reduced air pollution and improved health, improved indoor conditions, improved energy security and reduction of the price risk for energy consumers. Methods for calculating the monetary value of these multiple benefits have been developed, including e.g. the choice experiment method for improvements that have a subjective component (such as aesthetics or comfort)[14] and Tuominen-Seppänen method for price risk reduction.[17][18] When included in the analysis, the economic benefit of energy efficiency investments can be shown to be significantly higher than simply the value of the saved energy.[14]

Appliances

Modern appliances, such as, freezers, ovens, stoves, dishwashers, clothes washers and dryers, use significantly less energy than older appliances. Installing a clothesline will significantly reduce one's energy consumption as their dryer will be used less. Current energy-efficient refrigerators, for example, use 40 percent less energy than conventional models did in 2001. Following this, if all households in Europe changed their more than ten-year-old appliances into new ones, 20 billion kWh of electricity would be saved annually, hence reducing CO2 emissions by almost 18 billion kg.[19] In the US, the corresponding figures would be 17 billion kWh of electricity and 27,000,000,000 lb (1.2×1010 kg) CO2.[20] According to a 2009 study from McKinsey & Company the replacement of old appliances is one of the most efficient global measures to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases.[21] Modern power management systems also reduce energy usage by idle appliances by turning them off or putting them into a low-energy mode after a certain time. Many countries identify energy-efficient appliances using energy input labeling.[22]

The impact of energy efficiency on peak demand depends on when the appliance is used. For example, an air conditioner uses more energy during the afternoon when it is hot. Therefore, an energy-efficient air conditioner will have a larger impact on peak demand than off-peak demand. An energy-efficient dishwasher, on the other hand, uses more energy during the late evening when people do their dishes. This appliance may have little to no impact on peak demand.

Building design

Buildings are an important field for energy efficiency improvements around the world because of their role as a major energy consumer. However, the question of energy use in buildings is not straightforward as the indoor conditions that can be achieved with energy use vary a lot. The measures that keep buildings comfortable, lighting, heating, cooling and ventilation, all consume energy. Typically the level of energy efficiency in a building is measured by dividing energy consumed with the floor area of the building which is referred to as specific energy consumption or energy use intensity:[25]

However, the issue is more complex as building materials have embodied energy in them. On the other hand, energy can be recovered from the materials when the building is dismantled by reusing materials or burning them for energy. Moreover, when the building is used, the indoor conditions can vary resulting in higher and lower quality indoor environments. Finally, overall efficiency is affected by the use of the building: is the building occupied most of the time and are spaces efficiently used — or is the building largely empty? It has even been suggested that for a more complete accounting of energy efficiency, specific energy consumption should be amended to include these factors:[26]

Thus a balanced approach to energy efficiency in buildings should be more comprehensive than simply trying to minimize energy consumed. Issues such as quality of indoor environment and efficiency of space use should be factored in. Thus the measures used to improve energy efficiency can take many different forms. Often they include passive measures that inherently reduce the need to use energy, such as better insulation. Many serve various functions improving the indoor conditions as well as reducing energy use, such as increased use of natural light.

A building's location and surroundings play a key role in regulating its temperature and illumination. For example, trees, landscaping, and hills can provide shade and block wind. In cooler climates, designing northern hemisphere buildings with south facing windows and southern hemisphere buildings with north facing windows increases the amount of sun (ultimately heat energy) entering the building, minimizing energy use, by maximizing passive solar heating. Tight building design, including energy-efficient windows, well-sealed doors, and additional thermal insulation of walls, basement slabs, and foundations can reduce heat loss by 25 to 50 percent.[22][27]

Dark roofs may become up to 39 °C (70 °F) hotter than the most reflective white surfaces. They transmit some of this additional heat inside the building. US Studies have shown that lightly colored roofs use 40 percent less energy for cooling than buildings with darker roofs. White roof systems save more energy in sunnier climates. Advanced electronic heating and cooling systems can moderate energy consumption and improve the comfort of people in the building.[22]

Proper placement of windows and skylights as well as the use of architectural features that reflect light into a building can reduce the need for artificial lighting. Increased use of natural and task lighting has been shown by one study to increase productivity in schools and offices.[22] Compact fluorescent lamps use two-thirds less energy and may last 6 to 10 times longer than incandescent light bulbs. Newer fluorescent lights produce a natural light, and in most applications they are cost effective, despite their higher initial cost, with payback periods as low as a few months. LED lamps use only about 10% of the energy an incandescent lamp requires.

