Comparison (grammar)

Comparison is a feature in the morphology or syntax of some languages whereby adjectives and adverbs are inflected to indicate the relative degree of the property they define exhibited by the word or phrase they modify or describe. In languages that have it, the comparative construction expresses quality, quantity, or degree relative to some other comparator(s). The superlative construction expresses the greatest quality, quantity, or degree—i.e. relative to all other comparators.

| Grammatical features |

|---|

| Related to nouns |

| Related to verbs |

| General features |

| Syntax relationships |

|

| Semantics |

| Phenomena |

The associated grammatical category is degree of comparison.[1] The usual degrees of comparison are the positive, which simply denotes a property (as with the English words big and fully); the comparative, which indicates greater degree (as bigger and more fully); and the superlative, which indicates greatest degree (as biggest and most fully).[2] Some languages have forms indicating a very large degree of a particular quality (called elative in Semitic linguistics). Other languages (e.g. English) can express lesser degree, e.g. beautiful, less beautiful, least beautiful.

The comparative degrees are frequently associated with adjectives and adverbs because these words take the -er suffix or modifying word more or less. (e.g., faster, more intelligent, less wasteful). Comparison can also, however, appear when no adjective or adverb is present, for instance with nouns (e.g., more men than women). However, the usage of the word than between nouns simply denotes a comparison made and not degree of comparison comparing the intensity or the extent of the subjects. One preposition, near, also has comparative and superlative forms, as in Find the restaurant nearest your house.

Formation of comparatives and superlatives

Comparatives and superlatives may be formed in morphology by inflection, as with the English and German -er and -(e)st forms and Latin's -ior (superior, excelsior), or syntactically, as with the English more... and most... and the French plus... and le plus... forms. Common adjectives and adverbs often produce irregular forms, such as better and best (from good) and less and least (from little/few) in English, and meilleur (from bon) and mieux (from the adverb bien) in French.

Comparative and superlative constructions

Most if not all languages have some means of forming the comparative, although these means can vary significantly from one language to the next.

Comparatives are often used with a conjunction or other grammatical means to indicate to what the comparison is being made, as with than in English, als in German, etc. In Russian and Greek (Ancient, Koine and Modern), this can be done by placing the compared noun in the genitive case. With superlatives, the population being considered may be explicitly indicated, as in "the best swimmer out of all the girls".

Languages also possess other structures for comparing adjectives and adverbs; English examples include "as... as" and "less/least...".

А few languages apply comparison to nouns and even verbs. One such language is Bulgarian, where expressions like "по̀ човек (po chovek), най човек (nay chovek), по-малко човек (po malko chovek)" (literally more person, most person, less person but normally better kind of a person, best kind of person, not that good kind of a person) and "по̀ обичам (po obicham), най-малко обичам (nay malko obicham)" (I like more, I like the least) are quite usual.[note 1]

Usage when considering only two things

In many languages, including English, traditional grammar requires the comparative form to be used when exactly two things are being considered, even in constructions where the superlative would be used when considering a larger number. For instance, "May the better man win" would be considered correct if there are only two individuals competing. However, this rule is not always observed in informal usage; the form "May the best man win" will often be used in that situation, as is required if there were three or more competitors involved.[3] However, in some cases when two subjects with equal qualities are compared, usage of superlative degree isn't possible. For example, "Ram is as good as Shyam"—positive degree; "Ram is not better than Shyam"—comparative degree. Since Ram and Shyam are equally good, neither is superior which negates the usage of the superlative.

Rhetorical use of unbalanced comparatives

In some contexts such as advertising or political speeches, absolute and relative comparatives are intentionally employed in ways that invite comparison, yet the basis of comparison is not explicit. This is a common rhetorical device used to create an implication of significance where one may not actually be present. Although common, such usage is sometimes considered ungrammatical.[3]

For example:

- Why pay more?

- We work harder.

- We sell for less!

- More doctors recommend it.

Usage in languages

English

English has two grammatical constructions for expressing comparison: a morphological one formed using the suffixes -er (the "comparative") and -est (the "superlative"), with some irregular forms, and a syntactic one using the adverbs "more", "most", "less" and "least".

