Collaboration in German-occupied Poland

Throughout World War II, Poland was a member of the Allied coalition that fought Nazi Germany. During the German occupation of Poland, some citizens of all its major ethnic groups collaborated with the Germans. Estimates of the number of collaborators vary. Collaboration in Poland was less institutionalized than in some other countries[1] and has been described as marginal.[2][3] During and after the war, the Polish government in exile and the Polish resistance movement punished collaborators and sentenced to death thousands of them.

Background

Following the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Hitler sought to establish Poland as a client state, proposing a multilateral territorial exchange and an extension of the German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact. The Polish government, fearing subjugation to Nazi Germany, instead chose to form an alliance with Britain (and later with France). In response, Germany withdrew from the non-aggression pact and, shortly before invading Poland, signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Soviet Union, safeguarding Germany against Soviet retaliation if it invaded Poland, and prospectively dividing Poland between the two totalitarian powers.

On 1 September 1939 Germany invaded Poland. The German army overran Polish defenses while inflicting heavy civilian losses, and by 13 September had conquered most of western Poland. On 17 September the Soviet Union invaded the country from the east, conquering most of eastern Poland, along with the Baltic states and parts of Finland in 1940. Some 140,000 Polish soldiers and airmen escaped to Romania and Hungary, and later many soon joining the Polish Armed Forces in France. Poland's government crossed over into Romania, later forming a government-in-exile in France and then in London, following the French capitulation. Poland as a polity never surrendered to the Germans.[4]

Nazi authorities annexed the westernmost parts of Poland and the former Free City of Danzig, incorporating it directly to Nazi Germany, and placed the remaining German-occupied territory under the administration of the newly formed General Government. The Soviet Union annexed the rest of Poland, incorporating its territories into the Belarusian and Ukrainian Soviet republics.[5] Germany's primary aim in Eastern Europe was the expansion of the German Lebensraum which necessitated according to Nazi views the elimination or deportation of all non-Germanic ethnicities, including Poles; the areas controlled by the General Government were to become "free" of Poles within 15–20 years.[6] This resulted in harsh policies which targeted the Polish population, in addition to the explicit goal of exterminating Polish Jews, which was carried out by Nazi Germany in the occupied Polish territories.

Individual collaboration

Estimates of the number of individual Polish collaborators vary according to the definition of "collaboration".[7] According to Klaus-Peter Friedrich estimates range from as few as 7,000 to as many as several hundred thousand (including Polish officials employed by the German authorities; Blue Police officers, who were required to serve; compulsory "labor service" workers; members of Poland's German minority; and even Poland's peasantry, which on the one hand was subject to food requisitions by the Germans, and on the other collaborated and benefited financially from the wartime economy and the removal of Jews from the Polish economy for much of the war.[3][8] Post-war communist Polish propaganda painted the entire non-communist Polish resistance, in particular the Home Army, as "Nazi collaborators".[9]

Czesław Madajczyk estimates that 5% of the population in the General Government actively collaborated, which he contrasts with the 25% who actively resisted the occupation.[10] Historian John Connelly writes that "only a relatively small percentage of the Polish population engaged in activities that may be described as collaboration, when seen against the backdrop of European and world history." However, he criticizes the same population for its indifference to the Jewish plight, a phenomenon he terms "structural collaboration" (see more below).[7]

Political collaboration

Unlike the situation in most German-occupied European countries where the Germans successfully installed collaborationist governments, in occupied Poland there was no puppet government.[3][11][12][13] The Germans had initially considered the creation of a collaborationist Polish cabinet to administer, as a protectorate, the occupied Polish territories that had not been annexed outright into the Third Reich.[13][14][15] At the beginning of the war German officials contacted several Polish leaders with proposals for collaboration, but they all refused.[16][17] Among those who rejected the German offers were Wincenty Witos, peasant party leader and former Prime Minister;[18][13][19] Prince Janusz Radziwiłł; and Stanisław Estreicher, prominent scholar from the Jagiellonian University.[20][21][22][12]

In 1940, during the German invasion of France, the French government suggested that Polish politicians in France negotiate an accommodation with Germany; and in Paris the prominent journalist Stanislaw Mackiewicz tried to get Polish President Wladyslaw Raczkiewicz to negotiate with the Germans, as the French defenses were collapsing and German victory seemed inevitable. Three days later the Polish Government and Polish National Council rejected discussing capitulation and declared they would fight on until full victory over Nazi Germany. A group of eight low-ranking Polish politicians and officers broke with the Polish Government and in Lisbon, Portugal, addressed a memorandum to Germany, asking for discussions about restoring a Polish state under German occupation, which was rejected by the Germans. According to Czeslaw Madajczyk, in view of the low profile of the Poles involved and of Berlin's rejection of the memorandum, no political collaboration can be said to have taken place.[23]

The Nazi racial policies and Germany's plans for the conquered Polish territories, on one hand, and Polish anti-German attitudes on the other, combined to prevent any Polish-German political collaboration.[16] The Nazis envisioned the eventual disappearance of the Polish nation, which was to be replaced by German settlers.[3][13][24] In April 1940 Hitler banned any negotiations concerning any degree of autonomy for the Poles, and no further consideration was given to the idea.[13]

Shortly after the German occupation began, pro-German right-wing politician Andrzej Świetlicki formed an organization - the National Revolutionary Camp - and approached the Germans with various offers of collaboration, which they ignored. Świetlicki was arrested and executed in 1940.[25] Władysław Studnicki, another nationalist maverick politician and anti-communist publicist,[26] and Leon Kozłowski, a former Prime Minister, each favored Polish-German cooperation against the Soviet Union, but they too were rejected by the Germans.[25]

Security forces

The main security forces in German-occupied Poland were some 550,000 soldiers and 80,000 SS and police officials sent from Germany.[27]

Blue Police

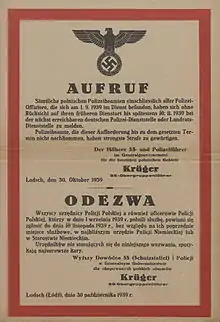

In October 1939 the German authorities ordered mobilization of the prewar Polish police to serve under the German Ordnungspolizei, thus creating the auxiliary "Blue Police" that supplemented the principal German forces. The Polish policemen were to report for duty by 10 November 1939[28] or face death.[29] At its peak in May 1944, the Blue Police numbered some 17,000 men.[30] Their primary task was to act as a regular police force dealing with criminal activities, but the Germans also used them in combating smuggling and resistance, rounding up random civilians (łapanka) for forced labor or for execution in reprisal for Polish resistance activities (e.g., the Polish underground's execution of Polish traitors or egregiously brutal Germans), patrolling for Jewish ghetto escapees, and in support of military operations against the Polish resistance.[3][31]