Effective energy-efficient building design can include the use of low cost passive infra reds to switch-off lighting when areas are unoccupied such as toilets, corridors or even office areas out-of-hours. In addition, lux levels can be monitored using daylight sensors linked to the building's lighting scheme to switch on/off or dim the lighting to pre-defined levels to take into account the natural light and thus reduce consumption. Building management systems link all of this together in one centralised computer to control the whole building's lighting and power requirements.[28]

In an analysis that integrates a residential bottom-up simulation with an economic multi-sector model, it has been shown that variable heat gains caused by insulation and air-conditioning efficiency can have load-shifting effects that are not uniform on the electricity load. The study also highlighted the impact of higher household efficiency on the power generation capacity choices that are made by the power sector.[29]

The choice of which space heating or cooling technology to use in buildings can have a significant impact on energy use and efficiency. For example, replacing an older 50% efficient natural gas furnace with a new 95% efficient one will dramatically reduce energy use, carbon emissions, and winter natural gas bills. Ground source heat pumps can be even more energy-efficient and cost-effective. These systems use pumps and compressors to move refrigerant fluid around a thermodynamic cycle in order to "pump" heat against its natural flow from hot to cold, for the purpose of transferring heat into a building from the large thermal reservoir contained within the nearby ground. The end result is that heat pumps typically use four times less electrical energy to deliver an equivalent amount of heat than a direct electrical heater does. Another advantage of a ground source heat pump is that it can be reversed in summertime and operate to cool the air by transferring heat from the building to the ground. The disadvantage of ground source heat pumps is their high initial capital cost, but this is typically recouped within five to ten years as a result of lower energy use.

Smart meters are slowly being adopted by the commercial sector to highlight to staff and for internal monitoring purposes the building's energy usage in a dynamic presentable format. The use of power quality analysers can be introduced into an existing building to assess usage, harmonic distortion, peaks, swells and interruptions amongst others to ultimately make the building more energy-efficient. Often such meters communicate by using wireless sensor networks.

Green Building XML is an emerging scheme, a subset of the Building Information Modeling efforts, focused on green building design and operation. It is used as input in several energy simulation engines. But with the development of modern computer technology, a large number of building performance simulation tools are available on the market. When choosing which simulation tool to use in a project, the user must consider the tool's accuracy and reliability, considering the building information they have at hand, which will serve as input for the tool. Yezioro, Dong and Leite[30] developed an artificial intelligence approach towards assessing building performance simulation results and found that more detailed simulation tools have the best simulation performance in terms of heating and cooling electricity consumption within 3% of mean absolute error.

Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) is a rating system organized by the US Green Building Council (USGBC) to promote environmental responsibility in building design. They currently offer four levels of certification for existing buildings (LEED-EBOM) and new construction (LEED-NC) based on a building's compliance with the following criteria: Sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, materials and resources, indoor environmental quality, and innovation in design.[31] In 2013, USGBC developed the LEED Dynamic Plaque, a tool to track building performance against LEED metrics and a potential path to recertification. The following year, the council collaborated with Honeywell to pull data on energy and water use, as well as indoor air quality from a BAS to automatically update the plaque, providing a near-real-time view of performance. The USGBC office in Washington, D.C. is one of the first buildings to feature the live-updating LEED Dynamic Plaque.[32]

A deep energy retrofit is a whole-building analysis and construction process that uses to achieve much larger energy savings than conventional energy retrofits. Deep energy retrofits can be applied to both residential and non-residential (“commercial”) buildings. A deep energy retrofit typically results in energy savings of 30 percent or more, perhaps spread over several years, and may significantly improve the building value.[33] The Empire State Building has undergone a deep energy retrofit process that was completed in 2013. The project team, consisting of representatives from Johnson Controls, Rocky Mountain Institute, Clinton Climate Initiative, and Jones Lang LaSalle will have achieved an annual energy use reduction of 38% and $4.4 million.[34] For example, the 6,500 windows were remanufactured onsite into superwindows which block heat but pass light. Air conditioning operating costs on hot days were reduced and this saved $17 million of the project's capital cost immediately, partly funding other retrofitting.[35] Receiving a gold Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating in September 2011, the Empire State Building is the tallest LEED certified building in the United States.[23] The Indianapolis City-County Building recently underwent a deep energy retrofit process, which has achieved an annual energy reduction of 46% and $750,000 annual energy saving.

Energy retrofits, including deep, and other types undertaken in residential, commercial or industrial locations are generally supported through various forms of financing or incentives. Incentives include pre-packaged rebates where the buyer/user may not even be aware that the item being used has been rebated or "bought down". "Upstream" or "Midstream" buy downs are common for efficient lighting products. Other rebates are more explicit and transparent to the end user through the use of formal applications. In addition to rebates, which may be offered through government or utility programs, governments sometimes offer tax incentives for energy efficiency projects. Some entities offer rebate and payment guidance and facilitation services that enable energy end use customers tap into rebate and incentive programs.

To evaluate the economic soundness of energy efficiency investments in buildings, cost-effectiveness analysis or CEA can be used. A CEA calculation will produce the value of energy saved, sometimes called negawatts, in $/kWh. The energy in such a calculation is virtual in the sense that it was never consumed but rather saved due to some energy efficiency investment being made. Thus CEA allows comparing the price of negawatts with price of energy such as electricity from the grid or the cheapest renewable alternative. The benefit of the CEA approach in energy systems is that it avoids the need to guess future energy prices for the purposes of the calculation, thus removing the major source of uncertainty in the appraisal of energy efficiency investments.[36]

Energy efficiency by country

Europe

Energy efficiency targets for 2020 and 2030.

