Colonial Parkway

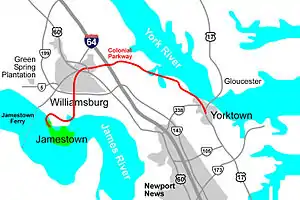

Colonial Parkway is a 23-mile (37 km) scenic parkway linking the three points of Virginia's Historic Triangle, Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Yorktown. It is part of the National Park Service's Colonial National Historical Park. Virginia's official state classification for the parkway is State Route 90003.[1] With portions built between 1930 and 1957, it links the three communities via a roadway shielded from views of commercial development. The roadway is toll-free, is free of semi trucks, and has speed limits of around 35 to 45 mph (55 to 70 km/h). As a National Scenic Byway and All-American Road (one of only 31 in the U.S.), it is also popular with tourists due to the James River and York River ends of the parkway. A video drive-thru is available.

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Route information | |

| Maintained by National Park Service | |

| Length | 23 mi (37 km) |

| Tourist routes | |

| Major junctions | |

| West end | Jamestown, Virginia |

| East end | |

| Highway system | |

|

| |

Bridges and interchanges

For most roads it crosses it does not have an intersection with that road. It normally goes on a bridge, under a bridge, or in a tunnel (the only tunnel is the tunnel under Colonial Williamsburg). Examples of this happening: when it crosses Interstate 64 and US Route 60. When it crosses a road (if it even has an intersection with it) it is more like an interchange than a crossroad. Almost every overpass is made of brick and made to look like it was made in the Colonial era (most roads that go over the Colonial Parkway instead of the bridges that the Colonial Parkway uses to travel over other roads, like Interstate 64). It resembles a Colonial trail or wagon road in the Colonial era with most of the wildlife and animals at the York River and the James River (at the ends or near the ends). The Parkway is a connector of Virginia's Historic Triangle and other roads or the Jamestown Ferry (to State Route 10).

Route description

_in_James_City_County%252C_Virginia.jpg.webp)

Since the Parkway is intended primarily for sightseeing, and only secondarily as a through route to the historic points, there are many scenic pull-offs with historical markers giving brief descriptions of the view. The more popular pull-offs are near the James River and York River ends of the parkway, where there are panoramic views across each river. The Colonial Parkway is mostly covered by trees and is very shady in the summer and spring or beautiful in the fall and winter. The western end of the parkway begins at Jamestown, on Jamestown Island (see image), where the Virginia Colony was begun in 1607 on the shore of the James River. Some visitors begin their experience by approaching the entire area from the south via State Route 10 to Surry, and then across the James River and arriving by water on the Jamestown Ferry. The middle point of the Parkway is at Williamsburg, where the capital of Virginia Colony was moved in 1699, from Jamestown. The parkway tunnels under the historic district of Colonial Williamsburg. The eastern end of the Parkway is at Yorktown, where General Cornwallis surrendered to George Washington in 1781 towards the completion of the American Revolution.

_at_the_junction_with_the_Colonial_Parkway_in_Williamsburg%252C_Virginia.jpg.webp)

The Colonial Parkway is free of trucks and commercial vehicles except passenger-carrying buses. The lower speed limits, enforced by the National Park Service law enforcement rangers, coupled with few exits, combine to help preserve the road for tourists and protect wildlife by making it an unattractive short-cut for most local traffic and commuters. It has no painted traffic lane-marking lines, and some stretches are posted "Pass With Care". The unmarked pavement is made of rounded "river gravel" set in a concrete-mix, providing an unusual earth tone color. Despite a federal policy instituted late in the 20th century of requiring user fees at many National Parks and Monuments, the Colonial Parkway has remained toll-free.

History

.jpg.webp)

The Colonial Parkway took over 25 years to create from concept to completion.

Design and planning

In 1930, a survey of the area was undertaken by National Park Service (NPS) engineering and landscape architect professionals for a 500-foot (150 m) right-of-way for the parkway. Between Yorktown and Williamsburg, the initial proposals called for the parkway to follow an inland route along colonial-era roads. However, instead, it was decided to align the road along the York River through U.S. Navy land to avoid grade crossings, extensive tangents, modern intrusions and other "visual junk". This land included the Naval Weapons Station (Yorktown) and the former E.I. DuPont explosives factory and town complex at Penniman, Virginia which later became known as Cheatham Annex.