Polish Criminal Police (Polnische Kriminalpolizei)

The Germans also created a Polnische Kriminalpolizei.. The Polish criminal police team was trained at the Security Police School and the Security Service of the Reichsführer SS (SD) in Rabka-Zdrój. It's estimated that there were between 1,790 and 2,800 ethnic Poles in the Polish Kripo units.[32] The organization of the Polish Criminal Police was analogous to the organization of the German “Kriminalpolizei" and consisted of various police stations. Station 1 dealt with robberies, assaults, murders and sabotage; station 2 - with small thefts; station 3 - with burglary and house thieves; station 4 - moral crimes; station 5 - with internal service, search of Jews in hiding and other wanted persons; station 6 - with registration of wanted persons, station 7 - with forensic technique, and photographic laboratory.[33]

Auxiliary police

The German General Government tried to form additional Polish auxiliary police units—Schutzmannschaft Battalion 202 in 1942, and Schutzmannschaft Battalion 107 in 1943. Very few men volunteered, and the Germans decided on forced conscription to fill their ranks. Most of the conscripts subsequently deserted, and the two units were disbanded.[34] Schutzmannschaft Battalion 107 mutinied against its German officers, disarmed them, and joined the Home Army resistance.[35]

Some Poles also passed on the side of the Soviet partisans - like Mikołaj Kunicki, Kompanieführer in Schutzmannschaft 104. Poles also served in Byelorussian Auxiliary Police [36] or in Ypatingasis būrys [37] - due to the fact that part of Lithuania and Belarus was part of the Second Polish Republic.

In 1944, in the General Government, Germany attempted to recruit 12,000 Polish volunteers to "join the fight against Bolshevism". The campaign failed; only 699 men were recruited, 209 of whom either deserted or were disqualified for health reasons.[38]

Poles in the Wehrmacht

Following the German invasion of Poland in 1939, many former citizens of the Second Polish Republic from across the Polish territories annexed by Nazi Germany were forcibly conscripted into the Wehrmacht in Upper Silesia and in Pomerania. They were declared citizens of the Third Reich by law and therefore subject to drumhead court-martial in case of draft evasion. Professor Ryszard Kaczmarek of the University of Silesia in Katowice, author of a monograph, Polacy w Wehrmachcie (Poles in the Wehrmacht), noted that the scale of this phenomenon was much larger than previously assumed, because 90% of the inhabitants of these two westernmost regions of prewar Poland were ordered to register on the German People's List (Volksliste), regardless of their wishes. The exact number of these conscripts is not known; no data exist beyond 1943.[39]

In June 1946, the British Secretary of State for War reported to Parliament that, of the pre-war Polish citizens who had involuntarily signed the Volksliste and subsequently served in the German Wehrmacht, 68,693 men were captured or surrendered to the Allies in northwest Europe. The overwhelming majority, 53,630 subsequently enlisted in the Polish Army in the West and fought against Germany to the end of World War II.[40][39]

Compulsory civilian service (Baudienst)

In May 1940, the Germans instituted a Baudienst ("construction service") in several districts of the General Government, as a form of compulsory national service that combined hard labor with Nazi indoctrination. Service was rewarded with pocket money, and in some places it was a prerequisite for occupational training. Starting in April 1942, evasion of Baudienst service was punishable by death. By 1944, Baudienst strength had grown to some 45,000 servicemen.[41]

Baudienst servicemen were sometimes deployed in support of aktions (roundup of Jews for deportation or extermination), for example to blockade Jewish quarters or to search Jewish homes for hideaways and valuables. After such operations the servicemen were rewarded with vodka and cigarettes.[3] Disobedience while in "service" was punished with commitment to punitive camps.[42]

There were three Baudienst branches:

- Polnischer Baudienst (Polish Labor Service)

- Ukrainischer Heimatdienst (Ukrainian National Service)

- Goralischer Heimatdienst (Goral National Service)

Cultural collaboration

Film and theater

In occupied Poland there was no Polish film industry.[43] However, a few former Polish citizens collaborated with the Germans in making films such as the 1941 anti-Polish propaganda film Heimkehr (Homecoming). In that film, casting for minor parts played by Polish actors was done by Volksdeutscher actor and Gestapo agent Igo Sym, who during the filming, on 7 March 1941, was shot in his Warsaw apartment by the Polish Union of Armed Struggle resistance movement; after the war, the Polish performers were sentenced for collaboration in an anti-Polish propaganda undertaking, with punishments ranging from official reprimand to imprisonment. Some Polish actors were coerced by the Germans into performing, as in the case of Bogusław Samborski, who played in Heimkehr probably in order to save his Jewish wife.[44]

During the occupation, feature-film showings were preceded by propaganda newsreels of Die Deutsche Wochenschau (The German Weekly Review). Some feature films likewise contained Nazi propaganda. The Polish underground discouraged Poles from attending movies, advising them, in the words of the rhymed couplet, "Tylko świnie siedzą w kinie" ("Only swine go to the movies").[45]

Following the Polish underground's execution of Igo Sym, in reprisal the Germans took hostages and, on 11 March 1941, executed 21 at their Palmiry killing grounds. They also arrested several actors and theater directors and sent them to Auschwitz, including such notable figures as Stefan Jaracz and Leon Schiller.[46]

The largest theater for Polish audiences was Warsaw's Komedia (Comedy). There were also a dozen small theaters. Polish actors were forbidden by the underground to perform in these theaters, but some did and were punished after the war. Many other actors supported themselves by working as waiters. Adolf Dymsza performed in legal cabarets and wasn't allowed to perform at Warsaw during a short period after the war.[47] A theater producer Zygmunt Ipohorski-Lenkiewicz was shot as a Gestapo agent.

Press

The legal press in German-occupied Poland was a German propaganda tool, which Poles called gadzinówka ("reptile press").[38] Many respected journalists refused to work for the Germans; and those writing for the German-controlled press were considered collaborators.

Jan Emil Skiwski, a writer and journalist of extreme National Democrat and fascist orientation, collaborated with Germany, publishing pro-Nazi Polish newspapers in German-occupied Poland. Toward war's end, he escaped advancing Soviet armies, fled Europe, and spent the rest of his life under an assumed name in Venezuela.