The first EU-wide energy efficiency target was set in 1998. Member states agreed to improve energy efficiency by 1 percent a year over twelve years. In addition, legislation about products, industry, transport and buildings has contributed to a general energy efficiency framework. More effort is needed to address heating and cooling: there is more heat wasted during electricity production in Europe than is required to heat all buildings in the continent.[37] All in all, EU energy efficiency legislation is estimated to deliver savings worth the equivalent of up to 326 million tons of oil per year by 2020.[38]

The EU set itself a 20% energy savings target by 2020 compared to 1990 levels, but member states decide individually how energy savings will be achieved. At an EU summit in October 2014, EU countries agreed on a new energy efficiency target of 27% or greater by 2030. One mechanism used to achieve the target of 27% is the 'Suppliers Obligations & White Certificates'.[39] The ongoing debate around the 2016 Clean Energy Package also puts an emphasis on energy efficiency, but the goal will probably remain around 30% greater efficiency compared to 1990 levels.[38] Some have argued that this will not be enough for the EU to meet its Paris Agreement goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40% compared to 1990 levels.

Australia

The Australian national government is actively leading the country in efforts to increase their energy efficiency, mainly through the government's Department of Industry and Science. In July 2009, the Council of Australian Governments, which represents the individual states and territories of Australia, agreed to a National Strategy on Energy Efficiency (NSEE).[40]

This is a ten-year plan accelerating the implementation of a nationwide adoption of energy-efficient practices and a preparation for the country's transformation into a low carbon future. There are several different areas of energy use addressed within the NSEE. But, the chapter devoted to the approach on energy efficiency that is to be adopted on a national level stresses four points in achieving stated levels of energy efficiency. They are:

- To help households and businesses transition to a low carbon future

- To streamline the adoption of efficient energy

- To make buildings more energy-efficient

- For governments to work in partnership and lead the way to energy efficiency

The overriding agreement that governs this strategy is the National Partnership Agreement on Energy Efficiency.[41]

This document also explains the role of both the commonwealth and the individual states and territories in the NSEE, as well provides for the creation of benchmarks and measurement devices which will transparently show the nation's progress in relation to the stated goals, and addresses the need for funding of the strategy in order to enable it to move forward.

Canada

In August 2017, the Government of Canada released Build Smart - Canada's Buildings Strategy, as a key driver of the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, Canada's national climate strategy.

The Build Smart strategy seeks to dramatically increase the energy-efficiency performance of existing and new Canadian buildings, and establishes five goals to that end:

- Federal, provincial, and territorial governments will work to develop and adopt increasingly stringent model building codes, starting in 2020, with the goal that provinces and territories adopt a “net-zero energy ready” model building code by 2030.

- Federal, provincial, and territorial governments will work to develop a model code for existing buildings by 2022, with the goal that provinces and territories adopt the code.

- Federal, provincial, and territorial governments will work together with the aim of requiring labelling of building energy use by as early as 2019.

- The federal government will set new standards for heating equipment and other key technologies to the highest level of efficiency that is economically and technically achievable.

- Provincial and territorial governments will work to sustain and expand efforts to retrofit existing buildings by supporting energy efficiency improvements and by accelerating the adoption of high-efficiency equipment while tailoring their programs to regional circumstances.

The strategy details a range of activities the Government of Canada will pursue, and investments it will make, in support of the goals. As of early 2018, only one of Canada's 10 provinces and three territories, British Columbia, has developed a policy in support of federal government's goal to reach net zero energy ready ambitions: the BC Energy Step Code.

Local British Columbia governments may use the BC Energy Step Code, if they wish, to incentivize or require a level of energy efficiency in new construction that goes above and beyond the requirements of the base building code. The regulation and standard is designed as a technical roadmap to help the province reach its target that all new buildings will attain a net zero energy ready level of performance by 2032.

Germany

Energy efficiency is central to energy policy in Germany.[42] As of late 2015, national policy includes the following efficiency and consumption targets (with actual values for 2014):[43]:4

| Efficiency and consumption target | 2014 | 2020 | 2050 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary energy consumption (base year 2008) | −8.7% | −20% | −50% |

| Final energy productivity (2008–2050) | 1.6%/year (2008–2014) | 2.1%/year (2008–2050) | |

| Gross electricity consumption (base year 2008) | −4.6% | −10% | −25% |

| Primary energy consumption in buildings (base year 2008) | −14.8% | −80% | |

| Heat consumption in buildings (base year 2008) | −12.4% | −20% | |

| Final energy consumption in transport (base year 2005) | 1.7% | −10% | −40% |

Recent progress toward improved efficiency has been steady aside from the financial crisis of 2007–08.[44] Some however believe energy efficiency is still under-recognised in terms of its contribution to Germany's energy transformation (or Energiewende).[45]