As a general rule, words of one syllable require the suffix (except for the four words fun, real, right, wrong), while words of three or more syllables require "more" or "most". This leaves words of two syllables—these are idiomatic, some requiring the morphological construction, some requiring the syntactic and some able to use either (e.g., polite can use politer or more polite), with different frequencies according to context.[4]

Morphological comparison

The suffixes -er (the "comparative") and -est (the "superlative") are of Germanic origin and are cognate with the Latin suffixes -ior and -issimus and Ancient Greek -īōn and -istos. They are typically added to shorter words, words of Anglo-Saxon origin, and borrowed words fully assimilated into English vocabulary. Usually the words taking these inflections have fewer than three syllables.

This system also contains a number of irregular forms, some of which, like "good", "better", and "best", contain suppletive forms. These irregular forms include:

| Positive | Comparative | Superlative |

|---|---|---|

| good | better | best |

| well | ||

| bad, evil | worse | worst |

| ill | ||

| far | farther | farthest |

| further | furthest | |

| little | less(er) | least |

| many | more | most |

| much |

Syntactic comparison

In syntactic construction, inserting the words "more" or "most"[note 2] before an adjective or adverb modifies the resulting phrase to express a relative (specifically, greater) degree of that property. Similarly, inserting the diminutives "less" or "least" before an adjective or adverb expresses a lesser degree.

This system is most commonly used with words of French or Latin derivation; with adjectives and adverbs formed with suffixes other than -ly (e.g., "beautiful"); and with longer, technical, or infrequent words. For example:

| Positive | Comparative | Superlative |

|---|---|---|

| beautiful | more beautiful | most beautiful |

| often | more often | most often |

| observant | less observant | least observant |

| coherently | less coherently | least coherently |

Absolute adjectives

Some adjectives' (the absolute adjectives) meanings are not exhibitable in degrees, making comparative constructions of them inappropriate. Some qualities are either present or absent such as being cretaceous vs. igneous, so it appears illogical to call anything "very cretaceous", or to characterize something as "more igneous" than something else.

Some grammarians object to the use of the superlative or comparative with words such as full, complete, unique, or empty, which by definition already denote a totality, an absence, or an absolute.[5] However, such words are routinely and frequently qualified in contemporary speech and writing. This type of usage conveys more of a figurative than a literal meaning, because in a strictly literal sense, something cannot be more or less unique or empty to a greater or lesser degree.

Many prescriptive grammars and style guides include adjectives for inherently superlative qualities to be non-gradable. Thus, they reject expressions such as more perfect, most unique, and most parallel as illogical pleonasms: after all, if something is unique, it is one of a kind, so nothing can be "very unique", or "more unique" than something else.

Other style guides argue that terms like perfect and parallel never apply exactly to things in real life, so they are commonly used to mean nearly perfect, nearly parallel, and so on; in this sense, more perfect (i.e., more nearly perfect, closer to perfect) and more parallel (i.e., more nearly parallel, closer to parallel) are meaningful.

Balto-Slavic languages

In most Balto-Slavic languages (such as Czech, Polish, Lithuanian and Latvian), the comparative and superlative forms are also declinable adjectives.

In Bulgarian, comparative and superlative forms are formed with the clitics по- (more) and най- (most):

- голям (big)

- по-голям (bigger)

- най-голям (biggest)

In Czech, Polish, Slovak, Ukrainian, Serbo-Croatian and Slovene, the comparative is formed from the base form of an adjective with a suffix and superlative is formed with a circumfix (equivalent to adding a prefix to the comparative).

- mladý / młody / mladý / молодий / mlad / mlad (young)

- mladší / młodszy / mladší / молодший / mlađi / mlajši (younger)

- nejmladší / najmłodszy / najmladší / наймолодший / najmlađi / najmlajši (youngest)

In Russian, comparative and superlative forms are formed with a suffix or with the words более (more) and самый (most):

- добрый (kind)

- добрее/более добрый (kinder)

- добрейший/самый добрый (kindest)

Romance languages

In contrast to English, the relative and the superlative are joined into the same degree (the superlative), which can be of two kinds: comparative (e.g. "the most beautiful") and absolute (e.g. "very beautiful").

French: The superlative is created from the comparative by inserting the definitive article (la, le, or les), or the possessive article (mon, ton, son, etc.), before "plus" or "moins" and the adjective determining the noun. For instance: Elle est la plus belle femme → (she is the most beautiful woman); Cette ville est la moins chère de France → (this town is the least expensive in France); C'est sa plus belle robe → (It is her most beautiful dress). It can also be created with the suffix "-issime" but only with certain words, for example: "C'est un homme richissime" → (That is the most rich man). Its use is often rare and ironic.