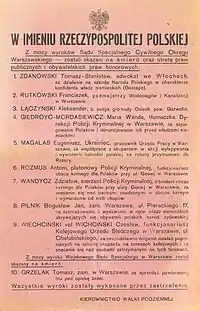

Collaboration and the resistance

The main armed resistance organization in Poland was the Home Army (Armia Krajowa, or AK), numbering some 400,000 members, including Jewish fighters.[48][49][50][51] The Home Army command rejected any talks with the German authorities,[49]:88 but some Home Army units in eastern Poland did maintain contacts with the Germans in order to gain intelligence on German morale and preparedness and perhaps acquire needed weapons.[52] The Germans made several attempts at arming regional Home Army units in order to encourage them to act against Soviet partisans operating in the Nowogródek and Vilnius areas. Local Home Army units accepted arms but used them for their own purposes, disregarding the Germans' intents and even turning the weapons against the Germans.[53][54][49] Tadeusz Piotrowski concludes that "[these deals] were purely tactical, short-term arrangements"[49]:88 and quotes Joseph Rothschild that "the Polish Home Army was by and large untainted by collaboration."[49]:90

The Polish right-wing National Armed Forces (Narodowe Siły Zbrojne, or NSZ) – a nationalist, anti-communist organization,[55]:137[56]:371[57] widely perceived as anti-Semitic[58][59]:147[56]:371[60][61] – did not have a uniform policy regarding Jews.[49]:96-97 Its attitude to them drew on anti-semitism and anti-communism, perceiving Jewish partisans and refugees as "pro-Soviet elements" and members of an ethnicity foreign to the Polish nation. Except in rare cases,[49]:96 the NSZ did not admit Jews,[59]:149 and on several occasions killed or delivered Jewish partisans to the German authorities[59]:149 and murdered Jewish refugees.[58][59]:141[62] NSZ units also frequently skirmished with partisans of the Polish communist People's Army (Armia Ludowa).

At least two NSZ units operated with the acquiescence or cooperation of the Germans at different times.[59]:149 In late 1944, in the face of advancing Soviet forces, the Holy Cross Mountains Brigade, numbering 800-1,500 fighters, decided to cooperate with the Germans.[63][64][65] It ceased hostilities against them, accepted their logistical help, and coordinated its retreat to the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Once there, the unit resumed hostilities against the Germans and on 5 May 1945 liberated the Holýšov concentration camp.[66] Another NSZ unit known to collaborate with the Germans was Hubert Jura's unit, also known as Tom's Organization, which operated in the Radom district.[67]

The Communist underground (PPR, GL) denounced Home Army operatives to the Nazis, resulting in 200 arrests. The Germans found a Communist printing shop as a result of one such denunciation by Marian Spychalski.[68][69]

The Holocaust

Historian Martin Winstone writes that only a minority of Poles took part either in persecuting or in helping Jews. He compares Poland with other occupied countries and asserts the largest part of society was indifferent. Regarding the purported low Polish resolve to save Jews, Winstone writes that this tendency may be partly explained by fear of execution by the Germans. He nevertheless notes that the Germans imposed death sentences for many other acts and quotes Michał Berg: "[Poles] were threatened with death not only for sheltering Jews, but for many other things... [but] they kept right on doing them. Why was it that only helping Jews scared them?" Winstone comments, "it may well be that the risk of hiding a Jew was greater, but that is in itself suggestive since the Germans were not the only danger"; he goes on to explain that Poles who had helped Jews were afraid of repercussions even after liberation.[70]

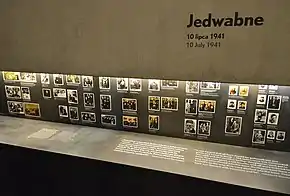

Sociologist Jan Gross writes that a leading role in the 1941 Jedwabne pogrom was carried out by four Polish men, including Jerzy Laudański and Karol Bardoń, who had earlier collaborated with the Soviet NKVD and were now trying to recast themselves as zealous collaborators with the Germans.[71]

Historian John Connelly wrote that the vast majority of ethnic Poles showed indifference to the fate of the Jews; and that "Polish historiography has hesitated to view [complicity in the Holocaust of Jews] as collaboration... [instead viewing it] as a form of society's 'demoralization'".[7] Klaus-Peter Friedrich wrote that "most [Poles] adopted a policy of wait-and-see... In the eyes of the Jewish population, [this] almost inevitably had to appear as silent approval of the [German] occupier's actions."[3] According to historian Gunnar S. Paulsson, in occupied Warsaw (a city of 1.3 million, including 350,000 Jews before the war), some 3,000 to 4,000 Poles acted as blackmailers and informants (szmalcowniks) who turned in Jews and fellow-Poles who provided assistance to Jews.[72] Grzegorz Berendt estimates the number of Polish citizens who participated in anti-Jewish actions as being a "group of dozens of thousands of individuals".[73]

In 2013, historian Jan Grabowski wrote in his book Hunt for the Jews that "one can assume that the number of victims of the Judenjagd could reach 200,000—and this in Poland alone."[74] The book was praised by some scholars for its approach and analysis,[75][76] while a number of other historians criticized his methodology for lacking in actual field research,[77] and argued that his "200,000" estimate was too high.[78][79]

The Lviv pogrom was carried out by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), Ukrainian People's Militia and local Ukrainian mobs in the city of Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine), between June and July 1941, shorty after the German takeover of the city.[80] The pogrom was organized by the German SS Einsatzgruppe C and OUN leaders under a pretext that the local Jews were co-responsible for the earlier Soviet atrocities in the city.[81] In total, around 6,000 Jews were killed by the Ukrainians, followed by an additional 3,000 executed in subsequent Einsatzgruppe killings. The pogrom culminated in the so-called "Petlura Days" massacre, when more than 2,000 Jews were killed.[82]

Collaboration by ethnic minorities

Germans used the divide and rule method to create tensions within the Polish society, by targeting several non-Polish ethnic groups for preferential treatment or the opposite, in the case of the Jewish minority.[83]

German minority

During the invasion of Poland in September 1939, members of the German ethnic minority in Poland, which had numbered some 750,000 persons before the war,[84] assisted Nazi Germany in its war effort. The number of Germans in prewar Poland who belonged to pro-Nazi German organizations is estimated at some 200,000, primarily members of Jungdeutsche Partei, Deutsche Vereinigung, Naziverein, and Deutsche Jugendschaft in Polen.[85] They committed sabotage, diverted regular forces, and committed numerous atrocities against the civilian population.[86][87] Additionally, German-minority activists helped draw up a list of 80,000 Poles who were to be arrested after the invasion of Poland by German forces; most of those on the list lost their lives in the first few months of the war.[88] Volksdeutsche were highly praised by German authorities for providing information on Poland and on Polish activists, which was considered invaluable to the successful military campaign against Poland.[89]