Efforts to reduce final energy consumption in transport sector have not been successful, with a growth of 1.7% between 2005–2014. This growth is due to both road passenger and road freight transport. Both sectors increased their overall distance travelled to record the highest figures ever for Germany. Rebound effects played a significant role, both between improved vehicle efficiency and the distance travelled, and between improved vehicle efficiency and an increase in vehicle weights and engine power.[46]:12

On 3 December 2014, the German federal government released its National Action Plan on Energy Efficiency (NAPE).[47][48] The areas covered are the energy efficiency of buildings, energy conservation for companies, consumer energy efficiency, and transport energy efficiency. The policy contains both immediate and forward-looking measures. The central short-term measures of NAPE include the introduction of competitive tendering for energy efficiency, the raising of funding for building renovation, the introduction of tax incentives for efficiency measures in the building sector, and the setting up energy efficiency networks together with business and industry. German industry is expected to make a sizeable contribution.

On 12 August 2016, the German government released a green paper on energy efficiency for public consultation (in German).[49][50] It outlines the potential challenges and actions needed to reduce energy consumption in Germany over the coming decades. At the document's launch, economics and energy minister Sigmar Gabriel said "we do not need to produce, store, transmit and pay for the energy that we save".[49] The green paper prioritizes the efficient use of energy as the "first" response and also outlines opportunities for sector coupling, including using renewable power for heating and transport.[49] Other proposals include a flexible energy tax which rises as petrol prices fall, thereby incentivizing fuel conservation despite low oil prices.[51]

Poland

In May 2016 Poland adopted a new Act on Energy Efficiency, to enter into force on 1 October 2016.[52]

United States

A 2011 Energy Modeling Forum study covering the United States examines how energy efficiency opportunities will shape future fuel and electricity demand over the next several decades. The US economy is already set to lower its energy and carbon intensity, but explicit policies will be necessary to meet climate goals. These policies include: a carbon tax, mandated standards for more efficient appliances, buildings and vehicles, and subsidies or reductions in the upfront costs of new more energy-efficient equipment.[53]

Industry

Industries use a large amount of energy to power a diverse range of manufacturing and resource extraction processes. Many industrial processes require large amounts of heat and mechanical power, most of which is delivered as natural gas, petroleum fuels, and electricity. In addition some industries generate fuel from waste products that can be used to provide additional energy.

Because industrial processes are so diverse it is impossible to describe the multitude of possible opportunities for energy efficiency in industry. Many depend on the specific technologies and processes in use at each industrial facility. There are, however, a number of processes and energy services that are widely used in many industries.

Various industries generate steam and electricity for subsequent use within their facilities. When electricity is generated, the heat that is produced as a by-product can be captured and used for process steam, heating or other industrial purposes. Conventional electricity generation is about 30% efficient, whereas combined heat and power (also called co-generation) converts up to 90 percent of the fuel into usable energy.[54]

Advanced boilers and furnaces can operate at higher temperatures while burning less fuel. These technologies are more efficient and produce fewer pollutants.[54]

Over 45 percent of the fuel used by US manufacturers is burnt to make steam. The typical industrial facility can reduce this energy usage 20 percent (according to the US Department of Energy) by insulating steam and condensate return lines, stopping steam leakage, and maintaining steam traps.[54]

Electric motors usually run at a constant speed, but a variable speed drive allows the motor's energy output to match the required load. This achieves energy savings ranging from 3 to 60 percent, depending on how the motor is used. Motor coils made of superconducting materials can also reduce energy losses.[54] Motors may also benefit from voltage optimisation. [55][56]

Industry uses a large number of pumps and compressors of all shapes and sizes and in a wide variety of applications. The efficiency of pumps and compressors depends on many factors but often improvements can be made by implementing better process control and better maintenance practices. Compressors are commonly used to provide compressed air which is used for sand blasting, painting, and other power tools. According to the US Department of Energy, optimizing compressed air systems by installing variable speed drives, along with preventive maintenance to detect and fix air leaks, can improve energy efficiency 20 to 50 percent.[54]

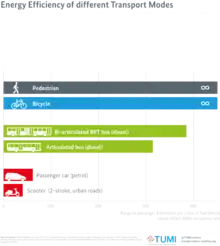

Transportation

Automobiles

The estimated energy efficiency for an automobile is 280 Passenger-Mile/106 Btu.[57] There are several ways to enhance a vehicle's energy efficiency. Using improved aerodynamics to minimize drag can increase vehicle fuel efficiency. Reducing vehicle weight can also improve fuel economy, which is why composite materials are widely used in car bodies.