Following the parkway concept of Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted, designers of New York City's Central Park, the planners of the Colonial Parkway used a model of a limited access highway with broad sweeping curves, set in a landscaped right-of-way devoid of commercial development. These features, derived from 19th-century Romantic landscape theories, created a safer and more pleasant drive compared to the increasingly congested urban strips. In addition to protecting the views, culvert headwalls and parkway underpasses were clad in "Virginia-style" brick laid in English and Flemish bonds to promote a "colonial-era" effect. Design features such as molded coping rails, string courses and buttresses followed the historical prototypes found at Williamsburg.[2]

Construction

The land for ten miles (16 km) of the route between Yorktown and Williamsburg was given to the NPS free of charge, and construction began on first on this portion. By 1937, the road was completed to just outside Williamsburg. There was some debate over the routing in the Williamsburg area, and eventually a tunnel was selected. The tunnel under the historic district of Colonial Williamsburg was completed by 1942, but opening was delayed by World War II and some structural and flooding problems. It finally opened for traffic in 1949, leaving only the Williamsburg-to-Jamestown section to be built.

The parkway was closed through Navy lands near Yorktown during World War II. New utility lines and access roads were built across the parkway to serve defense needs and the road was used for convoy training. In 1945, the U.S. Navy agreed to halt all transports on the parkway and help in the restoration of the landscape destroyed during three years of wartime use.

During the early 1950s in anticipation of the 1957 350th anniversary of Jamestown's founding, the park finalized plans to complete the parkway, still following the same design standards. Several long fills were required near the James River and workers rebuilt the isthmus to Jamestown Island which had been severed by weather since the colonial days when Jamestown was actually a peninsula. Other major improvements at the southern terminus included development of Jamestown Island as part of the Colonial National Historical Park and the adjacent Jamestown Festival Park, which was largely state-funded by Virginia. On April 27, 1957, the Colonial Parkway was opened for traffic along the entire route between Yorktown and Jamestown.

After completion

The Colonial Parkway has been carefully maintained. Traffic safety for the wildlife and tourists on the low speed Parkway is provided by United States Park Police. The average speed limit along the parkway is 45 miles per hour, though there are places with 35 mph speed zones. Canada geese as pedestrians have the right-of-way on the Colonial Parkway. Priority is given wetlands ecosystems and the natural growth as well as wildlife and waterfowl preservation. The scenic shoreline areas along the two major tidal rivers present extra challenges with many bridges and fills. Occasionally, East Coast hurricanes such as Hurricane Isabel in 2003 inflict significant natural damage, and require closure of portions of the Parkway for repairs.

It has also been necessary to protect the Parkway from commercial intrusions, especially as the Virginia Peninsula's resident population has more than tripled since 1930, and tourism has greatly increased. Improvements such as the overpass crossings of Interstate 64 and upgrades of State Route 199, and U.S. Route 17 at Yorktown, all major traffic arteries, were accomplished in a manner so as to be virtually unnoticeable to travelers along the Parkway. Even the CSX Transportation railroad line which crosses with Amtrak service to Williamsburg and Newport News is shielded from view.

Major intersections

| County | Location | mi | km | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| York | Yorktown | 0 | 0.0 | Ballard Street (SR 1020) - Battlefield Visitor Center, Main Street, Waterfront, Coast Guard Training Center | |

| | 1 | 1.6 | interchange | ||

| | 3 | 4.8 | American Revolution Museum at Yorktown (SR 1020) | interchange | |

| | 4 | 6.4 | interchange | ||

| | 6 | 9.7 | Queens Lake (SR 716) | interchange | |

| City of Williamsburg | 9 | 14 | Parkway Drive | interchange; former SR 163 | |

| 11 | 18 | ||||

| 13 | 21 | Williamsburg (North England Street) | |||

| Tunnel under Colonial Williamsburg | |||||

| 15 | 24 | Newport Avenue - Williamsburg | interchange | ||

| James City | | 18 | 29 | interchange | |

| Jamestown | 21 | 34 | Jamestown Settlement (SR 359) | ||

| 23 | 37 | Historic Jamestowne | |||

| 1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi | |||||

See also

- State Route 5, a Virginia Byway linking the area with Richmond and the James River Plantations on the north shore of the river.