Shortly after the German invasion of Poland, an armed ethnic-German militia, the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz, was formed, numbering some 100,000 members.[90] It organized the Operation Tannenberg mass murder of Polish elites. At the beginning of 1940, the Selbstschutz was disbanded, and its members were transferred to various SS, Gestapo, and German-police units. The Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle organized large-scale looting of property, and redistributed goods to Volksdeutsche. They were given apartments, workshops, farms, furniture, and clothing confiscated from Jewish Poles and ethnic Poles.[91] In Gdańsk Pomerania, by 22 November 1939, 30% of the German population (38,279 persons) had joined the Selbstschutz (almost all the German men in the region) and had executed some 30,000 Poles.[92]

During the German occupation of Poland, Nazi authorities established a German People's List (Deutsche Volksliste", or "DVL), whereby former Polish citizens of German ethnicity were registered as Volksdeutsche. The German authorities encouraged registration of ethnic Germans, and in many cases made it mandatory. Those who joined were given benefits, including better food and better social status. However, Volksdeutsche were required to perform military service for the Third Reich, and hundreds of thousands joined the German military, either willingly or under compulsion.[93]

According to Ryszard Kaczmarek, in 1939 Poland's German minority numbered some 750,000 and constituted the principal citizen collaborators.[94][95]

Ukrainians and Belarusians

.jpg.webp)

Before the war, Poland had a substantial population of Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities living in her eastern, Kresy regions. After the Soviet invasion of eastern Poland on 17 September 1939, those territories were annexed by the USSR. Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, German authorities recruited Ukrainians and Belarusians who had been citizens of Poland before September 1939 for service in the Waffen-SS and auxiliary-police units, serving as guards in the German-run extermination camps set up by the Nazis in occupied-Poland, and to assist with anti-partisan operations.[96] In District Galicia, the SS Galicia division and Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, made up of ethnic-Ukrainian volunteers, took part in widespread massacres and persecution of Poles and Jews.[97][98] Also, as early as the September Campaign, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (Orhanizatsiya Ukrayins'kykh Natsionalistiv, or OUN) had been “a faithful German auxiliary"[99] carrying out acts of sabotage against Polish targets on behest of the Abwehr.[100]

Jewish collaborators

A minority of Jews chose to collaborate with the Germans. Jews helped the Germans in return for limited freedom, safety and other compensation (food, money) for the collaborators and their relatives. Some were motivated purely by self-interest, such as individual survival, revenge, or greed;[101] others were coerced into collaborating with the Germans.[49]:67

The Judenräte (s. Judenrat, literally "Jewish council") were Jewish-run governing bodies set up by the Nazi authorities in Jewish ghettos across German-occupied Poland. The Judenräte functioned as a self-enforcing intermediary and were used by the Germans to control the Jewish population and to manage the ghetto's day-to-day administration. The Germans also required Judenräte to confiscate property, organize forced labor, collect information on the Jewish population and facilitate deportations to extermination camps. [102][103] [104]:117–118 In some cases, Judenrat members exploited their positions to engage in bribery and other abuses. In the Łódź Ghetto, the reign of Judenrat head Chaim Rumkowski was particularly inhumane, as he was known to get rid of his political opponents by submitting their names for deportation to concentration camps, hoard food rations, and sexually abuse Jewish girls.[105][106][104] Tadeusz Piotrowski cited Jewish survivor Baruch Milch who wrote that "Judenrat became an instrument in the hand of the Gestapo for extermination of the Jews... I do not know of a single instance when the Judenrat would help some Jew in a disinterested manner." through Piotrowski cautions that "Milch's is a particular account of a particular place and time... the behavior of Junderat members was not uniform." [49]:73-74 Political theorist Hannah Arendt stated that without the assistance of the Judenräte, the German authorities would have encountered considerable difficulties in drawing up detailed lists of the Jewish population, thus allowing for at least some Jews to avoid deportation.[104]

The Jewish Ghetto Police (Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst) were volunteers recruited from among Jews living in the ghettos who could be relied on to follow German orders. They were issued batons, official armbands, caps, and badges, and were responsible for public order in the ghetto. Also, the policemen were used by the Germans for securing the deportation of other Jews to concentration camps.[107][108] The numbers of Jewish police varied greatly depending on the location, with the Warsaw Ghetto numbering about 2,500, Łódź Ghetto 1,200 and smaller ghettos such as that at Lwów about 500.[109]:310 Historian and Warsaw Ghetto archivist Emanuel Ringelblum described the cruelty of the Jewish Ghetto Police as "at times greater than that of the Germans", concluding that this formation's members distinguished themselves by their shocking corruption and immorality.[101][108]

In Warsaw, the collaborationist groups Żagiew and Group 13, led by Abraham Gancwajch and colloquially known as the "Jewish Gestapo", inflicted considerable damage on both Jewish and Polish underground resistance movements.[110] Over a thousand such Jewish Nazi collaborators, some armed with firearms,[49]:74 served under the German Gestapo as informers on Polish resistance efforts to hide Jews,[110] and engaged in racketeering, blackmail, and extortion in the Warsaw Ghetto.[111][112] A 70-strong group led by a Jewish collaborator called Hening was tasked with operating against the Polish resistance, and was quartered at the Gestapo's Warsaw headquarters on ulica Szucha (Szuch Street).[49]:74 Similar groups and individuals operated in towns and cities across German-occupied Poland — including Józef Diamand in Kraków[113] and Szama Grajer in Lublin.[114] It is estimated that at the end of 1941 and the start of 1942 there were some 15,000 "Jewish Gestapo" agents in the General Government.[49]:74

Jewish agent-provocateurs were used by the Germans to bait Jews hiding outside of the ghettos, turn them over to the Germans, and occasionally entrap Poles who were helping the Jews. Perhaps the largest of such actions involved agents from the Żagiew network, who falsely promised Jews hiding in Warsaw following its ghetto's liquidation and who held or were hoping to obtain foreign passports a safe place at Hotel Polski; Around 2,500 Jews came out of their hiding places and moved to the hotel, where they have been captured by the Germans.[49]:74 In another, smaller incident in the village of Paulinów, the Germans used a Jewish agent to pose as an escapee looking for a hiding place with a Polish family, after receiving help the agent denounced the Polish family to the Germans, resulting in the deaths of 12 Poles and several Jews who were hiding with the family.[115][116] Smaller scale provocations were more common, with Jewish agents approaching Polish resistance members asking for fake documents, followed by Gestapo arresting said resistance members.[117]