More advanced tires, with decreased tire to road friction and rolling resistance, can save gasoline. Fuel economy can be improved by up to 3.3% by keeping tires inflated to the correct pressure.[58] Replacing a clogged air filter can improve a cars fuel consumption by as much as 10 percent on older vehicles.[59] On newer vehicles (1980s and up) with fuel-injected, computer-controlled engines, a clogged air filter has no effect on mpg but replacing it may improve acceleration by 6-11 percent.[60] Aerodynamics also aid in efficiency of a vehicle. The design of a car impacts the amount of gas needed to move it through air. Aerodynamics involves the air around the car, which can affect the efficiency of the energy expended.[61]

Turbochargers can increase fuel efficiency by allowing a smaller displacement engine. The 'Engine of the year 2011' is the Fiat TwinAir engine equipped with an MHI turbocharger. "Compared with a 1.2-liter 8v engine, the new 85 HP turbo has 23% more power and a 30% better performance index. The performance of the two-cylinder is not only equivalent to a 1.4-liter 16v engine, but fuel consumption is 30% lower."[62]

Energy-efficient vehicles may reach twice the fuel efficiency of the average automobile. Cutting-edge designs, such as the diesel Mercedes-Benz Bionic concept vehicle have achieved a fuel efficiency as high as 84 miles per US gallon (2.8 L/100 km; 101 mpg‑imp), four times the current conventional automotive average.[63]

The mainstream trend in automotive efficiency is the rise of electric vehicles (all-electric or hybrid electric). Electric engines have more than double the efficiency of internal combustion engines. Hybrids, like the Toyota Prius, use regenerative braking to recapture energy that would dissipate in normal cars; the effect is especially pronounced in city driving.[64] Plug-in hybrids also have increased battery capacity, which makes it possible to drive for limited distances without burning any gasoline; in this case, energy efficiency is dictated by whatever process (such as coal-burning, hydroelectric, or renewable source) created the power. Plug-ins can typically drive for around 40 miles (64 km) purely on electricity without recharging; if the battery runs low, a gas engine kicks in allowing for extended range. Finally, all-electric cars are also growing in popularity; the Tesla Model S sedan is the only high-performance all-electric car currently on the market.

Street lighting

Cities around the globe light up millions of streets with 300 million lights.[65] Some cities are seeking to reduce street light power consumption by dimming lights during off-peak hours or switching to LED lamps.[66] LED lamps are known to reduce the energy consumption by 50% to 80%.[67][68]

Aircraft

There are several ways to reduce energy usage in air transportation, from modifications to the planes themselves, to how air traffic is managed. As in cars, turbochargers are an effective way to reduce energy consumption; however, instead of allowing for the use of a smaller-displacement engine, turbochargers in jet turbines operate by compressing the thinner air at higher altitudes. This allows the engine to operate as if it were at sea-level pressures while taking advantage of the reduced drag on the aircraft at higher altitudes.

Air traffic management systems are another way to increase the efficiency of not just the aircraft but the airline industry as a whole. New technology allows for superior automation of takeoff, landing, and collision avoidance, as well as within airports, from simple things like HVAC and lighting to more complex tasks such as security and scanning.

Alternative fuels

Alternative fuels, known as non-conventional or advanced fuels, are any materials or substances that can be used as fuels, other than conventional fuels. Some well known alternative fuels include biodiesel, bioalcohol (methanol, ethanol, butanol), chemically stored electricity (batteries and fuel cells), hydrogen, non-fossil methane, non-fossil natural gas, vegetable oil, and other biomass sources. The production efficiency of these fuels greatly differs.

Energy conservation

Energy conservation is broader than energy efficiency in including active efforts to decrease energy consumption, for example through behaviour change, in addition to using energy more efficiently. Examples of conservation without efficiency improvements are heating a room less in winter, using the car less, air-drying your clothes instead of using the dryer, or enabling energy saving modes on a computer. As with other definitions, the boundary between efficient energy use and energy conservation can be fuzzy, but both are important in environmental and economic terms.[69] This is especially the case when actions are directed at the saving of fossil fuels.[70] Energy conservation is a challenge requiring policy programmes, technological development and behavior change to go hand in hand. Many energy intermediary organisations, for example governmental or non-governmental organisations on local, regional, or national level, are working on often publicly funded programmes or projects to meet this challenge.[71] Psychologists have also engaged with the issue of energy conservation and have provided guidelines for realizing behavior change to reduce energy consumption while taking technological and policy considerations into account.[72]

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory maintains a comprehensive list of apps useful for energy efficiency.[73]

Commercial property managers that plan and manage energy efficiency projects generally use a software platform to perform energy audits and to collaborate with contractors to understand their full range of options. The Department of Energy (DOE) Software Directory describes EnergyActio software, a cloud based platform designed for this purpose.