Spanish: The comparative superlative, like in French, has the definite article (such as "las" or "el"), or the possessive article ("tus," "nuestra," "su," etc.), followed by the comparative ("más" or "menos"), so that "el meñique es el dedo más pequeño" or "el meñique es el más pequeño de los dedos" is "the pinky is the smallest finger." Irregular comparatives are "mejor" for "bueno" and "peor" for "malo," which can be used as comparative superlatives also by adding the definite article or possessive article, so that "nuestro peor error fue casarnos" is "our worst mistake was to get married."

The absolute superlative is normally formed by modifying the adjective by adding -ísimo, -ísima, -ísimos or -ísimas, depending on the gender or number. Thus, "¡Los chihuahuas son perros pequeñísimos!" is "Chihuahuas are such tiny dogs!" Some irregular superlatives are "máximo" for "grande," "pésimo" for "malo," "ínfimo" for "bajo," "óptimo" for "bueno," "acérrimo" for "acre," "paupérrimo" for "pobre," "celebérrimo" for "célebre."

There is a difference between comparative superlative and absolute superlative: Ella es la más bella → (she is the most beautiful); Ella es bellísima → (she is extremely beautiful).

Portuguese and Italian distinguish comparative superlative (superlativo relativo) and absolute superlative (superlativo absoluto/assoluto). For the comparative superlative they use the words "mais" and "più" between the article and the adjective, like "most" in English. For the absolute superlative they either use "muito"/"molto" and the adjective or modify the adjective by taking away the final vowel and adding issimo (singular masculine), issima (singular feminine), íssimos/issimi (plural masculine), or íssimas/issime (plural feminine). For example:

- Aquele avião é velocíssimo/Quell'aeroplano è velocissimo → That airplane is very fast

There are some irregular forms for some words ending in "-re" and "-le" (deriving from Latin words ending in "-er" and "-ilis") that have a superlative form similar to the Latin one. In the first case words lose the ending "-re" and they gain the endings errimo (singular masculine), errima (singular feminine), érrimos/errimi (plural masculine), or érrimas/errime (plural feminine); in the second case words lose the "-l"/"-le" ending and gain ílimo/illimo (singular masculine), ílima/illima (singular feminine), ílimos/illimi (plural masculine), or ílimas/illime (plural feminine), the irregular form for words ending in "-l"/"-le" is somehow rare and, in Italian but nor is Portuguese, it exists only in the archaic or literary language. For example:

- "Acre" (acer in Latin) which means acrid, becomes "acérrimo"/"acerrimo" ("acerrimus" in Latin). "Magro" ("thin" in Portuguese) becomes "magérrimo."

- Italian simile (similis in Latin) which means "similar," becomes (in ancient Italian) "simillimo" ("simillimus" in Latin).

- Portuguese difícil ("hard/difficult") and fácil (facile).

Romanian, similar to Portuguese and Italian, distinguishes comparative and absolute superlatives. The comparative uses the word "mai" before the adjective, which operates like "more" or "-er" in English. For example: luminos → bright, mai luminos → brighter. To weaken the adjective, the word "puțin" (little) is added between "mai" and the adjective, for example mai puțin luminos → less bright. For absolute superlatives, the gender-dependent determinant "cel" precedes "mai," inflected as "cel" for masculine and neuter singular, "cei" for masculine plural, "cea" for feminine singular, and "cele" for feminine and neuter plural. For example: cea mai luminoasă stea → the brightest star; cele mai frumoase fete → the most beautiful girls; cel mai mic morcov → the smallest carrot.