Some members of Jewish Social Self-Help (Jüdische Soziale Selbsthilfe), also known as the Jewish Social Assistance Society, collaborated with Nazi authorities in the deportation of Warsaw Jews to death camps. The group was formed as a humanitarian organization funded by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which also supplied it with legal cover,[118] and was allowed to operate within the General Government. Concerned with its lack of effectiveness, and seeing it as a cover for Nazi atrocities, both Jewish and Polish underground movements actively resisted the organization.[119]

Gorals and Kashubians

The Germans singled out as potential collaborators two ethnographic groups that had some separatist interests: the Kashubians in the north, and the Gorals in the south. They reached out to the Kashubians, but that plan proved a "complete failure".[83]:86-87 The Germans had some limited success with the Gorals – establishing the Goralenvolk movement, which Katarzyna Szurmiak calls "the most extensive case of collaboration in Poland during the Second World War."[83]:86-87 Overall, however, "when talking about numbers, the attempt to create [a] Goralenvolk was a failure... a mere 18 percent of the population took up Goralian IDs... Goralian schools [were] consistently boycotted, and... attempts to create a Goralian police or a Goralian Waffen-SS Legion... failed miserably."[83]:98

Notable collaborators

The Tom Organization

Tom's Organization was a group of spies formed in 1943 by collaborator Hubert Jura, known by the nickname of "Tom" as well as the alias Herbert Jung,[120] who was of mixed German and Polish ancestry. The group is theorized to have been formed by Jura and his friends after they were expelled from the Home Army due to criminal activity, using German support as a way to take revenge. They managed to insert themselves into the National Armed Forces, with Jura commanding a group of soldiers. In 1944, after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising, members of the Tom Organization came to Częstochowa. "Tom" received a villa from the Germans at Jasnogórska Street, which became the headquarter of the group for a few months. Later in 1944, a group of soldiers of the National Armed Forces commanded by Jura attacked the village of Petrykozy. According to the report from March 9, two Jews hiding there were murdered. After the war, most of the organization's members fled and Jura as well as his former associate, Gestapo member Paul Fuchs[121] operated for the US intelligence network created to work in the newly established countries controlled by the Soviet Union. Later, Jura moved to Venezuela, and in 1993 to Argentina.[121]

Kalkstein and Kaczorowska

In 1942, Ludwik Kalkstein started to collaborate together with Blanka Kaczorowska for the Gestapo. Kalkstein and Kaczorowska were responsible for the subsequent capture and execution of several high ranking Polish underground Home Army officers, including General Stefan Rowecki.[122] In 1944, Ludwik Kalkstein served in SS (during the Warsaw Uprising).[123] His wife was protected by the Gestapo until the end of the war.

See also

References

- Hobsbawm, Eric (1995) [1st pub. HMSO:1994]. "The Fall of Liberalism". Age of Extremes The Short Twentieth Century 1914-1991. Great Britain: Abacus. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-349-10671-7.

[T]he Poles, though strongly anti-Russian and anti-Jewish, did not significantly collaborate with Nazi Germany, whereas the Lithuanians and some of the Ukrainians (occupied by the USSR from 1939-41) did.

- Wojciechowski, Marian (2004). "Czy istniała kolaboracja z Rzeszą Niemiecką i ZSRR podczas drugiej wojny światowej?". Rocznik Towarzystwa Naukowego Warszawskiego (in Polish). 67: 17. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

kolaboracja... miała charakter-na terytoriach RP okupowanych przez Niemców-absolutnie marginalny

- Friedrich, Klaus-Peter (Winter 2005). "Collaboration in a 'Land without a Quisling': Patterns of Cooperation with the Nazi German Occupation Regime in Poland during World War II". Slavic Review. 64 (4): 711–746. doi:10.2307/3649910. JSTOR 3649910.

- Adam Galamaga (21 May 2011). Great Britain and the Holocaust: Poland's Role in Revealing the News. GRIN Verlag. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-640-92005-1. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- Hugo Service (11 July 2013). Germans to Poles: Communism, Nationalism and Ethnic Cleansing After the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-107-67148-5.

- Berghahn, Volker R. (1999). "Germans and Poles 1871–1945". In Bullivant, K.; Giles, G. J.; Pape, W. (eds.). Germany and Eastern Europe: Cultural Identities and Cultural Differences. Rodopi. p. 32. ISBN 978-9042006881.

- Connelly, John (2005). "Why the Poles Collaborated so Little: And Why That Is No Reason for Nationalist Hubris". Slavic Review. 64 (4): 771–781. doi:10.2307/3649912. JSTOR 3649912.

- Berendt, Grzegorz (2011), "The Price of life : the economic determinants of Jews' existence on the "Aryan" side", in Rejak, Sebastian; Frister, Elzbieta (eds.), Inferno of choices : Poles and the Holocaust., Warsaw: RYTM, pp. 115–165

- Joshua D. Zimmerman (5 June 2015). The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-107-01426-8.

- Czesław Madajczyk, Kann man in Polen 1939-1945 von Kollaborationsprechen, okupation und Kollaboration 1938-1945. Beitrage zu Konzepten und Praxis der Kollaboration in der deutschen Okkupationspolitik, Berlin, Heidelberg, W. Rohr, 1994,p. 140.

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1998). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947. McFarland. ISBN 9780786403714.

- News Flashes from Czechoslovakia Under Nazi Domination. The Council. 1940.

- Kochanski, Halik (2012). The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-674-06816-2.

- Piasecki, Waldemar (2017-07-31). Jan Karski. Jedno życie. Tom II. Inferno (in Polish). Insignis. ISBN 9788365743381.

- Blatman, Daniel (2002). "Were These Ordinary Poles?". Yad Vashem Studies. Jerusalem. XXX: 51–66.

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1999). A world at arms: a global history of World War II (1. paperback ed., reprinted ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55879-2.

- Cargas, Harry James (1994-06-28). Voices from the Holocaust. University Press of Kentucky. p. 84. ISBN 978-0813108254.

- "Wincenty Witos 1874–1945" (in Polish). Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- Roszkowski, Wojciech; Kofman, Jan (2016-07-08). Biographical Dictionary of Central and Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. ISBN 9781317475934.

- Bramstedt, E. K. (2013-09-27) [1945]. Dictatorship and Political Police: The Technique of Control by Fear. Routledge. p. 154. ISBN 9781136230592.

- School & Society. Science Press. 1940. p. 113.

- The Polish Review. Polish information center. 1943. p. 338.