Sustainable energy

Energy efficiency and renewable energy are considered as main elements in sustainable energy policy. Both strategies must be developed concurrently in order to stabilize and reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Efficient energy use is essential to slowing the energy demand growth so that rising clean energy supplies can make deep cuts in fossil fuel use. If energy use grows too rapidly, renewable energy development will chase a receding target. Likewise, unless clean energy supplies come online rapidly, slowing demand growth will only begin to reduce total carbon emissions; a reduction in the carbon content of energy sources is also needed. A sustainable energy economy thus requires major commitments to both efficiency and renewables.[74]

Rebound effect

If the demand for energy services remains constant, improving energy efficiency will reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions. However, many efficiency improvements do not reduce energy consumption by the amount predicted by simple engineering models. This is because they make energy services cheaper, and so consumption of those services increases. For example, since fuel efficient vehicles make travel cheaper, consumers may choose to drive farther, thereby offsetting some of the potential energy savings. Similarly, an extensive historical analysis of technological efficiency improvements has conclusively shown that energy efficiency improvements were almost always outpaced by economic growth, resulting in a net increase in resource use and associated pollution.[75] These are examples of the direct rebound effect.[76]

Estimates of the size of the rebound effect range from roughly 5% to 40%.[77][78][79] The rebound effect is likely to be less than 30% at the household level and may be closer to 10% for transport.[76] A rebound effect of 30% implies that improvements in energy efficiency should achieve 70% of the reduction in energy consumption projected using engineering models. Saunders et al. showed in 2010 that lighting has accounted for about 0.7% of GDP across many societies and hundreds of years, implying a rebound effect of 100%.[80] However, some of the authors argue in a followup paper that increased lighting generally increases economic welfare and has substantial benefits.[81] A 2014 study has shown the rebound effect to be rather low for household lighting, in particular for high use bulbs.[82]

Organisations and programs

International

- 80 Plus

- 2000-watt society

- IEA Solar Heating & Cooling Implementing Agreement Task 13

- International Institute for Energy Conservation

- International Energy Agency (e.g. One Watt initiative)

- International Electrotechnical Commission

- International Partnership for Energy Efficiency Cooperation

- World Sustainable Energy Days

China

- National Development and Reform Commission

- National Energy Conservation Center

- Energy Research Institute

Australia

- Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency

- Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts

- Sustainable House Day

European Union

- Building energy rating

- Eco-Design of Energy-Using Products Directive

- Energy efficiency in Europe (study)

- Orgalime, the European engineering industries association

Finland

Iceland

India

Indonesia

Japan

Lebanon

United Kingdom

- The Carbon Trust

- Energy Saving Trust

- National Energy Action

- National Energy Foundation

- Creative Energy Homes

- Energy Managers Association

United States

- Alliance to Save Energy

- American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy

- Building Codes Assistance Project

- Building Energy Codes Program

- Consortium for Energy Efficiency

- Energy Star, from United States Environmental Protection Agency

- Industrial Assessment Center

- National Electrical Manufacturers Association

- Rocky Mountain Institute

See also

- Cogeneration

- Carbon offset

- Data center infrastructure efficiency

- Distributed generation

- Electrical energy efficiency on United States farms

- Electric vehicle § Efficiency

- Energy audit

- Energy conservation measures

- Energy conversion efficiency

- Energy efficiency implementation

- Energy recovery

- Energy resilience

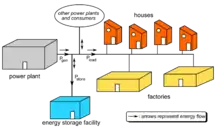

- Energy storage

- Energy storage as a service (ESaaS)

- EU Energy Efficiency Directive 2012/27/EU

- European Union energy label

- Khazzoom–Brookes postulate

- Performance per watt

- Lee Schipper

- List of energy storage projects

- List of least carbon efficient power stations

- Negawatt power

- Passenger miles per gallon

- Peak oil

- Renewable energy

- Renewable heat

- Standby power

- US Department of Energy Solar Decathlon

- The Green Deal

- World Energy Engineering Congress

- Energy Reduction Assets

- John A. "Skip" Laitner

- Passive house

- Light pollution

References

- Diesendorf, Mark (2007). Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy, UNSW Press, p. 86.

- Sophie Hebden (2006-06-22). "Invest in clean technology says IEA report". Scidev.net. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- Indra Overland (2010). "Subsidies for Fossil Fuels and Climate Change: A Comparative Perspective". International Journal of Environmental Studies. 67: 203–217.

- Prindle, Bill; Eldridge, Maggie; Eckhardt, Mike; Frederick, Alyssa (May 2007). The twin pillars of sustainable energy: synergies between energy efficiency and renewable energy technology and policy. Washington, DC, USA: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.545.4606.

- Zehner, Ozzie (2012). Green Illusions. London: UNP. pp. 180–181.

- "Loading Order White Paper" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- Kennan, Hallie. "Working Paper: State Green Banks for Clean Energy" (PDF). Energyinnovation.org. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Weatherization in Austin, Texas". Green Collar Operations. Archived from the original on 2009-08-03. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- Steve Lohr (November 29, 2006). "Energy Use Can Be Cut by Efficiency, Survey Says..." The New York Times. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- "Press Release: Vienna UN conference shows consensus on key building blocks for effective international response to climate change" (PDF). Unfccc.int. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ISO 17743:2016 - Energy savings — Definition of a methodological framework applicable to calculation and reporting on energy savings. International Standards Association (ISO). Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved 2016-11-11.

- ISO 17742:2015 — Energy efficiency and savings calculation for countries, regions and cities. International Standards Association (ISO). Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved 2016-11-11.