- State Route 10, linking the Richmond Metro area and Suffolk on the south shore of the river, providing access to James River Plantations on the south side, Hopewell, City Point, and Smithfield.

- Hampton Roads, about the region.

- Colonial Parkway Killer, about the murders that occurred on or near the Colonial Parkway during the 1980s.

References

- Traffic Engineering Division (2009). 2009 Virginia Department of Transportation Daily Traffic Volume Estimates Including Vehicle Classification Estimates (Where Available). Jurisdiction Report US (Federal) (PDF) (Report). Virginia Department of Transportation. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- McClelland, Linda Flint (1998). Building the National Parks: Historic Landscape Design and Construction, p. 224. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5583-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Colonial Parkway. |

- NPS.gov: Official Colonial National Historical Park website — plan your visit on-line.

- NPS.gov: Colonial Parkway webpage

- VDOT Jamestown Ferry website

- Virginia Roads - Colonial Parkway (Steve Alpert)

- HAER No. VA-48, "Colonial Parkway, Yorktown to Jamestown Island, Yorktown, York County, VA", 75 photos, 5 color transparencies, 9 measured drawings, 102 data pages, 7 photo caption pages

- HAER No. VA-48-A, "Colonial Parkway, Navy Mine Depot", 3 photos, 8 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. VA-48-B, "Colonial Parkway, Capitol Landing Underpass", 5 photos, 10 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. VA-48-C, "Colonial Parkway, C&O Railroad Underpass", 6 photos, 2 measured drawings, 10 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. VA-48-D, "Colonial Parkway, Williamsburg Tunnel", 2 photos, 2 measured drawings, 12 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. VA-48-E, "Colonial Parkway, Ballard Creek Culvert", 1 photo, 8 data pages

- HAER No. VA-48-F, "Colonial Parkway, Bracken Pond Culvert", 1 photo, 8 data pages

- HAER No. VA-48-G, "Colonial Parkway, Jones Mill Pond Dam", 2 photos, 11 data pages

- HAER No. VA-48-H, "Colonial Parkway, Indian Field Creek Bridge", 1 photo, 9 data pages

- HAER No. VA-48-I, "Colonial Parkway, Felgates Creek Bridge", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-J, "Colonial Parkway, Kings Creek Bridge", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-K, "Colonial Parkway, Halfway Creek Bridge", 1 photo, 8 data pages

- HAER No. VA-48-L, "Colonial Parkway, Virginia Route 143 Bridge", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-M, "Colonial Parkway, College Creek Bridge", 1 photo, 1 color transparency

- HAER No. VA-48-N, "Colonial Parkway, Mill Creek Bridge", 2 photos, 10 data pages

- HAER No. VA-48-O, "Colonial Parkway, Powhatan Creek Bridge", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-P, "Colonial Parkway, Isthmus Bridge", 1 photo, 9 data pages

- HAER No. VA-48-Q, "Colonial Parkway, Yorktown Creek Bridge", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-R, "Colonial Parkway, U.S. Route 17 Bridge", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-S, "Colonial Parkway, Virginia Route 238 Bridge", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-T, "Colonial Parkway, Glebe Cut Culvert", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-U, "Colonial Parkway, Newport Avenue Bridge", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-V, "Colonial Parkway, North Pier Bridge", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-W, "Colonial Parkway, Virginia Route 641 Bridge", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-X, "Colonial Parkway, Hubbards Lane Bridge", 1 photo

- HAER No. VA-48-Y, "Colonial Parkway, Interstate 64 Bridge", 1 photo, 1 color transparency

- HAER No. VA-48-Z, "Colonial Parkway, Route 199 Bridge", 1 photo, 12 data pages

- HAER No. VA-48-AA, "Colonial Parkway, Parkway Drive Bridge", 1 photo, 8 data pages

- Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) No. VA-74, "Colonial Parkway", 8 data pages