- Czeslaw Madajczyk "Nie chciana kolaboracja. Polscy politycy i nazistowskie Niemcy w Lipcu 1940", Bernard Wiaderny, Paryz 2002, Dzieje Najnowsze 35/2 226-229 2003

- "Just before the outbreak of the Second World War, Hitler spoke of the planned mass murder of Poles and asked, 'Who, after all, is today speaking about the destruction of the Armenians?'... Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine would be populated by [German] pioneer farmer-soldier families." Alex Ross, "The Hitler Vortex: How American racism influenced Nazi thought", The New Yorker, 30 April 2018, pp. 71–72.

- Kunicki, Mikołaj (2001). "Unwanted Collaborators: Leon Kozłowski, Władysław Studnicki, and the Problem of Collaboration among Polish Conservative Politicians in World War II". European Review of History: Revue Européenne d'Histoire. 8 (2): 203–220. doi:10.1080/13507480120074260. ISSN 1469-8293. S2CID 144137847.

- Kunicki, Mikołaj Stanisław (2012-07-04). Between the Brown and the Red: Nationalism, Catholicism, and Communism in Twentieth-Century Poland—The Politics of Bolesław Piasecki. Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780821444207.

- Czesław Madajczyk, Polityka III Rzeszy w okupowanej Polsce, Warsaw, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1970, vol. 1, p. 242.

- Böhler, Jochen; Gerwarth, Robert (2016-12-01). The Waffen-SS: A European History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192507822.

- Hempel, Adam (1987). Policja granatowa w okupacyjnym systemie administracyjnym Generalnego Gubernatorstwa: 1939–1945 (in Polish). Warsaw: Instytut Wydawniczy Związków Zawodowych. p. 83.

- "Policja Polska w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie 1939-1945 – Policja Panstwowa". policjapanstwowa.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2018-03-29. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- "'Orgy of Murder': The Poles Who 'Hunted' Jews and Turned Them Over to the Nazis". Haaretz.

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz, 1940- (1998). Poland's holocaust : ethnic strife, collaboration with occupying forces and genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947. Mazal Holocaust Collection. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0786403713. OCLC 37195289.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lityński, Adam (2013-12-15). "Marek Mączyński, Organizacyjno-prawne aspekty funkcjonowania administracji bezpieczeństwa i porządku publicznego dla zajętych obszarów polskich w latach 1939-1945, ze szczgólnym uwzględnieniem Krakowa jako stolicy Generalnego Gubernatorstwa, 2012". Czasopismo Prawno-Historyczne. 65 (2): 471–479. doi:10.14746/cph.2013.65.2.29. ISSN 0070-2471.

- Andrzej Solak (17–24 May 2005). "Zbrodnia w Malinie – prawda i mity (1)". Nr 29-30. Myśl Polska: Kresy. Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on October 5, 2006. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

Reprint: Zbrodnia w Malinie (cz.1) Głos Kresowian, nr 20.

- Józef Turowski, Pożoga: Walki 27 Wołyńskiej Dywizji AK, PWN, ISBN 83-01-08465-0, pp. 154-155.

- Cezary Chlebowski, Reportaż z tamtych dni Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, Warszawa 1988, ss. 248-249

- Tomkiewicz, Monika. (2008). Zbrodnia w Ponarach 1941-1944. Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej--Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu. ISBN 9788360464915. OCLC 318200999.

- Jacek Andrzej Młynarczyk (2009). "Pomiędzy współpracą a zdradą. Problem kolaboracji w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie – próba syntezy". Pamięć I Sprawiedliwość: Biuletyn Głównej Komisji Badania Zbrodni Przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej. 1 (14): 113.

- Kaczmarek, Ryszard (2010), Polacy w Wehrmachcie [Poles in the Wehrmacht] (in Polish), Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, first paragraph, ISBN 978-83-08-04494-0, archived from the original on November 15, 2012, retrieved June 28, 2014,

Paweł Dybicz for Tygodnik "Przegląd" 38/2012.

- German Army Service (Volume 423 ed.). Hansard. 4 June 1946. p. cc307–8W. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- Antoni Mączak, Encyklopedia historii gospodarczej Polski do 1945 roku: O-Ż (Encyclopedia of Poland's Economic History: O–Ż), Warsaw, Wiedza Powszechna, 1981.

- "BAUDIENST Służba Budowlana w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie 1940-1945" (PDF) (in Polish). Fundacjia „Polsko-Niemieckie Pojednanie”, Muzeum Historii Polskiego Ruchu Ludowego, Zakład Historii Ruchu Ludowego.

- Haltof, Marek (2012). Polish Film and the Holocaust: Politics and Memory. Berghahn Books. p. 11. ISBN 9780857453570.

Poland had no feature film production during the occupation.

- NISIOBĘCKA, ANETA. "ARTYŚCI W CZASIE OKUPACJI" [Artists under the [German] Occupation] (PDF) (in Polish). Institute of National Remembrance. p. 66.

Some actors were coerced by the Germans into collaborating. The Germans wanted to create the appearance that "order" prevailed in Poland, and that people who did not rebel were provided with entertainment at a level suitable for them. Bogusław Samborski played in the anti-Polish film Heimkehr probably in order to save his Jewish wife. (pl.: Niektórych aktorów Niemcy szantażem zmuszali do współpracy. Zależało im na stworzeniu pozorów, że w Polsce panuje „ład i porządek”, a ludzie, którzy się nie buntują, mają zapewnioną rozrywkę na odpowiednim dla nich poziomie. Bogusław Samborski zagrał w antypolskim filmie Heimkehr, prawdopodobnie po to, by ratować żonę-Żydówkę.

- Haltof, Marek (2002). Polish National Cinema. Berghahn Books. p. 44. ISBN 9781571812759.

Tylko świnie siedzą w kinie

- Bogusław Kunach (2003-12-01). "Być tym, co słynie. Igo Sym" (in Polish). Gazeta Wyborcza. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- Guzik, Mateusz (2015-08-20). "Adolf Dymsza: Złamana kariera słynnego polskiego komika". Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- Davies, Norman (2008-09-04). Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw. Pan Macmillan. p. 287. ISBN 9780330475747.

They are particularly incensed by the false accusation that the Home Army did not accept Jews, and by even wilder talk about it being an anti-Semitic organization. The fact is, Jews with the various religious or political connections served with distinction both in the Home Army and in the People's Army.

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1998). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947. McFarland. ISBN 9780786403714.

- Edward Kossoy Zydzi w Powstaniu Warszawskim

- Powstanie warszawskie w walce i dyplomacji - page 23 Janusz Kazimierz Zawodny, Andrzej Krzysztof Kunert - 2005 Był również czterdziestoosobowy pluton żydowski, dowodzony przez Samuela Kenigsweina, który walczył w batalionie AK „Wigry"

- Review by John Radzilowski of Yaffa Eliach's There Once Was a World: A 900-Year Chronicle of the Shtetl of Eishyshok, in Journal of Genocide Research, vol. 1, no. 2 (June 1999), City University of New York.