- "Energy Efficiency Indicators 2020". International Energy Agency. June 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- International Energy Agency: Report on Multiple Benefits of Energy Efficiency. OECD, Paris, 2014.

- Weinsziehr, T.; Skumatz, L. Evidence for Multiple Benefits or NEBs: Review on Progress and Gaps from the IEA Data and Measurement Subcommittee. In Proceedings of the International Energy Policy & Programme Evaluation Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 7–9 June 2016.

- Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Novikova, A.; Sharmina, M. Counting good: Quantifying the co-benefits of improved efficiency in buildings. In Proceedings of the ECEEE 2009 Summer Study, Stockholm, Sweden, 1–6 June 2009.

- B Baatz, J Barrett, B Stickles: Estimating the Value of Energy Efficiency to Reduce Wholesale Energy Price Volatility. ACEEE, Washington D.C., 2018.

- Tuominen, P., Seppänen, T. (2017): Estimating the Value of Price Risk Reduction in Energy Efficiency Investments in Buildings. Energies. Vol. 10, p. 1545.

- "Ecosavings". Electrolux.com. Archived from the original on 2011-08-06. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- "Ecosavings (Tm) Calculator". Electrolux.com. Archived from the original on 2010-08-18. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- "Pathways to a Low-Carbon Economy: Version 2 of the Global Greenhouse Gas Abatement Cost Curve". McKinsey Global Institute: 7. 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- Environmental and Energy Study Institute. "Energy-Efficient Buildings: Using whole building design to reduce energy consumption in homes and offices". Eesi.org. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- "Empire State Building Achieves LEED Gold Certification | Inhabitat New York City". Inhabitat.com. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- Alison Gregor. "Declared the tallest building in the US — One World Trade Center is on track for LEED". United States Green Building Council. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- "ENERGY STAR Buildings and Plants". Energystar.gov. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Juha Forsström, Pekka Lahti, Esa Pursiheimo, Miika Rämä, Jari Shemeikka, Kari Sipilä, Pekka Tuominen & Irmeli Wahlgren (2011): Measuring energy efficiency. VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland.

- Most heat is lost through the walls of your building, in fact about a third of all heat losses occur in this area. Simply Business Energy Archived 2016-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Creating Energy Efficient Offices - Electrical Contractor Fit-out Article

- Matar, W (2015). "Beyond the end-consumer: how would improvements in residential energy efficiency affect the power sector in Saudi Arabia?". Energy Efficiency. 9 (3): 771–790. doi:10.1007/s12053-015-9392-9.

- Yezioro, A; Dong, B; Leite, F (2008). "An applied artificial intelligence approach towards assessing building performance simulation tools". Energy and Buildings. 40 (4): 612. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2007.04.014.

- "LEED v4 for Building Design and Construction Checklist". USGBC. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- "Honeywell, USGBC Tool Monitors Building Sustainability". Environmental Leader. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-06-11. Retrieved 2013-08-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Visit > Sustainability & Energy Efficiency | Empire State Building". Esbnyc.com. 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- Amory Lovins (March–April 2012). "A Farewell to Fossil Fuels". Foreign Affairs.

- Tuominen, Pekka; Reda, Francesco; Dawoud, Waled; Elboshy, Bahaa; Elshafei, Ghada; Negm, Abdelazim (2015). "Economic Appraisal of Energy Efficiency in Buildings Using Cost-effectiveness Assessment". Procedia Economics and Finance. 21: 422–430. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00195-1.

- "Heat Roadmap Europe". Heatroadmap.eu. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- "Energy Atlas 2018: Figures and Facts about Renewables in Europe | Heinrich Böll Foundation". Heinrich Böll Foundation. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- "Suppliers Obligations & White Certificates". Europa.EU. Europa.eu. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

- National Strategy on Energy Efficiency, Industry.gov.au, 16 August 2015, archived from the original on 13 September 2015

- National Partnership Agreement on Energy Efficiency (PDF), Fif.gov.au, 16 August 2015, archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-03-12

- Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (BMWi); Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) (28 September 2010). Energy concept for an environmentally sound, reliable and affordable energy supply (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (BMWi). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- The Energy of the Future: Fourth "Energy Transition" Monitoring Report — Summary (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). November 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-20. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- Schlomann, Barbara; Eichhammer, Wolfgang (2012). Energy efficiency policies and measures in Germany (PDF). Karlsruhe, Germany: Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research ISI. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- Agora Energiewende (2014). Benefits of energy efficiency on the German power sector: summary of key findings from a study conducted by Prognos AG and IAEW (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Agora Energiewende. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

- Löschel, Andreas; Erdmann, Georg; Staiß, Frithjof; Ziesing, Hans-Joachim (November 2015). Statement on the Fourth Monitoring Report of the Federal Government for 2014 (PDF). Germany: Expert Commission on the "Energy of the Future" Monitoring Process. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-05. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- "National Action Plan on Energy Efficiency (NAPE): making more out of energy". Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- Making more out of energy: National Action Plan on Energy Efficiency (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). December 2014. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- "Gabriel: Efficiency First — discuss the Green Paper on Energy Efficiency with us!" (Press release). Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). 12 August 2016. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 2016-09-06.