Indo-Aryan languages

Hindi-Urdu (Hindustani)ː When comparing two quantities makes use of the instrumental case-marker se (से سے) and the noun or pronoun takes the oblique case. Words like aur (और اور) "more, even more", zyādā (ज़्यादा زیادہ) "more" and kam (कम کم) "less" are added for relative comparisons. When equivalence is to be shown, the personal pronouns take the oblique case and add the genitive case-marker kā (का کا) while the nouns just take in the oblique case form and optionally add the genitive case-marker. The word zyādā (ज़्यादा زیادہ) "more" is optional, while kam (कम کم) "less" is required, so that in the absence of either "more" will be inferred.[6]

| Hindi-Urdu | Word order | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| vo usse lambī hai | [that].NOM [that].INST [tall].FEM [is] | She is taller than him/her. |

| vo usse zyādā lambī hai | [that].NOM [that].INST [more] [tall].FEM [is] | She is more tall them him/her. |

| vo usse aur lambī hai | She is even taller then him/her. | |

| vo uske jitnī lambī hai | [that].NOM [that].GEN [that much].REL [tall].FEM [is] | She is as tall as him/her. |

| vo us bacce jitnī lambī hai | [that].NOM [that].OBL [kid].OBL.MASC [that much].REL [tall].FEM [is] | She is as tall as the kid. |

| vo usse kam lambī hai | [that].NOM [that].INST [less] [tall].FEM [is] | She is shorter than him/her. |

| kamrā kalse (zyādā) sāf hai | [room].NOM.MASC [yesterday].INST [more] [clean] [is] | The room is cleaner compared to yesterday. |

Superlatives are made through comparisons with sab ("all") with the instrumental postposition se as the suffix. Comparisons using "least" are rare; it is more common to use an antonym.[7]

| Hindi-Urdu | Word order | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| sabse sāf kamrā | [all].INST [clean] [room].NOM.MASC | The cleanest room. |

| sabse kam sāf kamrā | [all].INST [less] [clean] [room].NOM.MASC | The least clean room |

| sabse gandā kamrā | [all].INST [dirty].NOM.MASC [room].NOM.MASC | The dirtiest room. |

| kamrā sabse (zyādā) sāf hai | [room].NOM.MASC [all].INST [clean] [is] | The room is the cleanest |

| kamrā sabse kam sāf hai | [room].NOM.MASC [all].INST [less] [clean] [is] | The room is the least clean |

| kamrā sabse gandā hai | [room].NOM.MASC [all].INST [dirty].MASC [is] | The room is the dirtiest |

In Sanskritised and Persianised registers of Hindustani, comparative and superlative adjectival forms using suffixes derived from those languages can be found.[8]

| English | Sanskrit | Persian | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative | -er | -tar | |

| adhiktar

(more) |

bêhtar

(better) | ||

| Superlative | -est | -tam | -tarīn |

| adhiktam

(most) |

bêhtarīn

(best) | ||

Celtic languages

Scottish Gaelic: When comparing one entity to another in the present or the future tense, the adjective is changed by adding an e to the end and i before the final consonant(s) if the final vowel is broad. Then, the adjective is preceded by "nas" to say "more," and as to say "most." (The word na is used to mean than.) Adjectives that begin with f are lenited. and as use different syntax constructions. For example: Tha mi nas àirde na mo pheathraichean. → I am taller than my sisters. Is mi as àirde. → I am the tallest.

As in English, some forms are irregular, i.e. nas fheàrr (better), nas miosa (worse), etc.

In other tenses, nas is replaced by na bu and as by a bu, both of which lenite the adjective if possible. If the adjective begins with a vowel or an f followed by a vowel, the word bu is reduced to b'. For example:

- Bha mi na b' àirde na mo pheathraichean. → I was taller than my sisters.

- B' e mi a b' àirde. → I was the tallest.

Welsh is similar to English in many respects. The ending -af is added onto regular adjectives in a similar manner to the English -est, and with (most) long words mwyaf precedes it, as in the English most. Also, many of the most common adjectives are irregular. Unlike English, however, when comparing just two things, the superlative must be used, e.g. of two people - John ydy'r talaf (John is the tallest).

In Welsh, the equative is denoted by inflection in more formal registers, with -ed being affixed to the adjective, usually preceded, but not obligatorily, by cyn (meaning 'as'). For example: Mae Siôn cyn daled â fi (Siôn is as tall as me). Irregular adjectives have specific equative forms, such as da (‘good’): cystal = 'as good as'.