- Bubnys, Arūnas (1998). Vokiečių okupuota Lietuva (1941-1944). Vilnius: Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras. ISBN 978-9986-757-12-2.

- (in Lithuanian) Rimantas Zizas. Armijos Krajovos veikla Lietuvoje 1942–1944 metais (Activities of Armia Krajowa in Lithuania in 1942–1944). Armija Krajova Lietuvoje, pp. 14–39. A. Bubnys, K. Garšva, E. Gečiauskas, J. Lebionka, J. Saudargienė, R. Zizas (editors). Vilnius – Kaunas, 1995.

- Garlinski, Josef (1985-08-12). Poland in the Second World War. Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-09910-8.

- Zimmerman, Joshua D. (2015). The Polish underground and the Jews, 1939-1945. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01426-8.

- Biskupski, Mieczysław (2000). The history of Poland. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. pp. 110. ISBN 978-0313305719. OCLC 42021562.

- Cymet, David (June 1999). "Polish state antisemitism as a major factor leading to the Holocaust". Journal of Genocide Research. 1 (2): 169–212. doi:10.1080/14623529908413950. ISSN 1469-9494.

- Cooper, Leo (2000). In the shadow of the Polish eagle: the Poles, the Holocaust, and beyond. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York, N.Y.: Palgrave. ISBN 978-1-280-24918-1. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- Poles and Jews: perceptions and misperceptions. Polin. Władysław Bartoszewski (ed.) (1. issued in paperback ed.). Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. 2004. p. 356. ISBN 978-1-904113-19-5.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Schatz, Jaff (1991). The generation : the rise and fall of the Jewish communists of Poland. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0520071360. OCLC 22984393.

- Mushkat, Marion (1992). Philo-Semitic and anti-Jewish attitudes in post-Holocaust Poland. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0773491762. OCLC 26855644.

- Instytut Pamięci Narodowej--Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu. Biuro Edukacji Publicznej (2007). Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej. Instytut. p. 73.

- Wozniak, Albion (2003). The Polish Studies Newsletter. Albin Wozniak.

- Żebrowski, Leszek (1994). Brygada Świętokrzyska NSZ (in Polish). Gazeta Handlowa.

- Korbonski, Stefan (1981). The polish underground state: a guide to the underground 1939 - 1945. New York: Hippocrene Books. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-88254-517-2.

- Biddiscombe, Perry (2013). The SS hunter battalions : the hidden history of the Nazi Resistance Movement 1944-45. New York: The History Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780752496450. OCLC 852756721.

- Komunistyczny donos do gestapo

- Bułhak, Władisław. "Donos wywiadu Gwardii Ludowej do gestapo na rzekomych komunistów i kryptokomunistów (wrzesień 1943 roku)" (PDF) (in Polish).

- Winstone, Martin (2014). The Dark Heart of Hitler's Europe: Nazi rule in Poland under the General Government. London: Tauris. pp. 181–186. ISBN 978-1-78076-477-1.

- Gross (2001), Neighbors, p. 75.

- "Warsaw". www.ushmm.org. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- "Prof. Berendt w Wiedniu: Zadaniem pokazanie różnicy w polskim i żydowskim doświadczeniu lat 1939-45". dzieje.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2019-02-09.

- Grabowski, Jan (2013). Hunt for the Jews: betrayal and murder in German-occupied Poland. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01074-2.

- "Hunt for the Jews snags Yad Vashem book prize", Times of Israel (JTA), 8 December 2014.

- "Professor Jan Grabowski wins the 2014 Yad Vashem International Book Prize", Yad Vashem, 4 December 2014.

- Samsonowska, Krystyna (July 2011). "Dąbrowa Tarnowska - nieco inaczej. (Dąbrowa Tarnowska - not quite like that)". Więź. 7: 75–85.

- Grzegorz Berendt (24 February 2017). ""The Polish People Weren't Tacit Collaborators with Nazi Extermination of Jews" (opinion)". Haaretz.

- Musial, Bogdan (2011). "Judenjagd – 'umiejętne działanie' czy zbrodnicza perfidia?"". Dzieje Najnowsze: kwartalnik poświęcony historii XX wieku (in Polish). Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

- Himka, John-Paul (2011). "The Lviv Pogrom of 1941: The Germans, Ukrainian Nationalists, and the Carnival Crowd". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 53 (2–4): 209–243. ISSN 0008-5006. Taylor & Francis.

- Ronald Headland (1992). Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941-1943. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 0838634184.

- Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- Wendt, Anton Weiss (11 August 2010). Eradicating Differences: The Treatment of Minorities in Nazi-Dominated Europe. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-2449-1.

- Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939: Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce Intelligenzaktion (It Was 1939: Intelligenzaktion [Operation Intelligentsia] of the German Security Police in Poland), Warsaw, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej (Institute of National Remembrance), 2009, ISBN 978-83-7629-063-8, p. 20.

- Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939 Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, IPN Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2009 ISBN 978-83-7629-063-8 p. 23.

- Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939 Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, IPN Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2009 ISBN 978-83-7629-063-8.

- Christopher R. Browning, Jürgen Matthäus, The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942: A Comprehensive History of the Holocaust, Lincoln, Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-1327-2, 2004, p. 33.

- Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939 Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, IPN Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2009 ISBN 978-83-7629-063-8 p. 49.

- Maria Wardzyńska, Był rok 1939 Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion, IPN Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2009 ISBN 978-83-7629-063-8 p. 49.

- Michael Geyer, Sheila Fitzpatrick, Beyond Totalitarianism: Stalinism and Nazism Compared, Cambridge University Press, 2009, p. 155.

- August Frank, "Memorandum, September 26, 1942: Utilization of property on the occasion of settlement and evacuation of Jews", in NO-724, Pros. Ex. 472, United States of America v. Oswald Pohl, et al. (Case no. 4, the "Pohl Trial"), V, pp. 965–67.