- Grünbuch Energieeffizienz: Diskussionspapier des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Energie [Green paper on energy efficiency: discussion document by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy] (PDF) (in German). Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). Retrieved 2016-09-06.

- Amelang, Sören (15 August 2016). "Lagging efficiency to get top priority in Germany's Energiewende". Clean Energy Wire (CLEW). Berlin, Germany. Retrieved 2016-09-06.

- Sekuła-Baranska, Sandra (24 May 2016). "New Act on Energy Efficiency passed in Poland". Noerr. Munich, Germany. Retrieved 2016-09-20.

- Huntington, Hillard (2011). EMF 25: Energy efficiency and climate change mitigation — Executive summary report (volume 1) (PDF). Stanford, CA, USA: Energy Modeling Forum. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- Environmental and Energy Study Institute. "Industrial Energy Efficiency: Using new technologies to reduce energy use in industry and manufacturing" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- "Voltage Optimization Explained | Expert Electrical". www.expertelectrical.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- "How To Save Money With Voltage Optimization". CAS Dataloggers. 2019-01-29. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- Richard C. Dorf, The Energy Factbook, McGraw-Hill, 1981

- "Tips to improve your Gas Mileage". Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- "Automotive Efficiency : Using technology to reduce energy use in passenger vehicles and light trucks" (PDF). Eesi.org. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Effect of Intake Air Filter Condition on Vehicle Fuel Economy" (PDF). Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "What Makes a Fuel Efficient Car? The 8 Most Fuel Efficient Cars". CarsDirect. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- "Fiat 875cc TwinAir named International Engine of the Year 2011". Green Car Congress.

- Nom * (2013-06-28). "La Prius de Toyota, une référence des voitures hybrides | L'énergie en questions". Lenergieenquestions.fr. Archived from the original on 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ltd, Research and Markets. "Global LED and Smart Street Lighting: Market Forecast (2017 - 2027)". Researchandmarkets.com. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Edmonton, City of (26 March 2019). "Street Lighting". Edmonton.ca. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Guide for energy efficient street lighting installations" (PDF). Intelligent Energy Europe. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Sudarmono, Panggih; Deendarlianto; Widyaparaga, Adhika (2018). "Energy efficiency effect on the public street lighting by using LED light replacement and kwh-meter installation at DKI Jakarta Province, Indonesia". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 1022: 012021. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1022/1/012021.

- Dietz, T. et al. (2009).Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce US carbon emissions. PNAS. 106(44).

- Diesendorf, Mark (2007). Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy, UNSW Press, p. 87.

- Breukers, Heiskanen, et al. (2009). Interaction schemes for successful demand-side management. Deliverable 5 of the Changing Behaviour Archived 2010-11-30 at the Wayback Machine project. Funded by the EC (#213217).

- Kok, G., Lo, S.H., Peters, G.J. & R.A.C. Ruiter (2011), Changing Energy-Related Behavior: An Intervention Mapping Approach, Energy Policy, 39:9, 5280-5286, doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2011.05.036

- "National Renewable Energy Laboratory. (2012)". En.openei.org. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-11. Retrieved 2014-12-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)(American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy)

- Huesemann, Michael H., and Joyce A. Huesemann (2011). Technofix: Why Technology Won't Save Us or the Environment, Chapter 5, "In Search of Solutions II: Efficiency Improvements", New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, Canada.

- The Rebound Effect: an assessment of the evidence for economy-wide energy savings from improved energy efficiency Archived 2008-09-10 at the Wayback Machine pp. v-vi.

- Greening, Lorna A.; David L. Greene; Carmen Difiglio (2000). "Energy efficiency and consumption—the rebound effect—a survey". Energy Policy. 28 (6–7): 389–401. doi:10.1016/S0301-4215(00)00021-5.

- Kenneth A. Small and Kurt Van Dender (September 21, 2005). "The Effect of Improved Fuel Economy on Vehicle Miles Traveled: Estimating the Rebound Effect Using US State Data, 1966-2001". University of California Energy Institute: Policy & Economics. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- "Energy Efficiency and the Rebound Effect: Does Increasing Efficiency Decrease Demand?" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-10-01.

- Tsao, J Y; Saunders, H D; Creighton, J R; Coltrin, M E; Simmons, J A (8 September 2010). "Solid-state lighting: an energy-economics perspective". Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 43 (35): 354001. Bibcode:2010JPhD...43I4001T. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/43/35/354001.

- Tsao, J Y; Saunders, H D (October 2012). "Rebound effects for lighting". Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 49: 477–478. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.06.050.

- Schleich, J; Mills, B; Dütschke, E. (2014). "A Brighter Future? Quantifying the Rebound Effect in Energy Efficient Lighting" (PDF). Energy Policy. 72: 35–42. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2014.04.028.