County of Drenthe

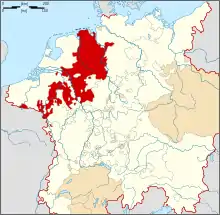

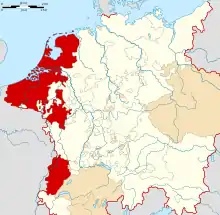

The County of Drenthe (Dutch: Landschap Drenthe, German: Grafschaft Drente), was a province of the Holy Roman Empire from 1046, and of the Dutch Republic from 1581 until 1795. It corresponds to the area west of the lower Ems, today the eponymous province of Drenthe in the Netherlands.

Drenthe is first recorded in 820 as a Gau, the basic division of the Carolingian Empire east of the Rhine.[1] In 1046, the Emperor Henry III granted it to the Bishopric of Utrecht. At the time Drenthe included the city of Groningen, which was governed by a burgrave (prefect) enfeoffed by the bishop. By the 14th century, the prefecture was hereditary and the Lordship of Groningen was de facto separate from the County of Drenthe.[2]

Between 1225 and 1240, the free peasants of Drenthe were in conflict with the bishops over his lordship and his tithes. This even resulted in a crusade launched against them. The first and most intense phase of the conflict is retold in an eyewitness account, Quaedam narracio.[3] In the 14th and 15th centuries, Drenthe was affected by the factional struggle between the Vetkopers and Schieringers. In 1402, it was attached to the Oversticht, the eastern portion of the bishopric.[2]

In 1412, the county received its own Landrecht (territorial law). In 1522, during the Guelders Wars, the county fell to Charles II, Duke of Guelders, but he was forced to cede it to the Habsburg emperor Charles V in the Treaty of Grave of 1536.[1] It was thereafter governed by a Habsburg stadtholder, but because it was only sparsely populated, it had the same stadtholder as the Lordship of Groningen. In the Treaty of Augsburg of 1548, Drenthe was removed from the Westphalian Circle and attached to the Burgundian Circle, making it one of the Seventeen Provinces of the Habsburg Netherlands with a special status within the Empire.[4]

During the Dutch Revolt against the Habsburgs, Drenthe joined the Union of Utrecht. Although it became part of the republic, it was not one of the Seven Provinces and did not have a seat in the States General on account of its poverty.[1]

References

Footnotes

- Köbler 2007, p. 252.

- Henstra 2000, pp. 212–213.

- Van Bavel 2010.

- Wilson 2016, p. 228.

Bibliography

- Henstra, D. J. (2000). The Evolution of the Money Standard in Medieval Frisia: A Treatise on the History of the Systems of Money of Account in the Former Frisia. Uitgeverij Verloren.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoppenbrouwers, P. (2018). Village Community and Conflict in Late Medieval Drenthe. The Medieval Countryside. 20. Turnhout: Brepols. doi:10.1484/M.TMC-EB.5.112979. ISBN 978-2-503-57539-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Köbler, G. (2007). Historisches Lexikon der Deutschen Länder: die deutschen Territorien vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. Munich: C. H. Beck.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Bavel, B. J. P. (2010). "Rural Revolts and Structural Change in the Low Countries, Thirteenth – Early Fourteenth Centuries". In Richard Goddard; John Langdon; Miriam Müller (eds.). Survival and Discord in Medieval Society: Essays in Honour of Christopher Dyer. Brepols. pp. 249–268.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, P. H. (2016). Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674058095.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)