- "22 listopada 1939 r. do Selbstschutzu w Okręgu Rzeszy Gdańsk-Prusy Zachodnie należało 38 279 osób. Stanowiło to ponad 30 proc. mniejszości niemieckiej na Pomorzu Gdańskim. Do Samoobrony wstąpili prawie wszyscy mężczyźni [...] Jesienią 1939 r. członkowie Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz dokonali mordów polskiej ludności cywilnej w conajmniej 359 miejscowościach. Szacuje się, że egzekucje pochłonęły życie 30 tys. osób w Okręgu Rzeszy Gdańsk-Prusy Zachodnie." Tomasz Ceran, Zapomniani kaci Hitlera: Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz w okupowanej Polsce 1939-1940: wybrane zagadnienia (Hitler's Forgotten Executioners: the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz in Occupied Poland, 1939–1940: selections), pp. 302-3. Ziemie polskie pod okupacją 1939-1945. Centralny Projekt Badawczy IPN. Warsaw, 2016.

- Historia: Encyklopedia Szkolna, Warsaw, Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 1993, pp. 357–58.

- Ryszard Kaczmarek (2008). "Kolaboracja na terenach wcielonych do Rzeszy Niemieckiej" (PDF). Pamięć I Sprawiedliwość (7/1 (12)): 166.

Na wschodzie, na polskich terenach wcielonych, przed wybuchem wojny olbrzymią rolę odgrywała mniejszość niemiecka i spośród jej przedstawicieli rekrutowała się głównie grupa aktywnych kolaboracjonistów.

- Chu, Winson (2012-06-25). The German Minority in Interwar Poland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107008304.

- "Ukrainians guards took part in extermination". The Jerusalem Post. Associated Press. 2010-01-10. Retrieved 2019-06-21.

- Czesław Partacz, Krzysztof Łada, Polska wobec ukraińskich dążeń niepodległościowych w czasie II wojny światowej, (Toruń: Centrum Edukacji Europejskiej, 2003)

- Timothy Snyder. (2004) The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press: pp. 165–166

- John A. Armstrong, Collaborationism in World War II: The Integral Nationalist Variant in Eastern Europe, The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Sep., 1968), p. 409.

- Recenzje i polemiki: W. Szpicer, W. Moroz – Krajowyj Prowindyk Wołodymyr Tymczij – „Łopatynśkij”, Wydawnictwo Afisza, Lwów, 2004. W: Grzegorz Motyka: Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość. Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej nr 2/10/2006. Warszawa: IPN, 2006, s. 357-361. ISSN 1427-7476.

- Ringelblum, Emmanuel (2015-11-06). Notes From The Warsaw Ghetto: The Journal Of Emmanuel Ringelblum. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 9781786257161.

- Hilberg 1995, p. 106.

- Bauman, Robert J. (2012-04-19). Extension of Life. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781469192451.

- Hannah Arendt (2006). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. The Wannsee Conference, or Pontius Pilate. Penguin. ISBN 978-1101007167. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- Rees, Laurence,Auschwitz: The Nazis and the "Final Solution", especially the testimony of Lucille Eichengreen, pp. 105-131. BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-52296-6.

- Rees, Laurence."Auschwitz: Inside the Nazi state". BBC/KCET, 2005. Retrieved: 01.10.2011.

- "Judischer Ordnungsdienst". Museum of Tolerance. Simon Wiesenthal Center. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- Collins, Jeanna R. "Am I a Murderer?: Testament of a Jewish Ghetto Policeman (review)". Mandel Fellowship Book Reviews. Kellogg Community College. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- Hilberg, Raul (2003). The destruction of the European Jews. Yale University Press. OCLC 49805909.

- Piecuch, Henryk (1999). Syndrom tajnych służb: czas prania mózgów i łamania kości. Agencja Wydawnicza CB. ISBN 978-83-86245-66-6.

- Israel Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, 1939–1943: Ghetto, Underground, Revolt, Indiana University Press, 1982, ISBN 0-253-20511-5, pp. 90–94.

- Itamar Levin, Walls Around: The Plunder of Warsaw Jewry during World War II and Its Aftermath, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, ISBN 0-275-97649-1, pp. 94–98.

- Dąbrowa-Kostka, Stanisław (1972). W okupowanym Krakowie: 6.IX.1939 - 18.I.1945 (in Polish). Wydaw. Min. Obrony Nar.

- Radzik, Tadeusz (2007). Extermination of the Lublin ghetto (in Polish). Wydawn. Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej. ISBN 9788322726471.

- Teresa Prekerowa, Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Sciences, "Who Helped Jews during the Holocaust in Poland", Acta Poloniae Historica, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Semper, vol. 76, p. 166. ISSN 0001-6829 "The gravest provocation involving Jews took place in 1943, some 100 km east of Warsaw; a Jewish Gestapo agent posing as a fugitive was given, or promised, help by 14 inhabitants of the village of Paulinów." Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1997

- Joanna Kierylak, Treblinka Museum, "12 sprawiedliwych z Paulinowa", 2013, retrieved 2018-05-25. "Akcja niemiecka, zakrojona na szeroką skalę... Posłużono się tu prowokacją. Rozpoznania dokonali prowokatorzy. Byli nimi Żydzi, jeden z Warszawy, drugi ze Sterdyni – Szymel Helman. Prowokator z Warszawy dołączył do ukrywających się Żydów, podając się za Żyda francuskiego, zbiegłego z transportu przesiedleńców wiezionych do Treblinki." ("[In a] large-scale German operation... use was made of provocation. The scouting-out was done by agent-provocateurs. They were Jews, here one from Warsaw, the other from Sterdyń—Szymel Helman. The agent-provocateur from Warsaw joined some Jews who were in hiding, giving himself out to be a French Jew who had escaped from a transport of deportees who were being sent to Treblinka.")

- Witold W. Mędykowski (2006). "Przeciw swoim: Wzorce kolaboracji żydowskiej w Krakowie i okolicy". Zagłada Żydów - Studia I Materiały, Rocznik Naukowy Centrum Badań Nad Zagładą Żydów (in Polish) (2): 206.

- Alexandra Garbarini, Jewish Responses to Persecution: 1938–1940, p. 198.

- Szapiro, Paweł. "Żydowski Urząd Samopomocy (ŻUS)". Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (in Polish). Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- Ślaski, Jerzy (1999). Polska walcząca [Poland Fighting] (in Polish). Rytm. p. 1037. ISBN 9788387893316.

Hubert Jura aka Herbert Jung ... acting as Captain Tom, in fact, a Gestapo agent (pl - Hubert Jura vel Herbert Jung...wystepujacy jako kapitan Tom w rzeczywistości agent gestapo.)

- Sobkowski, Jarosław. "Członek Brygady Świętokrzyskiej założył w Częstochowie katownię. Za wiedzą Niemców". czestochowa.wyborcza.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- Grabowski, Waldemar (2004). "Kalkstein i Kaczorowska w świetle akt UB". Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej (8–09): 87-100.

- "Kalkstein. Podwójny agent całe życie ucieka". wyborcza.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2019-09-10.