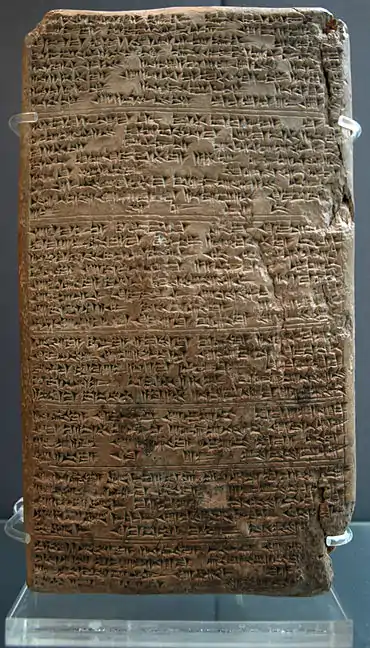

Akkadian

(The first sign "e" is rubbed off; only a space-(depression) locates it.)-(high resolution expandible photo)

In Akkadian cuneiform, (on a 12 paragraph clay tablet), from the time period of the 1350 BC Amarna letters (a roughly 20-year body of letters), two striking examples of the superlative extend the common grammatical use. The first is the numeral "10," as well as "7 and 7." The second is a verb-spacement adjustment.

The term "7 and 7" means 'over and over'. The phrase itself is a superlative, but an addition to some of the Amarna letters adds "more" at the end of the phrase (EA 283, Oh to see the King-(pharaoh)): "... I fall at the feet of the king, my lord. I fall at the feet of the king, my lord, 7 and 7 times more, ....".[9]:323–324 The word 'more' is Akkadian mila, and by Moran is 'more' or 'overflowing'. The meaning in its letter context is "...over and over again, overflowing," (as 'gushingly', or 'obsequiously', as an underling of the king).

The numeral 10 is used for ten times greater in EA 19, Love and Gold, one of King Tushratta's eleven letters to the Pharaoh-(Amenhotep IV-Akhenaton). The following quote using 10, also closes out the small paragraph by the second example of the superlative, where the verb that ends the last sentence is spread across the letter in s-p-a-c-i-n-g, to accentuate the last sentence, and the verb itself (i.e. the relational kingly topic of the paragraph):

- ".... Now, in keeping with our constant and mutual love, you have made it 10 times greater than the love shown my father. May the gods grant it, and may Teššup, my lord, and Aman make flourish for evermore, just as it is now, this mutual love of ours.[9]:42–46

The actual last paragraph line contains three words: 'may it be', 'flourish', and 'us'. The verb flourish (from napāhu?, to light up, to rise), uses: -e-le-né-ep-pi-, and the spaces. The other two words on the line, are made from two characters, and then one: "...may it be, flourish-our (relations)."

Estonian

In Estonian, the superlative form can usually be formed in two ways. One is a periphrastic construction with kõige followed by the comparative form. This form exists for all adjectives. For example: the comparative form of sinine 'blue' is sinisem and therefore the periphrastic superlative form is kõige sinisem. There is also a synthetic ("short") superlative form, which is formed by adding -m to the end of the plural partitive case. For sinine the plural partitive form is siniseid and so siniseim is the short superlative. The short superlative does not exist for all adjectives and, in contrast to the kõige-form, has a lot of exceptions.

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- Comparatives in Bulgarian are formed with the particles по and най, separated from the following adjective or adverb by a hyphen. If they are applied to a noun or a verb, they are written as separate words with a grave accent over по po. Comparatives in Macedonian are formed identically but written as one word.

- "More" and "most" are themselves the irregular comparatives of "many" and "much".

References

- Huddleston, Rodney; Pullum, Geoffrey (2002), The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, pp. 1099–1170

- Tom McArthur, ed. (1992) The Oxford Companion to the English Language, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-214183-X

- Trenga, Bonnie (12 August 2008). "Comparatives Versus Superlatives". Grammar Girl. Quick and Dirty Tips.

- Kytö, Merja; Romaine, Suzanne (21 June 2013). "Competing forms of adjective comparison in modern English: What could be more quicker and easier and more effective?".

- Quirk, Randolph; Greenbaum, Sidney; Leech, Geoffrey; Svartvik, Jan (1985), A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language, Longman, pp. 404, 593

- Trends in Hindi Linguisticsː Differential comparatives in Hindi-Urdu (September 2018) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327595669_Differential_comparatives_in_Hindi-Urdu

- Shapiro (2003:265)

- Shapiro (2003:265)

- Moran, William L. (1992) [1987], The Amarna Letters (2nd ed.), Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-80186-715-0